Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation with and without Endurance Physical Activity on Components of Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial

Abdel Hamid El Bilbeisi1,3*, Amany El Afifi2, Halgord Ali M Farag3,4 and Kurosh Djafarian3

11Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al Azhar University of Gaza, Palestine

22Faculty of Pharmacy, Al Azhar University of Gaza, Palestine

3Department of Clinical Nutrition, School of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics, Tehran University of Medical Science, International Campus (TUMS-IC), Iran

4Department of Nursing, Sulaimani Polytechnic University (SPU,) Iraq

Submission: November 12, 2019; Published: December 18, 2019

*Corresponding author: Dr. Abdel Hamid El Bilbeisi, Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al Azhar University of Gaza, Palestine

How to cite this article: Abdel Hamid El Bilbeisi, Amany El Afifi, Halgord Ali M Farag, Kurosh Djafarian.Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation with and without Endurance Physical Activity on Components of Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2019. 9(4): 555769. DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2019.09.555769. DOI:10.19080/NFSIJ.2019.09.555769.

Abstract

Background: This study was conducted to determine the effects of vitamin D supplementation with and without endurance physical activity on components of metabolic syndrome in a group of Iraqi adults.

Methods: In this randomized controlled clinical trial, 120 metabolic syndrome patients were recruited. Subjects were randomly assigned to either vitamin D (n=30), vitamin D plus 30 min/day physical activity (n=30), placebo (n=30) and placebo plus 30 min/day physical activity (n=30) groups for 12 weeks. All participants provided three days’ dietary records and three days’ physical activity records throughout the intervention. Fasting blood samples were taken at study baseline and after 12 weeks of intervention.

Results: A total of 120 patients, aged 41.5±5.8 were included in the study. Vitamin D intake led to a significant reduction in SBP compared to the placebo group (-0.034±0.05 vs. 0.01±0.06, P=0.02). In addition, significant changes in serum levels of TC were seen following “vitamin D plus 30 min/day physical activity” intervention compared with the placebo group (-0.02±0.15 vs. 0.06±0.21, P=0.01). However, participants in the placebo group had greater change in WC compared to the vitamin D group (-0.023±0.02 vs. -0.023±0.02, P=0.001). No significant differences were found between the study groups in terms of TG, LDL-C, HDL-C, FPG, weight, BMI and DBP.

Conclusion: Daily supplementation of vitamin D (2000 IU/day), for 12 weeks, along with moderate endurance physical activity, induce a significant reduction in SBP and serum levels of TC in metabolic syndrome patients.

Keywords: Iraq; Metabolic syndrome Physical activity Vitamin D

Abbrevations: SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure; TC: Total Cholesterol; WC: Waist Circumference; TG: Triglyceride; LDL-C: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; HDL-C: High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; FPG: Fasting Plasma Glucose; BMI: Body Mass Index; DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure; Mets: Metabolic Syndrome; BP: Blood Pressure; USA: United State Of America; Met: Metabolic Equivalent; IDF: International Diabetes Federatio

Trial Registration

World Health Organization, International Clinical Trails Registry Platform. Registered 01 February 2018. (Code: IRCT20161110030823N2).

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS), a clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors including central obesity, dyslipidemia, elevated fasting plasma glucose, elevated blood pressure (BP) and insulin resistance [1], is a major public health problem in both developed and developing countries [2]. This syndrome affects 10-25% of adult population worldwide [3]. In the USA, 22.5% of adults are affected by this condition [4]. The etiology of this syndrome is not fully understood; however, lifestyle factors including dietary intakes might contribute to the etiology of the syndrome [5].MetS is linked with increased risk of chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer [2]. Therefore, investigation on potential risk factors and preventive strategies of MetS is of great importance.

