Livelihood Strategies Resource and Nutritional Status of Forest dependent Primitive Tribes Chenchu in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana States

Sreenivasa Rao J1*, Shivudu G1, Hrusikesh Panda2 and Kalyan Reddy P3

1Food Chemistry Division, National Institute of Nutrition, (ICMR), India

2Publication, Extension & Training Division, National Institute of Nutrition, (ICMR), India

3Tribal Cultural Research and Training Institute, Govt of Telangana, India

Submission: December 01, 2018; Published: February 11, 2019

*Corresponding author: Sreenivasa Rao J, Food Chemistry Division, National Institute of Nutrition, (ICMR), India

How to cite this article: Sreenivasa Rao J, Shivudu G, Hrusikesh P, Kalyan R P. Livelihood Strategies Resource and Nutritional Status of Forest dependent Primitive Tribes Chenchu in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana States. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2019. 8(2): 555735. DOI:10.19080/NFSIJ.2019.08.555735.

Abstract

Back Ground: Food consumption and food safety issues among tribal communities are not well characterized. Tribal population in India is the second largest in the world, next only to Africa, constituting 8.6% of total Indian population. The Andhra Pradesh (AP) and Telangana (TS) states have 33 tribal ethnic groups constituting about 6.7% of the state’s population. Among these, Chenchu tribes were considered as forest-dependent tribes and about 64% of these are below poverty line. They depend on natural resources for 90% of their food supply and their economy is closely associated with the ecosystem and the habitat of that region. Health concerns vary widely among the tribes, however, health indicators fall below that of the population living in urban areas which could be due to inaccessibility, and also to other reasons such as literacy, personal hygiene and economic status and so on.

Methods: The goal of present work is to explore the information and do a review on the available literature on livelihood strategies resource and nutritional status of primitive tribes chenchu in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana States. Electronically accessible databases were searched, and the findings were collated for analysis and interpretation of the results.

Results: The average daily consumption of all the food stuffs (g/CU/day) by Chenchu tribes is lower than the recommended dietary levels. In general cereals, particularly rice formed the major proportion of the diet contributing to 91% of RDI. The nutrient intake in Chenchu tribes was marginally lower than the tribal populations of India, in both the states. However, the prevalence of under nutrition among preschool children (37.13 %) was lower, than that reported for the tribal communities in the state of combined AP (40.66%). The Chronic Energy Deficiency (CED) among adults was about 41%. NNMB report on tribes revealed that the increase in the prevalence of diet related chronic diseases is evident among Chenchu tribes.

Conclusion: The reasons attributable may be poverty and consequential under nutrition, lack of awareness, access to and utilization of the available nutrition supplementation programmes, poor environmental sanitation and lack of safe drinking water, which mainly leads to increased susceptibility to water-borne infections. The facilities of health care and its accessibility is also resulting in increasing severity and /or duration of a variety of ailments. Since high morbidity is noticed in tribal population, a series of effective measures are needed to be taken up to improve the nutrition status, sanitation and personal hygiene among citizens of Chenchu tribes.

Keywords: Chenchu Tribes; Nutrition; Health Problems; NNMB; RDI

Introduction

Food habits of the indigenous population across the globe are very peculiar, when compared that of civilized people. The estimated indigenous population living in 70 countries is 370 million. These tribes are situated largely in Central Africa, South America, Oceania, India and Australia. India is known to large the second largest tribal population of the globe next only to African continent. There are 450 tribes sub divided into 461 groups, spread over the length and breadth of country and concentrated mostly in the hills and forest regions. These tribes were initially residing in the planes and river valleys, but after the invasions of Aryans, had retreated to hilly forested and mountains area for their own security. Tribes are the original dwellers of India, who were pushed from the productive plains in to the more unreachable, remote, inhospitable slopes, hills and forests by straight ware of attackers. Now over the centuries, they have accepted there in hospitable habitat permanently. According to Aijazuddin Ahmed [1] presence of tribes in these regions at their present concentration, was due to the outcome of the dynamics of ethnic displacement within the country. Plenty of tribal folklore from all regions of country bears reference to the history of displacement of tribes from their earlier habitat. Presently, the tribes usually live by the fringe of the river valleys, in forested hills or upland tracts [1].

Unfortunately, even after 70 years of independence, tribes are for removed from civilization, lying at the lower strata of development and being demoralized for generations. The constitution of India up holds security, justice, liberty, equality and fraternity for all citizens. Nutrient food and good health are rights of every citizen, but the tribal people are suffering with severe malnutrition problems due to ignorance. According to World Health Organization (WHO-1946), health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity [2]. Health status is one important criteria of human development and it is a affirmative right of every citizen.

