Does Community Surveillance Mitigate by-Catch Risk to Coastal Cetaceans? Insights From Salmon Poaching and Bottlenose Dolphins in Scotland

James RA Butler1*, Simon A McKelvey2 , Iain AG McMyn3 , Ben Leyshon4 , Robert J Reid5 and Paul M Thompson6

1 CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, Australia

2 Conon District Salmon Fishery Board, UK

3Kyle of Sutherland District Salmon Fishery Board, UK

4 Scottish Natural Heritage, UK

5 Scottish Agricultural College Veterinary Services Division (Inverness), UK

6University of Aberdeen, UK

Submission: February 05, 2017; Published: June 01, 2017

*Corresponding author: James RA Butler, CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, GPO Box 2583, Brisbane, QLD 4001, Australia

How to cite this article: Butler JRA, McKelvey SA , McMyn IAG, Leyshon B. Does Community Surveillance Mitigate by-Catch Risk to Coastal Cetaceans? Insights From Salmon Poaching and Bottlenose Dolphins in Scotland. Fish & Ocean Opj. 2017; 3(1): 555603. DOI: 10.19080/OFOAJ.2017.02.555603

Abstract

By-catch in gill net fisheries is a major threat to populations of small coastal cetaceans, but there are no published examples of communities tackling illegal fisheries responsible for by-catch. In the Inner Moray Firth Special Area of Conservation (SAC), Scotland, protected bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) were caught in poachers’ gill nets set for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and sea trout (S. trutta) in the 1990s. In response, the 2001 SAC management plan recommended the implementation of an experimental community-based poaching surveillance scheme. ‘Operation Fish Net’ (OFN) was established in 2002 as a partnership between statutory and non-statutory stakeholders in dolphin conservation, marine wildlife tourism and salmon fisheries. OFN mobilised tourists and local communities to report illegal netting activity to statutory authorities for investigation. In this paper we evaluate the impact of OFN. Based on principles of community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) we suggest that OFN created a deterrent by intensifying surveillance effort. However, we identify other factors which may also have influenced poachers’ behaviour, highlighting the inherent difficulties of evaluating CBNRM. OFN demonstrated several design principles for effective CBNRM, including a cross-scale and multi-stakeholder adaptive co-management network and an economic incentive for stakeholders to conserve dolphins and salmon generated by tourism and recreational fisheries. We suggest possible improvements to OFN, and future considerations for the evaluation of community-based fisheries management.

Keywords: Adaptive co-management; Bottlenose dolphins; By-catch; Evaluation; Illegality; Poaching; Special Area of Conservation; Salmon

Introduction

Incidental entanglement (‘by-catch’) in gill net fisheries is one of the greatest anthropogenic threats to populations of small cetaceans worldwide [1], and coastal and freshwater populations are particularly impacted [2]. Examples include Hector’s dolphins (Cephalorhynchus hectori) in New Zealand [3,4], Irrawaddy river dolphins (Orcaella brevirostris) in the Mahakam River, Kalimantan [5], and botos (Inia geoffrensis) and tucuxis (Sotalia fluviatilis) in the Amazon River [6].

While strategies can be implemented in commercial gill net fisheries to mitigate the threat they pose to cetaceans and other marine mammals [2,7,8], small-scale artisanal and illegal fisheries require a different approach due to their generally unregulated or clandestine nature [9,10]. In coastal or freshwater locations, community-based strategies may be one feasible option due to the close proximity and associations between cetacean and human populations. However, while there are instances of communities retrieving and monitoring fishing debris to protect marine fauna (e.g. discarded nets in northern Australia) [11,12], to our knowledge there are no published examples of community-based initiatives targeting illegal fisheries which threaten marine mammals. Consequently there is little published experience of the efficacy of this strategy, or insights with which to design and evaluate similar schemes.

Because it empowers local stakeholders to manage resources which they utilise, community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) has gained interest internationally as a potential panacea for mitigating anthropogenic threats to biodiversity and endangered species [13,14], including the illegal exploitation or ‘poaching’ of natural resources [15-19]. One model of CBNRM established in the 1980s and 1990s is the ‘enterprise approach’, which became the foundation for integrated conservation and development projects in developing countries, usually related to protected area management. Under this model alternative livelihoods are introduced which depend upon species or habitats of concern, thus generating an incentive for communities to protect them, creating a synergy between conservation and livelihoods [20,21]. Linked enterprises often involve the sustainable utilisation of wildlife, for example through consumptive and non-consumptive tourism [22-28].

Armitage (2005) and Berkes (2007) subsequently argued that successful CBNRM is not determined by the implementation of ‘blue-print’ models such as the enterprise approach, but by the evolution of multi-scale partnerships and flexible governance networks tailored to the unique local social-ecological context. Similarly, common-pool resource theory suggests that while there are fundamental design principles for establishing effective CBNRM [29], there are no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions [30,31]. These are also characteristics typical of adaptive comanagement, where cross-scale institutions and social networks evolve amongst stakeholders in response to a resource crisis, combining management experimentation with iterative colearning and power-sharing suited to the local social-ecological system [32-36].

