Social Avatar Theory: From In Vitro to In Vivo (Instagrammer Cognition - Mind the Gap)

David Brunskill*

Honorary Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Submission: April 02, 2019; Published: June 22, 2019

*Corresponding author: David Brunskill, Honorary Senior Lecturer, Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Auckland, New Zealand

How to cite this article:David Brunskill. Social Avatar Theory: From In Vitro to In Vivo (Instagrammer Cognition - Mind the Gap). Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 11(3): 555812. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.11.555812.

Abstract

The concept of a social avatar was proposed in 2013, in response to observed patterns of human behaviour on social media. Social avatar theory has since developed to provide a framework which can assist in the necessary task of being able to examine the potential effects of social media use upon user psyche. Through ubiquitous use of social media, social avatar theory has effectively moved from in vitro, to in vivo, and can now be applied in non-hypothetical terms. Via de-construction of publically available social avatar material, several aspects of social avatar theory manifest, with examples which illustrate the principles of curation, positive skew and gap/facade. In the process of de-construction, prototypical cognitive schema can be recognised (Instagrammer Cognition).

It is of concern that the mooted potential for psychological costs to be incurred, has also moved from hypothetical to real life (e.g. via a decrease in personal authenticity). Social avatar theory holds that a psychologically significant gap can develop between the online facade and the reality of life offline, and in doing so, that social avatars can be inherently psychoactive. For select users (further research required with respect to vulnerability factors), the creation/maintenance of a social avatar can become all-consuming, and even contribute to states of emotional distress and discord such as envy, smiling depression, or when the gap has grown so big as to be untenable, even risk psychological breakdown. As such, a social avatar health-check should be part of digital citizenship/education initiatives – Mind the Gap.

Keywords: Social Avatar Theory; Instagrammer Cognition; Digital Façade; Cyberpsychology; Mind the Gap

Introduction

Social Avatar Theory

““No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself, and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be true” [1].

The Scarlett Letter suggests two important things: Firstly, the need to create, utilise and maintain a façade, is part of the human condition. Secondly, this facade has been known to exert a psychological cost for centuries. What is novel, however, is the opportunity and extent that social media platforms and online social networks offer its users to groom, discern and polish the online aspects of their personal image into a curated presentation to others (as a digital, or online facade). This process is facilitated and delivered by the creation and maintenance of a social avatar [2].

The existence of a ‘social’ avatar was proposed in 2013, as a response to characteristic human behaviour observed online, where, ‘by selecting and posting written/visual material, individuals can self-manage image, and effectively create a social avatar’ [3]. A further examination of this process, noted that the representational material chosen, was likely to be positively skewed as per evolutionary forces (the ‘Sunday Best Phenomenon’), and that the process was cumulative, socially derived/driven, and resulted in a composite online image, or social avatar [2].

It was hypothesised that the effects of the social avatar could include the development of an online façade, and could facilitate the creation of a psychologically significant gap between online and offline aspects of the self - leading to the question being posed: Is Facebook good for us? [2]. Via clinical observation and anecdotal report, it was speculated that there may even be psychological consequences with respect to social avatar usage, and a latent potential to create psychological casualties [2]. Re-visiting social avatar theory in the context of global social media use and relevant publically available examples of social avatar material is therefore necessary and timely, and in addressing the vexed question as to whether social media is good/bad for us, may even prove to be of public health importance.

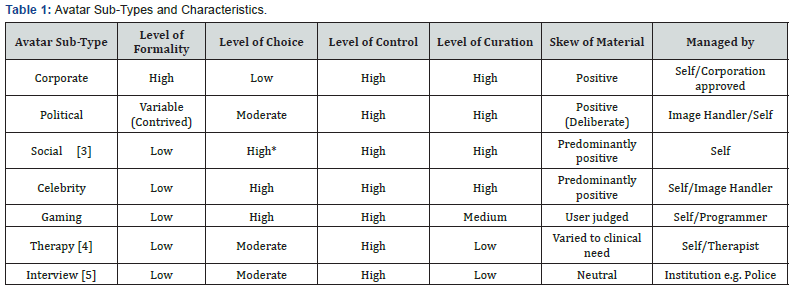

As the digital world has expanded, multiple avatar subtypes have emerged, each with different, but related characteristics, dependent on avatar purpose such as therapeutic agent [4], and interview facilitation [5]. Of these, the social avatar is considered to be relatively informal, with high levels of user choice and control, a high degree of curation, and a predominantly positive skew (Table 1).

