Designing for Health and Appetite: A Survey of Appropriate Environments to Achieve Meal Time Satisfaction in Dementia Residents and Participants

Valencia B Keen*, Laura Burleson, Kristin Kabay, Leslie Boyd and Allison Beck

Sam Houston State University, USA

Submission: December 07, 2017; Published: February 23, 2018

*Corresponding author: Valencia B Keen, Undergraduate and Graduate Faculty, Sam Houston State University, USA, Tel: 936-294-1245, Email: vbk001@shsu.edu

How to cite this article: Valencia B Keen, Laura Burleson, Kristin Kabay, Leslie Boyd, Allison Beck. Designing for Health and Appetite: A Survey of Appropriate Environments to Achieve Meal Time Satisfaction in Dementia Residents and Participants. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2018; 5(4): 555666. DOI: 10.19080/NFSIJ.2018.05.555666.

Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study was to assess current practices used by facilities caring for dementia residents or participants to determine their understanding of the benefits of appropriate foodservice environmental design which may contribute to meal satisfaction and reduce unintentional weight loss.

Study design: One hundred and fifteen surveys were provided to facility administrators to assess knowledge of menu and facility design to achieve meal time satisfaction.

Setting/Participants: Thirty-one facilities completed the survey, including elder residential communities, elder daycare support communities, an inpatient acute care hospital, an acute care/rehab unit, and a Meal on Wheels Senior Center.

Results: Fifty-five percent of administrators surveyed allow their dementia participants/residents an hour or longer to consume their meals. Seventy-one percent of facilities use plated meal service and only two facilities use family meal service. Forty-two percent of facilities play background music during periods of eating but no specific design was identified routinely to enhance appetite in all the facilities. Many of the facilities provide the dementia patient with special one-on-one attention or allow family members to assist with serving and feeding the patient if they have forgotten to eat. Supplementation between meals (45.2%) and supplementation with meals (35.2%) were the most prevalent methods to manage unintentional weight loss of the dementia residents. The chefs at the facilities add foods high in specific nutrients to the menu for dementia patients, including omega-3, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and folate. Only 45.2% of the facilities report routinely performing Subjective Global Assessment on their dementia patients/residents.

Conclusion: There are still gaps present in the implementation of policies of specific design that were obvious to enhance food intake and mealtime satisfaction in dementia residents and or participants. It is apparent that many administrators of facilities need to be educated on the appropriate care to enhance mealtime satisfaction and ensure that dementia patients are receiving proper nutritional care.

Potential implications: Education programs tailored to enhance the knowledge of facilities personnel would be beneficial in the facilities effort to maximize meal satisfaction in the dementia patient.

Keywords: Dementia; Meal Time; Designing; Daily living; Food; Music;

Introduction

Challenges

Currently 13.9 percent of Americans age 71 years and older are living with dementia, while 5 million Americans, 65 years and older have Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia [1]. As we Americans and the rest of the world ages, the risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease increases, and the prevalence of the disease almost doubles every five years after the age of 65 [2]. As the disease progresses, it becomes increasingly more difficult to care for individuals, and by age 80, 75 percent with the disease are estimated to reside in a long-term care facility such as a nursing home, to receive specialized care for help with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), activities of daily living (ADLs), administration of medications, management of behavioral symptoms, and adherence to treatment recommendations [1].

Further complicating dementia and Alzheimer's care are problems with food intake, creating one of the biggest challenges for facilities caring for dementia patients. Research indicates that difficulties with food intake arise due to a multitude of problems and begin during early stages of the disease, worsening in the mid to latter stages causing unintentional weight loss and malnutrition [3-8]. To improve problems associated with food intake and enhance mealtime satisfaction in dementia and Alzheimer's residents/ participants, we began to explore the literature and examine if core elements of foodservice style, environment, and nutrition assessment were consistent in the US and worldwide.

Paramount in the care of dementia residents is the creation of a home-like environment while simultaneously addressing each patient’s specific individual dining needs [5,9]. Researchers highlight the importance of inside and outside space and design characteristics in the dining environment, indicating these characteristics may be the most important elements affecting food intake. In addition, design elements in the dining area such as lighting, tableware, eating utensils, color patterns (e.g. use of contrasting colors), linens, sound (e.g. music vs. noise), and temperature may all play a key role in environmental stimulation [6,7,9-11]. By manipulating these factors, dementia and Alzheimer's residents or participants may experience less confusion and anxiety from the environment leading to improved food intake.

