A Tale of Two Cities in Israel: Motivated Reasoning Explains the Impact of Political Literacy on Political Attitudes

Leah Borovoi1, Krishane Patel2 and Ivo Vlaev2*

1Open University Israel, Israel

2University of Warwick, England

Submission: December01, 2020; Published: March 16, 2021

*Corresponding author: Professor Ivo Vlaev, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, Scarman Road, Coventry, CV4 7AL, United Kingdom

How to cite this article: Borovoi L, Patel K, Vlaev I. A Tale of Two Cities in Israel: Motivated Reasoning Explains the Impact of Political Literacy on Political Attitudes. Psychol Behav Sci Int J .2021; 16(3): 555939. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555939.

Abstract

This study explores the relationship between political literacy and political attitudes. 185 participants completed a questionnaire that measured their political literacy (answering questions such as: “who is the current Minister of Education?”) and a questionnaire that measured their political preferences to the left or the right. The results indicated greater political literacy was associated with greater political polarization. As political literacy test scores increased, participants tended to express more extreme attitudes and higher political engagement either to the right or to the left. We argue that the asymmetry within the information search and the confirmation bias underlie this effect. The information people read on political issues is not random but chosen by a-priori political views. Respondents predisposed by their background, family, religion, origin and residence to the left/right political wing become more left/right as they attenuate to more liberal/conservative news. Participants tended to dismiss political information that critics their views but take seriously political articles that support their prior beliefs. The more political information people read, the higher their political literacy, and the more likely they are to become extreme in their prior beliefs. Implications to political decision-making are discussed.

Keywords:Motivated reasoning; Political attitudes; Attitude polarization; Psychics; Psychological processes; Behaviour,

Introduction

Winston Churchill famously said: “The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter” ([1] pp.170). Recent surveys demonstrate that people barely possess political knowledge, 70% of young American adults could not locate Israel or Iran, 90% could not locate Afghanistan, 54% did not know Sudan is in Africa and 75% did not know Indonesia is the largest Muslim country in the world [2]. Political illiteracy is a considerable problem if the public is unable to comprehend the severity of issues such as climate change, gun violence, national security, population growth and so on. The controversy over these issues is predominant in America, with large disagreement between left-wing and right-wing views on major political issues [3]. For instance, consider climate change, liberals generally attribute the cause of global warming to human activity; on the other hand, conservatives tend to affirm that global warming is due to natural patterns [4]. Liberals display a tendency to accept significant scientific evidence that suggests there is a 95% probability that humans are the cause of global warming, whilst conservatives tend to accept significant amount of scientific evidence criticizing environmental risks, such as ozone depletion, DDT, and passive smoking [5-12]. Chris Mooney, author of The Republican War on Science, has argued that the appearance of overlapping groups of sceptical scientists, commentators and think tanks in seemingly unrelated controversies results from an organized attempt to replace scientific analysis with political ideology [13]. Liberals often accuse conservatives in being not scientific enough, whilst conservatives accuse liberals in being not critical enough.

Political polarization is become an increasing problem internationally. Consider the recent improving support for the UK Independence Party within the UK, or the Golden Dawn party within Greece, which was able to win 6.9% of the popular vote in the 2011 Greek general election [14]. There has been a dramatic rise in extreme political views in recent years, in which immigration has become a major political issue [15]. Political attitudes have become increasingly extreme, with political polarization infringing on democratic and societal issues, such as healthcare [16]. In fact, political attitudes within the US have indeed become increasingly polarized over time [17]. The distribution of political attitudes has seen a transformation from a typical bell-shaped distribution towards a platykurtic distribution in the last twenty years. The proportion of individuals who see themselves as consistently liberal or conservative (as opposed to mostly liberal or conservative) has increased from 1994 to 2014 (a 9% increase for liberal attitudes and a 2% increase for conservative attitudes). Another example of the extent to which political attitudes are polarized is evident in the change of overlap between Republicans and Democrats. In 2014 92% of Republicans had views to the right of the median Democrat, compared to 64% in 1994, an increase of 28%. With the same effect in Democrats, in 2014, 94% of Democrats are to the right of the median Republican compared in 70% in 1994, an upwards shift of 24%. What could be causing such dramatic polarisation of political attitudes?

In this article we are focusing on understanding the existence of polarization, regardless of the place and time.