*Level of (conscious) choice may be debatable due to internal and external psychological pressures

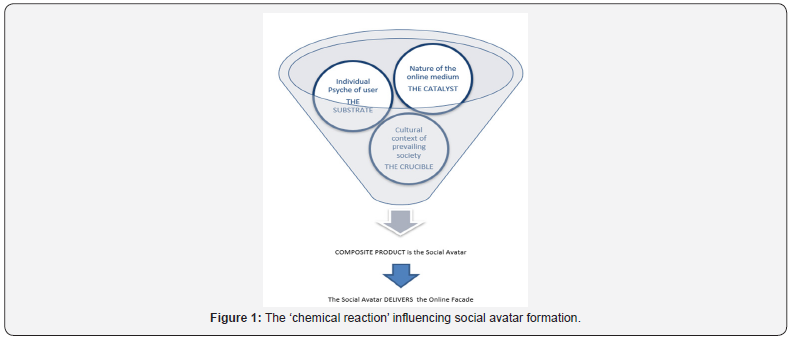

Social avatar theory is conceptualised as a synthesis of various inter-playing factors, including:

i. The enduring qualities of human nature (the tendency to present oneself in the best possible light [2] and the individual psyche, or e-personality of the user [6]).

ii. The nature of the online medium itself (immersive, disinhibiting, and addictive via reinforcement loops)

iii. The influence of the prevailing society (shifting contextual factors).

With respect to the online medium itself, a couple of realisations are fundamental: Firstly, the origins of social network development were ‘intrinsically concerned with image as a property from their very conception’ [7]. Secondly, and also from the outset, there was a ‘deliberate exploitation of vulnerability in human psychology’ [8], with insiders subsequently blowing the whistle on a cynical aspect of development:

“In asking, how do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible, a social-validation feedback loop was created. The ‘like’ button even gave users a little dopamine hit” [9].

Thirdly, the situation is dynamic, and as the prevailing forces of society shift, the norms/values and sanctioned/promoted aspirations, can coalesce anew. Thus, according to social avatar theory, characteristic behaviour online is driven by a complex interplay between related factors, somewhat like a chemical reaction (Figure 1).

Social Avatar Theory and the Psyche

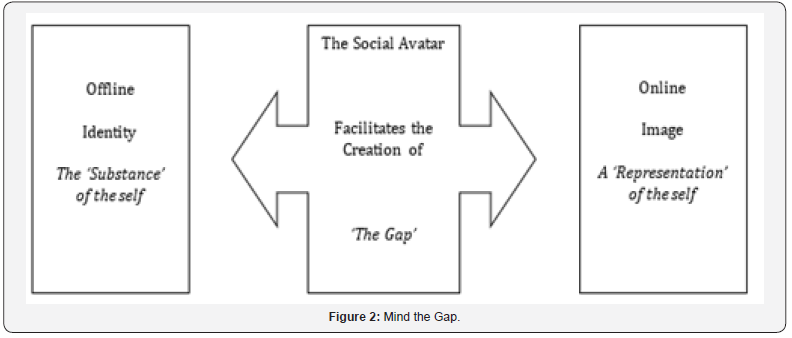

These digital times are unprecedented, largely unplanned, and have been described as equating to ‘a grand experiment with the psyche’ [6]. In terms of the relationship between social media and mental health, social avatar theory has proposed that a ‘by-product’ effect (of social avatar creation) is the potential for a psychologically significant gap to open up between the hoped for/idealised online self, and its less glamourous and more real offline manifestation [2] (Figure 2). This concern led to speculation that there could be psychological consequences for users, as ‘image is prized over identity, and representation over substance’ [2]. Social avatar theory effectively states that the process of social avatar formation has inherent psychoactive potential. The relationships at play though, are complicated, and some may even be bi-directional e.g. user self-esteem can be affected and influenced, in either a positive, or a negative, direction.

