Postural Control in Patients with Respiratory Dysfunctions: A Systematic Review

Guilherme Medeiros de Alvarenga1,2, Débora Botega Fernandes1, Fabrício Gabriel Bora1, Giulia Weigel Rebonato1, Yuki Moitinho Sogo1, Vinicius Coneglian Santos1, Júlio Cesar Francisco1* and Humberto Remigio Gamba2

1Department of Physiotherapy, Universidade Positivo, UP, Brazil

2Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, CPGEI, Brazil

Submission: April 20, 2018; Published: May 03, 2018

*Corresponding author: Júlio Cesar Francisco Department of Physiotherapy, Universidade Positivo, UP, Brazil.

How to cite this article: Guilherme Medeiros de Alvarenga, Débora Botega Fernandes, Fabrício Gabriel Bora, Júlio Cesar Francisco, et al. Postural Control in Patients with Respiratory Dysfunctions: A Systematic Review. OAJ Gerontol & Geriatric Med. 2018; 4(2): 555632. DOI: 10.19080/OAJGGM.2018.04.555632

Abstract

Objective:To identify the main methods of intervention by means of exercises through postural control for COPD and asthmatic patients and their beneficial effects.

Methods:A systematic review was performed to identify which postural control treatment should be applied in these cases. The following bibliographic databases were consulted: PubMed, Bireme and Science Direct. Clinical trials involving techniques for postural control and that compared the results analyzed in the pre and post intervention period.

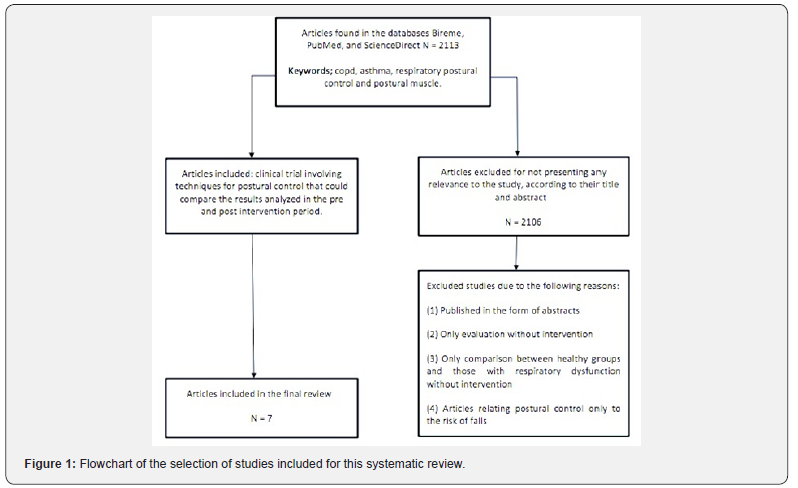

Result: The electronic search yielded a total of 2113 references published in any language, of which only 7 met the criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

Conclusion:Broadly, the age bracket above 50 years was observed in 6 out of the 7 studies; resistance training in 3 out of 7 studies; vibratory platform training in 1out of 7 studies; postural control training associated with breathing in 3 out of 7 studies and clinically significant improvement in intervention in 3 out of 7 studies, demonstrating a variety of treatment techniques making it difficult to produce a higher level of evidence.

Keywords: COPD; Respiratory; Asthma; Postural Muscle; Postural Control

Abbrevations: COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; WHO: World Health Organization; COLD: Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; UN: United Nations; ABC: Activities Specific Balance Confidence scale; TUG: Time Up and Go; BBS: Berg Balance Scale; SGRQ: St George’s respiratory questionnaire; RS: Romberg stance ; STEC: SemiTandem Stance ; STEO: Semi Tandem Stance; OLS: One Led Stance; CRQ: Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; TOC: Oxygen Cost Diagram; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; MVV: Minute Volume ; FVC: Forced Vital Capacity; 6MWT: 6-Minute Walk Test

