Ecology, Behaviour and Conservation Status of Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus): A Comprehensive Review

Anisa Iftikhar1* and Irfan yaqoob2

1Department of Biology, Clarkson University, Potsdam, USA

2Department of Computer Science, Clarkson University, Potsdam, USA

Submission: February 16, 2024;Published: February 27, 2024

*Corresponding author: Anisa Iftikhar, Department of Biology, Clarkson University, Potsdam, USA

How to cite this article: Anisa I, Irfan y. Ecology, Behavior and Conservation Status of Ring-Necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus): A Comprehensive Review Arch Anim Poult Sci. 2024; 2(4): 555593. DOI: 10.19080/AAPS.2024.02.555593

Abstract

The common pheasant is a widespread species in the ecosystem. This review summarizes recent knowledge on the ecology, behaviour, and conservation status of this species, emphasizing adaptability, feeding habits, and social structures. Therefore, Phasianus colchicus harbours a varied conservation status across its wide distribution; it is under threat from a wide number of sources, spanning from habitat loss to hunting and changing environmental conditions. The following sections in this paper will explore these aspects as a contribution to the understanding of the ecological roles of Phasianus colchicus and contribute information that is useful for conservation aimed at mitigating threats to its survival.

Keywords: Ring-necked Pheasant; Ecology; Behaviour; Conservation status; Phasianus colchicus

Introduction

Phasianus colchicus is a common pheasant and a species of significant interest in avian ecology, conservation biology, and biodiversity studies. P. colchicus is native to Asia and has a history of distribution, ranging from subtropical to temperate zones, and extends to diverse habitats such as agricultural lands and woodlands, through its introduction from Asia to many parts across the world for hunting. The behaviour and ecology of an animal can be derived from the habitat it prefers to live in, what it feeds upon, and its social conduct. Moreover, the status of game birds accrues to their attendant economic and cultural importance, which tends to stress the balance between human interests and conservation [Davis and Thompson, 2023]. Hence, this review assimilates the available research on the ecology, behaviour, and conservation status of Phasianus colchicus, thereby identifying the complexities in its management and conservation challenges [Johnson & Kumar, 2021].

Taxonomy and Distribution

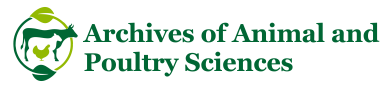

Pheasants are species of game birds and are placed in the order Galiformes, such as megapods (Megapodiidae), cracids (Cracididae), guinea fowl (Numididae), New World quails (Odontophoridae), turkeys (Meleagrididae), grouse (Tetraonidae), partridges, Old World quails, and pheasants (Phasianidae) [Delacour, 1977]. The ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus cholchicus) is a significant member of the family Phasianidae, originally native to Asia. It is popularized in the world as an eminent game bird and is the most documented species of the order Galliformes worldwide [1]. The common pheasant (Phasianus cholchicus) is a state bird found in South Dakota for economic reasons (economically). The state is well known for its ring-necked pheasant hunting, which draws thousands of out-of-state hunters and generates millions of dollars in income. The genus’s name is “Pheasant” and the species name is “P. Colchicus” [2].

There are two subfamilies: Ring Neck Pheasant, Phasianinae and Perdicinae. However, in American states, there are three types of sub family (Tetraonidae) grouse, (Numididae) Guinea fowl, and (Mela agrididea) Turkeys. The diversity study indicates that there are four groups of pheasants found in North America: (1) ring-necked pheasants in Europe, North America, and Asia; (2) white-winged pheasants of Afghanistan; (3) green pheasants in Japan; and (4) European pheasants of Eastern Europe [Sibley, 2003].

