Tribalism and Clone Theory in New Leaders and the Resulting Degradation of Organizational Culture

Anton Shufutinsky1-4*

1 Changineering Global, USA

2 Cabrini University, USA

3Academy of Interdisciplinary Health Science Leaders, USA

4 NTL Institute for Applied Behavioral Science, USA

Submission: December 12, 2019; Published: January 09, 2019

*Corresponding author: Anton Shufutinsky, DHSc, MSPH, Changineering Global, Cabrini University, Academy of Interdisciplinary Health Science Leaders, NTL Institute for Applied Behavioral Science, USA.

How to cite this article: Anton Shufutinsky. Tribalism and Clone Theory in New Leaders and the Resulting Degradation of Organizational Culture. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 10(2): 555788. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555788.

Abstract

New leaders are vital to organizational continuity as people retire, leave for other opportunities, or become promoted. New leaders face numerous challenges, but when comprehensive leadership development programs are not implemented in organizations to aid them in their new roles, new leaders can face numerous obstacles to effective decision-making, managing, and leading effectually and successfully. This article discusses the interconnected nature of organizational leadership, culture, structure, and systems, among other elements, and how they can be affected by certain conditions and behaviors as well as how they affect organizational outcomes. This includes leadership behaviors, structures, cultures, and subcultures that pre-date the arrival or promotion of new leaders and create conditions for leadership ineffectiveness due to leadership cloning and intra-organization tribalism in toxic leadership teams. These conditions create an ideal situation for potential system-scale organizational dysfunction.

Keywords: Leadership; Management; Leadership Clone Theory; Tribalism; Organizational Development; Organizational Culture

Introduction

As I sat in a sports bar and grill, it was exhilarating to celebrate the touchdown that won the game and conference championship for my alma mater’s football team. Everyone in the small restaurant bar was cheering, and I found myself high-fiving people I had never met or spoken with in the past. We were, in the moment, part of something special, or so we felt we were. We were sharing a similar experience and laughing at those of us that taunted diners wearing the opposing team’s gear, innocent as it may have been. We were part of a tribe.

This is not uncommon. Human beings are a tribal species. Once people connect to a group, their identities become bound to that group and to the other members of that group. We see this in sports fanaticism, and in organizations such as fraternities, sororities, freemasonry, clubs, and teams. Although it appears innocent and fun in the pub, tribal behavior is not always harmless. People often become willing to help others, and even to put themselves in harm’s way or commit horrid acts for their groups [1]. Unfortunately, this also occurs in the workplace, and can be especially problematic in the leadership ranks, and particularly exacerbated when new leaders brought in or promoted from within a toxic and tribal organization adopt, or clone, the unsavory behaviors of their ineffective or dysfunctional leadership teams. Although many of us have witnessed or experienced tribal behavior in some way throughout our lives, this tribalism is rarely discussed in the realm of workplace teams and organizations, and especially not regarding the effects of this sociological construct on organizational leadership. However, this phenomenon of tribalism can have a significant effect on leadership, leader development, leader-member exchange, and organizational culture, and many leaders will fail to recognize it when it happens.

The purpose of this manuscript is to introduce and discuss the combination of Leadership Clone Theory (LCT) and organizational tribalism, and how LCT and the tribalization of new leaders can degrade organizational culture and ultimately organizational effectiveness.

Background and Discussion

Leadership

Leadership is a highly sought-after commodity in organizations, and it is one of the most written about topics in the literAbstract ature, whether peer-reviewed, academic text, or novel and handbook publications. The shelves in any large bookstore’s business section are filled with national literary bestsellers on the topic of leadership, although they often differ dramatically from one another, and often contradict other authors regarding leadership best practices. People in organizations and in public continue to wonder what makes a good leader, and there are many experts that will provide their opinions on the matter, often based on their own personal expertise, or even based on the increasing amount of research literature on the topic [2].

The popular quote is that leaders are those that get people energized and mobilized and get them moving [3]. In which direction? Although it may very well be the case that leaders mobilize their people, this commonly used definition does not consider the direction of mobility and does not define whether that leadership is good or bad, or effective or ineffective. In effect, the global scholarly literature exhibits that leaderships a complex topic and one that is based on and explained by a wide array of theoretical approaches, often resulting from studies performed by psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, theologians, organizational behaviorists, organizational development professionals, military scientists, and experienced leaders, among others, in an attempt to determine what makes a good leader and what separates him or her from a bad one.

It is probably safe to state, on the topic of leadership, that there is no definitive guide, no magic answer, no fantastic black box, and no individual leadership style that works effectively for every project, team, organization, or scenario. The historic theory, trait theory, examined the idea that individuals are born as natural leaders with the innate characteristics or qualities necessary to lead teams successfully [2]. Not only is there no evidence to support the idea that leadership is preordained and linked to DNA, there is evidence against that outdated argument [2,4]. Instead, Process Theory posits that leadership resides in the interactions of leaders with their scenarios, including their teams, and that leadership behavior can be learned through observation. Numerous leadership scholars hold to the concept that the best leaders are the best learners [2,4].