This paper evaluates CBNRM of coastal cetaceans and illegal gill net fisheries in the Moray Firth, north-east Scotland, in 2002-2008. The region contains the only resident population of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) remaining in the North Sea [37], with approximately 195 animals using the Firth and other areas of the east coast [38]. Bottlenose dolphins are protected under the UK’s Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004, and the killing of a dolphin is a prosecutable offence. They are also listed in Annexes II and IV of the 1992 European Commission Habitats Directive (Council Directive 92.43/EEC) and are therefore considered threatened in a European context, and a European Protected Species requiring elevated levels of protection. Under the Directive governments are required to establish Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) for listed species, and in 1995 the Inner Moray Firth was designated an SAC to protect the dolphin population [39]. Dolphins are an iconic species in the Moray Firth, and since the 1980s the population has been the primary attraction for a growing marine wildlife tourism industry [40].

Rivers flowing into the Moray Firth support populations of anadromous Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and sea trout (S. trutta). During the 1990s there was concern about the status of some salmon sub-stocks in these rivers, with several failing to attain conservation targets of spawning adults over successive years [41]. Salmon and sea trout support recreational rod and commercial coastal net fisheries. While the netting industry has declined since the 1980s, rod fisheries have become increasingly popular, attracting anglers from across the UK and overseas [42,43], generating £28.8 million through angler expenditure in the Moray Firth in 2003 [44]. As throughout Scotland [43], salmon and sea trout poaching has been a long-established activity in the Moray Firth.

In 2001 the Inner Moray Firth SAC management plan identified three direct anthropogenic threats of mortality or injury to dolphins: boat collision, underwater explosions and entanglement in fishing gear and marine debris [44]. The latter was due to the confirmed by-catch and drowning of dolphins in salmon poachers’ gill nets. Based on a preliminary risk assessment, the plan considered that the likelihood of further by-catch was ‘moderate’. The consequence of by-catch was considered ‘severe’ because a population viability assessment suggested that the additional death of one adult female per annum from anthropogenic causes would decrease the median time to quasi-extinction to 29 years [45]. In response to this threat, the SAC management plan recommended that a community-based surveillance scheme should be trialled to enable dolphin-watching tourists, tour operators and local community members to report suspected poaching activity and illegal nets to statutory authorities.

In this paper we describe and evaluate the scheme in 2002-2008. We attempt to identify the factors responsible for its apparent suppression of poaching effort and reduction of by-catch risk in terms of principles for effective CBNRM, and illustrate the difficulty of isolating these from other potential drivers of poachers’ behaviour. Based on our results we discuss how the scheme could be improved to sustain its efficacy, and provide insights for the design of similar community-based strategies aiming to mitigate threats to coastal cetaceans from illegal or other unregulated fisheries.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The Moray Firth (58° N, 3° W) is a large embayment in north-east Scotland with an area of approximately 5000km2. Between the extremities of Duncansby Head to the north and Fraserburgh to the east the coastline length is 523km (Figure 1). Seventeen major rivers drain into the Firth. Fisheries for salmon and sea trout are managed by statutory District Salmon Fishery Boards (DSFBs) under the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act (2003). DSFBs have delineated jurisdictions over catchments and up to 5km seaward from the mean low water spring tide line. They employ bailiffs with powers of arrest to apprehend and deter poachers through routine foot, vehicle and boat patrols of their catchment and coastal jurisdictions [43]. At the time of the study there were 12 DSFBs in the Moray Firth.

Operation fish net

Instigated by the Inner Moray Firth SAC management plan, a Wildlife Officer of the Highland Constabulary convened a series of meetings in 2001 between representatives of statutory and non-statutory stakeholders in the Moray Firth to design a trial community surveillance scheme, named ‘Operation Fish Net’ (OFN). Statutory bodies were the Grampian Police, Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH), the Scottish Fisheries Protection Agency (SFPA) and the 12 Moray Firth DSFBs. Primary nonstatutory stakeholders involved in the planning were the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, the Scottish Agricultural College and the nine boat and two land-based marine wildlife tour operators active in the Moray Firth. Other non-statutory stakeholders were tourists, local communities and salmon fishery owners (Figure 2).

The scheme established a network of information-sharing and resourcing (Figure 2). Tourists, tour operators and local communities reported sightings of suspected poaching activity and illegal nets via a ‘free-phone’ telephone service hosted by one of the partners, who wished to remain anonymous to avoid retribution from poachers. These details were immediately relayed to the relevant DSFB bailiffs in whose jurisdiction the incident occurred for investigation. The Highland and Grampian police supported bailiffs by charging arrested poachers, and the SFPA provided one aerial surveillance flight of the Moray Firth annually in July during the peak salmon and sea trout runs. Fishery owners funded bailiffs’ anti-poaching activities through the annual levies raised by DSFBs under the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act (2003) to protect salmon and sea trout stocks. In 2003 and 2004 SNH also provided funding for DSFB coastal boat patrols. While there had been prior collaboration between some neighbouring DSFBs in the Inner Moray Firth, under OFN all bailiffs collaborated throughout the region to jointly patrol and share information across all 12 DSFBs’ jurisdictional boundaries.

In 1992 the Scottish Agricultural College’s Veterinary Services Division established a monitoring program for stranded marine mammals. Carcasses reported by the public are retrieved from around the Scottish coast, and the college performs post mortems to diagnose the cause of death. As part of OFN, the local community and tourists reported stranded dolphins in the Moray Firth to the college, who monitored for fatalities caused by gill nets, and provided data to SNH.

OFN was launched in June 2002 with a media event at a popular dolphin-viewing location in the SAC. Posters and leaflets were published and distributed to tour operators and at coastal amenity sites (e.g. beach car parks, scenic viewpoints, visitor centres) highlighting the potential impact of illegal gill nets on dolphins, providing information on how to distinguish them from commercial salmon nets, and the free-phone number. This publicity exercise was repeated annually.

