Abstract

Overweight, obesity and diabetes represent major global public health challenges. The persistent prevalence of these conditions underscores the limitations of traditional, one-size-fits-all dietary guidelines. This review explores the paradigm of Personalised Nutrition (PN) as a more effective approach to diet therapy, arguing that individual variation in dietary response is a key for the failure of universal recommendations. We examine the scientific foundations of PN, focusing on the critical interplay between genetic predisposition, gut microbiota and dietary intake critical interplay between genetic predisposition, gut microbiota and dietary intake. The discussion highlights how specific genetic polymorphisms (e.g., in the FTO, TCF7L2, and APOA2 genes) influence metabolism, satiety and cardiovascular risk, thereby modulating the effectiveness of different dietary patterns such as low-fat, low-carbohydrate, and Mediterranean-style diet. Furthermore, the gut microbiota is reviewed as a dynamic metabolic organ that affects energy harvest, the production of metabolites like Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs), and systemic inflammation and glycaemic control. The complex synergistic relationship between host genetics and the microbiome is exemplified by pathways such as the production of Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) production. This review also outlines a practical framework for translating this evidence into clinical practice by integrating data from genetic testing, microbiota profiling, and continuous glucose monitoring via digital platforms. We address potential challenges and ethical considerations, including research gaps, data privacy, and equitable access. Finally, we present future perspectives on the personalised utilisation and recommendations for their functional foods and natural sweeteners, concluding that moving beyond genetic advice to tailored dietary recommendations holds significant potential for developing more sustainable and effective strategies to combat obesity, diabetes, and related cardiometabolic diseases.

Keywords:Public health; nutrition; genetic blueprint; microbiota; dietary intake; low-calorie

Introductıon

The global surge of metabolic syndrome, particularly overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, represents one of the most significant public health crises of the present century [1-2]. Obesity prevalence has nearly tripled since the 1970s, affecting hundreds of millions of adults worldwide [3]. At the same time, diabetes cases continue to rise, with projections indicating a substantial increase in the coming decades [1-2]. These conditions are closely linked to obesity, which is considered the major driver of diabetes. Furthermore, their co-occurrence significantly elevates the cardiovascular disease risk, renal failure, and neuropathy [1-4]. This health crisis also places a tremendous economic burden on healthcare systems and reduces productivity, underscoring the urgent need for effective, sustainable interventions.

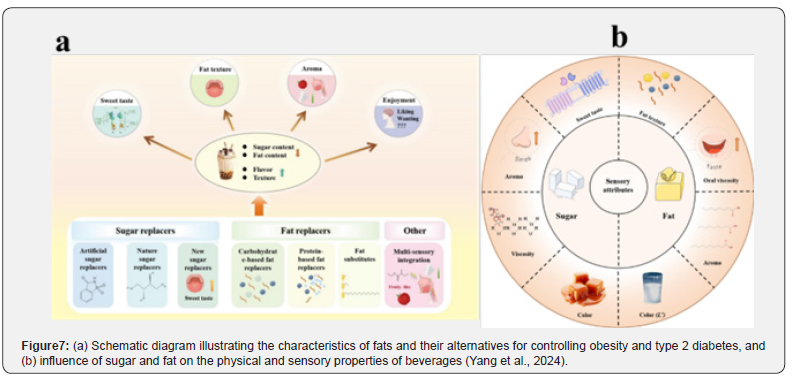

For decades, traditional health strategies have relied on universal dietary guidelines promoting low-calorie intake, reduction in saturated, trans, and total fat, and increased physical activity [5-7]. These messages have been simplified into slogans such as “eat less, move more” [8]. Although reducing these fats in products such as margarine, butter, and ice cream helped lower some metabolic risks, adherence to these guidelines has been challenging due to the desirable sensory properties of fats (e.g. melting point, texture, creaminess, aroma) [9-10]. However, the primary reason these guidelines have not been fully effective is the significant inter-individual variation in response to nutrients and dietary interventions [6]. For example, one individual may lose weight and improve insulin sensitivity on a low-fat diet, while others may experience little benefit or even adverse effects.