Leadership Clone Theory

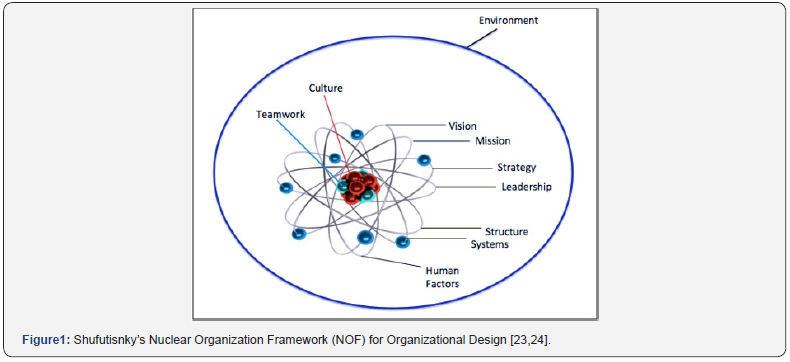

Leadership is critical to organizations, and the construct of leadership is exhibited in most organizational design models and frameworks, including the STAR Model, Jamieson’s Strategic Organization Design (SOD), and the Nuclear Organization Framework (NOF) model [5-8]. As such, leadership is a key element that interacts with other organizational factors, including organizational systems, structure, culture, strategy, teamwork, environment, and behavior, and thus organizational effectiveness. New leaders in organizations are often seen as the innovative lifeblood that can be instruments for real change in organizations and society [9]. Thus, it is no surprise that leadership training, preparation, experience, and mentorship are highly desired in organizations that plan to succeed.

Often, organizations hire external professionals with leadership experience in other companies, and often from competitor firms. However, it is not uncommon for professionals within the company to be promoted into managerial and leadership positions, often with no experience, education, or training in leadership positions. Furthermore, they are often hired into managerial and leadership positions based on technical success, scientific acumen, and even likeability or favor with the current organizational leaders. Although these are not all bad attributes for new leaders to have, and can often be commended, they do not readily translate into leadership or management ability [2].

A leader selected and elevated to a leadership position in this way is often considered to have assigned leadership, or leadership that is based on positionality rather than leadership ability. The exception is in the case of those that have been assigned leadership based on their influence, collaboration, and thirst for learning, among other characteristics that define emergent leadership [2]. Unfortunately, assigned leadership may often spell trouble for organizations that do not understand the appropriate means of leadership and manager development, and it is not uncommon for entire leadership teams to consist of assigned leaders with ineffective leadership characteristics over cyclical or generational periodicities in organizations as a result of poor leadership development models, methods, or succession programs.

Leadership emergence, based on Social Identity Theory, [10] defines the degree to which a person fits the identity of the group that he or she is selected to lead [2]. This is often why organizations choose, at least at face value, to hire or promote from within. One idea for this is that it is difficult to be an effective leader without a sense of what the followers need, and having come from the team of followers, the promoted leader should be able to function effectively as a leader within the group [11]. Although internal selectees for leadership positions may have the understanding and experience with the team and organization, organizational group dynamics can create complex and conflicted situations, and potentially hostile environments. Without the proper leadership guidance, training, and development, individuals thrust into leadership positions may adopt their direct example of leadership style and practice directly from those that have been or are currently their own leaders, even if the individual was aware of leadership problems prior to being promoted. This “cloning” behavior can particularly be seen in leadership teams that have hired the new leader, and often without the clear understanding that this phenomenon, Leadership Clone Theory (LCT), occurs subconsciously.

Clone Theory describes a scenario, conscious or subconscious, during which an individual promoted into a leadership role becomes indoctrinated into the current leadership team, environment, and behavior, and assumes a sort of mimicry of the current leaders. This situation can be positive in cases of successful, developed, and effective leadership teams. Likewise, this transformation can become a problem for the organization and for the individual and his or her career if the leadership team is not effective, functional, and healthy.

Often, when a respected high performer is selected for promotion into a management or leadership role, he or she will strive to perform at identical levels of success within the new role. Unfortunately, technical success, task knowledge and skill, and work ethic do not necessarily translate into leadership and managerial success [2]. However, people often learn from their leaders, regardless whether the example is positive or negative. Clone Theory occurs when individuals, due to purposeful or simply from experiential exposure, mimic the leadership and management behaviors and practices of the leadership team which they have become a part of.

