Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Lignocellulosic Agricultural Wastes to Fermentable glucose

Rusudan Khvedelidze*, Nino Tsiklauri, Lali Kutateladze, Tina Sadunishvili, Zura Darbaidze and Giorgi Kvesitadze

Agricultural University of Georgia, S. Durmishidze Institute of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Georgia

Submission: August 30, 2018; Published: September 21, 2018

*Corresponding author: Rusudan Khvedelidze, Durmishidze Institute of Biochemistry and Biotechnology of Agricultural University of Georgia, David Aghmashenebeli ave, Tbilisi, 0159, Georgia; Tel: 995599345990; Email: r.khvedelidze@agruni.edu.ge

How to cite this article: Rusudan K, Nino T, Tinatin A, Edisher K, Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Lignocellulosic Agricultural Wastes to Fermentable glucose. Agri Res & Tech :Open Access J. 2018; 17(5): 556042. DOI: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2018.17.556042

Abstract

S. Durmishidze Institute of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, strains isolated from different ecological niches of Southern Caucasus – active producers of carbohydrolases have been selected by means of screening under deep cultivation conditions. Among this strains are producers of carbohydrolases-cellulases, amylases, proteases, xylanases. Thermophilic micromycetes from the collection of microscopic fungi active strain producers of extracellular cellulases, has been selected. Hydrolytic potential of cellulase preparations isolated from the selected strains has been investigated according tohydrolysis of cellulose in agricultural wastes. The wastes have been pretreated biologically (by basidial fungi) and thermo-mechanically (2 atm, at 140°C, for1 hour). During 10-days of basidial fungi cultivation more than 50% of lignin was utilized from wheat straw, corn stubble, rice straw an potato straw. The following enzymatic treatment of biologically fermented substrates was converted from 54 to 85% of cellulose to glucose. These data are comparable and sometimes even exceed the analogous data of previously used thermo-mechanical pretreatment of substrates.

Keywords:Microscopic fungi; White-rot fungi; Thermopile; Hydrolysis; Pretreatment

Abbrevations: SSF: Solid-State Fermentation; DNS: Dinitrosalicylic Acid; ABTS: 2,2-azino-bis-[3-ethylthiazoline-6-sulfonate]

Introduction

Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose in lignocellulosic biomasses to fermentable glucose is the most important technological processes among all possible enzyme technologies. The cost of ethanol production based on current technologies from lignocellulosic materials is relatively high, and the main challenges are the low yield and high price of the hydrolysis process. Considerable research efforts have been made to improve the hydrolysis process of lignocellulosic materials. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials to remove lignin and hemicellulose can significantly enhance the deepness of cellulose hydrolysis. The lignin acts as a barrier to enzyme and microbial penetration in lignocellolose substrates significantly decreasing the yields of fermentable sugars; it negatively affects the overall process of hydrolysis most often making it uneconomical [1].

The multi enzymatic lignicellulose degradation is quite complicated process. There are several enzymes acting simultaneously, such as: laccase, oxidizing phenol ring containing compounds by forming phenoxy radicals and quinones; cellulases and xylanase perfoming -endo and -exo type hydrolysis of cellulose and xylan. Laccase, actively participating in lignocellulose hydrolyses process, is one of the most versatile enzymes, which can find application in many different industrial sectors [2,3].

To overcome this limitation, some physical, chemical and biological pretreatment of the lignocellulose are used for effective cellulose hydrolysis [4,5]. Enzymes, hydrolyzing and oxidizing these biopolymers are found in plants [6-8], but the equilibrium of their hydrolysis and/or oxidative degradation is so strongly shifted toward their synthesis that hydrolysis becomes negligible process and should not be taken into consideration. For successful industrial realization of cellulose enzymatic hydrolysis in addition to high specific activity of enzymes from mycelyal fungi, up to now recognized as the best producers of enzymes (cellulases/xylanases/laccase), some other characteristics of enzymes are required: heat-resistance under the high temperature regimen (60-65 °C), resistance against inhibition by terminal products of cellulose hydrolysis, deep and effective hydrolysis of different lignocellulose substrates. Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose, which is the main component of plant mass (makes above 60% of all plant mass) from the point of view of fermentable glucose and biofuel production in large scale, becomes the most important technological process among all possible enzyme technologies [9-12].

