Measurement of Love, Quality and Quantity: A thousand kisses deep”

Michael G King*

Sunshine Specialist Centre, Australia

Submission: September 14, 2019; Published: November 01, 2019

*Corresponding author: Michael G King, Sunshine Specialist Centre, 429 Ballarat Rd, Sunshine, Victoria, Australia, 3020

How to cite this article:Michael G King. Measurement of Love, Quality and Quantity: A thousand kisses deep. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 13(5): 555871. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.13.555871

Abstract

A clinical measurement of love is condensed from extant love models and metrics to a practical methodology combining the contributions of cognitive and personality factors, as well as attachment style. In line with the conservative imperative that behoves psychological opinion to be evidence based, the Bowlby-style attachment basis of romance is operationalized through extension of the six colours of love, the interaction of cognitive functionality with love style is acknowledged, and a personality analysis of both parties to the self-proclaimed love affair are combined to provide the external observer with a tangible profile of any romance. As well as contributing to clinical involvement in des Affairs de Coeur, the formal evaluation of love profile provides substance for the Expert Clinical Opinion requirement generated by current immigration-based matters. Representing a clinical application for historically developed tools of love audit, the resulting evaluation is

i. Credible (meaning that it is generally comprehensible to other than psycho-amoretic-metricians and has a viable level of face validity) and

ii. Founded on the psychologist’s canon of established assessment processes. A case study and resulting Expert Clinical Love Report illustrates the method.

Keywords: Love; Measurement of Love; Romance; Romantic attachment; Adult Attachment; Immigration; Forensic Psychology; Personality.

Introduction to love

For the psycho-metrician it is the tacit assumption that if we can talk about a condition, and certainly if we can admit to there being more or less of the target quality (even if the descriptive terminology be florid and appear at first glance defy numerical categorization), it is inevitable that the use of relative or ranking descriptors generates the expectation that stochastic quantification is only a or two step away. The present paper seeks to advance beyond the poetic volumetric estimation of love in imprecise units such as “a thousand kisses deep” [1], to consider the formal love studies of the last half a century or so, and to derive a clinically useful measurement process. To provide clear focus, the current paper specifically seeks to serve a developing clinical/forensic issue – the validation of a self-proclaimed union as “true love” or otherwise.

Forensic Lovet

Although there always has been a recognition of “love” among the rule-making and behaviour-managing jurisdictions (including both ecclesiastical and lay) the primary involvement of the law has been to proscribe particular categories of emotional attraction and bonding, with the target forbidden activities most commonly being sexual or pre-sexual encounters. What is permitted in public or in private, and with whom (or with what) these behaviours may legitimately be carried out, has been the core of romance-focussed legislation. Heretofore the legal system has not been interested in how strongly a person felt attracted to another, and the law has not been asked to make potentially precedent-creating decisions on the positive aspects of love, nor to seek evidence-based opinions on such issues: is love present here at all; and if so how strong; or how “real” or genuine is this love? Indeed, until recently such ponderings have not been the fodder of case law.

With the world-wide trend towards tightening of immigration policy in countries which are perceived as economically or socially desirable, there has been a parallel rise in efforts to thwart border protection measures. Apart from clandestine incursions at remote or unsupervised segments bounded by the perimeter of sovereignty, an attractive gap in the policy wall facing the would-be immigrant is the superficially reasonable proposition that love and then marriage confers upon one partner the national allegiances and citizenship of the other. Unsurprisingly the efforts to assert this “superficially reasonable” implication has generated instances of spurious and falsely proclaimed romances as a virtual people smuggling strategy. These invented love affairs are understood to be outside the umbrella of romantic attachment, and it follows logically that to complement effective physical border protection and the implementation of immigration policy there will arise the need for appropriate tools to weigh these proposed relationships in the balance, and to embrace those unions which reflect genuine love, or, where the quantity of love falls short, to be cast out into the visa-devoid darkness where there may be wailing and the gnashing of teeth.

The charter to scrutinize couples in search for convincing evidence of “true love” has generated the need for Expert Opinion from professionals whose specialist knowledge base covers an understanding of emotional states – and that would include the Clinical Psychologist. Recognising the need for advice on the romantic underpinning of professed relationships, it is important to remember that the legal validity of such Expert pronouncements has been the subject of musings by the Law Lords: clinical psychological opinions are not derived from “thought experiment” but, au contraire, must be based upon “certain well known tests”1. Thus a chain of events which began with a flood of uncontrolled migration and ends with marriages of convenience poses for the clinical psychologist the need to acquire tools selected from the canon of “certain well known tests” in order to achieve the potential for admissible (and more importantly valid) opinion about love.

Whether or not judicial precedential weight is conferred to the Privy Council, it surely provides an informative if not binding view and it also matches up with common sense to rely upon a psychological opinion which rests upon the conservative base of “certain well known tests”, rather than an interpretation derived from a process which is bereft of the tangible evidence.