Wansick's [11] research helped establish many of the originating principles behind factors, which help increase and decrease food intake. Wansick's research suggested that characteristics such as soft lighting, temperature, odors, and noise management, may influence food consumption by increasing eating duration, comfort, and enjoyment. It was also found that preferred or familiar soft music increased consumption of food and drinks while music or ambient noise that was too loud or fast, created discomfort during dining [11]. These findings may encourage the use of soft familiar music played during dining to increase food intake in dementia and Alzheimer's patients. Music was found to stimulate and calm the senses, allowing patients to experience less anxiety at mealtimes further helping to increase food intake [5,12]. Dementia and Alzheimer's patients also commonly experience difficulty eating due to a lack of visual contrast. Several studies [6,10] report that patients frequently experience trouble seeing plate-ware due to problems with perception of color contrasts and depth, and suggest using high contrast colors such as red or blue between plates, tables, and place settings to increase food intake. Poor lighting may also contribute to problems with visual contrast and cause glares on glossy surfaces making surfaces difficult for the dementia patient to see. Poor lighting may also play a role in sun downing, a common problem at dusk, which may be associated with falling light levels [10]. To help correct these issues, facilities caring for dementia patients may add or brighten light sources, which may also help to guide light to reflect off walls and not off glossy surfaces creating glares [6,9,10]. In addition, other researchers have found that enhancing aesthetics of the dining area with the use of tablecloths, placemats, flowers, and festive place settings may also help to increase appetite and food intake in dementia and Alzheimer’s patients [3,11,13,14]. To affect appetite, interior design research by Warner [15] reveals colors in reds and oranges are known to stimulate appetite while some blues may deepen in tone to appear black and consequently be seen as a space or hole.

Finally, changes to foodservice elements such as food choices and meal practices may provide additional approaches to increase food intake. Studies suggest an increase in food selection (e.g. serving favorite or culturally familiar foods and variety of foods), use of finger foods, providing supplements, frequent snack times, serving nutrient dense foods, and mealtime assistance may also facilitate increased food intake [5,7,8,11,16,]. Wansick [11] found that variety provided during meals increased the volume of food eaten and thus, may be one of the easiest ways to promote food intake in dementia and Alzheimer's patients. Additionally, providing nutrient dense foods containing vitamin B12 and B6, folate, and omega-3 fatty acids with antioxidant rich spices, may deliver healthful protective nutrients and sufficient calories even if small amounts of foods are consumed at meals [16]. Some research even points to the benefits that antioxidants may impose on the development of Alzheimer’s disease producing less oxidative stress in the brain [17].

Simmon (2008) reported that providing feeding assistance promoted food and fluid intake, increasing oral intake in patients at risk for weight loss. Even various types of food service selection surrounding meal practices such as serving family-style meals has been shown to improve quality of life and therefore may increase food intake in patients [4,5,13,14]. Research also shows that snacks given between meals improved caloric intake and weight gain in patients. Several studies [7,8] also report on the benefits of supplement use and found nutritional status improved when staff followed protocol in administration and assisted patients with their consumption.

It was hypothesized that choices in food selection, foodservice style, environment, and nutrition assessment made by registered dietitians, chefs, foodservice operators in facilities caring for dementia participants or residents, play a pivotal role in enhancing meal-time satisfaction, ultimately reducing unintentional weight loss and malnutrition.

The objective of this study was to assess practices used by facilities caring for dementia patients to determine their understanding of the benefits of appropriate core elements of foodservice style, foodservice environment, and nutrition assessment to the meal satisfaction in the dementia patient.

Methods

A descriptive study design was used to assess the current practices associated with the care of the dementia patient. A survey was developed based on research which indicated that dining environment, style of meal service, and specific nutrients can benefit dementia patients and prevent malnutrition in the dementia patient. The survey includes items in the areas of style of foodservice for dementia residents or participants, design of dining environments for dementia residents or participants, nutrition issues related to menus for dementia residents or participants, and nutrition assessment of dementia residents or participants. The questionnaire survey was used to determine the administrator's knowledge of providing an adequate menu and designing a dining service that is appropriate for achieving meal time satisfaction in dementia patients/residents.

