Traditional Fermented Foods in Vietnamese Diet: A Potential Source of Probiotics

Vuong Bao Thy, Mai Nguyet Thu Hong, Tran Thi Hanh, and Jamuna Prakash*

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cuu Long, Vinh Long 85000, Vietnam

Submission: October 05, 2023; Published: October 18, 2023

*Corresponding author: Jamuna Prakash, Nutrition Advisor, University of Cuu Long, Vinh Long 85000, Vietnam. Email: jampr55@hotmail.com

How to cite this article: Vuong Bao T, Mai Nguyet Thu H, Tran Thi H, Jamuna P. Traditional Fermented Foods in Vietnamese Diet: A Potential Source of Probiotics. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2023. 12(4):555841. DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2023.12.555841.

Abstract

In recent times, consumers have become more interested in the role of food in health promotion and longevity, as well as in regulating various physiological functions and for prevention of non-contagious chronic diseases. Traditional foods are a means of transporting probiotics and nutraceuticals. Traditional probiotic-based foods can have positive effects on the composition of the gut microbiome and overall health. A growing demand for traditional foods stems from the ease of adaptability of these products to consumers and their potential as carriers of nutraceuticals and probiotics. Vietnam has a long history of traditional fermented products containing a variety of microorganisms with favorable technological, preservative, and organoleptic properties for food processing as well as other functional properties. This review highlights Vietnam’s most popular traditional fermented foods and their beneficial indigenous bacteria that promote health.

Keywords:Traditional fermented foods; lactic acid bacteria (LAB); probiotics; beneficial bacteria; health effect.

Abbreviations:WLAB: Lactic Acid Bacteria; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Introduction

The marketing trends over the past decade reveal that the present-day consumers have become more concerned about personal health and increasingly expect the food they consume to have health benefits. As the field of fermented foods and nutraceuticals gains attention, it is necessary to provide an overview of the positive effects the processed products can offer for human health. Probiotics, which make up a significant proportion of the fermented foods consumed by humans, seem to play a central role in this context. They show versatility in terms of both technological and nutritional aspects. In addition to meeting nutritional needs, fermented foods also contribute towards prevention of certain diseases [1,2].

Vietnam, situated in Southeast Asia, is a tropical country with a long history of producing traditional fermented products. Unlike Western countries where commercially fermented foods are produced on a large scale using industrially produced starter yeasts, in Vietnam these foods are home-based or on small-scale production passed down through generations. Most of Vietnam's traditional fermented products are handcrafted and closely related to the local natural microbiome. This makes these foods a good source of beneficial native microorganisms. This review is an attempt to capture information on traditional Vietnamese fermented foods to provide a comprehensive overview of their functional properties.

Fermented Foods

Indigenous or traditional fermented foods are part of a particular culture because they are intimately linked to the lives of the local people. The fermentation processes used in the production of these indigenous fermented foods are often completely based on the natural microbiome of the raw materials and the surrounding environment; and procedures are passed down from generation to generation as a process of inheritance. Because traditional food fermentation industries are often home-based and rely heavily on indigenous ingredients without the benefit of using commercial starter cultures, micro-assemblies of organisms are unique and highly variable for each product and each region. Thus, the possibility of discovery of new organisms, products and interactions is possible [3].

Initially, fermented foods were prepared by hand and without any knowledge of the role of microorganisms involved. But in the mid-19th century, a change in the way food fermentation was done and the understanding of the process was witnessed. Since then, technologies baes on science for the industrial production of fermented dairy products, meat, fruits, vegetables, and grains have been developed all over the world. Fermentation brings about biochemical changes in foods due to microbial or enzymatic action resulting in improved taste, texture, odor, and antioxidants profile. There are more than 4000 traditional fermented foods and beverages in the world prepared and consumed by billions of people of different ethnicities and communities.

Various microorganisms, especially of the genus lactic acid bacteria (LAB), are involved in common food fermentation processes. They not only contribute to the flavor of food, but also can inhibit pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms through a variety of ways including production of peroxidase, organic acids and bacteriocins. Several decades ago, the identification of the microbiome in food was mainly dependent on culture methods; and the properties of each isolate were evaluated under controlled conditions. However, with the advent of molecular techniques, enumeration of missed microorganisms by culture-dependent methods is now possible. In addition, as more bacterial-specific metabolites, such as bacteriocins, are being reported, a broader database is now available for identification and comparison with potential new products [3].