Psychometric Love

There is ample evidence in romantic literature bases to indicate that something special can happen between two adults. “For centuries, romantic love has been explored by writers and philosophers who have revealed multiple emotions and feelings” ([2] pp. 675) and by midway through the last century, social scientists began work on the task of “defining love conceptually and operationally.” (ibid, p. 676). The separation of some nominated domain of human functioning into (more or less) independent components has been an evolving theme within social science research, and the half a dozen “colours of love” distinguished by Lee [3] were subsequently transformed [4] to a hexagonal factor-analytic solution defining separable love dimensions which combine to describe different profiles of romantic union. These love profiles allowed for the presence, or absence, of components other than the Hollywood model: descriptions equating to a shopping

list approach, or to a compelling form of neurotic subservience could be classified as valid exemplars of romantic union. Despite their denunciation as blaspheming against the mythological experience of “true love”2, these two contributors (that is, Lee and the Hendrick dyad with their six factors) to love measurement can be recognised in hindsight as having landmark status in the science of love-metrics [5]. Their acknowledgement is all but mandatory in any contemporary study of love: the Hendrick & Hendrick oeuvre had achieved near 1000 cites by 2016. However, not unlike the ongoing discovery of new, even smaller sub-atomic particles, to acknowledge the 6-factor model goes hand in hand with the uncovering of multiple new (tinier) love fragments. A recent study of love distinguished a heart-stopping 33 aspects (potentially factors?) of love [2], with the primary importance of that investigation being not so much the number of love shards, but more the expectation of reducing the fragments of evidence by some sort of grouping process “Deeper exploration of the clustering of these dimensions will help our better understanding of implicit models of love” (ibid, p 697).

Mental Complexity (MC)

Even more useful was the Karandashev & Clapp [2] announcement that the individual’s “Mental Complexity” (MC) may determine the trajectory of their of romantic experience. From analysis of love narrative, the expectation of a coherent and rational profile among those of high MC is contrasted with proposition of a love experience which is, at first glance, “irrational” for lovers of lesser cognitive capacity:

i. [compared to] people with high and medium mental complexity, . . . people with low mental complexity . . . distinguish [love] dimensions differently......

ii. People with high mental complexity.... tend to perceive the love dimensions more logically, consistently, and sensibly than people with lower mental complexity. (p 680)

iii. For medium and higher mental complexities, the dimensions [of love] appear closer and more coherent.

iv. Those with lower mental complexity displayed the opposite: many small clusters, isolated dimensions, and illogical patterns in clusters....

v. In low mental complexities, dimensions are rather.... inconsistent .... the dimensions of Irrationality, Possession, and Obsession emerged

vi. And speaking directly to dimensions that are distinguished by attachment models of love. Low mental complexity is.... related to the dimensions of attachment anxiety, possession, and elation” ([2] pp. 694).

Anticipating, in the forensic setting, the assessment of a professed relationship style which deviates from the narrow experience which forms the idealised romantic attachment of Mathes [5], it is now evident that information about this quality of MC is necessary before the dichotomous Expert Opinion (credible/genuine love, or not) can be delivered. Although the Karandashev & Clapp [2] notion of MC drew upon content analysis of narrative, for the Clinical Psychologist, the core MC assessment tool is the adult IQ (for example the Wechsler WAIS-IV). However, it is (almost by definition) the case that for immigration/visa relevant love, the most informative index of MC may not equate to the somewhat academically slanted evaluation of intellect which is represented by the unadorned IQ composite score. In fact, for immigration cases, many of the sub-tests on the standard Wechsler suite would be partially or fully opaque due to language, educational experience, and cultural factors. Leaving the choice of source data as broad, and at the same time as appropriate as possible, the present model seeks to stand distant from core IQ and thus expresses the outcome of MC as a T-score3.

For the purpose of love, it is the present model that romance- relevant MC should at least begin by considering Scaled Scores from the adult IQ (WAIS) battery. More than providing a measure of overall “mental strength”, the WAIS suite of sub-tests has over the years and been interpreted as giving an indication of cognitive functionality in social situations, and the putative social- cognitive quality is arguably in line with the present [2] notion of MC in romantic interactions. Allen & Barchard [6] review the almost century-long contention, dating back at least as far as Thorndike’s search for factors that would reflect the human capacity to “understand, interact with, and manage others” (ibid , pp. 263) that a comprehensive cognitive measurement will include a component which relates to “social cognitive abilities [which] are an integral feature of global [intellectual] capacity” (ibid, p 272). By the end of the last century, credible and consistent factor analysis had distinguished a Social Cognition construct which was composed of (at least) the Wechsler subtests of Picture Arrangement (PA) and Picture Completion (PC). Although at first glance providing a measure of something akin to knowledge about society and perhaps social-cognitive strength, the verbally delivered Comprehension subtest has consistently shown relatively weak loading on this putative Social Cognition (SC) factor. Although the Allen & Barchard [6] analysis supported the inclusion of an additional performance task, Object Assembly (OA) as a contributor to the estimation of social functionality, a roughly parallel previous investigation [7] found support for only PA and PC as estimates of the underlying SC trait. In summary, where the target of a cognitive function has a clear component of social understanding, albeit headed with a generalist-seeming label (“mental complexity”), then the two subtests PC + PA are arguably the first choice - and this choice is all the more appropriate when language difficulties are present. The knowledge that occasionally aberrantly high scores can occur on any single sub-test would encourage the selection of at least three measures to provide a more reliable estimate of MC.

