Abstract

This one-arm pre-post repeated measures study had two objectives: 1) evaluate the safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization for Groups (ASSYST-G) in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression symptoms, and 2) to assess the effectiveness of the ASSYST-G in the PTSD or CPTSD diagnosis status remission in the refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced population in transit through Mexico to the USA border. A total of 54 (53 females and one male) persons met the inclusion criteria and participated in a three-day intensive treatment program. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 53 years old (M = 32.13 years).

Six applications of the ASSYST-G were provided to groups from Central and South America, and Africa, focusing on the worst experience of their lives (from the migration journey or any other part of their life, including childhood). PTSD or CPTSD diagnosis status was determined through the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ). PTSD symptoms monitoring was measured with the PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5), and anxiety and depression symptoms were measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). All psychometric evaluations were applied at three assessment time points: T1. Pre-treatment, T2. Post-treatment (7 days after the sixth administration of the intervention), and T3. Follow-up (14 days after the sixth administration of the intervention).

Results indicate a significant reduction in ITQ classification of CPTSD and PTSD from baseline to follow-up, with sustained improvement at T3. A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant differences across the three time points for all variables: PCL-5, F (2, 102) = 58.67, p < .001, η² = 0.53; Anxiety, F (2, 102) = 29.84, p < .001, η² = 0.37; Depression, F (2, 102) = 21.45, p < .001, η² = 0.30. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using paired t-tests indicated significant reductions in scores from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3 for all variables. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) showed the largest effect between T1 and T2 for PCL-5: d = 2.58; large effects were observed for Anxiety: d = 1.71; Depression: d = 1.37) at this point, suggesting the effectiveness of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention. Regarding safety, no adverse effects or events were reported by the participants during the administration of the treatment procedure or at follow-up. None of the participants showed clinically significant worsening/exacerbation of symptoms after treatment.

Keywords:Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization (ASSYST); Refugees; Asylum-Seekers; Forcibly Displaced People; Adaptive Information Processing (AIP); Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy; EMDR therapy protocols; EMDR group therapy protocols; posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); Complex PTSD (CPTSD); Stepped-care approach

Abbreviations: ASSYST: Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment; ASSYST-G: Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment for Groups; ASSYST-I: Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment for Individuals; EMDR therapy: Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy; EMDR-IGTP-OTS: EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress; EMDR-PRECI: EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents and Ongoing Traumatic Stress; PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; CPTSD: Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision; ITQ: International Trauma Questionnaire; IRB: Institutional Review Board; CONSORT: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; SPIRIT: Standard Protocol Items: Recommendation for Interventional Trials; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; DSO: Disturbances in Self-Organization; CAPS-5: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; NCPTSD: National Center for PTSD; TF-CBT: Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; AIP: Adaptive Information Processing; Low and Middle Income Countries: LMICs; High Income Countries: HICs; Potentially Traumatic Events: PTEs

Introduction

War, persecution, genocide, human rights violations, geopolitical conflicts, and climate change have forced individuals and families to flee their country of origin to seek international protection in other countries. As of May 2024, over 100 million people were registered as forcibly displaced, including 42.7 million refugees (formally defined as people who have a “fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, or membership of a particular social group or political opinion that is outside the country of his/her nationality”) and 8.4 million asylum-seekers (defined as people who have applied for international protection, and are waiting for a decision) [1]. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and comorbid disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and psychiatric disorders, has been found to be significantly higher among refugees, asylumseekers, and forcibly displaced persons than in host populations [2-5]. This is attributed to this population’s experience of, by definition, exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs), usually consisting of multiple and prolonged traumatic events and/or adverse experiences pre-migration, during the migration journey, and compounded by external stressors in host countries related to cultural, linguistic, and legal barriers [6].

PTSD is a mental health disorder and a pervasive global health issue, characterized by exposure to a Criterion A traumatic event(s), with a subsequent development or exacerbation of intrusion symptoms (nightmares and flashbacks), avoidance symptoms, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and arousal symptoms, resulting in deterioration in daily functioning and deleteriously impacting various aspects of life, including personal and professional relationships, physical health, and have devastating and long lasting impacts on individuals and consequently, on society as a whole [7-8]. PTSD symptom severity in refugee adults has also been evidenced to contribute to attachment difficulties and adversely affect parenting and subsequently the mental health of refugee youth [9].

Recently, attention has been drawn to the prevalence of complex PTSD (CPTSD) in adult refugees, asylum-seekers, and forcibly displaced populations and the need for evidence-based treatments specific to CPTSD with this population [10,11]. CPTSD is a variant of PTSD introduced in the eleventh revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) that includes disturbances in self-organization (DSO) symptoms, which present as affect dysregulation, difficulties in forming and maintaining personal relationships, and negative self-concept in addition to the PTSD diagnostic criteria [12]. CPTSD is thought to occur after exposure to severe and prolonged traumatic events, which in refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced population can include, but is not limited to, war, human rights violations, extreme and multiple interpersonal trauma, trafficking, exploitation, sexual violence, physical assault, kidnapping, witnessing murder, forced labor and prostitution, state and non-state torture, and prolonged childhood or domestic abuse during pre-migration and throughout sustained displacement [10,11].

Quantity and severity of exposure to PTEs and ongoing traumatic stress situations are shown to increase the risk of more severe PTSD symptomology in refugees, including the development of CPTSD [13]. Treatment of CPTSD and PTSD do not need to vary greatly. While a phased approach has historically been in favor for the treatment of individuals with CPTSD, evidence has shown that immediate trauma-focused treatment is effective and safe for individuals with PTSD or CPTSD [14]. It suggests that traumatic memories that cause intrusion symptoms should be targeted first [15,16]. Trauma-focused treatment interventions should be appropriate and effective in treating symptoms caused by memories associated with traumatic events or adverse experiences from distinct migration phases: pre-migration, migration (displacement), and post-migration (resettlement).

Trauma-focused psychotherapy, such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy (TF-CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy are considered the frontline treatments for PTSD in adult refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced populations [17]. However, most of the studies have been conducted in High Income Countries (HICs) and fewer have been conducted in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) where most refugees, asylum-seekers, and forcibly displaced people experience sustained displacement or are resettled [9]. It is recommended that mental health providers (MHPs) who treat refugees, asylum-seekers, and forcibly displaced people screen for PTSD as well as CPTSD and “to adapt existing trauma-focused treatments to address the additionally impairing DSO symptom clusters” (p.3) and that treatment of PTSD and CPTSD within the refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced people population should take into consideration the length of treatment and flexibility of treatment [10] due to low access to prolonged treatment options, high barriers, and potential poor treatment response.

