Combatting Childhood Obesity in An Australian Community Intervention: Do Goal-Setting and Incentives Encourage Healthy Eating and Exercise Behaviour Change?

Gemma Enright1,2, Alex Gyani3,7, Margaret Allman-Farinelli4, Chris Rissel5, Christine Innes-Hughes5, Sarah Lukeis6, Anthony Rodgers2, Lily Chen2 and Julie Redfern1,2*

1Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Australia

2The George Institute for Global Health (Cardiovascular Division), Australia

3NSW Department of Premier and Cabinet, Behavioural Insights Team, Australia

4Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, Australia

5 Ministry of Health, NSW Office of Preventive Health, Australia

6The Better Health Company, Australia

7 Behavioural Insights Team, Australia

Submission: March 23, 2019; Published: April 23, 2019

*Corresponding author: Julie Redfern, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, The George Institute for Global Health (Cardiovascular Division), The University of Sydney at Westmead Hospital, PO Box 154 Westmead NSW 2154, Australia

How to cite this article: Julie R, Gemma E, Alex G, Margaret A-F, Chris R, et al. Combatting Childhood Obesity in An Australian Community Intervention: Do Goal- Setting and Incentives Encourage Healthy Eating and Exercise Behaviour Change?. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 11(3): 555813. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.11.555813.

Abstract

This research aimed to explore the contextual influences and behaviour change techniques on diet and exercise behaviours in overweight or obese children aged 7 to 13yrs. Qualitative methodology comprised 18 family interviews with families participating in an Australian community weight-management program during a cluster randomised controlled trial investigating goal-setting and incentives for enhancing healthy eating and exercise behaviours. Inductive thematic analysis and the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy guided analyses.

This research demonstrated that parents can have different approaches and levels of confidence in managing healthy behaviour in their families but share similar emotional struggles that inhibit healthy eating and exercise in the family. This evaluation, combined with existing psychological literature, supports the concept of creating autonomous accountability around goal-setting as the focus of future weight management programs, which is potentially imperative to long-term behaviour change. Future interventions targeting health-related behaviour change should aim to avoid controlling approaches that detract from participants’ sense of control, self-efficacy and support.

Keywords: Childhood-obesity; Public-health; Incentives; Behavior-change; Qualitative; Prevention

Abbrevations: BCT: Behavior Change Technique; cRCT: Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial

Introduction

Reducing childhood obesity is of increasing public health importance. In 2014, 41 million children under five years of age were estimated to be overweight [1] and being overweight as a child has been shown to carry a high risk of being obese as an adult [2] and accelerating the risks of associated conditions such as cardiovascular disease [3]. As such, public health services are integral in preventing and managing childhood obesity [4], and strategies informing interventions for health-related behaviour change in children are increasingly relevant at policy level. Systematic reviews investigating the effectiveness of child-focused behavioural interventions have indicated small positive outcomes on healthy eating and physical activity behaviours [5], however, facilitating behaviour change in obesity-focused public health initiatives is often challenging because people struggle to establish healthy habits they can sustain after the program [6]. This is despite evidence for specific behaviours required for effective weight-loss [7-12] and elements recognised as important to achieve long-term behaviour changes [7,12].

Evidence is mounting in adults for a role of incentives in enhancing health-related behaviour change in the short-term [13-20], but high heterogeneity across study designs, incentive strategies and outcome measures, and a lack of long-term follow up have prevented firm conclusions on the most effective incentive strategy for behaviour change. The studies also highlighted that existing incentive-based interventions in natural settings tend to lack grounding in basic behavioural theories. Preliminary evidence for incentives enhancing health-related behaviour change in children is encouraging, though sparse and low quality. A recent review [21] highlighted several (uncontrolled) studies that found positive results associated with incentivising health behaviours in children, with two studies reporting sustained effects at two months [22] and six months [23] follow-up. Several small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have used a combination of psychological strategies (such as peer modelling) and low value incentives to encourage behaviour change in children within primary schools to encourage exercise behaviour [24,25] and fruit and vegetable consumption [26,27]. These studies highlighted that incentive strategies shown to effectively influence multiple target behaviours short term may have varied effects longer term for those behaviours, and that differences can emerge by age, gender and socio-economic background [22,26]. Information on the social and environmental influences and behavioural mechanisms involved in health-related behaviour change is missing from existing research on child-focused incentive-based interventions in community settings.

