The Association of Smoking Addiction and Depression in Smokers

Siripan Phattanarudee*

Chulalongkorn university, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Thailand

Submission: September 06, 2018; Published: September 21, 2018

*Corresponding author: Siripan Phattanarudee, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn university.

How to cite this article: Siripan Phattanarudee. The Association of Smoking Addiction and Depression in Smokers. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018; 5(2): 555660. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2018.05.555660

Abstract

The tobacco addiction is an interrelation of nicotine addiction, psychological, and sociobehavioral addictions. Smoking or Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of premature morbidity and mortality, however smokers find it difficult to quit successfully. Depression, a mood disorder, was found in both smokers and non-smokers, but the prevalence of depression was reported to be higher in smokers than non-smokers. Smoking addiction, as a result of nicotine addiction, psychological or sociobehavioral addiction might be related to depression. The objective of the study was to examine the association of smoking addiction with the depression, as evaluated from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The results of the study supported that the nicotine addiction, psychological/sociobehavioral addiction were associated with depression. From this study, we suggested that depression should be evaluated for helping the smokers to quit tobacco.

Keywords: Smoking; Nicotine; Addiction; Depression

Introduction

It has been well-known that tobacco addiction produces devastating health consequences, including premature death in smokers and it is the most important avoidable cause of health disability and premature death in the population[1]. In addition, stop smoking has been shown to reduce the deleterious effects, e.g., reducing the rate of decline of lung function (determined by forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1) approximately to that of the never-smoker [2].Smoking cessation is also associated with a 36-50% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary heart disease [3]. However, smoking prevalence is still high in many countries, e.g., the report from WHO (at the beginning of 2002), that ~30% of the adult populations of the European Member States were regular smokers [4], or forty-eight million adult Americans were reported for smoke cigarettes[5]. In Thailand, the Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center (TRC) surveyed the situation of tobacco consumed by Thai people during 1991-2006 and found the rate of smoking in Thai people aged older than 15 years old was 21.91%, and 9.54 millions were regular smokers and 1.5 millions were periodic smokers [6]. On the contrary, considering the proportion of smokers who want to quit smoking, it was found that only a small number of smokers are ready to quit, as reported by Velicer et al.[7]. Only 20% of current smokers are ready to stop smoking in the next month, while a higher number of smokers (40%) did not consider about quitting or expressed ambivalence (40%) about stopping smoking[7]. Difficulty of successful quitting are assumed to be the result of nicotine’s huge psychopharmacological effects, genetic influences, and environmental factors.

Nicotine, the psychoactive substance in tobacco, is responsible for the addiction or dependence and is a main factor that cause the withdrawal symptoms when abstinence from smoking. Stimulation of dopaminergic rewarding pathway by nicotine causes the increase of dopamine release in the mesolimbic system and is mainly responsible for both the pleasurable feelings and the smoking addiction [1]. In addition to nicotine’s addiction effect, the psychological and sociobehavioral factors also affect the initiation and maintenance of nicotine dependence and smoking behavior [8]. Psychological factor is explained by that the smokers have paired the pleasurable effects of nicotine with many activities and emotions associated with smoking (e.g., talking on the telephone, driving, being in the work setting, feeling stressed or bored). These situations and emotions become triggers for the urge to smoke, and for many people, smoking become a habitual behavior with little conscious forethought. Social factor is explained by that smoking might be started from having in the environment of smoking e.g., with friends, having party, and therefore when the smokers are in those environments, they smoke. The cigarette smoking therefore can be the result of nicotine, psychological or sociobehavioral addictions, independently or the interrelated of each other.