Previous studies examined the effects of several macro- and micronutrients on MetS [6]. Recently, the effect of vitamin D on MetS components has attracted great interest. Observational studies suggested that serum levels of 25(OH)D are lower among those with the MetS [7]. Previous studies examined the effects of vitamin D in MetS patients. For instance, four months’ supplementation with high dose vitamin D decreased serum levels of triglycerides (TG) in MetS patients but it did not affect other cardiometabolic risk factors [8]. A pilot randomized study showed that 2000 IU/day vitamin D supplementation did not affect various cardiovascular risk factors among MetS patients [9]. Previous systematic review and meta-analysis showed that lifestyle modification in MetS patients decreased the severity of MetS abnormalities [10]. It seems that physical activity level of patients’ needs to be considered [11]. Doing regular endurance physical activities and consuming the antioxidants are among the advised solutions, which are not only affecting the total safety of body, but also affect brain performance [12]. Some of previous studies have reported that people who experience delayed performance physically showed improvement with supervised physical fitness exercises, and the health of people suffering from metabolic diseases improved with an increase in antioxidant intake into their system [13]. Although deficiency and insufficiency of vitamin D was prevalent among patients with the MetS, limited clinical trials are available in this regard. Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent worldwide [14]; however, the effects of vitamin D on MetS is not fully elucidated. In addition, no study is available that considered the effects of vitamin D supplementation plus endurance physical activity on components of MetS. Therefore, the aim of this randomized controlled clinical trial was to examine the effects of vitamin D supplementation with and without endurance physical activity on components of MetS in a group of Iraqi adults.

Material and methods

Study design

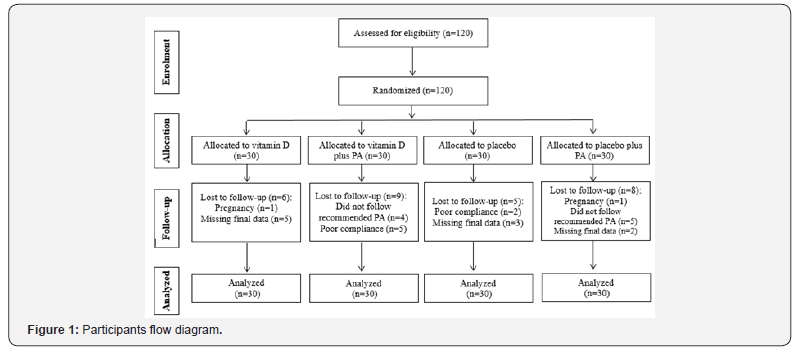

This a parallel randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was performed between March 2016 and May 2016 in the Halabja hospital, Kurdistan region of Iraq. During the study visit, a standardized questioner was filled to get information from the subjects. In addition, information regarding demographic and medical history variables was obtained with an interviewbased questionnaire. Past history and any previous treatment for certain disease including hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, supplement used, family history of obesity, family history of diabetes, family history of hypertension as well as physical activity patterns were also recorded. Then, participants were randomly divided into four groups: group A received vitamin D supplements(2000IU/day) without endurance physical activity (n=30), group B received vitamin D (2000IU/day) plus 30 min/day endurance physical activity (n=30), group C received one placebo of vitamin D plus 30min/day endurance physical activity (n=30), and group D received one placebo of vitamin D/day without endurance physical activity (n=30) (Figure 1). All investigators and participants were blinded to the random assignments. The vitamin D supplements and placebos were soft gels manufactured by Osweh Company (Tehran, Iran). Placebos were on the same shape, odor and size of the vitamin D supplements. Participants were asked to use vitamin D supplements and placebos for 12 weeks. Compliance of study participants with the vitamin D supplements was assessed through serum vitamin D quantification. To ensure that all participants maintained their habitual diets throughout the study, all participants provided 3-day dietary recalls (one weekend day and 2 weekdays). Furthermore, participants were asked to record their daily physical activity during intervention for three days. Then, metabolic equivalent (MET) of physical activities was calculated for each participant. In terms of ethics as well as to avoid any confounding effects from dietary changes throughout the study, dietary recommendation was given to all participants after final intervention. Physical activity recommendations were given to all participants as well at the end of trial.

