- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Multisite Clinical Trial on the ASSYST Individual Treatment Intervention Provided to General Population with Non-Recent Pathogenic Memories

Mainthow Nicolle1, Perez Maria Cristina2, Osorio Amalia2, Givaudan Martha1 and Jarero Ignacio1*

1Department of Research, Mexican Association for Mental Health Support in Crisis, Mexico

2Department of Research, Agape Desarrollo Integral, Mexico

Submission: November 09, 2022; Published: November 18, 2022

*Corresponding author: Ignacio Jarero, Department of Research, Mexican Association for Mental Health Support in Crisis, Mexico City, Mexico

How to cite this article: Mainthow N, Perez M C, Osorio A, Givaudan M, Jarero I. Multisite Clinical Trial on the ASSYST Individual Treatment Intervention Provided to General Population with Non-Recent Pathogenic Memories. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2022; 19(5): 556024. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2022.19.556024.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Abstract

This multisite clinical trial had two objectives: 1) to evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Individual (ASSYST-I) treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety symptoms in the adult general population with pathogenic memories over three months old, and 2) to explore the correlation coefficient between the PCL-5 total 20 items score and the PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score with the anxiety and depression variables. A total of 43 adults (39 females and 4 males) met the inclusion criteria and participated in the study. Participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 78 years old (M =47.34 years). Repeated-measures ANOVA were carried out to observe the effect of the intervention on the variables across three time points (Time 1 pre-treatment, Time 2 post-treatment and Time 3 follow-up). Results showed significant effects of the ASSYST-I on PTSD symptoms, (F (2, 84), 76.17, p= .001, η2 =.645, β-1=1) ; Intrusion symptoms (F (2, 84), 27.53, p= .000, η2 =.360, β-1=1); Anxiety, (F (2, 84), 28.99, p= .000, η2 =.500, β-1=1) and Depression, (F (2, 84), 14.71, p= .000, η2 =.239, β-1=.99). A positive relationship on Times 2 and 3 between the PCL-5 intrusion symptoms and the anxiety and depression symptoms was also found. Findings provide evidence of the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the ASSYST-I in reducing posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in the general adult population with non-recent pathogenic memories.

Keywords: Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization; Posttraumatic stress disorder; Anxiety; Depression; Intrusive memories

Abbreviations: ASSYST: Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization; PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; AIP: Adaptive Information Processing; CAPS-5: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale-5

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a pervasive mental health disorder, affecting about 12 million adults in the US during a given year (approximately 6% of the population of the total US adult general population and 8% of women in the general US population will develop PTSD in their lifetime), with devastating individual and societal effects, such as deterioration of basic functioning, hindrance of personal and professional relationships, and extreme psychological and physiological distress [1]. PTSD leads to maladaptive responses that manifest in different forms, which include, but are not limited to hyperarousal, hypervigilance, flashbacks, nightmares, fear, horror, and impaired affective prosody and inability to adequately interpret emotional cues [2]. Higher PTSD symptoms, specifically intrusion and arousal symptoms, correlate with sleep disturbances and lower emotional quality of life [3,4].

Intrusive memories are re-experienced without context and without the incorporation of new information of the present, meaning the emotions that were felt at the time of the trauma and the somatosensory components are re-experienced as if they were being experienced in the present [5]. Intrusive memories contain the original memory components which occurred right before the traumatic event or during the moment of highest emotional impact (the moment the person realized or understood the danger of the event) event) and therefore were assigned the meaning of danger or threat. These act as a warning signal that danger is eminent, which explains the association between intrusive memories or memory components and extreme psychological and physiological distress [6], impeding the updating of contextual information, indicating on-going danger in a safe, post-trauma environment in these persons’’ everyday lives [7]. Intrusion symptoms can also be accompanied by strongly felt distressing emotions such as anger, humiliation, sadness, guilt, or shame [8].

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

Briefly stated, the Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) theoretical model is a memory-related model of pathogenesis and change that explains the development of personality and pathology [9]. According to this model, memory networks of stored experiences are the basis of both human mental health and human pathology across the clinical spectrum. When the information of an experience is successfully processed, it is adaptively stored in memory networks of experiences that are similar in their components and serves as a guide for future perceptions, behaviors, and responses.

High autonomic nervous system arousal states produced by adverse life experiences produce an AIP disruption that result in memories that are inadequately processed and dysfunctionally stored in the brain. The information stored in these neurophysiological pathogenic memory networks generates the present suffering, difficulties, and symptoms (e.g., PTSD, anxiety, depression) across the clinical spectrum. Based in the growing body of research showing that memories can contribute to pathology in many mental disorders, the AIP theoretical model can be considered a meta-theory and a transdiagnosis model [10,11].

