Ketogenic Diet: Biochemistry, Weight Loss and Clinical Applications

Amar Arnold, Abulhassan Ali, Nagham Kaka and Pramath Kakodkar*

School of Medicine, National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland

Submission: June 22, 2020; Published: July 14, 2020

*Corresponding author: Pramath Kakodkar, School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway University Road, Galway, H91 TK33, Ireland

How to cite this article: Amar A, Abulhassan A, Nagham K, Pramath K. Ketogenic Diet: Biochemistry, Weight Loss and Clinical Applications. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2020. 10(2): 555782. DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2020.10.555782.

Abstract

The ketogenic diet (KD) has obtained immense popularity that stretches beyond its myriad of clinical applications. KD provides a practical solution to attain body recompositing and meet the weight loss target within a short interval. This review aims to eliminate misinformation surrounding the KD as it has now become a fad diet. All the major scientific evidence revolving around the biochemistry, physiology, and weight loss are compiled. A special section is dedicated to the scientific literature published on the usage of KD in the management of diabetes and neurological diseases such as drug-resistant epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Lastly, the short-term and long-term adverse effects with the use of KD are discussed and cautionary contraindications are also listed.

Keywords: Nutritional ketosis; Obesity; Ketogenic diet; Ketogenesis; Weight loss; Epilepsy; Diabetes; Neurological

Introduction

Obesity has a complex multivariate etiology, but it can be managed via lifestyle modifications and dietary alterations. Interestingly, it has always remained in the background as a modifiable factor modulating the mortality and morbidity in a myriad of medical conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease, and hypertension. As such, obesity contributes to the staggeringly high adult mortality rate of 2.8 million per year.

The global trend is alarming as the prediction model still seems to be favoring the positive increasing trends. The WHO statistics in 2016 reported that over 1.9 billion and 650 million adults were overweight and obese, respectively. These obesity prevalence projections remain consistent at local levels and in all age cohorts. Ward et al. fitted a multinomial regressions model that has predicted that by 2030, 48.9% of adults in the US will be obese [1]. The pediatrics cohort has also now joined this predicament. In the UK, the epidemiological data provided by the National Child Measurement Program showed an increase of 0.7% in 4 years within the 10-11-year-old cohort with a baseline obesity prevalence of 20% [2]. Specialized dietary alteration for weight loss can be effective in preventing the rampant rise in obesity. The ketogenic diet consisting of very low caloric contribution by carbohydrates and calorically predominant fat contribution has shown effective and sustainable acute weight loss [3-5].

Review

Utilization of the ketogenic diet

The composite macromolecules are stratified as 55-60% from fats, 30-35% proteins, and 5-10% carbohydrates. This would translate as a person with a baseline 2000kcal intake will require 133.3 g of fat, 175g of proteins, and 25g of carbohydrates.

History of ketogenic diet

Woodyatt et al. reported the production of ketone bodies such as acetone, acetoacetate, and β-hydroxybutyrate in healthy subjects when starved or put on a low-carbohydrate and high-fat diet [6]. Dr. Russel Wilder coined the term ketogenic diet in 1921 and proposed that this diet could be used to treat epilepsy. In the following decade, the ketogenic diet had become standard for the treatment of pediatric epilepsy until the advent of antiepileptics [7-9].

Biochemistry and physiology of ketogenic diet

Stringent carbohydrate restriction below 50g leads to insulin suppression which causes a global catabolic state. After the glycogen reserves are depleted the compensatory metabolic processes gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis occur [10,11]. Gluconeogenesis utilizes lactic acid, glycerol, and glucogenic amino acids as substrates for endogenous glucose synthesis. During prolonged starvation, this constitutional production of endogenous glucose will be outpaced by the metabolic demands of the body. An alternative energy source in the form of ketone bodies via ketogenesis will now become the primary energy source. Due to the low serum glucose levels, insulin secretion is drastically decreased and therefore halts fat and glucose storage. The ketogenesis enzymes are upregulated and hence increase the triacylglycerol catabolism. The resultant fatty acids are broken down into ketones bodies (acetone, acetoacetate, and β-hydroxybutyrate). If the low carbohydrate and high fat state are maintained ketosis will perpetuate. This ketosis state is called nutritional ketosis wherein the serum ketones concentration is within 0.5-3.0mmol/L and there is a compensatory mechanism to maintain the blood pH in the physiologic range (7.35-.45). In the absence of compensation, the serum ketone concentration is >10mmol/L. This can manifest as ketoacidosis or the rare alkaline ketoacidosis (masked DKA).