Introduction

Respiratory dysfunctions affect a large part of the world’s population. Among them, two have a prominence and are studied by the World Health Organization (WHO) and by researchers in much of the world. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (COLD), may be defined as a preventable and treatable disease [1]. The COPD is a progressive lung disease and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Canada [2]. It is also identified as one of the leading causes of death in the world. Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (UN) estimate 3 million deaths / year. The Canadian health care system estimates an annual average spending of $1.5 billion [3]. The second dysfunction is asthma. The WHO estimates that 235 million people currently suffer from asthma. Asthma is the most common non communicable disease among children [4]. Today, the impairment in patients with pulmonary diseases goes beyond respiratory changes, delivering many other extra pulmonary consequences [5], as is the case with postural control. The systematic review on postural control in COPD, with studies involving the vast majority of control groups [6] concluded that COPD patients have postural control deficits when compared to healthy groups with combined ages. It is known that intervention in respiratory dysfunctions is aimed at reducing pulmonary disturbances, but especially the extra pulmonary disorders. Considering the spine, thoracic cavity and large muscle groups as fundamental to control the sensation of dyspnea, reducing ventilatory work, intervention improves pulmonary volumes and capacities, postural control and minimizes the effects of disuse with the progression of these diseases [7]. But what would be the best intervention methodology? Thus, this systematically review focuses on the literature concerning to identify the main methods of intervention of the last 7 years, with the use of postural control for COPD and asthmatics patients and their beneficial effects.

Materials and Methods

In the present study, a survey was performed on the PubMed, Bireme and ScienceDirect databases. Studies were selected after defining the DeCS and MeSH search terms, such as asthma, postural control, COPD, postural muscles, respiratory. These terms were crossed via Boolean switch statements (AND), as shown in the following topics:

a) Respiratory and postural control and postural muscle;

b) COPD and postural control and postural muscle and respiratory;

c) Asthma and postural control and postural muscle and respiratory;

d) COPD and respiratory and postural muscle;

e) Asthma and respiratory and postural muscle,

Including titles published from January 2010 to October 2017. Initially, four reviewers (YS, DB, GW, FB) independently assessed all selected titles (n = 2113), analyzed their abstracts based on inclusion criteria defined for the study: a clinical trial involving techniques for postural control and comparing the results analyzed in the pre- and post-intervention period. From this sample the following articles were excluded: those published in the form of abstracts, those that only evaluated the subjects and did not treat, those that only compared between healthy groups and with respiratory dysfunction without intervention and the articles relating the postural control only with the risk of falls. Duplicate items were also omitted (Figure 1). The full texts of the potentially relevant articles were retrieved for final evaluation, and their reference lists were independently checked again by the same reviewers to identify studies of potential relevance not found in the electronic search.