Traditional Fermented Foods

Traditional foods, whether of plant or animal origin, are a complex part of the diets of people in all parts of the world. It is the variety of raw materials used as the substrate, the method of preparation and the organoleptic quality of the finished product that is astounding as one begins to learn more about the eating habits of different cultures. Traditional foods are usually prepared by fermenting raw materials using the natural microflora present on the raw materials or in the environment, with or without the addition of starter yeast. As LABs isolated from fermented foods are becoming globally important for human probiotic use, the new isolates could pave the way for intense research in medical applications. Furthermore, a large proportion of fermented foods have not been discovered in terms of their microbiome, thus they may be exploited in the future to isolate beneficial probiotic strains with specific characteristics. Fermented foods are classified into (i) fermented plant foods, (ii) fermented cereal foods, (iii) fermented meat foods, (iv) fermented dairy foods, (v) fermented beans and (vi) other fermented foods.

Benefits of Traditional Foods rich in Probiotics

One notable aspect of traditional foods is that they have a biological function that enhances some of the health-promoting benefits for consumers due to the functional microorganisms associated with them [4]. In addition to the usual role of these functional microorganisms in acid, flavor, and texture development, they are also considered to be the evolving ‘cell factory’ [5] to produce host of functional biomolecules and food ingredients such as bio thickeners, bacteriocins, vitamins, bioactive peptides, and amino acids. Scientists demonstrated that in addition to the technological properties (sugar substitutes, fillers, texturizers, humectants, cryoprotectants) of low-calorie sweeteners produced from LAB, they have also been observed to have several health benefits (low calorie, low glycemic index, anticancer, osmotic diuretic, obesity control, prebiotic) [6]. Furthermore, traditional probiotic-rich foods are receiving a lot of attention for their claimed health benefits including improved lactose tolerance, increased natural resistance to infectious disease, etc. in the gastrointestinal tract, inhibiting cancer, antidiabetic, lowering serum cholesterol levels and improving digestion [1,2].

Health Benefits of Probiotics

The human gut contains tens of trillions of bacteria in thousands of different species. Scientists call this community of organisms living in the gut microbiome, microbiota. Most gut bacteria are not harmful, some are beneficial, and some cause disease in humans [7]. The human digestive system has about 400 types of probiotics. These are beneficial microorganisms, bacteria and yeasts that live mainly in the large intestine, helping to naturally balance the intestinal microflora. Two groups of probiotics that have been used therapeutically are Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, specifically Lactobacillus acidophilus, found in yogurt [7].

Scientific evidence indicate that probiotics help the body by strengthening the immune system, preventing infections and harmful bacteria in the digestive system, preventing, or eliminating toxins caused by certain bacteria, maintaining healthy skin and nerves and for anti-aging properties [8,9]. In clinical practice, probiotics are used in combination for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), diarrhea, and constipation. Probiotics have also been shown to be useful in the treatment of obesity, diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [9,10].

However, probiotics have also been associated with few harmful side effects: (i) digestive disorders such as flatulence, bloating, diarrhea; (ii) allergic manifestations, such as skin rashes, anaphylaxis and other allergic manifestations; (iii) risk of bacterial or fungal infection; (iv) small-bowel bacterial hyperplasia SIBO, caused by colonic bacteria that thrive in the small intestine and (v) antibiotic resistance because probiotics have resistance genes [11].

Vietnamese Traditional Fermented Foods

Vietnamese traditional fermented foods are classified into two groups: (i) foods requiring fermentation for a short time and (ii) the food needs to be fermented for a long time. Foods produced by short-term fermentation often have a sour taste, are eaten directly or stored at 4-8°C and have a short shelf life. Foods produced by long-term fermentation are high in salt (sodium chloride) to prevent contamination with pathogens. Like other Asian cuisines, the ingredients used to prepare traditional Vietnamese fermented dishes are usually non-dairy and inexpensive and contain a variety of vegetables (e.g., eggplant, radishes, cabbage, bamboo shoots, bean sprouts, leeks, onions, and cucumbers), fruit (for example, the edible fiber of jackfruit, figs, and young mangoes), rice, fish, shrimp, and meat. Herbs and spices such as garlic, black or red pepper, scallions, and ginger are often used as added ingredients. LAB strains play an important role in the fermentation of many foods. Geographically, Vietnam is spread vertically with different soil and climatic conditions depending on the latitude. Thus, traditional fermented foods can be specific for a region, or they can be nationally popular, with only slight variations. These products are often consumed daily as appetizers or side dishes.

