Status of Institutional Arrangements for Managing Resource Use Conflicts among Crop Farmers and Pastoralists in Imo State, Nigeria

Chikaire JU1*, Ajaero JO1, Ibe MN1, Orusha JO2 and Onogu B2

1 Department of Agricultural Extension, Federal University of Technology, Nigeria

2 Department of Agricultural Science Education, Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Nigeria

Submission: November 08, 2018; Published: December 10, 2018

*Corresponding author: Chikaire Jonadab Ubochioma, Department of Agricultural Extension, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria.

How to cite this article: Chikaire J, Ajaero J, Ibe M, Onogu B. Status of Institutional Arrangements for Managing Resource Use Conflicts among Crop Farmers and Pastoralists in Imo State, Nigeria. Agri Res& Tech: Open Access J. 2018; 19(1): 556077. DOI: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2018.19.556077

Abstract

This study ascertained the institutions put in place to manage conflicts between crop farmers and pastoralists in Imo State, Nigeria. Specifically, the study aimed to achieve the following objectives; to identify the institutions saddled with the responsibility of managing conflicts in the study area; determine strategies used by the institutions in managing conflicts in the area; and to ascertain factors hindering the management of conflicts between crop farmers and pastoralists. Data were collected with structured questionnaire, complimented with observation and oral interview from 300 crop farmers and 40 nomads. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistical tools such as mean and standard deviations. The results showed that traditional rulers (M=2.90 for crop farmers and 2.37 for pastoralists), town unions/Miyetti-Allah (M=2.11 crop farmers and M=2.52 for the pastoralists) were efficient in managing conflicts. The strategies employed in resolving conflicts include setting up of community committees for peaceful resolution of conflict issues and use of dialogue, accommodation of the other party. On and off nature of the pastoralists, lack of fund, corruption, distrust were factors that work against conflict resolution. The government should give the institutions mentioned earlier more powers in handling conflict issues and locate the nomads permanently at a place.

Keywords: Socio-economic; Conflicts; Crop farmers; Pastoralists; Land use; Land tenure

Introduction

In Nigeria’s ethnically and religiously diverse regions, violent conflict between pastoralists and farmers arises from disputes over the use of resources such as farmland, grazing areas, stock routes, and water points for both animals and households. A range of factors underlie these disputes, including increased competition for land (potentially driven in part by desertification, climate change, and population growth), lack of clarity around the demarcation of pasture and stock routes, and the breakdown of traditional relationships and formal agreements between pastoralists and farmers. Because livelihood strategies in Nigeria are closely tied to identity and because access to services and opportunities can vary across identity groups, many farmer-pastoralist conflicts take on ethnic and religious hues and are exacerbated along identity lines [1].

Fundamentally, conflict is a part of life. Social conflict can be broadly defined as the opposition between individuals and groups on the basis of competing interests, different identities, and/or differing attitudes [2]. Social conflict is not limited to the more violent or confrontational forms of opposition. Violence may or may not be involved, though violence is often one of the subjects of special interest. Social conflict is not necessarily bad as commonly portrayed. Conflict is so fully part of all forms of society that we should appreciate its importance-for stimulating new thoughts, promoting social change, provoking policy change, for defining our group relationships, and for helping us from our own senses of personal identity. Conflict with another group often leads to the mobilization of the energies of group members and hence increased cohesion of the group. Having a right attitude to social conflict is therefore necessary for conflict resolution.

Farmer-herder conflict is an enduring feature of social life in the Sahelian zone. The phrase “farmer-herder conflict” is typically used to refer to conflict between herding and farming groups. The use of this phrase can be highly misleading since it can suggest that “herders” and “farmers” are separate groups when in fact most herders are nowadays farmers and many farmers may herd their livestock at least on seasonal basis. Moreover, the conflict between a “herder” and “farmer” often implicate other farmers and herders on both sides of the conflict.

Understanding farmer-herder relations is a key to conflict resolution or management. This will help our understanding of the proximate and underlying causes of conflict, the behavioral patterns that are most conducive to provoking or avoiding conflict and the main mechanisms by which conflict between the groups are resolved or managed. The relationships between farmers and herders in the Sahelian region of West Africa have always been multi-dimensional and like most social relationships have involved both cooperation and conflict [3]. There has always been a strong seasonality to this relationship with conflicts associated with crop damage and field encroachment onto key pastoral sites common during the rainy season while cooperative relationships of milk barter and manure contracting are more important during the dry season [4].