Motivated Reasoning

People’s perceptions and judgements are often influenced by their beliefs and values, as exemplified by Hastorf and Cantril [18] who demonstrated that students at an American football match reported a biased perception of players’ behaviour in support of the college they attended. There is evidence of similar behaviour within politics, for example Young, Ratner and Fazio [19] demonstrated that voters tend to construct their own worldview of politics that fits their own political beliefs. Such behaviour is characteristic of motivated reasoning, which is postulated to consist of an interaction between affective and cognitive processing [20]. People will criticize and underweight information that is inconsistent with prior beliefs and overweight evidence that is congruent with such values, analogous to the optimism bias [21]. Such reasoning biases people to weight available information differently depending on whether or not it is congruent to their own beliefs, information that is congruous becomes over-weighted, and counter-evidence against a belief is underweighted and even dismissed [22]. Lebo and Cassino [23] illustrated how motivated reasoning can influence the attitudes towards political figures, discounting and even ignoring counterevidence. Motivated reasoning has even been demonstrated to bias voter attitudes. In a study by Slothuus and De Vreese [24], participants were either shown a pro-welfare or anti-welfare sponsored by one of two political parties from Denmark. The results showed that participants displayed more support when the party and its welfare position were congruous. These effects were even more pronounced amongst participants who were more politically literate.

These beliefs can be held by a single individual or be shared by multiple members of a social group [25]. Thus, individuals or members of the same group will be motivated to resist or accept empirical evidence such as whether gun control influence crime rates [26], if such conclusions are in parallel or run perpendicular to the dominant beliefs shared by the group [27]. Research has illustrated how motivated reasoning can influence public opinion in mass in formulating perceptions of political candidates. Evidence from examining confirmation bias (also known as myside bias) provides some support for motivated reasoning; people will behave in a manner to conform to their expectations and beliefs [28-30], suggesting that the confirmation bias may be an underlying mechanism of motivated reasoning. Such behaviour can have adverse effects; for instance, investors will show a confirmation bias in favour of their investments and will underweight contradictory evidence [31]. Psychics or wishful thinking demonstrates how evidence and information becomes distorted to a meaningful attribute that is central to the individual [32], when asked about a psychics ability people express a selective memory and will demonstrate a biased recall in favour of hits over misses [33]. Researchers have even determined that voter behaviour often display signs of a motivated reasoning, voters will select and identify congruent information and tend to miss or skim over incongruent information for a preferred political candidate [34].

Kahan and colleagues have examined the role of Motivated Reasoning or a collective version, they term Cultural Cognition, within the public domain on political debates [3,35-38]. Cultural Cognition denotes a conformity to a given perception or attitude based upon the shared characteristics of the in-group to which one is a member of. For instance, Kahan et al. [38] examined the role of cultural cognition on the perceived associated risk of climate change. The researchers compared two theories, the first which they term as the ‘science comprehension thesis’ (SCT), and the ‘cultural cognition thesis’ (CCT). SCT suggests that the lack of perceived risk with climate change is brought about by a significant lack of knowledge about science and numeracy. CCT on the other hand suggests that people form perceptions of societal risks that are congruent with the values of their in-group. The paper compares risk attitudes on a 1-10 scale, where 1 indicates ‘no risk’ and 10 denotes ‘extreme risk’. SCT predicts higher scientific literacy should be associated with a heightened perception of climate change risk. The results, however, contradicted this theory, risk perception decreased as literacy increased. The results aligned more closely with predictions of CCT, which stipulate polarization of risk perceptions based upon the social norms of their in-group. Risk attitudes were divergent for Hierarchical Individuals (tendency to be skeptical of environmental risks) and Egalitarian Individuals (morally suspicious of commerce and industry). CCT was able to provide a better fit of the data, where perceptions of risk were polarized as scientific literacy increased. Such findings suggest literacy does play a role in polarization and could apply to political attitudes (an alternative explanation also could be that low knowledge is correlated with political apathy).