The selection of a third sub-test could come from the following:

i. Other WAIS score, with preference (where language is not a barrier) for Comprehension, and less enthusiasm for the technical tasks of Matrix Reasoning or Block Design where these may differ from the putative socially relevant MC quality being assessed. Where multiple IQ sub-tests have been completed (for example the full set of 10 or 12) it is suggested that a potential MC score be computed on the lowest three sub-tests, and another candidate on the highest three. This approach gives the clinician the responsibility of exercising clinical judgement as to which of the potentially disparate MC scores will have relevance to the computed attachment scores4

ii. From sub-tests of the Delis Kaplan Executive Function suite, any test demonstrating planning capacity (Tower Test, which is language free), tendency to become confused in complex situations (Color Test, which may be available in appropriate translations), or 20 questions (to illustrate the client’s capacity to infer what the other person is has in mind)

iii. A social functionality score based upon sub-domains of the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales.

The report should emphasize that in the context of a romantic union the computed Mental Complexity score is not necessarily identical to full scale IQ score.

Personality

Equally valuable as MC in the sense of having the demonstrated potential to explain variance in love measures was the contribution of Sperling [8] confirming the tautological proposition that personality type interacted with the experience of love: “.... people can be differentiated in their experience of . . . love based upon . . . characteristic qualities of self .... “([8] pp. 324). It appears easy to recognise as self-evident the value of a Sperling-derived use of personality as a lens through which to view the love experience, however this assessment strategy did not become the standard. Although the need to take “characteristic qualities of self” into account continues to be tacitly recognised (for example: “dispo-sitional tendencies to experience.... love and compassion—emotions that have well-documented and robust influences on prosocial responding” ([9] pp. 887)), over the three or more decades since Sperling the measurement of love has in the main left out of consideration the interpersonal functional variables of personality or the contribution of MC.

Although not unique in the provision of personality measurement, the long-standing 16PF is the selection favoured by the present model, since this tool provides bi-polar scores for several relevant interpersonal qualities. For coherence with all scores reported in the ensuing forensic summary, the 16PF scales are reported as T-scores, as will be seen in the case study appended.

Attachment Models of Adult Love Speaking to early human emotional interactions, Bowlby (for example see Bretherton [10]) refined to an enduring model the classification of emotional infant bonding with their caretakers. Attachment theory describes (at least5) three categories of relationship: Secure, Avoidant, and Anxious-ambivalent. The distribution of these attachment styles (both child: mother and adult-romantic) is consistently reported as being around 2:1:1 for secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent (e.g. [11,12]). And essentially the same Bowlby attachment labels emerged from a quite recent meta-analysis of love scales: general love (an enduring, effectively secure relationship), romantic obsession (a more fragile anxiety-related style), and practical friendship (conceptually avoiding exposure to commitment of the heart) emerged [13].