Pheasants comprise 181 species that are distributed throughout the world, of which 49 are found in Asia [2]. There are six pheasant species in Pakistan, including the Cheer, Tragopan, Himalayan Monal, Kalij, Koklas, and Indian peafowl [Saeed et al., 2017]. The Himalayan pheasant populations have been classified into five sub-species groups based on morphological variation in the male plumage. Monal (Lophophorus impeyanus), Koklas (Pucrasia macrolopha), Western Horned Tragopan (Tragopan melanocephalus), White Crested kalij (Lophora leucomalana), and Cheer (Catreus wallichii) are indigenous species of Pakistan [Andersson, 1994]. The cheer pheasant (Catreus wallichii) is a vulnerable species of the pheasant family because of the increase in habitat loss, hunting in some areas, and small population size [Birdlife International, 2014]. The population of the Western Horned Tragopan is also vulnerable and needs protection because it is considered the rarest species among all living pheasants, as per the IUCN Red List. The populations of Koklas, Kalij, and Monal are decreasing daily and need some protective measures. The major reason for this is habitat destruction in their native range; therefore, all species of pheasants are the most vulnerable and threatened. Over 1/3 of the total population is at risk of extinction in their native range [IUCN, 2006]. Figure 1 (Showing the Variable Families and Important Species in the Order Galliforme, with Particular Focus on P. colchicus). It displays the evolutionary connections between the different Galliformes species. Every branch symbolizes a distinct species, and the split ends of branches signify shared ancestry. Two species are seen as being more closely related the closer they are to one another on the tree.

Geographic Range

Phasianus colchicus is a non-migratory Eurasian species. Its native range ranges from the Caspian Sea east through Central Asia to China, including Korea, Japan, and the former Burma. It has been introduced in Europe, North America, New Zealand, Australia, and Hawaii. Phasianus colchicus populations have spread across mid-latitude agricultural lands in North America, from southern Canada to Utah, California to New England, and down to Virginia. It was first brought to the United States in 1857 and has since spread throughout the Midwest, Plains, and parts of the West [1].

Ecology

Physical Appearance

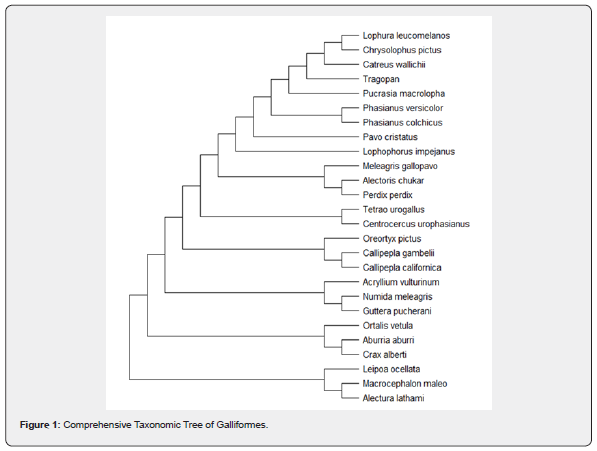

Male ring-necked pheasants are large and gaudy, with a small green head, pale bill, and red facial skin. The presence of a white collar around the thin neck makes them more distinctive from all the other subspecies. It has a very long, thin, and pointed coppery tail with black bars and spurs on its legs. Golden plumage has white and black spots throughout (lab of Cornell Ornithology, 2011). There are two ear tufts behind the face, which makes them more alert (The Observer’s Book of Birds, p.214). The weight of the male was 2.5-3 pounds. The tail length of the male was 18-26 inches. The ring-necked pheasant is dimorphic, and males are adorned with ornaments, but females are simpler and lighter in weight. Males are heavier and have colourful, brilliant plumage. A white ring is present around the neck in most males of this species. The spurs are present on the legs of pheasants and increase in size as they age. Spurs are also present on the legs of juvenile pheasants, with a length of approximately 3/8 inch. When male pheasants reach old age, spurs also start to grow on the head of the pheasant. It is approximately one inch long on an old male [2-6].