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

The Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization (ASSYST) Individual treatment intervention was born during humanitarian field-work and is an AIP-informed, evidence-based, carefully field-tested, and user-friendly psychophysiological algorithmic approach, whose reference is the EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents and Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-PRECI) [12-20]. This treatment intervention is specifically designed to provide in-person or online support to clients who present Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) intense psychological distress and/or physiological reactivity caused by the disorders’ intrusion symptoms associated with the the memories of the adverse experience(s) [21].

Intrusion symptoms are a core ASD and PTSD dimension and may cause extreme distress, functional impairment, or dissociation from present surroundings. Therefore, focusing on this domain could identify targets specifically related to trauma [22]. “Reducing intrusion symptoms may also have useful downstream effects since they are hypothesized to be a mediator of other PTSD symptom clusters” [23]. The ASSYST Individual treatment intervention gives the clinician the possibility of direct, non-intrusive, physiological engagement with the patient’s pathogenic memories’ original components causing the intrusion symptoms responsible for the Autonomic Nervous System sympathetic branch hyperactivation, the secretion of the three major stress hormones [adrenaline (epinephrine), noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and cortisol] that reinforce the traumatic memory persistence, and the decrease of the Prefrontal Cortex functions (e.g., processing of information) [24-26].

The objective of this treatment intervention is focused on the patient’s Autonomic Nervous System sympathetic branch hyperactivation regulation through the reduction or removal of the activation produced by the sensory, emotional, or physiological components of the pathogenic memories of the adverse experience(s) to achieve optimal levels of Autonomic Nervous System activation, stop the three major stress hormones secretion, and reestablish the Prefrontal Cortex functions (e.g., processing of information); thus, facilitating the AIP-system and the subsequent adaptive processing of information [27].

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Objectives

The objectives of this multisite clinical trial were 1) to evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Individual (ASSYST-I) treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety symptoms in the adult general population with pathogenic memories over three months old, and 2) to explore the correlation coefficient between the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) total 20 item score and the PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score with the anxiety and depression variables.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Method

Study Design

To measure the effectiveness of the ASSYST-I on the dependent variables PTSD, Anxiety, and Depression, this study used a singlearm pre-post-follow-up treatment design. PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms were measured in three-time points for all participants in the study: Time 1. Pre-treatment assessment; Time 2. Post-treatment assessment; and Time 3. Follow-up assessment.

Ethics and Research Quality

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board (also known in the United States of America as an Institutional Review Board) in compliance with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommendations, the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice of the European Medicines Agency (version 1 December 2016), and the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013.

Participants

This study was conducted at five different outpatient sites during 2022 in Mexico with the Mexican (Latino) adult general population with pathogenic memories produced by adverse life experiences over three months old. Fifty-four potential participants were recruited. Inclusion criteria were: (a) being an adult, (b) having a pathogenic memory over three months old causing current distress, (c) voluntarily participating in the study, (d) not receiving specialized trauma therapy, (e) not receiving drug therapy for PTSD symptoms, (f) having a PCL- 5 total score of 22 points or more. Exclusion criteria were: (a) ongoing self-harm/suicidal or homicidal ideation, (b) diagnosis of schizophrenia, psychotic, or bipolar disorder, (c) diagnosis of a dissocitive disorder (d) organic mental disorder, (e) a current, active chemical dependency problem, (f) significant cognitive impairment (e.g., severe intellectual disability, dementia), (g) presence of uncontrolled symptoms due to a medical illness.

Eleven potential participants were excluded. One due to ongoing self-harm/suicidal or homicidal ideation. One due to a current active chemical dependency problem. One due to a diagnosis of schizophrenia. One due to receiving specialized trauma therapy, and seven due to having PCL-5 scores under 22 points. therapy, and seven for having PCL-5 scores under 22 points. A total of 43 adults (39 females and 4 males) met the inclusion criteria and participated in the study. Participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 78 years old (M = 47.34 years). Participation was voluntary with the participants’ signed informed consent in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Instruments for Psychometric Evaluation

a) To measure PTSD symptom severity and treatment response we used the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) provided by the National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD) with the time interval for symptoms to be the past week. The instrument was translated and back translated to Spanish. It contains 20 items, including three new PTSD symptoms (compared with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-IV) [28,29]: blame, negative emotions, and reckless or self-destructive behavior. Respondents indicate how much they have been bothered by each PTSD symptom over the past week (rather than the past month), using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0= not at all, 1= a little bit, 2= moderately, 3= quite a bit, and 4= extremely. A totalsymptoms score of zero to 80 can be obtained by summing the items. The sum of the scores yields a continuous measure of PTSD symptom severity for symptom clusters and the whole disorder. Psychometrics for the PCL-5, validated against the Clinician- Administered PTSD Scale-5 (CAPS-5) diagnosis, suggest that a score of 31-33 is optimal to determine probable PTSD diagnosis, and a score of 33 is recommended for use at present [30,31].

