Abstract

Purpose

To review and evaluate methods for quantifying individual freesugar intake, identify key limitations and gaps, and inform development of a rapid, culturally adapted assessment tool for Chinese adolescents to support publichealth interventions.

Design/Methodology/Approach

We conducted a literature review of studies on the assessment of free sugar intake, examining intake assessment methods, the sugar classification, the range of food and beverage types captured, dataprocessing procedures, underlying food composition sources, and operational factors affecting validity, reliability and feasibility for rapid screening applications.

Findings

Three major challenges were identified. (1) Existing methods are timeconsuming, labourintensive and depend on food composition data that rarely include freesugar values, complicating calculation. (2) Different methods yield different intake estimates and identify different primary food sources, producing inconsistent results and preventing crossstudy comparison. (3) Few practical, userfriendly tools exist to support largescale screening, public selfmonitoring or rapid field assessment; no localized validated instrument for free sugar exists in China. International brief tools show promise but require cultural adaptation for China’s unique highsugar foods and beverage patterns. Digital technology offers an opportunity to improve accessibility and efficiency.

Research limitations/implications

Priorities include developing and validating concise, culturally tailored rapid instruments for adolescents, integrating freesugar data into national food composition tables, and deploying validated tools via digital platforms for surveillance and interventions.

Originality/value

This is the first review to examine methodological approaches for estimating individual freesugar intake and identify priority actions toward a standardized rapid assessment toolkit for Chinese adolescents.

Keywords:free sugar; intake assessment; adolescents; dietary survey

Introductıon

“Free sugars” are defined as monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods by manufacturers, cooks or consumers, as well as sugars naturally present in honey, syrups and fruit juices. The World Health Organization (WHO) put forward the concept of free sugars as early as 2003 and has consistently advocated reducing the intake of free sugars rather than other types of sugars. This is because sugars in whole fruits and vegetables (intrinsic sugars) are enclosed within plant cell walls, are digested more slowly, take longer to enter the bloodstream than free sugars, and have far less impact on obesity and dental caries than free sugars do [1].

Intake of free sugars can displace foods that provide more appropriate nutrients and energy, leading to unhealthy diets, weight gain, and increased risk of noncommunicable diseases. There is a clear association between lower free sugar intake and weight loss in both adults and children. WHO recommends reducing free sugar intake throughout the life course; for both adults and children, free sugars should provide less than 10% of total energy intake and further reducing this to below 5% of total energy would deliver additional health benefits [1].

In developed countries/regions such as Europe and North America, epidemiological data show that free sugar intake as a percentage of total energy is about 13.5% in the United States, 7–11% in Europe, 13.2% in Latin America, and 13.3% in Canada. The Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents [2] also highlight the need to limit sugar intake and specifically distinguish added sugars (a type of free sugar), pointing out that excessive intake of added sugars increases the risk of dental caries and overweight/ obesity. Internationally and domestically, there is growing recognition of the importance of using a precise sugar concept.

Setting a blanket upper limit for all sugars, including intrinsic sugars in fruit and vegetables, can lead to misguided health behaviors, such as reduced fruit and vegetable consumption, thereby undermining health promotion efforts. In public health research, failure to distinguish free sugars can easily lead to misjudgment of nutritional and health status and, consequently, to inappropriate recommendations.

At the same time, in China, unhealthy eating behaviors are becoming increasingly common among residents, especially children and adolescents, alongside a rapid rise in obesity, diabetes and other chronic diseases. School age is a critical period for establishing health beliefs and forming healthy eating behaviors. Developing healthy dietary habits and lifestyles in childhood can bring lifelong benefits [2]. Studies of the main dietary sources of free sugar in China-sugar-sweetened beverages and baked goodsshow that among all age groups, adolescents aged 13–17 years have the highest free sugar intake [3-4].

Therefore, this project focuses on adolescents and aims to develop public health strategies to reduce free sugar intake in this population. To achieve this goal, we plan to design a core technical assessment tool: a rapid assessment scale for free sugar intake. The present review aims to lay the theoretical foundation for the development of such tools by systematically summarizing the existing literature.