Females are short-necked with small tails, have no spurs on their legs, and have paler scaling on the upper parts. They also have Buffy brown or cinnamon heads and underparts with black spots and bars on their sides, such as the head, neck, back, and wings, and thin black bars on their pointed tail. The body plumage of males may vary between gold, purple, brown, and white, whereas females have drabbed brown feathers and are less showy. The average weight of a female is 2-2.5 pounds. Their tail length was 8-12 in. Both sexes can grow up to 10 weeks of age, but in females, 16 weeks of age is more frequent (lab of Cornell Ornithology, 2011). The chicks were slightly different from each other. They show similarities in colour with the hens during the first two months of their birth. After 8-10 weeks, they showed variations and started looking like young males. They mature within 2 months. Over time, they attain full maturity in all features within the age of 4-5 months (Farris et al., 1977). Newly hatched chicks were protected with fluffy buff-coloured down with dark markings on the head and back approximately half an ounce. They can leave their nests after some hours of hatching. They can fight for a very short time, even after birth, for 10 to 12 weeks [1] (Figure 2).

Habitat Range and Preferences

Male and female common pheasants have greater home ranges during the breeding season than in winter. During the nesting season, females tended to have larger home ranges than males did. Some chickens' wintering home ranges were reported to be 63.7 hectares in Missouri and 49.7 hectares in Maryland, respectively. In Iowa, house ranges of 76 ha and 96 ha were identified. Weather, land cover and usage, and human density have the potential to influence these variances [Flock et al., 2002]. Regarding habitat, Phasianus colchicus is very adaptable, as avian species prefer habitats that serve to provide the species with both a secure refuge away from predators and an abundance of food sources. In its native range, this species mostly occurs at the edges of forests and in meadows and along river systems. It is also adapted, in introduced territories, to show its ecological plasticity: introduced territories, to agricultural fields, orchards, and even urban fringes [Smith & Wang, 2022]. Their habitats differ in the winter and summer. For replication, a self-sufficient pheasant population requires a portion of the site to be a form of everlasting gross cover. Moreover, some populations may need to be covered to protect them from critical climatic conditions. In their populations in northern latitudes, such as North and South Dakota, the species needs woody cover to provide thermal repose to save them from critical climate situations [Perkins et al., 1997; Leif, 2005]. Increasing the daytime interval initiates multiplicative motion between the pheasants (Figure 3).

Feeding Ecology

Phasianus colchicus is omnivorous, and changes with seasonal changes in resource availability. Pheasants generally live on agricultural land and chiefly depend on minor grains and seeds distributed with continuous grass cover [1,7]. It consists of a wide array of food items including seeds, grains, fruits, insects, and small invertebrates. This dietary flexibility enables it to survive in different habitats and further reveals itself in local biodiversity through seed dispersal and predation on diverse species of insects and other small organisms [Johnson & Kumar, 2021]. The pheasant is a very flexible bird with respect to its food behaviour. The food is different in every season. However, basic foods always remain the same throughout the year. They eat seeds, grains, nuts, grasses, roots, insects, and wild fruits, but this depends on the area and seasonality of food availability [8]. Discarded grains are the normal food of pheasants, but in the winter season, they can be accessed at a limited depth of snow [1]. For their rapid growth, they must eat food rich in proteins that can come from different sources such as insects, slugs, spiders, and other vertebrates, up to six weeks of age. Seeds, plant materials, and some additional factors are the most important foods for the growth of old pheasants. They usually feed on the ground and scrape for food with their feet or bills. Although open water is not required for Phasianus colchicus, many populations are found around bodies of water. In dry environments, common pheasants obtain water from dew, insects, and succulent vegetation [1].