The rise in obesity and diabetes has been strongly associated with unhealthy dietary patterns characterised by excessive intake of saturated and trans fats, sugar, and sodium [1]. Mainstream dietary therapy has focused on restrictionbased strategies such as low-calorie, low-fat, and lowsodium diets [1]. While some individuals benefit from these approaches, many fail to adhere to them. For instance, low-fat foods may lead to higher intake of refined sugars, increasing glycemic responses in insulin-resistant individuals [11]. Additionally, standard low-calorie diets may be ineffective for individuals with genetic predispositions that favour efficient energy storage. Therefore, dietary effects may not depend solely on the type of diet, but on the individual’s unique biological system. This perspective has moved the focus from what to eat to why and for whom specific dietary strategies are effective [12].

Personalised nutrition (PN) represents a new paradigm that aims to alter dietary guidelines for individuals’ characteristics to prevent and manage chronic diseases incidence [13]. PN goes beyond genetic advice by integrating multiple layers of biological data, such as genetic structure, composition of gut microbiota, metabolism, and lifestyle factors [14]. Understanding the complex interplay between genes, resident microbes, and diet allows for more accurate predictions of dietary responses, making nutritional interventions more effective and sustainable. These strategies do not discard traditional healthy eating principles; rather, they optimise them for everyone. For example, PN evaluates which individuals benefit more from a low-fat versus lowsugar diet, or which types of dietary fibre can modulate the gut microbiome to improve glycaemic control [15].

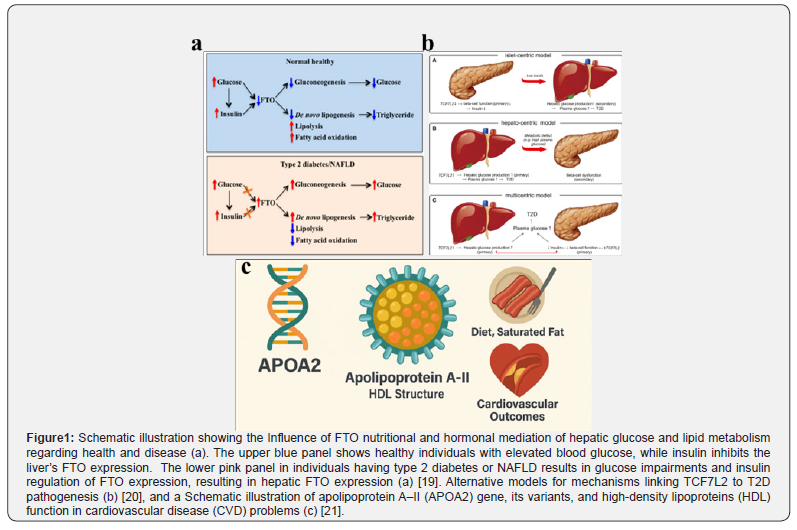

This review focuses on the scientific foundations of PN and the evidence showing how genetic variation influences nutrient responses, the central role of the gut microbiome as a metabolic interface and the dynamic interplay among these factors (Figure 1). It presents a framework for translating this evidence into practical diet therapy, as well as exploring future perspectives and challenges to help establish personalised nutrition as a mainstream approach for managing overweight, obesity, and diabetes.