RCTs are important for establishing the effectiveness of community-based interventions but are unable to provide policy-relevant information on how complex interventions work in context [28]. Conducting qualitative research alongside an RCT provides rich contextual information about what worked and did not work, the type of change that occurred, and the circumstances in which it was most and least effective and why [29-31]. Such information can inform strategies for specific child populations and facilitate adoption of intervention components into community health settings. This study aimed to determine the contextual factors and active behaviour change components influencing the behavioural outcomes of an incentive-based behaviour change strategy targeting child obesity.

Specifically, the research aimed to understand

i. Attitudinal characteristics of participating families;

ii. Factors influencing impacts of the strategy over 18-months

iii. Active behaviour change techniques in the strategy and links with psychological theory.

Material and Methods

Design

Qualitative research conducted in New South Wales Australia between 2014-2016 between the six and 18-month follow-up of an associated cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) [32]. In brief, the cRCT (n=512 children, 38 program sites, five local health districts) evaluated a goal-setting linked to incentives strategy for enhancing and sustaining healthy eating and exercise behaviour change in overweight and obese children. The cRCT was set within the context of ‘Go4Fun’; an existing Australian evidence-based community weight-management program [33]. The study was approved by the South West Sydney Human Ethics Committee (HREC/14/LPOOL/480), and site-specific approvals were obtained from research governance offices in participating local health districts.

Participants and Recruitment

A total of 18 parents (n=24 children) took part in 14 family

interviews and 1 group parent-only interview. The mean age of

participants’ children was 10 (±2) years, 16/24 were female

and the mean BMIz score of the children was 2.0kg/m2 (±0.46).

12/24 children spoke English as their primary language at home,

and 4/24 were from solo parent households. Participants were

selected from families already participating in the cRCT (treatment

and control) who consented to further research participation.

Children were aged 7-13yrs at the time of recruitment, had

a body mass index greater than the 85th percentile for their

age and gender [34] and met the criteria to participate in the

community weight-management program at participating sites

[32]. Informed written consent was obtained from all study

participants’ parents/ carers, and all participants were unaware

which components of the weight management program were

part of the trial vs the standard program. Families were recruited

for qualitative research via a survey of all parents administered

at the six-month follow-up assessment of the cRCT. Participating

families consented to participate in either a focus group or

family interview, and maximum variation sampling was used to

select participants based on family and program characteristics;

high (≥ 60% of sessions) and low attendance (≥0% of sessions),

single child and multiple sibling families, small (

Data Sources

The dataset comprised family interviews conducted with individual parents, groups of parents or parents accompanied by their children who participated in the weight management program. All interviews took place between March and June 2017, followed a semi-structured approach aided by discussion guides to facilitate natural conversation, and lasted approximately 1.5 hours. Interviews were audio recorded and confidentiality was agreed with participants prior to the interview.