Over the past twenty years, there have been changes in livestock ownership and management that have worked to increase both the inherent conflicts of interest between farming and herding and the potential for these conflicts of interest to escalate to degenerative conflict in many parts of the Sahelian region [3]. Conflicts of interest have intensified in many areas due to the greater proximity of livestock and cropping during the growing season due to a number of reasons, including:

a. Movements of people and shifts of livestock toward the south where rainfall is more dependable and agricultural pressure is greater;

b. A shift of livestock away from historic livestock managers along with a growing dependence on farming by pastoral people, has contributed to a reduction in the seasonal mobility of livestock herds.

Bujhra [5], observes that nomads’/farmers’ conflicts are common and widespread in Africa. For example, in Karamajoug of Uganda and the Pokot of Kenya, fighting over grazing land and cattle has existed for more than three decades. Tonah [6], reported that there is a consensus among observers that farmersherders clashes have since the 20th century become widespread in coastal countries of West Africa. He asserts that the southward movement of pastoral herds into the sub-humid zones accounts for the increasing farmers’/herders’ conflicts in Nigeria. This promotes the successful control of the menace posed by disease, the widespread availability of veterinary medicine and the expansions of farming activities into areas that hitherto served as pasture land.

Thus, pastoralists and crop farmers are intertwined sharing land, water, fodder and other resources. As a result, there are several problems which affect the relationship between farmers and pastoralists. The most outstanding being the perennial conflict over resource use. For example, in the two major livestock corridors of Nigeria (the North-West and North-East) conflicts between crop farmers and pastoralists have become particularly acute in recent years. It has been a recurring social problem for many decades but in recent years, the activities of pastoralists who move with arms usually in large groups and who commit intentional damage has added another dimension to the conflict [7].

The land resource conflicts that occur in Nigeria are always between the Fulbe or Fulani, the largest nomadic pastoral group in the world, and the indigenous settler farmers [8]. This type of conflict is found predominantly in the savanna. In Nigeria, for example, it is more prevalent in the Sudan Savanna and Guinea Savanna. Competition –driven conflicts between arable crop farmers and cattle herdsmen have become common occurrences in many parts of Nigeria. In a newspaper study of crisis in Nigeria between 1991 and February 2005, Fasona and Omojola [9], noted that conflicts over agricultural land use between farmers and herdsmen accounted for 35 percent of all reported crises. Politico–religious and ethnic clashes occurred at lower frequencies. Another study of 27 communities in North central Nigeria showed that over 40% of the households surveyed had experienced agricultural land related conflicts, with respondents recalling conflicts that were as far back as 1965 and as recent as 2005 [10]. De Haan [11], observed that no less than twenty villages were involved in farmer- herdsmen conflicts annually in some States of Nigeria, such as Kano, Oyo, Delta, Benue and many more. Nyong and Fiki’s [10], study found a spatial differentiation in conflicts occurrence, as more violent conflicts took place more frequently in resource- rich areas like the fadama (flood plains) and river valleys than resource-poor areas.

The threat to human security occasioned by these conflicts is quite true and real as cases of farmer- pastoralists conflicts abound and are widespread. For instance, in Densina Local Government of Adamawa State, 28 people were feared killed, about 2500 farmers were displaced and rendered homeless in the hostility between cattle readers and farmers in the host community in July 2005 [12]. Nweze [13], stated that many farmers and herders have lost many lives and herds, while others have experienced dwindling productivity in their herds. The cattle herds men are now being found in the South- the Guinea Savannah and forest belts in search of pasture for their herds [14].

Ajuwon [15], reported farmer – herdsmen conflict in Imo State, Southeast Nigeria. He noted that between 1996-2003, nineteen (19) people died and forty-two (42) injured in the rising incident of farmers–herders conflicts and the violence that often accompanies such conflict is an issue that can be regarded as being of national concern. These conflicts are threats to both peace and national stability. Again, in a study carried out in Nigeria’s Guinea Savannah, Fiki and Lee [16], reported that out of 150 households interviewed, 22 reported loss of a whole farm of standing crops, 41 reported losses of livestock, while eight households from either side reported loss of human lives. Their study also indicated that stores, barns, residences and household items were destroyed in many of the violent clashes. Serious health hazards are also introduced when cattle are made to use water bodies that serve rural communities.