Endogenous ketone bodies are utilized by the kidneys, cardiac and skeletal muscles, and the neural tissues via the blood-brain barrier. RBCs have no mitochondria and hepatocytes lack the enzyme beta ketoacyl-CoA transferase in its mitochondrial matrix and therefore the only tissues that are unable to utilize ketones. The rate of production of ketones can vary based on the basal metabolic rate, age, and body fat percentage. Interestingly, the utilization of ketones leads to a reduction in the production of reactive oxygen species. The epigenetic modulation is targeted via specific inhibition of the class I histone deacetylases by β-hydroxybutyrate [12]. This causes downregulation in the transcripts of genes FOXO3A and MT2, responsible for oxidative stress resistance [12].

Ketone bodies are more efficient energy production substrates than glucose or fatty acids. Each unit of fatty acids, ketones, and glucose produce 6.7, 5.4, and 5.4 ATPs, respectively [13]. Energy efficiency is better expressed as ATP per oxygen atom ratio (P/O ratio). The P/O ratio for glucose, ketone, and fatty acids is 2.58, 2.50, and 2.33, respectively [13]. There is a need for novel experiments that measure the effect of ketones on cardiomyocytes and skeletal tissue preparation to discern the mechanical work to oxygen output ratio in both physiological and pathological states.

Ketogenic diet for weight loss

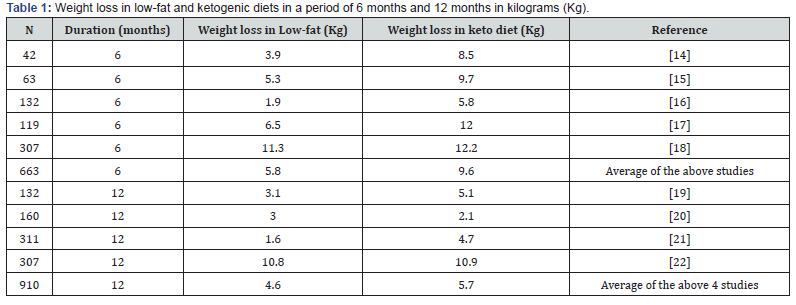

Table 1 [14-22] displays the weight changes over multiple studies comparing weight loss in ketogenic diets and low-fat diets at six and twelve months. An average of 5 studies containing 663 patients was completed for 6 months comparing ketogenic diet weight loss and low-fat diet weight loss. The results present a greater weight loss by a ketogenic diet (9.6Kg) compared to weight loss using low-fat diets (5.8Kg). Importantly, when these dietary plans were carried out for 12 months with an average of 910 patients; there was a much lower difference between the weight loss in the ketogenic diet (5.7Kg) compared to a low-fat diet (4.6Kg). Thus, the conclusion is both diets are beneficial for weight loss; however, ketogenic diets may be more beneficial in the first 6 months compared to low-fat diets. Another metaanalysis of multiple randomized controlled trials at 12 months or longer was carried out comparing a very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) with low-fat diets. The VLCKD group recorded more weight loss over 12 months (average weight difference, -0.91kg; 95% CI: -1.65 to -0.17, in 1415 patients) [22].

Temporal association of weight loss during ketogenic diet

The rapid decrease in weight in the first 2 weeks following a ketogenic diet is often misunderstood as a fat loss when the majority is water loss. This occurs because carbohydrate polymers quench water molecules when stored in the body, and thus low carbohydrate diets cause a diuretic effect in the initial weeks. This water weight can come back rapidly if people begin to consume carbohydrates again.