One of the barriers is to treatment is that LMICs generally do not have the mental health infrastructure or mental health specialists who specialize in screening for these disorders and treatment with these approaches, which are typically not considered brief (six or fewer sessions), and is not conducive to access of treatment for this population [9]. Poor or non-treatment response in adult refugee populations has been hypothesized to be due to greater exposure to severe and prolonged traumatic events and adverse experiences and have higher levels of somatization and comorbidities than nonrefugee populations [18]. These factors have been found to hinder treatment response, along with the fact that treatment sometimes must occur in the presence of extreme stressors or ongoing traumatic stress situations, during migration and even post-migration, where most populations receive PTSD treatment in a relative context of safety [9].

Providing the most appropriate and effective treatment interventions for PTSD and CPTSD within this population is crucial not only for individual and familial health, but for community and societal benefits, as effective PTSD and CPTSD treatment can reduce pharmacological interventions and hospitalization. Research shows that without treatment interventions, PTSD symptom severity can persist for years after resettlement in host countries or in temporary placements, like refugee camps [13]. Two potential solutions to addressing treatment barriers for refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced populations are group treatment interventions and a stepped-care approach. Benefits of the provision of group mental health interventions to adult refugees were highlighted by 10 studies in a systematic review [19] while other studies recommended a steppedcare approach in the provision of specialized PTSD treatment interventions for this population [9,13,19].

Mexico has become a transit country for irregular migration, with the Mexico-US border considered the most dangerous land migration route due to the highest numbers of deaths, as migration routes through Mexico and sustained displacement in Mexico are characterized by exposure to PTEs and ongoing traumatic stress situations such as including, but not limited to, extreme weather conditions, kidnappings, exploitation, extortion, torture, physical and/or sexual violence, and witnessing murder [20]. Most refugees, asylum-seekers, and forcibly displaced people consider Mexico a transit country, and not a final migratory destination [21]. However, most are forced to remain in Mexico in sustained displacement for uncertain periods due to political, judicial, and economic barriers, further exposing them to PTEs and prolonged traumatic stress situations [22]. This study hopes to contribute to the growing body of literature on evidence-based trauma-focused brief treatment interventions in LMICs, effective and appropriate for the treatment of PTSD and CPTSD in adult refugees, asylumseekers, and forcibly displaced populations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial of its type.

AIP-Theoretical Model

The Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) model posits that memory networks of stored experiences are the basis of both mental health and pathology across the clinical spectrum [22]. When memories are adequately processed and adaptively stored, they form adaptive memory networks, which are the foundation for learning and future perceptions, behaviors, and responses [22]. When memories are inadequately processed and maladaptively stored due to heightened autonomic nervous system arousal states produced by adverse life experiences, pathogenic memory networks are formed, resulting in present-day suffering, difficulty, and symptoms (e.g., PTSD, anxiety, depression) [22].

These pathogenic memory networks are targeted and reprocessed through the facilitation of the information processing systems’ adaptive and natural processing of the information of the experience and the subsequent integration and storage of the information of the experience in adaptive memory networks linked by similar memory components, resulting in learning and mental health [22]. The AIP-theoretical model is the foundational model of the EMDR Standard Protocol, EMDR therapy protocols, and the ASSYST treatment interventions, which guides case conceptualization, clinical practice, and predicts clinical outcomes.

Previous ASSYST Treatment Intervention Studies

There have been 11 previous studies on the ASSYST treatment interventions with the following populations: 1) General population in lockdown and with ongoing traumatic stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2) TeleMental Health counseling to the general population after adverse experiences, 3) Mental Health Professionals working during the COVID-19 Pandemic with patients suffering from trauma-related disorders and stressors, 4) General population with non-recent pathogenic memories, 5) Adult Syrian refugees living in Lebanon, 6)Adult Females with Adverse Childhood Experiences, 7) Public sector workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic, 8) Female children polytraumatized by adverse childhood experiences, neglect, and maltreatment, 9) Adult females with breast and cervical cancer-related PTSD symptoms, 10) Adult individuals with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and 11) Survivors of a flood in Bulgaria [23-33].

The ASSYST Treatment Interventions

The Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization (ASSYST) treatment interventions were born during humanitarian fieldwork and are AIP-informed, evidence-based, carefully field-tested, and userfriendly psychophysiological algorithmic approaches, whose references are the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-IGTP-OTS) [34-39] and the EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents and Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-PRECI) [40-46]. The EMDR-IGTPOTS and the EMDR-PRECI are multi-component EMDR therapy protocols. The ASSYST-G is derived from the EMDR-IGTP-OTS, and the ASSYST-I is derived from the EMDR-PRECI. The ASSYST treatment interventions have the core components (the most therapeutically active) of these EMDR therapy protocols, requiring less time than the EMDR Standard Protocol or EMDR therapy protocols, making them less expensive, less complex, effective, efficient, and safe, enhancing the feasibility of delivering brief treatment in primary care settings worldwide.

These treatment interventions are specifically designed to provide in-person or online support to clients who present acute stress disorder (ASD) or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), intense psychological distress, and/or physiological reactivity caused by the disorders’ intrusion symptoms associated with the memories of the adverse experience(s).

The objective of these treatment interventions is focused on the patient’s Autonomic Nervous System sympathetic branch hyper-activation regulation through the reduction or removal of the activation produced by the sensory, emotional, or physiological components of the pathogenic memories of the adverse experience(s) to achieve optimal levels of Autonomic Nervous System activation, stop the major stress hormones secretion, and reestablish the Prefrontal Cortex functions (e.g., processing of information); thus, facilitating the AIP-system and the subsequent adaptive processing of information [47].

The ASSYST treatment interventions can be used during Critical Care (within the first few hours after a traumatic event or adverse experience), Rapid Response (within the first few days safter a traumatic event or adverse experience), Early Psychological and/or Psychosocial Intervention (within the first three months after a traumatic event or adverse experience), or beyond the three-month Early Intervention time frame during ongoing traumatic stress situations with no post-trauma safety period, or pathogenic memories temporally located in the past producing intrusion symptoms [48,49]. The ASSYST treatment interventions, in a group or individual format, are designed for the regulation of the autonomic nervous system and the processing of specific pathogenic memory components associated with the adverse experience(s).