Due to this inherent psychoactive potential, social avatar theory has led to the concern that social media use may even represent a potential danger to user psyche, with various concerns, including perceived losses, such as to privacy, and authenticity [7]. With respect to psychological authenticity, it is contested that because human nature is dualistic i.e. individuals possess both good and bad qualities and this acknowledgement can assist in the maintenance of a positive sense of psychological well-being, that social media does not appear designed to promote, or enhance psychological authenticity [10]. Indeed, negative material being chosen to represent the self, has been described as highly unlikely to see the monitor, with positive skew playing a part in the modern jigsaw of rising narcissism [7].

Similarly, the development of unhelpful emotional states [2] (depression, anxiety, envy etc.), and the potential for psychological costs to be incurred (e.g. via the psychic energy required to maintain a flawless persona and when threatened, the need to save face [2], or face a rude awakening [6]), is also within the terrain of social avatar theory. Social avatar theory may also have indirect applications, such as in the bid to understand new manifestations of old human behaviours – ‘cyber’ bullying, for example, whereby the bully may take exception to an individual persona either off, or on line (via their social avatar material) and use technology to denigrate, or jockey for position, most likely in order to shore up their own insecurities.

Materials and Methods

Social Avatar Theory in Action and Objective

The objective of this study is to examine whether there is evidence to suggest that social avatar theory has a real life application. It aims to review publically available material, in order to identify examples where there has been a direct and clear relationship between social media use and user mental health. If located, social avatar theory will then be applied to selected examples to facilitate in-depth psychological analysis and interpretation of the material.

Five years on from the observation that a ‘social’ sub-type of avatar could emerge with significant psychological consequences, does evidence exist of the theorised characteristics in situ? For the theory to have validity/utility, then given the ubiquitous usage of social media, it was considered that it would be necessary to prove that the trajectory of concern had moved from the hypothetical to the realised (from in vitro to in vivo).

Social media usage has become ubiquitous, and the process of posting/sharing life aspects has become normalised and to a large degree, there is an expectation of participation, however mindless. Examples of the online space being harnessed by individuals seeking to create both a social avatar and a digital façade are therefore readily found in the public domain, in particular when the individual concerned has a deliberate stake in the process of social avatar construction, and may even be seeking to ‘trade in’ aspects of their identity, as a type of commercial enterprise.

In this regard, the realms of politics and celebrity – both of which harness social media in a deliberate (curated) and explicitly public way (Table 1) – were considered as potential sources for exemplar social avatar material, which could be analysed and dissected with a social avatar theory focus. Having screened for their illustrative potential, examples were chosen for analysis. Being a relatively new area of research, established methods or measures were not available, so the principle of making multiple analytical ‘rounds’ of the material [11] was utilised. As the materials studied are publically available and ‘stored’ online, the individual references contain exposure to the social avatar material itself, some of which is presented below.

Results

Political Exemplar

DDuring key times, Tony Abbott (former Australian Premier), maintained a Facebook page which uploaded an unusually large volume of imagery. A content analysis identified five main themes (military, heterosexual family, statesmanship, athleticism, activeness [12]). These relatively narrow themes, demonstrate the curation which can lie at the heart of social avatar construction and the central role a social avatar can play in the development of an online persona or facade – in this case, one which deliberately emphasised aspects with perceived political currency, as an attempt to project an image of the ‘Ideal Candidate’ [12].

Celebrity Exemplar

The political example above, confirms the social avatar theory of curation and positive skew. To further examine the effects of social avatar theory on an individual psychological basis, it is informative to consider the most prolific of individual users, some of whom can be found within the world of the internet celebrity, or the social media famous. Such users can probably be thought of as on a different sort of campaign trail i.e. for ‘likes’ instead of votes