Ecological Role and Interaction

Phasianus colchicus is one of the prey species responsible for the sustenance of several predators at the food web level, such as mammals and raptors. Its behaviour affects the dynamics of vegetation and soil quality, contributing to the functioning of the ecosystem. The interaction of species with the environment underlines the significance of biodiversity maintenance and ecosystem services [Johnson & Kumar, 2021]. They may also spread seeds through predation. They may harm larger prairie chickens and gray partridges by parasitizing nests, competing for habitat, transmitting disease, and exhibiting aggressive behaviour [9]. Common pheasants are often released into wooded areas for shooting. A study in Britain investigated the impact of this approach. Researchers have discovered that common pheasants have a neutral or favourable impact on vegetation and bird communities [10].

Behaviour

Social Behaviour

The common pheasants are social birds. In autumn, they congregate in large numbers, sometimes in locations with food and shelter. Typically, the core home range is smaller during winter than during the nesting season. Flocks established in winter can be mixed or single-sexed with up to 50 pheasants. During the breeding season, males are usually accompanied by a harem of females [1]. Common pheasants spend most of their time on the ground and roost trees. They are fast runners that walk with a "strutting gait." While feeding, they keep their tail horizontal; while running, they hold it at a 450 angle. Common pheasants are excellent fliers that are capable of flushing nearly vertically during take-off. Males frequently release croaking calls during take-off. They flee when threatened [Johnsgard 1986]. A common pheasant dust bathe involves sweeping sand and dirt particles into their plumage with bill-raking, ground scratching, or wing shaking. This behaviour helps eliminate dead epidermal cells, excess oil, old feathers, and new feather sheaths [5]. Their cruising speed is 43-61 km/h (23-33 kn), but when being chased, they are capable of reaching speeds of up to 90 km/h (49 kn).

Reproductive Behaviour

They are polygamous, meaning that males maintain territories and strive to attract multiple females to mate. However, they did not form pair bonds. Males are adorned with bright colours, and they exhibit a complex display of courtship to win over females. Males establish mating or crowing territories throughout early spring (mid-March to early June) [1]. These territories are comparable to other male territories and may not have clear boundaries. In contrast, females did not exhibit territorial behaviour. Within their breeding harems, they may exhibit a dominance hierarchy. These harems endure throughout the courting and nesting seasons and may contain 2-18 females. Each female normally has a seasonal monogamous connection with a single territorial male [11]. Males establish harem in early spring by crowing and flapping their wings. Males employ a distinctive, loud kork-kok call to maintain their territories. A virtually inaudible wing flap may precede this, followed by a brief but powerful wing whirring by a male. Physical encounters between competing males can include flying breast-to-breast, biting wattles, or high leaps with kicks to the other's bill. Males who establish breeding territories earlier in the season are more dominant than males who do so later in the season [12]. Females choose their mates based on a variety of variables. Female common pheasants prefer dominant males, who can, for example, provide security. According to previous studies, females prefer long tails, and the length of ear tufts and the presence of black spots on the wattle also influence female preference. The overall brightness of a male's plumage is irrelevant, perhaps because brightness is unrelated to testosterone levels or dominant behaviours in male common pheasants [13]. Territorial disputes are common and may involve vocalization or actual contact [Davis & Thompson, 2023]. The study of pens indicates that the hen will continue to lay eggs for approximately three weeks based on single mating. One male can mate with approximately 50 females in one season without loss of fertility. They breed once a year [Johnsgard, 1986].

Males use various courtship displays, which evoke varying responses from females. According to one study, feeding rituals in males attracted female common pheasants, whereas lateral display wooing activities in males aroused copulation in females. In a lateral display, the male approaches the female by slowly passing a semicircle in front of her, his head down, the nearer wing drooped, and his wattle erect. This lateral display frequently precedes copulation; however, later in the season, a male may simply pursue and attempt to mount a female [1].

