“Stone” Performance: Toward Psychological Skill Optimization

Ducasse Déborah1,2*, Olié Emilie1,2,3 and Courtet Philippe1,2,3

1Department of Emergency Psychiatry & Acute Care, France

2 Inserm, France

3University of Montpellier UM1, France

Submission: December 06, 2018; Published: December 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Déborah Ducasse, Department of Emergency Psychiatry & Acute Care, Lapeyronie Hospital Montpellier, France.

How to cite this article: Ducasse D, Olié E, Courtet P. “Stone” Performance: Toward Psychological Skill Optimization. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2018; 10(2): 555787. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2018.10.555787.

Abstract

In February of 2017, the French artist Abraham Poincheval entombed himself in a 12-tonne limestone boulder for an artistic performance entitled “Stone” (Palais de Tokyo, Paris). Our interest in innovative therapeutic interventions in suicidal behaviour, particularly positive psychology, led us to interview the artist in order to highlight the psychological skills that allowed him to “survive“ such extreme conditions. Positive psychology aims to identify the cognitive skills involved in optimal human functioning, and this is a promising research area for suicidal behavior management. During this performance, Abraham Poincheval showed optimal psychological skills to adapt to an unfamiliar and adverse environment. Abraham Poincheval’s feedback on his incredible experience highlighted two main optimal psychological skills that we should keep in mind in our daily practice of psychiatry: the acceptance of inner experiences and the pursuit of intrinsic motivational meaningful commitments. This unique artistic performance brings to light an empirical phenomenological experience.

Keywords: Performance art; Emotion regulation; Optimal human functioning; Adverse environment; Motivation

Introduction

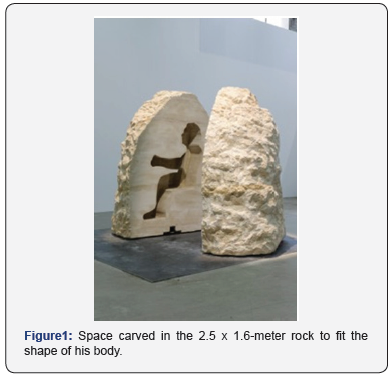

“Be self-aware, try to get an idea of your own geography” Abraham Poincheval. In February of 2017, the French artist Abraham Poincheval entombed himself in a 12-tonne limestone boulder for an artistic performance entitled “Stone” (Palais de Tokyo, Paris). For a whole week, he stayed in a space carved in the 2.5 x 1.6-meter rock to fit the shape of his body (Figure 1). He was connected to the outside world by a simple ventilation duct. He could perform few movements and had access to small niches that contained food and drinks. Visitors to the Palais de Tokyo could follow what was happening in real time via a monitor connected to an infrared camera inside the stone. His presence and the possibility to see him without being seen favored two main daily-life interactions:

a) The search of human contact in the hope of sharing their suffering (“people who talk to you about their love life”).

b) The search of human contact for sharing love and inspirational relationships (“people who read poems to you”).

But how did Poincheval cope with the intense stress (pressure, strain) caused by isolation and physical/emotional distress? Our interest in innovative therapeutic interventions in suicidal behaviour, including psychotherapeutic approaches, particularly positive psychology, led us to interview the artist in order to highlight the psychological skills that allowed him to “survive“ such extreme conditions. Indeed, positive psychology based-psychotherapy aims to identify the cognitive skills involved in optimal human functioning, and this is a promising research area for suicidal behavior management [1] From our point of view, during this art performance, Abraham Poincheval showed optimal psychological skills to adapt to an unfamiliar and adverse environment. Therefore, we interviewed him to understand the psychological processes underlying this astonishing performance.

Abraham Poincheval had to deal with fear related to the hostile context, raising the question of how he efficiently managed unpleasant inner experiences. Interestingly, Abraham Poincheval specified: “fear was not different from the one I face in daily life”. Everybody has to deal with unpleasant emotions when stressful life events occur, or when attempting to act outside the comfort zone. Individuals with psychiatric disorders, including suicidal patients, are especially used to struggle against negative feelings, and often try to avoid them (i.e., experiential avoidance) [2]. This avoidance behavior is a maladaptive coping strategy that reinforces invasive painful experience or psychological pain [3]. Suicidal ideation or acts could represent extreme experiential avoidance strategies [4].

Abraham Poincheval explained fear management as follow: “do not stiffen against but be flexible to fear… breath and let it pass”. Indeed, for effective emotional regulation, it could be important to be able to accept inner experiences, whatever their valence, through mindfulness skills (i.e., to be aware of physical sensations sustained by emotions, to be able to notice and label them in order to allow them to exist and move away) [5]. Acceptance involves awareness, curiosity and self-compassion towards private inner experiences now [6]. Mindfulness and self-compassion might lead to better emotion regulation skills concerning self-related emotions [7,8].

At the neural level, it has been shown that such skills are related to activation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC) in long-term meditators but also in meditation-naive participants [9]. During the Stone performance, Abraham Poincheval’s non-reacting attitude towards inner experiences (without any specific training) could have facilitated DMPFC activation: “Meditation? I do not know what it is…I have an easy routine: every day I spend at least ten minutes watching one thing without doing anything else”.

Abraham Poincheval’s psychological processes are like those learned in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). ACT aim is to decrease experiential avoidance and increase psychological flexibility [10].