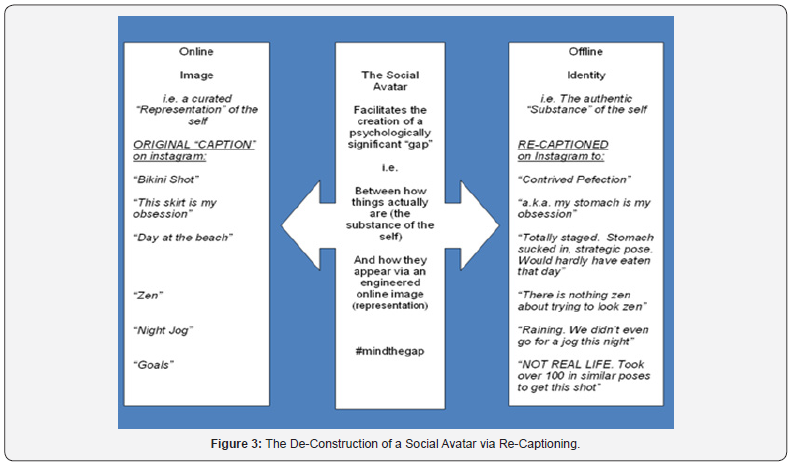

Essena O’Neill (EON) is a former Instagram Model. In late 2015, at the age of 18, she had accrued over half a million ‘followers’ on Instagram, when she experienced an emotional breakdown witnessed in the online public space, and most likely the private one too. In the period of turmoil, the lid was effectively blown off a tightly constructed and highly successful social avatar, in a way only an invested insider can. By exposing the painstaking process behind the construction and maintenance of her social avatar and online façade [13], EON delivered onlookers the first public dissection of a social avatar, and via the act of re-captioning her personal Instagram posts (Figure 3), effectively laid the social media platform of Instagram bare. In her attempt to salvage her sense of identity and re-boot her personal authenticity, EON effectively proved social avatar theory..

Discussion

Mind the Gap

IIn the days which followed the EON testimony, a series of honest captions began to emerge and trend as handles, including: #socialmediaisnotreallife, #thetruthbehind, #contrivedcelebrity, #celebrityconstruct, #nomakeup. It was even considered that this moment could assist others, like ‘13-year-old girls scrolling through photographs on their phones and wincing at the gap between perfect and real’ [14]. Briefly then, an online façade and celebrity persona had cracked, and a window into offline reality, warped wide open. Not all users enjoyed this moment of transparency though, and some (likely invested) users, appeared angry, defensive, and hasty to close it down, perhaps unable to recognise any aspect of their own self in EON’s admission of flaws.

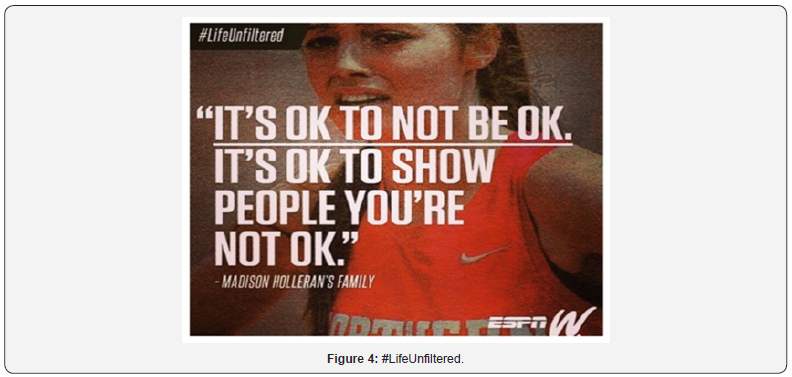

Thus, the EON testimony created polarisation, with expressions of both support: “it takes a lot of courage to tear down an illusionary identity” [15] and vitriol: “a dramatic self-de-throning” [16]. Yet, the matter was not psychologically trivial, and EON retrospectively disclosed suicidal thoughts at the height of her difficulties [15]. There are other examples, more tragic still, which have similarly demonstrated the potential seriousness of the situation, of when the gap becomes too wide (Figure 4) [17].

Seemingly, for some owners of a social avatar, the level of thought behind the curated representational material, is not accompanied by the same level of thought with respect to what the consequences of their social avatar may be upon their psyche. This is a situation which has not been helped by the platforms themselves, use of which comes without a health warning. Crucially, even individuals who do develop awareness (that their social avatar is a positively skewed curation which may be contributing to an online façade with unhealthy implications), may not necessarily extend this realisation to the social avatar material of others: “She (Madison) seemed acutely aware that the life she was curating online was distinctly different from the one she was actually living. Yet she could not apply that logic when she looked at the projected lives of others” [17].