Predictions

Motivated Reasoning provides testable predictions. The theory assumes that the initial political orientation of a member of the public is a random process that takes place over their adolescence and childhood, there are numerous factors involved such as the political information that their parents raise you with [39], the political attitudes or their friends, even a person’s neurobiology [40]. These factors generate different political attitudes based on a person’s contextual upbringing, i.e. one’s social group. Motivated reasoning suggests that people would be likely to initially formulate attitudes and preferences a-priori, but such attitudes would in turn influence what political information is sought after, how such information is processed. Consider a teenager learning politics at school, they may adopt a slightly conservative political stance, according to the above accounts, this would bias attention towards conservative political information as well as how political information is weighted. Cognitive factors such as confirmation bias cause the teenager to search and value information that conform to his or her beliefs. It becomes integrated, and conflicting evidence is underweighted and dismissed [41]. This adolescent would therefore be motivated to assimilate evidence in favour of the conservative view they have adopted and dismiss evidence in favour of a liberal stance. As such, this would systematically reinforce the conservative view of the child, shifting him further to the right. Such models would predict that political attitudes would be formulated under uncertainty, and for those with little political literacy and knowledge, their stances would be mostly central; however, as political literacy increases, there should be a divide that demonstrates a polarization of attitudes, with slightly left views become more liberal and slightly right views becoming increasingly conservative. ( Foot note 1)

The political science literature has already offered test of this hypothesis. Taber and Lodge [26] revealed the role of motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs, while Taber, Cann and Kucsova [42] show the motivated processing of political arguments. Crucially, both studies experimentally found what they called the sophistication effect: the politically knowledgeable are more susceptible to motivated bias. This is often because they possess greater knowledge with which to counter-argue incongruent facts and arguments. They also report a confirmation bias – the seeking out of confirmatory evidence-when the participants are free to self-select the source of the arguments they read. Those studies also find strong evidence of attitude polarization for the politically sophisticated (knowledgeable) participants. Thus, those two studies offer a powerful evidence for the prevalence of motivated reasoning. Because such results have far-reaching implications for scholarship and decision theory (given that the very citizens displaying political knowledge and sophistication, appear to be the most susceptible to motivated reasoning), our study aimed to replicate those findings in a novel, politically-charged context (Israel), using a field study approach. Two contrasting cities in Israel were chosen for this project, Tel Aviv and Ariel. These two cities have opposing political affiliations; Tel Aviv is a very liberal city and is considered the focal point of liberalism in Israel [43]. Ariel on the other hand is a much more right-wing jurisdiction in Israel [44]. These contrasting sites, where different political attitudes are formed, should allow us to test the predictions of Motivated Reasoning by contrasting the political attitudes of those with high and low political literacy.

The Study

This study was conducted to conclude whether political attitudes could be predicted by Motivational Reasoning. The study focused on political literacy and attitudes from students at the Tel Aviv University and Ariel University, due to respectively, the institutions’ liberal and conservative views.

Sample

Students were recruited by opportunistic means from Ariel University and Tel Aviv University. Students were approached on campus and asked to participate in a five minute experiment. The sample consisted of 90 participants from Ariel University (50 Female; Mean age = 24.4 years; SD = 2.04 years) and 95 participants from Tel Aviv University (52 Female; Mean age = 23.8 years; SD = 2.01 years).

Apparatus and Stimuli

Participants were given a political questionnaire (see Appendix A), which took around five minutes to complete and consisted of twenty-nine items. The questionnaire examined: political literacy (16 items), political involvement (7 items), news coverage (4 items) political attitudes (2 items) and finally general demographic information (3 items). The items were created specifically for the purpose of this research by the researchers. Alpha was .75.

Political literacy was assessed using open and closed-ended questions about the Israeli government, as well as identification tasks of key governmental figures. This component consisted of twelve closed questions and four open-ended. The four openended questions required two, three or even four-part answers. Closed questions were treated on a binary fashion as correct or incorrect, but open questions yielded part-marks as some participants failed to fully answer the question. The political attitudes component consisted of two items: one examining the extent to which participants perceive themselves as right or left on a five-point scale (where ‘1’ denoted an extreme conservative view and ‘5’ constituted an extreme liberal view); a second item investigating which political party participants vote for. The questionnaire was conducted by means of pen and paper on a clipboard carried by the examiner.

