Abstract

Background: Dietary intervention is the primary means of preventing the occurrence of sepsis. However, there is insufficient existing evidence regarding the impact of specific foods on sepsis.

Methods: We employed two-sample Mendelian randomization and multivariable Mendelian randomization for genetic prediction, analyzing the impact of 31 dietary intake items, Including the 23 individual dietary intakes and 8 dietary habits, on the risk of septicemia and its subtypes. Weighted median, MR-Egger, and inverse variance weighting were used as the primary methods for Mendelian randomization analysis. Heterogeneity and pleiotropy analyses were conducted to ensure the accuracy of the results.

Results: The intake of cheese (OR=0.63, p<0.05) and dried fruits (OR=0.57, p<0.05) is positively correlated with a significant reduction in the risk of common sepsis, while completely avoiding wheat products can lead to a substantial increase in the risk of common sepsis (OR=29.41, P=0.004). In the subtype analysis of sepsis, it was found that an increase in the weekly intake of red wine raises the risk of streptococcal sepsis (OR=8.09, p=0.048), while regular tea drinking has a certain protective effect against sepsis.

Conclusion: The study demonstrates that cheese and dried fruit consumption significantly reduce sepsis risk, while wheat avoidance markedly increases sepsis risks. Additionally, red wine intake increases the risk of streptococcal sepsis.

Keywords:Sepsis; Postpartum infection; Streptococcal infection; Dietary factors; Mendelian randomization

Introductıon

The definition of sepsis is an immune system disorder caused by infection [1-3], which can progress to life-threatening conditions. With the rapid development of intensive care technology, the incidence and mortality rates of sepsis have shown a significant downward trend. However, the global incidence of new cases of sepsis remains high, with related deaths accounting for 19.7% of global mortality [4], still making it a major factor in the global disease burden.

Some dietary and lifestyle habits may affect the incidence of sepsis. Therefore, understanding whether dietary changes are beneficial to the incidence of sepsis is of significant importance. It has been observed that dietary behavior patterns are heritable. Genome-wide Association Studies (GWAS) have identified genetic variations associated with various dietary traits. These findings provide an opportunity to use genetics within a Mendelian Randomization (MR) framework to better understand the relationship between dietary exposure and susceptibility to sepsis. MR utilizes genetic variations related to exposure (e.g., dietary habits) as Instrumental Variables (IV) to estimate the causal impact of that exposure on outcomes (the risk of sepsis and its subtypes). Therefore, MR can be used to provide supporting evidence for the causal effect of exposure on outcomes.

In this study, we conducted a univariate MR analysis to test the analysis of 31 dietary intake exposure lists, which included 23 individual dietary intakes and 8 dietary habits. Different dietary components and habits showed a significant dose-response relationship with the occurrence and development of sepsis. Causal evidence supporting the dietary components’ effect on sepsis was identified. It is widely believed that understanding the impact of dietary intake on the risk of sepsis incidence can enhance the prevention of sepsis. Therefore, our aim is to assess whether diet is associated with the risk of sepsis when using genetic instruments for instrumental variable analysis.

Methods and Material

Methods

The GWAS summary-level data used in this study were released by the IEU Open GWAS project. GWAS data from the UK Biobank, previously published GWAS datasets, and the FinnGen biobank were collected, curated, and analyzed. Because these data are publicly available and de-identified, this study is exempt from ethics review.

Material

The exposure data come from the GWAS of the UK Biobank and include a list of 31 dietary intake items, comprising 23 individual dietary intakes and 8 dietary habits. The 23 individual dietary intakes are bacon, beef, bread, cereals, cheese, coffee, cooked vegetables, dried fruits, fresh fruits, lamb, milk, non-oily fish, oily fish, pork, poultry, processed meats, raw vegetables, salted nuts, salted peanuts, tea, unsalted nuts, unsalted peanuts, and yogurt. The 8 dietary habits include average weekly beer intake, average weekly red wine intake, average weekly spirits intake, never consuming dairy products, never consuming eggs or egg-containing foods, never consuming sugar or sugary foods and drinks, never consuming wheat products, and regular consumption of eggs, dairy products, wheat, and sugar. The outcome data come from the FinnGen consortium and include sepsis (ieu-b-4980), postpartum sepsis (finn-b-O15_PUERP_SEPSIS), and streptococcal sepsis (finn-b-AB1_STREPTO_SEPSIS) (Table 1).