This should help patients:

a) To accept unavoidable innate/private events, by noticing them as transient mental events that are different from the self, or as Abraham Poincheval explained in his own words: “do not stiffen against, but be flexible to [fear]”, “breath and let it pass”. Notably, breathing does not have to be understood as an attempt to modify the current inner experience, but rather as a permanent anchor to the present moment through which experience can exist and change. Abraham Poincheval, then, used the term of “sweetness” (smoothness, harmony, comfort) to refer to the experience.

b) To identify what is important in one’s life [10], to improve the intrinsic motivation to engage in meaningful actions [11]. Interestingly, Abraham Poincheval stressed the difference between the present time in which he is engaged in meaningful actions and his teenager years when: “ I could spend a lot of time waiting for something that could not come because I think I did not even know what I wished could happen in my life”. As a result, during the “Stone” performance he was entirely involved in the present action and he did not have to deal with boredom, because he was connected to the meaning of the present experience (in his own words: “discover”, “having fun”, and “surpassing himself”). The main values highlighted by this experience are the same values that drive his entire life (“What is driving my life? Rebounding, whatever it is”).

According to the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), intrinsic motivation refers to the spontaneous tendency ‘‘to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise one’s capacity, to explore, and to learn’’ [12] (“Do not be satisfied with what one is allowed to see of the world, but rather experience personally the world”, Abraham Poincheval). It leads to specific affective states, such as interest, curiosity and fun. Moreover, many experimental and field studies have demonstrated that intrinsic motivation is associated with enhanced learning, performance and creativity [13]. The close relation between the SDT concept of intrinsic motivation and Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of flow [14] has been noted for a long time [12]. The flow theory [14] is a particularly useful and dynamic framework for characterizing the quality of one person’s engagement in an activity or task.

Flow is conceptualized as a heightened state of engagement, characterized by the following phenomenological aspects: emerging of action and awareness (i.e., all attention is focused on the relevant stimuli), intense concentration and absorption, perception of being in control, loss of self-consciousness, and transformation of time (i.e., time seems to fly). Abraham Poincheval referred to his phenomenological experience during the Stone performance as the “perfect rhythm”, “osmosis” (being one with the experience), and “being in the present moment”.

He specified that “To imagine living at another speed, in another temporality” was an intrinsic motivation for this performance. Like for intrinsic motivation, when people experience flow, their satisfaction and fulfillment are inherent to the activity itself and their behavior is ‘‘autotelic’’ (auto = self, telos = goal), or performed for its own sake. Like SDT, the flow theory emphasizes the phenomenology of intrinsic motivation. The flow theory is related to the optimal challenge and ensuing competence satisfaction associated with intrinsic motivation [15]. Intrinsic (as opposed to extrinsic) motivation has been associated with increased well-being and satisfaction with life [16]. It has been suggested that people seeking greater wellbeing would be well advised to focus on the pursuit of goals involving growth, connection, and contribution rather than goals involving money, beauty, and popularity, and of goals that are interesting and personally important to them rather than goals they feel forced or pressured to pursue [17]. Similarly, Abraham Poincheval linked happiness to the pursuit of challenging and meaningful performances.

Conclusion

Abraham Poincheval’s feedback on his incredible experience highlighted two main optimal psychological skills that we should keep in mind in our daily practice of psychiatry and communicate to our patients: the acceptance of inner experiences and the pursuit of intrinsic motivational meaningful commitments. Abraham Poincheval pointed out that meaningful experiences are always profitable, leading to increased self-awareness and knowledge. This unique artistic performance brings to light an empirical phenomenological experience. Abraham Poincheval has spontaneously developed psychological skills that might be useful to improve psychiatric therapeutic strategies. “Human beings are fascinating and still to be probed and as deep as space” (Abraham Poincheval).

References

- Wingate LR, Burns AB, Gordon KH, Perez M, Walker RL, et al. (2006) Suicide and positive cognitions: Positive psychology applied to the understanding and treatment of suicidal behavior. Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy 261-283.

- Nielsen E, Sayal K, Townsend E (2016) Exploring the Relationship between Experiential Avoidance, Coping Functions and the Recency and Frequency of Self-Harm. PLoS One 11(7): e0159854.

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K (1996) Experimental avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 64(6): 1152-1168.

- Luoma JB, Villatte JL (2012) Mindfulness in the Treatment of Suicidal Individuals. Cogn Behav Pract 19(2): 265-276.

- Condon P, Desbordes G, Miller WB, DeSteno D (2013) Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science 24(10): 2125-2127.

- Kabat Zinn J (2005) Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. 10th (edn.), Hachette Books, USA.

- Cooper D, Yap K, Batalha L (2018) Mindfulness-based interventions and their effects on emotional clarity: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Affect Disord 1(235): 265-276.

- Grecucci A, Pappaianni E, Siugzdaite R, Theuninck A, Job R (2015) Mindful Emotion Regulation: Exploring the Neurocognitive Mechanisms behind Mindfulness. Biomed Research International 2015: 9.

- Lutz J, Herwig U, Opialla S, Hittmeyer A, Jäncke L, et al. (2014) Mindfulness and emotion regulation--an fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9(6): 776-785.

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J (2006) Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther 44(1): 1-25.

- Niemiec CP, Ryan RM, Deci EL (2009) The Path Taken: Consequences of Attaining Intrinsic and Extrinsic Aspirations in Post-College Life. J Res Pers 73(3): 291-306.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55(1): 68-78.

- Di Domenicon SI, Ryan RM (2017) The Emerging Neuroscience of Intrinsic Motivation: A New Frontier in Self-Determination Research. Front Hum Neurosci 24(11): 145.

- Csikszentmihalyi M (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. York, NY: Harper and Row, USA.

- Ma Q, Pei G, Meng L (2017) Inverted U-Shaped Curvilinear Relationship between Challenge and One’s Intrinsic Motivation: Evidence from Event-Related Potentials. Front Neurosci 28(11): 131

- Sheldon KM, Ryan RM, Deci EL, Kasser T (2004) The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: it’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30(4): 475-486.

- Shneidman ES (1993) Suicide as psychache. J Nerv Ment Dis 181(3): 145-147.