The genetic blueprint and dietary response

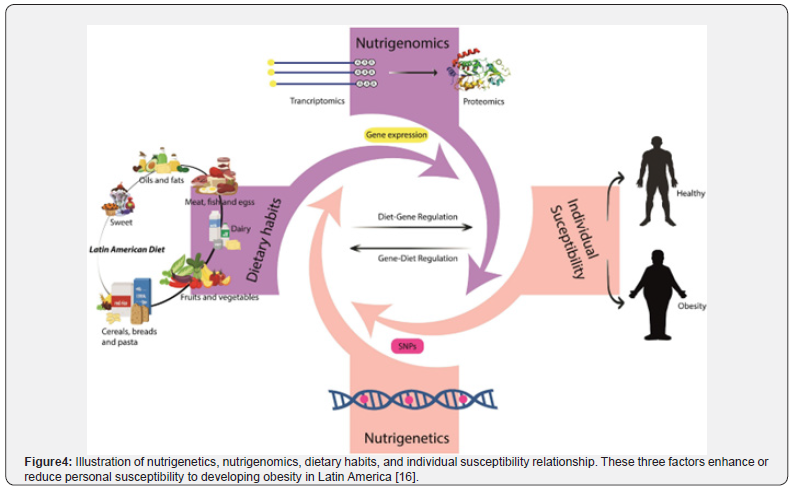

There is an increasing interest in understanding how genetic alterations influence the response to diet and nutrients [16]. Research has shown that genetic makeup plays a considerable role in metabolism, satiety signalling, and susceptibility to diet-related diseases [17]. Genetic polymorphisms-common variations in the DNA sequence –can alter protein function involved in digesting carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, and can affect appetite regulation and hormonal responses. Several key genes are related to metabolism and incidences of diseases, influencing obesity and diabetes, while others confer protective effects by improving insulin sensitivity or reducing the negative impact of saturated and trans-fat [18].

For example, the fat density and obesity-related genes, such as FTO, are considerably associated with the risk of obesity (Figure 1a). Individuals carrying the rs9939609 risk allele tend to consume more energy and have reduced satiety sensitivity [22]. This variation can impair the function of ghrelin, the hunger hormone, resulting in higher post-meal ghrelin levels and a reduced feeling of fullness. Additionally, the FTO risk allele is associated with a preference for high-calorie, high-fat foods, indicating that its effect on obesity is mediated more by appetite and food choices than by metabolism [18].

The transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCFF7L2) gene plays a crucial role in carbohydrate metabolism [20-23][51]. Variation in TCF7L2 significantly increases the risk of diabetes (Figure 1b). Individuals with high-risk variants may experience greater metabolic disturbance when consuming high-glycaemic foods, as their bodies are less able to secrete sufficient insulin, resulting insulin resistance and diabetes [24].

The Apolipoprotein A-II (APOA2) gene influences dietary fat response (Figure 1c) [25]. Individuals carrying the CC genotype at rs5082 exhibit a considerably higher body mass index (BMI) compared to those with the T-allele [26]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARy) causes major regulation of fat cell differentiation and lipid storage [27]. The common Ptro12Ala (rs1801282) polymorphism modulates its activity [28]. The Pro/Pro genotype is linked to higher insulin resistance and adverse response risk to high-fat diets, demonstrating the genetic modulation of dietary fat metabolism [29].

Differential responses to diet based on genetics are a key concept in nutrigenetics, which seeks to apply this knowledge to improve dietary interventions [6]. For example, low-fat diets may be highly effective for individuals with specific genotypes affecting lipid metabolism, such as APOA2 or PPARy [30]. In such a case, a low-fat diet can promote weight loss and reduce cardiovascular risk. Additionally, individuals with high-risk TCF7L2 variants may benefit from a low-fat, high-fibre diet to counteract impaired insulin secretion.

Low-sugar or low-carbohydrate diets may help individuals with satiety challenges or genetic risk factors involving TCF7L2 or FTO [22]. The Mediterranean diet, which is rich in unsaturated fats, fibre, and polyphenols, can mitigate genetic risk by enhancing satiety and reducing negative metabolic outcomes. Monounsaturated fats can minimise adverse effects in individuals with APOA2 or PPARy risk variants compared to saturated fats.

Genetic testing for personalised dietary advice is promising but must be implemented with an understanding of its strengths and limitations. Direct-to-consumer genetic tests can offer insights that support better dietary choices. For clinicians, genetic data can inform more precise dietary recommendations, leading to long-term outcomes and adherence. However, individuals’ genetic variants often contribute only a small portion of overall risk. Obesity and metabolic traits are polygenic, influenced by hundreds or thousands of genes [31]. Testing a few polymorphisms captures only a fraction of the variations in dietary response.