b) To measure anxiety and depression symptoms severity and treatment response we used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) which has been used to evaluate these psychiatric comorbidities in various clinical settings at all levels of healthcare services and with the general population. The instrument was translated and back translated to Spanish. It is a 14-item self-report scale to measure the Anxiety (7 items) and Depression (7 items) of patients with both somatic and mental problems using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The response descriptors of all items are Yes, definitely (score 3); Yes, sometimes (score 2); No, not much (score 1); No, not at all (score 0). A higher score represents higher levels of Anxiety and Depression: a domain score of 11 or greater indicates Anxiety or Depression; 8–10 indicates borderline case; 7 or lower indicates no signs of Anxiety or Depression [32,33].

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Procedure

Enrollment, Assessments Times, Blind Data Collection, and Confidentiality of Data

The invitation to participate in the study was made through social networks (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp) and word-of-mouth with a phone number for the intake interview. All participants completed the self-administered instruments online on an individual basis in the three different assessment times. During Time 1, research assistants (mental health professionals), blind to the participant’s allocation to clinicians, conducted the intake interview by phone, assessed potential participants for eligibility based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, collected their data (e.g., name, age, gender, profession, email, telephone), obtained signed informed consent, enrolled participants in the study, and sent the participant’s data to the data safe keeper independent assessor.

After this procedure, another research assistant (not involved in the research study) sent each of the enrolled participants a link to answer the Time 1 (pre-treatment) assessment instruments online, and randomly assigned them to one of the eleven clinicians formally trained in the ASSYST-I that participated in this study. The data safe keeper independent assessor received the participant’s assessments instruments that were already answered online during Times 1, 2, and 3. At no point did the clinicians have access to the assessment scores. Time 2 post-treatment assessment was conducted online 15 days after the ASSYST-I treatment completion, and Time 3 follow-up assessment was conducted online 30 days after the ASSYST-I treatment intervention completion, both following the same above-mentioned procedure. All data was collected, stored, and handled in full compliance with the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board requirements to ensure confidentiality. Each study participant gave their consent for access to their data, which was strictly required for study quality control. All procedures for handling, storing, destroying and processing data were in compliance with the Data Protection Act 2018. All persons involved in this research project were subject to professional confidentiality.

Withdrawal from the Study

All research participants had the right to withdraw from the study without justification at any time and with assurances of no prejudicial result. If participants decided to withdraw from the study, they were no longer followed up in the research protocol. There were no withdrawals during this study.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Treatment

Clinicians and Treatment Fidelity

The ASSYST-I was provided in-person to individual participants by eleven licensed clinicians formally trained in this treatment intervention. Clinicians received on-going supervision and clinical feedback from the research project Clinical Director through the submission of audio-recorded sessions and detailed session summary forms that were designed specifically for the ASSYST-I treatment intervention, and structured to elicit, monitor, and facilitate treatment intervention adherence.

Treatment Description and Treatment Safety

The intake interview was made by phone for each potential participant to receive the ASSYST-I treatment intervention. Participants’ treated memories were an average of 282.61 weeks (5.43 years) old and received an average of 2.9 in-person sessions, with an average of 52 minutes per session once a week. treatment The ASSYST-I intervention focused only on the pathogenic memory selected during T1 pre-treatment assessment to answer all the assessment intruments. To ensure the continuity and congruency of the intervention and measurement of its efficiency and efficacy, during the first session the clinician asked the participant what pathogenic memory they had maintained in mind when answering the PCL-5 and the HADS in the pretreatment assessment. The participant was asked to run a mental movie of that specific memory, and then to choose the worst part. The treatment intervention was considered complete when the participant’s subjective levels of disturbance associated with the pathogenic memory decreased to to zero or an ecological (realistic) one. It took an average of 2.9 sessions to achieve the treatment completion.

At the end of the treatment intervention each participant was reminded by the clinician to answer the PCL-5 and HADS for the T2 and T3 assessments regarding the same memory that was the focus of the sessions.

Treatment safety was defined as the absence of adverse effects, events, or symptoms worsening. Therefore, participants were instructed by their clinicians to immediately report to them any adverse effects (e.g., dissociative symptoms [derealization/ depersonalization], fear, panic, freeze, shut down, collapse, fainting); events (e.g., suicide ideation, suicide attempts, selfharm, homicidal ideation); or symptoms worsening, during the entire study time frame. The research project Clinical Director monitored attrition, adverse effects, events, or worsening of symptoms during the study.