Materials and Methods

Thermo-mechanical pre-treatment

Lignocellulose substrates: wheat straw, corn straw, rice straw, potato straw. All residues were dried at 60 °C and milled to dust extent (<1mm). After the cellulosic substrate was autoclaved at 2atm (140 °C) for 1 hour.

Microscopic fungi, mediums content and inoculums preparation

Soils, plants, and thermal springs from the most hot places of western (subtropical), eastern (steppe), and southern soilclimatic zones of Georgia were used as sources for isolation of mycelial fungi strains: Mucor, Rhizopus, Chaetomium, Allescheria, Malbranchea, Botrytus, Monilia, Aspergillus, Penicillium, Sporotrichum, Trichoderma, Trichotecium, Alternaria, Cladosporium, Helmintosporium, Fusarium and the order Mycelia Sterilia. The procedure of fungi strains isolation was performed from primary plating on 8% agar containing medium. The fungi were cultivated in deep conditions at 35-55 °C for ten days. The strains were cultivated on the following nutrient mediums containing (in %):

a. Microcrystalline cellulose–1,0.

b. Corn extract–1.5.

c. NaNO3–0,3.

d. KH2PO4–0,2.

e. MgSO4×7H2O–0,05.

The strains were grown in Erlenmeyer flasks with 250 or 750ml on a shaker having 180-200 rapids/min in a 30l fermenter (New Branswick, USA).

White-rot fungi and Inoculums preparation

In The study basidial fungi strains: Ganoderma sp. GV-01, Ganoderma sp. GV 02, Ganoderma lucidum GM 04, Pseudotrametes gibbosa GG 76, Pleurotusdrynus IN 11, Pleurotusos treotus GD 41 were used. White-rot fungal inoculates were prepared by growing the fungi on a rotary shaker at 180rpm, at 27 °C in 500ml flasks containing 100ml of synthetic medium of the following composition (g/l):

a. Glucose–15.0NH 4NO3–3.0.

b. Yeast extract–3.0.

c. NaH2PO4–0.9.

d. K2HPO4–0.3.

e. MgSO4–0.5.

Initial pH was adjusted to 5.7 prior to sterilization. The nutrient medium was sterilized at 121 °C for 20min. After 7-10 days of fungi cultivation, mycelium was inoculated to conduct the solid-state fermentation (SSF) of lignocellulose containing materials [13].

Cultivation conditions

Solid-state fermentation (SSF) of selected plants residues was carried out at 27 °C in 250ml flasks containing 5g of lignocelllulosic substrates moistened with 18ml of the nutrient medium (g/l):

a. NaNO3–2.0

b. Yeast extract–3.0

c. KH2PO4–0.9

d. K2HPO4–0.3

e. MgSO4×7H2O–0.5

f. 0.2mMCuSO4×5H2O

g. pH 5.8

The flasks were inoculated with 5ml of mycelial homogenate. To determine enzyme activity, after 10 and 15days of cultivation, the extracellular enzymes were extracted from the 5g of cell biomass, which previously was washed twice with 10ml of distilled water (total volume 20ml). The extract was centrifuged at 10 000g for 15min at 4 °C. The final filtrate was used for determination of enzyme activities. Remained wet biomass was dried at 60 °C and used for hydrolysis.