Moreover, genetics is not destiny. Non-genetic factors such as gut microbiota, sedentary behaviour, stress, physical activity, sleep, and overall dietary patterns play dominant roles [32]. There are also ethical and psychological considerations, as individuals may develop fatalistic attitudes or unnecessary anxiety after receiving genetic risk information. Current evidence suggests that genetic profiles are valuable but not sufficient as standalone tools for public health recommendations [33]. The most effective approach is to integrate genetic insights into a holistic framework that considers lifestyle, environmental health conditions, and personal preferences [34]. The future of personalised nutrition lies not in genetic determinism, but in using genetic information as one important component of a broader, individualised strategy.

The gut microbiome as a metabolic mediator

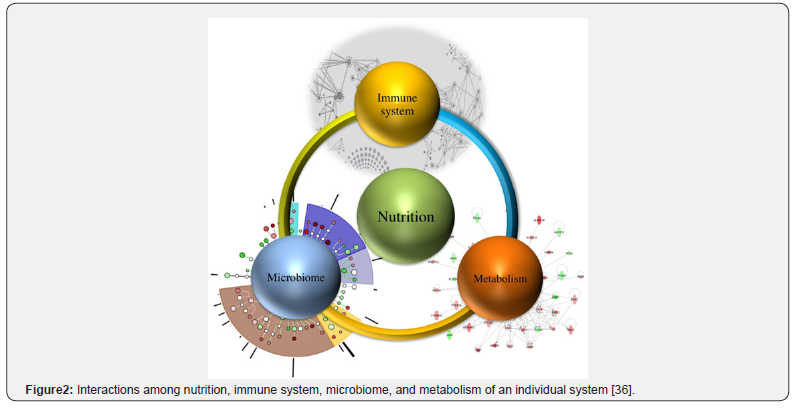

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a vast and complex community of microorganisms collectively known as the gut microbiome [6]. Often referred to as the “forgotten organ”, it consists of trillions of fungi, bacteria, viruses, and archaea, with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes being the most dominant phyla [6][35]. From being a passive bystander, the gut microbiome is a critical mediator of both health and disease (Figure 2). It contributes to the synthesis of essential compounds such as vitamin K and B, supports gut barrier integrity, and modulates the host immune system, which is particularly relevant to obesity and diabetes [6].

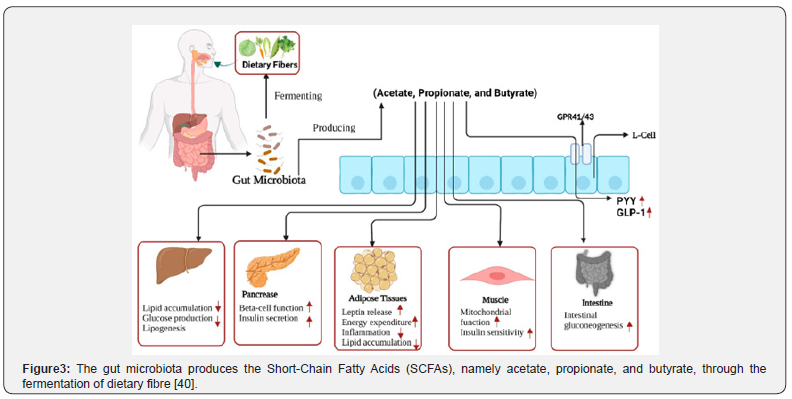

The gut microbiota influences host energy balance by enhancing the extraction of energy from indigestible dietary components, particularly nutritional fibres. Through fermentation, the microbiome converts fibres into Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCGAs) such as acetate, propionate and butyrate (Figure 3) [6][37]. These SCFAs serve as an energy source for colonocytes and exert systemic effects. They stimulate the release of gut peptides, including Peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which improve insulin sensitivity and promote satiety. However, an overly efficient microbiome may enhance calorie extraction, contributing to weight gain and obesity. Certain microbial patterns promote chronic low-grade inflammation, a hallmark of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Dysbiosis, often associated with a compromised gut barrier (“leaky gut”), facilitates the translocation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides into the bloodstream, triggering an inflammatory response and impairing insulin signalling in peripheral tissues [38].

