Reflections on the Therapeutic Alliance and Collaborative Care in Mental Health Nursing

Jan Sitvast*

Department of Health Care, Europe

Submission: January 28, 2019; Published: February 11, 2019

*Corresponding author: Jan Sitvast Ph.D, Lecturer, Department of Health Care, Hogeschool Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 7, Utrecht, 3584CS, Netherlands, Europe

How to cite this article:Jan Sitvast. Reflections on the Therapeutic Alliance and Collaborative Care in Mental Health Nursing. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 10(4): 555793. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555793

Abstract

This article is about the need in mental health nursing for a conceptual framework that can help nurses to bring about a therapeutic alliance with their patients and keep it up during the time patients are in their care. We mean a collaboration that involves active and conscious participation from both sides. The same question has been asked and been investigated for other health professions, for instance psychologists and psychotherapists [1,2]. In nursing the issue was raised only recently with the introduction of complex intervention programs as the Collaborative (Stepped) Care programs (CCP) and the Chronic Care Program [3]. Bordin [4] is often used to describe the therapeutic alliance. “The core of Bordin’s theory is that the alliance is a negotiated, collaborative feature of the treatment relationship, composed of three aspects” [5].

It is actually a working alliance. Bordin described it as having three elements:

1. An agreement on goals

2. An assignment of task or a series of tasks

3. The development of bonds

This threefold division relates the intentional domain (what is it that the patient wants?) with the cognitive and methodical (treatment-and support activities) and the affective element (e.g. does a patient feel that he is understood, respected and supported: does he have confidence in the expertise of the professional?). Let us see how this works out in mental health treatment care paths. We will use the Collaborative Care Model, that has been developed in somatic care for patients with chronic comorbidity but was also successfully transferred to mental health care for treatment of patients with depressions, anxiety disorders and borderline personality disorder [6-8].

We do so in order to demonstrate how Bordin’s three elements can be identified in the clinical care process. Collaborative Care Programs are set up to increase shared decision making and to enhance self-management skills of chronic patients. Collaborative relationships are realized when patients, their informal carers, and care providers develop shared goals and mutual understanding of roles, expectations and responsibilities. This will lead to more effective self-management and a better quality of life, when patient experience they can better cope with problems derived from their disorder [9,10]. Nurses play an important role here, but only when they master good clinical reasoning competences and can apply methodically sound interventions based on apt theoretical frameworks [7]. Therefore, this article purports to sketching an outline of necessary theoretical frameworks.

The Collaborative Care Model and Therapeutic Alliance

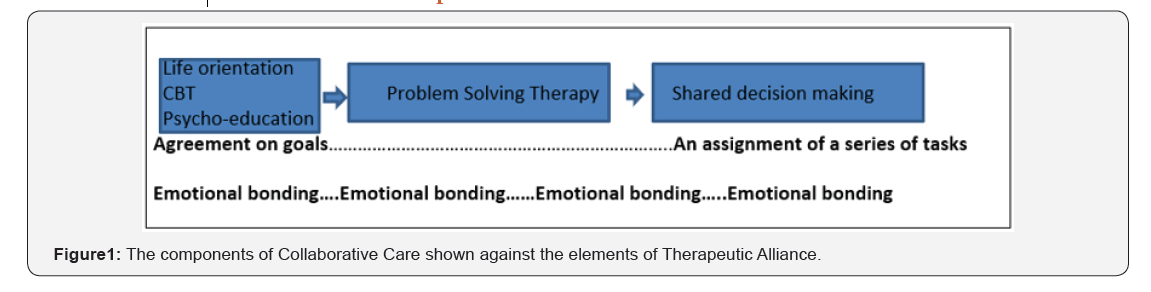

In the Collaborative Care Model there are the following components (Figure 1: blue boxes). We have compared them in terms of the three elements of Bordin.