Tribalism and Tribal Behavior

In some ways, humans are not so uncommon from some of the other primates we observe on television or in feature films. We’ve witnessed it growing up, with cliques that form in adolescence, in elementary school, high school, or other social circles, but it is not limited to these periods in life or these places. In all sorts of environments, people join and stick to groups, maintaining a social order, and once they connect themselves to a group, they can become strongly bound to it [1,12]. Although in many this can be positive, it can also cause problems in certain environments, including in the workplace. Humans are social by nature, and the social circles they form can be bound tightly enough to lead to inter-group relationships that are not only competitive, but sacrificial in a sense, often fostering a system of gratuity and aid to intra-group members while gratuitously penalizing members of external groups [1].

Human Instinct

When people think of tribes, their instinct is to think of primitive groups that hunted, lived, and fought together for a collective survival. These same individuals, although they may not realize it, often participate in tribal behavior or belong to tribes, although they may not define them as such due to a misplaced sense of sophistication of modern society. Nonetheless, these tribes or clans are powerful, and affect many behaviors, even subconsciously, that may be positive in some senses, but also create or drive social conflict and can be detrimental.

Studies have shown the tribal tendencies of human beings, including those that begin early in life. Chua [1] explains behavioral science studies performed on pre-school students in which they rapidly assimilated and adopted a tribe simply by being differentiated by T-shirt color, assigning preference and positive characteristics to those children that wore the same color T-shirts as they did, while simultaneously assigning more negative thoughts, or even remembering negative characteristics of those that were in the group that wore different color shirts.

Often, the result of such social environments can create rivalries, and even long-standing and unhealthy ones. Additionally, scientific research shows that the behavior that creates these rivalries can be physiologically reinforced through naturally occurring chemical release changes that can exacerbate the “enemy feeling” for out-group members, dehumanizing them and potentially reducing the natural empathy experienced when observing suffering [1,12].

In today’s “sophisticated” society, the areas of politics, international relations, and business are often described through the roles played by policy, economics, and even ideology, but little credence is given to the role that group identity and tribalism play in shaping human behavior in the context of these areas [1,12]. The differences in identity in different nations or cultures, their relative value and importance between countries and societies, and the way that these differences can affect beliefs, communication, behavior, and negotiation are often overlooked, and can have profound effects [1,13].

In fact, we have witnessed throughout history how group identity and tribal behavior can affect the geopolitical climate in conflict and war [1], but little attention is paid to the effects that this type of behavior can and often does have not only on corporations and agencies during mergers, acquisitions, and partnerships, but especially on interactions in teams within those organizations.

Tribal Behavior in Groups, Organizations, and Group Dynamics

Tribal behavior in organizations has a great deal to do with identity, including identity as individuals and group identity. Identity is a complex concept, and it can take numerous forms. Contemporary identity is often tied to features such as gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, ability, or sexual orientation, among others, with the understanding that individual identities are deeply inflected by these social features [14]. Nonetheless, identity extends beyond these features, into a multitude of individual and group features. In groups, these individuals must integrate the array of their features and differences that they represent. These individual differences, however, become closely linked to the group memberships of these individuals, making things more complicated

This is the paradox of identity, paradoxical because of the struggle of both the individuals and the group to establish a meaningful identity in which each individual and the group are integral parts of one another [15]. The more integrated the individuals become in the group, they are often increasingly bound, both consciously and subconsciously, to that group. This group loyalty or group tribalism, is a powerful force and remains powerful everywhere, including in organizations, and not just in primitive history as believed by many [12].

Tribalization of New Leaders and New Managers in Organizations

Logan et al. [16] have published research-based data that shows the benefits of their theory of Tribal Leadership, expressing that this natural phenomenon can be leveraged for the benefits of organizations, if it is properly employed, using their framework of five stages for deployment of the method. They posit that tribal behavior in companies can maximize productivity. Also, however, their text displays stages in which most organizational tribes find themselves, with either hostility, antagonism, resistance, and self-interest instead of a collaborative and engaging culture of partnership.

The authors’ work attempts to exemplify how organizations can utilize this natural phenomenon of tribal behavior to improve organizational function and effectiveness [16]. Nevertheless, the stages defined in the book, and the identification of where most organizations are, themselves imply how potentially problematic tribal behavior can be in organizations. To add to the statement that most organizations are at best in a stage of self-interest in which employees are antagonistic, resistant to change, hoard knowledge, see their co-workers as competitors instead of partners, and attempt to be seen individually as best and brightest [16], there are additional group dynamics that potentially transpire when intra-organizational tribes exist, and when there is a shift in affiliation, particularly to the leadership ranks.

In organizations, as fore-mentioned, culture is one of the critical elements that determines organizational success, effectiveness, and stability. Cultural differences affect the process of doing business and managing organizations [17]. Organizational culture consists of the common mindsets, values, and norms of behavior that have emerged over a time period and that most employees within the given organization share [6]. Just like culture affects other elements of an organization, these elements, such as systems, strategy, mission, vision, environment, organizational structure, and leadership affect culture [5,7,17].