The term 'tribe' originated around Greek period, during the early development of the Roman Empire. The Latin term, tribus has since been coined to identify a group of persons forming a community and claiming descent from a common ancestor [3]. India is the second largest country in the world, in terms of tribal population, next only to Africa. The population size of the 461 tribal groups in the country stand at 104,281,034 as per 2011 [4] census and accounts for 8.6 per cent of the total population of the country. As per the latest census data, the change in decadal growth of Schedule Tribe (ST) population during 2001-2011 is 23.7% [5]. In the context of sex ratio for the overall population (933 females per 1000 males), the sex ratio for schedule tribes is more favorable (977 females per 1000 males [5]. However, the 2001 census elicits a varying picture for the sex ratio being highest in Goa (1046) and lowest in Jammu and Kashmir (924). The average child sex ratio among tribes in India is 957 females for 1000 males. It is highest in Chhattisgarh (993) and lowest in Lakshadweep (907). Literacy rate among tribes (excluding children aged between 0-6 years) range from 59%; to 68.5% for males and 49.4% for females and it is lower than the national average of about 74%. There is a literacy gap of 19.1% between males and female members of the tribes, and it is higher in rural area (19.9%) as compared to the urban areas (12.9%). Overall literacy rate among tribes is highest in Lakshadweep (91.7%) and lowest is Andhra Pradesh (49.2%). In 1975, the Government of India initiated a project identify the most vulnerable tribal groups, as a separate category naming it as particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTG) and denoted 52 such groups. In 1993 an additional 23 groups were added to this category, making it overall a total of 75 PVTGs out of 705 Scheduled Tribes, spread over 18 states and one Union Territory (UT) in over country [4]. PVTGs are the more vulnerable clusters among the tribal groups. The states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh (AP) jointly has 33 tribal groups, boasting a head count of 4.2 million and constituting 6.31% of the total population of the above two states, whose members are located in rural areas especially in the mountainous and forest zones.

The tribes classified as primitive tribes in TS and AP are the Chenchu, Kolam, Thoti, Konda Reddi, Khond, Porja, Savara and Gadaba. These tribes largely depend on shifting cultivation and minor forest produce. The Chenchu tribes are considered to be the most PVTG as they are still largely dependent on food gathering activity for their survival. The economy of these tribes is closely associated with the ecological factors and habitats, which they live. Generally, each of their habitats is surrounded by fruit bearing trees, agricultural fields and forest. The economy of these tribes is agro-forest based and is largely a substance-based economy. From times immemorial, the tribes have led their lives in forests, isolated but keeping in harmony with their surroundings. They draw their subsistence largely from the forest produce [5]. The biodiversity of food resources that are used by the primitive tribes-the like the Chenchu, is of particular interest as they continue to live largely undisturbed by modern civilization. A general feature of the tribal population of the country is their exclusive geographical habitat. In view of their habitat and dietary habits, they stand distinguished from other population groups. Geographical isolation, primitive agricultural practices, socio-cultural taboos, poor health seeking behavior, poverty etc leads to under nutrition. Chenchu tribes are small communities with relatively low rate of population growth, compared to the other tribal populations. The documentation of the indigenous foods consumed by the Chenchu tribes and the determination of the nutrient composition of these less familiar foods are necessary for determining their nutritional status and nutrient uptake rate from the foods they consume. This also could through light on the dietary composition and maintenance of non-cultivated plant resources which could prove to be highly advantageous to nutritionally marginal populations or specifically to vulnerable groups within the tribal populations.

Chenchu Tribes

Chenchu Tribes The Chenchus belong to Hindu aboriginal tribes, residing mainly in the central hill stations of erstwhile Andhra Pradesh (AP). They inhabit the Nallamalla hill which has been a part of Nagarjuna sagar, reservoir and a Tiger sanctuary, for centuries. These tribes are labeled of the vulnerable tribal groups in 1975 by Government of India [6]. There are different and varied explanations about the origin and deravatisation of the name Chenchu. Manusmriti (Chapter 48) makes a mention of tribe Chenchu but treats the same on par with Andhras. Presumably they are the same as Chenchus of today. An ecological meaning is also attributed to the word “Chenchus” interpreting, that a person who lives under chettu (tree) is a Chenchu [7]. This legend is connected with the hindu diety Lord Mallikarjuna. Chenchus worship and believe in malevolent and benevolent deities, and follow all Hindu festivals. The major deities of Chenchus are Lord Shiva (Lingamaiah), Lakshmi Narasimhaswami, Bayyanna, Ontiveerudu, Maisammaellama, Edamma,Peddama, Pochamma, Balamma etc, are chiefly housed at the Srisailam temple. Chenchus celebrate majority of Hindu festivals. They have adopted these festivals in synonimity with people living in the planes. Their ancestors used to celebrate the Shiva ratri in parlence to the culture prevailing at the Srisailam temple to date. Monogamy is the common form of marriage among the Chenchus. Polygamy is also practiced, but rarely. Marriage is negotiated with the consent from the bride and grooms’ families. Marriage amongst cousins is common and of a preferential choice. The Chenchu tribe is broadly categorized into four local groups, that are Konda Chenchu, Koya Chenchu, Ura Chenchu and Dasari Chenchu. They are located mainly in deep forest region of combined AP. Chenchu tribes are self reliant and are trained in arts and crafts to eek out their livelihood. In physical appearance, Chenchu have features like short stature with large head, bushy eye brows and a flat nose. They converse in distinct Chenchu language with a telugu diction. Their language is termed Chenchucoolam, Chenswar or Chencharu. “Penta” is the village designate of the Chenchus. One penta is a clutch of huts housing clse kins. The village (penta) is a head nominated as “Peddamanishi’ and is generally responsible for maintaining order and harmony within the families and in the village as a whole. The Chenchu tribes have been recognized as distinct population group from the Dravidian population of south India, based on genetic mapping [8].