The implications of all these may put question marks on the achievability of the 10% growth rate in the agricultural sector and its total transformation being proposed by the Federal Government of Nigeria [17]. Therefore, major sources of conflicts between the pastoralists and crop farmers show that land -related issues, especially over grazing fields, account for the highest percentage of the conflicts. In other words, struggles over the control of economically viable lands cause more tensions and violent conflicts among communities [17]. As pastoralists and cultivators have co-existed for a long time, the complexities over the land use system have dramatically changed, and thus become the major variable in conflicts between herdsmen and farmers [18]. Properly managed conflict can improve group outcomes [19- 21]. Conflicts over land develop prior to war, continue through war, and often reemerge to threaten peace building in the postconflict period [22].

In the recent past, a number of developments have occurred to suggest environmental change and social consequences affecting Nigerian small-scale producers both in the northern and southern parts of Nigeria. In the first place, herdsmen, rather than maintain the transit orientation areas, appear to be turning sedentary in the south. The newly found tendency to establish permanent and semi – permanent camps come at the cost of conflict with their farming hosts. Conflicts between herders and southern farmers seem to be increasing in frequency from the northern part down to the southern part. Conflicts are promoted by destruction of farm crops and increasingly long stay of herders in the south at times, through the southern pre-harvest rainy season that is supposedly pest infested. Today, the herder markets in the south are no longer simply places where cattle exchange hands but have now turned into major grazing bases. They also become havens protecting pastoralists against irate crop farmers. In the northern and western parts of Nigeria, studies on conflicts involving pastoralists and farmers have been carried out and reported on many occasions [15-17,23]. In the eastern part of the country, there exists a gap in understanding the institutions involved in managing conflict between pastoralists and farmers, even though there is heavy presence of the herder in every state of the Southeast. It is however unfortunate that despite the heavy presence of these nomads in south-east, little or nothing is known about the conflict resolution and management measures taken during the conflict with the host farmers. Because there are limited empirical data on this, most of the information available are based on guesses, suppositions or in literature based on occurrences from other parts of the country or world. These have given rise to wide gap in knowledge, which has inhibited effective policy formulation for solving the re-occurring conflict situations in the area. The above situation therefore raises the following research questions: What are the institutions and, strategies for managing the conflicts? The broad objective of the study was to examine effectiveness of the institutions involved in managing crop farmers and pastoralists agricultural land-use conflicts in Imo State Nigeria. The specific objectives were to:

a. Identify and analyze effectiveness of the institutions for managing conflicts in the study area.

b. Examine strategies employed for managing conflicts between crop farmers and pastoralists in the study area.

c. Identify perceived factors militating against conflict management in the study area.

Methodology

Imo State lies within latitudes 4°45’N and 7°15’N, and longitude 6°50’E and 7°25’E with an area of around 5,100sq km. It is bordered by Abia State on the East, by the River Niger and Delta State on the west, by Anambra State to the north and Rivers State to the south. The state is rich in natural resources including crude oil, natural gas, lead and zinc. Economically exploitable flora like the Iroko, Mahogany, Obeche, Bamboo, lush green grasses (which attracts the herdsmen), rubber tree and oil palm predominate the State [24,25]. Rainy season begins in April and lasts until October with annual rainfall varying from 1,500mm to 2,200mm (60 to 80 inches [24]. An average annual temperature above 20 °C (68.0 °F) creates an annual relative humidity of 75%, with humidity reaching 90% in the rainy season. The dry season experiences two months of Harmattan from late December to late February [24]. The hottest months are between January and March. The estimated population is 4.8 million and the population density varies from 230-1,400 people per square kilometer. Both primary and secondary data sources were used. The primary data were collected through questionnaire complimented with oral discussion. Descriptive statistical tools such as mean and standard deviation were used to achieve all the objectives of the study. The multi-stage (3-stage) sampling technique was adopted in the process of sample selection. The first stage was the purposive selection of three areas in the state where cases of farmerpastoralists conflicts have occurred and were reported. Here, Ohaji/Egbema, Owerri West, and Okigwe Local Government Areas were selected since conflicts occurrences have been recorded and reported widely. The second stage involved the purposive selection of the communities where these conflicts occurred. Here, Awarra and Umuapu (Ohaji/Egbema), Irete (Owerri West) and Ihube (Okigwe) communities were selected. The third stage involved the proportionate selection of 105 crop farmers from a total of 1050 affected farmers from Awara, 69 crop farmers from a total of 695 crop farmers from Umuapu and a selection of 63 affected crop farmers from a total of 630 affected farmers from Ihube and 63 farmers from 630 farmers from Irete. This gave a sample size of 300 crop farmers selected from the household lists of 3,005 crop farmers affected by the conflicts and all 40 pastoralists contained in the list of pastoralists in Imo State were purposively sampled. The household heads included widows who fend for themselves and family.