Methods

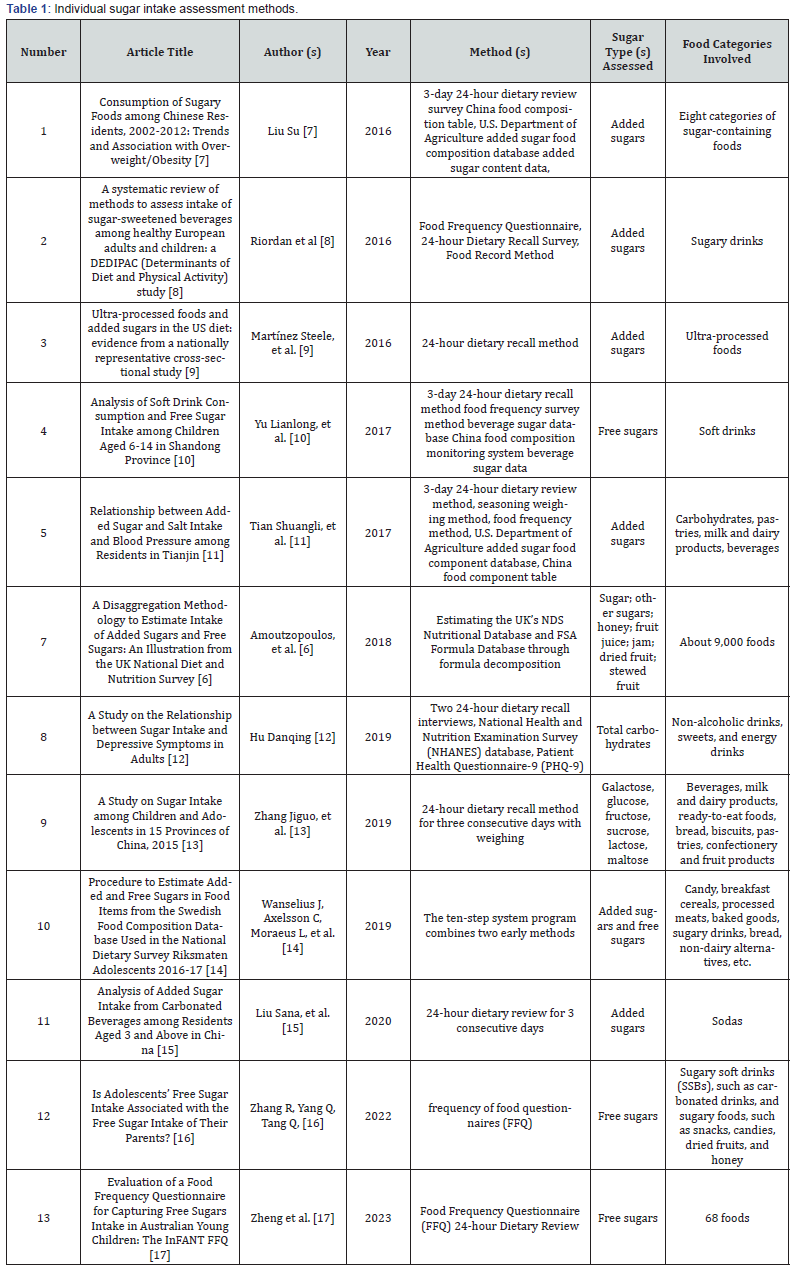

This review is based on a systematic search of Chinese and English databases (including PubMed, CNKI, Wanfang, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, Nature) to identify original research, review articles and methodological papers related to the assessment of free sugar and added sugar intake. Search terms included “free sugar,” “added sugar,” “intake assessment,” “dietary survey,” “sugar intake assessment”. We focused on the validity and reliability of assessment tools, their application scenarios, and their strengths and limitations. In total, we included 13 representative studies, whose basic characteristics are summarized in (Table 1).

Results

Although the precise concept of free sugar is crucial for assessing health status and improving health behavior patterns, the techniques and methods used to assess free sugar intake lag far behind and face several technical difficulties.

First, assessing the intake of sugars, including free sugars, is time-consuming and complex. At present, most assessments of sugar and free sugar intake rely on 24-hour dietary recall surveys conducted on different numbers of days (e.g., one or three 24-hour recalls; see Table 1), as well as food frequency questionnaires, disaggregation methods and 10-step systematic approaches. These methods require extensive calculation and analysis based on food composition databases, making the workload very heavy. Because very few databases contain data on free sugar, data retrieval and calculation are extremely challenging. Many studies still focus on added sugars and total sugars in high-sugar foods, with relatively few specifically assessing free sugar.

Multiple studies have estimated intakes of various types of sugars and from different food sources, including total sugar or components of total sugar, or sugar-containing foods and beverages [5]. Sugars assessed include galactose, glucose, fructose, sucrose, lactose, maltose, free sugar, added sugar, Non- Milk Extrinsic Sugars (NME), and total sugars. Food sources include beverages such as fruit juice, sugar products such as jams, cakes and pastries, milk and dairy products, ready-to-eat foods, bread, biscuits, fruit products, and more [6].

Data sources are diverse and include: the USDA Added Sugars Database (for added sugar content), data on soft drink and sugar-sweetened juice consumption from the China Health and Nutrition Survey, the Chinese Food Composition Tables, nationally representative dietary surveys from various countries, nationally representative multi-sectoral surveys in the United States (such as the Nationwide Food Consumption Survey and NHANES), and eleven representative national surveys from Belgium, France, Denmark, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK. The UK has also established a free sugar database based on recipe disaggregation for seven sugar components (table sugar, other sugars, honey, fruit juice, jam, dried fruit and stewed fruit), covering around 9,000 foods.