The online façade created by social avatar theory, also has the potential to be implicated in states of depression, including the so called ‘smiling’ sub-type (whereby the internal experience does not match the external appearance, and antithetical, or mutually incompatible symptoms exist [18]). The gap facilitated by social avatar theory has also been noted to be fertile ground for smiling depression to thrive, as a void of realness gives more room for smiling depression to grow [19]. In this regard, a related, saddening and popular observation is the extent to which depression is said to have ‘no one face’ [20].

Instagrammer Cognition

In the light of clear examples of psychological harm, it is important to pause and consider what may be occurring on a deeper, cognitive level. Some online social networks (OSN) allow users to make ‘friends’, whilst others let users become, or accrue, ‘followers. Instagram is a ‘follower’ OSN, and one which is recognised to be both highly curated, and for some, of commercial value also. By designating follower status, Instagram has been criticised as ‘a one-way relationship, which without reciprocal exchange of information, can create the implication that the individual being followed is a ‘notch more important’ [21]. This is why the EON testimony and public dissection of her social avatar was a ground-breaking expose of this fallacy among many others.

Following the brave/treacherous (please delete one) act of re-captioning, EON used her platform to go further, stating: “Without realising, I’ve spent the majority of my teenage life being addicted to social media, social approval, social status and my physical appearance. Social media, especially how I used it, isn’t real. It’s a system based on social approval, likes, validation in views, success in followers. It’s perfectly orchestrated, selfabsorbed judgement” [13]. Later, she would reflect deeper still on her change of heart to conclude: “I felt so much shame over that façade (my perfectly edited life), that’s why I made the video…..I had become the very thing that deceived me as a young teen” [15].

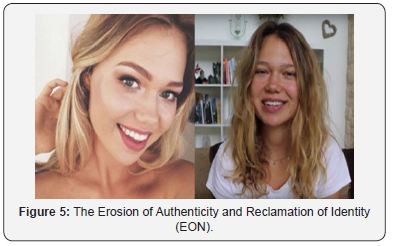

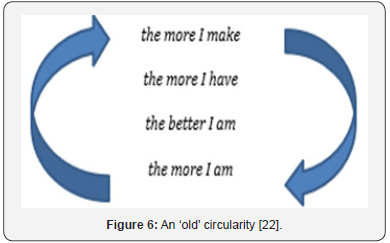

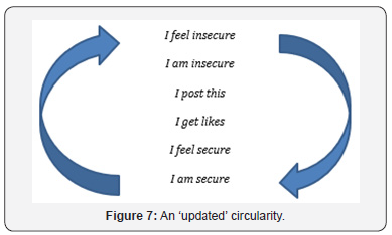

In broad psychological terms then, and according to social avatar theory, it appears likely that EON could no longer tolerate the gap her social avatar had facilitated between her offline real self, and her online persona. In the process and epiphany of her emotional breakdown, this gap was revealed for what it was, and for all to see, including making explicit the psychological toll that had come with the erosion of identity, the plunder of the self, and the drastic action it would take in order to begin her identity reclamation and eventual emotional recovery (Figure 5). Although nearly fifty years on from the work of the psychiatrist R. D. Laing, the cognitive schema which underpins this type of self-promotion - Instagrammer Cognition – appears eerily reminiscent of the binds and knots which Laing observed within the recurring patterns of human relationships [22]. It is as if an old circularity (Figure 6) has been updated (Figure 7).

In the case of EON, the complexity of the situation may actually be best understood in retrospect i.e. once honesty prevailed. It appears that the concept of deceit (of self, of others) via contrived perfection and flawless persona, was compounded by the social validation built into the OSN platform itself, and with the dynamic of followers, and the addition of ‘likes’ as a mechanism of validation, a positive feedback loop was set up, with clear addictive potential. In time, this would come to function as a personal and psychological trap, as the social avatar was fuelled to deliver ever greater gaps between online and offline realities. For EON, a social media influencer, this was probably further consolidated via financial, social and material gains. Where there were apparent psychological gains however, these proved fragile.