Population and Literacy

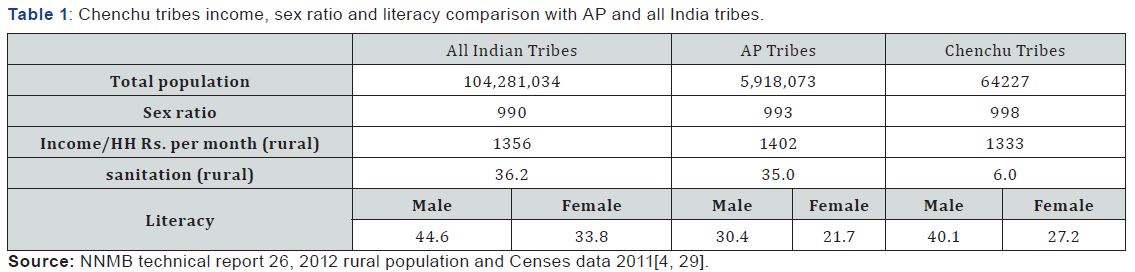

The population of Chenchu tribes in both states of AP and TS as per the 2011 census is 64227, of which the male population is 32196 and the female population is 32031. The growth rate in population has been 13% from 2001 to 2011, as the total population in 2001 was 49232. The overall literacy percentage for the Chenchu tribe stands at 40.6%, of which the male literacy id 47.3/ and that of the female is 34/. According to WHO’s World Statistics Report 2016 and Statistics report by the Union ministry of health and family welfare, Govt of India 2015 [10,11] the average life expectancy for tribes is 68 years. But, for Chenchu tribals it is below 50 years, attributable for which are excessive consumption of alcohol, smoking and severe mal nutrition problems. The data regarding income, sex ratio and sanitation levels amongst the tribal communities are indicated in Table 1.

Source: NNMB technical report 26, 2012 rural population and Censes data 2011[4, 29].

Food

The Chenchu tribes depend on forest products for their livelihood. They move in the dense forests in search of GLV, roots, fruits, and honey etc. Forest dwellers generally depend on forest produce for their food. They boil a variety of roots, tubers, leaves etc and consume them. The flesh of hunted animals is devoured upon, in roasted form. A sprinkling modest amount of salt and green chilies in accompaniment adds flavor to their routine diet. After the main course, they smoke tobacco and drink mohua liquor (Ippa sara). Indigenous bread is sometimes prepared using millets. A few studies have highlighted the fact that the chenchus are facing food shortage and poverty due to depletion of forest produce from their habitat. Even to this day around 45% of traditional thatched huts are found housing chenchu tribes, even though the government had initiated housing schemes for the rural and tribal areas [11]. Housing type can also be considered as one of the indicators of resource and economic status of the people. Nuclear types of families are predominant in Chenchu society. The average family size consists of about four members and in recent times the Chenchus have also adopted family planning methods to facilitate the “small family norm”. Food gathering, agriculture and livestock are the major sources of livelihood for the Chenchus [12].

Source: NNMB technical report 26, 2012 rural population and Censes data 2011 [4,29].

Diet & Nutrition Profile

Nutritional status of the population is one of the primary concerns of Government in developing countries and every effort is being made by them meet the food demands. However, there is an ever-increasing gap between food being produced and population growth, particularly in relevance to the third world countries [13]. From the past, our traditional diet included a wide variety of foods, and a regular maintenance of standard practices permitted adequate nutritional status, long before the current nutrition intervention program came into existence [14-18]. Central to the success of such practices was the incorporation of wild food sources, an approach used not only by traditional hunter-gatherer societies, but by pastoral and agricultural societies as well [19-22].

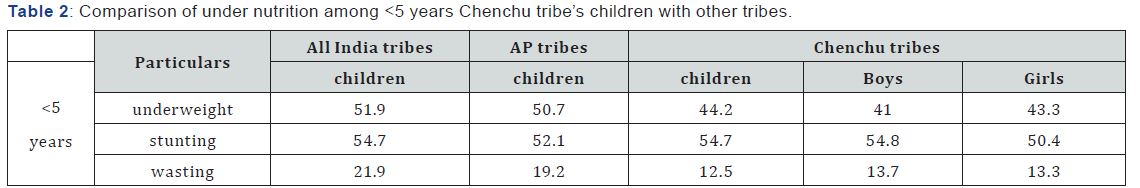

Indian tribal communities continue to remain the most nutritionally deprived social groups (in terms of procuring food from retail outlet) in the country. It is undeniable that their deprivation is influenced by a web of factors ranging from poverty and hunger due to loss of forest land and livelihood to poor re-habilitation measures, poor reach and quality of essential food and nutrition augmenting services during their critical periods of life, because of their geographical remoteness. Recent survey reports have shown that more than half of tribal children, who are under five years of age in India are stunted and wasted and failed to meet their full potential of growth and development in later life. This problem is more pronounced in Chenchu tribe’s children. It remains potentially the biggest threat to children’s growth and development. Stunted children are likely to fall ill, lag behind academically and which could eventually affect their performance and productivity, as an adult.