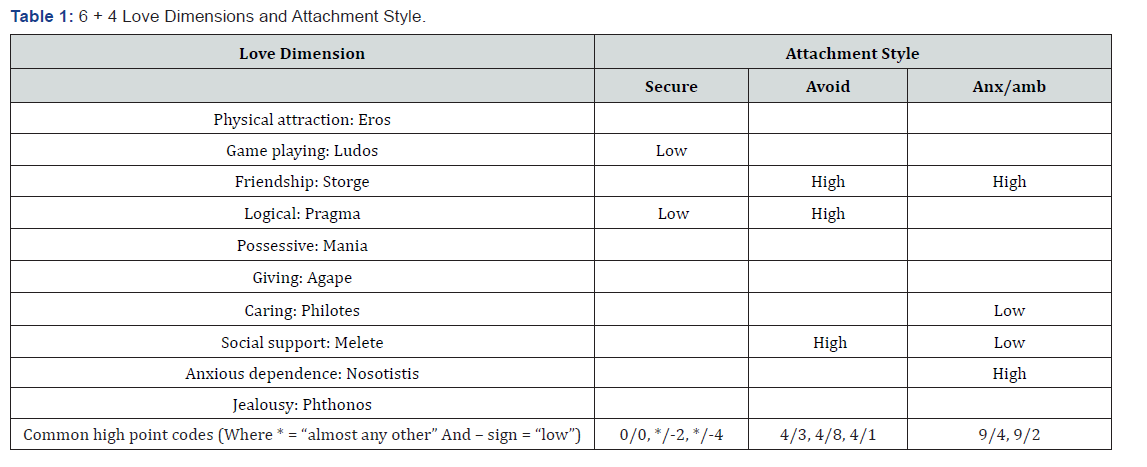

The current model evaluates Attachment style, using a 75- item love questionnaire, King (1991) developed from the benchmark love and adult attachment studies [4,11,12,14], and yielding a Bowlby-based attachment analysis of love style. This tool evaluates ten bipolar factors of love which indicate attachment style (Table 1).

Summary of Love

Love measurement research has been conducted under the questionable (and indeed occasionally questioned) assumption that a meaningful answer to the question “what sort of love do you experience” can be discovered in the absence of any evidence about “what sort of person are you”. Furthermore, the question as to “why” (in the sense “to serve what purpose”) are we measuring romantic love has never been a guiding focus. Although attachment theory, personality and mental complexity have been credibly raised as important factors defining the love experience, at least one impediment to arriving at a consensus on the general methodology nor on the “best” instruments to evaluate romance has been the absence of a unifying, focussing reason for the evaluating the love experience. Indeed, the difficulties of deciding how to conceive of love precede the impediments to the confident measuring of this experience, and this fundamental definitional complexity is illustrated by the opacity of the following: The idea of love as a salutogenic agent is just one possible approach to the epidemiology of love. By no means does it exclude consideration of love as a psychosocial host factor .... love may be considered both as an agent and a host .... [15]. Acknowledging the conceptual quagmire of amoretic assessment, a recent meta-analyses of love measures [16] concluded that something more than an array of love questions is necessary to make sense of the data, asserting “the need for measurement methods other than global self-report [that is, self-report on the love experience itself]” (Graham, 2011). And almost as a self-defeating prophesy, the prospect of finding a useful measure does indeed appear daunting when the target is something as grand as that envisaged by Graham [13] (pp. 765): Romantic relationships are what many consider an important part of what it means to be human. In many Western cultures, love is seen as an essential component (if not the most essential component) of a successful romantic relationship. Therefore, a well-developed understanding of love is highly important to understanding how and why relationships last and fail.

The attempted measurement in the vacuum of specific need is to produce a “solution looking for a problem”, as the laser was once described [17]. Thus, the decades of investigation, although lacking focussed coherence have provided the laser-like solution which can be applied to the singular issue of forensic love. Contrasting with the search for global factors affecting the long-term durability of a romantic coupling, the present strategy (Table 2), employs certain well-known tests to satisfy a quite specific need: the legal requirement of providing an Expert Opinion which speaks to the credibility of a professed romantic relationship.

Anticipating further developments in the forensic quantification of love, and inspiring optimism in the prospect of success in the search for the ideal forensic metric for les Affairs de Coeur, consider the words of a modern-day guru:

If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it.

(Steve Jobs, 2005 Stanford Commencement Speech)

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (5th edn.), American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries 63: 1-21.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (2018) National Institutes of Mental Health, United States.

- van Steensel FJA, van Bögels SM, Perrin S (2011) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A metaanalysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(3): 302–317.

- Mehtar M, Mukaddes NM (2011) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in individuals with diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 5: 539-546.

- De Bruin EI, Ferdinand RF, Meester S, de Nij PFA, Verheij F (2007) High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in PDD-NOS. J Autism Dev Disord 37(5): 877-886.

- Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, Lewin AB, Arnold EB, et al. (2013) The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Develop Disord 43(10): 2450-2459.

- Dell’Osso L, Dalle Luche R, Carmassi C (2015) A new perspective in post-traumatic stress disorder: Which role for unrecognized autism spectrum. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 17(2): 436-438.

- Nietlisbach G, Maercker A (2009) Social cognition and interpersonal impairments in trauma survivors with PTSD. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma 18(4): 382-402.

- Kerns CM, Newschaffer CJ, Berkowitz SJ (2015) Traumatic childhood events and autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 45(11): 3475-3486.

- Stavropoulos K, Bolourian Y, Blacher J (2018) Differential Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Two Clinical Cases. J Clin Med 7(4).

- Trelles Thorne Mdel P, Khinda N, Coffey BJ (2015) Posttraumatic stress disorder in a child with autism spectrum disorder: Challenges in management. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25(6): 514-517.

- Morries LD, Cassano P, Henderson TA (2015) Treatments for traumatic brain injury with emphasis on transcranial near-infrared laser phototherapy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11: 2159-2175.

- Hamblin MR (2016) Shining light on the head: Photo biomodulation for brain disorders. BBA Clin 6: 113-124.