Structure and leadership are the elements in an organization’s design that determine where formal power and authority are located, and how power is used [6]. Power and authority over decision-making very often lies with assigned leadership, and leaders exercise power differently, including the use of referent power, information power, reward power, and coercive power [2]. In her revered works, Mary Parker Follett described the natural urge and wish to keep balance of power [18] in order to keep a positive balance in organizations. However, not all leaders have this tendency, and not all leaders either have the experience or the knowledge to create this balance. Power can be wielded by individuals in different relational forms, specifically in the formats of power-over or power-with.

The power-over form is generally authoritarian or coercive in nature while the power-with form can be described as a jointly developed, co-active, and non-coercive power [19]. Although both can be used to achieve organizational goals, even common goals, this power-distance relationship affects intra-group and inter-group dynamics, LMX, and organizational culture, with the potential to create an “us versus them” relationship between different groups in organizations, particularly between leadership teams and staff. As such, power can be tribal, or be used in a tribal manner.

Thus, it makes sense why referent power, defined as the power that is based on followers’ identification and liking of their leader [2], is viewed as the most effective power use. It would not be inaccurate to say that power is tribal, fitting right into the characterization that tribalism is powerful. However, the dislike, distrust, disbelief, and perception of betrayal by leaders, can place leadership and staff at opposing ends of the spectrum, and generate inter-tribal conflict between the staff team and the leadership team.

New leaders are often less experienced at dealing with questions or issues of power distance and power distribution, as well as authority. New leaders are also, with no or very little preparation, thrown into situations that they are not experienced enough to handle while simultaneously being expected to perform successfully in this new role. With the real or perceived necessity to perform at high levels, new leaders are often placed in the precarious situation of having to choose a team when there is a conflict or tribalism between the staff and the leadership groups. This can be increasingly awkward when these leaders are internal and come from the ranks of the staff that they are now assigned to lead.

Position alone can place new leaders in a state of being perceived as “one of them,” when there is tribalism, with their previous colleagues now seeing or treating them as outsiders, and the expectation by leadership team members that the new leaders fall in line with the oft-espoused “one voice” of a leadership team, regardless of the virtue, transparency, or authenticity of that voice. And, with the expectation and the desire to excel, in addition to the subconscious dynamics of group identity, new leaders can become tribalized in their new occupational setting.

Leadership Clone Theory and Tribalism

One of the behaviors that often exacerbates the powerover relationship and creates or perpetuates poor LMX is the leadership’s lack of effective use of self as well as leaders’ withdrawn self-dishonesty (WSD) that can result in increased conflict and further separation between the staff and the leadership teams [20]. The inability for leaders to identify their own roles in culture and system breakdowns, or in intra-organizational tribal conflict, is problematic to say the least. This WSD element, paired with the rift between staff and leadership, acts to create two counter-cultures within a single organization, creating rivalries, with members of each of the cultures becoming tribal rivals. In an environment of intra-organizational, inter-team tribalism, there can be challenges and threats to organizations, especially when this scenario plays out between staff and leadership positioned in opposing tribes, and this can be increasingly tricky and delicate when there are staff members who are promoted or hired to the leadership team when these teams are in conflict.

In this scenario, particularly, new leaders promoted from within that have “clone-imprinted” into the toxic leadership tribe, often become viewed by their peers and colleagues as members of the out group, or even enemies as a result of organizational traitor assumption (OTA), a perception of betrayal of a previous identity group due to offers or conditions of personal gain. In this scenario, subordinates may become more likely to display resistance to leader requests and authority.

This combination of leadership cloning or leader clone imprinting, particularly in tribalistic toxic organizations can result in numerous threats to organizational performance through a potential combination of numerous ways, including:

(a) Creating or exacerbating hostility within the organization;

(b) Prompting or increasing distrust;

(c) Increasing conflict; and

(d) Creating a stressful work environment.

These factors can lead to additional problems, including but not limited to:

(a) Increased employee stress;

(b) A decline in job satisfaction;

(c) A reduction in focus;

(d) Employee absenteeism;

(e) Employee turnover; and even

(f) Employee violence.

Combined, LCT and tribalism cement at least two of the three sides of the toxic triangle being the destructive leaders and conducive environments portions [21]. As the SEAM approach explains, these conditions and the resulting factors listed above are not cohesive with productive work environments [22], and often result in lost productivity, decreased quality, increased rework, increased spending, and an overall decreased performance.

Effects on organizational design

This article explains how LCT and tribalism in new leaders serves in the degradation of organizational culture. As a result, the outcome may and likely will be much more drastic than cultural decline, because the culture of an organization is part of the systemic organizational lifeblood, and thus affects the other elements or factors, especially the culture-systems-structure continuum, that comprise and drive the organization. The NOF Framework of organizational design (Figure 1) displays the relationship of the organizational design factors and visually exhibits how LCT and tribalism in new leaders can, at the very least, interfere with optimal performance, and at the worst, potentially break down the organization [23,24].