Again, mean was also computed for objectives 1 and 2 which looked at conflict management institutions and strategies using a list of 7 category institutions and 16 item statements on a 3 points Likert type rating scale of very effective, effective and not effective assigned values of 3,2,1. The values were added and divided by 3 to obtain a discriminating mean value of 2.0. Any value with mean equal to or greater than 2.0 was considered very effective and vice versa. Mean was also computed on the factors militating against conflict management (objective 3) using a 13 item statements on a 3 points Likert type rating scale of very serious, serious and not serious assigned weights of 3, 2 and 1. The values were added and divided by 3 to obtain a mean value of 2.0. Any value with mean equal to or greater than 2.0 was considered very serious and mean values less than 2.0 was considered not serious.

Results and Discussion

Institutions for managing conflict in the study area

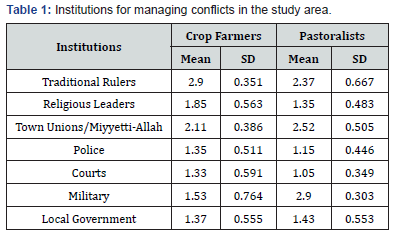

Table 1 reveals the arbitrators in crop farmers and pastoralists conflict. Traditional rulers are the major arbitrators of conflict involving crop farmers and pastoralists in the study areas. The crop farmers and pastoralists agreed that traditional rulers serve as arbitrators with mean responses of 2.90 and 2.27 respectively. Associations and unions are also conflict arbitrators as shown in the group responses. To the crop farmers town unions (¯x = 2.11) get involved in settling conflicts between crop farmers and pastoralists. The pastoralists on the other hand agreed that the Miyyeti-Allah, (¯x=2.52) are efficient also in handling conflicts. The Miyyeti-Allah is an association of herders and herd owners with branches all over the 36 states in Nigeria. Finally, the pastoralists prefer the military to settle mutual conflict as shown by a mean response of 2.90.

Mean= 2.0 Effective

nomads around South east are serfs working for highly placed traditional rulers, politicians and serving or retired military men. The big men own the large herds of cattle which they handed over to the rearer whom they placed on salary or certain terms of settlement. It was learnt that there was a mass death of cattle in North Africa between the early 1930s and 1950s which left the traditional farmers (nomads) with no cow. To keep them on course in their livelihood activity, wealthy individuals in the Northern regions purchased herds of cattle for the near poor and out- ofbusiness nomads and re-enacted them to their normal lives. So, each time conflict between crop farmers and nomads break out, the nomads run to their master (military) for protection. These masters as well have network of activities all over the federation for protection of their interest dead or alive.

The above agrees with Akinnaso [26], who posited that a close look at the herdsmen encountered on roadways and farming villages shows that they are largely uneducated young men, some of them looking haggard and spent. None of them owns the cattle they tend. They are hired laborer’s, often unrelated to the cattle owners. Whatever stipend they may be getting for their job, some of them look forward to the number of heads of cattle they may be rewarded with by their employers at the end of the day. To worsen their situation, they are now armed with guns, not just any gun, but AK-47 and other military grade weapons [26].

Viewed against the dictates of modern society and the entitlement to education by the state, nomadic pastoralism in Nigeria today is fast becoming a form of enslavement, a condemnation of youths and adolescents to an itinerant life with cows, leading to virtual dissociation from day-to-day social interaction in human society. As a result, nomads are hardly exposed to formal education and the norms of behavior in a fast-changing world. They have come to know more about cows than they know about other human beings. As a result, they put a greater value on cows than on human life [26].

Again, it could also be noted that informal traditional mechanisms for conflict resolution are still functional in the zone. Both crop farmers and pastoralist have preference for the arbitration. The desire for sustaining relationships is the major factor that informed farmers and pastoralist preference for informal settlement rather than court or police because their mutual relationship could be worsened. By traditional institutions, we refer to the indigenous political arrangements whereby leaders with proven track records are appointed and installed in line with the provisions of their native laws and customs [27]. The essence of the institutions is to preserve the customs and traditions of the people and to manage conflicts arising among or between members of the community by the instrumentality of laws and customs of the people.