Objectives

This one-arm pre-post repeated measures study had two objectives. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization for Groups (ASSYST-G) treatment intervention in reducing PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms in the adult refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced persons population in transit through Mexico to the US border. The secondary objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention in the remission of PTSD or CPTSD diagnosis status in the adult refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced persons population in transit through Mexico to the US border.

verse experience(s).

Method

Study Design

To measure the effectiveness of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention on the dependent variables PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms, this study, with an intention-to-treat analysis, used a one-arm, pre-post repeated measures design. PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms were measured at three time points for all participants in the study: Time 1. Pre-treatment assessment; Time 2. Post-treatment assessment (7 days after the sixth administration of the intervention), and Time 3. Followup assessment (14 days after the sixth administration of the intervention).

PTSD symptom monitoring was measured using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Participants who demonstrated PCL-5 scores > 30 during Time 2. Post-treatment assessment was to receive up to three sessions of maximum 60 minute “booster sessions” of the ASSYST-I treatment intervention in an intensive format, meaning three consecutive sessions in one or two days. None of the participants included in the study demonstrated PCL-5 scores of > 30 at Time 2. Post-treatment assessment, therefore, ASSYST-I treatment intervention “booster sessions” were not administered. To establish the PTSD or Complex PTSD (CPTSD) diagnosis status based on the International Classification of Diseases 11 (ICD-11), the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) was used at two time points for all participants: Time 1. Pre-treatment assessment and Time 3. Follow-up assessment.

Ethics and Research Quality

The research design protocol was reviewed and approved by the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board (also known in the United States of America as an Institutional Review Board) in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization – Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines, the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice of the European Medicines Agency (version 1 December 2016), and the Declaration of Helsinki (64th WMA General Assembly, October 2013). The research quality of this study was based on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010.

Participants

This study was conducted at the CAFEMIN migrant and refugee shelter in Mexico City, Mexico, from June 2024 to March 2025, with the adult refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced persons population in transit through Mexico to the US border with pathogenic memories associated with adverse experiences from pre-migration (including childhood), migration, or recent or present ongoing traumatic stress situations. 54 participants (53 females and one male) fulfilled the Inclusion criteria: (a) being an adult refugee, asylum-seeker, or forcibly displaced person staying at the CAFEMIN shelter, (b) having pathogenic memories of adverse experiences from pre-migration, the migration journey, or recent or present ongoing traumatic stress situations, (c) voluntarily participating in the study, (d) not receiving specialized trauma therapy, (e) not receiving drug therapy for PTSD symptoms, (f) having a PCL-5 total score of 30 points or more, (g) meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD or CPTSD, (h) plans to stay in the CAFEMIN shelter for at least 21 days.

Exclusion criteria were: (a) ongoing self-harm/suicidal or homicidal ideation, (b) diagnosis of schizophrenia, psychotic, or bipolar disorder, (c) diagnosis of a dissociative disorder, (d) organic mental disorder, (e) a current, active chemical dependency problem, (f) significant cognitive impairment (e.g., severe intellectual disability, dementia), (g) presence of uncontrolled symptoms due to a medical illness. Those who did not meet inclusion criteria (i.e., subclinical diagnostic criteria, staying in the shelter for less than 21 days) received the intervention for ethical and humanitarian reasons, but were not included in the study. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 53 (M =32.13 years). Participants’ nationalities were Venezuelan, Colombian, Ecuadorian, Guatemalan, Honduran, Salvadoran, and Equatorial Guinean. Participation was voluntary, with the participants signed informed consent in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Safety and symptoms worsening

We determined the safety of this three-day intensive traumafocused treatment intervention by recording the number of adverse effects (e.g., symptoms of dissociation, fear, panic, freeze, shut down, collapse, fainting), events (e.g., suicide ideation, suicide attempts, self-harm, homicidal ideation) or clinically significant worsening/exacerbation of symptoms on the PCL-5 reported by the participants during treatment or at follow-up. A symptom exacerbation was defined as a PCL-5 increase of > 8.8 points [50].

Instruments for Psychometric Evaluation

• To measure PTSD symptom severity and treatment response, we used the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) provided by the National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD), with the time interval for symptoms to be the past week. This weekly-administered version of the PCL-5 is largely comparable to the original monthly version [39]. The instrument was translated and back-translated into Spanish. It contains 20 items. Respondents indicated how much they have been bothered by each PTSD symptom over the past week using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0=not at all, 1=a little bit, 2=moderately, 3=quite a bit, and 4=extremely. A total symptom score of zero to 80 can be obtained by summing the items. The sum of the scores yields a continuous measure of PTSD symptom severity for symptom clusters and the whole disorder. Psychometrics for the PCL-5 validated against the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale-5 (CAPS- 5) diagnosis, suggest that a score of 31-33 is optimal to determine a probable PTSD diagnosis [51,52].

• To measure anxiety and depression symptoms severity and treatment response we used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) which has been used to evaluate these psychiatric comorbidities in various clinical settings at all levels of healthcare services and with the general population. The instrument was translated and back translated to Spanish. It is a 14-item self-report scale to measure the Anxiety (7 items) and Depression (7 items) of patients with both somatic and mental problems using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The response descriptors of all items are Yes, definitely (score 3); Yes, sometimes (score 2); No, not much (score 1); No, not at all (score 0). A higher score represents higher levels of Anxiety and Depression: a domain score of 11 or greater indicates Anxiety or Depression; 8–10 indicates borderline case; 7 or lower indicates no signs of Anxiety or Depression [53,54].

• To establish the PTSD or CPTSD diagnoses status based on the ICD-11, we used the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ). The ITQ consists of six items measuring the three PTSD clusters (re-experiencing; avoidance; and a sense of current threat) and six items that measure the three symptom clusters referring to Disturbances in Self-Organization (DSO) of CPTSD (affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbed relationships). Respondents are asked to indicate the degree of their impairment in functioning in social, work, and other important areas of life in relation or due to the PTSD and DSO symptom clusters. The ITQ items are measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” (0) to “Extremely” (4). The presence of a symptom is indicated by a score of 2 (“Moderately”) or higher. PTSD diagnosis requires the endorsement of one of two symptoms from each PTSD cluster, plus endorsement of functional impairment associated with these symptoms. Diagnosis of CPTSD requires the endorsement of one of two symptoms from each of the six PTSD and DSO symptom clusters, plus the endorsement of functional impairment associated with these symptoms. The ICD- 11 structure specifies that a person may only receive a diagnosis of PTSD or CPTSD, but not both [55].

Reliable Change Index and Clinically Significant Change Margin

In this study, we used the Reliable Change Index (RCI) and the Clinically Significant Change (CSC) Margin to determine whether PTSD symptoms change indicates reliable and clinically significant change [56].

