Employees with Disabilities in Special Employment Centers Perceptions: Similarities and Differences Considering Educational Level

Marina Romeo* and Montserrat Yepes-Baldó

Director of the University Chair, University of Barcelona-Fundación Adecco, Spain

Submission: December 11, 2018;Published: January 11, 2019

*Corresponding author: Marina Romeo, Full professor and Director of the University Chair, University of Barcelona-Fundación Adecco, Spain

How to cite this article: Marina Romeo, Montserrat Yepes-Baldó. Employees with Disabilities in Special Employment Centers Perceptions: Similarities and Differences Considering Educational Level. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2019; 5(5): 555672. DOI:10.19080/GJIDD.2019.05.555672

Abstract

It is usually considered that the worker with disability experiences job satisfaction just for having a job. In this context, we analyze the reality of people with disabilities in Special Employment Centers (SEC), given their important role as employers of this group during the years of economic crisis. The degree of satisfaction, motivation, commitment, and perception of employability, according to the educational level, of employees with disabilities is compared. Employees with or without university studies, feel motivated, committed and willing to continue in the SEC where they work, although the levels of satisfaction in relation to their work are moderate. Disabled employees with higher education have a greater perception of employability, either in general company or in another special employment center, contributing to the empowerment of the employees, giving them a perception of competence and self-efficacy.

Keywords: Motivation; Satisfaction; Commitment; Employability; Special Employment Centers; Employees with Higher Education Studies.

Introduction

The main objective of the present research, elaborated on the framework of the University Chair of Barcelona-Fundación Adecco for the labor inclusion of people with disabilities, was to analyze the reality of people with disabilities in Special Employment Centers (SEC), given their important role as employers of this group during the years of economic crisis.

Different questionnaires evaluating job satisfaction, motivation and organizational commitment were used. All these questionnaires were part of the Human System Audit, developed by Quijano [1]. The questionnaire HSA-SAT was used to measure job satisfaction. This questionnaire analyzes the level of satisfaction with economic retribution, physical conditions in the work environment, job security and stability that the company offers, relationships and colleagues at work; support of superiors; recognition of work well done, and the possibility of learning and personal development at work. The questionnaire uses a 5-points Likert scale (1: very dissatisfied, 5: very satisfied) and has an internal consistency of 0.90 [2].

To measure motivation, the administered questionnaire was the HSA-MOT, that measures the level of general motivation (3 items) and its antecedent psychological processes (10 items). The psychological processes analyzed are self-efficacy (belief, on the part of the subjects, that they are capable of giving effective answers to the demands of the job), equity (perception of balance between what the employee receives from the organization and what he or she contributes to it, compared to what others contribute and receive), awareness of results (knowledge of the results obtained from the work), responsibility for results (the employees are aware that the results of their work depend mainly on themselves, and not on chance or other external factors), and the perceived meaning (degree in which the employees conceive that their work is an important activity for the company, recognized by the members of the organization, and whose results have an impact on other people inside or outside the organization). The internal consistency of the general motivation scale measured by Cronbach’s alpha is 0.68 [3]. Its criterion validity, proven through its correlation with the intrinsic work motivation scale [4] is 0.63 [3].

To measure organizational commitment, the validated Identification-Commitment Inventory (ICI) [5] was used. This inventory distinguishes four dimensions of commitment: values commitment (the most intense link between the employees and their organization, based on the congruence between the values of the individual and those of the organization), affective commitment (understood as an emotional link established between the employee and the organization), exchange commitment (link based on the perception of equity between the efforts of or costs for the employee with respect to the remuneration or benefits received), and need commitment (the employee’s relationship is minimal and is determined by the individual’s need to continue being a member of the organization). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale is .94 [5].

The intention to quit was measured from a single item (“I am going to look for a new job next year”), and for the perception of employability a scale was developed ad-hoc in which employees were asked to assess the possibilities that they consider in order to find work in another SEC, or in a general company (perception of external employability), as well as the probabilities of changing positions within the same organization (perception of internal employability). Finally, the level of education was measured, and employees were classified into two groups: with or without university studies.