The National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau, of the National Institute of Nutrition (NNMB-NIN) have projected that the tribal populations are at risk of under nutrition because of their total dependence on primitive agricultural practices which is leading to an uncertainty in their food supply. Inaccessibility to even basic health care facilities and an ecological degradation further aggravates this situation. Recognizing the problem, government of India has been implementing a series of programmes under tribal sub-plan approach for the liftment of tribal population. Areas holding more than 50% tribal population are covered under Integrated Tribal Development Agency (ITDA). Chenchu tribes generally are at high risk of under nutrition owing to their dependence on primitive agricultural practices, poverty and illiteracy. Traditional beliefs and customs aggravate the situation and poor personal and environmental hygiene further compound to this already deteriorating condition along with a lagging heath care and communication facilities. To substantiate this several studies have demonstrated [23-28] that the nutritional status of tribal population is influenced by their habitat and socio-economic conditions [29].

The overall prevalence of under nutrition among below 5-year-old chenchu children can be surmised from the average scores of underweight, stunting and wasting which stands at 44.2, 54.7 and 12.5 respectively. These scores reflect the poor health status of chenchu children which is worse than the overall tribal and AP tribal scores.

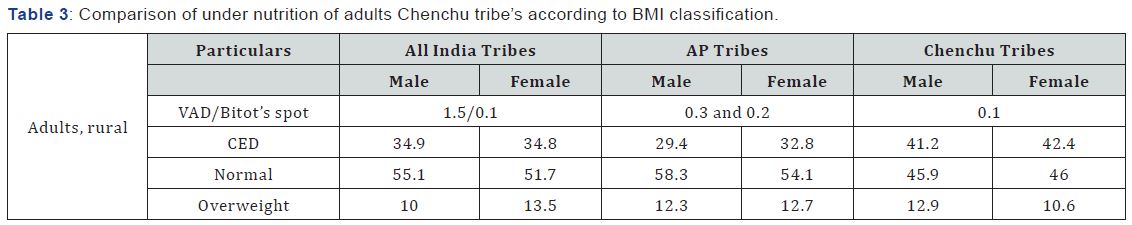

Table 3 indicates body mass index (BMI) in Chenchu tribes. About 41% of adult men and 42% of women were suffering from chronic energy deficiency (BMI<1805) while 13% and 10% were overweight/obese as per Asian cut off levels, as suggested by WHO (BMI≥23). The prevalence of CED was marginally higher among Chenchu tribes, in comparison to the other tribes in AP and all India tribes. Vitamin A deficiency was lower in these tribes when compared to AP and all India tribal population.

Source: NNMB technical report 26, 2012 rural population and Censes data 2011[4, 29].