Study participants

The sample size for this study was calculated based on suggested formula for parallel clinical trials [15]. We considered type 1 error of 5%, type 2 error of 20% (power=80%) and fasting plasma glucose as a key variable and reached the sample size of 21 subjects for each group. To consider probable dropout throughout the study, we enrolled 30 patients in each group. Totally, 120 patients aged 30-60 years were included in this study. MetS was defined according to International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria [16]. Presence of three or more of the following criteria was considered as MetS: waist circumference (WC) ≥94 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women, hypertriglyceridemia (serum TG levels ≥150 mg/dl), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <40 mg/dl in male and <50 mg/dl in female, elevated BP (Systolic BP (SBP) ≥130 or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥85 mmHg), and elevated fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥100 mg/dl. Individuals who were using any kind of minerals, vitamins and medications, diabetic patients, smokers, alcohol users, pregnant or lactating women, post-menopausal women, patients with a history of bariatric surgery and those that were on a weight loss diet were not included. We also did not include those with a high TG levels (more than 400 mg/dl), those with high systolic or diastolic BP (higher than 140/90 mmHg).

Assessment of anthropometric measurements

Weight was measured to the nearest 100g using a calibrated digital scale while the subject wearing minimal cloths without wearing shoes. Height was measured using a wall mounted stadiometer Seca to the nearest 0.1 cm in standing positionwithout wearing shoes while shoulders were relaxed. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard equation as weight in kilogram divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). WC was measured at the mid-way between the lower border of the ribs and the iliac crest, while the participants in standing position. Using an un-stretched tape measure, without any pressure to body surface, measurement was recorded to the nearest 0.1cm. To avoid subjective error, all measurements were taken by the same technician. BP was measured at morning time in the seated position using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer after at least 15 minutes of rest [17].

Biochemical assessments

Fasting blood samples were collected at baseline and 12 weeks of intervention after 12 hours overnight fasting to quantify serum levels of glucose, total cholesterol (TC), HDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), TG, and 25(OH)D. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was measured on the day of blood collection by enzymatic colorimetric method using glucose oxidase [18]. Serum TC and TG concentration were assayed using enzymatic colorimetric tests with cholesterol esterase and cholesterol oxidase and glycerol phosphate oxidase, respectively, by using standard kits. HDL-C was measured after precipitation of the apolipoprotein B containing lipoproteins with phosphotungistic acid. LDL-C was calculated from serum TC, TG and HDL-C based on relevant formula [19]. Serum Vitamin D was measured by the clinical laboratory at the Slemani Hospital, Iraq, using the Modelvidas analyser (Biomerux, Italy) [20]. In addition, vitamin D insufficiency was defined as a 25(OH)D serum level below than 30 ng/ml whereas deficiency was defined when the 25(OH)D level was below than 15 ng/ml [21].

Statistical analysis

We used Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to examine the normal distribution of variables. The analyses were done based on intention-to-treat approach. Missing values were treated based on Last-Observation-Carried-Forward method. Baseline general characteristics among different groups were examined using one-way ANOVA for continuous variable and a chi-square test for categorical variables. To determine the effects of vitamin D supplementation and endurance physical activity on glucose metabolism, lipid profiles, and BP, we used one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons to identify pairwise differences. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

In the present study, 120 patients with MetS were recruited: vitamin D (n=30), “vitamin D plus 30 minutes/day physical activity” (n=30), placebo (n=30) and “placebo plus 30 minutes/ day physical activity” (n=30) groups. The study procedure is shown in Figure 1. In the present study, 28 participants excluded from the study because of the following reasons: two became pregnant, nine did not follow recommended physical activity, seven had poor compliance to vitamin D supplements (Compliance of study participants with the vitamin D supplements was assessed through serum vitamin D quantification), and 10 did not complete the trial. Finally, 92 subjects remained in the study. Using an intention-to-treat approach, we included the data for all 120 participants in the final analysis.