Nesting Behaviour

Nesting started just before the females started laying eggs. Peak incubation occurred in May and peak hatching started in mid-June. Incubation lasted approximately 23 days after the final egg was laid. In Southern Iowa, the pheasant starts nesting early in March, but the egg-laying period starts from mid to late April. The nesting and incubation periods occur only by hens, and they construct the nest. The nest is a small depression lined with erect grass and vegetative material, such as grasses and weeds, which are laid on the ground in dense cover. Its length should be at least about 8-10 inches tall. The female lays between 7 and 14 eggs, which she alone incubates. When two or more chickens lay eggs in the same nest, they produce larger clutches. When the eggs hatch, the young leave the nest nearly quickly, with the mother caring for them. While females care for the young, they feed on themselves [1,11] (Figure 4).

Lifespan

Chick survival is influenced by hatch date, birth mass, and habitat type. Many young people do not live in autumn. Adult females have an annual survival rate of 21%-46%, compared to only 7% for men. In some regions, the lower male survival rate can be attributed to hunting by common male pheasants. Almost all wild birds perish by the age of three years. Predation, agricultural operations, pesticide and toxin exposure, and motor vehicle accidents contribute to adult death rates [1,14].

Seasonal Behaviours

The behaviour of Phasianus colchicus was distinctly modified with the coming seasons. Migration does not occur frequently in this species; however, movement is known to occur because of food availability and environmental conditions. As part of its wintering behaviour, Phasianus colchicus forms loose flocks for efficient foraging and protection against predators [Davis and Thompson, 2023]. Migratory movements are evident in northern populations, where cold weather causes birds to seek warmer climates. Males leave first during group dispersal in early spring, which is progressive rather than abrupt [1].

Communication

Vocalizations are quite important for Phasianus colchicus, which is believed to be utilized for many communicative purposes, including the declaration of some sort of territory and the start of breeding. The sound repertoire encompasses crow, cackle, and alarm calls, which all refer to the corresponding type of information to conspecifics and social influence [Davis and Thompson, 2023]. The male pheasants produce sounds like “COOKS. They made harsh and loud croaking sounds when alarmed. This crowing sound is often used when males establish their territories. In agricultural settings, males can hear crowing at twilight, dawn, and during the mating season. This call is extremely close to the recognized rooster call and has a range of up to miles. Female calls are more delicate and less audible [1,12].

Economic Importance

Pheasants are important for many reasons such as recreational, aesthetic, and economic purposes. Pheasant production and shooting are the most productive businesses in developing countries [15 Pheasants are useful for humans for many purposes throughout the World. Sustainable profits can be achieved through production and management through economic inducements [15]. Pheasants have two important characteristics that make them more meaningful. First, they are the most prominent species in nature, and second, they are eye-catching and widely act as food sources [16]. They are a source of social improvement [Long 1981]. Some of these species are used to control ecosystem health [17]. In well-developed countries, the pheasant is not only a game bird but also a very productive bird. This type of industry is essential to the management and preservation of countryside zones [Grahn et al. 1993]. The ringneck pheasant has become a highly iconic symbol of cultivated Midwest landscapes, and the male pheasant proves to be an excellent quarry for sportsmen with its rapid running capacity and volatile flight [1].

Economic Importance for Humans

The most significant benefit of Phasianus colchicus in humans is that it is an upland game bird [13]. In the field of hunting, ring-necked pheasants are extremely important to human economics [18]. Because of their popularity as game birds, hunters are drawn to the area, and they support local economies through hunting license sales, taxes, and tourism [16,18]. The economic value of the Ring-necked Pheasant as a food source has also been mentioned in several sources, especially in Asia, where it is considered a delicacy.

Conservation Status

Abundant and pervasive. Although populations in their homelands are declining, those in North America are thriving, not likely due in part to regular bird stocking in places where hunting is popular. The Ring-necked Pheasant is a "Least Concern" species according to the IUCN [18], Global, 2012]. This indicates that there is currently little chance of the Ring-necked Pheasant going extinct and that the population is stable. However, habitat loss, hunting pressure, and predation pressure pose challenges to some ring-necked pheasant populations [16,18].