Procedure

Political literacy

Political literacy scores were compared between Tel Aviv and Ariel to determine whether a given political attitude is associated with politically literate. Tel Aviv showed a slightly larger range and variance of literacy scores (M = 9.47, SD = 2.97, Range = 14.00), whereas Ariel University showed a smaller range in the distribution of political literacy scores (M = 8.81, SD = 2.69, Range = 10.50). Figure 2 identifies a greater variance in the distribution of literacy scores for Tel Aviv students compared to Ariel students. An independent samples t-test revealed no significant difference in political literacy between the two universities, t (183) = -1.59, p (two-tailed) > .05. In addition, the distribution of literacy scores was assessed across each university running individual onesample t-test which stipulated there was no skew for Tel Aviv, t (94) = 1.062, p (two-tailed) > .05; or Ariel University, t (89) = -1.20, p (two-tailed) > .05. This means that although Ariel University College and Tel Aviv University differ in political attitudes, they are pretty similar in political literacy.

Testing predictions

Motivated reasoning on the other hand, predicts that people, who possess a liberal political stance, would be motivated to overweight information that is compatible with their political attitude and underweight evidence in favour of a conservative stance. Similarly, a person who subscribes to a conservative paradigm would be motivated to perceive information that corresponds to their political attitude and to dismiss evidence that is contradictory. Motivated reasoning would therefore postulate that as political literacy increased, political attitudes will become increasingly polarizes and more extreme. An initial assessment of political literacy and political attitudes identified a significant negative correlation between the variables, (r = -.153, p (twotailed) = .037, R2 = .023), which demonstrated a convergence towards conservative attitudes as political literacy increased.

This result is in fact in line with predictions of Motivated Reasoning, which suggests that as people encounter new information, they overweight information that is congruent and underweight incongruent information. Motivated Reasoning posits that extreme attitudes should be associated with increased literacy regardless of which political side an individual is on. As such Motivated Reasoning suggests that people become more extreme in their attitudes as they encounter more congruent information. To investigate, a linear regression was conducted using “Extremeness” as a dependent variable, characterised by absolute deviations of responses from the mid-point of the attitudes scale. Political attitudes, literacy scores and an interaction effect of attitudes and literacy were used as predictors, culminating in the equation below:

Political attitudes were into three groups, left-wing (n = 79), central (n = 33) and right-wing views (n = 73). A linear regression using heteroskedastic robust standard errors demonstrated a significant model (R2 = .209, F (3, 181) = 15.02, p < .001), where ‘Knowledge’ was a significant predictor (β = .116, p < .001), while ‘Attitudes’ (β = .433, p = .077) and the interaction term ‘Knowledge*Attitude’ (β = -. 035, p = .129) were insignificant predictors. These findings are consistent with Motivated Reasoning, extreme attitudes are best predicted by the amount of knowledge one possesses regardless of which political stance they take. This relationship is identified by the lack of significant by both Attitudes and the interaction effect. (Foot note 2)

Motivated reasoning theory posits that people who are coming from the conservative society (study at the Ariel University) are expected to vote to the right if they are more politically literate, but people who are coming from the liberal society (study at the Tel Aviv University) are expected to vote to the left if they are more politically literate. Therefore, Motivated Reasoning was able to predict relationships between political literacy and attitudes. Also, an increase in literacy was associated with a significant shift towards liberal views (r = - .334, p (two-tailed) = .001, R2 = .111), whilst the relationship was the reverse was demonstrated at Ariel University, an increase in literacy was associated with a shift, albeit marginally significant, towards conservative attitudes (r = .193, p (two-tailed) = .068, R2 = .037). These findings are also concurrent with predictions of Motivated Reasoning.

Overall, Motivated Reasoning successfully predicted outcomes within the data. There was a general shift towards liberal views overall as literacy increased. But an in-depth analysis revealed that people’s attitudes became more extreme, regardless of their political stance. With the effect being more prominent amongst liberal attitudes than conservative.

SEM Model

Separate SEM analyses were conducted for the interaction of political involvement, political interest, political literacy and political attitudes across Tel Aviv and Ariel University. These results supported Motivated Reasoning predictions as they illustrate the influence political literacy has on political attitudes and voting behaviour. In addition, the model also demonstrates how political involvement and political interest mitigate political literacy.