The NOF model is like Jamieson’s Strategic Organization Design (SOD) model, however, it adds and replaces a few of the organizational design key elements in Jamieson’s model. The graphic of the model exhibits the inter-connectedness of the ten elements critical to organizational design and function. The figure also displays the dynamism of the model, showing the continuous movement, three-dimensionally, of each of the elements with reference to one another, and, in the spirit of the models’ visual structure of an atom, the energy that is potentially exchanged and changed when any of the elements are modified.

In the NOF model, the organization is represented by the chemistry graphic of an atom. Atoms are basically the core of any chemical as well as the constituents of matter and material changes observed in nature. An atom is composed of a nucleus, made up of protons and neutrons, and is surrounded by energy shells that house electrons. Depending on numbers and charge between the nucleus and electrons, the atom can have varying energy levels and in a matter of speaking, balance or lack thereof. Energy shifts can cause mutation in the nucleus, and this, though very basically described in this definition, determines the chemical element of the atom [23,24].

From the chemical model of an atom, we can see that the electrons in the outer shells or rings affect the nucleus, and that the changes in numbers of protons, neutrons, and electrons, and changes in the charges of electrons and protons, affect the energy, state, balance, and identity of the atom. Similar dynamics exist in organizations and are explained by the NOF model. In the NOF model of organizational design, changes in the elements of the organization, displayed in the core and the outer shells, can affect each other, including the culture and teamwork existing in the core, and will ultimately affect the energy, state, balance, and identity of the organization, thus disturbing organizational performance [23,24].

As fore-mentioned, organizational structure and organizational leadership are directly and predominantly implicated elements about power, LCT, and tribalism in this article, partially because they determine, in typical organization design, where formal power and authority are located, and how power is used [6]. Nevertheless, the effects of power, LCT, and tribalism do not end with leadership and structure, nor do they stop with the effects on organizational culture. These elements can affect the entire organizational design as they are all interconnected, and the changes are dynamic, so every change in energy or function of any element in the NOF model can influence some or all the other elements, including culture, structure, systems, teamwork, leadership, human factors, strategy, mission, vision, and environment.

Therefore, the affect that the leadership cloning and tribalism in an organization can have on culture will inherently disrupt the culture-structure-systems continuum, the other critical factors in the framework, and likely the organization’s overall productivity, quality, and performance.

Correcting the Course

Tribalism in organizations can become a threat that can fracture an organization from within. Indoctrinating new leadership into a toxic organization and influencing, even subconsciously, new leader adoption into the leadership team within such an organization can not only result in slowing of leader development in the group, but it can cause increased conflict, exacerbate hostility, and degrade organizational climate and culture. Furthermore, it can ruin a new leader’s ideas and experiences of leading and managing, and potentially destroy or redirect his or her career.

Preventing or addressing these concerns can be daunting. Tribalism exists in many societal circles, but it thrives in conditions of insecurity, volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity, lack of opportunity, and lack of upward mobility [1,12]. Leadership cloning thrives under similar conditions, but also under conditions of narcissism, hubris, WSD, and lack of established and structured professional leadership development, and these conditions in organizations are often generational, meaning that multiple leaders or even generations of leaders may have existed, operated, and survived under these conditions and may even understand such to be normal and prevalent across leadership teams. These are difficult situations and are often under difficult conditions, and work needs to be done to resolve the problems and to stem the mutual ignorance of intertribal toxicity.

Correcting and preventing the combined problems of LCT and tribalism cannot be done without hard work, courage, and the understanding and willingness of the stakeholders involved. The work has to be thorough and sustained and should consist of a minimum of a combination of organizational interventions, including openness to dialogue and constructive discourse, use of self as instrument, leadership development, and team building, as well as acceptance that third-party intervention may be necessary, such as third-party peacemaking, mirroring, and the Gestalt approach.

Self-as-Instrument, Reflection, and Self-Awareness

Being self-aware can be critical to the outcome of leadership on organizational behavior and work conditions. This is because being present as a self-aware person means being able not only to reflect on and learn from personal behaviors, thoughts, and actions, but also to be able to monitor these behaviors and actions in real-time, almost like an observer, as though an individual is able to step outside of the self and observe the current moment. Being able to be attentive to real-time experience and monitor and react to one’s own moment-to-moment being, with consciousness and awareness of the being, is often referred to as presence, and the act of doing so is called presencing [18,25].

This present, self-awareness is key to leadership and can allow new leaders to leverage it in ways that will drive professional reinvention and self-development. It is argued by some experts that self-awareness is the fundamental foundation of any effective leadership program [9]. To speed up the ranks, managers and leaders often miss this, failing to take the time for introspection and the learning of self in reference to others and to the mission, vision, and values of the organization that comes with it.