Procedure

Enrollment, Assessments, Data Collection, and Confidentiality of Data

Participants were referred to the study through CAFEMIN’s initial mandatory intake process, which includes screening for PTEs pre-migration and during the migration journey. The screening process was conducted by social workers. Participants completed the instruments in person and on an individual basis during distinct assessment moments. Due to the low-resourced setting, the Specialized Mental Health Professionals (SMHPs) who administered the treatment intervention were also formally trained in all the instruments’ administrations. The SMHPs administered the protocol, conducted T1 pre-treatment assessment, or administered T2 and T3 assessments in rotation, meaning, one SMHP would conduct the pre-treatment assessments, another SMHP would administer the protocol, and another would conduct the post-treatment and follow-up assessments, and would change roles for each group of participants, when possible.

The SMHPs, during T1 pre-treatment assessment conducted the intake interview, collected demographic data (e.g., name, age, gender), assessed potential participants for eligibility based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, obtained signed informed consent from the participants, conducted the pre- treatment application of instruments, and enrolled participants in the study. The SMHPs, specially trained in how to identify the Index Event, also assisted the participants in identifying the pathogenic memory of their worst adverse experience of their entire lives, pre-migration (including childhood), during the migration journey, or recent or ongoing traumatic stress situations, to be treated with the ASSYST-G treatment intervention.

Each identified memory (Index Event) was written down by the SMHPs on the Memory Record Sheets used by the participants during the group treatment intervention and the three assessment times to ensure participants were focusing on the same event when they received the treatment intervention and the specific assessment time when they completed the assessment tools. To obtain maximally interpretable PCL-5 scores and ITQ diagnosis statuses, the SMHPs a) discussed with each participant the purpose of the instrument in detail, b) encouraged attentive and specific responding, c) invited participants to read each question carefully before responding and to select the correct answer, d) read each question and distinct answers carefully to those who could not read or write e) clarified their questions about some of the symptoms, such as differentiating between intrusive memories and flashbacks, f) reworded conceptually complex symptoms (i.e., symptoms in the reexperiencing cluster) when necessary, g) reminded participants of the last-week symptom’s time frame, as well as h) to only report symptoms related to the pathogenic memory of their worst adverse experience (Index Event), and not based on their everyday general distress.

During Time 2 (post-treatment assessment, 7 days after treatment), and Time 3 (follow-up assessment, 14 days after treatment), assessments were conducted for all participants by the SMHPs. The data safekeeper independent assessor received the participant’s assessment instruments that were answered during Times 1, 2, and 3.

All data was collected, stored, and handled in full compliance with the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board requirements to ensure confidentiality. Each study participant gave their consent for access to their data, which was strictly required for study quality control. All procedures for handling, storing, destroying, and processing data were in compliance with the Data Protection Act 2018. All the people involved in this research project were subject to a signed professional confidentiality agreement.

Withdrawal from the study and Missing Data

All research participants had the right to withdraw from the study without justification at any time and with assurances of no prejudicial result. If participants decided to withdraw from the study, they were no longer followed up in the research protocol. There were no withdrawals or missing data during this study.

Treatment

The intervention implementation design was based on a symptom-trajectory based stepped care approach, incorporating the concept of massed and brief delivery of treatment interventions. Massed (accelerated, or intensive multiple sessions per day for consecutive days) and brief (six or fewer sessions) interventions are considered optimal in settings in which comprehensive treatment is not feasible, there are high drop-out rates, or limited access to resources [57]. Jarero and Artigas [47] have structured their protocols to be delivered within a symptomtrajectory- based stepped care approach because of their clinical observation and fieldwork experiences administering their protocols during early intervention and ongoing traumatic stress situations, humanitarian fieldwork after natural and man-made disasters, and with vulnerable populations [47].

This approach is supported in the literature regarding effective delivery of trauma-focused mental health interventions to refugees, asylum-seekers, and forcibly displaced people, suggesting that a stepped-care approach, in which low-intensity treatment interventions, such as a group treatment intervention, is provided as a first step in trauma-focused mental health treatment for PTSD, and a higher intensity PTSD-specific treatment intervention is only provided in cases of participant non-response to the group treatment intervention or persistent PTSD symptomology [9,13,18].

This is to facilitate access to PTSD treatment while ameliorating strains on services and MHPs, which is particularly valuable in LMICs and in humanitarian contexts, where access to treatment is low and barriers to treatment is high. Stepped care models have also been proposed in providing PTSD treatment to refugees with more severe symptom presentation as a potential solution to treatment resistance and dropout in this population. Given the support for a stepped-care approach with this population, the study design included the administration of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention and the ASSYST-I treatment intervention as “booster sessions”, if necessary.

Six sessions of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention were administered, with the provision of two sessions per day over three consecutive days. Seven days after the last administration of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention (the sixth session), the PCL-5 and HADS were administered for Time 2. Post-treatment assessment. In case any participant demonstrated PCL-5 scores of 30 or higher, they would receive up to three consecutive “booster sessions” of the ASSYST-I treatment intervention. None of the participants included in the study demonstrated PCL-5 scores requiring “booster sessions”.

Treatment Providers and Treatment Fidelity

All SMHPs were trained in the ASSYST treatment interventions (ASSYST-G and ASSYST-I) through the EMDR Mexico National Association’s Humanitarian Psychosocial and Research Program, named the ASSYST HEART (Humanitarian Emergency ASSYST Response Training) Project. The ASSYST HEART project provides pro-bono trainings in the ASSYST treatment interventions to SMHPs in LMICs or remote areas working directly with populations affected by natural or man-made disasters, geopolitical conflicts, ongoing traumatic stress situations, or working with marginalized populations.

Since the initiation of the ASSYST HEART project in March 2022, as of August 2025, over 11,000 SMHPs from 53 countries have been trained in the ASSYST treatment interventions, simultaneously facilitating the translation of the ASSYST-G and ASSYST-I protocols into 21 different languages [58]. SMHPs provided all participants in the study with the treatment intervention in person at the CAFEMIN migrant and refugee shelter. To protect the identity of the participants, for whom safety and confidentiality are of utmost importance due to organized crime and gang members often searching for or following them, video and audio recordings of sessions were strictly prohibited. SMHPs received ongoing supervision and clinical feedback from the ASSYST HEART Project Leader and Trainer of Trainers through live supervision to facilitate strict observance of all procedural steps of the manualized protocol, ensuring treatment fidelity and adherence to the protocol.