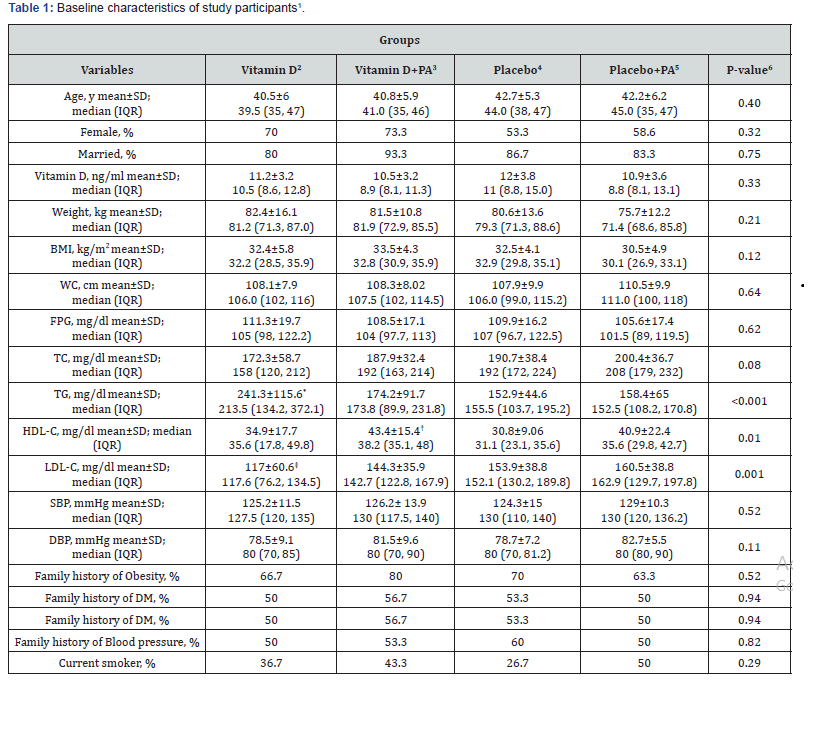

Baseline characteristics of study participants are provided in Table 1. The distribution of participants in terms of age, sex, marital status, smoking status, family history of obesity, diabetesmellitus, BP, serum vitamin D levels, weight, BMI, WC, SBP, DBP, FPG and TC levels were not significantly different among the four intervention groups. In addition, Table 1 show that, participants who received vitamin D supplements had higher serum levels of TG compared with those who received placebo or “placebo plus physical activity” (241.3±115.6 vs. 152.9±44.6 and 158.4±65, P<0.001). Participants in the “vitamin D plus physical activity” group had higher values of HDL-C compared with those in the placebo group (43.4±15.4 vs. 30.8±9.06, P=0.01). Furthermore, participants in the vitamin D group had lower levels of LDL-C compared with those in the “placebo plus physical activity” group (117±60.6 vs. 160.5±38.8, P=0.001).

1Data are mean ± standard deviation (SD)

2Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day

3Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

4Receiving one placebo per day

5Receiving one placebo per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

6Obtained from ANOVA or chi-square test, where appropriate

*P<0.05 compared with the other groups, using Tukey’s test

†P<0.05 compared with the placebo group, using Tukey’s test

‡P<0.05 compared with the placebo plus physical activity group, using Tukey’s test

IQR: Interquartile range; PA: physical activity; BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumferences; DM: diabetes mellitus, FPG: fasting plasma glucose; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure

On the other hand, we observed a significant increase in mean serum vitamin D concentrations in participants who received vitamin D (11.2±3.2 ng/ml at study baseline vs. 21.1±6.2 ng/ml at the end of the study, P<0.001) or “vitamin D plus physical activity” (10.5±3.2 ng/ml at study baseline vs. 23.5±9.8 ng/ml at the end of the study, P<0.001). No significant changes in serum levels of vitamin D were seen in participants in the placebo group (12±3.8 ng/ml at study baseline vs. 12.4±3.9 ng/ml at the end of the study, P=0.09). There was also a significant increase in serum levels of vitamin D in those who received “placebo plus physical activity” (10.9±3.6 ng/ml at study baseline vs. 16.7±5.5 ng/ml at the end of the study, P<0.001).