Physical exam and laboratory changes during the ketogenic diet

The effects of ketogenic diets vs low-fat diets were examined in a meta-analysis of 23 randomized controlled trials with 2788 participants. The results display that in comparison to low-fat diets, a VLCKD diet recorded lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, decreased serum triglyceride levels (-14.0mg/dL; 95% CI: -19.4, -8.7), and elevated HDL levels (3.3mg/dL; 95% CI: 1.9, 4.7). However, a VLCKD diet causes an increased net difference of LDL cholesterol levels in participants (+3.7mg/dL; 95% CI: 1.0, 6.4) [23]. The data supports the conclusion that a reduction of carbohydrates in diets such as the VLCKD diet is adequate for weight loss; however, it is associated with increased total cholesterol levels and the VLCKD diet has not been proven to be clearly more effective than other weight loss methods. In addition, there were no significant differences between VLCKD diets or low-fat diets in the reduction in weight or waist circumference. Finally, it is important to note that this study did not assess the serum ketone levels, thus it is undetermined whether the weight loss is associated with ketosis or any ketogenic effects.

Monitoring ketones

Urine strip is useful to detect ketones during the early phase of nutritional ketosis. Later, there will be a renal adaptation wherein the ketones are reabsorbed, and the urine dipstick will not be sensitive enough [24]. More accurate monitoring is by handheld glucometer (precision Xtra®, Abbott) that has a ketone modality to detect β-hydroxybutyrate. These devices measure blood glucose and ketone levels. In a comparison between urine dipstick and handheld β-hydroxybutyrate testing, a total of 516 hyperglycemic patients were used. The urine dipstick had a sensitivity and specificity of 98.1% and 35.1% respectively. When using handheld testing devices following a cutoff of >1.5mmol/L, the sensitivity and specificity were 98.1% and 78.6% respectively. The inference from these results can be drawn that both urine dipstick and handheld devices both have a high sensitivity for ketones; however, the handheld β-hydroxybutyrate detecting devices have a much higher specificity for ketones, which is important in the case of diabetic patients where this may significantly reduce the number of diabetic patients that enter the emergency department [25].

The breath test has a good correlation with blood β-hydroxybutyrate levels (r=0.821) as well as blood acetone levels. When the concentration of blood β-hydroxybutyrate served as the standard, the sensitivity of exhaled acetone was 90.9% with a specificity of 77.1% [26]. Breath tests have a high sensitivity and specificity, thus making them beneficial as a non-invasive and convenient method of measuring ketones. Importantly in rare situations, people may have false-positive results with an alcohol breath test due to ketogenic diets because of ketonemia. This occurs due to acetone being reduced to isopropanol by hepatic alcohol dehydrogenase in the body, thus giving a false-positive result on alcohol breath tests if inexpensive models are in use.

Clinical Implication

Ketogenic diets can be used in managing a myriad of Neurological disorders, Diabetes, Pre-Diabetes, Cancer, Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, and Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease.

Ketogenic diet in neurology

While modern pharmaceutical drugs are the first-line treatment for epilepsy, there has been a resurgence of the keto diet as a treatment option for drug-resistant epilepsy. The quality of life of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy is often severely negatively impacted, ultimately urging them to try every treatment available for this debilitating illness. The mechanism behind the therapeutic effect of the keto diet in treating epilepsy has been studied extensively on animal models in vivo and in patients with epilepsy in a clinical setting. Kawamura et al. performed a study on mouse and rat models of epilepsy to understand the effect of glucose levels on hippocampal neuronal excitability [27]. In vitro analysis of brain slices of animals that were fed a keto diet for 2-3 weeks showed reduced neuronal excitability, specifically in the seizure-prone region of the hippocampus CA3 [27]. Furthermore, the binding of adenosine to the adenosine A1 receptor (A1R) leads to an inhibitory effect that decreases neuronal excitability. The keto diet increases adenosine levels, which is one possible mechanism for seizure prevention. Kawamura et al. fed A1R knockout animals the keto diet, in which it no longer reduced neuronal excitability in vitro. This study demonstrated the significance of a low glucose diet in reducing neuronal excitability in a seizure-prone area in the brain and a possible physiological mechanism underlying the effect of the keto diet in treating epilepsy.