Diet is one of the most powerful and rapid modulators of the intestinal microbiota. Dietary patterns shape the microbial community by determining the availability of substrates that support specific bacterial species. Diets rich in fibre from vegetables, fruits and legumes promote a healthy microbiota. These complex carbohydrates are fermented by saccharolytic bacteria, leading to the production of beneficial SCFAs and the growth of taxa such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobaeillus [37]. Dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet, which is high in fibre, are linked to greater microbial diversity and a more favourable metabolic profile. In contrast, Western-style diets high in saturated fats and refined sugars, low in fibre and composed largely of ultra-processed foods contribute to dysbiosis, reduced SCFA production, and decreased microbial diversity [6]. Therefore, diets rich in dietary fibre should be prioritised over unhealthy, high-fat foods. Researchers in food science should explore innovative strategies to replace highfat Western foods with low-fat, fibre-rich alternatives to help prevent and manage obesity and diabetes [4][39].

The critical interplay among genetics, microbiome, and diet

The complexity of metabolic health increases when considering the interactions among host genetics, the microbiome and diet. [41] These interactions may be synergistic, enhancing health outcomes, or antagonistic, where one factor counteracts the risk imposed by another. A well-known example is the metabolite TMAO, which has been associated with cardiovascular diseases [42]. TMAO is produced in two steps: first, gut microbes metabolise dietary nutrients such as those found in red meat and phosphatidylcholine into Trimethylamine (TMA); second, liver enzymes such as Flavin monooxygenases 3 convert TMA into TMAO [42]. This illustrates a multiplicative risk involving both microbial activities, demonstrating antagonistic interactions where one factor mitigates or exacerbates another.

In obesity, the interplay among host genes, the microbiome, and diet is particularly complex (Figure 2) [6]. For instance, individuals carrying FTO obesity risk alleles may have an increased tendency for energy intake and an enhanced ability to extract energy from dietary fibres, promoting weight gain [6][18]. Dietary interventions targeting these interactions are therefore essential. Prebiotic fibres that selectively promote the growth of SCA-producing bacteria, such as those that generate propionate, can improve satiety signalling and aid in weight management. Understanding these synergistic and antagonistic effects is an emerging frontier in food and nutritional science. Personalised dietary recommendations should consider not only genetic variation but also the unique microbial community of everyone, allowing for more precise and effective management of obesity and diabetes (Figure 4).

Science evidence into practice: A framework for personalised diet therapy

The compelling science of nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics is transitioning from laboratory research to clinical practice, moving from a simplistic one-gene-one-diet approach to a more sophisticated and multifaceted model for Personalised Nutrition (PN) diet therapy [43]. Consequently, the paradigm date to shifting toward leveraging advanced technologies and integrated data to engineer more dynamic, tailored dietary plans that can more effectively control and manage the incidence of chronic disease.