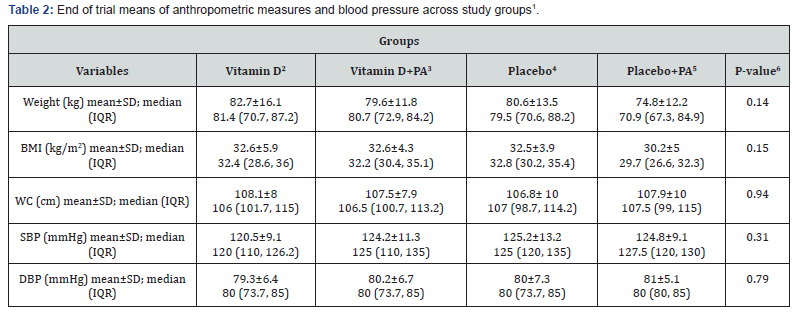

1Data are means ± standard deviation (SD)

2Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day

3Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

4Receiving one placebo per day

5Receiving one placebo per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

6Obtained from ANOVA

IQR: Interquartile range; PA: physical activity; BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumferences; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure

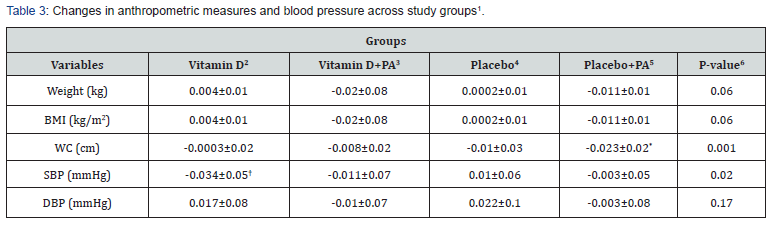

1Data are means ± standard deviation (SD)

2Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day

3Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

4Receiving one placebo per day

5Receiving one placebo per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

6Obtained from ANOVA

*P<0.05 compared with the vitamin D group

†P<0.05 compared with the placebo group

PA: physical activity; BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumferences; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure

End of trial means of anthropometric measures as well as BP among study groups are shown in Table 2. Vitamin D supplementation did not significantly affect means of anthropometric measures and BP. Changes in anthropometric measures and BP across study groups are presented in Table 3. Participants in the “placebo plus physical activity” group had greater changes in WC compared with the vitamin D group (-0.023±0.02 vs. -0.0003±0.02, P=0.001). In addition, participants in the “vitamin D plus physical activity” group had slightly higher reduction in weight and BMI compared with the vitamin D group (P=0.06). Moreover, vitamin D intake led to a significant reduction in SBP compared to the placebo group (-0.034±0.05 vs. 0.01±0.06, P=0.02). Although, we did not find any significant differences in weight and BMI among the four groups.

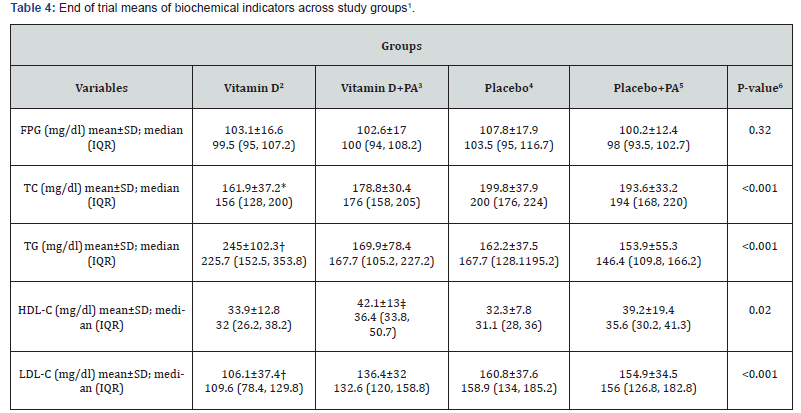

End of trial means of biochemical indicators across four study groups are shown in Table 4. After intervention, subjects in vitamin D group had lower serum levels of TC compared with the placebo and “placebo plus physical activity” groups (161.9±37.2 vs. 199.8±37.9 and 193.6±33.2, P<0.001). In addition, subjects in vitamin D group had higher serum levels of TG compared with the “vitamin D plus physical activity”, placebo, and “placebo plus physical activity” groups (245±102.3 vs. 169.9±78.4 and 162.2±37.5 and 153.9±55.3, P<0.001). Additionally, participants in vitamin D group had higher serum levels of HDL-C compared with placebo group (33.9±12.8 vs. 32.3±7.8, P=0.02). Moreover, end of trial means of serum levels of LDL-C was significantly lower in the vitamin D group compared with all of other groups (106.1±37.4 vs. 136.4±32 and 160.8±37.6 and 154.9±34.5, P<0.001).