The sample was selected by identifying and targeting those facilities that care for dementia residents/participants. Potential facility participants were contacted by email or in-person by one of the research members. Only one attempt was made for the requested response. A letter of informed consent was provided to all potential facility participants after IRB approval. One hundred and fifteen facilities were contacted to participate in the study. Thirty-one facilities agreed to participate and returned the completed survey. Therefore, a response rate of 27% was achieved for this research. Survey questions included description of foodservice, style of dining facilities, type of lighting provided and occurrence of day lighting in the space, common colors for table setting and table coverings and whether there were patterns used. The questions further included responses on music and noise levels and whether clutter was on the table. Nutritional assessment centered on menu use, hydration levels, eating episodes and supplements needed or provided (see appendix for survey).

Results

The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics performed using SPSS. Frequency analysis was used to tabulate the qualitative data of facility participant responses.

Type of Care

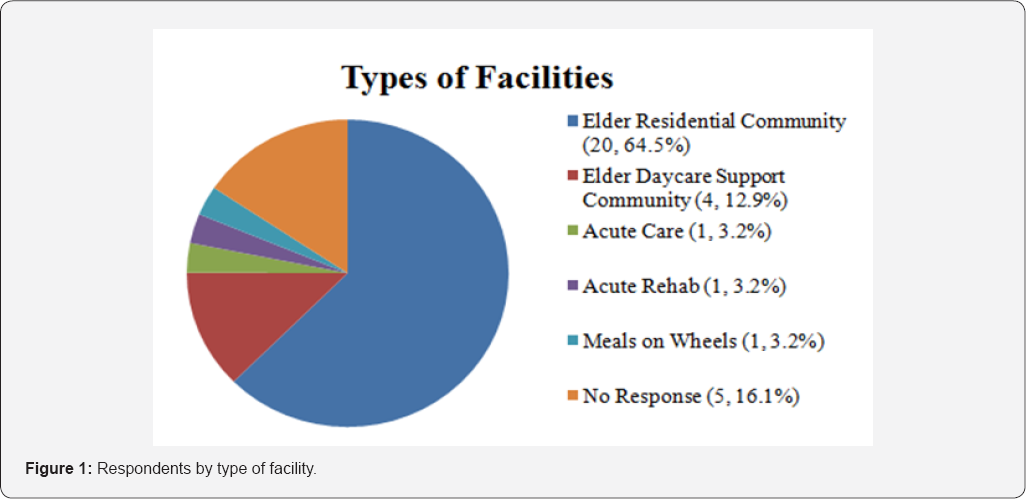

Thirty-one facilities which care for dementia patients participated in the research and completed the survey. Facilities include twenty elder residential communities, four elder daycare support communities, one inpatient acute care hospital, one acute care/rehab unit, and one Meal on Wheels Senior Center (Figure 1). Five facility respondents did not indicate the type of facility they work in. Ten of the thirty-one facilities (32.3%) indicated that the facility included dementia patients (Figure 1).

Style of food service

Fifty-five percent of facility participants indicated that dementia patients were allowed at least an hour to consume their meals and many facilities allow as much time as needed. Seventy-one percent of respondents used plated meal service for dementia patients. Two facilities report using family style meal service and the acute care hospital used hospital tray service. All facilities indicated that they used strategies to manage dementia patients that have forgotten to eat. Twelve facilities (38.7%) provided the dementia patient with special one on one attention in order to ensure that they have eaten. Nine facilities (29.0%) reported that family members were present at the facility to assist with serving and feeding the patient. Other relevant responses regarding methods used to manage dementia patients who forgot they have eaten include "we remind the patient of their last meal and their next meal" and "we sit and eat with our residents to ensure they are eating; we engage in conversation as we eat for reminders."