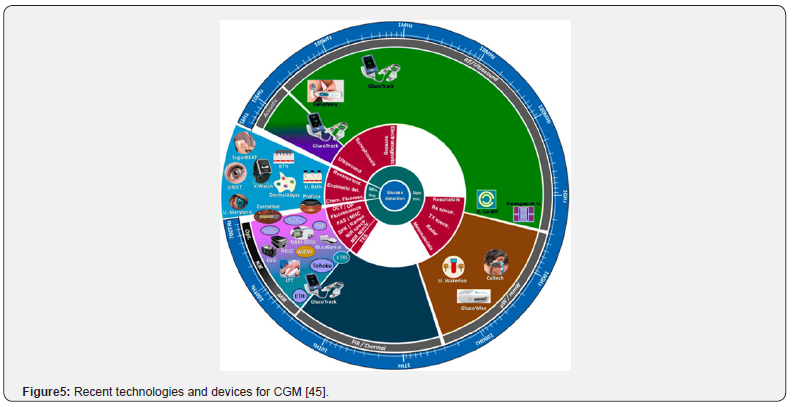

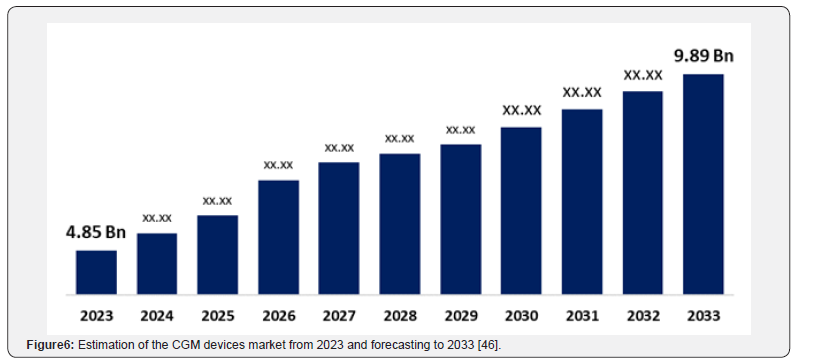

A model for integration has been proposed, involving a tiered system. Initially, a baseline investigation of genetics and the microbiome inform broad-stroke recommendations and identifies potential risks. This is followed by using data from continuous digital health monitoring tools, as their demand is increasing with time [43]. Devices like Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM), for instance, provide real-time data on an individual’s glycaemic responses to carbohydrate-based foods, highlighting the limitation of universal dietary guidelines (Figure 5) [44]. CGM utilisation increases annually (Figure 6), and its data helps personalise meal timing, food combinations, and portion sizes. Mobile applications and other electronic devices are essential for collating data from CGMs, tracking physical properties, and logging food intake [43-44].

However, certain issues must be considered and addressed before their widespread implementation in research and practice. These include cost, accessibility, data privacy, regulatory oversight, and the training of healthcare professionals. Future dietary therapies should be designed to intelligently integrate genetic, microbiota and metabolic data, facilitated through digital platforms. Addressing the associated ethical, economic, and educational challenges is crucial to ensure that personalised nutrition fulfils its potential to improve public health equitably and effectively.

Challenges, ethical considerations, and Future Perspectives

The promising field of PN is considered a critical juncture. The importance of revolutionising dietary therapy is vast. Additionally, the link from research to wide clinical applications is fraught with challenges that should be carefully addressed. These involve considerable research gaps and ethical implications, as well as a straightforward roadmap for future research and scientific inquiry.

Current challenges and research gaps

The main challenge is the significant research gaps that cause limitations in the immediate PN frameworks’ implementations. Most of the previous studies are short-term or homogenous populations, which could not capture the long-term effectiveness and broader level applicability of PN. There is an urgent need for larger, diverse and longitudinal population research that underscores the complex genetics, gut microbiome, lifestyle, and environmental changes with time [6]. To investigate the meal timings and composition, there is a need for future study to investigate how such foods influence on metabolism of the individual [45]. Additionally, the present landscape for consumer monitoring tests and digital health devices is disintegrated. Hence, oversight is important to understand the analytical validation, clinical utility, and ethical marketing of these technologies to protect consumers.

Ethical Implications

The promising field of PN is a critical point. The potential to revolutionise dietary therapy is substantial. However, applying research findings to widespread clinical applications is fraught with challenges that must be addressed. These include significant research gaps, ethical implications, and the need for a clear roadmap for future scientific inquiry.

One of the main challenges in PN is the presence of substantial research gaps, which limit the immediate implementation of PN frameworks. Several previous studies have been short-term or conducted in homogeneous populations, which fail to capture the long-term effectiveness and broader applicability of PN. The large-scale, diverse, and longitudinal population research that considers the complex interactions of genetics, the gut microbiome, lifestyle, and environmental factors over time.

Furthermore, future studies are needed to investigate meal timing and composition, particularly how specific foods influence metabolism across the entire population, including children, adolescents and the elderly. The current landscape of consumer monitoring tests and digital health devices is fragmented. Therefore, stronger oversight is essential to ensure analytical validation, clinical utility, and ethical marketing of these technologies to protect consumers.