Food Consumption Rate

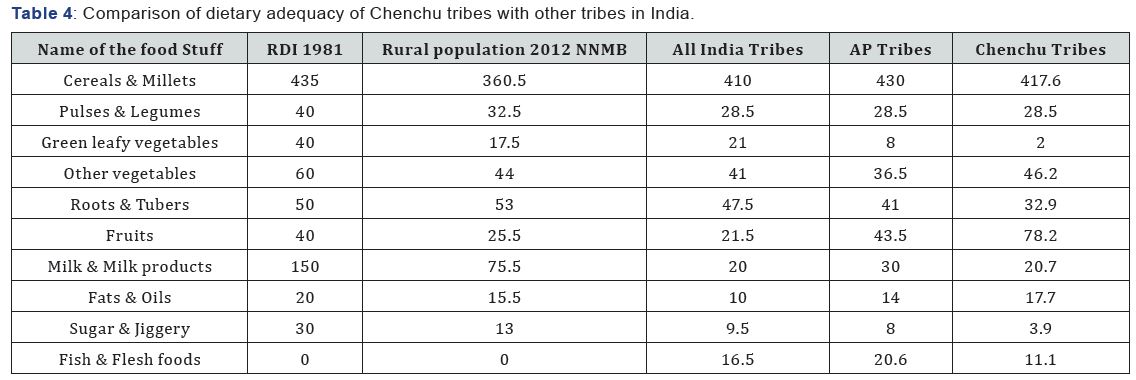

In general cereals especially, rice formed the bulk of their diet. The average intake of cereals and millets was 418/CU/ day, which was about 96 per cent of RDI intake levels. The consumption of cereals and millets was on par with that of all India tribal population’s but was lesser than the AP tribe’s consumption levels. Rural populations in general portray a lower intake of the cereals and millets. The intake of the pulses was lower (28.5g), than the recommended level (40g), as indicated in RDA. Consumption of pulses was lower than the recommended levels, in both rural and tribal populations of India. Pulses intake of Chenchu populations was similar to the intake of all India as well as AP tribal population. Contrary to the cereals, pulses intake was highest in rural populations. On the other hand, as compared to the RDI recommendation of 40g of GLV consumption, the chenchu consume a lowly (2g). Consumption of GLVs was significantly lower in all the population groups, the highest consumption being in rural population (17g). Intake of other vegetables was 46g as against the recommended 60g in Chenchu tribes. The GLV consumption of chenchu population is higher than the other population groups, such as rural, all India and AP tribes. Roots and tubers consumption stood at a disappointing level of 33gms as against the recommended levels of 50gms per day. The percent expenditure incurred for procuring roots and tubers was high, for the rural population. One of the most significant observations is that the Chenchu populations consume very high levels of fruits (78g) as against the recommended 40g per day. Except AP tribes, the rural and all India tribal populations consume for lesser levels of fruits. The average intake of milk and milk products was very low (21ml), in contrast to RDI recommendation of 150ml. Highest milk consumption was recorded for rural populations. The consumption of fats and oils was marginally lower (18g) than that factored by RDI, 20g, while on the other hand, the average intake of sugar and jaggery was only 4g, as against the recommended level of 30g (Table 4) as mentioned in the RDI.

*24 hour dietary recall. Values in parenthesis represent % intake compare to RDI [30,31].

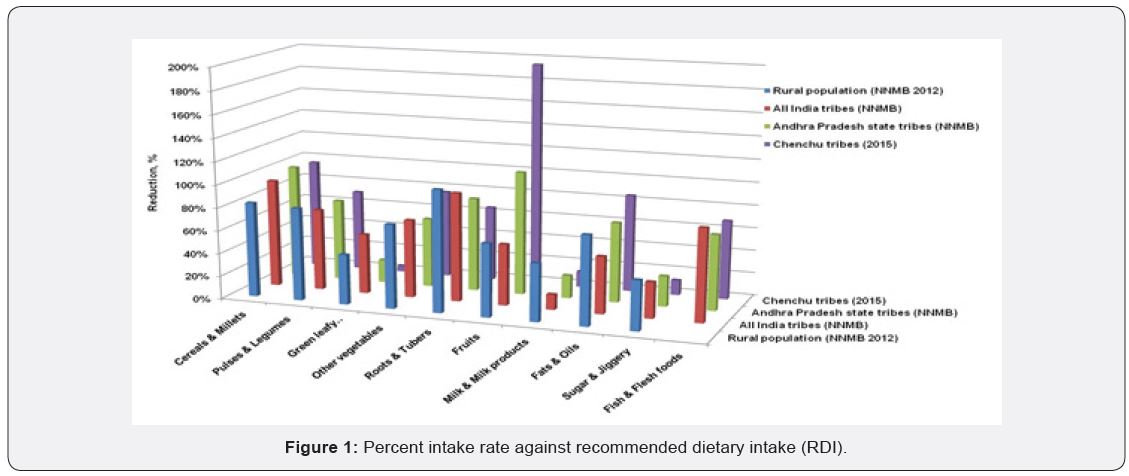

To put it in a nutshell, the chenchus diet were rich in protein and calorie uptake while being defitiant in micro nutrient. This can be deduced from there rich consumption of fruits (195%) where as GLV was at a measly 5% and roots and tubers and milk products were consumed @ of 66% and 14% respectively (Figure 1).