Treatment Description and Treatment Safety

Treatment was provided by SMHPs who were formally trained in the administration of the ASSYST-G and the ASSYST-I treatment interventions. Each participant received an average of 3.33 hours of treatment provided during six ASSYST-G treatment intervention sessions, two times daily, during three consecutive days, at the CAFEMIN migrant and refugee shelter. The ASSYST-G treatment intervention focused on the pathogenic memory of their worst adverse experience, or Index Event, of their entire life, which could be from pre-migration (even childhood), during the migration journey, recent, or present ongoing traumatic stress situations. During this process, participants followed the directions from the team leader and worked quietly and independently on their pathogenic memories. The first treatment session lasted an average of 50 minutes. Subsequent treatment sessions lasted an average of 30 minutes. The time for rest between sessions was 15 minutes. Activities during rest time included eating, talking with friends, calling family, or resting. Participants learned one selfsoothing technique named focused abdominal breathing.

To encompass the whole traumatic stress spectrum, the team leader asked each of the participants to “Please, with your eyes opened or partially closed, run a mental movie of the whole event on your Memory Record Sheets, from right before the beginning until today, or even looking into the future and raise your hand when you have finished.” The initial treatment target was the worst part (specific memory component) of the pathogenic memory associated with the Index Event. In subsequent sessions, the team leader asked participants to run the mental movie again and then to target any other disturbing part (specific memory component) of the memory that was currently disturbing, rating the disturbance, and noticing body sensations.

Participants in this study used the Butterfly Hug (BH) as a self-administered bilateral stimulation method to process the traumatic material. During the BH, participants were instructed to stop when they felt in their body that it had been enough. This instruction allowed for enough sets of bilateral stimulation (BLS) for processing the traumatic material. This helped to regulate the stimulation to maintain the patients in their window of tolerance, allowing for appropriate processing [59,60].

In cases where participants reported no more disturbing parts associated with the Index Event before the sixth administration of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention, they were instructed to choose another event from their life that currently causes them disturbance and focus on it during the treatment intervention. One group session was dedicated to flash-forwards, or mental representations of catastrophic fears of the future because “the mental life of the person experiencing continuous traumatic stress is characterized by preoccupation with thoughts about potential, future traumatic events (possibly informed by imagery derived from prior and immediate exposure of either an indirect or direct nature), rather than with the details of a previous unprocessed event” (p. 91-92).

This phenomenon happened particularly with this population, in which most participants reported distress related to anticipated trauma associated with PTEs they had already experienced, such as kidnapping, sexual violence, physical assault, witnessing murder, or fear of death, detention, or deportation. Participants, clinicians, medical practitioners, and social workers working at the shelter were instructed to report any reported or observed adverse effects, events, or worsening of symptoms during the study to the research project’s Clinical Director. None of the participants showed clinically significant worsening/ exacerbation of symptoms on the PCL-5 or HADS after treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics was used to report ITQ results. Analyses of Repeated Measures and Pairwise Comparisons were conducted. ANOVA analysis includes the three assessment times (T1, T2, T3) for three variables: PCL-5, Anxiety and Depression. The analysis was conducted using a repeated-measures ANOVA to compare the three time points, effect sizes were calculated as eta squared (η²). Pairwise comparisons (T1 vs. T2, T2 vs. T3) was conducted using paired t-tests, Cohen’s d is included in each case to report the effect sizes.

Results

ITQ Diagnostic Status

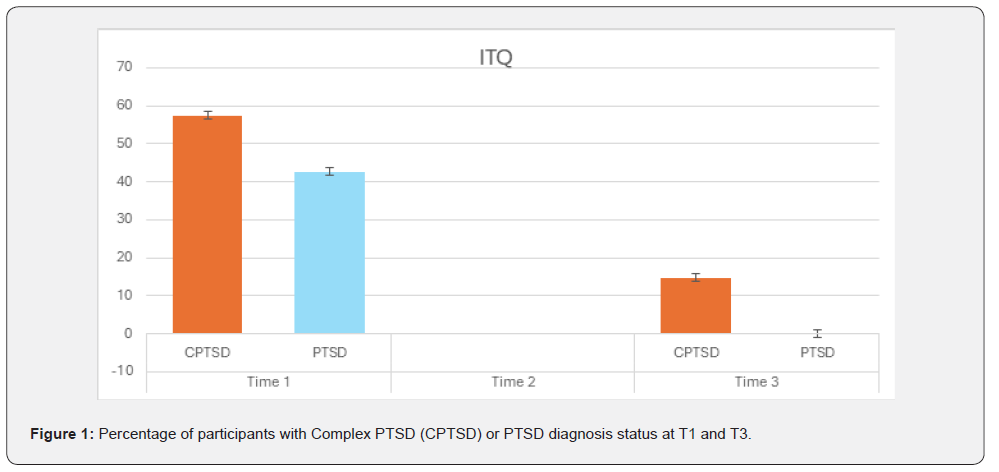

At T1, 54 participants were assessed, 31 (57.4%) met criteria for Complex- PTSD (CPTSD) and 23 (42.6%) for PTSD. By T3, only 8 participants (14.8%) still met diagnostic criteria for CPTSD, and none met criteria for PTSD, indicating a high rate of diagnosis status remission. See Figure 1.

Examples of the Treated Pathogenic Memories

Participants reported a wide range of traumatic experiences, including sexual violence, armed assault, forced displacement, loss of loved ones, and threats with weapons. Despite high baseline trauma load (e.g., Participant 25: “when they killed my son”; Participant 54: “my stepfather abused me since I was 7, threatening me with a gun”), most showed marked improvement in trauma-related symptoms and daily functioning at T2 and T3.