Examples of the Pathogenic Memories Treated with the ASSYST-I

Examples of the pathogenic memories during the ASSYST-I sessions were: a) childhood sexual abuse by a parental figure and the image of the parental figure’s face; b) a partner dying in prison and not being allowed to see the body for months and the smell of the corpse when finally given access to see the partner; c) being left by a partner while pregnant and the feeling of abandonment; d) a mother’s daughter being sentenced to jail and the fear of never seeing her again; d) a parent dying and having to carry the body to the ambulance and the feeling of the weight of carrying the parent in their arms; e) a sibling in an intimate partner violence relationship and the image of the sibling in the hospital with severe, near death injuries; f) medical negligence leading to the removal of a fetus while unknowingly seven months pregnant instead of a tumor and the image of the removed fetus; g) sexual assault and the feeling of being touched, specifically in the pelvic area; h) the suicide of a partner and the feeling of guilt; i) the diagnosis of a terminal illness and subsequent death of a child and the feeling of powerlessness.

Clinicians’ Experience with the ASSYST Treatment Intervention

The eleven clinicians who participated in the research study answered the following questions about their experience as clinicians using the ASSYST-I: 1) How did using the ASSYST-I in this research project impact your confidence as a clinician? 2) How did it make you feel as a clinician to use the ASSYST-I with your patients? In response to the first question, regarding confidence, all clinicians reported an increase in confidence as a result of implementing the ASSYST-I. All clinicians reported that: i) the highly manualized structure of the scripted treatment intervention increased their confidence as clinicians because the script was easy to follow, easy to implement, and clinicians were able to simply rely on the script, follow the instructions, and this elicited the desired results in their patients. ii) witnessing their patients’ high levels of distress and suffering transform into a state of psychological and physical calm in their presence in very little time, increased their confidence as clinicians. iii) their patients’ self-report of decreased or eliminated intrusion symptoms increased their confidence as clinicians in the knowledge they have an effective tool.

In response to the second question, regarding the emotional experience as a clinician using the ASSYST-I, clinicians reported varying types of pleasant emotions. For example, feeling strengthened, rejuvenated, hopeful, and excited. Clinicians also reported a decreased sense of hopelessness, powerlessness, and burnout. Clinicians stated their emotional responses in using the ASSYST-I were due to witnessing positive results in patients in working with pathogenic memories and intrusion symptoms which seemed “impossible” to provide relief for.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Statistical Analyses

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measurements (Time 1 pre-treatment, Time 2 post-treatment, and Time 3 followup) was applied to analyze the effects of the treatment on PTSD, Anxiety, and Depression symptoms. Within means comparisons is reported including eta squared (η2) to report the effect size. Bonferroni adjustment was used as post hoc analysis. In order to explore the correlation coefficient between the PCL-5 total score and the PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score with the anxiety and depression variables, a series of correlation analyses were done by application time.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Results