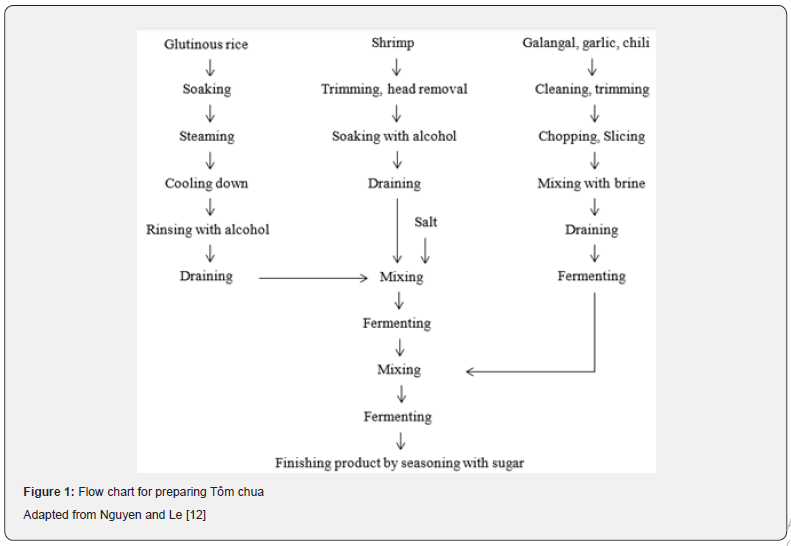

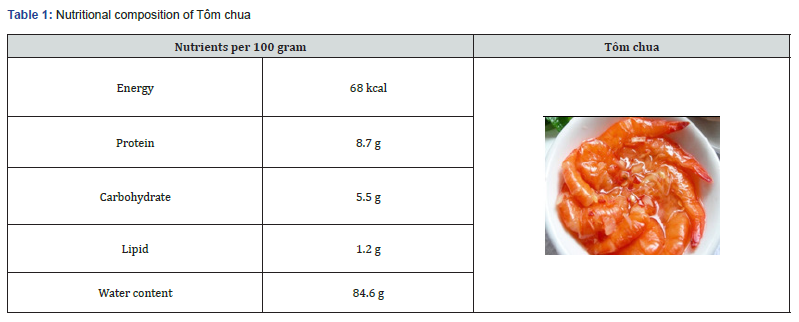

Tôm chua is a kind of fermented shrimp paste, a specialty of the central province of Hue, but popular with consumers across the country. The processing method is as follows: shrimp is cleaned, and edible part separated. Then, it is mixed with steamed glutinous rice (50%-75%, w/w), salt (7.5%-12%, w/w) and spices (galangal, garlic, chili) and fermented. For large-scale production of Sour Shrimp, a mixture of herbs and spices is fermented separately for 3-5 days before being added to a mixture of shrimp and steamed rice, which is fermented separately for 5-7 days. The raw product is fermented for 20-30 days at an ambient temperature of 30-35°C (Figure 1). LAB naturally ferments carbohydrates from steamed glutinous rice to produce lactic acid, giving the product a mild sour taste. During fermentation, the protein from raw shrimp is partially hydrolyzed, making it easier to digest [12] (Table 1).

Fermented sausage (Vietnamese nam, Nem chua)

Product name: Nem chua (Sausage)

Short-term fermentation

Ingredients: Raw pork lean, rind, roasted rice powder, spices, salt.

Probiotics: Lactobacillus plantarum, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Lb. brevis, Lb. farciminis, Lb. brevis, Lactococcus garvieae.

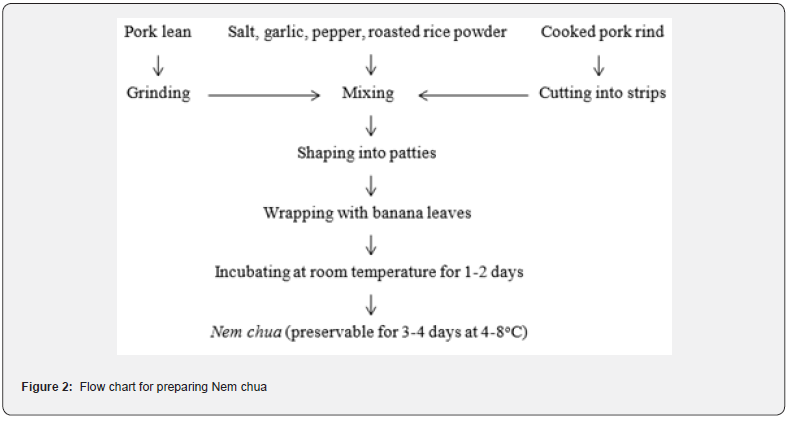

Nem chua is a fermented sausage product that has been relatively fully studied [13-15]. The processing of Nem chua is popular in many different regions of the country (Figure 2). The main ingredients for spring rolls include finely ground pork (95% protein), boiled and sliced pork skin (5% protein), roasted rice powder, salt (about 2%, w/w) and spices as desired (pepper and garlic). Nem chua is processed as follows: the ingredients are mixed according to the recipe and then molded into small balls or cylinders, covered with some herbs such as guava leaves or cloves and a few slices of garlic or chili (depending on the location), wrapped in banana leaf by tightly folding the rolled ends and covered with a larger piece of banana leaf. This careful encapsulation prevents the ingress of air into the mixture, thus creating a relatively anaerobic environment favorable to LAB growth and causing the product to sour and ripen in 1–2 days depending on the condition of ambient temperature (20-37°C). The roasted rice powder used in the traditional method of making Nem chua serves as a carbohydrate source for the growth of the native LAB and contributes to the sour taste. According to a study, the cell density of LAB was 1.3 g (lg (CFU/g)). at the end of fermentation, which was quite high and reduced the pH of the final product to 4.64-4.77, which was necessary to keep the product at acceptable microbiological safety [14].

