Aggressive Behaviour in Secondary Schools of Mesken Woreda: Types, Magnitude and Associated Factors

Tadele Fayso*

Researcher, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Submission: November 22, 2018; Published: March 11, 2019

*Corresponding author: Tadele Fayso, Researcher, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

How to cite this article:Tadele Fayso. Aggressive Behaviour in Secondary Schools of Mesken Woreda: Types, Magnitude and Associated Factors. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 10(5): 555800. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555800

Introduction

Manifestation of aggressive behavior is one of the major problems associated with adolescents in the secondary schools today. The pervading incidence of aggressive behavior among secondary school students is alarming. Eziyi & Odoemelam [1] revealed that aggressive behavior is “one of the most frustrating issues parents and teachers face, and that is normal in young children who do not yet understand that it is wrong and more importantly why it is wrong”. Obviously, some adolescents in the secondary schools exhibit one form of aggressive behavior or the other.

Though behavioral problems in schools take different forms; truancy, tardiness, insubordination, profanity; vandalism and aggression are worth to be mentioned. The causes for such behaviors are many in number. In addition to biological factors, the causes for misbehaving reside on parental rejection, poverty, viewing violence in the media, peers and gang influence and the frustration that accompanies low scholastic [2]. From the behavioral problems, aggression in schools needs special attention since it affects student’s proper development substantially in their schooling and later in life. Beck [3] indicates that children who are aggressive at early ages tend to show delinquent behavior during adulthood than those children who were not aggressive. In addition, students who were aggressive tend to score low in their academic achievement than those students who were not aggressive and tend to be poor in communication with their peer and teachers.

Although the word ‘aggression’ is both recognized and understood in the common usage of the term [4] it is used so broadly that it becomes virtually impossible to formulate a single and comprehensive definition. Despite the enormous literature on the topic, and the continuous effort shown by scholars dedicated to the scientific study of aggression, there is still considerable disagreement about its precise meaning and causes, with no singular or even preferred definition. Far from being a term describing a singular dimension, ‘aggression’ consists of several phenomena which may be similar in appearance but have separate genetic and neural control mechanisms, show diverse phenomenological manifestations, have different functions and antecedents, and are instigated by different external circumstances, Ramirez (1996,1998,2000). Further, an insufficient differentiation with other similar constructs, such as violence, antisocial behavior, or delinquency, makes the task of its definition even harder.

Aggressive behavior has been defined by experts in educational psychology in various ways. Wood et al. [5] defined it as “the intentional infliction of physical or psychological harm on others”. From this definition, it is obvious that for an act to be classified as an aggressive behavior, the infliction of physical or psychological harm on others must be intentional. Hence, unintended and accidental infliction of harm on others may not be rightly classified as aggressive behavior. Aggressive behavior among adolescents in secondary schools takes various forms. It can be physical or verbal. Physical aggression refers to inflicting injury on others, while verbal aggression entails using words that are intended to harm another person.

Aggressive behavior among adolescents in secondary schools sometimes takes the form of an over-reaction, screaming, shouting or becoming very agitated as a result of a very minor setback [1]. It also takes the form of quarrelling, insubordination, bullying, revolution, destruction of school property, protest, angry shouts of rebellion etc. It appears that students’ aggressive behavior stems from different factors. It can be traced to learners’ family backgrounds, community, school and value systems. If the learner is unstable due to the above factors, he/she may suddenly display deviant behavior, tends to be emotionally disturbed and exhibits destructive tendencies. Theories of aggression suggest that aggression is acquired through a process of trial and error, instructing, and observation of models. The aggressive behavior is affected by reinforcement, the past experiences of the person, the social environment or social milieu, and one’s personality [6].

Aggressions in schools revealed in different types and violence is one of the most prevalent and destructive behavior that adolescents face today, because they are risk of being either the victim or the committer of an act of violence, Marguire & Pastore (1998). In addition, early intervention with student who displays aggressive behavior is important because they are at substantial risk for future violent behavior delinquency and school withdrawal, Eron (1987), Kupersmidt & Coie, 1990). Scholars also identified some techniques that enable to minimize aggressive behaviors [7].