1Data are means ± standard deviation (SD)

2Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day

3Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

4Receiving one placebo per day

5Receiving one placebo per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

6Obtained from ANOVA

*P<0.05 compared with the placebo and “placebo plus physical activity” groups

†P<0.05 compared with the other groups

‡P<0.05 compared with the placebo group

IQR: Interquartile range; PA: physical activity; FPG: fasting plasma glucose; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

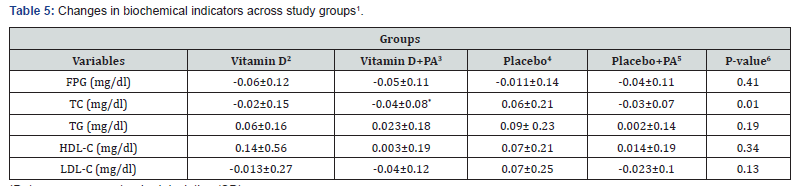

Finally, changes in biochemical indicators across study groups are presented in Table 5. A significant change in serum levels of TC were seen following “vitamin D plus physical activity” than that in the placebo group (-0.02±0.15 vs. 0.06±0.21, P=0.01). There was no significant difference in changes of FPG, TG, LDL-C and HDL-C among the four groups.

1Data are means ± standard deviation (SD)

2Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day

3Receiving 2000 IU vitamin D per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

4Receiving one placebo per day

5Receiving one placebo per day plus 30 minutes’ endurance physical activity

6Obtained from ANOVA

*P<0.05 compared with the placebo group

PA: physical activity; FPG: fasting plasma glucose; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which evaluate the effects of vitamin D supplementation with and without endurance physical activity on components of MetS in Iraqi adults. The main findings of this study indicate that, daily supplementation of vitamin D (2000 IU/day), for 12 weeks, along with moderate endurance physical activity, induce a significant reduction in SBP and serum levels of TC in MetS patients. In addition, we did not find any significant effect of vitamin D and “vitamin D plus physical activity” interventions on serum levels of FPG, TG, LDL-C and HDL-C as well as on weight, BMI and DBP. Furthermore, we observed a significant increase in serum levels of TG in subjects received vitamin D supplements; however, these subjects had higher levels of serum TG at study baseline. There was no significant change in serum TG levels after intervention. In agreement with our study, Salekzamani et al. [8] found no effect of vitamin D intake on FPG, LDL-C and HDL-C. However; in contrast to our findings, that study observed a significant effect of vitamin D intake on serum TG levels but not on serum TC levels. Zittermenn et al. [22] showed a significant decrease in serum levels of TG after 12 months’ vitamin D supplementation. In addition, Mohammadi et al. [23] did not find any significant effects of vitamin D intake on FPG, TG and TC. This discrepancy of the findings might be due to different participant’s characteristics, dosage of vitamin D supplementation and duration of interventions across studies.

In the present study, vitamin D intake did not significantly effect on weight, WC and BMI; however, we observed a significant decrease in WC in the placebo plus physical activity group compared with the vitamin D groups. Earlier study among women with overweight and obesity found that 3 months of vitamin D supplementation resulted in a significant reduction in WC [24]. Sadiya et al. [25] in a clinical trial, showed no significant influenceof vitamin D supplementation on weight and WC in subjects with obesity and type 2 diabetes. In the study of Salekzamani et al. [8] 50000 IU vitamin D intake weekly for 16 weeks did not influence on WC in subjects with MetS. Such findings have been reported in another clinical trial on healthy overweight and obese women [26]. Different findings could be explained by the discrepancy in recruited subjects in terms of their health conditions, dosage of vitamin D supplementation and duration of interventions. It is also possible that vitamin D intake had favourable effects on anthropometric measures among subjects with normal levels of vitamin D; however, participants in our study had vitamin D deficiency.