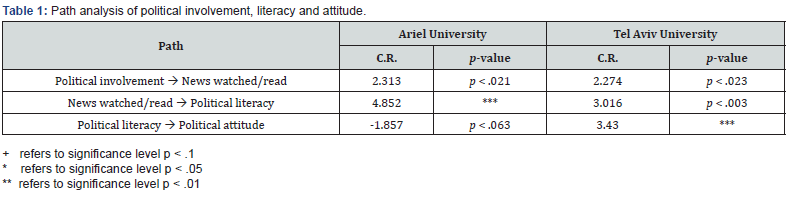

Table 1 identifies significant predictors for the political attitudes in both universities. In this Table, CR stands for critical ratio, which is the test statistic for each relationship. It is calculated by dividing the unstandardized estimate by the standard error and is similar to the t -statistic. The results identify significant causal relationships between numerous factors, which are significant across both universities. At Tel Aviv and Ariel, political involvement significantly influenced the amount of news that was watched or read by participants. High political involvement was associated with more news read and watched by participants from both academic institutions. The amount of news read or watched affected significantly political literacy scores in both Tel Aviv and Ariel. The more news participants read the better their political literacy was. Political literacy scores influenced political attitudes at Tel Aviv, and at Ariel University, however, this influence appeared in different direction. This relationship was significant only in Tel Aviv, in Ariel it was marginally significant. For Tel Aviv University: χ2 (3) = 7.035, p < .07; RMSEA=.120 p < 0.126; while for Ariel University: χ2 (3) = 18.166, p < .000; RMSEA = .238 p < 0.002.

Figure 3 presents a SEM analysis representing the relationship between political involvement and political attitudes in the rightwing Ariel University and in the left-wing Tel Aviv University as obtained using AMOS statistical addition to SPSS package. Overall, the results of the studies supported our hypotheses, that people who were predisposed by their residence or background to the right/left political wing show greater political extremity the more they are involved in politics. A-priori political involvement influences the amount of political information one gets on the news. The more information one receives the more politically literate he or she becomes. But since the choice of the information, its perception and apprehension are influenced by motivated reasoning, the more (one-sided) information one gets the more extreme he or she becomes in the political attitude. The political literacy influenced the voting decision towards the right and left, the negative coefficient for Tel Aviv predicted a vote towards the left; whereas political literacy in Ariel, depicts a prediction for voting towards the right, as illustrated by the negative value which asserts the direction of a conservative political attitude in the leftright dichotomy.

Discussion

Our results evaluated the predictions of Motivated Reasoning and replicate Taber and Lodge [26] seminal findings in a novel, politically-charged context (Israel, the Middle East), using a field study approach (sampling across two cities with opposing political views). The results collected suggest that the relationship between political literacy and political attitudes is not linear, but instead is bimodal, as attitudes become more extreme as literacy improves. The results suggest that Motivated Reasoning can explain the polarisation of political attitudes. As the public becomes increasingly politically literate, they form beliefs predisposed by their current attitudes, becoming increasingly extreme in these given beliefs. It is likely that individuals do not reach a common consensus based solely upon the information presented to them, they instead form evaluate the information such that it satisfies their interests. A recent survey by Pew Research Centre [17] stipulated a similar effect as demonstrated by our findings. The survey shows that political attitudes in the US become more extreme over time: American voters have become increasingly polarized over the recent years, and this could be the result of motivated reasoning. Conservatives have become increasingly more extreme and right-wing than previous generations: for instance, 30% of Democrats considered themselves as liberal in 1994, where 5% of Democrats considered themselves as consistently liberal. However, these figures shot up to 56% in 2014, with 23% self-identifying as consistently liberal. Meanwhile 45% of Republicans considered themselves conservative in 1994, with 13% as consistently conservative; whilst 53% of Republicans identified themselves as conservative in 2014, with 20% labelling themselves as consistently conservative. These upwards trends outline a shift towards more extreme views, from central views towards mostly liberal or conservative, and further again from mostly left or right-wing attitudes to consistently left or rightwing. As such these trends described are identical to those presented in this paper, suggesting the role Motivated Reasoning may play in the polarization of political attitudes. (Foot note 3)

These trends stipulate how political attitudes bias information evaluating processes and as such how these biased evaluations reinforce and intensify political attitudes. One component of motivated reasoning is invariably to discount opposing evidence in contrary to a given belief [46,47], for example, a climatechange denier would underweight evidence in favour of climate change [48-50]. Moreover, as people are driven by their beliefs, becoming more politically extreme, as an individual becomes more extreme, whether to the left or right, they would overweight the threat of an opposing belief or idea [51,52]. This paper aimed to investigate the relationship between political literacy and political orientation. Our results suggest political involvement, interest and literacy may shape political attitudes. Those with higher political literacy held more extreme political attitudes, both to the right at Ariel University and to the left at Tel Aviv University. This result is consistent with motivated reasoning. The results suggest that peoples’ beliefs and values motivate them in becoming increasingly extreme leading the left more liberal, and the right more conservative.