Evaluating the impact of OFN

Because DSFBs only began systematically recording net retrieval data in 2002 as part of OFN it was not possible to measure OFN’s impact on poaching effort by comparing annual net interceptions before and after the scheme’s introduction. It was also not feasible to interview poachers about the scheme’s effect on their behaviour. Based on available data, we instead tested the following propositions regarding the effectiveness of OFN:

Proposition 1: Dolphin by-catch risk declined after the introduction of OFN: We analysed the features of by-catch risk before and after OFN’s implementation using Harwood’s (1999) framework developed to assess by-catch risks for small cetaceans in off-shore North Sea fisheries. This involves two stages: the identification of by-catch hazard, and an assessment of by-catch exposure, which when combined provide a risk characterisation.

A. By-catch hazard: Scottish Agricultural College data on dolphin fatalities in the Moray Firth were collated and analysed for direct anthropogenic causes including by-catch in gill nets before (1992-2001) and after (2002-2008) OFN’s implementation.

B. By-catch exposure: By-catch exposure is greatest where high fishing effort and cetacean densities coincide in time and space [46]. We examined this relationship by combining data on the temporal and spatial distribution of illegal gill nets (as a surrogate for poaching effort), salmon and sea trout (as the resource targeted by poachers) and dolphins:

I. Illegal gill nets: DSFB coastal patrols are undertaken between April and October, when most salmon and sea trout runs reach the coast and ascend rivers [41]. Data on the dimensions, locations and months of retrieved nets were collated for 2002- 2008. Net locations were recorded by bailiffs to an accuracy of 500m, and mapped using a Geographical Information System (ESRI ArcGIS9.2). Levels of surveillance were reported by all DSFBs to be consistent between years and months in 2002-2008. It was not possible to measure tourist or community surveillance effort, and we assumed this was also consistent between years.

II. Salmon and sea trout: To assess the temporal abundance of salmon and sea trout (henceforth ‘salmonids’) we calculated catch per unit effort (annual or mean monthly total salmonid catch per net fished) in 2002-2008 for the five active commercial stake netting stations (Figure 1), which fished in April-August annually. Although sweep nets were also active they only fished in June-August, and differences in gear type and hence units of effort prevented the aggregation of catch and effort data with stake nets.

III. Dolphins: No data are available for the temporal occurrence of dolphins in 2002-2008, but in the 1990s Wilson et al. [37] recorded peak sightings in May-August in the Inner Moray Firth. Based on early studies of the dolphin population, the Inner Moray Firth SAC was delineated in 1995 (Figure 1). Since the designation more information on the population’s range became available, showing that they also utilise other areas of the Moray Firth and the Scottish east coast [38]. Within the Moray Firth Wilson et al. [47] identified an area of regular sightings which includes 70% of the SAC but also extends along the southern coast of the Outer Moray Firth (Figure 1), which we refer to as the dolphins’ ‘core range’.

Proposition 2: Annual poaching effort declined independently of salmonid abundance: Based on the positive correlation between monthly net interceptions and salmonid abundance in 2002-2008 (see Results) we predicted that annual poaching effort would also be positively correlated with annual salmonid abundance. Hence we hypothesised that OFN’s impact on poaching effort would be demonstrated by a decline in annual net interceptions that was independent of annual salmonid abundance.

Proposition 3: Public surveillance contributed substantially to net and poacher interceptions: We predicted that with the increased level of surveillance provided by tourists and local communities introduced by OFN, the proportion of nets and poachers intercepted by statutory authorities as a result of reports from the free-phone service would be substantial. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the total numbers of nets intercepted and poachers arrested in 2002-2008 as a result of free-phone reports with those apprehended independently by DSFB bailiffs and police through routine surveillance.

Data analysis

For the analysis of by-catch risk, temporal relationships between the annual and monthly occurrence of illegal nets and salmonid abundance were assessed using Pearson’s rank correlations. The relative spatial occurrence of illegal gill nets was compared between coastline within (192km) and outside the Inner Moray Firth SAC (331km), and between coastline within (230km) and outside the dolphins’ core range (293km) using x2 contingency tables. We also compared the proportion of total nets intercepted due to public reports with those intercepted independently by statutory authorities using x2 contingency tables.

Results

Proposition 1: Dolphin by-catch risk declined after the introduction of OFN

A. By-catch hazard: In 1992-2008 a total of 39 dolphin fatalities were reported and examined in the Moray Firth. Cause of death was diagnosed for 18 (46%), of which two (11%) were found entangled and drowned in illegal salmon gill nets, in May 1996 and July 1999 (Table 1). They were both located in the dolphin core range at Findochty, one of five locations of concentrated poaching activity in 2002-2008 (see below). Of the diagnosed cases, these were the only ones caused directly by anthropogenic factors. Cause of death could not be determined for the remaining 21 (54%) of fatalities due to the advanced state of decomposition of carcasses. In 2002-2008 nine dolphin carcasses were retrieved from the Moray Firth. Cause of death was diagnosed for one, which was due to a chronic bacterial infection (Table 1); diagnosis of the remaining eight was impossible due to carcass decomposition (Table 2). Of these, seven occurred in June, July or August.