Patients on a keto diet have less glucose available to be metabolized by the brain for energy, ultimately leading to the utilization of ketone bodies as an alternative energy source. Ketone bodies are metabolized anaerobically, decreasing the energy available and leading to a higher seizure threshold [28]. The Modified Atkins Diet (MAD) is a modified version of the ketogenic diet that has more flexibility and palatability. This renders it better suited for children compared to the ketogenic diet especially since both diets have an equivalent therapeutic value for treating children with drug-resistant epilepsy [29]. There is also evidence for the efficacy of MAD in treating drugresistant epilepsy in adolescents and adults, however, the rate of seizure reduction is lower than that of the children population [28].

There is further evidence for the efficacy of the keto diet in treating other neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [30]. In a study carried out by Henderson et al., patients with AD were given a medium-chain triglycerides drink (MCT) for 3 months and compared them with AD patients that received a placebo drink. Patients that received an MCT drink scored significantly higher on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale. Another study examined the efficacy of the keto diet in treating patients with PD [31]. It was found that patients treated with the keto diet for 4 weeks showed an improvement in their score on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Additionally, there is evidence for the efficacy of the ketogenic diet in rat models for the treatment of brain cancer, neurotrauma, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [30]. The results of these studies on in vivo animal models provide a steppingstone for further research on the efficacy of the keto diet in treating other neurological disorders, which can be worthwhile in patients where pharmaceuticals are proven minimally effective.

Ketogenic diet in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

T2DM patients (n=13) were treated with 2 diets for a duration of 3 weeks. The diet was matched for a caloric intake of 650kcal and protein intake, but one group received low carbohydrates (24g) and the other received high carbohydrates (94g). The low carbohydrate group entered nutritional ketosis confirmed by their serum β-hydroxybutyrate levels [32]. This group had lower fasting glucose levels and Oral Glucose tolerance test (OGGT) glycemia and 22% lower hepatic glucose output (HGO) [32]. This study validates that serum ketone levels have a strong correlation with HGO.

T2D inpatients (n=10) fed on a low carbohydrate (<20g) diet for 2 weeks had a 1.2mmol/L drop in serum glucose drop from a baseline admission glucose of 7.5 mmol/L [33]. A significant improvement in insulin sensitivity shown by 75% in the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp [33]. The hemoglobin A1c dropped 0.5% from a baseline admission reading of 7.3% [33]. The hemoglobin A1c is representative of chronic hyperglycemia over the life span of an RBC (120 days), as such this result must not be given significant weightage. With further investigation, it is seen that a diet with less than 45% carbohydrates that one would have further glycemic control. With the trials investigated following the KD, as the number of restriction increases (like the data point where there are 20% carbohydrates that make up your diet there is a -23% change in HbA1C whereas if there is a greater amount of carbohydrates to approximately 54% there is an increase of +12.5% increasing the amount of HbA1C). More than half of the patients participating in the study using the ketogenic diet in the study had a change in their HbA1C.

Adverse Effects of the Ketogenic Diet

Initiating the ketogenic diet leads to natriuresis in lieu of the low circulating insulin levels. This leads to loss of circulating volume and can manifest as headaches, orthostatic hypotension, fatigue, compensatory tachycardia. If the sodium is not replaced, then the Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System (RAAS) cycle can induce hypokalemia and its resultant sequelae. Long-term usage of the ketogenic diet can cause hepatic steatosis, hypoproteinemia, and vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Importantly, urolithiasis can issue secondary to urine acidification.