Result and Discussion

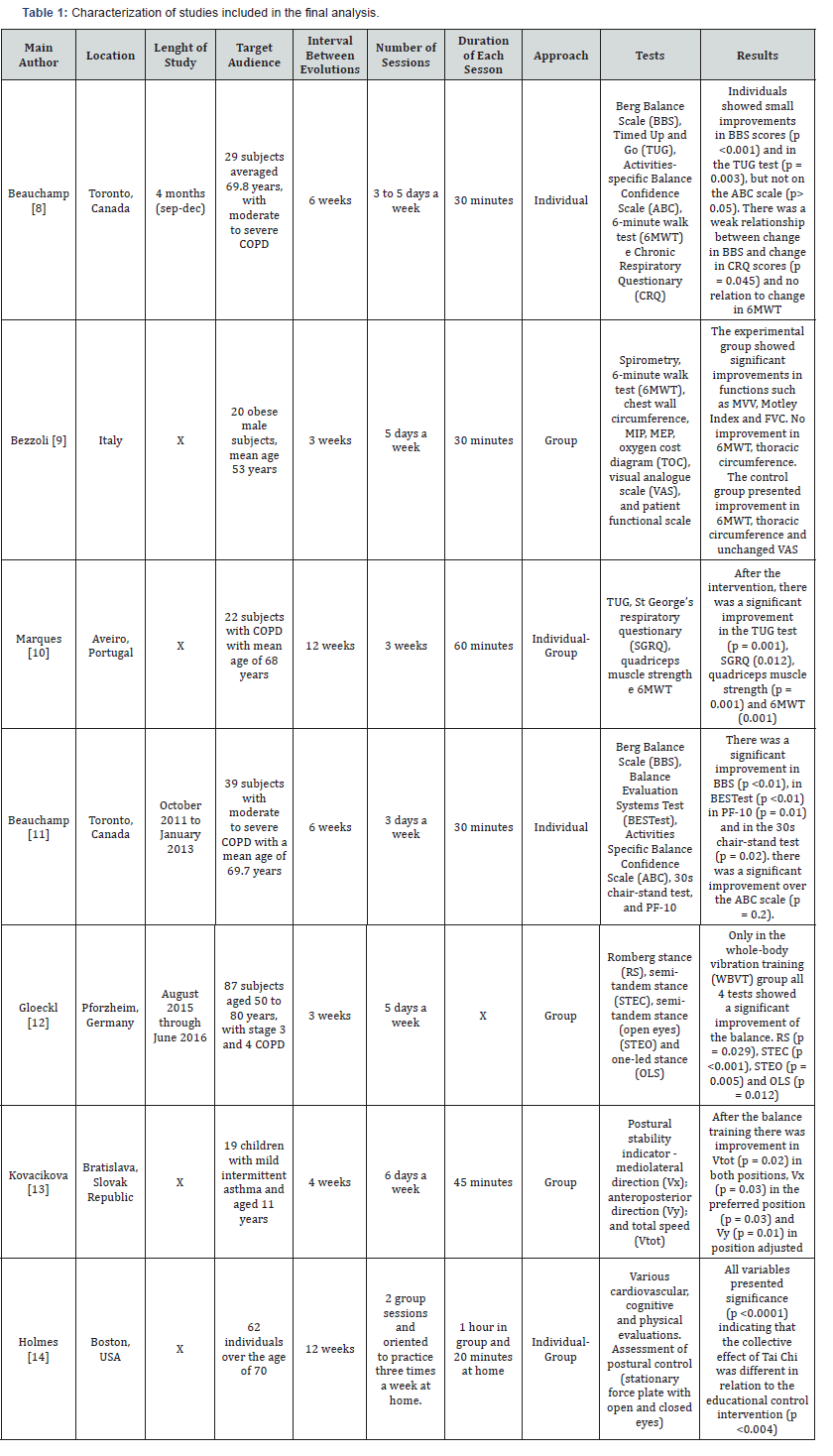

This review provides an important summary of the main available methods of intervention in postural control for patients with COPD and Asthma, indicating the need for more work. Of all the articles included in this review, there are variations of postural control techniques for patients with respiratory dysfunction. Among them are: the time of intervention, in some cases 30-45 min, another 80 min. Such studies ranged from 3 to 12 weeks, 3 to 6 times per week. In addition, some studies have applied gait training; others exercise bike with stipulated speed and other exercise bike with free speed, with low and high intensity of training. Also, resisted exercises with weights or elastic bands, with load defined by 10 RM, free load or by challenges as the intensity supported by the patient, with 10 repetitions or with 15 to 20 repetitions. Traditional exercises or with the use of technological resources such as indicators of postural stability. Balance and coordination exercises. Stretching and relaxation, cognitive tasks. Exercises of diaphragmatic breathing and with closed lips. To finish oriental technique like Tai Chi. This reflects the fragility of the levels of evidence offered by the literature to support these different intervention methodologies (Table 1).