Though studies were made by Amogne Asfaw [8] which examined magnitude of disciplinary problem in Ethio-Japan Hidasse secondary school and another study made by Kinde Getachew & Mekonnen Sintayehu [9] which investigated types, magnitude, predictors and controlling mechanisms of aggression in secondary schools of Jimma zone. The present researcher strongly believes that more research needs to be conducted in the areas of behavioral problems as the problems are extensive, vary in nature and only little has been accomplished so far. On this premise, this study will attempt to investigate the types of aggression, its magnitude, predictors of aggression and methods that teachers use/ employ to control aggression in secondary schools of Meskan woreda of the Guraghe zone.

Context

The importance of developing positive interpersonal skills is considered essential to our society [10,11]. Prior studies examined the different forms of aggressions in schools. According to Bjorkvist et. al [12] these are physical, verbal and indirect aggression. Various factors were repeatedly mentioned in the literature as associated factors of aggression. These factors among others, were attributable to biological factors, socio demographic variables, parenting styles, personality and viewing violent films [2]. Scholars also identified some techniques that enable to minimize aggressive behaviors [7].

The current researcher has lived for more than ten years in Meskan woreda and during his stay in the woreda, it was very usual for him to hear about prominent aggressive behaviors like talking nasty words, teasing, threatening, disobeying school regulation, quarreling with and criticizing teachers among adolescent in secondary schools. However, there is no empirical evidence presented so far in the woreda to inform the school community about the types of aggression, magnitude, predictors and mechanisms teachers use to control aggression. This trend, as a social observation, is alarming and suggests the need for studies aimed at exploring the types of aggression, magnitude of aggression, predictors of aggression and methods that teachers practice controlling aggressions in secondary schools of Meskan woreda.

Purpose of the Study

The overall purpose of the study was to explore the types of aggression, magnitude of aggression, predictors of aggression and methods that teachers use to control aggressions in secondary schools of Meskan woreda. More specifically it is aimed at,

i. Indicating the types of aggressions that are commonly observed among adolescent in secondary schools of Meskan woreda

ii. Determining the magnitude of each type of aggression among adolescents in secondary schools of Meskan woreda

iii. Investigating the relative importance of some socio demographic variables such as sex, grade level, school setting and scores on perceived parenting (warmth/love and control/ demanding) as predictor of aggression among adolescents in secondary schools of Meskan woreda

iv. Exploring the mechanisms that teachers use to control aggression among adolescents in secondary schools of Meskan woreda.

Methodology

Since the objective of this study was to explore the types of, magnitude and predictors of aggression, as well as the methods that teachers use to control aggressions; the study involves different groups (teachers and students) and the nature of the research questions requires use of both quantitative as well as qualitative data with more weight to quantitative data and the data were collected and analyzed at the same time. For these reasons the study design was concurrent nested design and the qualitative data was nested to quantitative data.

Source of data were students, teachers and principals of Enseno and Koto secondary schools of Meskan woreda. The population of the study was 1875 students attending secondary education in six secondary schools of Meskan woreda of the Guraghe zone in 2014/15 academic year.

Meskan is one of the woredas in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region of Ethiopia. This woreda is named after the Meskan speaking Gurage people. Part of the Gurage Zone, Meskan is bordered on the south by the Silt’e Zone, on the west by Muhor Aklil, on the northwest by Kokir Gedebano, on the north by the Oromia Region, on the northeast by Sodo, and on the southeast by Mareko. Towns in Meskan include Enseno. Based on the 2007 Census conducted by the CSA, this woreda has a total population of 155,782, of whom 76,396 were men and 79,386 women; 11,388 or 7.31% of its population are urban dwellers. Most of the inhabitants were reported to be Muslim, with 60.19% of the population reporting that belief, while 34.55% practice Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, and 4.7% were Protestants [11]. Data received from Meskan woreda education office shows that the woreda had accommodated 1875 students (1256 or 67% male and 619 or 33% female) in six secondary schools in 2014/15 academic year. Among the students; 815 or 43.5 % were grade nine and 1060 or 56.5 were grade ten students.