Enzyme activities assay

Viscosimetric activity was determined as a result of enzyme action on soluble Na-CMC according to the method modified by Rodionova et al. [14]. Aliquots of appropriately diluted culture filtrate as enzyme source was added toWhatmanNo.1 filter paper strip (1×6cm; 50mg) immersed in one milliliter of 0.05M acetate buffer, pH 4,5. After incubation at 50 °C for 1h, the reducing sugar release was estimated by dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method [15,16]. One unit of filter paper (FPU) activity was defined as the amount of enzyme releasing 1mole of reducing sugar from filter paper per ml per min. To obtain enzyme preparation, culture liquid was precipitated by ethanol in the ratio of 1 volume liquid to 4 volumes of cold ethanol (+2-4 °C). Xylanase activity was determined by mixing 70μl appropriately diluted samples with 630μl of birch wood xylan (Roth 7500) (1% w/v) in 50mM citrate buffer (pH 5.0) at 50 °C for 10min [17]. Glucose and xylose standard curves were used to calculate cellulase and xylanase activities. In all assays, the release of reducing sugars was measured using the dinitrosalicylic acid reagent method [18]. Laccase activity was determined by monitoring the A420 change related to the rate of oxidation of 1mM 2,2-azino-bis-[3-ethylthiazoline-6-sulfonate] (ABTS) in 100mmol sodium tartrate buffer (pH 4.5). Assays were performed in 1ml spectrophotometric cuvette at 30±1 °C with adequately diluted culture liquid. One unit of laccase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme, which leads to the oxidation of 1mmol of ABTS per minute [19].

Determination of glucose

The amount of glucose was determined by glucosooxidaseperoxidase method. 3ml of glucosooxidase-peroxidase reagent was added to 0.2ml of analyzing solution. After delaying for 30minutes, the intensity of formed color was measured on spectrophotometer at 420nm of wavelength. The amount of glucose was estimated by preliminarily diagrammed calibration curve.

Results and Discussion

Mycological studies exposed the most frequently met genera in various substrates of Southern Caucasus slopes (Georgia): Mucor, Rhizopus, Chaetomium, Allescheria, Malbranchea, Botrytus, Monilia, Aspergillus, Penicillium, Sporotrichum, Trichoderma, Trichotecium, Alternaria, Cladosporium, Helmintosporium, Fusariumand the order Mycelia Sterilia. Systematic analysis revealed the existence in collection strains of Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, Zygomycetes, Deuteriomycetes, Mycelia Sterilia. Among the collection strains there were cultures growing on natural biopolymers (cellulose, xylan, lignin, starch, pectin, etc.) and producing different set of extracellular enzymes: cellulases, xylanases,laccase, Mnperoxidase, α- and glucoamylase, acid and neutral proteases, pectinases, invertase, α-galactosidase. etc.

Among the possible enzyme- based technologies the process of lignocellulose bioconversion to produce ethanol as alternative energy source, glucose fructose mixture as a sweetener, single cell protein or any other valuable products, the main problem is utilization/degradation of non-carbohydrate biopolymer lignin. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials in different ways to remove lignin and hemicellulose is widely spread significantly enhancing the deepness of cellulose sacharification to glucose [20-22]. Existence of relatively cheap biotechnology of lignin elimination remains the problem for industrial realization of lignocellulose raw materials enzymatic conversion to glucose. White-rot basidiomycetes are overall spread organisms producing lignin and cellulose-degrading enzymes, among which primarily laccase carrying out lignin degradation/utilization should be underlined [23,24].