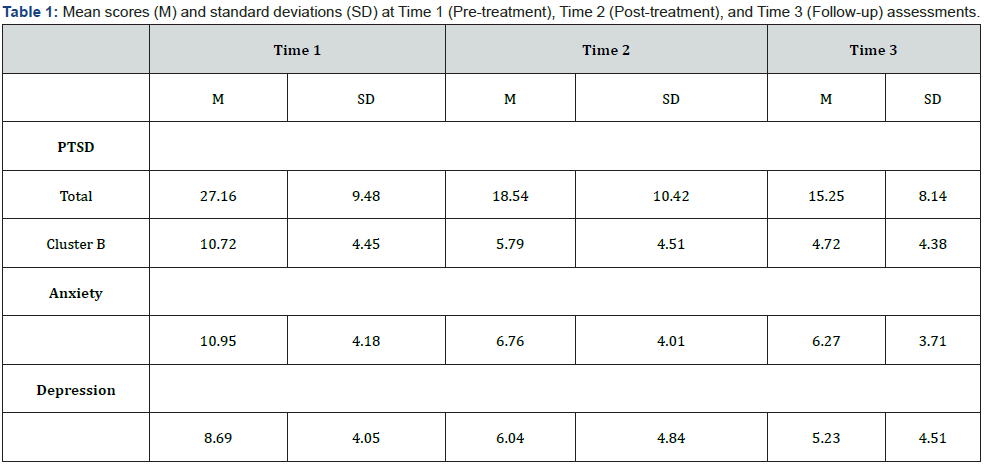

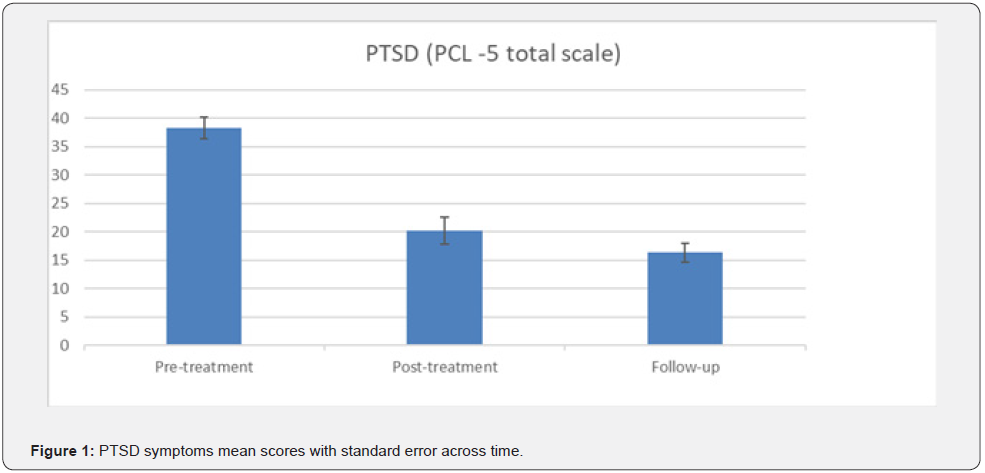

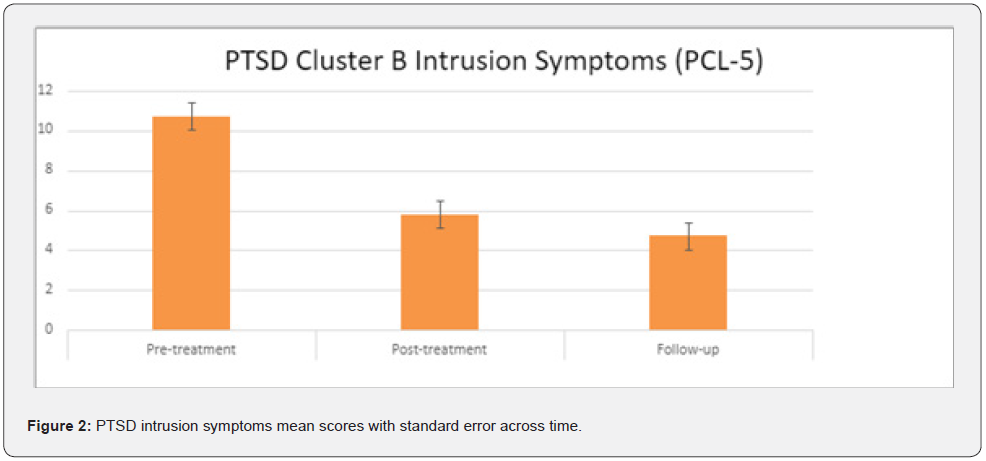

PTSD symptoms

A repeated-measures ANOVA determined that mean scores on PTSD symptoms, measured using PCL-5 total score, differed significantly across three time points with a large effect size (F (2, 84), 76.17, p= .001, η2 =.645, β-1=1). A post hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed statistically significantly decreased (p= .001) from Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 2 posttreatment (M= 38.30, SD= 12.32 vs M=20.16, SD=15.52) and from Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 3 follow-up (M= 38.30, SD= 12.32 vs M=16.37, SD=10.81). (Table 1 & Figure 1). Another repeatedmeasures ANOVA was done using only PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms on the of PCL-5. Results showed significantly decreased across the three time points, (F (2, 84), 27.53, p= .000, η2 =.360, β-1=1). A post hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed statistically significantly decreased (p= .001) from pre- Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 2 post-treatment (M= 10.72, SD= 4.45 vs M=5.79, SD= 4.51), and from Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 3 follow-up (M= 10.72, SD= 4.45 vs M= 4.72, SD= 4.38) (Table 1 & Figure 2).