Nutrient Intakes

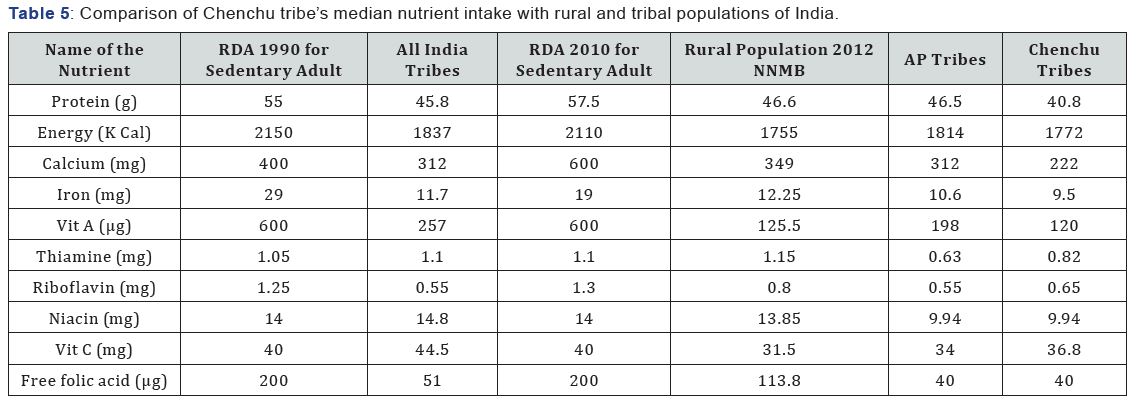

There are two recommendations for nutrient intake one published in 1990 and the other one in the year 2010. The intake of nutrients of rural, AP and Chenchu tribes is based on RDA 2010 [31] version. Based on this it was deduced that the intake of protein was the lowest in Chenchu tribes (40.8) whereas it was 46% for rural, all India tribes and AP tribal populations. The energy attained was 1772kcal as against the all India tribal energy level of at 1837kcal. The energy needed for a moderately activity tribal person is (1959kcal x1.2 CU) that is 2,351kcal/day. Similarly, for a highly active tribal person, it is (1959kcal x 1.6CU) which works out to 3,134kcal/day. Among mineral, Calcium intake was lowest among all the population groups, at 222mg/day. The highest calcium intake of 349mg/day was recorded for the rural population. Least iron intake was observed in Chenchu populations at 9.5mg/day and the highest was 11.7mg/day for all India tribal populations. The intake of B1, B2 and B3 were 0.8, 0.6 and 10mg/day, respectively. The intake of vitamin C was the highest in Chenchu tribes at 36.8mg/day, when compared to AP tribes and rural populations, attributable probably to higher fruit consumption. Intake of folates was mostly similar for all population groups and ranged from 40 mcg in Chenchu tribes to 51mcg for All India tribes (Table 5).

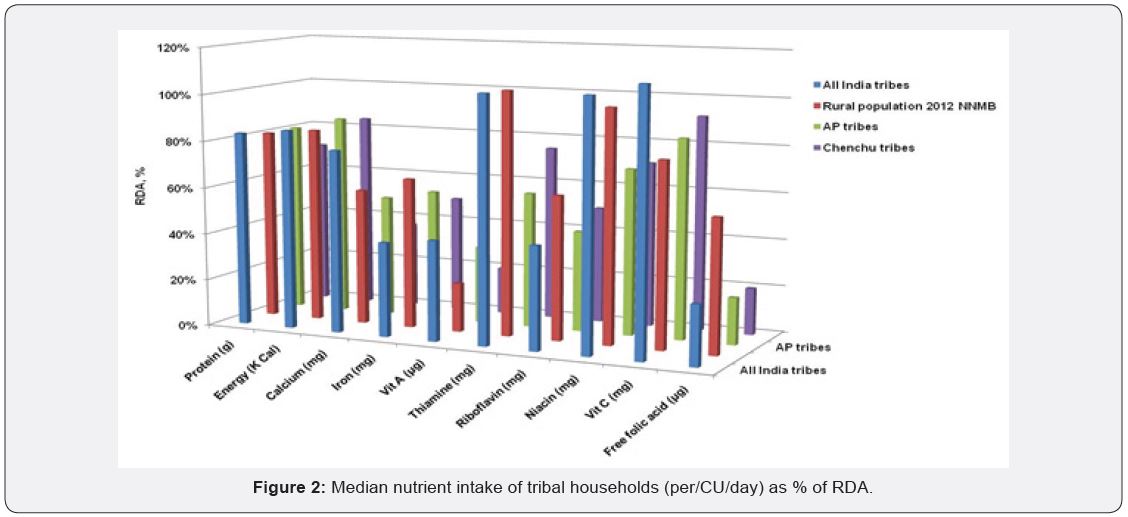

Among Chenchu population, highest nutrient intake was observed for vitamin C, at 92% of RDA followed by 75% of RDA for thiamin and 71% of RDA for protein whereas the lowest intake was 20% of RDA, for folates as well as vitamin A which was recorded. A similar pattern of nutrient intake was observed between Chenchu and AP tribes. Iron intake was lowest at 40% of RDA for all India tribal population whereas in Chenchu tribes it was 50% of RDA. Folate intake was highest in rural population of India, at 57% of RDA when compared to tribal populations, where in it ranged from 20% for Chenhu tribes to 25% for all India tribal populations. Niacin and vitamin C intakes were more than 100% of RDA for all India tribal population (Figure 2).

Calcium, niacin, vitamin C and energy were among the nutrients that were well consumed by the Chenchu populations whereas the other nutrients were below par intakes based upon 24hr dietarto that prescribed in the RDA, recall methods. The nutrient intake rates of chenchus were comparable to the nutrient intake of AP tribes because of the close geographical proximity. Lytle et al. [32] have observed that among both the genders of youth belonging to any race/ethnicity of tribals, nutrient intakes were sufficient except for total fat and saturated fat, whereas the sodium intake consistently exceeded the recommended levels. The metabolically important minerals such as calcium and iron intake were very less, in comparison to RDA levels, particularly among girls. Howe varies with time, season and the food availability. Essentially for Chenchu tribe’s, nutrition intervention as well as education are important for switching over to healthy foods. In contrast with general population the levels of calcium in pregnant and lactating chenchu women was only 50% of the RDA limits. In an earlier study, it was coated that in almost 90% of the population of chenchus, the dietary intake of protein was less than sufficient regardless of gender or socioeconomic status [33]. Rao et al. [34] have conducted a study on the nutritional status of adolescent population from different tribal areas of India and found that the consumption of pulses, milk, oils & fats as well as sugar and jaggery was lesser than the recommended levels. Only green lefy vegetables met the adequate levels of consumption in comparision to other foods which was less than adequate. The intake of important nutrients such as iron vitamin A was also not sufficient to meet the metabolic requirements. A similar pattern of food and nutrient intake was observed in the present comparative evaluation also. There seems to be very few studies on the food consumption and nutrient levels among tribal populations.