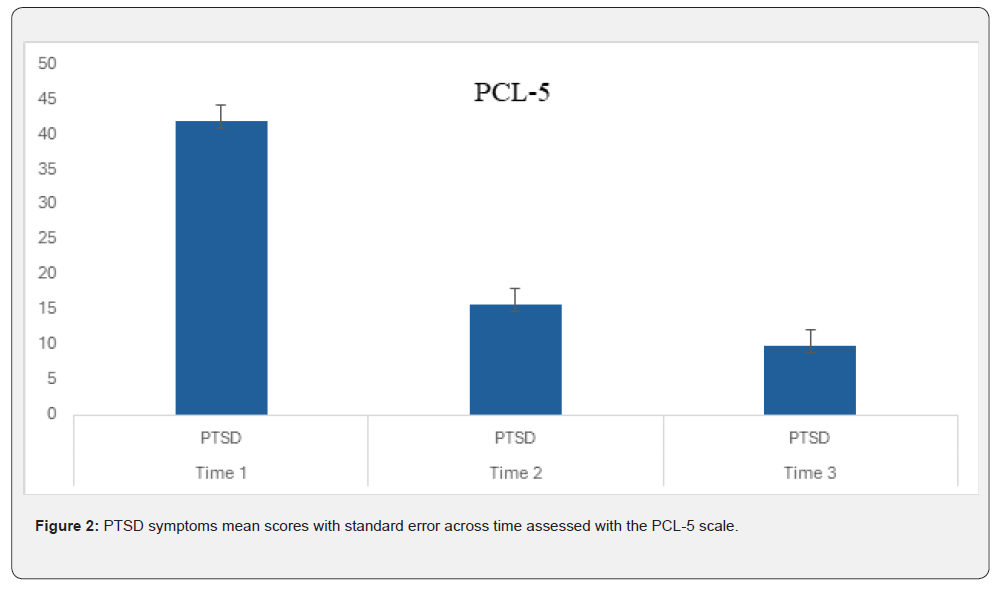

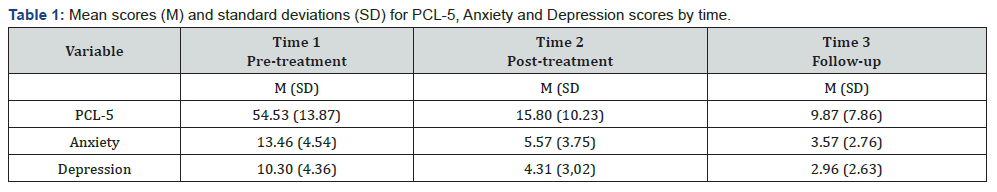

Effect on PTSD symptoms

A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time on PCL-5 scores, F (2, 102) = 58.67, p < .001, η² = 0.53, indicating a large effect size. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed significant reductions in PCL-5 scores from T1 (M = 54.43, SD = 13.87) to T2 (M = 15.80, SD = 10.23), t (53) = 18.67, p < .001, d = 2.58, and from T2 to T3 (M = 9.87, SD = 7.86), t (53) = 6.89, p < .001, d = 0.95 showing a large effect size in both comparisons. See Table 1 and Figure 2.

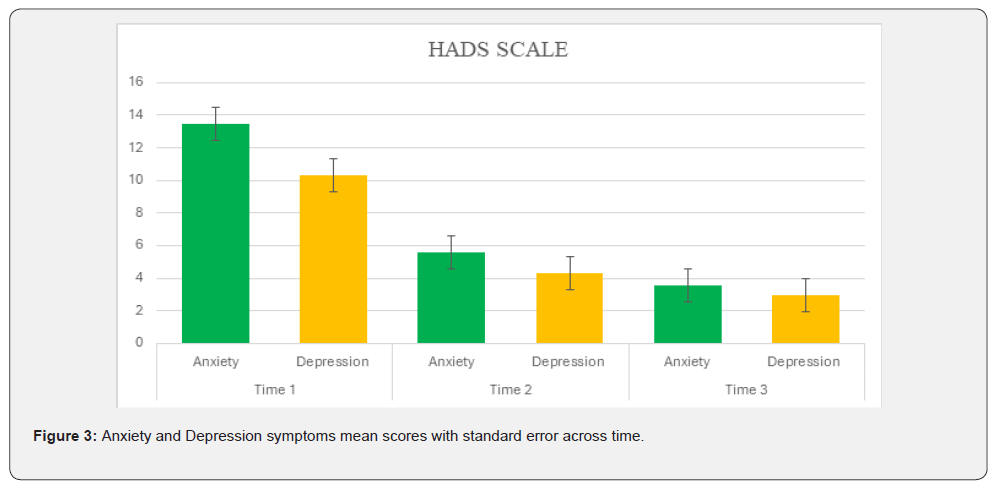

The two subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) showed the following results: Effect on Anxiety Symptoms

The repeated-measures ANOVA also indicated a significant effect of time on anxiety scores, F (2, 102) = 29.84, p < .001, η² = 0.37. Pairwise comparisons revealed significant decreases in anxiety scores from T1 (M = 13.46, SD = 4.54) to T2 (M = 5.57, SD = 3.75), t (53) = 12.34, p < .001, d = 1.71, and from T2 to T3 (M = 3.57, SD = 2.76), t (53) = 4.56, p < .001, d = 0.63, indicating a large effect size. See Table 1 and Figure 3.

Effect on Depression Symptoms

Similarly, there was a significant effect of time on depression scores, F (2, 102) = 21.45, p < .001, η² = 0.30. Pairwise comparisons demonstrated significant reductions in depression scores from T1 (M = 10.30, SD = 4.36) to T2 (M = 4.31, SD = 3.02), t (53) = 9.87, p < .001, d = 1.37, and from T2 to T3 (M = 2.96, SD = 2.63), t (53) = 3.21, p = .002, d = 0.44 with large and medium effect sizes respectively. See Table 1 and Figure 3.

Discussion

This one-arm pre-post repeated measures study had two objectives: 1) evaluate the safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization for Groups (ASSYST-G) treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression symptoms and 2) to assess the effectiveness of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention in the PTSD or CPTSD diagnosis status remission in the refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced population in transit through Mexico to the USA border.

A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant differences across the three time points (T1, T2, T3) for all variables: PCL-5, F(2, 102) = 58.67, p < .001, η² = 0.53; Anxiety, F(2, 102) = 29.84, p < .001, η² = 0.37; Depression, F(2, 102) = 21.45, p < .001, η² = 0.30. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using paired t-tests indicated significant reductions in scores from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3 for all variables. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranged from medium to large, with the largest effects observed between T1 and T2 (PCL- 5: d = 2.58; Anxiety: d = 1.71; Depression: d = 1.37). These results demonstrate significant improvements in all three variables (PCL- 5, Anxiety, Depression) over time, with large effect sizes observed for the comparisons from T1 to T2 with moderate to large effect sizes from T2 to T3.

These findings suggest that the treatment intervention had a substantial impact on reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. The reduction in PCL-5 scores is particularly noteworthy, as it indicates a marked decrease in PTSD symptom severity. It is important to highlight that in the post-treatment assessment, no participants met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, anxiety, or depression according to the criteria of the applied instruments. The reduction in ITQ scores from T1 to T3 supports the intervention’s effectiveness as a brief, scalable treatment for trauma-affected populations, particularly among those with complex trauma histories.