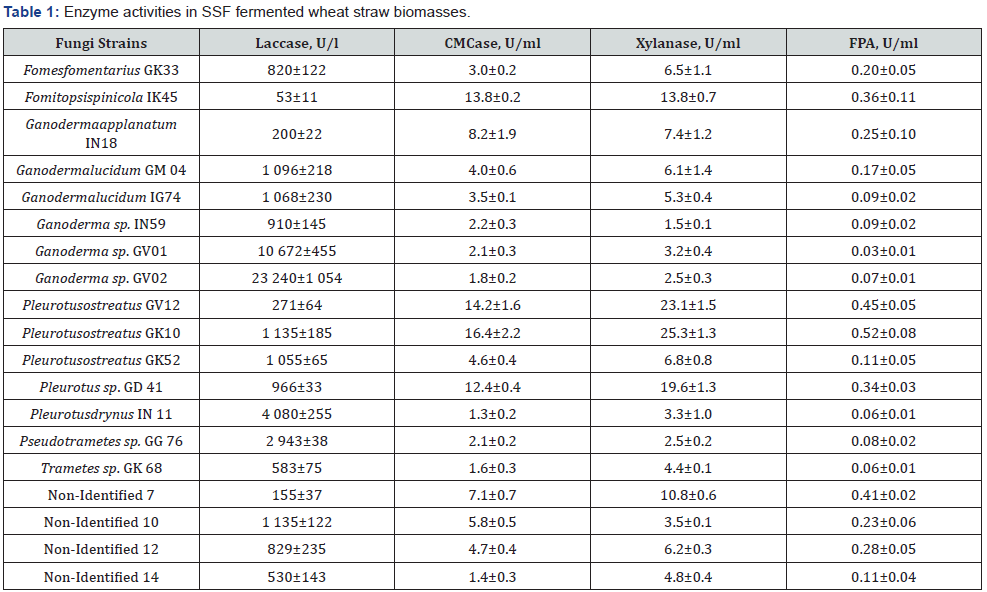

To determine basidial fungi strains potential to produce lignocellulose degrading enzymes solid-state fermentation of different genera strains on wheat straw was carried out (Table 1). Wheat straw is widely spread as substrate containing all typical lignocellulosic biopolymers: cellulose, xylan and lignin and its degradation requires existence of full set of lignocellulose degrading enzymes.

Solid state fermentation technology being the most similar to natural growth of basidial fungi is accompanied by formation of all typical enzymes required for degradation of wooden biopolymers [24]. To determine the biosynthesis potential of the selected strains enzymes (hydrolyses: CMCase, xylanase, FPA and laccase) the basidial fungi strains of different genera and families differing in lignin utilization ability were cultivated on wheat straw by solid state fermentation (SSF). Data of these experiments are presented in Table 1. As seen from the Table 1, presented the strains in various level were producing enzymes but with quite big differences. For instance, the activity of laccase in different strains was facilitating from 53 reaching 23240 units/L. The laccase was most actively produced by Ganoderma strains namely by Ganoderma sp. GV-02 and Ganoderma sp. GV-01. Such a huge difference in laccase activities of cellulose and xylan degrading enzymes indicates on wide varieties of these strains application. It is interesting to underline that the most active laccase producer strains in above experimental conditions exposed a low activities of cellulose and xylan degrading enzymes.

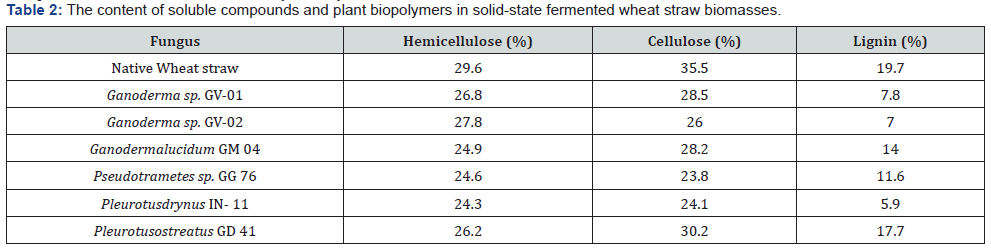

To determine the efficiency of mycelial fungi strains individual potential of lignin utilization in agro wastes, such complicated compound as wheat straw was chosen. After basidial fungi solidstate fermentation on wheat straw in final solid-state fermented biomasses, the following components were determined: soluble compounds, cellulose, lignin, and xylan. The final amounts of these components indicate on the deepness of microbial transformation of wheat straw. As it was revealed, qualitatively the amounts of these components differed final biomasses (Table 2).