Pediatric patients on the ketogenic diet can experience constipation, low-grade acidosis, and hypoglycemia. More rare side effects in these children are kidney stones, dyslipidemia, and diminished growth. The acidosis and the hypercalcemia in the diet are the causes of the stones, and these children tend to have a low baseline acidosis, with HCO3 between 12- and 18 mg/dL. To be more aware, continual screening for stones and potassium bicarbonate is given with a dosage of 2mEq/Kg/Day split within the day as a ratio higher than 0.2. Without evidence of a family history of kidney stones, certain anticonvulsants with carbonic anhydrase inhibition properties that increase the risk of kidney stones should be avoided. None of these however tend to be the reason behind the discontinuation of the keto diet, it is usually due to its inefficiency as a diet (around 3-6 months is the usual time span) that is helping the children with epilepsy.

Contraindication

The ketogenic diet has a relative contraindication in diabetics on insulin or oral hypoglycemics as they need careful optimization of their regiment prior to initiation of this diet. The ketogenic diet has an absolute contraindication in pancreatitis, hepatic failure, congenital fat metabolism errors, porphyrias, and pyruvate kinase deficiency.

Conclusion

The ketogenic diet has been implemented in the management of a myriad of neurological diseases, diabetes, cancers etc. This diet has now been revived beyond its clinical application since KD mirrors the metabolic pathways identified in caloric restriction and longevity. This might make it appealing to the fad culture of dieting, but the short-term benefits must be weighed against the long-term adverse effects and contraindications. KD has shown to cause rapid weight loss of up to 9.6kg within 6 months. Physiological changes associated with the VLCKD include hypotension, and an elevated HDL and LDL. People attempting KD can accurately monitor their ketone levels to verify nutritional ketosis using the handheld glucometer and the ketone breath test. During this COVID-19 period, the ketogenic diet has become a popular and practical solution for rapid weight loss in lieu of the constraints for physical exercise amidst the quarantine.

References

- World Health Organization (2015) Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, Jessica LB, Catherine MG, et al. (2019) Projected U.S. State-Level Prevalence of Adult Obesity and Severe Obesity. N Engl J Med 381(25): 2440-2450.

- Public Health England (2019) National Child Measurement Programme 2019.

- LaFountain RA, Miller VJ, Barnhart EC, Parker NH, Christopher DC, et al. (2019Extended Ketogenic Diet and Physical Training Intervention in Military Personnel. Mil Med 184(9-10): e538-e547.

- Roehl K, Falco-Walter J, Ouyang B, Balabanov A (2019) Modified ketogenic diets in adults with refractory epilepsy: Efficacious improvements in seizure frequency, seizure severity, and quality of life. Epilepsy Behav 93: 113-118.

- Martin-McGill KJ, Lambert B, Whiteley VJ, Wood S, Neal EG, et al. (2019) Understanding the core principles of a 'modified ketogenic diet': a UK and Ireland perspective. J Hum Nutr Diet 32(3): 385-390.

- Woodyatt RT (1921) Objects and Method of Diet Adjustment in Diabetes. Arch Intern Med 28(2): 125-141.

- Talbot FB, Metcalf KM, Moriarty ME (1927) Epilepsy: Chemical Investigations of Rational Treatment by Production of Ketosis. Am J Dis Child 33(2): 218-225.

- Peterman MG (1924) The Ketogenic Diet in the Treatment of Epilepsy: A Preliminary Report. Am J Dis Child 28(1): 28-33.

- Lennox WG, Cobb S (1928) Studies in Epilepsy: VIII. The Clinical Effect of Fasting. Arch Neurol Psych 20(4): 771-779.

- Mohorko N, Černelič-Bizjak M, Poklar-Vatovec T, Gašper G, Saša K, et al. (2019) Weight loss, improved physical performance, cognitive function, eating behavior, and metabolic profile in a 12-week ketogenic diet in obese adults. Nutr Res 62: 64-77.