Beauchamp et al. [8], used supervised resistance training in COPD patients 4 to 5 times a week using 6MWT as baseline, each patient received an individualized program of 60% to 80% of the average speed achieved during 6MWT (for treadmill exercise or walking) or 60% to 80% of the VO2max estimate of 6MWT for bicycle training, periods of high intensity exercise were alternated with rest periods (3 min at 80% VO 2 max alternating with 2 min of relative rest). The duration of the exercise progressed until patients could tolerate 20 to 30 minutes of resistance exercise at the most tolerated symptoms level, after which the speed or intensity increased from 10% to 20%. Strength training for upper and lower limbs (3 times per week) included the following lower limb muscles: quadriceps, hamstrings, hip flexors, hip abductors, and hip extensors. The exercises were completed in seated and standing positions with the use of ankle weights for endurance. The training for upper limbs included the muscles, biceps, triceps, pectorals and deltoid using an elastic resistance band. The amount of resistance provided was based on the patient’s ability to complete 15 to 20 replicates [9-11]. Patients received a daily 30-minute class that included stretching in major muscle groups and instructions on diaphragmatic and puckered respiration of the lips. Self-management education and psychological and social support were provided through lectures, relaxation classes and recreational activities at least twice a week for 30 minutes. In a recent study by Gloeckl et al. [12] strength training (15 minutes of cycling at 60% of peak energy) and strength training (four to six exercises on strength training machines with three sets of 15- 20 repetitions for major muscle groups using maximum load. In addition, all patients underwent a supplementary program with squatting exercises on a lateral alternating vibration platform (Galileo®, Novotec Medical GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany) lasting 2 minutes, three Times a week. In general, what varied from one study to the other was: the association between strength and resistance exercises, with association of these elements or chose only to choose strength exercises, in addition, balance exercises were also placed in the intervention program. We used predominantly the following reference tools: ABC (Activities Specific Balance Confidence scale), TUG (TIME UP AND GO), Berg Balance Scale (BBS), St George’s respiratory questionnaire (SGRQ), 6MWT, Romberg stance (RS), semi-tandem stance (STEC), semi-tandem stance (open eyes) (STEO) and one-led stance (OLS). (BESTest), 30-s chair-stand test, PF-10, CRQ (chronic respiratory questionnaire). The ABC scale did not show significant improvement in any of the studies, but the Berg balance scale and the TUG test showed significant improvement in all the studies that used these tests as analysis [12]. In 2016, Bezolli et al. [9] studied participants with obesity, with an age range of around 53 years. An intervention period of 3 weeks was analyzed, with 5 interventions per week, lasting 30 minutes in a group. The intervention was with resistance training using a cycloergometer and specific exercises with the objective of increasing the perception and activation of the lumbarpelvic musculature; world reference evaluative tools such as: Spirometry, 6-minute walk test, chest wall circumference, MIP, MEP, oxygen cost diagram (TOC), visual analogue scale (VAS), and patient functional scale were used.

The experimental group showed significant improvements in functions such as minute volume (MVV), Motley Index and forced vital capacity (FVC). There was no improvement in 6MWT and in the thoracic circumference. The control group presented improvement in 6MWT, thoracic circumference and VAS remained unchanged. The results were beneficial but there is little research on this subject, so it was not possible to compare studies on postural control and improvement of respiratory performance in obese individuals. The study by Marques et al. [10] in COPD patients, applied a warm-up of 5 to 10 minutes, involving range of motion, stretching, low-intensity aerobic exercises and respiratory techniques such as pursed lip breathing, body positions, diaphragmatic breathing, and airways cleaning techniques. After that, resistance training (walking) for 20 minutes with 60% to 80% of the average speed achieved during the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). Strength training (15 minutes) included 7 exercises (2 sets of 10 repetitions) for upper and lower limbs using elastic bands, free weights and ankle weights, and the amount of weight applied was between 50% and 85% of 10 repetitions (10RM). The balance training (5 minutes) mostly comprised static and dynamic exercises using vertical positions and were organized in 4 levels

a) Postures that gradually reduced the support base;

b) Dynamic movements that disturbed the center of gravity;

c) Stress to postural muscle groups; and

d) Dynamic movements while performing a secondary task individually or in groups, with a progressively reduced support base. Finally, 10 minutes rest.

Beauchamps et al. [11] used balance training in four main types of exercise:

a) Posture exercises,

b) Transition exercises,

c) Gait exercises, and

d) Functional strengthening.

When a participant was able to complete a task independently and with little instability, the difficulty level was progressively increased by introducing more challenging conditions (eg, closed eyes, addition of a secondary cognitive task, increase in speed / repetition, or disturbances) Kavocikova et al. [13] analyzed participants with asthma, with an age range of around 11 years. The intervention period was 4 weeks, with 6 per week, lasting 45 minutes in a group. The intervention consisted of: respiratory training with diaphragmatic breathing, pursed lip breathing and thoracic expansion exercises. In addition, children also learned clearance techniques (autogenous drainage and active cycle of breathing techniques), 3 sets of 10 repetitions of each breathing exercise followed by a relaxation of 1 minute pause with controlled breathing. Breathing exercises were also performed in the vertical sitting position in a chair and standing position (bipedal and unipedal conditions) in balance devices (Airex Pad, Soft Gym Overball, Bosi® Balance Trainer PROFI and Original Pezzi® Gymnastik Ball Standard). In physical training: proprioceptive exercises, functional strength exercises (lower limbs, upper limbs and core), hand-eye coordination exercises and resistance training. The evaluation tools were: Postural stability indicator - mediolateral direction (Vx); antero-posterior direction (Vy); and total speed (Vtot). Improvement in Vtot in both positions, Vx in the preferred position and Vy in the adjusted position. After the balance training there was improvement in Vtot in both positions, Vx in the preferred position and Vy in the adjusted position.