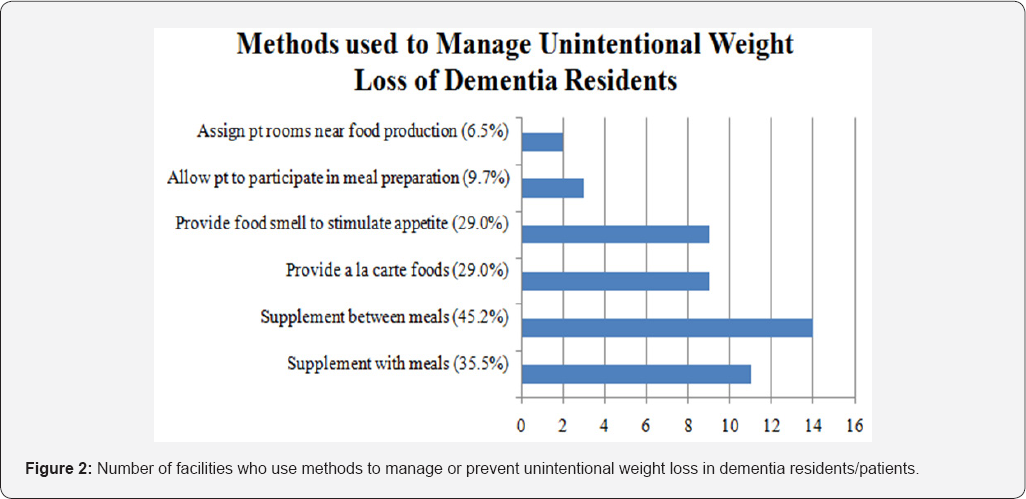

Eleven facilities (35.5%) managed unintentional weight loss by supplementing with meals and fourteen facilities (45.2%) reported supplementing between meals. Nine facility administrators (29.0%) reported providing a la carte foods to manage unintentional weight loss and nine facility administrators (29.0%) reported providing food odors or automatic air fresheners to stimulate patient appetite. Three facilities (9.7%) reported allowing dementia residents to participate in meal preparation to manage unintentional weight loss. Two facilities (6.5%) reported strategically assigning dementia resident rooms near food production so odors of cooking foods could possibly enhance appetite (Figure 2). Finger foods are served to dementia residents on an "as needed" basis in the majority of the facilities for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks. Twenty-eight facilities (90.3%) served finger foods to their dementia patients (Figure 2).

Design of food service

The use of contrasting colors on place settings for dementia patients were distributed among the following categories: 22.6% used neutral colors with low contrast, 16.1% used neutral colors with high contrast, 22.6% used chromatic colors with low contrast, and 19.4% used chromatic colors with high contrast. Fifteen facilities (48.4%) reported they did not avoid or rarely avoided patterned dishes or table coverings with their dementia patients. Sixteen facilities (51.6%) reported avoiding patterned dishes or table coverings.

Design of environment

Thirteen facilities (41.9%) reported providing background music during periods of eating. When asked what type of music was provided, the following responses were given: "Soft," "oldies," "big band but softer familiar tunes," "country, easy listening," "classical," and "resident's choice, usually determined by their age group." All facilities indicated that the music was turned down some or turned down low during periods of eating.

Twenty-one facilities (67.7%) report that dining tables or dining surroundings were not allowed to accumulate clutter. Twelve facilities (38.7%) reported selecting neutral colors with high contrast for the dining facilities used by dementia residents/patients while 22.6% used neutral colors with low contrast, 16.1% used chromatic colors with low contrast, and 12.9% used chromatic colors with high contrast. Twenty- one facilities (67.7%) reported that they did not avoid visual patterns within dining facilities to enhance appetite in dementia patients.

The lighting used by the facility administrators varied widely with one facility (3.2%) used dim lighting, ten facilities (32.3%) used medium lighting, and four facilities (12.9%) used high lighting. Twenty facilities (64.5%) used day lighting, and three facilities (9.7%) used only artificial lighting.

Nutrition issues related to menu

Fifteen facilities (48.4%) indicated using specific foods and nutrients intentionally when writing menus for dementia residents/patients. Blueberries were routinely served in

45.2% of facilities, cranberries were routinely served in 35.5% of facilities, strawberries were routinely served in 58.1% of facilities, broccoli was routinely served in 64.5% of facilities, kale was routinely served in 6.5% of facilities, and spinach was routinely served in 64.5% of facilities (Figure 3).