First, it should be stated that basidial strains are performing the utilization of lignin in different extent. Lignin was effectively degraded by Ganoderma strains, the most active producers of laccase. The final amount of this biopolymer was in both cases less than 10% (8,8 and 9,4). In the biomass transformed by Pleurotas drynus the amount of lignin was 8.2%, so this strain most effectively transformed wheat straw lignin in fungal biomass. The efficiency of the strains in lignin elimination is around 50% of initial amount of lignin.

Several times repeated experiments showed that utilization of lignin has direct correlations with the genera of basidial fungi used. According to some literature data, the 56 in day of cultivation P. Chrysosporium degraded lignin by 41%, S. badius for by 31% [25], in other experiments the strain Phanerochaete flavidoalba decreased amount of lignin by 46% [20]. The comparison of lignin utilization efficiency of these strains, with our strains grown during only 10 days showed advantages of Ganoderma and Pleurotas representatives in the velocity of lignin utilization (Table 2). Taking into consideration that these strains insignificantly degrade cellulose and effectively utilize lignin their solid-state cultivation could be a good base for creation of completely biological delignification process.

Mycelia fungi strains extracellular cellulase activities

For the hydrolysis of cellulose in agro-wastes fifty producers of cellulases with different extracellular activities were selected from the collection of mycelial fungi collection (3500 strains). As optimal conditions, for the cultivation of selected strains were 40-45 °C, they were considered as thermotolerants, producing comparatively heat-stable forms of cellulases. According to our results to carry out the hydrolysis of cellulose to fermentable glucose in partially delignified wheat straw or other agricultural wastes, more promising seems to be cellulases from Penicilliumcanescence TK-2 and Trichodermaviride 16-3 (Table 3). In this Table 3 typical extracellular activities of the most active producers are given (Figure 1).

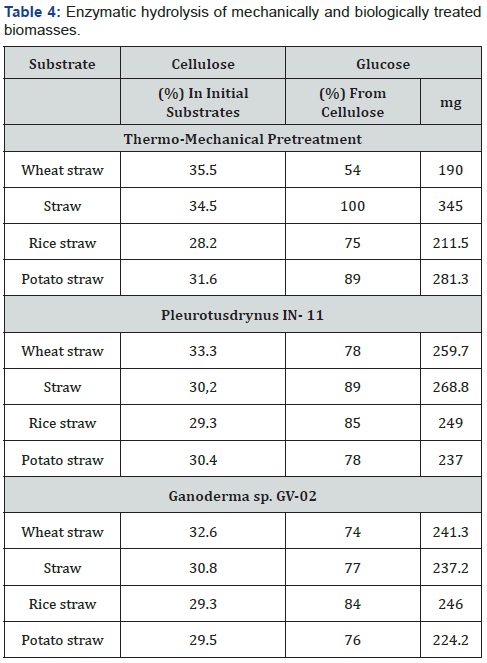

From the above presented strains (Table 3) due to the highest activity and previously estimated reasonable heat stability of cellulases the enzyme preparation from Penicilliumcanescens TK-2 was chosen. The optimal temperature of cellulases action isolated from this strain was 55 °C. The enzymatic hydrolysis of agricultural wastes was carried out in a reactor, during 24h, ambient:0.05M acetate buffer, pH 4,5. Concentration of the substrate was 50g/l, the correlation of enzyme activity units and substrate was 60CMC units per 1g of substrate. Results of enzymatic hydrolysis of thermo mechanically and biologically (by basidial fungi) pretreated substrates are presented in Table 4.