These studies, conducted within 10 years using a variety of methods to assess sugar intake, demonstrate that accurately estimating individual free sugar intake is important for many types of research. Using a standardized method to assess individual free sugar intake would greatly facilitate comparison and synthesis across studies. However, the Chinese Food Composition Tables currently do not include data on free sugars, and China still lacks a representative, feasible and accurate method for assessing free sugar intake.

Second, different assessment methods produce different results regarding both intake levels and main dietary sources.

The Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents [2] report that the average daily intake of added sugars in China in 2012 was about 30 g. A 2014 survey showed that among children and adolescents aged 3–17 years who regularly drink beverages, the energy from added sugars in beverages alone exceeded 5% of total energy intake and was rising, surpassing the WHO recommended limit. Sugar-sweetened beverages were identified as the main source of added sugars in children and adolescents. However, Liu Su’s study reported that the average daily intake of added sugars among Chinese residents in 2012 was 18.8 g/day, still at a relatively low level [7], with cakes and desserts being the main source of added sugars. While reducing free sugar intake has attracted attention, only by accurately identifying the main sources and intake levels of free sugars can we design effective interventions.

Third, existing assessment tools lack practicality, which further hinders the spread of the free sugar concept and the implementation of interventions. In the era of digital health and popular mobile apps, rapid assessments via software to help individuals understand their health and dietary intake have become very common. However, the lack of reliable, user-friendly assessment tools prevents consumers from taking proactive steps to manage their health and greatly increases the human and time costs for health management institutions. If initial assessment and awareness-raising are difficult to carry out, subsequent health education, behavior change and intervention measures are also hard to implement.

Currently, there is no specific assessment tool for measuring free sugar intake in China. However, there is a brief questionnaire developed internationally called the Dietary Fat and Free Sugar- Short Questionnaire (DFS), which includes an assessment of free sugar intake. This tool was released in 2012 and consists of 26 items. It serves as a simple and quick way to screen individuals, conduct self-assessments, and facilitate large epidemiological research studies. In 2024, a study conducted by Tabis and colleagues validated the reliability and effectiveness of the Polish version of the DFS. The research involved 291 participants aged between 14 and 70 years. The findings indicate that the Polish version of the DFS is a reliable and effective tool for evaluating the intake of foods high in saturated fat and free sugars. Given the limitations regarding the regions and ages of the study sample, it is necessary to explore the applicability of the DFS in other regions and across different age groups to enhance its effectiveness and inform targeted prevention measures and nutritional intervention strategies.

Discussion

This review systematically reveals three core issues currently faced in the field of free sugar intake assessment: methodological complexity, lack of data consistency, and scarcity of practical tools. These collectively hinder the effective control over free sugar intake in China.

There is an urgent need to develop localized rapid assessment tools for free sugar intake that account for cultural differences. Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ) are commonly used tools for dietary assessment, but their development, validation, and application heavily rely on specific dietary cultures [18]. While the DFS questionnaire offers valuable insights, its direct application to the Chinese population, particularly among adolescents, may face significant limitations. China’s dietary patterns include many high-free sugar foods that are culturally distinctive, such as milk tea, sweetened iced tea, and unique desserts, which may not be well covered in foreign assessments. Thus, based on international experience, it is essential to strictly adhere to measurement standards and develop assessment tools that are tailored to the dietary characteristics of Chinese adolescents to ensure accurate and effective evaluation outcomes [18].

The rapid development of information technology presents an opportunity to address the practical usability of these assessment tools. Transforming scientifically validated assessment tools into user-friendly mobile applications or online questionnaires can significantly lower the barrier to usage, promote large-scale screenings, and enable public self-monitoring [19-20]. This approach could not only enhance the efficiency of data collection but also improve user engagement and health awareness through immediate feedback, thus saving public health resources and facilitating subsequent interventions such as health education and behavior change [21-22].

Conclusions and Recommendations

Constructing a scientific and straightforward assessment tool for free sugar intake is crucial for controlling sugar consumption, especially for adolescents. This review clarifies the limitations of existing assessment methods and emphasizes the urgency of developing future tools.

To address the gaps, we recommend the following actions

First, develop a concise, culturally adapted rapid assessment instrument, especially for adolescents, that targets the primary high-free-sugar food and beverage items identified from national surveys and market data, ensures age-appropriate phrasing and portion-size aids, and is available in both paper and digital formats.

Second, utilize mobile internet technology to develop these tools into a digital platform, enhancing accessibility, convenience, and data collection efficiency;

Third, advocate for the inclusion of free sugar data in the national food composition table to provide a solid data foundation for all related research and assessments.