Analysis and Interpretation

An inductive thematic analysis anchored in a constructionist theoretical framework was carried out, using a 6-step guideline framework for thematic analysis [35]. This approach allowed for theoretical flexibility, given the aim was to explore participants’ described experiences of the community program, as well as the wider context of their lives on potential influences on healthy behaviour. The analysis therefore aimed to produce latent themes. Family interviews were transcribed verbatim by GE to familiarise and then sort the data into initial concepts. Each transcript was scanned, systematically coded and organised into themes by GE. A second researcher then independently coded the transcripts, undertaking a reflexive dialogue to check whether extracts confirmed or contradicted the identified themes. A constant comparison method was used, where codes and themes were collapsed and expanded until no new themes were found. Themes were defined and reviewed amongst the wider research group, and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Previous work details how intervention components were developed for the cRCT [36]. In brief, the research team identified behaviour change concepts which informed the design of a goalsetting process linked to an incentives and rewards scheme for goal completion. This scheme was supported by additional theorybased intervention components including; a visual handout to help families plan incremental goals towards a bigger health outcome, a goals contract to encourage commitment to goals, a group tracking chart to publicly track progress, and a post-program lottery prize incentive with text message prompts for six-months after the weight-management program. The Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy (BCTTv1) [37] provided a framework for describing what was delivered by each of the cRCT components, and helped to draw out active, non or less-active behaviour change techniques (BCTs) within the cRCT components [38].

Transcripts were scanned and coded specifically for extracts relating to the influence of each cRCT component. ‘Goal achievement’ and motivation towards goal achievement, as reported by participants, was used as a proxy for healthy eating and exercise behaviour on which to evaluate the ‘activeness’ of the identified BCTs. Inferential links were made between parents’ accounts of their engagement with the intervention components and the associated BCTs identified in those intervention components. A separate document was used with the cRCT components as headings to guide the process, Using the taxonomy enabled this evaluation to build on an increasingly accepted common language for recognising and specifying components of behavioural interventions that are effective in influencing obesityrelated behaviours (use of the taxonomy supports the CONSORT guidelines for the reporting of behaviour change interventions [39]. BCTTv1 online training was undertaken to maximise practical proficiency in recognising and coding BCTs according to the definitions used in the taxonomy.

Results and Discussion

Attitudinal Characteristics of Participating Families (Aim 1)