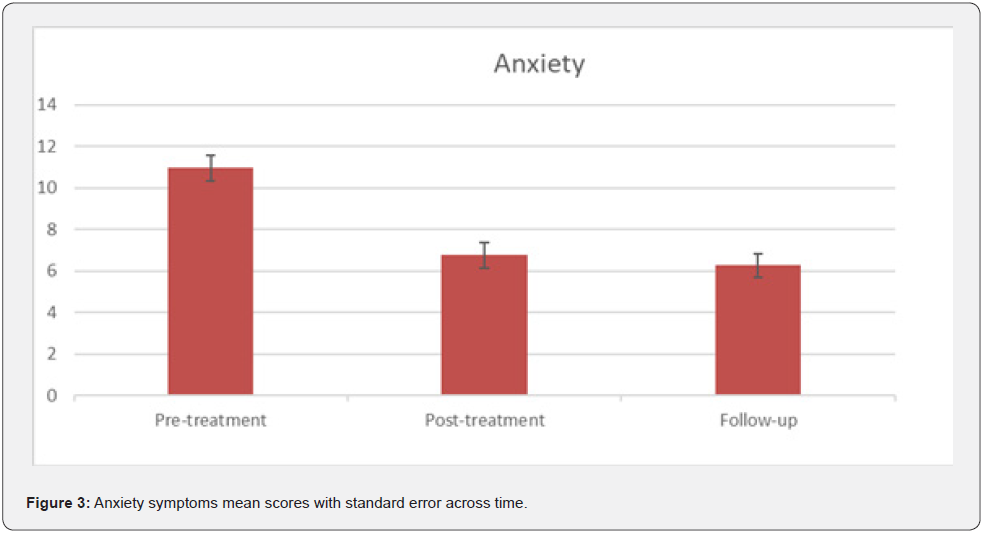

Anxiety symptoms

A repeated-measures ANOVA determined that mean scores on anxiety symtoms, differed significantly across three time points (F (2, 84), 28.99, p= .000, η2 =.500, β-1=1). A post hoc analysis using Bonferroni adjustment showed statistically significantly decreased (p= .001) from Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 2 posttreatment (M= 10.95, SD= 4.18 vs M= 6.76, SD= 4.01), and from Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 3 follow-up (M= 10.95, SD= 4.18 vs M= 6.27, SD= 3.71) (Table 1 & Figure 3).

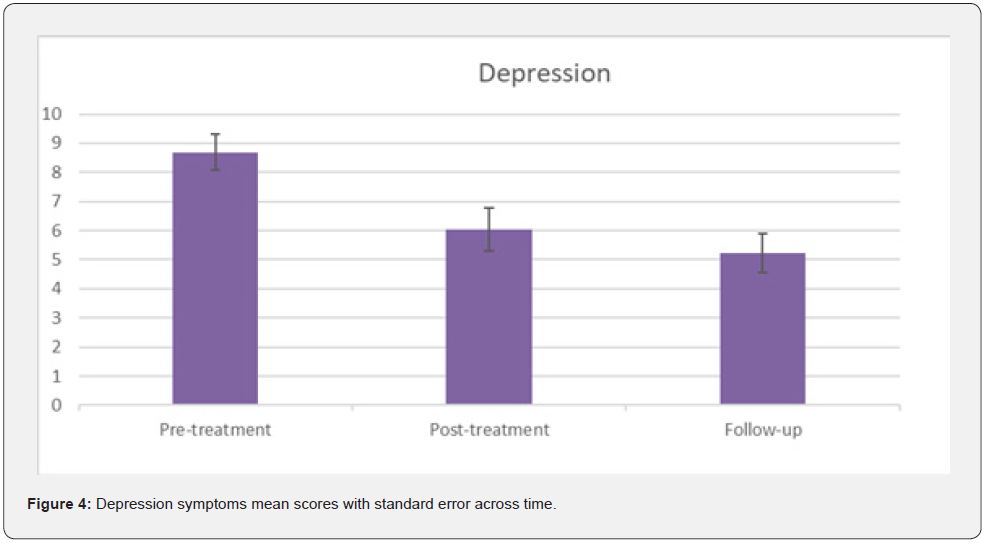

Depression symptoms

A repeated-measures ANOVA determined that mean scores on depression symtoms, differed significantly across three time points (F (2, 84), 14.71, p= .000, η2 =.239, β-1=.99). Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni adjustment showed statistically significantly decreased (p= .002) from Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 2 post-treatment (M= 8.69, SD= 4.05 vs M= 6.04, SD= 4.84), and a significant decreased (p=.000) from Time 1 pre-treatment to Time 3 follow-up (M= 8.69, SD= 4.05 vs M= 5.23, SD= 4.51) (Table 1 & Figure 4).

Correlation analyses

Time 1: A Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relationship between PCL-5 total score and anxiety and PCL-5 (total score) and depression at Time 1. There was a positive correlation between the PCL-5 (total score) and anxiety, r (41) = .57, p = .000; and PCL-5 total score and depression, r (41) = .44, p=.003. A Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relationship between the PCL- 5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score with anxiety and depression. No significant correlation was found at Time 1.

Time 2: A Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relationship between PCL-5 total score and anxiety and PCL-5 (total score) and depression at Time 2. There was a positive correlation between the PCL-5 (total score) and anxiety, r (41) = .787, p = .000; and PCL-5 total score and depression, r (41) = .789, p=.000. Pearson correlation coefficient showed a positive relationship between the PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score and anxiety, r (41) = .735, p = .000; and also, depression, r (41) = .680, p=.000.