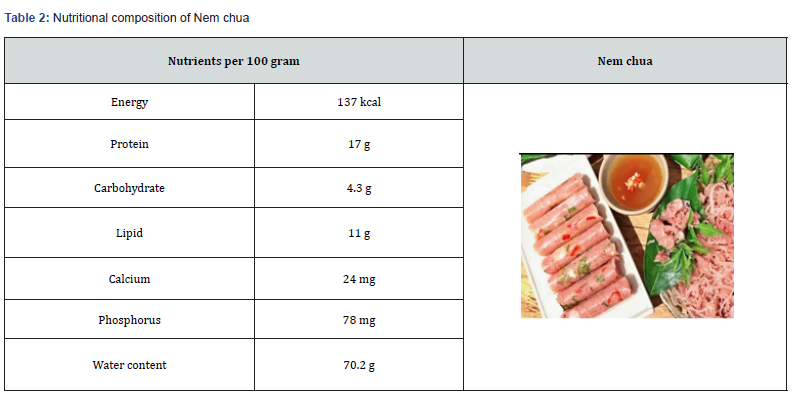

Microbiological analysis on 60 samples of Nem chua taken from different provinces across the country (Hanoi, Thanh Hoa, Hue, and Ho Chi Minh City) and processed in different seasons showed that LAB accounted for 80%–100% of total aerobic bacteria (TABC) in the samples. The predominant natural LAB species in Nem chua are Lactobacillus plantarum (67.6%), Pediococcus pentosaceus (21.6%), Lactobacillus brevis (9.5%), and Lactobacillus farciminis (1.3%) [15]. Lb. plantarum, the most common strain in Nem chua, was used as starter because of its acidity, organoleptic [13-16] and biopreservative properties (related to bacteriocin production) [17–19]. Nem chua obtained from the central province of Hue has other bacteria such as Bacillus amyloliquefaciens N1 that produce high levels of extracellular protease, which promotes the ripening of Nem chua and gives the characteristic texture [20] (Table 2).

Sour fermented pork (Vietnamese name, Thịt lợn chua)

Product name: Thit lợn chua (Sour fermented pork)

Short-term fermentation

Ingredients: Pork, roasted rice powder and spices.

Probitics: Lactic acid bacteria.

Thịt lợn chua, a sour fermented pork, is a traditional fermented food of Phu Tho province, Northwest Vietnam. To produce Sour Pork, the pork is first grilled over charcoal; thinly sliced; mixed with roasted rice flour (20%), salt (about 1.5%), sugar (1%-3%) and spices; and fermented at ambient temperature of about 30°C for 3-5 days. The final product has a characteristic flavor (slightly sour and sweet) and is golden brown in color and can be served with fig or guava leaves. The final product has a moisture content of 64%, a protein content of 17%, a lipid content of 11%, a pH of approximately 5.0 and a LAB density of 8.3 (lg (CFU/g)). After 4 days of storage in the refrigerator, the pH of the product decreased to 4.7 and the LAB density was maintained at the same level. One study that successfully used Lb. plantarum H1.40 was isolated from Nem chua for fermentation for sour pork [21] (Table 3).

Sour fermented fish paste (Vietnamese name, Mắm chua)

Product name: Mắm chua (Sour fermented fish paste) [22-24]

Long-term fermentation

Ingredients: Fresh or sea water, fish, herbs, alcohol, salt, sugar

Probiotics: Lactobacillus sp., Bacillus sp., P. acidilactici, Lb. farcimins, Staphylococcus Hominis.

Mắm chua is the common name of sour fermented fish sauce. Sour sauce is made from different types of fish by different methods. Chau Doc ward in southwestern A Giang province (Mekong Delta) is famous for its production of sour fish sauce, with about 30 varieties being produced in this region. Snakehead fish sauce is a sour fermented sauce made from Channa maculata snakehead fish loin. It is prepared as follows: the fish is mixed with salt (up to 20%, w/w) and roasted rice flour (10%, w/w) and fermented for a long time. Finally, the product is seasoned by adding sugar. The product is served as a side dish or used as an ingredient to prepare other meals [25].