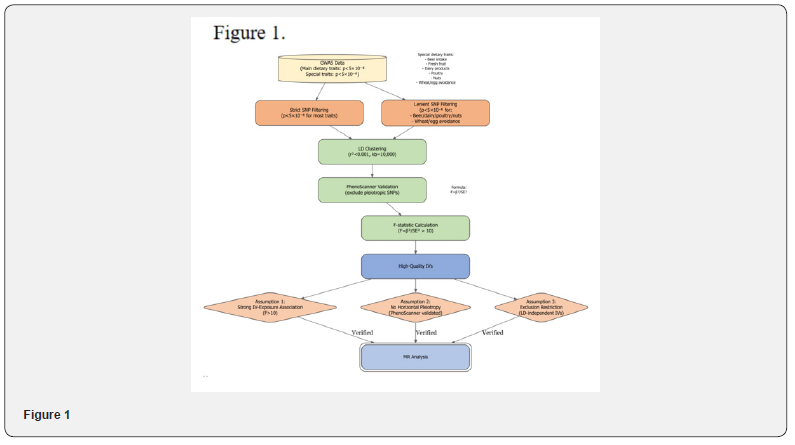

Instrumental Variable Selection

Instrumental variable selection criteria: We screened SNPs related to diet and sepsis and its subtypes, using a strict threshold from Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) (p<5×10⁻⁸) for related SNPs; for exposure factors with limited data such as beer intake and fresh fruit intake, the threshold was relaxed to p<5×10⁻⁶. Highly correlated SNPs were removed using Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) clustering method (R2 < 0.001, clustering window > 10,000 kb), while SNPs associated with outcomes were excluded through the PhenoScanner database. Finally, the F statistic was calculated based on the formula F=beta²/se², retaining only SNPs with F>10 to exclude weak instrumental variable bias, ensuring the robustness and reliability of the MR analysis (Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

To study causal relationships, we employed five MR methods: Inverse Variance Weighting (IVW), MR-Egger regression, weighted median, weighted model, and simple mode. In MR analysis, IVW is considered the most reliable method for determining causal relationships and is the primary method used for estimating causal relationships. The variability within the Inverse Variance Weighting (IVW) model was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test. A p-value of less than 0.05, from Cochran’s Q test, indicates the presence of heterogeneity. However, detecting heterogeneity does not necessarily undermine the validity of the IVW model. To address potential directional pleiotropy, the MR-Egger approach, which allows for a non-zero intercept, was employed. Additionally, a leaveone- out analysis was conducted to assess whether excluding any individual Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) significantly affected the results. We used the MR-PRESSO method to detect outliers. Once outliers were identified, they were immediately removed. After removing outliers, MR analysis was performed again. All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.2) using the TwoSampleMR package.

Results

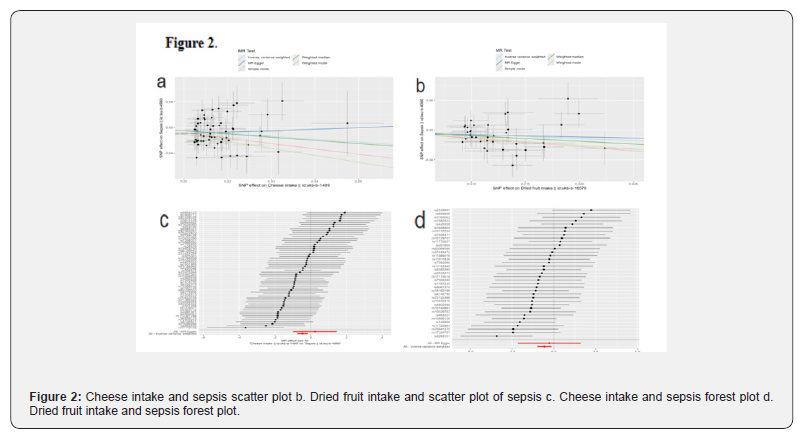

The analysis utilizing Inverse Variance Weighting (IVW) indicated a significant inverse association between cheese consumption and the likelihood of developing sepsis, with an Odds Ratio (OR) of 0.63 (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.47-0.86, P=0.0029). Furthermore, the outcomes derived from the weighted median approach corroborated these findings, presenting an OR of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.41-0.90, P=0.0133). Dried fruit intake also showed a protective effect (IVW OR=0.57, 95%CI:0.37-0.87, P=0.0096). Tea intake was not significantly associated with the risk of sepsis (P=0.0585).