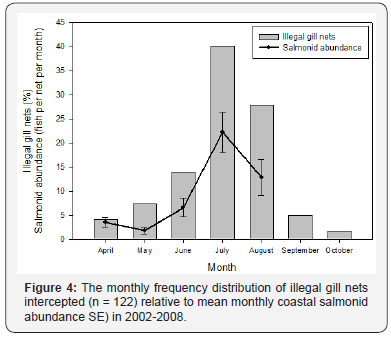

B. By-catch exposure: In total 122 nets were intercepted in 2002-2008. Numbers declined from 31 in 2002 to 8 in 2008, an overall decrease of 74% (Figure 3). Nets were retrieved in April-October, with a peak of 40% occurring in July. Mean monthly salmonid abundance also peaked in July, and there was a statistically significant and positive correlation with net occurrence in April-August (r = 0.98, p < 0.005, n = 5; Figure 4).

All nets were manufactured from clear mono- or multifilament nylon and were set within 1km of the shore to fish statically from the water’s surface. Forty-eight were measured, and had a mean length (±SE) of 48.3m (±3.0, range 20.0-137.0), depth of 3.7m (±0.1, range 1.8-5.5) and mesh size of 11.2cm (±2.0, range 7.5-25.0).

Nets were intercepted at 35 locations (Figure 5). However, 45 (37%) were found at only five (14%) of the locations, the villages of Findochty, Burghead, Munlochy Bay, Avoch and Brora. Four of these were within the SAC, and four within the core range. Seventy-three nets (60%) were retrieved within the SAC and 49 outside, a statistically significant difference relative to the coastline length (x2 =21.86, df = 1, p<0.001). Eighty-three (68%) were found within the dolphins’ core range and 39 outside, a significant difference (x2 =22.92, df = 1, p<0.001).

Proposition 2: Annual poaching effort declined independently of salmonid abundance

There was no statistically significant correlation between the declining trend in annual net interceptions in 2002-2008 and annual salmonid abundance (r = -0.36, p = 0.43, n = 7), which fluctuated over the same period (Figure 3).

Proposition 3: Public surveillance contributed substantially to net and poacher interceptions

Of the 122 nets intercepted, six (5%) were reported via the free-phone service and retrieved by bailiffs. The remaining 116 (95%) were intercepted independently by bailiffs, a statistically significant difference (x2 =72.69, df =1, p<0.001). Three poachers were arrested by bailiffs in the Inner Moray Firth in September 2003, August 2004 and July 2007 and charged by the Highland Constabulary. All were residents of the Inner Morey Firth area. They were convicted by the Inverness District Court under the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act (2003), and fined ₤100, ₤175 and ₤225, respectively, and their nets confiscated. No arrests resulted from information provided through the free-phone service. However, the third poacher had previously been arrested in August 2006 by bailiffs when he was sighted fishing and reported via the free-phone service, but the charges were dropped by the Inverness District Court due to insufficient evidence.

Discussion

In spite of limited data which restricted a more comprehensive analysis, there was some circumstantial evidence that OFN was effective in suppressing poaching effort. As indicated by illegal gill net interceptions, poaching activity appeared to decline considerably by 74% from 2002-2008, and with it by-catch risk, as corroborated by no further confirmed cases of dolphin bycatch. As a consequence, the SAC management plan’s original assessment that the likelihood of by-catch was ‘moderate’ [44] could be redefined as ‘minimal’.

While by-catch risk receded, dolphins were still exposed to illegal gill nets. Temporally, exposure was greatest in July when poaching effort peaked in response to salmonid abundance, followed by August, June and May. Spatially, exposure was significantly greater within the SAC and the core range than along neighbouring coasts. Exposure was not spatially homogenous within the SAC and core range, however, with the five locations of Findochty, Burghead, Munlochy Bay, Avoch and Brora appearing to be centres of poaching activity. These patterns of temporal and spatial risk are corroborated by the known cases of dolphin mortalities in 1996 and 1999, which occurred in May and July within the population’s core range at the village of Findochty. Hence the risk of by-catch should remain a priority for the SAC management plan, particularly since illegal salmon gill nets were the only direct anthropogenic cause of fatalities diagnosed by the Scottish Agricultural College in 1992-2008

This risk is exacerbated by the predation of adult salmonids by dolphins in the Moray Firth [48,49]. Dolphins congregate around confined coastal channels in the Inner Moray Firth, and also along the southern Outer Moray Firth coast to intercept migrating shoals during the summer months [50-53], often within 1km of the shore [37,54,55] where all gill nets were intercepted. Hence, in the summer months dolphins and poachers appear to target the same aggregations of salmon and sea trout in similar locations. As for other examples of gill net impacts on small cetaceans [5,6,9,46], it is this coincidence of high cetacean densities and intensive fishing effort in time and space which is generating by-catch risk in the Moray Firth.

DSFB bailiffs reported consistent effort between years and months, and hence the net retrieval data are likely to be a representative index for both annual and monthly patterns in poaching effort and by-catch risk. However, it is possible that the results were distorted by geographical variations in surveillance effort. Bailiffs with jurisdictions within the Inner Moray Firth may have patrolled more regularly and efficiently than those along the Outer Moray Firth coast due to more sheltered sea conditions, increasing the likelihood of net encounters and hence biasing our estimates of spatial by-catch exposure towards the SAC and dolphins’ core range. Similarly, tour operators focus their activity in the Inner Moray Firth and the dolphin’s core range where dolphin sightings are most likely (author’s unpublished data), but since only 5% of net interceptions were derived from reports by the public, this is unlikely to have had a major influence on our results.