Fourth, use the validated tool in representative surveillance and intervention studies, school-based monitoring, product reformulation tracking and behavior-change trials, to generate timely evidence on prevalence, major sources and intervention impact.

Together, these measures will reduce methodological heterogeneity, lower operational barriers to measurement, and produce high-quality data necessary to guide and evaluate policy and programmatic efforts to reduce free-sugar consumption.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, “Development of Scientific Data Sharing and Mining Technologies and Systems for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control” (No. 2023ZD0509702).

Disclosure

The views expressed are those of the authors alone.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (2015) Guidelines: sugar intake for adults and children.

- China Nutrition Society (2022) China Dietary Guidelines for School-Age Children 2022. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House.

- Qu P, Dechun L, Tongwei Z, Feng P, Jiang L, et al. (2021) Assessment of free sugar intake and analysis of baked food consumption among urban residents aged 3 and above in China. Zhongguo Shipin Weisheng Zazhi 33(3): 332-337.

- Pan F, Dechun L, Tongwei Z, Weifeng M, Dong L, et al. (2022) Assessment of sugar-sweetened beverages consumption and free sugar intake among urban residents aged 3 and above in China.

- Committee for the Promotion of Healthy China Action (2019) Healthy China Action (2019-2030).

- Amoutzopoulos B, Steer T, Roberts C, Cole D, Collins D, et al. (2018) A Disaggregation Methodology to Estimate Intake of Added Sugars and Free Sugars: An Illustration from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Nutrients 10(9): 1177.

- Liu S (2016) Consumption Status and Changes of Sugary Foods by Chinese Residents from 2002 to 2012 and Its Relationship with Overweight and Obesity. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Riordan F, Ryan K, Perry IJ, Schulze MB, Andersen LF, et al. (2017) A systematic review of methods to assess intake of sugar-sweetened beverages among healthy European adults and children: a DEDIPAC (DEterminants of DIet and Physical Activity) study. Public Health Nutrition 20(4): 578-597.

- Martínez SE, Baraldi LG, Louzada MLC, Moubarac JC, Mozaffarian D, et al. (2016) Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6(3): e009892.

- Yu L, et al. (2017) Analysis of the soft drink consumption and free sugar intake in 6~14-year-old children in Shandong China. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care 25(11): 1166-1169.

- Tan S, Peng X, Zi-bing W, Wei L, Xiao-duan X, et al. (2017) Association between added sugars and salt intake with blood pressure in Tianjin residents. Chinese Journal of Disease Control 21(10): 974-978.

- Hu D (2019) Adults carbohydrate intake and the relationship of depression research. Qingdao University.

- Zhang J, et al. (2019) A Study on Sugar Intake of Children and Adolescents in 15 Provinces of China in 2015. In: Nutrition Research and Clinical Practice - Abstracts of the 14th National Congress of Nutrition Science and the 11th Asia-Pacific Clinical Nutrition Congress, as well as the 2nd Global Conference of Chinese Nutrition Scientists. Institute of Nutrition and Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention pp. 210.

- Wanselius J, Axelsson C, Moraeus M, Berg C, Mattisson I, et al. (2019) Procedure to Estimate Added and Free Sugars in Food Items from the Swedish Food Composition Database Used in the National Dietary Survey Riksmaten Adolescents 2016-17. Nutrients 11(6): 1342.

- Liu S, Zhang T, Pan F, Li J, Luan D, et al. (2020) Analysis on sugar intake from carbonated beverages aged 3 years and above of China. Zhongguo Shipin Weisheng Zazhi 32(5): 556-560.

- Zhang R, Yang Q, Tang Q, Xi Y, Lin Q, et al. (2022) Is Adolescents' Free Sugar Intake Associated with the Free Sugar Intake of Their Parents? Nutrients 14(22): 4741.

- Zheng M, Silva M, Heitkonig S, Abbott G, McNaughton SA, et al. (2023) Evaluation of a Food Frequency Questionnaire for Capturing Free Sugars Intake in Australian Young Children: The InFANT FFQ. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(2): 1557.

- Cade J, Thompson R, Burley V, Warm D (2002) Development, validation and utilisation of food-frequency questionnaires – a review. Public Health Nutrition 5(4): 567-587.

- Francis H, Stevenson R (2013) Validity and test-retest reliability of a short dietary questionnaire to assess intake of saturated fat and free sugars: a preliminary study. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics 26(3): 234-242.

- Malik VS, Hu FB (2019) Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Cardiometabolic Health: An Update of the Evidence. Nutrients 11(8): 1840.

- Tabiś K, Mackow M, Nowacki D, Poprawa R (2024) Adapting the Dietary Fat and Free Sugar Short Questionnaire: A Comprehensive Polish Modification for Enhanced Precision in Nutritional Assessments. Nutrients 16(4): 503.

- Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J (2014) Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 346: e7492.