From the interview conducted, traditional institutions in the Nigerian context is inclusive of the chiefs-council, elders-in-council, title holders who may be appointed based on their contributions to the growth and development of their communities with no executive, legislative or judicial powers. In African traditional setting, just as it is obtainable too in the Nigerian communities, the traditional institutions are charged with legislative, executive and judicial functions. They make laws, execute them and interpret and apply the fundamental laws, customs and traditions of the people for the smooth running of their communities. Conflicts are usually managed and resolved based on the customs and traditions of the people. Traditional institutions have different approaches to conflict management and resolution, depending on the community. What is suitable in one community may not be in another. Boege [28], agrees with this position when he argued that traditional approaches vary considerably from society to society, from region to region, from community to community. He further affirms that there are as many different traditional approaches to conflict management as there are different societies and communities with a specific history, a specific culture and specific custom even in the global south just like any other. He states that traditional approaches are always context specific and are not universally applicable as modern or conventional methods are. The traditional approaches to conflict management and resolution vary from community to community, especially when viewed against the background of diverse ethnic groups making up the region.

In the same vein, Umar [29], in a study on conflict management in Zamfara State, Nigeria noted that forty percent of the farmers and 30.7% of the herders engaged in conflicts reported that village heads were the major arbitrators of disputes involving farmers and herders in the study area. Farmers neighboring crop fields where farmer-herder disputes occur also play some role in arbitration. However, involvement of dispute resolution institutions of police and courts of law was found to be very low. This shows that informal traditional mechanisms for conflict resolution are still functional in Zamfara and that crop farmers and herders have preference for them over formal authorities when it comes to the issue of conflict arbitration. The desire for sustaining relationships is the major factor that informed farmers’ and herders’ preference. Both have the view that taking disputes to formal authorities like the police and courts of law worsens relationship between disputants.

Gbenda [30], in his own view says in traditional societies, many conflicts are resolved without calling the police. Some of the reasons for this are the intimidating size of the formal courts as compared with informal places used for resolving neighborhood conflicts. Disputants, therefore, often take their cases to elders and neighborhood mediators who can be depended upon to resolve matters in a local language, using familiar standards of behavior. The administration of justice in traditional societies was aimed at resolving conflict rather than pronouncing judgment and imposing punishment. Emphasis was placed on reconciliation and the restoration of social harmony, rather than on punishment of the people involved in the conflicts. The administration was an open-air affair, where all adults freely participated and the parties in conflict were freely cross-examined. Truth was the yardstick of the delivery of justice.

Crop farmers/pastoralists conflict resolution strategies

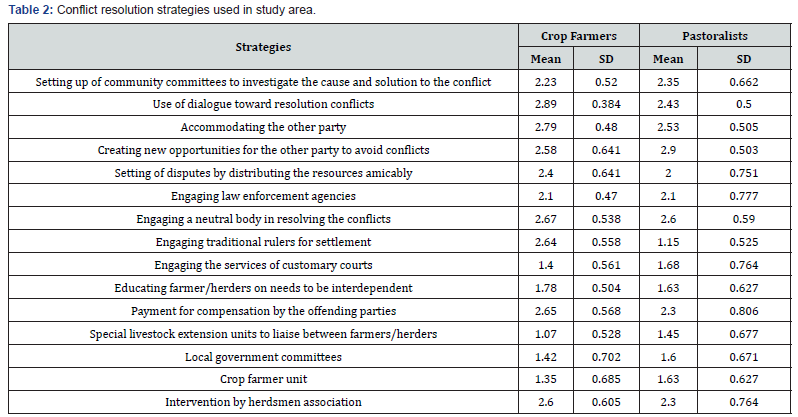

Table 2 shows the various conflict resolution strategies employed during the conflict. There are eight (8) strategies both groups indicated to be effective in resolving the conflict based on 2.0 discriminating index. These strategies include setting up of community committees for peaceful resolution of conflict issues((X) ̅=2.23 farmers and X ̅=2.35 for pastoralists),use of dialogue accommodation of the other party (X ̅=2.7 for crop farmers and X ̅=2.53 for the pastoralists, creation of opportunities to avoid conflicts (X ̅=2.58, farmers X ̅=2.90 for the pastoralists), amicable distribution of resources ((X) ̅=2.40 for crop farmers and X ̅=2.0 for the pastoralists), engaging a neutral bodies to resolve conflict (X ̅=2.67for crop farmer and X ̅=2.60 for pastoralists), payment of compensation by the offending party (X ̅=2.65 for crop farmers and X ̅=2.38 pastoralists), intervention by crop farmers/herdsman associations (X ̅=2.60 for crop farmers and X ̅=2.30 pastoralists). Other strategies include, engaging the law enforcement agencies especially the military (X ̅=2.10 for the pastoralists), engaging traditional rulers (X ̅=2.64 for the crop farmers). All these are beautiful avenues for peaceful co-existence because both parties maintained that it is only through dialogue and constructive cooperation that much desired peace could be achieved.