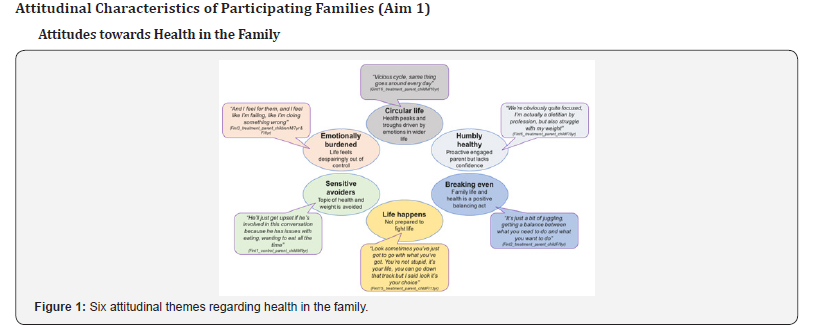

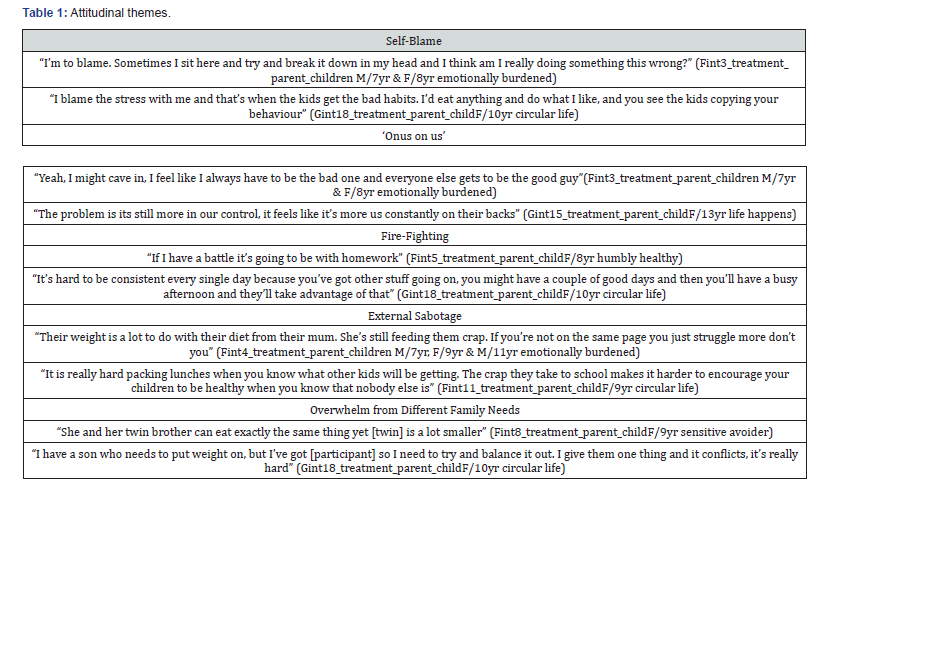

Six attitudinal themes regarding health in the family were found in participating families, which were used to describe the ‘types’ of families in the study (Figure 1). The emotional experience of the mother regarding caring for her family was central to these attitudes, particularly a lack of confidence and control and a sense of personal failure. Five further attitudinal themes were found (Table 1):

i. ‘self-blame’; guilt, failure or regret as a parent,

ii. ‘onus on us’; burden and resentment about shouldering responsibility,

iii. ‘fire-fighting’; stress due to lack of routine and hectic lifestyle

iv. ‘external sabotage’; victimization by external sabotage, and

v. ‘overwhelm from different family needs’; struggling with consistency and commitment.

These themes represented barriers to healthy eating and exercise in the family, whereas whole household involvement, choosing and building on activities the family was already doing, and having a routine at home were associated with goal completion in the program and facilitators of healthy behaviours. Previous literature has emphasised the importance of involving the whole family in weight management programs, including extending interventions to social networks which have been shown to have an influence on obesity patterns [40]. Identifying and helping families manage situations where loss of balance and control occurs in the household may therefore help to facilitate healthier eating and exercise behaviours.

Attitudes towards Incentivizing and Rewarding children at Home

Four themes were found (Table 2)

i. ‘reward systems are unsustainable at home’; parents felt giving their children money for chores reaches a limit, and on-going reward systems are unrealistic in terms of effort and expense required,

ii. ‘material rewards (at home) did not align with values’; for example, in Nigeria praise and encouragement of children was described by one family as more acceptable than giving material rewards,

iii. ‘threats are more effective than rewards’; particularly in relation to older children, and

iv. ‘parents have ingrained habits around food rewards’; making norms and habits hard to break.

Parents acknowledged a need to ‘re-wire’ their own habits, learn how to give non-food rewards, and re-frame pleasant occasions associated with food. Educating parents about appropriate rewards is an important component to continue incorporating into future weight management programs., however this research did not suggest that reward systems will be adopted at home outside of weight management programs.

Factors Influencing Impacts of the Strategy over 18-months (Aim 2)

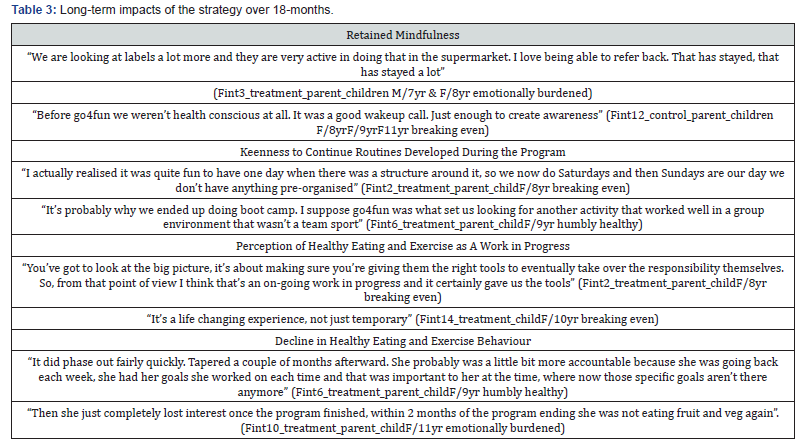

Four themes were identified that reflected the participants’ perceived long-term impacts of their participation in the community program;

i. ‘retained mindfulness’ (of healthy eating and exercise),

ii. ‘keenness to continue new routines’,

iii. ‘healthy eating and exercise as a work in progress’ and

iv. ‘a decline in healthy eating and exercise behaviour’ (Table 3).