The Relationship between Social Media and Mental Health – a Double-Edged Sword

It has become apparent that social media has an intimate and bi-directional relationship with user mental health, and that a complicated relationship exists between the two. The example of EON testimony and social avatar dissection via recaptioning, provides categorical evidence that social media use has the potential to affect the psyche should it still be needed, and furthermore, confirms social avatar theory as a key concept in understanding and recognising the forces at play. In the interests of balance however, it is duly noted that although the EON example is clearly one of a negative, unhealthy relationship (between social media and mental health), there are other users who anecdotally report that social media can be a more positive force, for example by providing an opportunity to practice “learning to see ourselves in a more positive light” [23]. Research into depression in adolescents confirms this complexity and bi-directionality, with the same research team simultaneously finding that Instagram use clearly contributed to adolescent depression, but also had the potential to stimulate closeness [24].

With particular respect to young people (see Table 2 for the possible inclusion of age of user into a proposed vulnerability model), social media use has become recognised as a live public health issue. 91% of 16-24 year olds use the internet for social media, and for young people in particular, social media is recognised to have the potential for both positive and negative effects [25]. Indeed, literature review concludes likewise for all ages, noting that with respect to mental health, social media has both advantages and disadvantages [26]. Whilst the exact counter-balance of positives and negatives is unknown, for any given individual social media user, there can only really be three states:

i. The positives outweigh the negatives

ii. The negatives outweigh the positives

iii. The positives equal the negatives

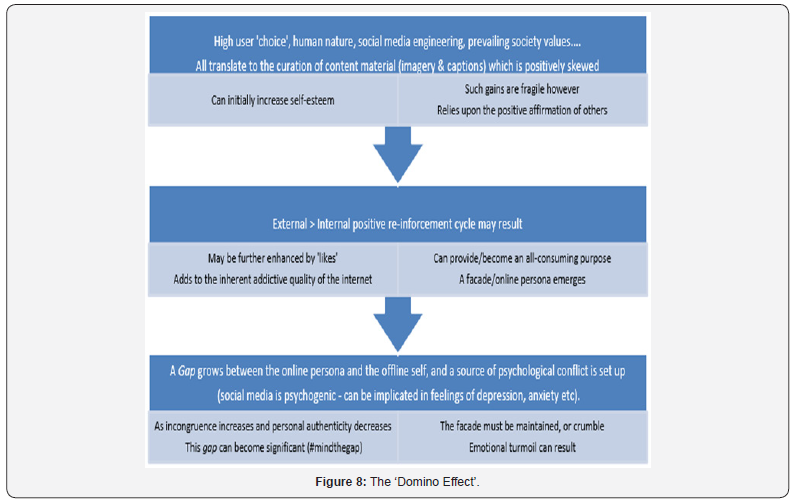

Social avatar theory can inform how this balance is arrived at for a given individual. For example, with respect to scenario ii - whereby the negatives outweigh the positives - the process appears to be a type of ‘domino effect’, whereby the cognition of the individual can undergo a gradual transformation (Figure 8).

Conclusion

Closing the Gap and Further Research

The answer to the question: ‘Is Facebook good for us? [2] can now be articulated thus: The use of social media is a double-edged sword for mental health (Figure 9).

With respect to user mental health then, it can now be stated with clarity and certainty that social media use has the potential to be ‘good for us/bad for us’. Beyond this conclusion though, lie both user needs and further (research) questions, or what has been termed, prevention and intervention [24].

For example, the need:

i. To provide education about the reality of the complicated, bi-directional relationship that exists between social media and the psyche

ii. To provide intervention when required – and in what form?

And the questions:

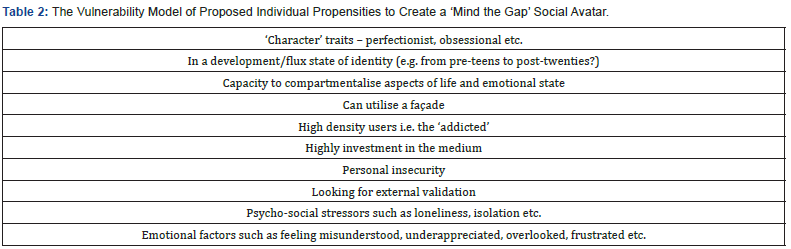

iii. What makes an individual likely to run into difficulties? (Table 2)

iv. What constitutes healthy use?