As per a study extending the fermentation time to about 60 days was the most important step in preparation of the product. The level of protease in the supernatant increased slowly during the first 10 days, increased rapidly from 18 to 45 days, and decreased from 45 to 60 days. However, the soluble protein content did not change during this period [26]. The organic acid content gradually increased from day 1 to day 33-36. Furthermore, the TABC in the supernatant increased slowly during the first 15 days and then rapidly increased from 15 to 30 days. In the group of soaked fish, TABC increased steadily from day 30 to day 45 and gradually decreased thereafter. A study isolated 5 strains of salt-loving bacteria from snakehead fish sauce that could tolerate 17% salinity and produce protease. Of these, a strain of Lactobacillus sp. and two strains of Bacillus sp., with high protease activity (1.18 tyrosine units/mL) were identified [22] [Table 3].

Fermented fruit or vegetable (Vietnamese name, Dưa chua)

Product name: Dưa chua (Dưa-muối) (Fermented fruit or vegetable) [27-30]

Short-term fermentation

Ingredients: Fruit or vegetable derived, salt.

Probitics: Lb. fermentum, Lb. pentosus, Lb. plantarum, P. pentosaceus, Lb. brevis, Lb. gaserri.

Dưa chua is the common name for foods derived from sour fermented fruits or vegetables. The traditional method of fermenting fruit/vegetables is simple and involves the following steps: vegetables are cleaned (sometimes dried) and soaked in brine (2%-7% salt and 3%) sugar) to ferment for 1-3 days in closed tanks to achieve optimum acidity depending on the product type. Besides common vegetables used in many other countries such as cabbage, cucumber, mustard greens (Brassica juncea), garlic, onion, green onion, Vietnamese also ferment vegetables such as lotus root, eggplant, jackfruit, bamboo shoots and raw mango. Fermented lotus root contains high levels of vitamin C in the range of 100–150 mg per 100 g of product [31]. Raw mangoes were fermented for 20 days by blanching in 0.5% CaCl2 solution at 75°C for 90 s before soaking in a solution (1:1, w/v) containing 3% salt and 1.5% sucrose. After 4 days of fermentation, LAB concentration reached approximately 1.75 107 CFU/mL, the acidity of 1.59% was equivalent to that of lactic acid [32-35] (Table 4).

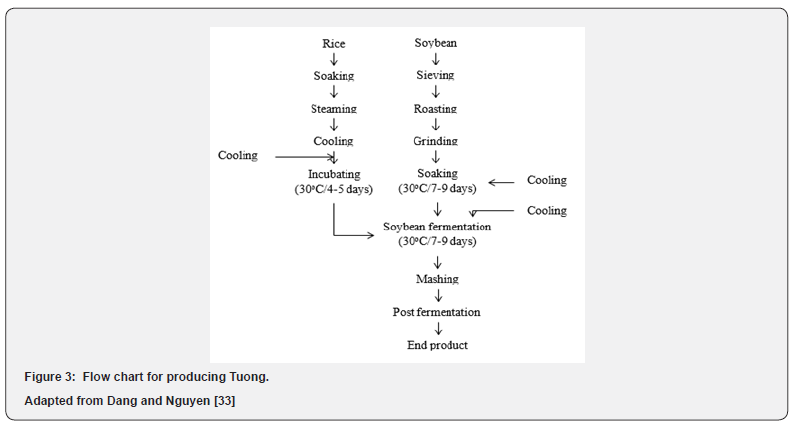

Soybean sauce paste (Vietnamese name, Tương)

Product name: Tương (Soybean sauce paste) [33-35]

Long-term fermentation

Ingredients: Soybean, cooked sticky rice, salt

Probiotics: B. subtiilis, Bacillus sp., Enterobacter mori.

Soy sauce is a typical and popular traditional fermented food. The main ingredients for making soy sauce are soybeans (30%, w/v), glutinous rice (10%, w/v), salt (10%, w/v) and water. The production process of soy sauce is depicted in Figure 4. In summary, steamed rice is incubated with starter yeast containing mainly Aspergillus oryzae at about 30°C for 4–5 days. This acts as a multi-enzymatic agent that hydrolyzes roasted, ground soybeans during the primary fermentation and post-fermentation process. Some other traditional fermented foods are Shrimp paste (salty shrimp paste), Com wine (fermented rice residue after distilling alcohol), Chao (tofu fermented with Actinomucor elegans and Mucor sp.). Seasoning sauce produced by fermentation with Aspergillus sp. are also popular. However, reports of these foods are scarce even though they are described in textbooks [36] (Table 5) (Figure 3).