The results could have important considerations for political issues. Debates over important civil and political issues that drag on could face political divide, which would lengthen the legislative process. For example, gun control legislation has seen disruption in the US Senate in 2013, lengthening the bill passage [53]. Our results suggest that this disruptive behaviour is a result of attitude polarization brought on by motivated reasoning, political interest and political literacy. Our findings imply that political literacy and political interest could both directly influence political attitudes, although this raises certain questions. How can political polarization be reduced? Reducing political polarization has important implications in the context of civil rights, for example divide over issues such as abortion can fast become debates on who has control over woman’s reproductive rights [54-62]. Therefore, reducing political polarization can help to stabilise debates and to reduce the explosive fallout associated. Would making political information more readily available sway political attitudes? Those are important open questions for future research [63-68].

In summary, these findings illustrate that a person’s political orientation is partly determined by their political literacy and interest. As their political literacy increases people do not formulate correct responses, but instead are biased by their own beliefs becoming more extreme. This research provides an initial look into how political literacy might influence political attitudes, and how cognitive processing biases political attitudes. In doing so, it suggests that cognitive processing can influence areas of our beliefs with important and surprising outcomes [69,70].

Ethical Compliance Section

Funding: The authors have no funding to disclose.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual adult participants included in the study.

Appendix A

Questionnaire Used in the Study

The following questionnaire is designed to assess the level of your erudition in Israeli politics. Please, answer the following questions:

1. Who is the Minister of Health? ___________________________________________

2. Who is the Minister of Finance? __________________________________________

3. Who was the first president of Israel? ______________________________________

4. Who was the second Prime Minister of Israel? _______________________

5. Explain briefly what the meaning of “mehapah” is and when it happened? _________________________________________________________________ __________

___________________________________________________________________________6. What is the year of the establishment of Israel?________________________________

7. In what year Itzhak Rabin was murdered? __________________________________

8. Explain briefly what the meaning of “Lavon Affair” is? ____________________

_____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________9. Explain briefly what the meaning of “mandate” is: _____________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________10. Has the State of Israel a constitution? Yes / No

11. Explain briefly what the meaning of “Basic Law of Human Dignity” is? _____________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________

12. Explain briefly what the meaning of “kitchenette” is? __________________________

______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________13. Which parties joined together to assemble the Labor Party?

___________________________________________________________________________14. Which parties joined together to assemble the Likud Party?

___________________________________________________________________________15. Who is the spiritual leader of the Shas Party? __________________________

_____16. Explain briefly why the Kach Party was disqualified from Parliament? _____________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________

News coverage

1. How often you are watching the evening news?

A. Several times a day

B. Several times a week

C. About once a week

D. Less than once a week

E. I don’t watch TV at all

2. How often you are reading the news in the newspapers?

A. More than once a day

B. Several times a week

C. About once a week

D. Less than once a week

E. I don’t read newspapers at all

3. How often you are reading the news on the internet portals?

A. More than once a day

B. Several times a week

C. About once a week

D. Less than once a week

E. I don’t have internet access at all

4. Have you read or watched the news yesterday? Yes / No

Political involvement

1. Are you a member of any political party? Yes /No

2. Please, rate your political involvement on the scale from 1 to 5:

Which party would you vote for suppose the elections were taking place right now: _______________________________________________

Demographic questions

Gender: 1. Man 2. Woman

Year of birth ________

Level of education ________

References

- Whitman WB (2003) The Quotable Politician. The Lyons Press, Guilford, Connecticut, United States.

- National Geographic (2006) National Geographic - Roper Public Affairs 2006 Geographic Literacy Survey. Education Foundation. [Report]. Washington: GfK Roper Public Affairs 1-65.

- Kahan DM (2013) A risky science communication environment for vaccines. Science 342(6154): 53-54.

- Pew Research Center (2012) More say there is solid evidence of global warming. Pew Research Centre.

- Stocker TF, Dahe Q, Plattner GK (2013) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers (IPCC, 2013).

- Drake F (2000) Global Warming-The Science of Climate Change. Oxford University Press, United Kingdom.