Time 3: A Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relationship between PCL-5 total score and anxiety and PCL-5 total score and depression at time 3. There was a positive correlation between the PCL-5 total score and anxiety, r (41) = .48, p = .001; and PCL-5 total score and depression, r (41) = .42, p=.004. Pearson correlation coefficient showed a positive relationship between the PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score and anxiety, r (41) = .37, p = .01; and also depression, r (41) = .50, p=.001.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Discussion

This multisite clinical trial had two objectives: 1) to evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Individual (ASSYST-I) treatment intervention in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety symptoms in the adult general population with pathogenic memories over three months old, and 2) to explore the correlation coefficient between the PCL-5 total 20 items score and the PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score with the anxiety and depression variables. A total of 43 adults (39 females and 4 males) met the inclusion criteria and participated in the study. Participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 78 years old (M =47.34 years). Results showed that this treatment intervention, designed to provide support to patients with ASD or PTSD intense psychological distress and/or physiological reactivity, was effective to significantly decrease PTSD symptoms in general and intrusion symptoms in particular, as well as anxiety and depression symptoms.

It is interesting to note that both the PCL-5 total score and the PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score showed a significant decrease across time. However, the effect size was lower using the 5 intrusion symptoms items in comparison with the PCL-5 total score. Correlation analyses between PCL-5 total score with anxiety and depression symptoms, and PCL-5 PTSD Cluster B five intrusion symptoms score with anxiety and depression, showed that at Time 1 (pre-treatment) there was no correlation between intrusion symptoms with anxiety and depression while there was a positive correlation between the variables using the total PCL-5 score. Nevertheless, after treatment there was a significant decrease for both PTSD symptoms and intrusion symptoms and then we observe a positive correlation with anxiety and depression at time 2 (post-treatment) and time 3 (follow-up), with similar correlation coefficients for the PCL-5 total score and the PCL-5 five intrusion symptoms items with the anxiety and depression. Further studies are needed for a better understanding of this finding.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

PTSD is a pervasive mental health disorder with frequent anxiety and depression comorbidity which has devastating effects on individuals and society. Intrusion symptoms are a core PTSD dimension and can guide clinicians in identifying the moments with the largest emotional impact that will need immediate treatment. Therefore, there is a need for evidence-based, time-limited, cost-effective, and safe interventions to enhance treatment of posttraumatic psychopathology.

The study results showed that the ASSYST-I treatment intervention can effectively, efficiently, and safely be provided inperson to the adult general population with non- early pathogenic memories to reduce PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms. No adverse effects or events were reported by the participants during the treatment procedure administration or at one-month follow-up. None of the participants showed clinically significant worsening/exacerbation of symptoms on the PCL-5 or HADS after treatment.

Clinicians’ reports based on their experiences also suggest that the ASSYST-I is a clinician friendly treatment intervention that can be successfully applied by novice and seasoned clinicians alike, yielding similar treatment results, facilitating clinician confidence.

Limitations of this study are the lack of a control group, the small sample and the 30-days follow-up. Therefore, we recommend a randomized controlled trial with the adult general population on older pathogenic memories (e.g., adverse childhood experiences) or on PTSD Criteria-A experiences, with larger samples and with follow-up at three or six months to evaluate the long-term treatment effects.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

Acknowledgment

We want to express our gratitude to all the clinicians and research assistants that participated in this study: Lara Maria Gómez Trejo, Edda Gabriela Pelayo Maurer, Rosa Zapien, Amalia Osorio Vigil, Luz Elena Torres Peregrina, Yazmin Maldonado Aviles, María Jenny Hidalgo Ramé, Mónica Sánchez, Reyna Elizalde, Josefina Pérez Gómez, María Cristina Pérez Grados, Fernanda Navarro Huerta, and Javier Alonzo Alonzo.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Adaptive Information Processing Theoretical Model and Pathogenic Memories

- Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Treatment Intervention

- Objectives

- Method

- Procedure

- Treatment

- Statistical Analyses

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

- Acknowledgment

- References

References

- (2018) How Common is PTSD in Adults? US Department of Veteran’s Affairs: National Center for PTSD.

- Romero DE, Anderson A, Gregory JC, Potts CA, Jackson A, et al. (2020) Using neurofeedback to lower PTSD symptoms. NeuroRegulation 7(3): 99-106.

- Slavish DC, Briggs M, Fentem A, Messman BA, Contractor AA (2022) Bidirectional associations between daily PTSD symptoms and sleep disturbances: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 63: 101623.

- Burgos A, Bargiel-Matusiewicz KM (2018) Quality of life and PTSD symptoms, and temperament and coping with stress. Front Psychol 9: 2072.

- Speckens A, Ehlers A, Hackmann A, Clark D (2006) Changes in intrusive memories associated with imaginal reliving in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord 20(3): 328-341.