Fish sauce

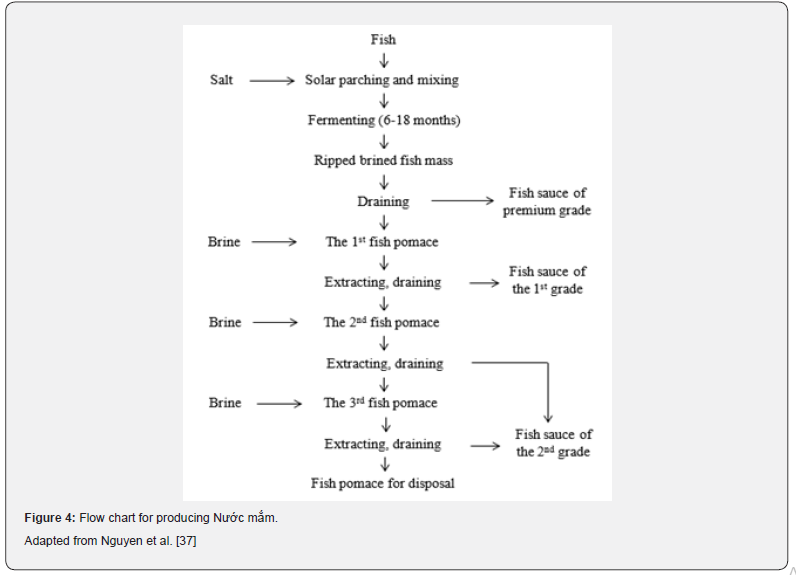

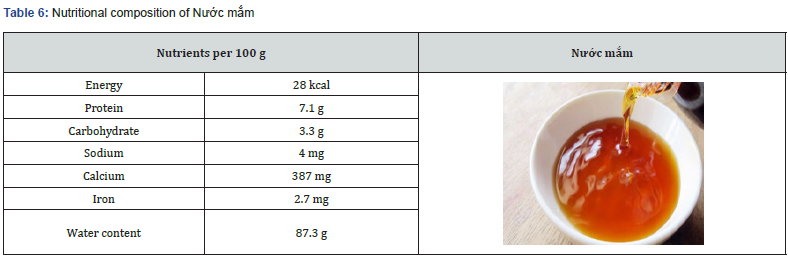

Product name: Nước mắm (Fish sauce) [37]

Long-term fermentation

Ingredients: Sea water fish, salt

Microbial flora: Halophilic, Lb. plantarum, B. subtilis.

Fish sauce is one of the few traditional products produced on a large scale in the country, with an output of about 220 million liters per year [38]. The fish sauce production process is shown in Figure 6 and consists of the following steps: fish and salt are mixed at a ratio of 25%–33% (w/w) in a vessel made of wood, ceramic or cement depending on the local customs production process. After ripening, the extract is withdrawn from the cooked fish, the residue washed several times and filtered to obtain a transparent liquid (fish sauce). The extracts were mixed to obtain different types of products [39]. The traditional method involves fermentation for 12–18 months. Nowadays, the fermentation time is shortened to 6 months by the addition of enzymes from external sources. Anchovies are the most used fish to make fish sauce. The temperature for fermentation and hydrolysis is in the range of 35–50°C. Several strains of microorganisms belonging to the genera Micrococcus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and Lactobacillus have been isolated from fish sauce (Table 6) (Figure 4).

Sour fermented dough (Vietnamese named Cơm mẻ)

Product name: Cơm mẻ (Sour rice fermented paste) [40]

Short-term fermentation

Ingredients: Cooked rice

Probiotics: Lb. plantarum, Lb. paracasei, Lb. casei, Lb. acidophilu.s

Cơm mẻ is a sour fermented dough made from thoroughly cooked wet rice, which is fermented in clean and sealed containers for 7-10 days. Sometimes, fermented products from the previous batch is added to the current batch to speed up the fermentation process. During the fermentation process, the rice changes from a whole grain state to a pickled product and finally to a milky cream with a mild sour aroma. After fermentation, the product is ground and sieved. Broken rice is used as a sour agent in the cooking process and gives the meal a characteristic flavor and sour taste. Batch rice has a pH of 2.9–3.5, moisture content 71%–85%, total protein content 0.27%–0.49%, carbohydrate content 2.9%–5.8% and fat content 0.53%–2.6% depending on the type of rice used. LAB isolation from 28 samples of Com tamarind from 6 provinces along the Mekong Delta (Southern Vietnam) showed the presence of Lb. plants, Lb. paracasei, Lb. casei, and Lb. acidophilic [40].

Future Prospects

Consumer trends towards food choices are changing due to increasing awareness of the link between diet and health [41]. The health benefits of lactic acid bacteria have led to their increased incorporation in dairy and non-dairy foods, leading to the creation of a new generation of healthy foods. Recent studies have demonstrated that adhesion or invasion of beneficial lactic acid bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract area varies with age, sex, and country, due to differences in gut ecology and eating habits [42]. It can be assumed that LAB cultures with probiotic properties, derived from indigenous fermented foods or of human origin may be effective against the host gut due to longer transit times. and the ability to invade in the gut, which results in optimal function for the host. Furthermore, new types or species of LAB with biological properties from traditional fermented foods are not fully documented. It is therefore possible that strains from these products may be more suitable and readily accepted by the local population [43].