Struggle for Survival and Sustainability

In the ancient days the Chenchu tribes faced no problems regarding food security. Currently they are facing large scale problems of food insecurity and poverty due to deforestation and environment degradation which is resulting in depletion of forest resources. At present their habitat is not facilitating good nourishment, otherwise referred to as ecology of malnutrition. A large majority of population among the vulnerable groups are struggling hard to seek out their livelihood. The ecology in which those groups live is not supporting even their basic needs. These groups completely depend on forest and its natural resources. But with the depletion of these life supporting systems, they face severe crisis in regard to food. Food crisis is predominantly prevalent in the interior Chenchu occupied regions. Forest and forest produce are important resources for the Chenchus to sustain their life. Many Chenchus have been forced out of their wandering and food-gathering habit by the growing number of peasant farmers. At present the Chenchu are in a transitional stage, from food gatherers to food producers, thanks to sustained government intervention programs. Moreover, degradation of forest lands in Nallmalai hills also has a bearing on the livelihood of the Chenchus.

Prevalence of under Nutrition in Chenchu Tribes

The Chenchu tribes are facing severe under nutrition and malnutrition problems in relevance to the other tribes in India. The reasons for higher prevalence of under nutrition may be due to poverty, and consequent under nutrition, lack of awareness, access to and utilization of the available resources like GLV and forest related products which are high in nutrient content, social barriers which prevent their utilization of available nutrition supplementation program and services, poor environmental sanitation and lack of safe drinking water, leading to increased morbidity, which are associated with water-borne infections, favorable environmental conditions that promote vector-borne diseases and lack of access to health care facilities resulting in increased severity and /or duration of illnesses and death.

Conclusion

The wild plants are a main source of food and medicine for marginally surviving communities particularly for tribal people including Chenchu tribes. These plant foods possess rich nutrients and medicinal values. The livelihood of Chenchu tribes does not depend only on the agricultural and animal products but also on natural resources such as plants and the forest produce. Getachew et al. [35]. have shown that noncereal plant foods from forests as well as from agricultural and non-agricultural places, contribute significantly to the diet supplement of local residents in Africa. These wild plants provide health benefits as well as nutritive values. This is not totally a novel concept for even in ancient times, people added spices to their diet not only to impart color, taste or flavor but also for their health benefits and for their immuno protective nature. A functional food is one which not only serves to provide nutrition but also can be a source for prevention and cure of various diseases. Such functional foods are currently termed food supplements or nutraceuticals. They are inexpensive, easy to cook and are a rich source of macro and micro nutrients. Regular consumption of vegetables is also recommended for better health and management of chronic diseases. Limited fabrication and productivity of conventional crops, recurrent food deficits, and higher prevalence of macro and micronutrient insufficiency with recuring cases of chronic diseases, make diversification of food sources a worthwhile endeavor wherein wild edible plants contribute to a large and significant proportion. Tribal people consume wild edible plants which are a source of their food, income and are potentially anabolic food. Foods consumed by tribal population have been a subject of interest since antiquity, with more recent investigations being focused on their evident health benefits. In fact these foods can be used as a good source of energy and nutrition to alleviate hunger and malnutrition in tribal population.

Malnutrition continues to be a persistent public health problem in India and being well pronounced among the Scheduled Tribes of the country. While the indicators of under nutrition among the Chenchu tribes in combined Andhra Pradesh, are far behind the country’s average figures and are much lower than the national averages, of other tribal populations. With a wide cultural diversity among tribes, like in AP, efforts to identify food taboos and addressing the same through ICDS support systems, may help in the long run to bridge the nutrition deficiency gaps in Chenchu tribal community. There is an immediate need to eradicate malnutrition problems, while providing the sufficient recommended dietary foods, safe drinking water and educate them towards health and sanitation.

Acknowledgement

The author(s) are grateful to Commissioner of Tribal Welfare, Hyderabad, Government of Telangana for financial support and encouragement to collect the primitive tribe Chenchu information.

References

- Ahmed Aijazuddin, Social Geography (2008) New Delhi, Rawat Publication: 123.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Preamble to Constitution of WHO (1948) Official Record of WHO, New York, USA, 2: 100.

- Fried, Morton (1975) The Notion of Tribe Menlo Park, CA: Cummings Publishing Company, USA.

- Registrar General of India (2011) Census New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General and Census Commission, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, India.

- Government of India (1982) The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order 19.

- Government of India (1985 & 1990) The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order.

- Aiyappan, Ayyappan A (1948) A Report on the Socio-Economic Conditions of the Aboriginal Tribes of the Province of Madras. Madras: 148.

- David Reich, Kumarasamy Thangaraj, Nick Patterson, Alkes L. Price, Lalji Singh (2009) Reconstructing Indian population history, nature 461(7263): 489-494.