DSFB bailiffs reported consistent effort between years and months, and hence the net retrieval data are likely to be a representative index for both annual and monthly patterns in poaching effort and by-catch risk. However, it is possible that the results were distorted by geographical variations in surveillance effort. Bailiffs with jurisdictions within the Inner Moray Firth may have patrolled more regularly and efficiently than those along the Outer Moray Firth coast due to more sheltered sea conditions, increasing the likelihood of net encounters and hence biasing our estimates of spatial by-catch exposure towards the SAC and dolphins’ core range. Similarly, tour operators focus their activity in the Inner Moray Firth and the dolphin’s core range where dolphin sightings are most likely (author’s unpublished data), but since only 5% of net interceptions were derived from reports by the public, this is unlikely to have had a major influence on our results.

While OFN may have reduced by-catch risk, this was not clearly demonstrated by the Scottish Agricultural College’s stranding data. For the nine carcasses retrieved since June 2002, cause of death could only be established for one, and this was not due to entanglement in fishing nets. It is feasible that some of the undiagnosed fatalities were caused by illegal gill net by-catch, since seven occurred in the months of June-August when by-catch exposure was highest. As well as the difficulty of diagnosing cause of death due to carcass decomposition, utilising carcass retrieval information to monitor the impact of OFN is problematic because poachers may dispose of dolphins found entangled to avoid prosecution under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. This factor may have also have resulted in an underestimate of dolphin fatalities prior to 2002, and hence the SAC management plan’s initial assessment of the threat posed by gill nets. Hence annual gill net retrieval rates, rather than dolphin fatalities, may be the most representative and practical method for evaluating the efficacy of OFN or similar schemes.

It is not clear how OFN contributed to the decline in poaching effort. Relative to the situation prior to 2002, the primary change induced by OFN has been increased collaboration between stakeholders, and the mobilisation of additional surveillance effort through the involvement of tourists, tour operators and communities. Yet only 5% of nets were intercepted as a result of reports from the public, and none of the three convictions of poachers resulted from these, although one was previously arrested due to a community report. An alternative explanation is that OFN had an indirect effect by creating a deterrent to poaching. Common-pool resource theory proposes that an important pre-requisite for effective CBNRM is the monitoring of rule compliance by community members, which internalises social sanctions and promotes cooperative behaviour, and this is enhanced by the employment of guards such as bailiffs [29].

Other factors unrelated to OFN may also be involved. Criminology suggests that illegitimate behaviour is driven by trade-offs between the benefits of illegal activity relative to legal opportunities [58]. In communities bordering African protected areas, wildlife poaching is negatively correlated with sources of income from other available livelihood strategies [59,16]. While the livelihood profiles of Moray Firth poachers are not known, it is feasible that the emergence of alternative economic opportunities have reduced the incentive to fish illegally. Linked to this is the likelihood that the black market for wild salmon has been undercut by the growing availability of farmed salmon. Since its establishment in the 1980s, by 2002 Scottish salmon aquaculture production had increased to more than 120 000 tonnes per annum [60], potentially providing a cheaper substitute for wild salmon. The flooding of markets with captivebred wildlife products is a well-established strategy for reducing the incentive to poach [61].

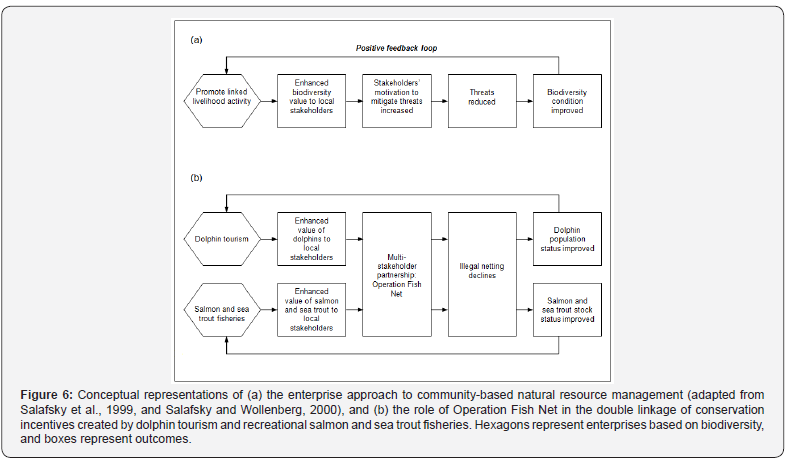

The apparent success of OFN may also be attributable to its manifestations of the enterprise approach to CBNRM. Generating livelihoods from threatened species or habitats can create a positive feedback loop between livelihoods and conservation [20,21] (Figure 6a). In the Moray Firth, the recent establishment of a dolphin tourism industry has generated an added incentive for their protection beyond their intrinsic biodiversity value. OFN is also strengthened by the additional linkage to the protection of salmonid stocks. Recreational salmon and sea trout fisheries are of even greater value to the local economy than marine wildlife tourism [41]. This awareness may therefore have created an added incentive for local fishery owners to fund DSFB coastal patrols, and community support for surveillance. Hence OFN demonstrates a double linkage between the utilisation and conservation of dolphins, salmon and sea trout (Figure 6b). With the emergence of these linkages through the growth of Moray Firth tourism, poaching may have become an activity directly juxtaposed to contemporary community interests.

OFN also exhibits a network of information-sharing and resourcing linking statutory and non-statutory stakeholders in dolphin and salmonid management across the local (catchment), regional (Moray Firth) and national scales (Figure 2), which are characteristic features of adaptive co-management [32-34]. This governance network is mirrored by the Moray Firth Seal Management Plan, an initiative established in 2005 by several of the OFN stakeholders to manage conflict between harbour (Phoca vitulina) and grey (Halichoerus grypus) seal conservation, tourism and salmon fisheries [36,41,62-65]. Both initiatives have benefitted from an enabling environment provided by SNH and the Scottish Government which has encouraged informal and nested institutions to develop autonomously, supported by appropriate coordination and resourcing, such as training of DSFB bailiffs in seal management [42] and funding for DSFB boat patrols. The adoption of such an enabling role by government is another important design principle for effective CBNRM [29], and is a central to the formation of stakeholder partnerships required to implement SACs [65].