In the 20th century, the NTL Institute was well known for the facilitation of T-groups. This applied behavioral science intervention brought considerable attention to self-awareness, feedback, and interpersonal and group dynamics, helping to anchor the ability for individuals in organizations to reflect on the self in order to understand their own behavior and the impact it has on others and on their organizations [9,26,27].

Today, the use of self, or self-as-instrument as it is often called, enables the engagement of personal emotional, physical, and spiritual aspects in the moment and in different situations [27]. This practice is the connecting fabric of the concepts of selfawareness, choices, and actions as the fundamental infrastructure of our capacities to be effective change agents [28]. Use of self includes a capacity for reflection, feedback, and a close look at what occurs when we attempt to influence problems, people, or situations. It is a vital element of knowledge and practice for the role of the change agent, [27,28] which is the role that is commonly filled by team managers and leaders. That resulting level of awareness of presence and being is key to driving solutions and effective change.

Use of self is potentially effective for many purposes, including diagnosing emotional reactions, initial perceptions, understanding bias, postponing judgment, and belaying images and fantasies [9,27,29] thus enabling the awareness of one’s own biases, in real-time. Tannenbaum and Hanna [30] summed up use of self-as-instrument succinctly, stating that it requires social sensitivity, the ability to accurately assess the environment, and having a high degree of action flexibility, depending on situation.

Working with the unconscious self can be complex, difficult, and may feel uncomfortable or even intolerable to some leaders, but acknowledging unconscious forces can be a critical step in enlarging possibilities of understanding individual behaviors and how they translate to the organization, as well as providing feedback on one’s own behavior [28], which is vitally necessary for new leaders and managers. New leaders’ use of self as instrument could be beneficial for recognizing their roles in hostile or toxic environments, alleviating WSD, helping them de-clone from the bad leadership behaviors, correcting the perception of OTA, and making efforts to repair the tribal rift between staff and leaders within organizations.

Improved Situational Awareness through Visual Intelligence

One of the key practices and fundamental interventions in OD practice is the use of action research. In this process, the OD professional works through broad observation in order to identify and diagnose the organizational problems that exist. Many problems may appear obvious and are discussed and described through interviews or statements by team members, customers, and other stakeholders. However, some practitioners are more successful and effective than others, and part of this can be attributed to the ability to pay attention to, see, and analyze details. Visual intelligence is a method to thoroughly and intentionally observe the picture, situation, or environment surrounding individuals, and to be able to see and pay closer critical and analytical attention to what is right in front of them [31].

The idea of visual intelligence in not to try to look beyond what people see, but rather, in the fashion of the literary character of Sherlock Holmes, to take a deeper dive into what is right in front of them, to analyze the scenario from every angle, and to pull new or more detailed meaning from it, thus better observing their situations and finding, describing, and defining the fine data [6,23,24,31]. Very often, people see the scenario or surroundings that are right in front of them, but do not see or interpret the details in the scenario or the picture, and as a result, they miss the cues that could inform them of answers, flaws, failures, or problems to come.

This inability to truly see what is directly in front of you is termed inattentional, perceptual, or unintentional blindness, and this phenomenon suggests that when the focus is exclusively on a specific part of a task, concept, behavior, or image, the other details tend to fade into the background or into obscurity, regardless of whether they are in plain view [31]. Furthermore, most people do not believe that they experience this because they lack the awareness of it and, as fore-mentioned, the personal useof- self-as-instrument skills to recognize this.

Visual intelligence prompts us to observe, in every scenario or picture, the who, what, when, and where, to deeply and thoroughly analyze the scenario from every street corner [32], and to avoid perceptual filtration that leads to confirmation and cognitive biases and tunnel vision. This is not only so in OD practice, but is a highly espoused skill or characteristic for most professions and has been shown to be vitally beneficial in the practice of law enforcement, medicine, intelligence analysis, and military operations [7,23,24,31]. This is a critical skill for managers because it affords the opportunity for continual gathering of vital information through observation and deduction from details, and aids in differentiation between subjective and objective observation, which in turns allows more accurate and true interpretation of data [7,23,24].

This can help managers better understand the scenario unfolding before them, can allow them to better hone emotional intelligence, and can provide them with a means of averting disaster as well as serving as a precursor to great discovery. The Sherlock Holmes within us is a useful skill that can aid in effective communication, situational awareness, and better decisionmaking as leaders [7,23,24,31].

Leadership development

OD has a long history of providing leaders with the means to build or refocus organizations for success, including development or modification of strong and positive cultures, and positive transformation of organizations through effective change processes. Therefore, it is important and beneficial for leaders in organizations to have a background of OD or an education and expertise with stronger emphasis on OD, with skills to initiate, educate, lead, and sponsor change [33]. There are numerous ways to prepare leaders, and it cannot be done over a short period of time. However, there are principles and practices in leadership that can be provided through coaching, education, and training, including:

(a) Participation in T-Groups or Human Interaction Laboratory sessions;

(b) Receiving Emotional Intelligence training;

(c) Receiving cultural intelligence [34] training; and

(d) Receiving Use of Self as Instrument training.