Conclusion

Results of this study show that six administrations of the ASSYST-G treatment intervention during three consecutive days contributed to PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptom reduction and PTSD or CPTSD diagnosis status remission in transient refugee, asylum-seeker, and forcibly displaced populations in transit through Mexico to the US border. These findings contribute to the current literature, indicating that an evidencebased, massed, brief, low-intensity, group trauma-focused intervention can not only contribute to symptom reduction but also to remission of diagnosis status in this population during the migration phase. This is essential for trauma-focused treatment of this population, who have higher severity and exposure to PTEs and ongoing traumatic stress situations and typically have lower access to high-quality trauma-focused treatment due to previously mentioned specific treatment barriers.

These results align with those of previous ASSYST-G treatment intervention studies involving other populations. The ASSYST-G treatment intervention was not altered or adapted for the population or for the CPTSD construct, demonstrating the generalized effectiveness of the protocol. This is also significant because it shows that adaptations of the protocol are not necessary for this population, nor for those within the population who meet the diagnostic criteria for the CPTSD construct. From clinical observation and self-report of the participants in this study, not only was there a reduction in specific PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms, but the participants, social workers, and medical staff reported that the participants in the study were able to make informed decisions, less emotionally reactive, take better care of their children, successfully carry out immigration interviews, make medical appointments, and look for and obtain work. We can theorize that this is a subsequent effect of the ASSYST treatment intervention, which aims to regulate the nervous system and reestablish the pre-frontal cortex’s executive functions.

Our hope is that this study will contribute to the efforts being made to find appropriate and effective trauma-focused treatment interventions for this high-needs population, not just in HICs, once they are already resettled, but also during the migration journey, so that the suffering associated with PTSD or CPTSD can be alleviated as soon as possible, facilitating successful outcomes during resettlement. And ultimately, stakeholders such as policymakers, public health systems, organizations, and even clinicians will facilitate trainings and supervision in the application of the ASSYST treatment interventions with this extremely vulnerable population that has experienced disproportionate suffering caused by traumatic experiences and minimal access to resources that can alleviate this suffering.

Limitations and Future Directions

The follow-up assessment at 14 days and lack of control group, due to ethical and logistical reasons (the transient nature of the population, with temporary and unpredictable stays at the shelter, and shelter social work and medical staff requesting a lack of control group to ensure all of those who require PTSD specialized treatment receive treatment), are limitations of this study. To further enhance the robustness of this study, we recommend conducting multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCT)s with an intention-to-treat analysis, with larger samples, and follow-up assessment at three- months, following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 Statement and the Standard Protocol Items Recommendation for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 checklist when safe, feasible, and ethical with this population.

References

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Who We Protect. UNHCR.

- Apers H, Van Praag L, Nöstlinger C, Agyemang C (2023) Interventions to improve the mental health or mental well-being of migrants and ethnic minority groups in Europe: A scoping review. Glob Ment Health (Camb) 10: e23.

- World Health Organization (2025) Refugee and Migrant Mental Health.

- Cécile Rousseau and Rochelle L Frounfelker (2018) Mental health needs and services for migrants: an overview for primary care providers. Journal of Travel Medicine 1–8.

- Hameed S, Sadiq A, Din AU (2018) The Increased Vulnerability of Refugee Population to Mental Health Disorders. Kans J Med. 11(1): 1-12.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA

- Romero DE, Anderson A, Gregory JC, Potts CA, Jackson A, et al. (2020) Using neurofeedback to lower PTSD symptoms. NeuroRegulation 7(3): 99-106.

- Bryant RA, Nickerson A, Morina N, Liddel B (2023) posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 19: 413-436.

- Jowett S, Argyriou A, Scherrer O, Karatzias T, Katona C (2021) Complex post-traumatic stress disorder in asylum seekers and victims of trafficking: treatment considerations. BJPsych Open 7(6): e181.

- De Silva U, Glover N, Katona C (2021) Prevalence of complex post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees and asylum seekers: systematic review. BJPsych Open 7(6): e194.

- World Health Organization (2022) ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision).

- Angela N, Belinda L, Anu A, Jessica C (2024) Trauma and Mental Health in Forcibly Displaced Populations: An International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Briefing Paper.

- Ad de Jongh, Iva Bicanic, Suzy Matthijssen, Benedikt L Amann, Arne Hofmann, et al. (2019) The Current Status of EMDR Therapy Involving the Treatment of Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J EMDR Pract and Res 13: 284-290.

- De Jongh A & Hafkemeijer LCS (2024) Trauma-focused treatment of a client with Complex PTSD and comorbid pathology using EMDR therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology 80(4): 824–835.

- Hyland P, Shevlin M, Brewin CR (2023) The memory and identity theory of ICD-11 complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Rev 130(4): 1044-1065.

- Giulia Turrini, Federico Tedeschi, Pim Cuijpers, Cinzia Del Giovane, Ahlke Kip, et al. (2021) A network meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for refugees and asylum seekers with PTSD: BMJ Global Health 6(6): e005029.

- Wippich A, Howatson G, Allen Baker G, Farrell D, Kiernan M, et al. (2024) Eye movement desensitization reprocessing as a treatment for PTSD in conflict-affected areas. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 16(S3): S561–S567.

- Clemence Due, Trephina Gartley & Anna Ziersch (2024) A systematic review of psychological group interventions for adult refugees in resettlement countries: development of a stepped care approach to mental health treatment. Australian Psychologist 59(3): 167-184.

- (2023) US-Mexico Border World’s Deadliest Land Migration Route. IOM UN Migration.

- (2021) Challenges faced by migrant women in transit through Mexico. Migrant Documentation Project.

- Shapiro F (2018) Eye movements desensitization and reprocessing. Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (Third edition). Guilford Press.

- Becker Y, Estévez ME, Pérez MC, Osorio A, Jarero I, et al. (2021) Longitudinal Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial on the Provision of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Remote for Groups to General Population in Lockdown During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 16(2): 1-11.

- Smyth Dent K, Becker Y, Burns E, & Givaudan M (2021). The Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Remote Individual (ASSYST-RI) for TeleMental Health Counseling After Adverse Experiences. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 16(2): 1-7.

- Magalhães SS, Silva CN, Cardoso MG, Jarero I, Pereira Toralles MB (2022) Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Remote for Groups Provided to Mental Health Professionals During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Journal of Medical and Biological Science 21(3): 637-643.

- Mainthow N, Pérez MC, Osorio A, Givaudan M & Jarero I (2022) Multisite Clinical Trial on the ASSYST Individual Treatment Intervention Provided to General Population with Non-Recent Pathogenic Memories. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 19(5).