- Gore A (2006) An inconvenient truth: The planetary emergency of global warming and what we can do about it. Rodale.

- Root TL, Price JT, Hall KR, Schneider SH, Rosenzweig C, et al. (2003) Fingerprints of global warming on wild animals and plants. Nature 421(6918): 57-60.

- Hughes I (2000) Biological consequences of global warming: is the signal already apparent?. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 15(2): 56-61.

- Oppenheimer M (1998) Global warming and the stability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Nature 393(6683): 325-332.

- Karl TR, Knight RW, Baker B (2000) The record breaking global temperatures of 1997 and 1998: Evidence for an increase in the rate of global warming?. Geophysical Research Letters 27(5): 719-722.

- Abu-Asab MS, Peterson PM, Shetler SG, Orli SS (2001) Earlier plant flowering in spring as a response to global warming in the Washington, DC, area. Biodiversity & Conservation 10(4): 597-612.

- Mooney C (2006) The Republican war on science. Massachusetts Basic Books, Cambridge, England.

- Cooper R (2012) Rise of the Greek neo-Nazis: Ultra-right party Golden Dawn wants to force immigrants into work camps and plant landmines along Turkish border. Daily Mail.

- Morris N (2015) General Election 2015: Immigration - how the parties are playing the numbers game. The Independent.

- Wilkinson M (2015) Election 2015: NHS party policies. The Telegraph.

- Pew Research Centre (2014) Political Polarization in the American Public How Increasing Ideological Uniformity and Partisan Antipathy Affect Politics, Compromise and Everyday Life. Pew Research Centre.

- Hastorf AH, Cantril H (1954) They saw a game; a case study. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 49(1): 129-134.

- Young AI, Ratner KG, Fazio RH (2014) Political attitudes bias the mental representation of a presidential candidate’s face. Psychological Science 25(2): 503-510.

- Redlawsk DP (2002) Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. The Journal of Politics 64(4): 1021-1044.

- Sharot T (2011) The optimism bias. Current Biology 21(23): 941-945.

- Kunda Z (1987) Motivated inference: Self-serving generation and evaluation of causal theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53(4): 636-647.

- Lebo MJ, Cassino D (2007) The aggregated consequences of motivated reasoning and the dynamics of partisan presidential approval. Political Psychology 28(6): 719-746.

- Slothuus R, De Vreese CH (2010) Political parties, motivated reasoning, and issue framing effects. The Journal of Politics 72(3): 630-645.

- Kahan DM (2013) Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making 8(4): 407-424.

- Taber CS, Lodge M (2006) Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science 50(3): 755-769.

- Cohen GL, Sherman DK, Bastardi A, Hsu L, McGoey M, et al. (2007) Bridging the partisan divide: Self-affirmation reduces ideological closed-mindedness and inflexibility in negotiation. Journal of personality and social psychology 93(3): 415-430.

- Lord CG, Ross L, Lepper MR (1979) Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37(11): 2098-2109.

- Nickerson RS (1998) Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology 2(2): 175-220.

- Forer BR (1949) The fallacy of personal validation; a classroom demonstration of gullibility. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 44(1): 118-123.

- Pompian M (2006) Behavioral finance and wealth management. (1st Edtn). Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, United States.

- Smith JC (2009) Pseudoscience and Extraordinary Claims of the Paranormal: A Critical Thinker's Toolkit. John Wiley and Sons.

- Randi J (1991) James Randi: psychic investigator. Boxtree, London, United Kingdom.

- Meffert MF, Chung S, Joiner AJ, Waks L, Garst J (2006) The effects of negativity and motivated information processing during a political campaign. Journal of Communication 56(1): 27-51.

- Kahan DM, Braman D, Slovic P, Gastil J, Cohen GL (2009) Cultural Cognition of the Risks and Benefits of Nanotechnology. Nature Nanotechnology 4(2): 87-90.

- Kahan DM, Braman D, Cohen GL, Gastil J, Slovic P (2010) Who fears the HPV vaccine, who doesn’t, and why? An experimental study of the mechanisms of cultural cognition. Law and Human Behavior 34(6): 501-516.

- Kahan DM, Braman D, Monahan J, Callahan L, Peters E (2010) Cultural cognition and public policy: the case of outpatient commitment laws. Law and Human Behavior 34(2): 118-140.