Conclusion

In the terms of the 2001 Inner Moray Firth SAC management plan, our results indicate that the likelihood of dolphin by-catch receded from ‘moderate’ in 2002-2008, but the consequences remain ‘severe’ for the small population. Hence surveillance should be maintained, and effort should be targeted in June- August where the dolphins’ core coastal range overlaps the remaining locations of concentrated poaching activity.

Evaluating the impact of CBNRM is notoriously problematic due to the coincidental occurrence of multiple factors which also influence outcomes [13,20,66,67]. This is also evident for OFN, where it was impossible to isolate the scheme’s impact from other possible influences on poachers’ behaviour. Evaluating OFN’s impacts was also constrained by the lack of net retrieval data prior to the scheme’s inception, the difficulty of surveying poachers, and the limitations of using dolphin fatalities as an indicator of success. All of these issues are likely to be inherent in the evaluation of CBNRM schemes which aim to mitigate illegal by-catch of marine mammals [68-70].

Nonetheless, it is probable that OFN at least partially contributed to the observed decline in poaching effort. This may be attributable to the fact that OFN exhibits several characteristics of effective CBNRM, including the enterprise approach and a cross scale and multi-stakeholder governance network, and these may also be pre-requisites for the success of other schemes. However, principles of adaptive co-management suggest that the longevity of the scheme could be enhanced by the deliberate introduction of a learning forum to maintain and promote social networks, information sharing and adaptive learning. As such, OFN provides useful insights for the establishment and evaluation of similar community-based strategies to protect coastal or freshwater cetaceans from illegal or unregulated fisheries.

Acknowledgement

This research was made possible by the cooperation of the Caithness, Helmsdale, Brora, Beauly, Ness, Nairn, Findhorn, Lossie and Deveron DSFBs. Jackie Anderson (Marine Scotland) provided netting stations catch data. Patrols by the Spey, Conon, Ness and Kyle of Sutherland DSFBs were supported by a Scottish Natural Heritage grant (GRA APP/6317) in 2003 and 2004 as part of OFN. Marine Scotland and DEFRA provides funding for the Scottish Agricultural College to monitor cetacean strandings. Tim Skewes and Caroline Bruce provided cartographic skills.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have economic interests or any other conflict of interests in the publication of this study.

References

- Lewison RL, Crowder LB, Read AJ, Freeman SA (2004) Understanding impacts of fisheries bycatch on marine megafauna. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 19(11): 598-604.

- Marsh H, Arnold P, Freeman M, Haynes D, Laist D, et al. (2003) Strategies for conserving marine mammals. In: Gates N, Hindell M, Kirkwood R (Eds.), Marine Mammals: Fisheries, Tourism and Management Issues, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia, pp. 1-19.

- Slooten E, Fletcher D, Taylor BL (2000) Accounting for uncertainty in risk assessment: case study of Hector’s dolphin mortality due to gillnet entanglement. Conservation Biology 14(5): 1264-1270.

- Dawson SM, Slooten E, Pichler F, Russell K, Baker CS (2001) North Island Hector’s dolphins are threatened with extinction. Marine Mammal Science 17: 366-371.

- Kreb D, Budiono (2005) Conservation management of small core areas: key to survival of the critically endangered population of Irrawaddy river dolphins Orcaella brevirostris in Indonesia. Oryx 39(2): 1-11.

- Martin AR, da Silva VMF, Salmon DL (2004) Riverine habitat preferences of botos (Inia geoffrensis) and tucuxis (Sotalia fluviatilis) in the central Amazon. Marine Mammal Science 20(2): 189-200.

- Hammond PS, Bergen H, Benke H, Borchers DL, Collet A, et al. (2002) Abundance of harbour porpoise and other cetaceans in the North Sea and adjacent waters. Journal of Applied Ecology 39(2): 361-376

- Byrd BL, Hohn FH, Munden FH (2008) Effects of commercial fishing regulations on stranding rates of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncates). Fishery Bulletin 106(1): 72-81.

- Iñíguez MA, Hevia M, Gasparrou C, Tomsin AL, Secchi E (2003) Preliminary estimate of incidental mortality of Commerson’s dolphins (Cephalorhynchus commersonii) in an artisanal setnet fishery in La Angelina Beach and Ria Gallegos, Santa Cruz, Argentina. LAJAM 2(2): 87-94.

- Grech A, Marsh H, Coles R (2008) A spatial assessment of the risk to a mobile marine mammal from by catch. Aquatic Conservation: Marine Fresh water Ecosystems 18: 1127-1139.

- Gunn R, Hardesty BD, Butler JRA (2010) Tackling ‘ghost nets’: local solutions to a global issue in northern Australia. Ecological Management and Restoration 11(2): 88-98.

- Butler JRA, Gunn R, Berry H, Wagey GA, Hardesty BD, et al. (2013) A Value Chain Analysis of ghost nets in the Arafura Sea: identifying transboundary stakeholders, intervention points and livelihood trade-offs. J Environ Manage 123: 14-25.

- Berkes F (2004) Rethinking community-based conservation. Conservation Biology 18(3): 621-630

- Berkes F (2007) Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(39): 15188-15193.