The first component of the Collaborative Care Model and part of the second one aim at developing goal readiness, that is:

a) Being able to formulate goals based on things that you consider important in your life (values, strengths) and reflected on in what is called ‘Life Orientation’.

b) Knowing which actions are necessary to achieve a goal (pathfinding) that is discussed in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Psycho-education.

c) Finally, the patient’s awareness that you can do it, have the energy and concentration and that you have the necessary skills (agency). This goal readiness precedes the actual solving of problems and the process of shared decision making, as also problems are directly associated with values and goals in life and how to realize them.

We have not yet identified Bordin’s third element: development of bonds. Where can it be situated in the care process? Let us first examine how the development of bonds depends on the following factors:

1. Patient related factors, for instance: what does the patient expect from the professional? How is his perception of the professional?

2. Therapist related factors:

a) Personal attributes: flexibility, honesty, reliability, sincerity, warmth, etc.

b) Therapeutic techniques: exploration, reflection, being supportive, having attention for successes in the past, facilitating the expression of affect, being affirmative, giving room for the patient experience, etc.

The therapist related factors have been demonstrated to contribute positively to strong therapist alliances [1]. A better understanding into the mechanism how these factors act on goal formulation, problem solving, and shared decision making may make it possible for nurses to develop methods that would forge stronger therapeutic alliances which could ultimately result in better patient outcomes. Where can we position emotional bonding here? The values-based goal formulation, based on reflection and awareness of practical courses of action and what it takes in terms of skills, energy etc. must be brought out into the realm of explicit expression.

Otherwise it remains only an inner world ethereal thing. When it is been expressed in language and images then it invites sharing and calls for a response from others and feedback that vitalizes and enriches the reflection [11]. This is where the emotional bonding stands for that lifts the mere cerebral rational reflection and insight to the level of enactment, engrained in the emotions of life itself and thus creating a lived reality shared with others and commented on, therefore shaped also by the social environment. The identity of every human being, except for what is innate to us as unique individuals, is created by the multiple levels of how we are embedded in social contact. What is at stake is exactly the identity or rather the personhood or the quality or condition of being an individual person. This personhood is at danger by the chronic disease and its psychosocial consequences. So, on one hand we have this hermeneutic meaning making that is grounded in lived life and results in actions and (treatment) goals. On the other hand, we have the moral dimension of vulnerability and patients whose condition and health cannot be repaired (anyway not fully) by mere actions, goals and problem solving.

Patients then need not empowerment so much or that they are restored in taking direction over their lives, as failing direction is exactly what is part of life not only for patients but for every one of us. We cannot control everything. Bad luck happens. Chronic diseases will not go away. Often, we must make do with what comes our way. The process of emotional bonding in the professional-patient contact aims as much or even more at dignity than at goal readiness. The process of emotional bonding therefore runs as an undercurrent through the care process and therefore could not be associated exclusively with one of the components in the Collaborative Care Model.

What does this mean for the professional? To start with: an awareness and sensitivity when to promote goal readiness and when to focus on the upkeep of a person’s dignity. There is a demand for emotional intelligence in professionals to realize both sides of this hermeneutic-moral agenda and maintain a therapeutic (working-) alliance. Compassion, empathic feeling are conditions and qualities that nurses should use but they must be steered by the professional in a certain direction. In emotional intelligence the ‘intelligence’ aspect stands for knowing how to deploy them. What we need is a conceptual framework that gives direction to the intelligent deployment of therapeutic techniques that aims at emotional bonding.

The conceptual framework: a first Outline

The concepts that we propose are set in opposition of each other: place/space and gaze/face. How can you as a professional maintain a psychological space between you and the patient which is not taken over and dominated by the medical narrative (diagnoses, prognosis and treatment rationale) and professional jargon? How to create a place in which the patient can tell what it means to be ill and how it affects his life? A place where his voice (metaphorically) is heard. The more neutral space then becomes a certain place. Narrative and story-telling are the medium here. Something similar happens when the place where the patient resides and is treated is experienced as an arena, a stage upon which the patient is an acting agent instead of a place where one receives treatment passively.