Threats to population viability

Species extinction is a natural process, but such a process is currently accelerated by several factors; therefore, many species of birds are on the brink of disappearance at present [19]. The decline in bird populations has resulted from habitat loss, illegal egg collection, poaching, hybridization with other species, hunting, and a spectrum of human disturbances. Such activities not only decrease the number of individuals in the wild but also hurt the reproductive success, fertility, and survival of the offspring [20].

Habitat Loss

However, there are several threats to this species. One major reason is the destruction of their habitat in their native range for different purposes, such as removing trees, producing hardwood, agricultural invasion, and excessive foraging of animals. Pheasants are mainly dependent on forests for their habitat; therefore, the removal of valuable trees in large numbers causes deforestation, which in turn affects the population of pheasant species. This commonly occurs in tropical forests where antique trees are removed for commercial purposes [15].

Hunting

Another major reason is hunting on a large scale, which hurts the population of pheasants. Adult common pheasants can be preyed upon either on the ground or during flight. Almost all members of the order Galliformes are harvested on a large scale for different purposes such as food and game trade. The reason behind this is that they are game birds, so they attract the attention of hunters. Quantitative estimation of hunting is difficult because hunting is an illegal activity. However, this has a major negative impact on the population [15]. Hunting of this species occurs for many reasons, mainly to meet the nutritional requirements, as they are a good source of protein. Another reason is that they are easy to capture and shoot, and their beautiful feathers attract hunters [21,22]. In some regions, game hunting poses a considerable risk of predation to male pheasants. Common pheasants are particularly vulnerable to predation during nesting [1].

Human Impact

Human attraction toward pheasants has always been high due to their stunning feathers, which enable them to catch or shoot easily and enrich proteins [22]. Hunters are attracted to them due to their healthy meat having low fat, enriched in necessary amino acids, and fatty acid content than broilers, including geese and ducks [23]. Approximately all species of pheasants are exploited as food sources for meat and egg requirements in natural ways throughout the world because they are easy to capture and a good source of protein. Copper pheasant is a species that is threatened by humans because it is raised under custody to arrange pheasants for games [1].

Harvesting

Along with hunting, many other factors, such as harvesting, adversely affect the pheasant population because they mainly forage on the ground, usually in the morning and evening, build nests on the ground, and are found on the ground for different activities [15]. Humans also engage in other types of activities that annoy their population. Humans produce medicines from fungi and different kinds of herbs during the spring season. This is a major agitation in the population of pheasants [Katocrakhah et al., 1997]. Advancements in the tourism industry are another disturbing factor of this kind. Hunting of pheasants on the ground is the major cause of the decrease in their population, and damage to their natural habitat is another major cause, such as poor nourishing situations and increasing hunters [Hoodles et al., 2001].

Conservation and Management Strategies

Conservation actions need to be set in place for the long-term sustainability and viability of Phasianus colchicus populations in various settings depending on population monitoring and management techniques [16], [Tuia et al., 2021]. To restore ecological balance, management strategies may include habitat conservation through land-use planning, predator control techniques such as selective culling or the introduction of natural predator habitats, education campaigns about ethical hunting methods in partnership with local communities, and regulatory bodies for sustainable wildlife harvesting [16,24] [Li et al., 2009]. This can be achieved through the creation of designated areas for these species, sustainable hunting, or agricultural environment schemes. Aspects such as public awareness and community involvement must be facilitated, which further proves the need for education and engagement [Green and Harper 2020]. Captive breeding is considered an effective solution to conserve endangered species, but it has many risks, such as the loss of genetic diversity and limited opportunities for these species to survive in their natural habitats.

To overcome these challenges, assisted reproductive technologies, such as semen cryopreservation [Iftikhar and Yaqoob, 2024] and artificial insemination (AI), have become invaluable tools. These techniques are vital for preserving genetic diversity and the transfer of useful genes to the future for their ability to rescue and multiply rare types and species that may not be bred in captivity [19]. The oldest method used today dates back to the development of glycerol as a cryoprotectant some fifty years ago [Hold & Pickard, 1999). These findings have been well documented in domesticated avian species such as chickens [25], turkeys and ducks [26]. Thus, these conservation techniques need to be effectively applied to save species because of the decreasing population of ring-necked pheasants.