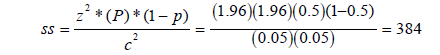

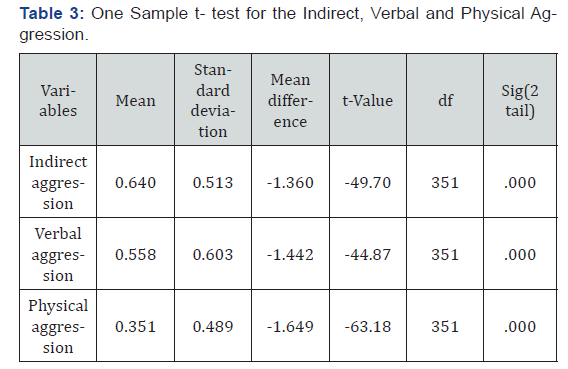

Since the target student population in the six secondary schools were 1875 (1256 male and 619 female); the sample size (SS) was determined considering 95% confidence level (α= 0.05), and prevalence (percentage of population) 50% and first using a formula for infinite Population (Godden, 2004).

And then adjusted to new Sample size (SS) for finite number of population (where the population is less than 50,000) using the formula derived from the first step.

Finally adding 10 % of 320 for design effect a sample size equals to 352 were considered for the study. Where, SS = Sample Size Z = Z-value (1.96 for a 95% confidence level), P=prevalence (Percentage of population expressed as decimal), C = Confidence interval (α), expressed as decimal.

In order to select the participants, multistage stratified random sampling method was used. As a result, Koto and Enseno secondary schools were selected from rural and urban schools respectively. At the second stage, grade level and sex were considered as other strata and all students of grade nine and ten of the selected schools were considered as a sampling frame for the study. The sample size (n=352) was selected with proportional weight to populations in each stratum (school setting, grade level and sex). The individual participant from each grade level and sex was selected using simple random method.

In addition, focus group discussion participants were randomly selected among school principals, vice principals and teachers who were engaged in teaching grades nine and ten and focused group discussions were conducted at each school regarding aggression controlling mechanisms that teachers use in their respective schools. The Direct and Indirect Aggression Scales [DIAS] [12] is a twenty-four-item instrument designed to measure three types of aggression: physical, verbal, and indirect.

There are seven items that measure physical aggression, five items related to verbal aggression, and twelve items regarding indirect aggression. The DIAS questionnaire is administered in groups (i.e., to each student in a class). Children and adolescents above ten years of age can complete the DIAS using paper and pencil, while younger children must be interviewed. The DIAS may be used in different forms (e.g., victim version and aggressor version) and for different purposes: for peer estimations, teacher estimations, and self-estimations. The aggressor version was used in the present study to measure aggressive behavior among adolescents in secondary schools of Meskan woreda. Items on the aggressor version of the instrument for the purposes of the present study include directions that instruct participants to answer how “you act when you have problems or get angry with each other”. Items include (1) Yell at or argue with the person I’m angry with, (2) Become friends with another person as a kind of revenge.

The original investigation of the DIAS was administered to 2,094 children ages eight, eleven, and fifteen in Turkey, Finland, Poland, Rome, and Chicago. Reliability for the subscales was reported in terms of internal consistency ranging from 0.78 to 0.96 Björkqvist [12]. Validity has been established in multiple studies [13-17] that used the DIAS to examine overt and relational aggression in children and adolescents, as well as correlating the subscale and total scores with the self, peer, and teacher ratings.