Diet and puerperal sepsis

The intake of oily fish is not significantly associated with the risk of puerperal sepsis (IVW OR=1.82, 95%CI:0.94-3.54, P=0.0766). The intake of red wine shows a potential protective trend, but does not reach statistical significance (IVW OR=0.26, 95%CI:0.06-1.10, P=0.0671) (Figure 2).

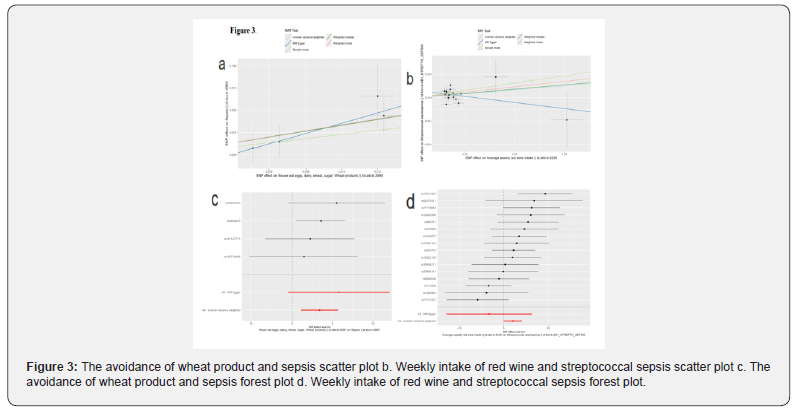

Diet and Streptococcal Sepsis

Completely avoiding wheat products can significantly increase the risk of ordinary sepsis (OR=29.41, P=0.004). In the subtype analysis of sepsis, it was found that an increase in weekly red wine intake raises the risk of streptococcal sepsis (OR=8.09, p=0.048) (Figure 3).

The forest plot assessed the causal associations between four dietary factors (avoiding wheat products, cheese intake, dried fruit intake, red wine intake) and the risk of sepsis through Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis, and the results showed:

Figure 4 Avoiding the causal association between the intake of wheat products, cheese, dried fruits, and red wine with the risk of sepsis.

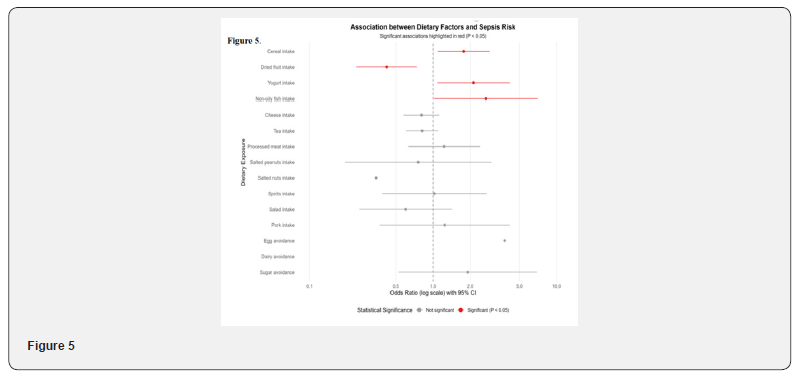

Multivariable Mendelian randomization analysis: Causal association between dietary factors and the risk of sepsis.

Grain intake is significantly positively correlated with the risk of sepsis (OR=1.7669, 95% CI 1.0900–2.8641, P=0.0209); dried fruit intake shows a significant protective effect (OR=0.4211, 95% CI 0.2397–0.7398, P=0.0026); yogurt intake is associated with an increased risk of sepsis (OR=2.1246, 95% CI 1.0785–4.1857, P=0.0294); non-oily fish intake has a potential positive association (OR=2.6773, 95% CI 1.0187–7.0364, P=0.0458) (Figure 5).

Dried fruit intake: OR < 1, indicating a protective effect. Yogurt intake: OR < 1, possibly related to probiotics improving intestinal barrier function. Non-oily fish intake: OR < 1, rich in high-quality protein and anti-inflammatory components. Processed meat intake: OR > 1, possibly related to pro-inflammatory components such as high salt and nitrites. Spirits intake: OR > 1, excessive alcohol may impair immune regulation.