- Kahan D (2012) Why we are poles apart on climate change. Nature 488(7411): 255.

- Tedin KL (1974) The influence of parents on the political attitudes of adolescents. American Political Science Review 68(4): 1579-1592.

- Kanai R, Feilden T, Firth C, Rees G (2011) Political orientations are correlated with brain structure in young adults. Current Biology 21(8): 677-680.

- Oswald ME, Grosjean S (2004) Confirmation bias. In: R F Pohl (Ed.). Cognitive Illusions: A Handbook on Fallacies and Biases in Thinking, Judgement and Memory. Psychology Press, United Kingdom.

- Taber CS, Cann D, Kucsova S (2009) The motivated processing of political arguments. Political Behavior 31(2): 137-155.

- Benn A (2010) Tel Aviv liberals are true Israelis too. The Guardian.

- Greenfield D (2014) Israel Student Union Protests Obama’s Exclusion of Conservative Students.

- Madlan, (2014) Madeleine. Madlan.

- Green DG (2014) The Eye of the Beholder. In: Of Ants and Men. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Legoux R, Leger PM, Robert J, Boyer M (2014) Confirmation Biases in the Financial Analysis of IT Investments. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 15(1): 33-52.

- Hoggan J, Littlemore RD, Ball T (2009) Climate cover-up: The crusade to deny global warming. Greystone books, Canada.

- Shermer M (2010) I am a sceptic, but I'm not a denie. New Scientist 206(2760): 36-37.

- Washington H (2011) Climate change denial: Heads in the sand. Routledge.

- Inbar Y, Pizarro DA, Bloom P (2012) Disgusting smells cause decreased liking of gay men. Emotion 12(1): 23-27.

- Taylor K (2007) Disgust is a factor in extreme prejudice. British Journal of Social Psychology 46(3): 597-617.

- Fram, A. (2013) Gun Control Measures Taken Up By Senate Committee. Huffington Post.

- Winter M (2014). Federal judge voids key piece of Texas abortion law. USA Today.

- Dawes RM (1990) False Consensus Effect. Insights in decision making: A tribute to Hillel J. Einhorn p.1-179.

- De Sousa R, Morton A (2002) Emotional Truth. The Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume 76(1): 247-275.

- Dimitrov Y, Vazova T (2020) Developing Capabilities From the Scope of Emotional Intelligence as Part of the Soft Skills Needed in the Long-Term Care Sector: Presentation of Pilot Study and Training Methodology. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 11.

- Dimotrov Y, Vlaev I (2015) Corporate training in emotional intelligence: Effective practice or modern ‘fugazy’. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 7: 70-79.

- Dearborn DC, Simon HA (1958) Selective perception: A note on the departmental identifications of executives. Sociometry 21: 140-144.

- Delavande A, Manski CF (2012) Candidate preferences and expectations of election outcomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(10): 3711-3715.

- Dennis PA, Halberstadt AG (2013) Is believing seeing? The role of emotion-related beliefs in selective attention to affective cues. Cogn Emot 27(1): 3-20.

- Ditonto TM, Hamilton AJ, Redlawsk DP (2014) Gender Stereotypes, Information Search, and Voting Behavior in Political Campaigns. Political Behavior 36: 335-358.

- Dunwoody S, Griffin RJ (2014) The Role of Channel Beliefs in Risk Information Seeking. In: Effective Risk Communication. Eds. Joseph Arvai and Louie Rivers III. Taylor & Francis (Routledge) London., United Kingdom pp.220-233.

- Kida TE (2006) Don't believe everything you think: The 6 basic mistakes we make in thinking. Prometheus Books.

- Kunda Z (1990) The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin 108(3): 480-498.

- Kunda Z (1999) Social cognition: Making sense of people. MIT press. .

- Kunda Z, Fong GT, Sanitioso R, Reber E (1993) Directional questions direct self-conceptions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 29(1): 63-86.

- Lodge M, Taber C (2000) Three steps toward a theory of motivated political reasoning. Elements of Reason: Cognition, Choice, and the Bounds of Rationality 183-213.

- Shafir E (1993) Choosing versus rejecting: Why some options are both better and worse than others. Memory & Cognition 21(4): 546-556.

- Sherrod DR (1971) Selective perception of political candidates. Public Opinion Quarterly 35(4): 554-562.