Furthermore, new leaders should receive leadership education and training, with an understanding not only of the internal systems and structures of the organizations, but with an education on the fundamentals of leadership theory and principles, including topics and theories such as:

(a) Situation Leadership Approach

(b) Path-Goal Theory

(c) Transformational Leadership

(d) Authentic Leadership

(e) Servant Leadership

(f) Adaptive Leadership

(g) Psychodynamic Approach to Leadership

(h) Appreciative Inquiry

(i) Leadership Assessment

(j) Foundations of Organization Design and

(k) LMX

Additional activities for leadership development could include third-party intervention in order to assess leadership concerns, problems, failures, and areas of improvement with activities ranging from the basic SWOT analysis to the use of a facilitated Gestalt orientation approach or the use of the Based on A True Story (BOATS) leadership analysis and development model [7,23,24].

Team Building

It is no secret that teams outperform individuals (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993), which is why it is necessary to prevent the intraorganizational tribalism and conflict discussed throughout this manuscript. Strong teams are highly committed to their purposes goals, and approaches to meet the organizational missions and visions Katzenbach & Smith, 1993. As fore-mentioned, tribalism, and the problems that rise with LCT and tribalism in toxic environments, threaten organizational teamwork, and therefore are at least a hindrance and likely a danger to organizational performance.

Thus, when scenarios of LCT and toxic tribalism exist, it is necessary to intervene. In order to attempt to correct and reverse some of the damage organizations have already created through toxic and hostile environments, and to curb any hostile intraorganizational tribalism, the leadership and staff teams in such scenarios should undergo a series of team building initiatives and interventions together, including third-party interventions. These could include exercises on Katz & Miller’s 4 Keys [32], Schein’s Cultural Analysis, Denison’s Organizational Culture Inventory, appreciative inquiry, stream analysis, Lewin’s force field analysis, and mirroring [35], among other possibilities. However, the best method to deal with the problems of LCT and intra-organizational tribalism is by preventing them through comprehensive leadership development and employee development programs that work.

Conclusion

New leaders are vital to organizational continuity, as experienced leaders retire, leave for other opportunities, are promoted, or when new positions are created due to restructuring, mergers and acquisitions, or organizational growth. Organizational human resources talent acquisition methods differ, but, new managers and leaders are often recruited through a diversity of pathways, including externally and from within the departments that require new management. New leaders from each pathway will face challenges, but when comprehensive leadership development is not implemented in organizations, new leaders and managers can face numerous obstacles [36].

This article discusses the interconnected nature of organizational leadership, culture, structure, and systems, among other elements, and how they can be affected by certain conditions and behaviors as well as how they affect organizational outcomes. This includes leadership behaviors, structures, and cultures that pre-date new leader arrival or promotion. Although organizational structures exist, with assigned authority, it is no secret in human resources science that organizational cultures can be problematic in organizations with traditional top down, bureaucratic-style structures, and that team subcultures often form, separating departments into staff and leadership teams with individual group cultures. Inherent to human psychological and social systems, tribalism will occur in these group or team cultures and this can be particularly problematic when the workplace is even mildly hostile and where toxic leadership exists. These conditions create an ideal situation for potential system-scale organizational dysfunction [37].

In such an environment, new leaders can have trouble, and their indoctrination into such an environment can often lead to leadership cloning of ineffective leadership styles and methods. When combined with tribalization, this scenario can give way to increasingly hostile cultures, and affect organizational systems, teamwork, behaviors, strategy, and environment, likely Impeding productivity and degrading quality and performance [38]. As a means of preventing such scenarios, it is critical that comprehensive and effective leadership development programs be implemented for new and existing leaders, and that the development programs include certain experiential necessities, such as use of self as instrument, dialogue, organizational assessment, and openness to critical third-party intervention when necessary.

References

- Chua A (2018a) Tribal World: Group Identity is All. Foreign Affairs 97(4): 25-33.

- Northouse PG (2016) Leadership: Theory and Practice (7th edn.), Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- Kouzes J, Posner B (2012) The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations (5th edn.), Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Kouzes J, Posner B (2010) The Truth About Leadership: The No- Fads, Heart-of-the-Matter Facts You Need to Know. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA

- Jamieson DW (2017) Strategic organization design-Overview. Lecture Presentation, Cabrini University, Organizational Development Program, Radnor, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Kates A, Galbraith JR (2007) Designing Your Organization: Using the STAR Model to Solve 5 Critical Design Challenges. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Shufutinsky A (2018a) Attention to Detail: A Book Review of Amy Herman’s Visual Intelligence. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies 5(2).