Discussion

Currently, some studies indicate that certain lifestyle factors are closely related to the susceptibility and prognosis of sepsis, but there is a lack of large-sample randomized controlled studies on whether there is a causal relationship between factors such as diet and alcohol consumption and sepsis [5]. We conducted a replication of the Mendelian Randomization (MR) analysis, employing the latest findings derived from the Inverse Variance Weighted (IVW) model to assess the presence of a causal link. The consumption of cheese exhibited a significant inverse association with the likelihood of developing sepsis (Odds Ratio [OR]=0.63, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.47-0.86, P=0.0029). Furthermore, the outcomes obtained from the weighted median approach corroborated these findings (OR=0.61, 95% CI: 0.41-0.90, P=0.0133). Dried fruit intake also showed a protective effect (IVW OR=0.57, 95%CI:0.37-0.87, P=0.0096). This suggests the existence of a causal link; consequently, we contend that the effectiveness of the 95% confidence interval and the p-value associated with the critical value is constrained. While it is acknowledged that numerous Mendelian Randomization (MR) studies concentrate on identifying risk or protective factors related to sepsis, there is a notable lack of research addressing the influence of dietary components, specifically fruit and vegetable consumption [6]. To date, sepsis remains one of the most challenging emergency critical illnesses in the field of intensive care medicine, and the medical costs are enormous [7]. In recent years, with advancements in clinical technology and basic research, the mortality rate of sepsis has significantly decreased over the past few decades, but due to its pathogenesis and complex pathophysiological processes, which involve dysregulation of the immune system and interactions between microorganisms, providing proactive and effective preventive measures is extremely important [8-10]. To our knowledge, many studies focus on how lifestyle factors affect the human immune system, thereby influencing the occurrence and development of sepsis.

Research results show that the consumption of cheese has a significant causal relationship with the risk of sepsis, possibly because its fermentation process contains calcium, vitamin K2, and Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) that play a coordinated role in jointly regulating immunity, promoting the production of anti-inflammatory cells, and inhibiting the production of tumor necrosis factors [11-13]. However, the genetic polymorphism in the European population may derive more benefits from dairy products, especially cheese [14-15], while Asians have a genetic predisposition to poor lactose tolerance, but still experience some benefits, albeit relatively fewer [16]. Nuts, such as cashews and walnuts are rich in dietary fiber and various trace elements, and the interaction of these components can regulate gut microbiota, modulate the body’s immunity, and reduce cellular damage. The abundant trace elements can maintain the function of immune cells, such as T cell function [17-18]. In addition, nuts also contain a large number of polyphenolic substances, which can scavenge oxygen free radicals and alleviate cellular and bodily stress responses [19].

Streptococcus is a normal flora in the oral cavity and nasopharynx, generally non-pathogenic. When the body’s resistance decreases, it can cause lobar pneumonia or bronchitis, and can enter the cerebrospinal fluid through the blood-brain barrier, leading to purulent meningitis and sepsis [20-22]. The alcohol component in red wine can suppress the immune function of the body [23], and there are significant individual differences in alcohol metabolism, especially since red wine contains tannic acid, which can promote the biofilm of Streptococcus and increase its pathogenicity [24]. However, during the MR analysis, it was found that the intake of red wine during the puerperium showed a potential protective trend, but did not reach statistical significance (IVW OR=0.26, 95%CI:0.06-1.10, P=0.0671). Because women need to quickly enhance their immune function at this time, the sample size of the study subjects is relatively small. Particularly when exploring the complex relationship between alcohol consumption and health, one should be cautious in drawing conclusions based on a small sample size.

Wheat products and grains are rich in dietary fiber, unsaturated fatty acids, proteins, and other nutrients, which have functions such as preventing and improving chronic diseases, regulating immunity, and providing antioxidant effects [25-27]. High dietary fiber intake in the diet of the population interacts with the microbiota in the gut, promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria, inhibiting the reproduction of harmful bacteria, regulating the composition of gut microbiota, maintaining the dynamic balance of gut microbial communities, and promoting human health [28- 30]. Under the influence of gut microbiota, a significant amount of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) can be produced, indicating that dietary fiber has a good synergistic regulatory effect on gut microbiota [31-32]. SCFAs can also provide nutrients for intestinal epithelial cells, promote the growth of intestinal mucosa, maintain the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier, further improve intestinal function, and promote overall health [33-35].