The chefs at many of the facilities added foods high in specific nutrients to the menu for dementia patients, including omega-3 (41.9%), vitamin B6 (25.8%), vitamin B12 (41.9%), and folate (29.0%). A high carbohydrate meal was not typically provided for supper (67.7% did not provide) to dementia participants. The Mediterranean or DASH diet was not promoted in 58.1% of facilities. Ten facilities (32.3%) reported offering commercial supplements to the dementia residents/participants. The majority (58.1%) of facilities did not encourage the use of curry, cumin, and/or turmeric as seasonings for food. At least 75% of participants reported providing residents/participants with water, tea, coffee, and juice throughout the day and some facilities provide milk, lemonade, flavored waters and warm drinks in the winter to their patients.

Nutrition assessment

During the initial intake records, twenty-one facilities (67.7%) reported asking the dementia residents about their favorite foods. Fifteen facilities (48.4%) reported enhancing calories in the menu of dementia patients, fourteen facilities (45.2%) reported enhancing the protein sources in the menu of dementia patients, sixteen facilities (51.6%) reported enhancing snack options in the menu of dementia patients, and eight facilities (25.8%) reported using other strategies to enhance nutrient intake in dementia patients, including "trying to get them to eat a balanced diet," "supplements," and "high calorie homemade food and shakes." Eighteen facilities (58.1%) indicated that repeat B12 testing was not ordered every two years by the doctors in their facility. Fourteen facilities (45.2%) reported that their staff, DTR, RD, or Nursing performs Subjective Global Assessments on all of their dementia residents/patients.

Discussion

Recognizing the characteristics that enhance the dining experience for dementia residents and encouraging them to consume adequate calories and nutrients is essential for all members of the healthcare team, specifically registered dietitians. The environment in which dementia residents consume meals plays an integral role in food consumption and mealtime satisfaction in these residents/participants. There are numerous factors that can influence food consumption in elderly dementia residents/participants. However, this research demonstrates that not all facilities that serve dementia patients utilize such interventions and activities to increase consumption.

Playing soft, calming music at mealtimes has been found to positively affect food intake among dementia patients and decrease agitated behaviors that are often presented by dementia patients at mealtimes [11,12,18]. Of the facilities surveyed in this research, 41.9% reported providing background music during periods of eating. This demonstrates the fact that some dementia facilities currently utilize this practice of playing soft, calming music during mealtimes in order to enhance food consumption. Brush & Calkins [6] suggested that using high contrast colors such as red or blue between plates, tables, and place settings may increase food intake due to the enhanced visibility of the plate ware and food items for dementia patients. However, only 19.4% of the facilities used chromatic colors with high contrast for the dining room used by dementia residents/patients. This insinuates a possible need to educate all dementia facilities about the benefits of utilizing high contrast colors for dining room place settings and encourage them to try such an intervention at their establishment. The type of lighting used in the dining room can also influence the consumption of dementia patients. Poor lighting hinders the patient's ability to see their food and thus negatively impact intake. Conversely, the use of bright lighting can enhance the patient's intake by helping them recognize and respond to the eating process in a more appropriate manner [19]. This research investigated numerous types of lighting utilized by the facilities. Only 12.9% of the facilities reported using high light levels, while 64.5% reported using day lighting in the dining room. The low percentage for use of high light levels suggests that facilities should be informed of the responses that can be evoked by the dementia residents during mealtimes when high light levels are utilized. It is proposed that the facilities experiment with the use of high lighting and determine whether the intervention results in a positive response. The type of lighting should be tailored to the specific facility and their patients.

Alterations to food service elements such as food choices and meal practices may also increase food intake. Specifically, the use of finger foods has demonstrated a positive effect on food consumption and mealtime satisfaction in the patient [19,20]. Finger foods can promote independence and allow more opportunities for dementia patients to self-feed [19]. The serving of finger foods in facilities that serve dementia patients appears to be quite common, a step in the right direction of eradicating inadequate food intake and loss of independence in the dementia patient. Providing the dementia patient with supplements during or between meals can also enhance intake and decrease the incidence of unintentional weight loss [7,8,19]. Less than half of the facilities reported supplying dementia patients with supplements at various times in order to avoid unintentional weight loss. This demonstrates the need for education among facilities that serve dementia patients about the essential role that supplements can play in preventing unintentional weight loss. A variety of supplements may be tested among residents in order to determine the product that is well-accepted among the patients. Allowing the dementia patient to participate in meal preparation may also help manage unintentional weight loss. The involvement may help some people with dementia to develop and maintain an interest in food and possibly stimulate appetite [20]. Only 9.7% of the facilities reported allowing dementia patients to participate in meal preparation. Other facilities should consider this intervention, if feasible for the patient and the nature of the establishment, in order to enhance intake and prevent unintentional weight loss [21-22].