With this background, traditional foods may be the best choice for probiotic delivery due to the synergistic effect between the ingredients of the food and the probiotic culture medium. When considering the health benefits and industrial applications, the development of new traditional probiotic products that are naturally enriched in antioxidants and other nutrients during fermentation offers interesting scenes. Probiotics have demonstrated considerable potential as the treatment of choice for a variety of diseases, but the mechanism responsible for these effects has not been fully elucidated. Molecular elucidation of the behavior of probiotics in vivo will help identify new probiotics for the prevention and/or treatment of specific diseases. Given the considerable range of technologies to improve conventional bioprocessing, the challenges, and potential applications of biotechnology in the enhancement of these foods require further research.

Conclusion

Traditional Vietnamese fermented foods are a valuable source of beneficial microorganisms and helpful bacteria, which hold significant importance in daily dietary practices. According to the probiotic selection criteria, bacteria extracted from fermented foods might offer a certain level of effectiveness compared to those sourced from human or dairy products. Specifically, LAB strains play an important role in many traditional fermented foods produced in Vietnam. However, the probiotic function of LAB strains obtained from non-dairy fermented foods in Vietnam remains a relatively unexplored area. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the microbiota isolated from various traditional Vietnamese fermented foods, with an emphasis on uncovering their potential health advantages. Furthermore, it is crucial for considering the advancement of food products and dietary supplements.

References

- Kumar M, Nagpal R, Kumar R, Hemalatha R, Verma V, et al. (2012) Cholesterol-lowering probiotics as potential biotherapeutics for metabolic diseases. Exp Diabetes Res Pp: 902-917.

- Kumar M, Ghosh M, Ganguli A (2012) Mitogenic response and probiotic characteristics of lactic acid bacteria isolated from indigenously pickled vegetables and fermented beverages. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 28: 703-711.

- Banaay CGB, Balolong MP, Elegado FB (2013) Lactic acid bacteria in Philippine traditional fermented foods. Intech Publications. Pp: 571-585.

- Phumkhachorn P, Rattanachaikunsopon P (2010) Lactic acid bacteria: Their antimicrobial compounds and their uses in food production. Ann Biol Res 1(4): 218-228.

- Hugenholtz J (2008) The lactic acid bacterium as a cell factory for food ingredient production. Int Dairy J 18: 466-475.

- Patra F, Tomar SK, Arora S (2009) Technological and functional applications of low-calorie sweeteners from lactic acid bacteria. J Food Sci 74(1): 16-23.

- Kim SK, Guevarra RB, Kim YT, Kwon J, Kim H, et al. (2019) Role of Probiotics in Human Gut Microbiome-Associated Diseases. J Micro Biotechnol 29(9): 1335-1340.

- Ferrarese R, Ceresola ER, Preti A, Canducci F (2018) Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics for weight loss and metabolic syndrome in the microbiome era. Euro Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 22(21): 7588-7605.

- Tang C, Lu Z (2019) Health promoting activities of probiotics. J Food Biochem 43(8): e12944.

- Markowiak P, Śliżewska K (2017) Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients 9(9): 1021.

- Roman P, Abalo R, Marco EM, Cardona D (2018) Probiotics in digestive, emotional, and pain-related disorders. Behavioural pharmacology 29(2-3): 103-119.

- Nguyen AVT, Le BV (2012) Study on technology and equipments to industrially produce fermented shrimp paste. J Food Nutr Sci (Vietnam) 8 (4): 142-150.

- Phan TT, Do HT, Tran HL (2005) Isolation and characterization of Lactobacillus plantarum H1.40, from Vietnamese traditional fermented meat (Nem-chua), in: Proceedings of the Regional Symposium on Chemical Engineering, Hanoi, Vietnam Pp: 121-125.

- Tran KTM, Coloe PJ, Le MT, May BK (2011) Evaluation of the microbiological quality of traditional fermented sausage. J Sci Technol (Vietnam) 49 (1A): 276-283.

- Le MT, Ho HP, Hoang HTL (2011) Exploring the microbiota of Vietnamese fermented food to improve food quality and safety. J Sci Technol (Vietnam) 49 (6A): 93–101.

- Doan NTL, Van Hoorde KP (2012) Validation of MALDI- TOF MS for rapid classification and identification of lactic acid bacteria, with a focus on isolates from traditional fermented foods in Northern Vietnam. Lett Appl Microbiol 55: 265-273.

- Nguyen AL, Dang HT, Nguyen AV (2008) Characterization of bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum NCDN4 with application as starter for quality improvement of traditional fermented products, in: Proceedings of the 4th National Scientific Conference on Biochemistry and Molecular Biology for Agriculture, Biology. Medicine and Food Industry, Hanoi, Vietnam Pp: 260-263.