Conclusion

We used the TSMR method to study several dietary factors associated with the risk of sepsis. The intake of cheese and dried fruits showed a preventive effect on the risk of sepsis onset. In contrast, red wine and the non-consumption of wheat products are risk factors for sepsis susceptibility. These findings are consistent with some existing observational studies. This research can provide evidence to support existing clinical studies regarding the impact of dietary factors lacking strict condition control on the incidence of sepsis, and offer valuable insights for the development of nutritional strategies for patients susceptible to sepsis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y., B.Y. and Z.T.;

Methodology, Z.Y., J.H. and Y.P.;

Formal analysis, Z.Y. and L.S.;

Investigation, Z.Y. and J.X.;

Resources, B.Y.;

Data curation, L.S.;

Writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.;

Writing—review & editing, Z.T. and B.Y.;

Visualization, Y.P.;

Supervision, Z.T.;

Project administration, B.Y.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, as all analyses in this study were conducted using published summary statistics from genome-wide association studies.

Informed Consent Form

Not applicable, as all analyses in this study were conducted using published summary statistics from genome-wide association studies.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed can be obtained from the relevant research groups publicly.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation, grant number 2025GXNSFAA069457, and the Guangxi Clinical Research Center for Critical Care Medicine.

References

- van der Poll T, Shankar-Hari M, Wiersinga WJ (2021) The immunology of sepsis. Immunity 54(11): 2450-2464.

- Sheats MK (2019) A comparative review of equine SIRS, sepsis, and neutrophils. Front Vet Sci 6: 69.

- Deinhardt-Emmer S, Chousterman BG, Schefold JC, Flohne SB, Skirecki T, et al. (2025) Sepsis in patients who are immunocompromised: Diagnostic challenges and future therapies. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 13(7): 623-637.

- Via LL, Sangiorgio G, Stefani S, Marino A, Nunnari G, et al. (2024) The global burden of sepsis and septic shock. Epidemiologia 5(3): 456-478.

- Liao J, Jiang L, Qin Y, Hu J, Tang Z (2024) Genetic prediction of causal relationships between osteoporosis and sepsis: Evidence from Mendelian randomization with two-sample designs. Shock 62(5): 628-632.

- Helling H, Stephan B, Pindur G (2015) Coagulation and complement system in critically ill patients. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 61(2): 185-193.

- Luhr R, Cao Y, Söderquist B, Cajander S (2019) Trends in sepsis mortality over time in randomised sepsis trials: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of mortality in the control arm, 2002-2016. Critical Care 23(1): 241.

- Dong R, Liu W, Weng L, Yin P, Peng J, et al. (2023) Temporal trends of sepsis-related mortality in China, 2006-2020: A population-based study. Ann Intensive Care 13(1): 71.

- Liu Z, Ting Y, Li M, Li Y, Tan Y, et al. (2024) From immune dysregulation to organ dysfunction: Understanding the enigma of sepsis. Front Microbiol 15: 1415274.

- Falahatzadeh M, Najafi K, Bashti K (2024) From tradition to science: Possible mechanisms of ghee in supporting bone and joint health. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 175: 106902.

- Tvrzická E, Vecka M, Zák A (2007) [Conjugated linoleic acid--the dietary supplement in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases].Čas Lék Česk 146(5): 459-465.

- Su X, Yang Y, Gao Y, Wang J, Hao Y, et al. (2024) Gut microbiota CLA and IL-35 induction in macrophages through Gαq/11-mediated STAT1/4 pathway: An animal-based study. Gut Microbes 16(1): 2437253.

- Yang Y, Wang X, Yang W (2025) Biomarker assessment of cheese intake and stroke risk: A Mendelian randomization study. J Dairy Sci.

- Jacques N, Mallet S, Laaghouiti F, Tinsley CR, Casaregola S (2017) Specific populations of the yeast Geotrichum candidum revealed by molecular typing. Yeast 34(4): 165-178.

- Fardellone P, Séjourné A, Blain H, Cortet B, Thomas T (2017) Osteoporosis: Is milk a kindness or a curse? Joint Bone Spine 84(3): 275-281.