Conclusion

Future studies and conservation initiatives for Ring-necked Pheasants should focus on several important areas. Additional research and monitoring are required to determine the current conservation status of pheasant populations and to detect any population decrease or localized extinctions [Li et al] [27-36]. Second, to manage and restore the habitats of Ring-necked Pheasants in various places, research should focus on understanding the biological and unique habitat requirements of these birds [16], [Li et al., 2009]. Moreover, effective management of P. colchicus for proper conservation would have to address most of the challenges faced by birds. Future research should focus on the effects of climate change, habitat connectivity, and genetic diversity on the population dynamics. It is also through collaboration between conservationists, policymakers, and local communities that sustainable solutions can be effectively identified, developed, and implemented [Green & Harper, 2020]. A literature review of the ecology, behaviour, and conservation challenges facing the species has highlighted the need for informed, collaborative management approaches. As anthropogenic activity continues to change natural habitats, it is imperative that the degree of resiliency in species, as exemplified by Phasianus colchicus, be understood for the betterment of biodiversity and ecosystem health [Johnson & Kumar, 2021; Smith & Wang, 2022].

References

- Giudice J, Ratti J (2001) The Birds of North America Online. Ring-necked Pheasant.

- Mcgowan PJ (1994) Display dispersion and micro-habitat use by the Malaysian peacock pheasant Polyplectron malacense in Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Tropical Ecology 10(2): 229-244.

- Saeed A, Rehman AU, Ahmed S, Awais M, Mahmood T, et al. (2017) Evaluation of Mortality Rate of Three Captive Pheasant Species at Dhodial Pheasantry, Mansehra, Pakistan 12(2).

- Andersson M Sexual selection: Princeton University Press (1994).

- Flock BE, Applegate RD (2002) Comparison of trapping methods for ring-necked pheasants in North-Central Kansas. North American Bird Bander 27(1): 2.

- Perkins AL, Clark WR, Riley TZ, & Vohs PA (1997) Effects of landscape and weather on winter survival of ring-necked pheasant hens. The Journal of wildlife management 634-644.

- Geaumont BA (2009) Evaluation of ring-necked pheasant and duck production on post-Conservation Reserve Program grasslands in southwest North Dakota. North Dakota State University, Fargo, US.

- Hill D, Robertson P (1988) Breeding success of wild and hand-reared ring-necked pheasants. J Wildlife Management 52(3): 446-450.

- Hagen CA, Jamison BE, Robel RJ, Applegate RD (2002) Ring-necked pheasant parasitism of lesser prairie-chicken nests in Kansas. The Wilson Bulletin 114(4): 522-524.

- Aldous EW, Alexander DJ (2008) Newcastle disease in pheasants (Phasianus colchicus): a review. The Veterinary Journal 175(2): 181-185.

- Johnsgard PA (1986) The pheasants of the world. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Johnsgard PA (1975) North American game birds of upland and shoreline. University of Nebraska Press, US.

- Greenberg R (2002) Ring-necked Pheasant. In J Greenberg, J Hamilton, eds. Birds of Canada. Kyodo, Dorling Kindersley, Singapore pp. 185.

- Martin PA, Ohnson DL, Forsyth DJ (1996) Effects of grasshopper‐control insecticides on survival and brain acetylcholinesterase of pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) Environ Toxicol Chem 15(4): 518-524.

- Fuller RA, Garson PJ Edts (2000). Pheasants: status survey and conservation action plan 2000-2004.

- McGowan PJ, Ding C, Kaul R (1999) Protected areas and the conservation of grouse, partridges and pheasants in east Asia. Animal Conservation 2(2): 93-102.