- World Health Organization (WHO)’s World Statistics Report (2016).

- Statistics Report (2015) Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India.

- David L Fried, Differential angle of arrival (2006) Theory, evaluation, and measurement feasibility 1975. Radio Journal, an AGU Journal forest right act (FRA) 10 (1): 71-76.

- Appalanaidu P (2013) Life and livelihood strategies among the Chenchu: forest related tribal group (frtg) in andhra pradesh. National monthly refereed journal of research in arts & education 2(7).

- Food and Agricultural Organization (1987) Promoting under-exploited food plants in Africa. A brief for policy makers. Nutrition Programs Service. Food Policy and Nutrition Division. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Jelliffee DB, Woodburn J, Bennet, FJ, Jelliffee GFP (1962) The children of Hadza hunters, Journal of Pediatrics 60: 907-913.

- Woodburn J (1968) An introduction to Hadza ecology. In: Lee RB, Ide Vore (Eds) Man the hunter Aldine, Chicago, pp. 49-55.

- Silberbauer GB, The G/Wi Bushman (1972) In Bicchieri MB (Ed) Hunters and Gatherers today. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York, USA, pp. 271-325.

- Korte J (1973) Health and nutrition. In: Chambers R, Morris J (Eds). Mwea an Irrigated Rice Settlement in Kenya, Welfform Verlag. Munich, pp. 245-272.

- Newman JL (1975) Dimensions of the Sandawe diet. Ecol Food Nutr 4: 33-39.

- Richards AI, Widdowson EM (1936) A dietary study in North-Eastern Rhodesia. Africa 9(2): 166-196.

- Beemer H (1939) Notes on the diet of the Swazi in the protectorate. Banta Stud 13: 199-136.

- Quin PJ (1959) Foods and Feeding habits of the Pedi, with special reference to identification, classification, preparation and nutritive value of the respective foods. Wit water sr and University Press, Johannesburg.

- Scudder T (1971) Gathering among African Woodland Savannah Cultivators. A case study. The Gwembe Tonga, University of Zambia, Institute Series, Zambian papers, Number 5, Lusaka.

- National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB) (2009) Diet and Nutritional status of tribal population and prevalence of hypertension among adults- Report as second repeat survey. NNMB Technical Report no. 25. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition.

- Rao DH, Rao KM (1994) Levels of malnutrition and socio-1. Economic conditions among Maria Gonds. J Hum Ecol 5: 185-190.

- Rao DH, Brahmam GNV, Rao KM, Reddy Ch G, Rao NP (1996) Nutrition profile of certain Indian tribes. In: Samal PK (Ed). Proceedings of the National Seminar on Tribal Development 1996. May 22-24, Nainital: Gyanodaya Prakasham.

- Rao DH, Rao KM, Radhaiah G, Rao NP (1994) Nutritional status of 3. Tribal preschool children in three ecological zones of Madhya Pradesh. Indian Pediatr 31(6): 635-640.

- Rao KM, Kumar RH, Venkaiah K, Brahmam GN (2006) Nutritional status of 5. Status of Saharia - a primitive tribe of Rajasthan, J Hum Ecol 19(2): 117-123.

- Mallikharjuna Rao K, Hari Kumar R, Sreerama Krishna K, Bhaskar V, Laxmaiah A (2015) Diet & nutrition profile of Chenchu population - a vulnerable tribe in Telangana & Andhra Pradesh, India. Indian J Med Res 141: 688-696.

- National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB) (2012) Diet and Nutritional status of rural population, prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among adults and infant and young child feeding practices-Report as third repeat survey. NNMB Technical Report. 26. Hyderabad, National Institute of Nutrition.

- NNMB Technical Report No.20 (2000) Special Report revised on diet and nutritional status of adolescents, elderly and food and nutrient intakes of individuals. National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research (NIN-ICMR).

- Indian Council of Medical Research, National Institute of Nutrition (ICMR- NIN) (2010) Nutrient Requirements and Dietary Allowances for Indians. A Report of the Expert Group of the Indian Council of Medical Research, National Institute of Nutrition.

- Leslie A Lytle, Himes JH, Henry A Feldman, Yang MH (2002) Nutrient intake over time in a multi-ethnic sample of youth. Public Health Nutrition 5(2): 319-328.

- Mahajan K, Ramaswami B, Caste (2015) Female Labour Supply and the Gender Wage Gap in India: Boserup Revisited. Paper presented at the International Conference of Agricultural Economists. Conference, Milan, Italy, pp. 9-14.

- Kodavanti Mallikharjuna Rao, Nagalla Balakrishna, Avula Laxmaiah, Ginnela NV Brahmam (2006) Diet and nutritional status of adolescent tribal population in 9 states of India. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 15(1): 64-71.

- Getachew Addis, Asfaw Z, Singh V, Woldu Z Baidu-Forson JJ, Bhattacharya S (2013) Dietary values of wild and semi-wild edible plants in southern Ethiopiam. African Journal of food, Agriculture Nutrition and Development 13(2): 7485-7503.