Parents’ perceptions were mixed regarding direct attribution of long-term lifestyle changes to the weight-management program itself. Many parents said their children had ‘tapered off’ doing the specific goals set during the program and were no longer thinking in terms of ‘achieving goals’, within two-months of the end of the program (Table 3). However, several parents acknowledged their children had integrated learnings and life skills from the 10-week program into their daily awareness and described their attitude to health now as a ‘work in progress’ (Table 3). Some parents were inspired to continue with their weekly commitment to exercise after the program, encouraged by the new routines the goalsetting process had initiated (Table 3). Puberty was also identified by parents as an influential factor on health behaviours in older children, with the transition to high school referred to as a time of disruption and shifting of control over health-related decisionmaking and external influences on their child’s health behaviours;

“We’ve had some big changes, [participant] is in high school now and his appetite has changed a lot. He has periods where he’s more conscious, but since he’s started high school it’s definitely gone downhill, and peer group pressure” (Gint16_treatment_parent_ childM/10yr circular life)

Psychological Theory (Aim 3)

Active Behaviour Change Techniques

Table 4 summarises the behavioural theories underpinning the cRCT intervention components, and associated behaviour change techniques (BCTs). The most active BCTs in motivating goal completion during the ten-week program included; ‘goal-setting (behaviour)’ and ‘graded tasks’ via focusing on small incremental behavioural goals rather than outcomes, ‘action planning’ via recording implementation intentions, and ‘reviewing behaviour’ and ‘monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback’ via tracking goal progress.

Whilst ‘reward and threat’ was a core input to the cRCT, it was less motivating than BCTs based on ‘goals and planning’. This aligns with a theme found where parents described the rewards as an “added bonus” and more effective in encouraging attendance in the ten weekly sessions than goal completion.

“Setting the goals was an incentive but knowing there was going to be a reward was an added bonus. But that wasn’t the focus for her, we looked at the goal itself and that was what she was working on, not so much about the reward” (Fint8_treatment_ parent_childF/8yr)

“If there’s any sort of tangible reward at the end that’s a bonus for them. It was good but it wasn’t the reason why we kept coming back” (Fint6_treatment_parent_childF/9yr)

The interviews indicated that the incentives offered in the cRCT were overall accepted by parents despite their rejection of incentivising and rewarding children at home. This may support the idea that external reward systems (e.g. at school) are more likely to engage children than reward systems at home where the process of learning revolves around a child’s intrinsic motivation [41].

BCTs that were identified within the cRCT components, but less active in motivating goal-related behaviours included; ‘social comparison’ and ‘social reward’ (Table 4). Parents described their children as being more motivated by seeing their own progression than comparing themselves against others, and whilst ‘supportive praise’ was active via 6-month text message prompts, not all parents engaged with this component. The research team found a BCT that did not fit with BBTTv1 definitions but was inherent in the lottery prize draw cRCT component - ‘anticipation of future reward (non-certain)’. Family interviews indicated that anticipation of a larger but uncertain reward (i.e. lottery prize draw) was less active in encouraging behaviour change than anticipation of the frequent weekly incentives and rewards linked directly to goal achievement.