Finally, Holmes et al. [14] analyzed participants with a mean age of 70 years in a 12-week intervention period, with 2 interventions per week, lasting 80 minutes in a group, and receiving an instruction DVD of the entire protocol to be performed 20 minutes, 3 times a week at home. The intervention consisted of: warm-up exercises focused on range of motion, incorporating attention and images into movement, increasing awareness of breathing and promoting relaxation of body and mind. Cardiovascular, cognitive, physical and postural control evaluations were performed (stationary force plate with open and closed eyes). The results had a significant effect on all the variables presented, indicating that the collective effect of Tai Chi was different in relation to the educational control intervention. Despite the beneficial results obtained, there was no possibility to compare those with other studies. In this review, we analyzed the effect of postural control on respiratory dysfunctions. We observed that the interventions showed significant improvement, mainly in individuals with asthma and COPD. Regarding the number of studies with interventions, there is still a small amount of articles exploring this topic, many of them not so specific. Generally speaking, this review comprised: age group over 50 years (6 out of 7 studies); resistance training (3 out of 7 studies); vibratory platform training (1 out of 7 studies); postural control training associated with breathing (3 out of 7 studies), and clinically significant improvement in intervention (3 out of 7 studies). Detailing the approach of the clinical trials, we adopted at least one of the evaluation methods below: the Berg Scale (BBS); 6-minute walk test (6MWT) and Time Up Test (TUG); no significant change was found in 6MWT, but with changes in the other tests. The study that presented a larger sample, with the objective of verifying the capacity of exercises in resistance training for individuals with respiratory dysfunctions, presented a significant improvement in the performance of postural control. However, there was no evident significance in the evaluation exercises that also addressed resistance training.

Conclusion

In conclusion, postural control techniques or interventions used in patients with respiratory dysfunctions were more evident in patients with COPD, with a large variety of techniques, but with evaluation methods of recognized quality. There was no demonstration of superiority of one technique when compared to another and in addition, we noticed an extensive methodological variation between the interventions, which hinders the production of a greater level of evidence. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out a larger number of randomized studies involving this population and the intervention techniques.

References

- Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, et al. (2017) Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195(5): 557-582.

- (2013) The Cost of COPD.

- (2017) COPD: A focus on high users – Infographic, CIHI.

- WHO (2017) WHO, Asthma WHO.

- Eisner MD, Iribarren C, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, Ackerson L, et al. (2011) Development of disability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: beyond lung function. Thorax 66(2): 108-114.

- Porto EF, Castro AAM, Schmidt VGS, Rabelo HM, Kumpel C, et al. (2015) Postural control in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 10: 1233-1239.

- Nici L, Zu Wallack RL (2014) Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Definition, Concept, and History. Clinics in Chest Medicine 35(2): 279-282.

- Beauchamp MK, O’Hoski S, Goldstein RS, Brooks D (2010) Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on balance in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91(9): 1460- 1465.

- Bezzoli E, Andreotti D, Pianta L, Gibbons S, Salvadori A, et al. (2016) Can specific motor control exercises for the lumbar-pelvic region improve motor and respiratory performance in obese men? A pilot study. Man Ther 25: e80.

- Marques A, Jácome C, Cruz J, Gabriel R, Figueiredo D (2015) Effects of a Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program With Balance Training on Patients With COPD. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 35(2): 154-158.

- Beauchamp MK, Janaudis Ferreira T, Parreira V, Romano JM, Woon L, et al. (2013) A randomized controlled trial of balance training during pulmonary rehabilitation for individuals with COPD. Chest 144(6): 1803-1810.

- Gloeckl R, Jarosch I, Bengsch U, Claus M, Schneeberger T, et al. (2017) What’s the secret behind the benefits of whole-body vibration training in patients with COPD? A randomized, controlled trial. Respir Med 126: 17-24.

- Kovacikova Z, Neumannova K, Rydlova J, Bizovská L, Janura M (2017) The effect of balance training intervention on postural stability in children with asthma. J Asthma 55(5): 502-510.

- Holmes ML, Manor B, Hsieh WH, Hu K, Lipsitz LA, et al. (2016) Tai Chi training reduced coupling between respiration and postural control. Neurosci Lett 610: 60-65.