- Smith S, Todd M, Givaudan M (2023) Clinical Trial on the ASSYST for Groups Treatment Intervention Provided to Syrian Refugees living in Lebanon. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 20(2): 1-8.

- Mainthow N, Zapien R, Givaudan M & Jarero I (2023) Longitudinal Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial on the ASSYST Individual Treatment Intervention Provided to Adult Females with Adverse Childhood Experiences. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 20(3): 556040.

- Magalhãe SS, Guimarães, ACF Silva, CN Souza, JSS Carasek L, et al. (2023) Randomized Clinical Controlled Trial on the ASSYST Treatment Intervention Provided to Public Sector Workers During the COVID19 Pandemic. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 20(5): 1- 11.

- Carretero KP, Delgadillo A, Villarreal AM, Roque JP, Poiré A, et al. (2023) Randomized Controlled Trial on the ASSYST Treatment Intervention with Female Children Polytraumatized by Adverse Childhood Experiences, Neglect and Maltreatment. Academic Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatology 12(5): 1-9.

- Ross J, Navarro F, Mainthow N, Givaudan M, Jarero I (2024) Breast and Cervical Cancer-Related PTSD: Randomized Controlled Trial on the ASSYST Treatment Intervention. Cancer Therapy and Oncology International Journal 25(5): 1-11.

- Martínez Cáceres G & Premuda Conti P (2024) ASSYST-Individual Adapted for the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 18(3): 129-142.

- Miteva Ivanka, Spasova Anna, Shtereva Katcarowa, Sofia, Mainthow Nicolle, et al. (2025) A one-day ASSYST Group Treatment Intervention to Victims of Flood in Bulgaria. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 23(1).

- Smyth Dent KL, Fitzgerald J, Hagos Y (2019) A Field Study on the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress Provided to Adolescent Eritrean Refugees Living in Ethiopia. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 12(4): 1-12.

- Molero RJ, Jarero I, Givaudan M (2019) Longitudinal Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial on the Provision of the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress to Refugee Minors in Valencia, Spain. American Journal of Applied Psychology 8(4): 77-88.

- Jarero I, Givaudan M, Osorio A (2018) Randomized Controlled Trial on the Provision of the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol Adapted for Ongoing Traumatic Stress to Female Patients with Cancer-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 12(3): 94-104.

- Osorio A, Pérez MC, Tirado SG, Jarero I, Givaudan M (2018) Randomized Controlled Trial on the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress with Adolescents and Young Adults Patients with Cancer. American Journal of Applied Psychology 7(4): 50-56.

- Smyth Dent K, Walsh SF, Smith S (2020) Field Study on the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress with Female Survivors of Exploitation, Trafficking and Early Marriage in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 15(3): 1-8.

- Vock S, et al. (2024). Group Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) for Chronic Pain Patients. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1264807.

- Jarero I, Artigas L, Luber M (2011) The EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents: Application in a Disaster Mental Health Continuum of Care Context. J EMDR Practice Res 5(3): 82-94.

- Jarero I, Uribe S (2011) The EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents: Brief Report of An Application in a Human Massacre Situation. J EMDR Practice Res 5(4): 156-165.

- Jarero I, Uribe S, Artigas L, Givaudan M (2015) EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents: A Randomized Controlled Trial in a Technological Disaster context. J EMDR Practice Res 9(4): 166-173.

- Jarero I, Schnaider S, Givaudan M (2019) EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents and Ongoing Traumatic Stress with First Responders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J EMDR Practice Res 13(2): 100-110.

- Encinas M, Osorio A, Jarero I, Givaudan M (2019) Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial on the Provision of the EMDR-PRECI to Family Caregivers of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychol BehavSci Int J 11(1): 1-8.

- Estrada BD, Angulo BJ, Navarro ME, Jarero I, Sánchez Armass O (2019) PTSD, Immunoglobulins, and Cortisol Changes after the Provision of the EMDR- PRECI to Females Patients with Cancer-Related PTSD Diagnosis. Am J Applied Psychol 8(3): 64-71.

- Jiménez G, Becker Y, Varela C, García P, Nuño MA, et al. (2020) Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial on the Provision of the EMDR-PRECI to Female Minors Victims of Sexual and/or Physical Violence and Related PTSD Diagnosis. Am J Applied Psychol 9(2): 42-51

- Jarero I (2021) ASSYT Treatment Procedures Explanation. Technical Report. Research Gate.

- Mainthow N, Pérez MC, Osorio A, Givaudan M, & Jarero I (2022) Multisite Clinical Trial on the ASSYST Individual Treatment Intervention Provided to General Population with Non-Recent Pathogenic Memories. Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal 19(5).

- Walter KH, Otis NP, Kline AC, Miggantz EL, Hunt WM, et al. (2025) Was it helpful? Treatment outcomes and practice assignment adherence and helpfulness among U.S. service members with PTSD and MDD. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Advance online publication. PTSDpubs ID: 1646642

- Darnell CB, et al. (2025) Psychometric evaluation of the weekly version of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 Sage.

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, et al. (2016) Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders- Firth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess 28(11): 1379-1391.

- Franklin CL, Raines AM, Cucurullo LA, Chambliss JL, Maieritsch KP, et al. (2018) 27 ways to meet PTSD: Using the PTSD-checklist for DSM-5 to examine PTSD core criteria. Psychiatry Research 261: 504-507.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6): 361-370.

- Ying Lin C, Pakpour AH (2017) Using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) on patients with epilepsy: Confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch models. Seizure (45): 42-46.

- Cloitre M, Shevlin M, Brewin C, Bisson J, Roberts N, et al. (2018) The international trauma questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Actapsychiatrica Scandinavica 138(6): 536-546.

- Marx BP, Lee DJ, Norman SB, Bovin MJ, Sloan DM (2021) Reliable and Clinically Significant Change in the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 Among Male Veterans. Psychological Assessment. Advance online publication 34(2): 197-203.

- Schuster Wachen J (2024) Massed and Brief Treatments for PTSD. PTSD Research Quarterly. 35(3): 1050-1835

- EMDR Mexico National Association. Assyst Heart Humanitarian Project.

- Ogden P, Minton K, Pain C (2006) Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York, NY: Norton.

- Siegel DJ (1999) The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Eagle Gillian & Kaminer Debra (2013) Continuous Traumatic Stress: Expanding the Lexicon of Traumatic Stress. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 19(2), 85–99.