We found a significant reduction in SBP after vitamin D supplementation. In line with our findings, a pilot randomized study showed that 2000 IU/day vitamin D intake in MetS patients resulted in significant reduction in SBP [7]. Nasri et al. [27] found that weekly 50000 IU vitamin D supplementation for 12 weeks had beneficial effects on BP. However, another clinical trial study among MetS patients observed no significant effects of 16 weeks’ vitamin D intake on BP [8]. Characteristics of study participants as well as dosage of vitamin D supplementation and duration of interventions might explain, at least in part, the discrepancy between studies. It has been shown that physical activity is a protective factor for MetS [28]. We expected that vitamin D supplementation plus endurance physical activity influence on MetS components; however, we didn’t observe any effects except for TC which is significantly decreased in “vitamin D plus physical activity” group compared with the placebo group. The effects of physical activity on MetS development might be depend on the frequency and duration of physical activity.

Several possible mechanisms have been suggested for the favourable effects of vitamin D intake on MetS features. VitaminD might improve insulin secretion; therefore, it can influence on lipid metabolism indirectly [29]. It has been shown that vitamin D acts as a negative regulator of the renin-angiotensin system [30]. Therefore, vitamin D could have favourable effects on BP.

Our study has some limitations that must be considered in the interpretation of our results. We used single measurement of metabolic variables instead of repeated measures. However, metabolic variables have day-to-day variation. Therefore, multiple measurements would address these variations much more sufficiently. In addition, we did not assess participants’ sunlight exposure. Finally, the current study has adequate power to detect the significant effects of vitamin D; however, further studies with longer duration of interventions might be needed to confirm the long-term benefits of vitamin D supplementation in patients with MetS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, daily supplementation of vitamin D (2000 IU/day), for 12 weeks, along with moderate endurance physical activity, induce a significant reduction in SBP and serum levels of TC in MetS patients. Further studies with log-term duration are needed in this area to investigate the effects of vitamin D supplementation in the prevention and treatment of MetS.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.TUMS. REC.1395.2832) and the trial was registered at the World Health Organization, International Clinical Trails Registry Platform (Code: IRCT20161110030823N2). In addition, written informed consent was also obtained from each participant

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Authors’ contributions:

AHB, AA, HF and KD participated in the design of the study, data collection, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. KD and AHB supervising the study and participated in draft review. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Acknowledgments

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors would like to thank all participants for their great cooperation.

References

- Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, et al. (2009) Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120(16): 1640-1645.

- O'Neill S, O'Driscoll L (2015) Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev 16(1): 1-12.

- Wild S, Byrne CD (2005) The global burden of the metabolic syndrome and its consequences for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. In Metabolic Syndrome. Wild S & Byrne CD, Eds. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, England, UK, pp. 1-32.

- Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH (2002) Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA 287(3): 356-359.

- El Bilbeisi AH, Hosseini S, Djafarian K (2017) Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza Strip, Palestine. Ethiop J Health Sci 27(3): 227-238.

- Djousse L, Padilla H, Nelson T, Gaziano J, Mukamal K (2010) Diet and metabolic syndrome. Endocr, Meta & Immune Disord Drug Targets 10(2): 124-137.

- Bea JW, Jurutka PW, Hibler EA, Lance P, Martinez ME, et al. (2015) Concentrations of the vitamin D metabolite 1,25(OH)2D and odds of metabolic syndrome and its components. Metabolism 64(3): 447-459.

- Salekzamani S, Mehralizadeh H, Ghezel A, Salekzamani Y, Jafarabadi MA, et al. (2016) Effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on cardiometabolic risk factors in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled double-blind clinical trial. J Endocrinol Invest 39(11): 1303-1313.

- Makariou SE, Elisaf M, Challa A, Tentolouris N, Liberopoulos EN (2017) No effect of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a pilot randomised study. Arch Med Sci Atheroscler Dis 2: e52-e60.

- Yamaoka K, Tango T (2012) Effects of lifestyle modification on metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 10:138.

- Hoseini R, Damirchi A, Babaei P (2017) Vitamin D increases PPARγ expression and promotes beneficial effects of physical activity in metabolic syndrome. Nutrition 36: 54-59.