An investigation conducted by Pakaslahti and Keltikangas- Jarvinen [16] examined the relationships between peer nomination, teacher ratings, and self-report of direct and indirect aggression using the DIAS. Pakaslahti and Keltikangas-Jarvinen [16] report that the correlation (Pearson’s) between the scales was 0.58 (p < 0.001) for peer nominations of direct and indirect aggression, while reliability for the direct aggression scale was Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.76. The teacher rating of aggressive behavior reports that the correlation (Pearson’s r) between the direct and indirect aggression scales was 0.57 (p < 0.001), while reliability for direct aggression scale was Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.72. The self-rating portion of the study reported that the correlation (Pearson’s r) between the scales was 0.65 (p < 0.001), while the reliabilities reported were Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.81 and 0.70, for direct aggression and indirect aggression, respectively [16].

In order to measure parenting style 35 items which were adopted [18] from various sources, Dornbusch et.al., (1987); Baumrind & Black (1967) Becker, et al. (1962), Becker & Krug (1964); Schaefer (1965) was used. As indicated by the adopters ,the items on parenting styles required students to rate their parents in terms of the two dimensions of parenting styles, namely the warmth/love dimension and the control/ demandingness dimension. The warmth / love subscale consisted of eighteen items related to parental warmth, acceptance, and closeness to youngsters. This subscale measures the extent to which the student perceives his / her parents as loving, responsive, and warm.

The control/demandingness subscale consisted of seventeen items assessing parental monitoring and limit setting as well as parental pressure and encouragements toward high achievements. As reported by the adopters the items in the adopted scales were rated by two instructors from the Department of Educational psychology at Addis Ababa University regarding their appropriateness to the children and parents in the Ethiopian context the inter judge reliability index (Pearson r) was 0.93. Besides the items were administered to 152 students (Males = 76) from four towns (Ambo, Butajira, Debre Berhan & Harrar) of Ethiopia. The (Cronbach alpha) reliabilities were 0.91 and 0.89 for the warmth/ love and control/ demandingness dimensions respectively [18].

Focus group discussion(FGD) guide consists of eight items and developed by the researcher was used to collect relevant qualitative information from school principals and teachers regarding prevalence of aggression in general and controlling mechanisms of aggression in particular. The data collection instruments were piloted on 47 (25 male and 22 female) grade nine and ten students in Mekicho Secondary School. In order to ensure face/translation validity, forward and backward translation into Amharic (local language) and English were made by two independent language experts and wording clarity and consistency were checked together with the principal researcher. After collecting the data, the data were checked for consistency and errors double entered in Microsoft Excel Sheet and validated.

A clean database was generated, copied into SPSS (version 20.0) and all negatively worded items were reverted and then the whole data were computed using SPSS (version 20.0). Normality test was checked using histogram and found to be approximately normal. Internal consistency was cheeked using Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients and the Cronbach alpha reliability’s were 0.77 and 0.82 for direct and indirect aggression scales; whereas they were 0.71 and 0.89 for perceived warmth/love and control/ demandingness scales respectively.

The reliability index was compared with the previous finding of the developer for Direct aggression and indirect aggression (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.81 and 0.70); and adopters for perceived warmth/love and control/ demandingness (Cronbach alpha reliability’s 0.91 and 0.89) as mentioned above and the results were found to be quite similar.

Data Collection Procedures

The sources of primary data for the main study were all students and teachers selected from of Koto and Enseno secondary schools. After getting consent from woreda education office and the directors of Koto and Enseno secondary school; data for the main study were collected in three days (from 28 - 30 May 2015) and the questionnaire was administered to the participants in a specified room. Focus group discussion was one hour long and was conducted in each school with twelve and eight teachers of Koto and Enseno secondary schools respectively. The FGD was facilitated by the researcher and tape recorded.

Data Analysis Procedure

Frequency distribution of the study population according to school setting, grade level and sex were analyzed in order to understand the nature of the sampled data. Mean and standard deviation were computed to understand the prevalence of the three different types of aggression. Independent sample t-test was computed, and normality assumption was checked using histogram. Association of aggression scores with sex, grade level school setting and perceived parenting warmth/love and control/demanding were computed using Point-biserial and Pearson product-moment correlation. Only significantly associated variables were considered for further stepwise linear regression analysis. The data were first examined if they meet statistical assumptions of the model: normality, independence of errors, linearity, homoscedasticity and collinearity using histogram, Durbin–Watson test, scatter plotting, residual plotting and inter-correlation matrix respectively. All the assumptions were fulfilled.