Mean = 2.00 and above as Effective.

Supporting the above findings, Olaoba [31], opined that the methods of resolving conflict in the traditional African societies are as follows: mediation which involves non-coercive intervention of the mediators(s) called third party either to reduce or go beyond or bring conflict to peaceful settlement. Olaoba [31], described mediation as a method of conflict resolution that had been so critical of traditional society. The mediators usually endeavour to see that peace and harmony reigned supreme in the society at whatever level of mediation. Mediators are sought from within the communities or societies of the parties concerned. Elders are predominantly respected as trustworthy mediators all over Africa, because of their accumulated experiences and wisdom. Their roles depend on traditions, circumstances and personalities, accordingly. These roles include, pressurizing, making recommendations, giving assessments, conveying suggestions on behalf of the parties, emphasizing relevant norms and rules, envisaging the situation if agreement is not reached, or repeating of the agreement already attained [32]. Adjudication in traditional African society involves bringing all disputants in the conflict to a meeting usually in the chambers or compounds of family heads, quarter heads and palace court as the case maybe [31]. Reconciliation is the most significant aspect of conflict resolution. It is the end product of adjudication. After the disputants have been persuaded to end the dispute, peace was restored. This restoration of peace and harmony is always anchored on the principle of compromise by both parties. This idea buttresses the idea of the disputing parties to give concessions [33], in negotiation the secret is to harmonize the interests of the parties concerned”. Thus, even when the conflict involves a member against his or her society, there is an emphasis on recuperation and reinsertion of errant member back into their place in society.

Factors militating against conflict management in study area

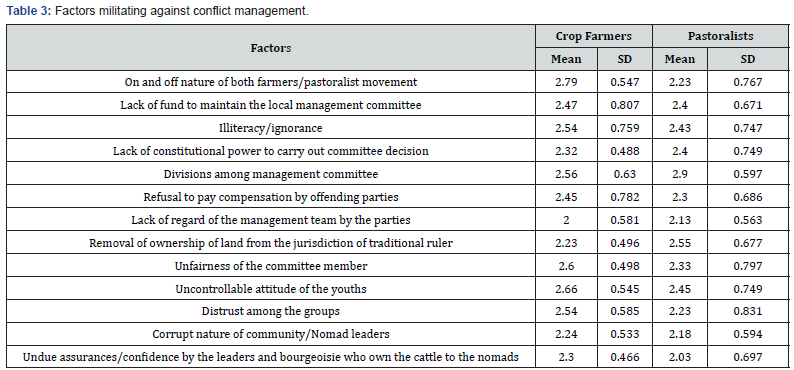

Table 3 showed that in attempts to resolve and manage conflicts by the various institutions of government there are challenges hindering peaceful and quick conflict resolution and management in the study area. There are 13 listed items of such challenges and both groups agreed that all militate against conflict resolution and management. These factors included; on and off nature of both farmers and pastoralist movement with mean responses of 2.79 for the crop farmers and 2.23 for the pastoralists. Lack of fund to maintain the conflict management committee had mean responses of 2.47 for the crop farmers and 2.40 for the pastoralists. Lack of constitutional powers on the part of the various peace committees (X ̅=2.33) for crop farmers, (X ̅=2.40) for the pastoralists. Other factors included illiteracy/ignorance with mean score of 2.54 for crop farmers, and 2.43 for pastoralists, division among committee members with mean of 2.56 for the crop farmers and 2.90 for the pastoralists, lack of regard for the conflict resolution management team (X ̅=2.0 for the crop farmers and X ̅=2.13 for the pastoralists) among so many militating factors.

Mean = 2.0 and above Very serious.