- Ebrahimpour P, Fakhrzadeh H, Heshmat R, Ghodsi M, Bandarian F, et al. (2010) Metabolic syndrome and menopause: A population-based study. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 4(1): 5-9.

- Freiberger E, Haberle L, Spirduso WW, Rixt Zijlstra GA (2012) Long‐term effects of three multicomponent exercise interventions on physical performance and fall‐related psychological outcomes in community‐dwelling older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 60(3): 437-446.

- Holick MF, Chen TC (2008) Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr 87(4):1080s-1086s.

- Kaftan AN, Hussain MK (2015) Association of adiponectin gene polymorphism rs266729 with type two diabetes mellitus in Iraqi population. A pilot study. Gene 1;570(1): 95-99.

- El Bilbeisi AH, Hosseini S, Djafarian K (2017) The association between physical activity and the metabolic syndrome among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza strip, Palestine. Ethiopian journal of health sciences 27(3): 273-282.

- El Bilbeisi AH, Hosseini S, Djafarian K (2017) Association of dietary patterns with diabetes complications among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza Strip, Palestine: a cross sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr 36(1): 37.

- Guilbault GG, Brignac PJ, Zimmer M (1968) Homovanillic acid as a fluorometric substrate for oxidative enzymes. Analytical applications of the peroxidase, glucose oxidase, and xanthine oxidase systems. Analytical Chemistry 40(1): 190-196.

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS (1972) Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 18(6): 499-502.

- Kamisaki-Horikoshi N, Okada Y, Takeshita K, Takada M, Kawamoto S, et al. (2017) Evaluation of TA10 Broth for Recovery of Listeria monocytogenes from Ground Beef. J AOAC Int 100(2): 470-473.

- Kumar J, Muntner P, Kaskel FJ, Hailpern SM, Melamed ML (2009) Prevalence and associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in US children: NHANES 2001–2004. Pediatrics 1;124(3): e362-e70.

- Zittermann A, Frisch S, Berthold HK, Gotting C, Kuhn J, et al. (2009) Vitamin D supplementation enhances the beneficial effects of weight loss on cardiovascular disease risk markers. Am J C Nutr 89(5): 1321-1327.

- Mohammadi SM, Eghbali SA, Soheilikhah S, Ashkezari SJ, Salami M, et al. (2016) The effects of vitamin D supplementation on adiponectin level and insulin resistance in first-degree relatives of subjects with type 2 diabetes: a randomized double-blinded controlled trial. Electron Physician 8(9): 2849-2854.

- Roosta S, Kharadmand M, Teymoori F, Birjandi M, Adine A, et al. (2018) Effect of vitamin D supplementation on anthropometric indices among overweight and obese women: A double blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr [Epub ahead of print]

- Sadiya A, Ahmed SM, Carlsson M, Tesfa Y, George M, et al. (2016) Vitamin D3 supplementation and body composition in persons with obesity and type 2 diabetes in the UAE: A randomized controlled double-blinded clinical trial. Clin Nutr 35(1): 77-82.

- Salehpour A, Hosseinpanah F, Shidfar F, Vafa M, Razaghi M, et al. (2012) A 12-week double-blind randomized clinical trial of vitamin D(3) supplementation on body fat mass in healthy overweight and obese women. Nutr J 11: 78.

- Nasri H, Behradmanesh S, Ahmadi A, Rafieian-Kopaei M (2014) Impact of oral vitamin D (cholecalciferol) replacement therapy on blood pressure in type 2 diabetes patients; a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. J Nephropathol 3(1): 29-33.

- Kim JY, Yang Y, Sim YJ (2018) Effects of smoking and aerobic exercise on male college students' metabolic syndrome risk factors. J Phys Ther Sci 30(4): 595-600.

- Kamycheva E, Jorde R, Figenschau Y, Haug E (2007) Insulin sensitivity in subjects with secondary hyperparathyroidism and the effect of a low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level on insulin sensitivity. J Endocrinol Invest 30(2):126-132.

- Yuan W, Pan W, Kong J, Zheng W, Szeto FL, et al. (2007) 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses renin gene transcription by blocking the activity of the cyclic AMP response element in the renin gene promoter. J Biol Chem 282(41): 29821-29830.