Links with psychological Theory

A combination of Self-Determination Theory [51] and Social Cognitive Theory [52] could explain the behaviours associated with the cRCT over ten-weeks and 18-months. Self-Determination theory based on Cognitive Evaluation Theory [53] and Organismic Integration Theory [54] describes how extrinsic motivations such as material incentives and rewards can facilitate intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation can be fostered if an activity (e.g. goal-setting) generates a sense of autonomy (choosing to conduct actions that align with own beliefs), competence (self-efficacy or perception of personal achievement) and relatedness (anticipated social interaction or social support) [55]. In the cRCT, parents and children agreed and wrote down the children’s goals together via a goals contract helping to satisfy perceived autonomy. Families were provided with weekly tracking and positive feedback on progress via a group tracking chart, and rewards for goal achievement which together helped to satisfy ‘competence’ (specifically, via creating a sense of progression), and weekly ‘check-ins’ with program leaders to evaluate goal progress helped to satisfy ‘relatedness’ (specifically, via perceived social support).

Accountability has emerged in a recent review of health-related psychological literature as a key mediator of the psychological factors necessary for supporting intrinsic (autonomous) motivation and longer-term behaviour change [56]. This theory has strong relevance to this evaluation. Although accountability is classically associated with extrinsic and ‘controlled’ behaviour, the sense of accountability generated by planning, agreeing and tracking of goals in the ten-week program, was identified by a previous work as key to intervention engagement, and intrinsic motivation [57]. A meta-analysis of three studies (on adults in a professional environment) found ‘autonomous motivation’ is closely related to goal progress and is mediated by implementation planning [58]. This supports the continued use of implementation intentions as part of goal-setting in future weight-management programs.

Families described their motivation to continue healthy eating and exercise as declining after the ten-week program (Tables 3 & 4), which coincided with a reduced sense of autonomy, progression and support. Post-program text message prompts were described as ‘pushy’ (lack of autonomy) and heightened parents’ perceived ‘onus on us’ (lack of support). There was also no visual or personalised feedback on progress after the ten-week program (lack of progress). These combined factors may explain why families no longer felt accountable to their goals and gave up. Many parents reported positive changes in their children at 18-months, including retained awareness of healthy eating and exercise. However, families found translating attitudes into behaviour after the ten-week program challenging, and future interventions may be enhanced by post-program initiatives that support psychological needs related to accountability rather than longer-term extrinsic incentive schemes (such as lottery-prize draws). There is evidence in the literature that ‘accountability partners’ help people keep a commitment through text [59]. The literature has also identified positive social feedback and praise as highly important in satisfying the need for self-efficacy and enhancing intrinsic motivation [56] which aligns with the parents who reported their children valued praise and recognition for their goal achievement over the material rewards.

Conclusion

This research demonstrated that parents can have different approaches and levels of confidence in managing healthy behaviour in their families but share similar emotional struggles that inhibit healthy eating and exercise in the family. This evaluation, combined with existing psychological literature, supports the concept of creating autonomous accountability around goal-setting as the focus of future weight management programs, which is potentially imperative to long-term behaviour change. Future interventions targeting health-related behaviour change should aim to avoid controlling approaches that detract from participants’ sense of control, self-efficacy and support. Program implementers should also strive to understand and work with participating families to manage inhibiting attitudes and barriers to the balance and control in their lifestyles.

This evaluation includes the provision of qualitative information providing context on influential family characteristics to inform the future design of family-focused health-related behavioural interventions targeting childhood obesity. The information also contributes to understanding the usefulness of behaviour change techniques within an established set of definitions, which will aid replication. Though this research represents views of parents rather than specifically the participating children it highlights the importance of understanding the family as a whole.

Acknowledgement

Author Contributions

GE led the drafting of all sections of the article in consultation with all the co-authors. GE moderated the interviews and led the analysis and interpretation of themes, with LC also independently coding the transcripts. JR and GE led the application for funding for this work. All authors provided substantial contribution to the concept and design of the evaluation, drafting the protocol paper and reviewing critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version for publication. GE, AG, MA-F, CR CIH, SL and JR also provided substantial contribution to the design and implementation of the associated cRCT.