The above reveals the inadequate capacity of the local institutions to completely handle conflict situation. For this, Mwamfupe [34], said the influx of livestock into the areas which were once dominated by crop cultivators has contributed to the occurrence and persistence of conflicts between farmers and herders. At village level, the traditional conflict resolution machinery has been weakened partly by the emergence of statutory approaches based on formal procedures, and on the other hand, by the influx of herders who do not share the values and beliefs upon which these mechanisms were anchored. In sub-Saharan Africa, it has been also noted that land conflicts are proving more difficult to solve because traditional instruments of conciliation, such as compromise and consensus are failing. On the one hand, local institutions have largely lost their authority, and on the other, few institutional innovations have been developed [35]. In Kenya, resolving resource use conflicts at village level falls under the responsibility of the Village Environmental Committees composed of both farmers and herders. In situations where these committees fail, then the cases are referred to next bodies in the hierarchy. It was revealed that none of the members of the committees had received any form of training on conflict resolution skills such as mediation and negotiations. In a number of places in Kenya, the local institutions, such as the Village Environmental Committees, village governments and district machinery have shown that they lack capacity to resolve conflicts. This explains why only a small proportion of the conflicts are resolved at this level. Murithi [36], noted that inadequacy of capacity of local institutions to resolve the farmer-herder conflicts is further compounded by the mistrust that exists between the conflicting parties. On the other hand, the farmers too do not trust district level officials whom they accuse to favour the herders. District level officials always favour the herders because the livestock is a new source of revenue, and in some ways these officials may have full knowledge on the actual owners of part of the livestock herds. In this way [36], these officials work with full orders from high ranking politicians who may also own part of the livestock, and thus contributing to the arrogance of the herders”. Two things are evident in this hierarchical process of resolving the conflicts. First, local institutions lack capacity in terms of negotiating and mediation skills that are important in conflict resolutions. Second, both the herders and farmers do not trust the local institutions, both at village and district levels, and this partly explains the reluctance to cooperate in resolving the conflicts [37-39].

Conclusion

To ensure peaceful co-existence traditional rulers, town unions, herder unions, religious organizations and law enforcement agents should play reconciliatory roles. Government at all levels should empower the above organs to handle effectively resource use conflicts. However, peaceful settlement should be brought through mediation, reconciliation, negotiation, dialogue and accommodation. It was also indicated that off and on nature of nomad’s movement hindered quick conflict resolution, division among peace party members, distrust, and corruption.

References

- Mercy Corps (2016) The Economic Costs of Conflict and The Benefits Of Peace: Effects of Farmer-Pastoralist Conflict in Nigeria’s Middle Belt on State, Sector, and National Economies.

- Schellenberg JA (1996) Conflict resolution theory, research and practice. State University of New York press, USA, pp. 260.

- Turner MD (2003) Multiple holders of multiple stakes: the multilayered politics of agro-pastoral resource management in semi-arid Africa: in rangelands in the new millennium: Proceedings of the 6th International Rangelands Congress. Document Transformation Technologies, South Africa.

- Turner MD (1999) Conflict, environmental change, and social institution in dryland Africa: limitations of the community resources management approach. Society and Natural Resources 12(7): 643-657.

- Bujhra A (2000) African conflicts: their causes and their political and social environment. Paper presented at the Economies of Civil Conflicts in Africa, held at the UNECA Addis Ababa, 7th - 5th April.

- Tonah S (2006) Managing farmer- herder conflicts in Ghana and Volta Basin. Ibadan. Journal of Social Sciences 40(1): 152-178.

- Shettima AG, Tar UA (2008) Farmer-pastoralist conflict in west africa exploring the causes and consequence. Information Society and Justice 1(2): 168-184

- Kaplan RD (1994) The coming Anarchy: how crime, over population, tribalism and rapidly destroys the social fabric of our plant. In the Atlantic Monthly Journal (273): 44-65.

- Fasona MJ, Omojola AS (2005) Climate change, human security and communal clashes in Nigeria. Paper at International workshop in Human security and climate change. Holmen Fjord Hotel, Oslo, pp. 21- 23.

- Nyong A, Fiki E (2005) Drought and Conflict in the West African Sahel: Developing Conflict Management Strategies. Human security and climatic change. International workshop Oslo, Norway, USA.

- De Haan C (2002) Nigeria second fadama development project. Project preparation Mission Report, Livestock component, World Bank.

- Ofuoku AU, Isife BI (2009) Causes, effects and resolution of farmers nomadic cattle herder conflicts in Delta State, Nigeria. Agricultural tropical et subtropical 1(2): 47-54.