- Ehlers A, Hackmann A, Steil R, Clohessy S, Wenninger K, et al. (2002) The nature of intrusive memories after trauma: the warning signal hypothesis. Behav Res Ther 40(9): 995-1002.

- Sopp MR, Haim-Nachum S, Wirth BE, Bonanno GA, Levy-Gigi E (2022) Leaving the door open: trauma, updating, and the development of PTSD symptoms. Behav Res Ther 154: 104098.

- Kleim B, Graham B, Bryant RA, Anke E (2013) Capturing intrusive re-experiencing in trauma survivors’ daily lives using ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol 122(4): 998-1009.

- Hase M, Balmaceda UM, Ostacoli L, Liebermann P, Hofmann A (2017) The AIP Model of EMDR Therapy and Pathogenic Memories. Front Psychol 8: 1578.

- Shapiro F (2018) Eye movements desensitization and reprocessing. Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (Third edition). Guilford Press.

- Centonze D, Siracusane A, Calabresi P, Bernardi G (2005) Removing pathogenic memories. Mol Neurobiol 32(2): 123-132.

- Jarero I, Artigas L, Luber M (2011) The EMDR protocol for recent critical incidents: Application in a disaster mental health continuum of care context. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 5(3): 82-94.

- Jarero I, Uribe S (2011) The EMDR protocol for recent critical incidents: Brief report of an application in a human massacre situation. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 5(4): 156-165.

- Jarero I, Uribe S (2012) The EMDR protocol for recent critical incidents: Follow-up Report of an application in a human massacre situation. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 6(2): 50-61.

- Jarero I, Amaya C, Givaudan M, Miranda A (2013) EMDR Individual Protocol for Paraprofessionals Use: A Randomized Controlled Trial Whit First Responders. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 7(2): 55-64.

- Jarero I, Uribe S, Artigas L, Givaudan M (2015) EMDR protocol for recent critical incidents: A randomized controlled trial in a technological disaster context. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 9(4): 166-173.

- Jarero I, Schnaider S, Givaudan M (2019) EMDR Protocol for Recent Critical Incidents and Ongoing Traumatic Stress with First Responders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 13(2): 100-110.

- Encinas M, Osorio A, Jarero I, Givaudan M (2019) Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial on the Provision of the EMDR-PRECI to Family Caregivers of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychol Behav Sci Int J 11(1): 1-8.

- Estrada BD, Angulo BJ, Navarro ME, Jarero I, Sanchez-Armass O (2019) PTSD, Immunoglobulins, and Cortisol Changes after the Provision of the EMDR- PRECI to Females Patients with Cancer-Related PTSD Diagnosis. American Journal of Applied Psychology 8(3): 64-71.

- Jimenez G, Becker Y, Varela C, Garcia P, Nuno MA, et al. (2020) Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial on the Provision of the EMDR-PRECI to Female Minors Victims of Sexual and/or Physical Violence and Related PTSD Diagnosis. American Journal of Applied Psychology 9(2): 42-51.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

- Kleim B, Graham B, Bryant RA, Anke E (2013) Capturing intrusive re-experiencing in trauma survivors’ daily lives using ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol 122(4): 998-1009.

- Astill WL, Horstmann L, Holmes EA, Jonathan IB (2021) Consolidation/reconsolidation therapies for the prevention and treatment of PTSD and re-experiencing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 11(1): 453.

- Becker Y, Estevez ME, Perez, MC, Osorio A, Jarero I, et al. (2021) Longitudinal Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial on the Provision of the Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Remote for Groups to General Population in Lockdown During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol Behav Sci Int J 16(2): 1-11.

- Smyth-Dent K, Becker Y, Burns E, Givaudan M (2021) The Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Remote Individual (ASSYST-RI) for TeleMental Health Counseling After Adverse Experiences. Psychol Behav Sci Int J 16(2): 1-7.

- Magalhaes¸SS, Silva CN, Cardoso MG, Jarero I, Pereira Toralles MB (in press). Acute Stress Syndrome Stabilization Remote for Groups Provided to Mental Health Professionals During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Bahía Federal University. Health Sciences Institute. Brazil.

- Jarero I (2021) ASSYT Traeatment Procedures Explanation. Research Gate.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, et al. (2013) The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, et al. (2016) Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders- Firth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess 28(11): 1379-1391.

- Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, et al. (2013) Clinician-administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5. National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Boston.

- Franklin CL, Raines AM, Cucurullo LA, Chambliss JL, Maieritsch KP, et al. (2018) 27 ways to meet PTSD: Using the PTSD-checklist for DSM-5 to examine PTSD core criteria. Psychiatry Res 261: 504-507.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith, RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6): 361-370.

- Ying Lin C, Pakpour AH (2017) Using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) on patients with epilepsy: Confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch models. Seizure (45): 42-46.