- Pogozelski W, Arpaia N, Priore S (2005) The metabolic effects of low-carbohydrate diets and incorporation into a biochemistry course. Biochem Mol Biol Edu 33(2): 91-100.

- Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, Wenjuan He, Kotaro Shirakawa, et al. (2013) Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science 339(6116): 211-214.

- Karwi QG, Uddin GM, Ho KL, Lopaschuk GD (2018) Loss of Metabolic Flexibility in the Failing Heart. Front cardiovasc med 5: 68-68.

- Brehm BJ, Seeley RJ, Daniels SR, D’Alessio DA (2003) A Randomized Trial Comparing a Very Low Carbohydrate Diet and a Calorie-Restricted Low Fat Diet on Body Weight and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Healthy Women. JClin Endocrinol Metab 88(4): 1617-1623.

- Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, Brian G McG, Carrie B, et al. (2003) A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N Engl J Med 348(21): 2082-2090.

- Samaha FF, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Kathryn LC, Denise AD, et al. (2003) A Low-Carbohydrate as Compared with a Low-Fat Diet in Severe Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine 348(21): 2074-2081.

- Yancy WS, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EC (2004) A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 140(10): 769-777.

- Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, Angela PM, Diane LR, et al. (2010) Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 153(3): 147-157.

- Stern L, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Kathryn LC, Denise AD, et al. (2004) The effects of low-carbohydrate versus conventional weight loss diets in severely obese adults: one-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 140(10): 778-785.

- Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ (2005) Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. Jama 293(1): 43-53.

- Gardner F, Burton J, Klimes I (2006) Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: outcomes and mechanisms of change. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47(11): 1123-1132.

- Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, da Rocha Ataide T (2013) Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr 110(7): 1178-1187.

- Hu T, Mills KT, Yao L, Kathryn D, Mohamed El, et al. (2012) Effects of low-carbohydrate diets versus low-fat diets on metabolic risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Epidemiol 176 Suppl 7(Suppl 7):S44-54.

- Mitchell R, Thomas SD, Langlois NE (2013) How sensitive and specific is urinalysis 'dipstick' testing for detection of hyperglycaemia and ketosis? An audit of findings from coronial autopsies. Pathology 45(6): 587-590.

- Arora S, Henderson SO, Long T, Menchine M (2011) Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care testing for diabetic ketoacidosis at emergency-department triage: {beta}-hydroxybutyrate versus the urine dipstick. Diabetes Care 34(4): 852-854.

- Qiao Y, Gao Z, Liu Y, Yan C, Mengxiao Y, et al. (2014) Breath ketone testing: a new biomarker for diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of diabetic ketosis. Biomed Res Int 2014: 869186.

- Kawamura M, Ruskin DN, Geiger JD, Boison D, Masino SA (2014) Ketogenic diet sensitizes glucose control of hippocampal excitability. JLipid Res 55(11): 2254-2260.

- D'Andrea Meira I, Romão TT, Pires do Prado HJ, Krüger LT, Pires MEP, et al. (2019) Ketogenic Diet and Epilepsy: What We Know So Far. Front neurosci-switz 13: 5-5.

- Martin K, Jackson CF, Levy RG, Cooper PN (2016) Ketogenic diet and other dietary treatments for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: Cd001903.

- Gano LB, Patel M, Rho JM (2014) Ketogenic diets, mitochondria, and neurological diseases. J Lipid Res 55(11): 2211-2228.

- Tieu K, Perier C, Caspersen C, Peter T, Du-Chu W, et al. (2003) D-beta-hydroxybutyrate rescues mitochondrial respiration and mitigates features of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest 112(6): 892-901.

- Gumbiner B, Wendel JA, McDermott MP (1996) Effects of diet composition and ketosis on glycemia during very-low-energy-diet therapy in obese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr 63(1): 110-115.

- Boden G, Sargrad K, Homko C, Mozzoli M, Stein TP (2005) Effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite, blood glucose levels, and insulin resistance in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med 142(6): 403-411.