The application of PN raises several ethical concerns that must be carefully managed. The use of genetic and other sensitive health data poses significant risks to data privacy and security. From a psychological perspective, PN could contribute to nutritional nihilism, where individuals develop fatalistic attitudes, believing that their genetic health inequalities if advanced PN therapies remain accessible only to privileged populations, thereby widening socioeconomic health disparities. Ensuring equitable access to these advanced dietary strategies is an ethical imperative for students, researchers, clinicians, and policymakers alike.

Further research should aim to overcome current limitations and unlock the full potential of PN. The following areas warrant specific attention.

Low–fat and low-carbohydrate foods

Many obese and diabetic individuals require low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets or foods. Further research is needed to examine dietary patterns in relation to specific genetic variants [7][47].

For example, individuals with APOA2 polymorphisms or specific gut microbiome compositions may experience superior weight management and improved fatty acid metabolism when consuming low-fat diets. Tailoring dietary advice based on genetic and microbial profiles may enhance health outcomes.

Low-calorie diets for long-term success

Although caloric restriction is a cornerstone of weight management, long-term outcomes are often poor due to metabolic adaptations that promote weight regain [7][48]. Further research should explore personalised supplementation, particularly plant-based diets and encapsulation of healthy macronutrients within calorie-restricted regimes. Such strategies may improve adherence, preserve muscle mass, and mitigate metabolic slowdown in individuals with obesity and diabetes (Figures 7a and b) [49].

Utilisation of low sugar and natural sweeteners

To reduce sugar intake in obese and diabetic patients, there is a growing need for effective sweetener alternatives (Figure 7a). Research should focus on individual variations in taste, texture, and aroma perception when using natural sweeteners that are compatible with host metabolism and gut microbiota [7]. This could support the development of PN-based sugar and calorie reduction strategies, resulting in more effective and sustainable dietary therapies with significant health benefits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Personalised Nutrition (PN) represents a transformative shift from traditional “one-size-fits-all” dietary recommendations toward a more individualised and evidence-based approach to health. Rather than focusing solely on what to eat, PN emphasises why and for whom specific dietary strategies are most effective. By integrating genetic information, such as variation in genes like FTO. TCF7L2 and APOA2, with data on gut microbiota composition and metabolic responses, PN enables the development of more precise and effective nutritional interventions.

The complex interplay between host genetics, gut microbiota, and environmental factors determines individual variability in nutrient metabolism, energy balance, and disease risk. Therefore, PN has the potential to significantly improve the prevention and management of metabolic disorders, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

To translate PN from a promising concept into practical healthcare, several challenges must be addressed-such as conducting long-term, population-diverse studies, ensuring ethical data use, lowering implementation costs, and developing professional training frameworks. Future research should focus on refining dietary recommendations for specific genetic and microbial profiles, promoting long-term sustainable and optimising energy and carbohydrate intake through natural and functional food ingredients.

Ultimately, PN does not reject the foundational principles of healthy eating but rather enhances and personalises them. This approach offers a path toward more effective, sustainable, and individualised management of metabolic health, reducing the growing personal and societal burden of obesity, diabetes, and related disorders.

CRediT authorship Contribution Statement

Ponam Saba: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing of the initial draft, Funding acquisition. Shahid Iqbal: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualisation, Methodology, Supervision, validation, Funding acquisition. Rizwan Ahmed Bhutto: Visualisation, suggestion. Zhixiao Ye: Validation, Visualisation. I-Jun Chen: Writing, review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Project administration..

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that they have no known competing financial interests to declare.

References

- Edwards T (2025) APOA2 gene variants and cardiovascular disease risk, Revolution Health & Wellness 1008 West Taft Ave Sapulpa OK74066 USA.

- Witka BZ, Oktaviani DJ, Marcellino M, Barliana MI, Abdulah R (2019) Type 2 Diabetes-Associated Genetic Polymorphisms as Potential Disease Predictors. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 12: 2689

- Duan Y, Zeng L, Zheng C, Song B, Li F, et al. (2018) Inflammatory Links Between High Fat Diets and Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 9: 424482.

- Tang Z, Yang S, Li W, Chang J (2025) Fat Replacers in Frozen Desserts: Functions, Challenges, and Strategies. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 24(3): e70191.