Results and Conclusion

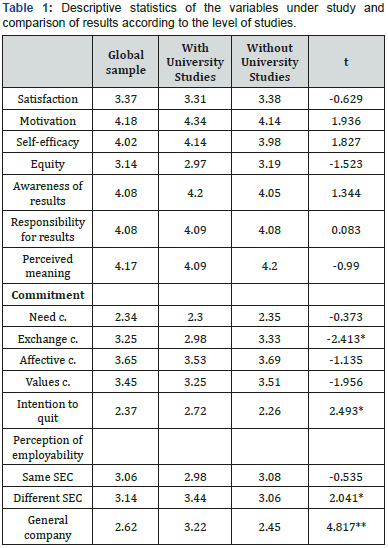

After contacting 20 SEC, we finally received answers from 234 SEC employees in Spain. Results show that both, employees with university studies and without them, felt motivated, committed and were willing to continue in the SEC where they were working although the levels of satisfaction, in relation to their work, were moderate (Table 1).

*p<.05; **p<.001

High levels of motivation were also reflected in the employees’ perception of being able to give effective answers to the demands of the job (self-efficacy). In addition, outstanding levels of knowledge of the results obtained from their work, a marked sense of responsibility for these, and the perceived importance of their activity were found. To all this, it should be added that both groups claim to have a medium-high emotional link with their organization (affective commitment).

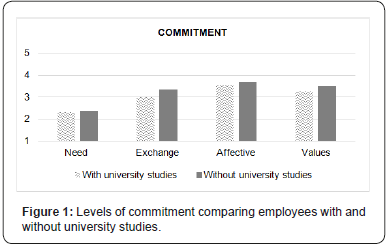

Comparing both groups, significant differences were observed in the link established by the employees with the organization based on the perception of balance between what they contribute (effort, dedication, hours of work, ...) and what they receive in return (working conditions , salary, hours, ...) (exchange commitment) (Figure 1), the perception of employability and the intention to continue forming part of the SEC.

Specifically, people with higher education perceived that they were more likely to find work in the general market and / or in another SEC than people with primary or secondary education levels. In contrast, employees without university studies had higher levels of exchange commitment than people with higher education. Regarding the intention to remain in the SEC, the results indicated that both wished to remain in their companies (scores below 3 on a scale of 5 points), although there were significant differences between both groups. Employees without university studies were those who most wanted to continue working in their SEC (Figure 2).

This research contributes to the analysis of the perceptions of employees in Special Employment Centers, given the paucity of studies concerned about the set of variables that affect the quality of working life of employees with disabilities. In this sense, our results show that SEC workers feel motivated and committed affectively with their organization. To these results, we must add their high awareness and responsibility regarding the results they obtain with their work and, in addition, the consideration that the activity they perform is important and recognized by their colleagues and managers.

Comparing the group of employees with disabilities, with and without higher education, it is observed that the former has a higher perception of employability, either in general companies or in another special employment center. In this sense, a university degree favors the empowerment of the employees, by giving them a sense of competence and self-efficacy and enabling them to perform behaviors aimed at achieving results [6-9]. Hence, we can affirm that university education contributes to “selfdetermination and autonomy, so these employees can exercise more influence in decision making and, in this way, improve their self-esteem, autonomy and in general, their quality of life” [10].

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no economic interest in or conflict of interest.

References

- Quijano S, Navarro J, Yepes Baldó M, Berger R, Romeo M (2008) Human System Audit (HSA) for the analysis of human behaviour in organizations. Papeles del Psicólogo 29(1): 92-106.

- Quijano S, Navarro J, Cornejo JM (2000) An integrated model of commitment and identification with the organization: analysis of the ASH-ICI questionnaire. Revista de Psicología Social Aplicada 10(2): 27- 60.

- Navarro J, Yepes Baldó M, Ayala Y, Quijano S (2011) An integrated model of work motivation applied in a multicultural sample. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones 27(3): 177-190.

- Warr P, Cook J, Wall T (1979) Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well‐being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 52(2): 129-148.

- Romeo M, Yepes-Baldó M, Berger, R, Guardia J, Castro C (2011) Identification-commitment inventory (ICI model): confirmatory factor analysis and construct validity. Quality & Quantity 45(4): 901-909.

- Bejerholm U, Björkman T (2011) Empowerment in supported employment research and practice: Is it relevant. Int J Soc Psychiatry 57(6): 588-595.

- Heritage Z, Dooris, M (2009) Community participation and empowerment in healthy cities. Health Promotion International 24: 145-155.

- Rich Edelstein M, Hallman WK, Wandersman AH (1995) Citizen participation and empowerment: The case of local environmental hazards. Am J Community Psychol 23(5): 657-676.

- Zimmerman M (2000) Empowerment theory. In: Rappaport J and Seidman E Handbook of community psychology Kluwe, New York, USA, pp. 569-579.

- Suriá R (2013) Disability and empowerment: analysis of this potential based on the type and stage in which the disability is acquired. Anuario de Psicología 43(3): 297-311.