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that there are still gaps present in the implementation of policies and activities related to universal design that can be used to enhance food intake and mealtime satisfaction in dementia patients, residents or participants. It is apparent that many facilities need to be educated on the appropriate care supported by research to enhance mealtime satisfaction and ensure that dementia patients, residents or participants are receiving proper nutritional care. Dementia patients are an extremely vulnerable population and it is the responsibility of the healthcare provider, registered dietitian, and/or interior designer to ensure that good nutrition is enhanced and achieved. It is essential that facilities are provided with this knowledge in order to reach nutritional goals and eradicate the nutritional risk that plagues millions of dementia patients, residents or participants. Part of the problem in establishing protocols and universal design is that there are very few studies that have looked at either participants of Elder Day Cares with dementia, or patients or residents with dementia.

References

- Alzheimer's Association (2013) 2013 Alzheimer's disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer's Dement 9(2): 208-245.

- US Department of Health and Human Services (2011) National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Aging. Health and Aging.

- Abbott RA, Whear R, Thompson-Coon J, Ukoumunne OC, Rogers M, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of mealtime interventions on nutritional outcomes for the elderly living in residential care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 12(14): 967-981.

- Verbrugghe M, Beeckman D, Van Hecke A, Vanderwee K, Van Herck K, et al. (2013) Malnutrition and associated factors in nursing home residents: A cross-sectional multi-centre study. Clin Nutr 32(3): 438443.

- Dorner B, Friedrich EK, Posthauer ME (2010) Position of the American Dietetic Association: individualized nutrition approaches for older adults in health care communities. J Am Diet Assoc 110(10): 15541563.

- Brush J, Calkins M (2008) Environmental interventions and dementia: enhancing mealtimes in group dining rooms. ASHA Leader 13(8); 2425.

- Kayser-Jones J (2006) Use of oral supplements in nursing homes: remaining questions. The American Geriatrics Society 54(9): 14631464.

- Suominen M, Muurinen S, Routasalo P, Soini H, Suur-Uski I, et al. (2005) Malnutrition and associated factors among aged residents in all nursing homes in Helsinki. Eur J Clin Nutr 59(4): 578-583.

- Dewing J (2009) Caring for people with dementia: noise and light. Nurs Older People 21(5): 34-38.

- Lenham J (2013) Colour, contrast and comfort: interior design in?dementia. Nursing & Residential Care 15(9): 616.

- Wansink B (2004) Environmental factors that increase the food intake and consumption volume of unknowing consumers. Annu Rev Nutr 24: 455-479.

- Smith M, Smith E, Papa K (2010) Building empathy based care through creative expression. Alzheimer's Resource Center 1-3.

- Venturato L (2010) Dignity, dining, and dialogue: reviewing the literature on quality of life for people with dementia. I Int J Older People Nurs 5(3): 228-234.

- Robinson G, Gallagher A (2008) Culture change impacts quality of life for nursing home residents. Topics in Clinical Nutrition 23(20): 120130.

- Warner C (2017) How Interior Design Can Affect The Health and Wellbeing of Seniors.

- Turner J (2011) Your Brain on Food: A Nutrient-Rich Diet Can Protect Cognitive Health. Generations, 35(2): 99-106.

- Berstein M, Munoz N (2012) Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Food and Nutrition for Older Adults: promoting Health and Wellness. J Acad Nutr Diet 112(8): 1255-1277.

- Watson R, Green S (2006) Feeding and dementia: a systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs 54(1): 86-93.

- Morris J, Volicer L (2001) Nutritional Management of Individuals with Alzheimer's Disease and Other Progressive Dementias. Nutrition in Clinical Care 4(3): 148-155.

- Manthorpe J, Watson R (2003) Poorly served? Eating and dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing 41(2): 162-169.

- Duffin C (2008) Designing care homes for people with dementia. Nurs Older People 20(4): 22-24.

- Morley J, Silver A (1995) Nutritional issues in nursing home care. Ann Intern Med 123(11): 850-859.