- Maggini S, Wintergerst ES, Beveridge S, Hornig DH (2007) Selected vitamins and trace elements support immune function by strengthening epithelial barriers and cellular and humoral immune responses. Br J Nutr 98(Suppl 1): S29-S35.

- Ströhle A, Wolters M, Hahn A (2011) Micronutrients at the interface between inflammation and infection--ascorbic acid and calciferol: Part 1, general overview with a focus on ascorbic acid. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 10(1): 54-63.

- Ullah H, Khan H (2018) Anti-Parkinson potential of silymarin: Mechanistic insight and therapeutic standing. Front Pharmacol 9: 422.

- Hermans PW, Sluijter M, Belkum VA (2001) Restriction fragment end labeling analysis: High-resolution genomic typing of Streptococcus pneumoniae Isolates. Methods Mol Med 48: 169-179.

- Quan Y, Wang Y, Gao S, Yuan S, Song S, et al. (2025) Breaking the fortress: A mechanistic review of meningitis-causing bacteria breaching tactics in blood brain barrier. Cell Communication and Signaling 23(1): 235.

- Coureuil M, Lécuyer H, Bourdoulous S, Nassif X (2017) A journey into the brain: Insight into how bacterial pathogens cross blood-brain barriers. Nat Rev Microbiol 15(3): 149-159.

- Watzl B, Bub A, Briviba K, Rechkemmer G (2002) Acute intake of moderate amounts of red wine or alcohol has no effect on the immune system of healthy men. Eur J Nutr 41(6): 264-270.

- Xu M, Wang X, Gong T, Yang Z, Ma Q, et al. (2025) Glucosyltransferase activity-based screening identifies tannic acid as an inhibitor of Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Front Microbio 16: 1555497.

- Alemayehu GF, Forsido SF, Tola YB, Amare E (2023) Nutritional and phytochemical composition and associated health benefits of oat (Avena sativa) grains and oat-based fermented food products. ScientificWorldJournal 2023: 2730175.

- Lahouar L, Ghrairi F, El Arem A, Medimagh S, Felah ME, et al. (2017) Biochemical composition and nutritional evaluation of barley Rihane (Hordeum vulgare L.). Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 14(1): 310-317.

- Kowalska H, Kowalska J, Ignaczak A, Masiraz E, Domain E, et al. (2021) Development of a High-Fibre multigrain bar technology with the addition of curly kale. Molecules 26(13): 3939.

- Huang H, Chen J, Hu X, Chen Y, Xie J, et al. (2022) Elucidation of the interaction effect between dietary fiber and bound polyphenol components on the anti-hyperglycemic activity of tea residue dietary fiber. Food & Function 13(5): 2710-2728.

- Mo Z, Zhan M, Yang X, Xie P, Xiao J, et al. (2024) Fermented dietary fiber from soy sauce residue exerts antidiabetic effects through regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and gut microbiota-SCFAs-GPRs axis in type 2 diabetic mellitus mice. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 270(Pt 2): 132251.

- Okouchi R, E S, Yamamoto K, Ota T, Seki K, et al. (2019) Simultaneous intake of Euglena gracilis and vegetables exerts synergistic anti-obesity and anti-inflammatory effects by modulating the gut microbiota in diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients 11(1): 204.

- Sembries S, Dongowski G, Jacobasch G, Mehrländer K, Will F, et al. (2003) Effects of dietary fibre-rich juice colloids from apple pomace extraction juices on intestinal fermentation products and microbiota in rats. Br J Nutr 90(3): 607-615.

- Borowicki A, Stein K, Scharlau D, Scheu K, Brenner-Weiss G, et al. (2010) Fermented wheat aleurone inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in human HT29 colon adenocarcinoma cells. Br J Nutr 103(3): 360-369.

- Bugaut M (1987) Occurrence, absorption and metabolism of short chain fatty acids in the digestive tract of mammals. Comp Biochem Physiol B 86(3): 439-472.

- Martin-Gallausiaux C, Marinelli L, Blottière HM, Larraufie P, Lapaque N (2021) SCFA: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc Nutr Soc 80(1): 37-49.

- D'Argenio G, Mazzacca G (1999) Short-chain fatty acid in the human colon. Relation to inflammatory bowel diseases and colon cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 472: 149-158.

- Spence C (2017) Comfort food: A review. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 9: 105-109.