The qualitative data collected through FGD were transcribed and data analysis was carried out using thematic analysis. The information was categorized using different themes as methods of aggression controlling mechanisms. Finally, based on the analysis, the major types of aggression controlling mechanisms practiced in secondary schools were identified and used to answer the fourth research question.

Findings

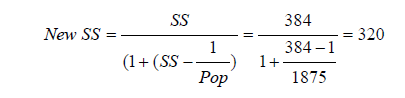

The results of the study were presented in three sections including the demographic characteristics of the sample, data analyses of each research question and a summary of the findings. (Table 1) above describes socio-demographic characteristics of the study respondents. The study respondents comprised 236 males (67.0 %) and 116 females (33.0%); Majority of the study population belonged to urban (257; 73%) and the rest belongs to rural (95; 27.0 %). Whereas (199; 56.5%) were grade ten and (153; 27.0%) were grade nine students.

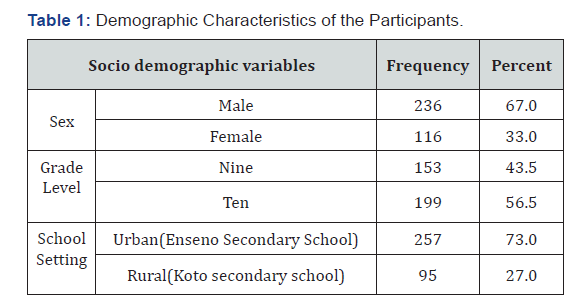

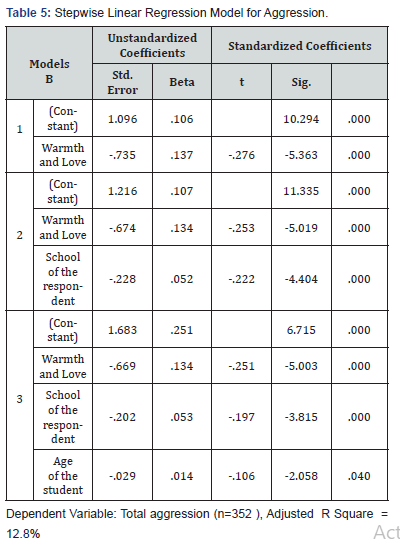

The data presented in Table 2 show that the three forms of aggression were observed in secondary students of Meskan woreda at different level. Indirect and verbal aggression was relatively the most prominent. Similarly, the teachers and principals in both Enseno and Koto schools have reported that the three types of aggressions are fairly observed among the students. To determine whether the observed magnitudes in each form of aggression was significantly different from the hypothesized population mean or not, a one sample t-test was employed. Table 3 above indicates that significant mean differences were observed between the hypothesized population means for each form of aggression and the sample mean of indirect aggression (M = 0.640, SD = 0.513), t(351) = -49.70 , p = .000, verbal aggression (M = 0.558, SD = 0.603), t(351) = -44.87, p = .000 and physical aggression (M =0.351, SD = 0.489), t(351) = -63.18 , p = .000. The third objective of the research was investigating the relative importance of some variables such as sex, age, grade level, school setting; perceived parenting warmth/love scores and control/demanding scores as predictor of aggression among adolescents in secondary schools of Meskan woreda. To meet this objective, linear regression analysis was conducted. First, correlation matrix was computed using point biserial correlation and Pearson product-moment correlation based on scale of measurement and then, only variables those significantly correlated with the independent variables fitted in to the model of stepwise linear regression analysis to test their prediction powers of aggression (Table 4).