Additional Acknowledgement

This evaluation would not have been possible without the contributions of the cRCT investigator team and Working Group. We thank all families and site leaders for their support and work on this study. We also thank Mr Simon Raadsma for his contributions and commitment to the project during his time at the Department of Premier and Cabinet. Investigators and Working Group members who are not co-authors on this paper, and their affiliates are listed below:

i. Office of Preventive Health: Anita Cowlishaw; Santosh Kanal; Nicholas Petrunoff

ii. Behavioural Insights Unit, Department of Premier and Cabinet: Shirley Dang

iii. Western Sydney LHD: Christine Newman; Michelle Nolan; Deborah Benson, Kirsti Cunningham

iv. South Western Sydney LHD: Mandy Williams; Leah Choi; Kate Jesus; Stephanie Baker

v. South Eastern Sydney LHD: Myna Hua; Linda Trotter; Lisa Franco

vi. North Sydney LHD: Paul Klarenaar; Jonothan Noyes; Sakara Branson

vii. Hunter New England LHD: Karen Gillham; Dr John Wiggers; Silvia Ruano-McLerie

viii. Mid North Coast LHD: Ros Tockley; Margo Johnson

ix. Better Health Company; Madeline Freeman; Bec Thorp

x. The George Institute for Global Health; Sarah Eriksson; Caroline Wu

In addition, we thank the Go4Fun program leaders, and representatives from our funding partner organisations, including the Heart Foundation, who have contributed to the development and implementation of the RCT.

Funding

This research is funded in-kind provided by the George Institute for Global Health, NSW Department for Premier and Cabinet and NSW Office of Preventive Health. GE is funded by an NHMRC postgraduate scholarship ID133318. At the time this research was conducted, JR was funded by a Career Development and Future Leader Fellowship co-funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council and the National Heart Foundation. AR is funded by an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship APP1124780. JR and AR are investigators on NHMRC program grant ID1052555.

Conflicts of Interest

SL is employed by the Better Health Company who are supported by the NSW Government to deliver the Go4Fun program. CR is the director, and CI-H is also employed by the NSW Office of Preventive Health, who manage the Go4Fun program.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (5th edn.), American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries 63: 1-21.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (2018) National Institutes of Mental Health, United States.

- van Steensel FJA, van Bögels SM, Perrin S (2011) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A metaanalysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(3): 302–317.

- Mehtar M, Mukaddes NM (2011) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in individuals with diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 5: 539-546.

- De Bruin EI, Ferdinand RF, Meester S, de Nij PFA, Verheij F (2007) High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in PDD-NOS. J Autism Dev Disord 37(5): 877-886.

- Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, Lewin AB, Arnold EB, et al. (2013) The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Develop Disord 43(10): 2450-2459.

- Dell’Osso L, Dalle Luche R, Carmassi C (2015) A new perspective in post-traumatic stress disorder: Which role for unrecognized autism spectrum. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 17(2): 436-438.

- Nietlisbach G, Maercker A (2009) Social cognition and interpersonal impairments in trauma survivors with PTSD. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma 18(4): 382-402.

- Kerns CM, Newschaffer CJ, Berkowitz SJ (2015) Traumatic childhood events and autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 45(11): 3475-3486.

- Stavropoulos K, Bolourian Y, Blacher J (2018) Differential Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Two Clinical Cases. J Clin Med 7(4).

- Trelles Thorne Mdel P, Khinda N, Coffey BJ (2015) Posttraumatic stress disorder in a child with autism spectrum disorder: Challenges in management. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25(6): 514-517.

- Morries LD, Cassano P, Henderson TA (2015) Treatments for traumatic brain injury with emphasis on transcranial near-infrared laser phototherapy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11: 2159-2175.

- Hamblin MR (2016) Shining light on the head: Photo biomodulation for brain disorders. BBA Clin 6: 113-124.