- Ashraf S (2015) Studies on Growth Performance, Morphology, Reproductive Traits and Behavioural Aspects of Ring Necked Pheasants In Captivity (Doctoral Dissertation, University Of Veterinary And Animal Sciences Lahore, Pakistan).

- Zhou C, Xu J, Zhang Z (2014) Dramatic decline of the Vulnerable Reeves's pheasant<i>Syrmaticus reevesii</i>, endemic to central China. Oryx 49(3): 529-534.

- Rakha BA, Hussain I, Akhter S, Ullah N, Andrabi SM, et al. (2013) Evaluation of Tris–citric acid, skim milk and sodium citrate extenders for liquid storage of Punjab Urial (Ovis vignei punjabiensis) spermatozoa. Reproductive biology 13(3): 238-242.

- Subhani A, Awan MS, Anwar M (2010) Population status and distribution pattern of red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus murghi) in Deva Vatala National Park, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan: a pioneer study. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 42(6).

- Howman K (1993) Pheasants of the world: their breeding and management: Hancock House Publishers Ltd.

- International B (2012) IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Choice Reviews Online 49(12): 49-6872.

- Strakova E, Suchý P, Vitula F, Večerek V (2006) Differences in the amino acid composition of muscles from pheasant and broiler chickens. Archives Animal Breeding 49(5): 508-514.

- Aryal K, Poudel S, Chaudhary RP, Chettri N, Chaudhary P (2018) Diversity and use of wild and non-cultivated edible plants in the Western Himalaya. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 14(1).

- Holsberger DR, Donoghue A, Froman D, Ottinger M (1998) Assessment of ejaculate quality and sperm characteristics in turkeys: sperm mobility phenotype is independent of time. Poult Sci 77(11): 1711-1717.

- Penfold LM, Harnal V, Lynch WE, Bird D, Derrickson SR, Wildt DE. Characterization of Northern pintail (Anas acuta) ejaculate and the effect of sperm preservation on fertility. Reproduction. 2001.

- Tuia D, Kellenberger B, Beery S, Costelloe BR, Zuffi S, et al. (2021) Seeing biodiversity: perspectives in machine learning for wildlife conservation. arXiv (Cornell University).

- Applegate RD (2002) Home Ranges of Ring-necked Pheasants in Northwestern KansasThe Prairie Naturalist 34(3/4): 152.

- Farris AL, Klonglan ED & Nomsen RC (1977) The ring-necked pheasant in Iowa. Iowa Conservation Commission.

- Iftikhar A, Yaqoob I (2024) A Brief Review of Current Strategies and Advances in Cryopreservation Techniques. Adv Biotech & Micro 18(1): 555978.

- Leif AP (2005) Spatial ecology and habitat selection of breeding male pheasants. Wildlife Society Bulletin 33(1): 130-141.

- Li H, Zhen-min L, Cun-gen C (2009) Winter foraging habitat selection of brown-eared pheasant (Crossoptilon mantchuricum) and the common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) in Huanglong Mountains, Shaanxi Province. Acta Ecologica Sinica 29(6): 335-340.

- Li H, Zhen-min L, Cun-gen C, Wu S (2009) Seasonal changes in the ranging area of Brown-eared pheasant and its affecting factors in Huanglong Mountains, Shaanxi Province. Acta Ecologica Sinica 29(5): 302-306.

- Rakha BA, Ansari MS, Akhter S, Zafar Z, Naseer A, et al. (2018) Use of dimethylsulfoxide for semen cryopreservation in Indian red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus murghi). Theriogenology 122: 61-67.

- Søraker JS & Dunning J (2023) The costs of extra-pair mating.

- Zhou C, Xu J, Zhang Z (2015) Dramatic decline of the Vulnerable Reeves’s pheasant Syrmaticus reevesii, endemic to central China. Oryx 49(3): 529–534.