The correlation coefficient among the dependent variable (aggression) and the independent variables sex (male coded 0, female coded 1), grade level (9th grade students coded 0, 10th grade students coded 1), school setting (Rural coded 0, urban coded 1) and scores on perceived parental warmth/love and control/demanding) scores reveled that school setting, age, grade level and scores on the measure of perceived parental warmth/love significantly negatively related with aggression. Subsequently, linear regression analysis was conducted to determine significant predictors of aggression taking only significantly correlated variables. As (Table 5) shows, the linear regression analysis reveals that only school setting, age and scores on the measure of perceived parental warmth/love found to be significant predicators of aggression. Together, the four independent variables have explained 12.8% of the variance in aggression (F (3, 348) = 18.123, P = .000). This indicates that the variability in aggression is only partly explained by the predictor variables.

Regarding Control mechanisms of aggression; the FGD participants in both Koto and Enseno schools have reported nearly similar control mechanisms. The responses are listed below in descending order of how often a certain method was used by the selected teachers and principals. Advising, handing over the wrong doer to discipline committee, consulting with parents, expelling from class and Suspending /dismissing from the school were reported in both schools.

Discussions

According to the findings of the study three forms of aggression namely indirect, verbal and physical were observed among adolescent in secondary school of Meskan woreda. Regarding the magnitude of aggression, the findings indicate that adolescent in secondary school of Meskan woreda scored relatively high on the measure of indirect aggression followed by verbal aggression and physical aggression. However, as the data shows the students reported low level of indirect, verbal and physical aggression as compared to the theorized population mean (i.e. 2.0) in each form of aggression. The FGD participants in both schools have also confirmed that all forms of aggregations are prevalent at different magnitudes. This finding is consistent with the findings of other researchers in in secondary schools of Jimma zone.

In the cross-sectional study that investigated the types of aggression, magnitude of aggression, predictors of aggression, and methods that teachers use to control aggressions in secondary schools of Jimma zone, et al. [9] found that physical aggression, verbal aggression, and indirect aggression were evident among adolescents in secondary schools of Jimma zone but with different magnitude. As the FGD participants in both schools (Koto and Enseno) disclosed “it is common to hear grade nine and ten students of the target schools talking nasty words, teasing, threatening, disobeying school regulation and criticizing teachers such forms of behaviors are communicable and could poison other students and will be intensified among the secondary schools of Meskan woreda”.

As cited by Kinde Getachew and Mekonnen Sintayehu [9] the other justification lies on the ability of grade nine and ten students to express aggression through indirect and verbal means as their recent stage is characterized by greater development in language usage and thinking ability. The developments in these areas could shift physical type of aggression to indirect and verbal aggression [19], explained when verbal skills develop, verbal means of aggression tend to replace physical ones whenever possible. For the indirect aggression, their justifications reside on the development of social skills. They noted that as social skills develop, even more sophisticated strategies of aggression are made possible, with the aggressor being able to harm a target without even being identified.

Based on the magnitude and sign (-) of correlation coefficient among the dependent variable (aggression) and the independent variables; the finding implies that 10th grade students displayed less aggressive behavior than 9th grade students whereas urban school (Enseno) students displayed more aggression than rural (Koto) school students and as the age of the student increases aggression decrease. Students who scored high on both measures of perceived parental warmth/love and control/demanding are manifesting low level of aggression. The linear regression analysis reveals that school setting, age, grade level and scores on the measure of perceived parental warmth/love found to be significant predicators of aggression

A large body of researchers relates perceived warmth /love parenting with children pro-social behavior. For instance, parents who are accepting, warmer, and helpful will have children that are less involved in antisocial behavior. Another research finding also state that family interaction patterns and parental discipline practices strongly affect the development of aggressive behavior in children [20]. In the other hand several researches have also shown the importance of sex in predicting physical aggression [21-30]. These findings have not supported the present study. The possible reasons will be the effect might be masked due to social desirability biases [31-40].