- Gautam AP, Shivakoti GP (2005) Conditions for successful collective action in forestry: some evidence from the hills of Nepal. Society and Natural Resources 18: 153-171

- Johannesen AB (2005) Wildlife conservation policies and incentives to hunt: an empirical analysis of illegal hunting in western Serengeti, Tanzania. Environment and Development Economics 10(3): 271-292.

- Ndibalema VG, Songorwa AN (2007) Illegal meat hunting in Serengeti: dynamics in consumption and preferences. African Journal of Ecology 46(3): 311-319.

- Pomeroy R (2007) Conditions for successful fisheries and coastal resources co-management: lessons learned in Asia, Africa and the wider Caribbean. In: Armitage D, Berkes F, Doubleday N (Eds.), Adaptive Co-management: Collaboration, Learning and Multi-level Governance, UBC Press, Vancouver, Toronto, Canada, pp. 172-190.

- Pinkerton E (2010) Coastal marine systems: conserving fish and sustaining community livelihoods with co-management. In: Chapin FS, Kofinas GP, Folke C (Eds.), Principles of Ecosystem Stewardship: Resilience-based Natural Resource Management in a Changing World, Springer Science+Business Media, New York, USA, pp. 241-257.

- Salafsky N, Cordes B, Parks J, Hochman C (1999) Evaluating linkages between business, the environment and local communities: final analytical results from the Biodiversity Conservation Network. Biodiversity Support Program, Washington, DC, USA.

- Salafsky N, Wollenberg E (2000) Linking livelihoods and conservation: a conceptual framework and scale for assessing the integration of human needs and biodiversity. World Development 28(8): 1421-1438

- Butler JRA (1994) Cape clawless otter conservation and catchment management in Zimbabwe: a case study. Oryx 28(4): 276-282.

- Butler JRA, du Toit JT (1994) Diet and conservation status of Cape clawless otters in eastern Zimbabwe. S Afr J Wildl Res 24: 41-47.

- Campbell BM, Butler JRA, Mapaure I, Vermeulen SJ, Mashove P (1996) Elephant damage and safari hunting in Pterocarpus angolensis woodland in north-western Matabeleland, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Ecology 34: 380-388.

- Mvula AC (2001) Fair trade in tourism to protected areas – a micro case study of wildlife tourism to South Luangwa National Park, Zambia. International Journal of Tourism Research 3(5): 393-405.

- Lepp A (2002) Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park: meeting the challenges of conservation and community development through sustainable tourism. In: Johnston B (Ed.), Life and Death Matters: Human Rights and the Environment at the End of the Millennium, Sage, London, p. 211-220.

- Nilsson D, Gramotnev G, Baxter G, Butler JRA, Wich SA, et al. (2016) Community motivations to engage in conservation behavior to conserve the Sumatran orangutan. Conserv Biol 30(4): 816-826.

- Nilsson D, Baxter G, Butler JRA, Wich SA, McAlpine CA (2016) How do community-based conservation programs in developing countries change human behaviour? A realist synthesis. Biological Conservation 200: 93-103.

- Cox M, Arnold G, Tomas SV (2010) A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecology and Society 15(4): 38.

- Ostrom E (2007) A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(39): 15181-15187.

- Ostrom E (2008) The challenge of common-pool resources. Environment, Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 50(4): 8-21.

- Plummer R, Armitage DR (2007) Charting the new territory of adaptive co-management: a Delphi study. Ecology and Society 12(2): 10.

- Armitage D, Plummer R, Berkes F, Arthur R, Charles AT, et al. (2009) Adaptive co-management for social-ecological complexity. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7(2): 95-102.

- Plummer R (2009) The adaptive co-management process: an initial synthesis of representative models and influential variables. Ecology and Society 14(2): 24.

- Butler JRA, Middlemas SJ, Graham IM, Harris RN (2011) Perceptions and costs of seal impacts on salmon and sea trout fisheries in the Moray Firth, Scotland: implications for the adaptive co-management of Special Areas of Conservation. Marine Policy 35: 317-323.

- Butler JRA, Young JC, McMyn I, Leyshon B, Graham IM, et al. (2015) Evaluating adaptive co-management as conservation conflict resolution: learning from seals and salmon. J Environ Manage 160: 212-225.

- Wilson B, Thompson PM, Hammond PS (1997) Habitat use by bottlenose dolphins: seasonal distribution and stratified movement patterns in the Moray Firth, Scotland. Journal of Applied Ecology 34(6): 1365-1374

- Thompson PM, Cheney B, Ingram S (2011) In: Thompson PM, Cheney B, Ingram S (Eds.), Distribution, abundance and population structure of bottlenose dolphins in Scottish waters. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 354, Battleby, Perth, UK.

- Scottish Natural Heritage (1995) Natura 2000: a guide to the 1992 EC Habitats Directive in Scotland’s marine environment. Scottish Natural Heritage, Battleby, Perth, UK.

- Hoyt E (2001) Whale-watching 2001: worldwide tourism numbers, expenditures, and expanding socioeconomic benefits. International Fund for Animal Welfare, Crowborough, England.

- Butler JRA, Middlemas SJ, McKelvey SA, McMyn I, Leyshon B, et al. (2008) The Moray Firth Seal Management Plan: an adaptive framework for balancing the conservation of seals, salmon, fisheries and wildlife tourism in the UK. Aquatic Conservation: Marine Fresh water Ecosystems 18: 1025-1038.