The internet interfaces with user mental health in many different ways and directions. Social avatar theory has been proven to exist in real, psychoactive, terms and can provide a way into understanding a complex situation.

For example, having established that for some individuals, social avatar theory can equate to a psychologically significant and potentially harmful gap, the next step will be to work out how to keep the gap manageable (prevention), and in some cases, to close it (intervention). Given the number of global users, social avatar theory should build on the individual concern, and look for an application on a population level. There is a clear need for a balanced viewpoint to develop with respect to social media and mental health, and the commentary of concern must take its rightful place at the table, alongside the promoted and purported benefits of social media use advocated by both individual users and the industry itself [23,27,28]. Social media platforms may have become a permanent and significant fixture of modern life, but their use needs to be subject to ongoing scrutiny, and where appropriate, come with relevant health warnings. Further research will be important in the bid to redress the balance and begin to understand what has been at stake in this grand experiment with the psyche [6].

The focus of concern needs to move beyond privacy and information issues, and start to encompass health-related concerns, including things which seem obvious (such as the addictive potential), as well as those which are more subtle and somewhat hidden (as exemplified by the call for social media platforms to highlight when photos of people have been digitally manipulated/air-brushed [25]). In this paper, many of the theorised characteristics of social avatars were found to have been realised, including the curation of a positive skew, incongruence between online image and offline identity (via digital façade), and the erosion of authenticity. For select users (see Table 2 for a vulnerability model), the creation and maintenance of a social avatar can become an all-consuming purpose, and possibly, via the creation of a psychologically significant gap, even risk significant emotional breakdown.

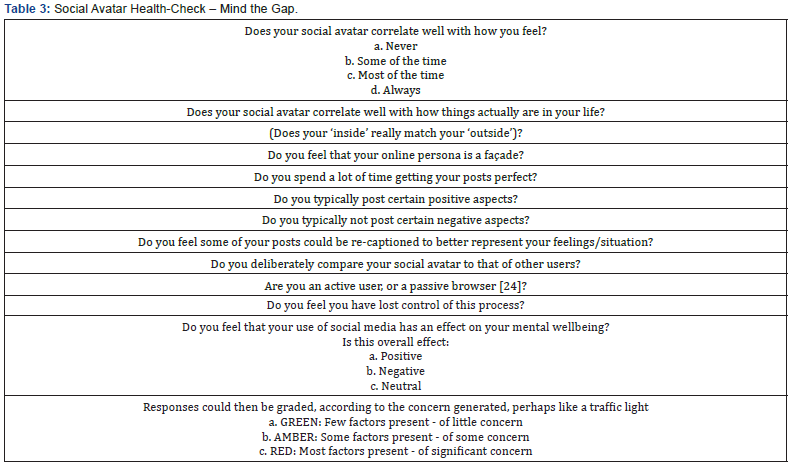

This paper contests that social avatar theory underpins much of the commentary of concern regarding the potential for social media use to become psychologically unhealthy. It is therefore proposed that with due reference to the sheer number of users, a social avatar health-check (Table 3) would be a welcome development, and one which could be integrated into digital education initiatives as part of health and wellbeing domains [29], and as part of digital citizenship teachings in schools [25], with the widened aim of assisting users to develop a psychologically balanced approach to their use of social media. In other words, a comprehensive digital education may allow young people to reap the benefits and adequately deal with the harms [30].

As clinical services start to respond to population need, and try to catch up to the breadth of the interface between the manifestations of the digital age and user mental health, the initial focus on gaming and other ‘internet addictions’ may also lead the way towards a comprehensive approach which necessarily includes the problematic or unhealthy use of social media. In this scenario, a social avatar health-check could be a useful tool in the process of assessment in the specialist clinic environment [31]. A social avatar health check may also be one of several useful departure points for further research into the daunting quest to define what characterises psychologically healthy use of the internet, and the development of robust psychological measures. It is already clear, that for as long as technological advance is allowed to outstrip emotional awareness, user psyche will continue to be exposed.