- Komkhae P, Nguyen CHHC, Doan DND (2013) Identification of bacteriocin- producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional fermented meat “Nem chua” in Mekong delta, Vietnam, in: Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam 2: 294-297.

- Nguyen La Anh, AL, Dang HTJ (2006) Characterization of bacteriocin produced by a strain Lactococcus garvieae, in: Proceedings of the Regional Symposium on Chemical Engineering, Singapore Pp: 187–188.

- Do TTB (2012) The factors affect extracellular protease production of Bacil- lus amyloliquefaciens N1 isolated from Hue ‘Nem chua’. Journal of Science 71 (2): 279-290.

- Phan TT (2011) Study on production of Thanhson (Phutho) fermented meat using starter culture. J Sci Technol (1A): 416-424.

- Pham HHT, Le DDN, Nguyen HC (2013) Isolation and observation the changes of halophilic bacteria density, acid lactic during the fermentation of snakehead fish fillet processing, in: Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam 2: 190-194.

- Do NTT, Luong UU, Nguyen HH (2011) Construction of the sour fermented fish (Trichogaster trichopterus) processing. J Sci Technol (Vietnam) 49(1A): 232-237.

- Tran PM, Do NTT, Nguyen TV (2013) Isolation and enzymatic assays of lactic acid bacteria in sour fermented soft bone fish (Trichogaster trichopterus and Trichogaster microlepsis) in Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam Pp: 421-425.

- Nguyen HC, Pham HHT, Le DDN (2013) Observation of the change of pro- tease and dissolved proteins during the fermentation of snakehead fish fillet. J Sci Technol 51 (6A): 171-176.

- Do TT (2010) Application of commercial bromelain in processing of fermented paste from snakehead fish fillet (Master thesis), Can Tho University.

- Nguyen DT, Van Hoorde, Cnockaert, KM (2013) A description of the lactic acid bacteria microbiota associated with the production of traditional fermented vegetables in Vietnam. Int J Food Microbiol 163(1): 19-27.

- Ho HP, Adams MC (2006) Selection and identification of a novel probiotic strain of Lactobacillus fermentum isolated from Vietnamese fermented food, in: Proceedings of the 20th Scientific Conference of Hanoi University of Technology Pp: 43-49.

- Ho HP, Wills MC (2013) Identification of a potential probiotic strain, Lactobacillus gaseri HA4, from naturally fermented food, in: Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam 2: 157-161.

- Ho HP, Ngo LHT, Le CL (2011) Potential application of Lactobacillus plantarum A17 in vegetable fermentation to inhibit Escherichia coli. J Sci Technol 49 (6A): 276-283.

- Ly TT, Nguyen MV (2013) Factors effecting lactic acid fermentation of lotus root, in: Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam 1: 535-539.

- Tran DM, Tran TT, Nguyen MV (2013) Effect of mild heat pretreatment, sodium chloride and sucrose concentration in brine solution of premature green mango fermented processing in Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam 1: 322-326.

- Dang HT, Nguyen AL (2005) The initial results of the study on bacteria isolated from Soy sauce with fibrenase activity, in: Proceeding of the Regional Symposium on Chemical Engineering Pp: 7-12.

- Nguyen NHT, Nguyen HL (2011) Effect of factors on nattokinase production by isolates from fermented soybean products. J Sci Technol 49 (1A): 381-388.

- Dang XKT, Dinh AQB, Pham HV (2013) Quantification of fibrinolytic enzymes in traditional fermented soybean pastes and identification of related bacteria, in: Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam 2: 664-667.

- Nguyen LD (1998) Traditional Fermented Food, Textbook, University of Technology Hochiminh City. Pp: 20-35.

- Nguyen AVT, Bui HTT, Nguyen TD (2013) Isolation of proteinase- producing halophilic lactic acid and Bacillus bacteria and their application to produce volatile compounds during fish sauce fermentation, in: Proceedings of the National Biotechnology Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam. Pp: 54-59.

- Dung TT (2010) National planning report on development of fish processing towards 2020. Vietnam Institutes of Fisheries Economics and Planning Pp: 37-44.

- Nguyen TX, Bui HTT, Pham DT (2011) Study on quality of fish sauce at production facilities in Vietnam. J Sci Technol (Vietnam) 49(6A): 120-126.

- Tran DN, Bui DTM (2013) Diversity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from “Com me” collected from different ecological regions in Mekong Delta. J Sci (Cantho Univ.) 25B: 58-66.

- Mark-Herbert C (2004) Innovation of a new product category-functional foods. Technovation 24: 713-719.

- Mueller S, Saunier K, Hanisch C, Norin E, Alm L, et al. (2006) Differences in fecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: A cross- sectional study. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 1027-1033.

- Nguyen La Anh AL (2014) Selections of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus strains for probiotics, Project Report “Development of probiotic technology for human use. Food Industries Research Institute P: 48-76.