It is all about being heard and being seen as a person. Then we have this other pair of opposed concepts: gaze/face. The clinical diagnostic look (gaze) should not pervade every contact of the professional with the patient but must be alternated with an open mind: perceiving the face of a person and seeing the person who she or he is instead of the patient with a certain diagnosis. It is necessary to recognize the vulnerability of the patient as essentially the same as ours. Then the perspective of the professional and that of the person in our care can meet each other in a dialogue that encompasses the reciprocity of being human souls facing the harshness of life. This is the true essence of emotional bonding and will affect the process of shared decision making

theoretical Framework1

How to combine the skills of emotional intelligence with the pragmatics of story-telling and the reflection on the meaning of one’s life, that is how to live a life that is redeemed as satisfactory and hopeful? Be aware: this does not necessarily mean (but at the same time does not exclude either) that pragmatic treatment goals are achieved. It does mean that dignity and integrity of someone’s personhood is restored or maintained. In other words that nurses contribute to the keeping of face and the prevention of losing face in interaction (which is not a small thing when you are perceived as ‘mentally ill’ by others). A patient must be in the opportunity to voice his perspective and his narrative be honoured by identifying where it reflects authentic values of the person.

The way that nurses can do this is by means of a narrative approach. Let’s see how this looks like:

a) Make the client’s narrative the starting point and find a common ground you (professional and client) can both relate to. Then try to develop this in a shared story line (see for an example: Sitvast [12].

b) Challenge the client to alternate a perspective or the role he or she takes in his own story and then see how this influences the story plot.

c) Make use of metaphors to suggest visual imagery for what otherwise would need a thousand words to explain or describe. See for an example Sitvast [13]

d) Simply inquire after what the problem is and in this way trigger reflection on the 5 components of the narrative pentad (agent/actorship, an action, a goal, a setting, and an instrument).

The Dutch psychiatrist [14] called this diagnostic of the questioning mode, which is versed in common everyday language.

1. What happened with you?

2. What is your vulnerability and what is your strength?

3. What would you like to achieve?

4. What do you need for this?

We will elaborate on these issues further and develop the hermeneutic-moral framework in another publication in which we will expand the concepts with others in order to build a model that will assist nurses in finding ways and interventions for true collaboration and dialogue with the patient.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (5th edn.), American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries 63: 1-21.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (2018) National Institutes of Mental Health, United States.

- van Steensel FJA, van Bögels SM, Perrin S (2011) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A metaanalysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(3): 302–317.

- Mehtar M, Mukaddes NM (2011) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in individuals with diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 5: 539-546.

- De Bruin EI, Ferdinand RF, Meester S, de Nij PFA, Verheij F (2007) High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in PDD-NOS. J Autism Dev Disord 37(5): 877-886.

- Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, Lewin AB, Arnold EB, et al. (2013) The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Develop Disord 43(10): 2450-2459.

- Dell’Osso L, Dalle Luche R, Carmassi C (2015) A new perspective in post-traumatic stress disorder: Which role for unrecognized autism spectrum. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 17(2): 436-438.

- Nietlisbach G, Maercker A (2009) Social cognition and interpersonal impairments in trauma survivors with PTSD. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma 18(4): 382-402.

- Kerns CM, Newschaffer CJ, Berkowitz SJ (2015) Traumatic childhood events and autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 45(11): 3475-3486.

- Stavropoulos K, Bolourian Y, Blacher J (2018) Differential Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Two Clinical Cases. J Clin Med 7(4).

- Trelles Thorne Mdel P, Khinda N, Coffey BJ (2015) Posttraumatic stress disorder in a child with autism spectrum disorder: Challenges in management. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25(6): 514-517.

- Morries LD, Cassano P, Henderson TA (2015) Treatments for traumatic brain injury with emphasis on transcranial near-infrared laser phototherapy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11: 2159-2175.

- Hamblin MR (2016) Shining light on the head: Photo biomodulation for brain disorders. BBA Clin 6: 113-124.