- Butler JRA, Radford A, Riddington G, Laughton RL (2009) Evaluating an ecosystem service provided by Atlantic salmon, sea trout and other fish species in the River Spey, Scotland: the economic impact of recreational rod fisheries. Fisheries Research 96: 259-266.

- Williamson R (2004) Powers of water bailiffs and wardens to enforce the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Acts. Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department, Edinburgh, UK.

- Moray Firth Partnership (2001) The Moray Firth candidate Special Area of Conservation management scheme. The Moray Firth Partnership, Inverness, UK.

- Sanders-Reed CA, Hammond PS, Grellier K, Thompson PM (1999) Development of a population model for bottlenose dolphins. Scottish Natural Heritage Research Survey and Monitoring Report No. 156, Scottish Natural Heritage, Battleby, Perth, UK.

- Harwood J (1999) A risk assessment framework for the reduction of cetacean by-catches. Aquatic Conservation: Marine Fresh water Ecosystems 9: 593-599.

- Wilson B, Hammond PS, Thompson PM (1999) Estimating size and assessing trends in a coastal bottlenose dolphin population. Ecological Applications 9(1): 288-300.

- Thompson PM, MacKay F (1999) Pattern and prevalence of predator damage on adult Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., returning to a river system in north-east Scotland. Fisheries Management and Ecology 6(4): 335-343.

- Santos MB, Pierce GJ, Reid RJ, Patterson IAP, Ross HM, et al. (2001) Stomach contents of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Scottish waters. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 81(5): 873-878.

- Janik VM (2000) Food-related bray calls in wild bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Proc Biol Sci 267(1446): 923-927.

- Hastie GD, Barton TR, Grellier K, Hammond PS, Swift RJ, et al. (2003) Distribution of small cetaceans within a candidate Special Area of Conservation; implications for management. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 5: 261-266.

- Hastie GD, Wilson B, Thompson PM (2003) Fine-scale habitat selection by coastal bottlenose dolphins: application of a new land-based videomontage technique. Canadian Journal of Zoology 81(3): 469-478.

- Lusseau D, Williams R, Wilson B, Grellier K, Barton TR, et al. (2004) Parallel influence of climate on the behaviour of Pacific killer whales and Atlantic bottlenose dolphins. Ecology Letters 7(11): 1068-1076

- Mendes S, Turrell W, Lutkebohle T, Paul Thompson (2002) Influence of tidal cycle and a tidal intrusion front on the spatio-temporal distribution of coastal bottlenose dolphins. Marine Ecology Progress Series 239: 221-229.

- Thompson PM, White S, Dickson E (2004) Co-variation in the probabilities of sighting harbour porpoises and bottlenose dolphins. Marine Mammal Science 20(2): 322-328.

- Forsyth CJ, Gramling R, Wooddell G (1998) The game of poaching: folk crimes in southwest Louisiana. Society and Natural Resources 11: 25- 38.

- McSkimming MJ, Berg BL (2008) Motivations for citizen involvement in a community crime prevention initiative: Pennsylvania’s TIP (Turn in a Poacher) Program. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 13(4): 234-242.

- Ehrlich I (1973) Participation in illegitimate activities: a theoretical and empirical investigation. The Journal of Political Economy 81(3): 521-565.

- Barrett CB, Arcese P (1998) Wildlife harvest in integrated conservation and development projects: linking harvest to household demand, agricultural production, and environmental shocks in the Serengeti. Land Economics 74(4): 449-465.

- Butler JRA (2002) Wild salmonids and sea lice infestations on the west coast of Scotland: sources of infection and implications for the management of marine salmon farms. Pest Manag Sci 58(6): 595-608.

- Damania R, Bulte EH (2007) The economics of wildlife farming and endangered species conservation. Ecological Economics 62(3-4): 461- 472.

- Butler JRA, Middlemas SJ, Graham IM, Thompson PM, Armstrong JD (2006) Modelling the impacts of removing seal predation from Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., rivers in Scotland: a tool for targeting conflict resolution. Fisheries Management and Ecology 13: 285-291.

- Thompson PM, Mackey B, Barton TM, Duck C, Butler JRA (2007) Assessing the potential impact of salmon fisheries management on the conservation status of harbour seals in (Phoca vitulina) NE Scotland. Animal Conservation 10(1): 48-56.

- Butler JRA (2011) The challenge of knowledge integration in the adaptive co-management of conflicting ecosystem services provided by seals and salmon. Animal Conservation 14: 599-601.

- Young JC, Butler JRA, Jordan A, Watt AD (2012) Less government intervention in biodiversity management: risks and opportunities in the UK. Biodiversity and Conservation Biodiversity and Conservation 21(4): 1095-1100.

- Agrawal A, Redford K (2006) Poverty, development and biodiversity conservation: shooting in the dark? Wildlife Conservation Society, New York, USA.

- Tallis H, Kareiva P, Marvier M, Chang A (2008) An ecosystem services framework to support both practical conservation and economic development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 105(28): 9457-9464.

- Armitage D (2005) Adaptive capacity and community-based natural resource management. Environ Manage 35(6): 703-715.

- Hastie GD, Wilson B, Wilson LJ, Parsons KM, Thompson PM (2004) Functional mechanisms underlying cetacean distribution patterns: hotspots for bottlenose dolphins are linked to foraging. Marine Biology 144(2): 397-403.

- Johannesen AB, Skonhoft A (2005) Tourism, poaching and wildlife conservation: what can integrated conservation and development projects accomplish? Resource and Energy Economics 27: 208-226.