It was also found that teachers in the selected secondary schools have not practiced the proper way of handling aggressiveness. As they responded, they advise students and take some forms of disciplinary measures. It is not clear that what type of advice they offer to the aggressors and there were no well-established counseling and guidance mechanisms [41-45]. Current researches, however, have indicated some forms of effective techniques of handling aggression. As Grohol [7] indicated the most effective programs are those that help students to learn key social skills such as listening, thinking about the feelings of others, working cooperatively and being assertive in constructive ways. Grohol [7] also noted that most aggressive children are choosing to use that behavior because they don’t have the skills to achieve what they wish to achieve any other way [46-50].

Conclusion

Based on the summary of the findings indicated above, the researcher draws the following conclusions, and their corresponding implications:

i. The result of the current study showed that physical aggression, verbal aggression and indirect aggression were evident among adolescent in secondary schools of Meskan woreda. Specifically, students showed greater indirect aggression followed by verbal and physical ones, but all the three forms of aggression were found to be low [51-56].

ii. The findings also indicated that school setting, age, grade level and scores on the measure of perceived parental warmth/ love found to be significant predicators of aggression. On the other hand, sex and scores on the measure of perceived parental control/demanding did not predict aggression significantly.

iii. The result also revealed that the methods that teachers used to control aggression among adolescent in secondary schools of Meskan woreda. They mentioned various methods which includes both positive and negative reinforcements. Among others, advising was used by almost all teachers in conjunction with handing over the aggressor to discipline committee and taking the necessary measures in accordance with the regulation of the discipline committee. This implies that most teachers and principals practice positive reinforcement mechanisms more frequently to shape the behavior of the students [57-59].

Recommendations

This research explored the various types and magnitude of aggression that were prevalent among adolescents in secondary schools of Meskan woreda. It also pinpointed some of the variables those predict aggression and the methods that teachers practice controlling aggression. In the light of these findings, the following recommendations are forwarded.

i. Parents should be aware to be affectionate, accepting and helpful for their children and schools should have regular parent awareness programs based on their experiences and research.

ii. Teacher and principals should be aware about the correct way of handling aggressive behaviors and there should be consistent reinforcement mechanisms.

iii. Future researches should consider other variables like parental income, out of school engagements like viewing violent films, personality and the four typology of parenting styles to test in what way these variables predict the various types of aggressions

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (5th edn.), American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries 63: 1-21.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (2018) National Institutes of Mental Health, United States.

- van Steensel FJA, van Bögels SM, Perrin S (2011) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A metaanalysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(3): 302–317.

- Mehtar M, Mukaddes NM (2011) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in individuals with diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 5: 539-546.

- De Bruin EI, Ferdinand RF, Meester S, de Nij PFA, Verheij F (2007) High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in PDD-NOS. J Autism Dev Disord 37(5): 877-886.

- Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, Lewin AB, Arnold EB, et al. (2013) The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Develop Disord 43(10): 2450-2459.

- Dell’Osso L, Dalle Luche R, Carmassi C (2015) A new perspective in post-traumatic stress disorder: Which role for unrecognized autism spectrum. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 17(2): 436-438.

- Nietlisbach G, Maercker A (2009) Social cognition and interpersonal impairments in trauma survivors with PTSD. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma 18(4): 382-402.

- Kerns CM, Newschaffer CJ, Berkowitz SJ (2015) Traumatic childhood events and autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 45(11): 3475-3486.

- Stavropoulos K, Bolourian Y, Blacher J (2018) Differential Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Two Clinical Cases. J Clin Med 7(4).

- Trelles Thorne Mdel P, Khinda N, Coffey BJ (2015) Posttraumatic stress disorder in a child with autism spectrum disorder: Challenges in management. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25(6): 514-517.

- Morries LD, Cassano P, Henderson TA (2015) Treatments for traumatic brain injury with emphasis on transcranial near-infrared laser phototherapy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11: 2159-2175.

- Hamblin MR (2016) Shining light on the head: Photo biomodulation for brain disorders. BBA Clin 6: 113-124.