- Worley CG, Hitchin DE, Ross WL (1996) Integrated Strategic Change: How OD Builds Competitive Advantage. Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA.

- Gallagher DP, Costal J (2012) The Self-Aware Leader: A Proven Model for Reinventing Yourself. ASTD Press: Alexandria, VA, USA.

- Hogg MA (2001) A Social Identity Theory of Leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review 5(3): 184-200.

- Goffeer R, Jones G (2006) Why Should Anyone Be Led by You? What it Takes to be an Authentic Leader. Harvard Business Review: Boston, MA, USA.

- Chua A (2018b) Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations. Bloomsbury: New York, USA.

- Hofstede G, Hofstede GH, Minkov M (2010) Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGraw Hill: New York.

- Appiah KA (2005) The Ethics of Identity. Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

- Smith KK, Berg DN (1987) Paradoxes of Group Life: Understanding Conflict, Paralysis, and Movement in Group Dynamics. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Logan DC, King JP, Fischer Wright H (2008) Tribal leadership: Leveraging natural groups to build a thriving organization. Harper Collins: New York, USA.

- Trompenaars F, Hampden-Turner C (2012) Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business (3rd edn.), McGraw Hill: New York, USA.

- Shufutinsky A, Long B (2017) The Distributed Use of Self-as- Instrument for Improvement of Organizational Safety Culture. OD Practitioner 49(4): 36-44.

- Metcalf HC, Urwick L (2013) Dynamic Administration: The Collected Papers of Mary Parker Follett/Martino Publishing: Mansfield Centre, USA.

- Shufutinsky A, Cox R, Vizcarrondo ME (2017) The Collapse of Sensemaking in Injury Root Cause Investigations Resulting in Ineffective Injury Prevention Decision-Making: A Retrospective Case Study. Juniper Online Journal of Public Health 2(2): 1-11.

- Padilla A, Hogan R, Kaiser RB (2007) The Toxic Triangle: Destructive Leaders, Susceptible Followers, and conducive environments. The Leadership Quarterly 18(3): 176-194.

- Savall H, Zardet V (2015) Reflecting on SEAM in the 21st Century: New Ideas, New Adventures. In: The Socio-Economic Approach to Management Revisited: The Evolving Nature of SEAM in the 21st Century, Anthony F Buono, Savall H (Eds.), IAP: Charlotte, NC, USA.

- Shufutinsky A (2018b) Ergonizational Development: Ergonomics as an OD Intervention. Submitted and under review for publication by OD PRACTITIONER.

- Shufutinsky A (2018c) The Dynamic Organizational Design Framework: Defining the Elements of Organizational Assessment and Design. Critical Thinking Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA.

- Senge P, Scharmer CO, Jaworski J, Flowers BS (2004) Presence: Human Purpose and the Field of the Future. Crown Business: New York, USA.

- Bradford LP, Gibb JR, Benne KD (1964) T-Group Theory and Laboratory Method. Wiley & Sons: New York, USA

- Jamieson DW, Auron M, Shechtman D (2010) Managing ‘use of self for masterful Professional Practice. OD PRACTITIONER 42(3): 4-11.

- Seashore CN, Shawver MN, Thompson G, Mattare M (2004) Doing good by knowing who you are: The instrumental self as an agent of change. OD Practitioner 36(3): 42-46.

- McCormick DW, White J (2000) Using One’s Self as an instrument for organizational diagnosis. Organization Development Journal 18(3): 49-61.

- Tannenbaum R, Hanna R (1985) Holding on, letting go, moving on: Understanding a neglected perspective on change. In: Tannenbaum NR, Mar-gullies, F Massarik (Eds.), Human system development. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Herman A (2016) Visual Intelligence: Sharpen Your Perception, Change Your Life. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Katz JH, Miller FA (2013) Opening Doors to Teamwork & Collaboration: 4 Keys that Change Everything. Bennett-Koehler: San Francisco, USA.

- Warrick DD (2018) The Need for Transformational Leaders that Understand Organization Development Fundamentals. OD PRACTITIONER 50(4): 33-40.

- Livermore DA (2009) Cultural Intelligence: Improving Your CQ to Engage Our Multicultural World. Baker: Grand Rapids, Michigan.

- French WL, Bell CH (1999) Organization Development: Behavioral Science Interventions for Organization Improvement (6th Ed.), Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA.

- Cheung-Judge M, Jamieson DW (2018) Providing Deeper Understanding of the Concept of Use of Self in OD Practice. OD PRACTITIONER 50(4): 33-40.

- Conbere J, Heorhiadi A (2011) Socio-economic approach to management. OD PRACTITIONER 43(1).

- Conbere J, Heorhiadi A (2015) Why the socio-economic approach to management remains a well-kept secret. OD Practitioner 47(3): 31-37.