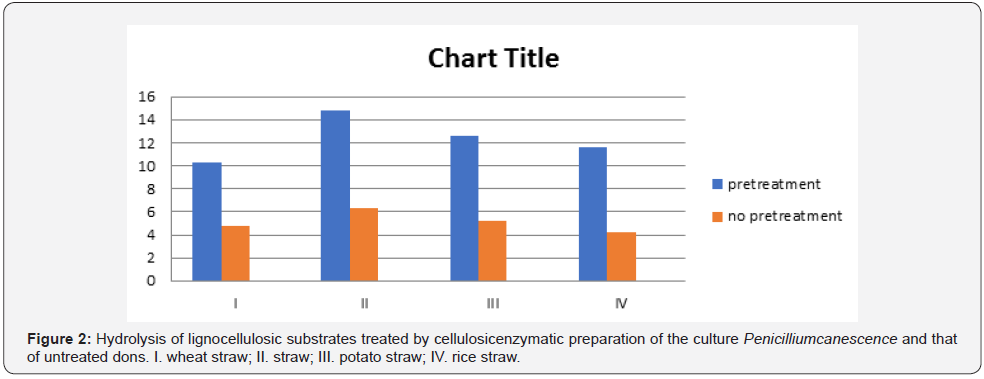

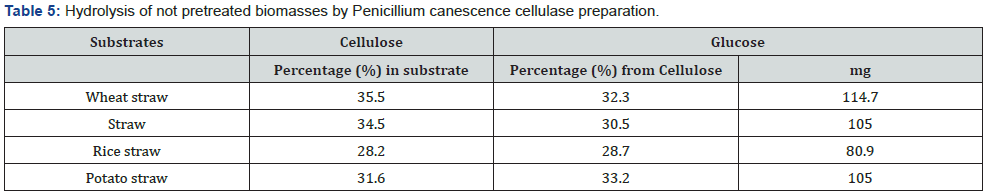

As it was previously proved by the authors, thermomechanical pretreatment of the above listed agricultural wastes is one of the most effective methods for their following enzymatic hydrolysis, sometimes allowing to reach 90-100% of substrates cellulose conversion to glucose. Therefore, this method has been chosen for the comparison with biological treatment performed by basidial fungi. According to the data presented in Table 4, Table 5 and Figure 2, pretreatment biotechnology by basidial fungi is comparable and sometimes (wheat straw and rice straw) even exceeds thermo-mechanical method in efficiency.

Conclusion

The above presented investigation aimed to select special strains of mycelial fungi for pretreatment and hydrolysis of cellulose in agricultural wastes without any physical or chemical treatment. For this reason from the collection of mycelial fungi collection kept at Durmishidze Institute of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Georgian Agrarian University, 50 previously selected strains producers of extracellular cellulases/xylanases and 21 strains of basidial fungi accumulating laccase in different extent were used. The search of needed strains with corresponding enzyme activities reveal the most active producer of cellulases strain Penicilliumcanescens TK-2 and basidial fungi strains Ganoderma sp. GV-01, Ganoderma sp. GV-02 and Pleurotusdrynus IN 11, the most active producers of laccase with low activities of cellulases. The pretreatment of cellulose containing agricultural wastes such as: wheat straw, corn straw, rice straw, potato straw by selected basidial fungi, growing in solid state conditions up to 10 days, lead to decrease of lignin in wastes for 50% or more. Agricultural wastes treated by basidial fungi much more effectively undergo the following enzymatic degradation by cellylases. Insignificant degradation of cellulose during basidial fungi processing substrates (less than 1%) should not be taken into consideration. The percent of cellulose hydrolysis to glucose for untreated agrowastes was approximately 30%, after treatment of agro-wastes by basidial fungi the percent of hydrolysis reached in average 70- 75%. Such deepness of cellulose hydrolysis to fermentable glucose is comparable and sometimes even exceeds widely used thermo mechanical or any other pretreatment of substrates.

Acknowledgment

This work was financially supported by Korea and performe dunder the ISTC contract #G-2117.

References

- Reginado A, Toni O, Wagner C (2007) Plant Physiology 19: 1013.

- Widsten P, Kandelbauer A (2008) Laccase applications in the forest products industry: A review. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 42(4): 293-307.

- Cabana H, Jones JP, Agathos S (2009) Utilization of cross‐linked laccase aggregates in a perfusion basket reactor for the continuous elimination of endocrine‐disrupting chemicals. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 102(6): 1582-1592.