Conflict of Interest

No economic interest or conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to acknowledge the individuals behind the examples chosen to illustrate social avatar theory, and also to anyone who may have suffered exposure of the psyche via social media in the manner described, or similar.

References

- Hawthorne N (1850) The Scarlett Letter. In: Wordsworth Classics, US.

- Brunskill D (2013) Social media, social avatars and the psyche: is Facebook good for us? Australasian Psychiatry 21(6): 527-532.

- Brunskill D (2013) Social avatar – in 100 words. The British Journal of Psychiatry 203(5): 386.

- Craig, Rus-Calafell, Ward, et al. (2018) AVATAR therapy for auditory verbal hallucinations in people with psychosis: a single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 5(1): 31-40.

- Taylor DA, Dando CJ (2018) Eyewitness Memory in Face-to-Face and Immersive Avatar-to-Avatar Contexts. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 507.

- Aboujaoude E (2011) Virtually You – The Dangerous Powers of the E-Personality. In: 1st (Edn), W.W. Norton & Company, New York, US.

- Brunskill D (2014) The Dangers of Social Media for the Psyche. Journal of Current Issues in Media & Telecommunications 6(4): 391-415.

- Parker S (2018) As quoted in The Guardian Newspaper: Never get high on your own supply – why social media bosses don’t use social media.

- Parker S (2017) As quoted in The Guardian Newspaper: Ex-Facebook president Sean Parker: site made to exploit human ‘vulnerability’.

- Brunskill D (2015) Authenticity – in 100 words. The British Journal of Psychiatry 207(3): 242.

- Brunskill D (2017) Learning from the love letters of erotomania. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 28(5): 711-728.

- Hurcombe E (2016) The making of the captain: The production and projection of a political image on the Tony Abbott Facebook page Communication. Politics and Culture 49(1): 19-38.

- O’Neill, E (2015) Instagram Personal Content (posts) 27th October, 2015 onwards. This content was preserved, and featured in various places, including: 18-Year-Old Model Edits Her Instagram Posts To Reveal The Truth Behind The Photos. Former Instagram Model Edits Her Posts To Reveal Truth Behind The Photos.

- The Times (2018) Foges, C Naked models aren’t empowering anybody

- O’Neill E (2015) Essena O’Neill reveals the truth behind social influencer success in farewell treatise to online media.

- Speed B (2015) The lies of Instagram: how the cult of authenticity spun out of control NewStatesman Magazine.

- Fagan K (2015) Split Image, ESPN

- Christodoulou G (2012) Chapter: Depression as a consequence of the economic crisis. In: paper: Depression: A Global Crisis p. 14-18.

- Elmer J and Legg J (2018) Smiling Depression: What You Need to Know.

- Neje J (2018) 218+ Photos That Prove Depression Has No face.

- Hesketh J (2016) Influencers on Instagram: Insights Into The Fate Of Influencer Marketing

- Laing RD (1970) Knots. Tavistock Publications, London, UK.

- Elmore H (2016) Faking happiness on social media helped me cope with depression.

- Frison E, Eggermont S (2017) Browsing, Posting, and Liking on Instagram: The Reciprocal Relationships Between Different Types of Instagram Use and Adolescent’s Depressed Mood. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 20(10): 601-609.

- Status of Mind: social media and young people’s mental health (2017) Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), United Kingdom.

- Mattar M, Blatchford T, Alao A (2016) Facing the Truth about Social Media: Psychopathology among Social Media Users. Ann Psychiatry Ment Health 4(4): 1070.

- Geher G (2016) Instagram and the Development of Social Skills. Psychology Today

- Instagram (2017) Info Centre Post by CEO and co-founder.

- 10 Domains of Digital Citizenship Education (DCE). (2018) Council of Europe.

- (2019) #NewFilters: to manage the impact of social media on young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), United Kingdom.

- Marsh S, The Guardian (2018) NHS to launch first internet addiction clinic.