- Nweze NJ (2005) Minimizing farmers herder conflicts in fadama areas through local development plans. Implications for increased crop livestock productivity in Nigeria. Paper prepared at the 30th Annual Conference of the Nigeria Society for Animal Production 20th -24th March. p. 12-20.

- Oyesola DB (2000) Training needs for improving income generating activities of agro-pastoral women in Ogun State, Nigeria. Unpublished PhD thesis Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, University of Ibadan.

- Ajuwon SS (2004) Case study conflict in fadama communities in managing conflict in community development session 5. Community Driven Development. National Fadama Office, Abuja, pp.10-15.

- Fiki C, Lee B (2004) Conflict generation conflicts management and selforganizing capabilities in drought prone rural communities in North eastern Nigeria: A Case Study. Journal of Social Development in Africa 19(2): 25-48.

- Isah MA (2012) No retreat, no surrender: conflicts for survival between fulani pastoralists and farmers in Northern Nigeria. European Scientific Journal 8(1): 331-346.

- Rahim MA (2002) Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict. The International Journal of Conflict Management 13(3): 206-235.

- Alper S, Tjosvold D, Law KS (2000) Conflict management, efficacy, and performance in organizational teams. Personnel Psychology 53(3): 625-642.

- Bodtke AM, Jameson JK (2001) Emotion in conflict formation and its transformation: Application to organizational conflict management. The International Journal of Conflict Management 12(3): 259-275.

- Kuhn T, Poole MS (2000) Do conflict management styles affect group decision making? Human Communication Research 26(4): 558-590.

- De Church LA, Marks MA (2001) Maximizing the benefits of task conflict: The role of conflict management. The International Journal of Conflict Management 12(1): 4-22.

- Gefu JO, Kolawole A (2002) Conflicts in common property resources use experience from an irrigation project. Paper prepared for the 9th conference of the International Association for the study of Common Property. Indiana USA.

- Imo State Government (IMSG) (2010) Examination ethics commission, ministry of education, Owerri. Government Printers, Nigeria.

- National Population Commission (NPC) (2006) Official Population Report of South East Nigeria.

- Akinnaso N (2018) The Dark Side of Nomadic Pastoralism in Nigeria today.

- Orji KE, Olali ST (2010) Traditional institutions and their dividing roles in contemporary Nigeria. In: Babawale T, Alao A, et al. (Eds.), The Rivers State Experience. The chieftaincy institution in Nigeria, concept publishing united Lagos.

- Boege V (2006) Traditional approaches to conflict transformation: potentials and limits. Bergh of research centered for constructive conflict management. p. 21.

- Umar FB (2010) The Pastoral-Agricultural Conflicts in Zamfara state, Nigeria. North- central Regional center for Rural Development, Iowa State University. USA.

- Gbenda J (2010) Age-long land conflicts in Nigeria: a case for tradition peacemaking mechanisms. Journal of Conflict Transformation 1(1-2): 156-176.

- Olaoba OB (2005) Traditional Approaches to conflict Resolution in the South-West zone of Nigeria. Nigerian Army Quarterly Journal 7: 22-37.

- Brock-Utne B (2001) Indigenous Conflict Resolution in Africa. A Draft presented to a week-end seminar on indigenous solutions to conflicts held at the university of Oslo, Institute of Educational Research. 23rd and 24th February. p. 16.

- Williams ZI (2000) Traditional cures for modern conflict. Africa conflict medians. Lynee Reinhart Publishers.

- Mwamfupe D (2015) Persistence of farmer-herder conflicts in Tanzania. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 5(2): 1-8.

- Kirk M (1999) The context for Livestock and crop-livestock Development in Africa: the evolving role of the state in influencing property Rights over Grazing Resources in sub-saharan Africa. In: McCarthy N, Swaltoer B, et al. (Eds.), Property Rights, Risks, and livestock Development in Africa. IFPRI/ILRI.

- Murithi T (2006) Practical peacemaking wisdom from Africa: reflections on Ubuntu. The Journal of Pan African Studies 1(4): 25-34.

- Bennett O (1991) Green war: environmental and conflict. Panos Institute, London, UK.

- Breusers M, Dederlof S, Rheanen T (1998) Conflict or symbiosis? Disentangling farmer-herdsmen relations: The Moss, and Fulbe of the Central Plateau, Burkina Faso. Journal of Modern African studies 36(3): 357-380.

- Nwagwu WE, Opeyemi S (2015) ICT Use in Livestock Innovation Chain in Ibadan City in Nigeria. Advances in Life Science and Technology 32: 29-44.