- kvesitadze E, Torok T, Urushadze T, Khvedelidze R, Kutateladze L, et al. (2007) Abstract book, 2-5 July, 71-74. Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Talebnia F, Karakashev D, Angelidaki I (2010) Production of bioethanol from wheat straw: An overview on pretreatment, hydrolysis and fermentation. Bioresource Technology 101(13): 4744-4753.

- Maheshwari R, Bharadwaj G, Bhat MK (2000) Thermophilic fungi: their physiology and enzymes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64(3): 461-488.

- Hakiand G, Rakshit S (2003) Developments in industrially important thermostable enzymes: a review. Bioresour Technol 89(1): 17–34.

- Rampelotto P (2010) Resistance of Microorganisms to Extreme Environmental Conditions and Its Contribution to Astrobiology. Sustainability 2(6): 1602-1623.

- Viikari L, Alapuranen M, Puranen T, Vehmaanperä J, Siika-Aho M (2007) Thermostable enzymes in lignocellulose hydrolysis. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 108: 121-145.

- Yennamalli MR, Rader AJ, Kenny JA, Wolt DJ, Sen ZT (2013) Endoglucanases: insights into thermostability for biofuel applications. Biotechnologies for Biofuels 6(1): 136.

- Urushadze T, Khvedelidze R, Kvesitadze E (2007) Plant & Microbial enzymes: isolation, characterization & biotechnology applications, abstract book, 2-5 July: 118-122. Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Jacobsen SE, Wyman CE (2000) Cellulose and hemicellulose hydrolysis models for application to current and novel pretreatment processes. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 84(1-9): 81-96.

- Tsiklauri N, Khvedelidze R, Zakariashvili N, Aleksidze T, Bakradze- Guruli M, et al. (2014) Higher Basidial Fungi Isolated from Different Zones of Georgia – Producers of Lignocellulosic Enzymes. Bulletin Georg Natl Acad Sci 8(1): 102-108.

- Rabinovich M, Klesov A, Berezin I (1977) Bioorganic Chemistry 3: 405- 414.

- Adney B, Baker J (1996) Measurement of Cellulase Activities. Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP). p. 11.

- Klyosov A (1990) Trends in biochemistry and enzymology of cellulose degradation. Biochemistry 29(47): 10577-10585.

- Bailey MJ, Biely P, Poutanen K (1992) Interlaboratory testing of methods for assay of xylanase activity. Journal of Biotechnology 23(3): 257–270.

- Miller CL (1959) Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Analytical Chemistry 31(3): 426–428.

- Bourbonnais R, Paice MG (1990) Oxidation of non-phenolic substrates. An expanded role for laccase in lignin biodegradation. FEBS Lett 267(1): 99-102.

- Lopez M, Vargas-Garcia M, Suarez-Estrella F, Moreno J (2006) Biodelignification and humification of horticultural plant residues by fungi. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 57(1): 24–30.

- Kvesitadze G, Urushadze T, Khvedelidze R (2013) Stable Carbohydrolases of Extremophilic Mycelia Fungi. Bulletin Georg Natl Acad Sci 7(3): 92-98.

- Martinez AT, Speranza M, Ruiz-Duenas FJ, Ferreira P, Camarero S, et al. (2005) Biodegradation of lignocellulosics: microbial, chemical, and enzymatic aspects of the fungal attack of lignin. Int Microbiol 8(3): 195–204.

- Kunamneni A, Ballesteros A, J Francisco P, Alcalde (2007) Communicating Current Research and Educational Topics and Trends in Applied Microbiology by A Méndez-Vilas (Edt.). pp. 233–245.

- Shraddha, Shekher R, Sehgal S, Kamthania M, Kumar A (2011) Laccase: Microbial Sources, Production, Purification, and Potential Biotechnological Applications. Enzyme Research 2011: 11.

- Huang H, Zeng G, Tang L, Yu H, Xi X, et al. (2008) Effect of biodelignification of rice straw on humification and humus quality by Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Streptomyces badius. Biodeterioration& Biodegradation 61(4): 331–336.