Depression is among the most common psychiatric disorders and represents a major cause of disability, preventing sufferers from work and pleasure. The prevalence of depression in smokers versus non-smokers is different. The prevalence of depression in smokers (those who smoked every day for at least 1 month) is 6.6% which is significantly higher than prevalence in non-smoker of 2.9% [9]. Moreover, the successful rate of quitting in those smokers with and without depression is different. The smokers without depression showed a higher quitting rate than those smokers with depression (31% versus 14%, p< 0.001) [9]. Depression, therefore, can be an important factor that interferes the quitting process in smokers.To provide the smoking cessation service, 5’A strategy of ask, advice, assess, assist and arrange were recommended, and all health care providers should follow to help the smokers quit smoking[10]. The assessment process of 5’A strategy needs to know about the addiction of smoking whether nicotine, psychological or sociobehavioral factor is the causative factor maintaining the smoking behavior. However, the assessment for the depression in the smokers has not been regularly performed in routine clinical practice and the association of depression and smoking addiction has never been studied. The purpose of this study was therefore to determine the depression in Thai smokers and the association of depression and smoking addiction, as evaluated from the nicotine addiction, psychological and sociobehavioral addictions in Thai smokers.

Materials and Methods

This research was a cross-sectional analytical study, which studied socio-demographic characteristic, the addictions of nicotine, psychological and sociobehavioral addictions of smokers, and their relationship to the depression in smokers. Participants were recruited from smokers attending the clinics for quitting smoking at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital and Police Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, during August and November 2011. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of those hospitals. Smokers were eligible for the study if they were current smokers, aged ≥ 18 years, had not on the medication for depression. Previous study was used to provide a basis for sample size calculation[11], this provided a sample size requirement of 93 subjects. Smokers were also offered counseling with the psychiatrist when the moderate or severe depression was detected. Participants answered three types of questionnaires, including Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence (FTND), the questionnaire for smokers to examine their reasons of smoking (Why You Continue Smoking), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for assessing the current depression. All questionnaires are in Thai language.

The FTND questionnaire comprises of 6 questions and each question has the scores ranging from 0 to 1, or 0 to 3. The questions were:

i. How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette?

ii. How many cigarettes/day do you smoke?

iii. Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden, e.g., at the library, cinema?[4]Which cigarette would you hate most to give up?

iv. Do you smoke more frequently during the first hours of waking than during the rest of the day?

v. Do you smoke if you are so ill that you are in bed most of the day?

The total score was in the range of 0 to 10 and the higher scores represented the higher addiction levels; score 7-10 indicates the heavy or high nicotine addiction, while those lower than 7 indicate the medium (5-6) to low (0-4) level of nicotine addiction.

The questionnaire “Why You Continue Smoking” comprises of 15 different reasons (5 items for each of nicotine, psychological and sociobehavioral addictions) for the participants to examine and choose the ones that they have. The highest score reflects the major cause of smoking. Equal scores indicate more than one causative factor for smoking. Smoking because of psychological addiction include “I smoke because it can make me think better, more energetic, Smoking is one of the pleasurable excitement for life, When I feel relax, it is the time I need to smoke the most, I smoke whenever I am sad or feel distress, Smoking can relieve my stress. Smoking because of sociobehavioral addiction include “I like to smoke after meals or whenever I have time to take a break, I feel comfortable and relax when I have the cigarettes in my hand, Sometimes I found myself are smoking and cannot even remember when I light up the cigarette, I like to see the smoke when I exhale, I feel comfortable when I touch the cigarette, can light up the cigarette”. The nicotine addiction reasons were similar to those found in FTND questionnaire.

The PHQ-9 comprises of 9 questions for depression evaluation[12].The PHQ-9 asks how frequently participants have experienced the nine symptoms of major depression (Anhedonia, Depressed mood, Insomnia or hypersomnia, Fatigue, Appetite fluctuation, Feelings of worthlessness, Diminished concentration, Psychomotor agitation or retardation, and Thoughts of selfharm). The questionnaire reads “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?” Response options are Not at all (score 0), Several days (score 1), More than half the days (score 2), and Nearly every day (score 3).The total score of these symptoms evaluation ranged from 0 to 27 and was used to categorize participants as meeting criteria for “None-minimal depression (score 0-4)”, “Mild depression (score 5-9)”, “Moderate depression (score 10-14)”, “Moderately severe depression (score 15-19), Severe depression (score 20- 27).

Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for socio-demographic data analysis. The association of smoking addiction and depression was done by using Pearson’s correlation statistic and logistic regression analysis. For all of the tests used in this study, the statistically significant level was set at alpha= 0.05. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 14.0.

Results

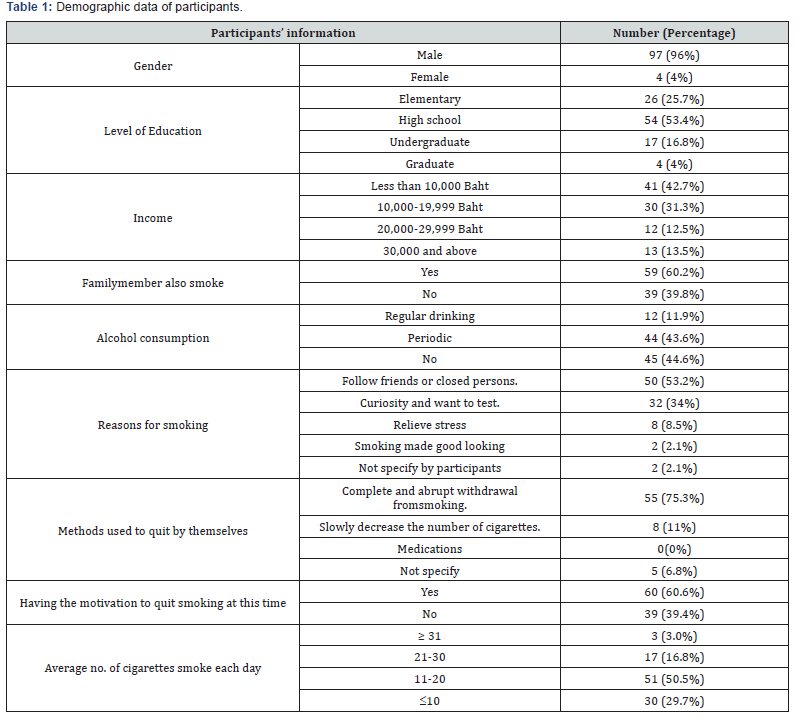

There were 101 subjects attending in this study and male participants (97%) were the majority of them. The average age (mean±SD) of the subjects was 40.08±13.44 years old. They started to smoke at the age (mean±SD) of 16.96±4.49 years old and had the duration of smoking (mean±SD) for 23.14± 13.76 years. Fifty-one percent of participants had the number of cigarettes smoked each day in the range of 11-20 cigarettes. Most of them (60.6%) had the motivation to quit smoking at the time of attending this study.Approximate 75% of the participants had the history of quit attempt (last for at least 24 hours) by not taking any medication, and the average number of quit attempt was 1.76±2.65 (mean±SD) (Table 1).

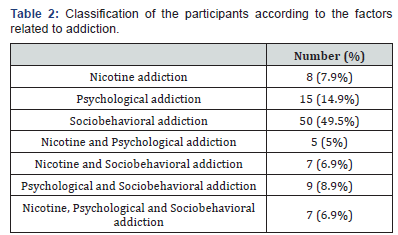

It was found that sociobehavioral factor was the major reason of smoking (49.5%), followed by psychological factor (14.9%) and nicotine addiction (7.9%) (Table 2). Some participants had more than one factor as the cause for smoking addiction. The participants had FTND score of 4.20±2.52 (mean±SD) which corresponded to nicotine addiction of low to moderate level. In accordance with that information, about 50% of participants had the score in the range of low nicotine addiction, and 32% had moderate nicotine addiction, while only 18% had high level of nicotine addiction.

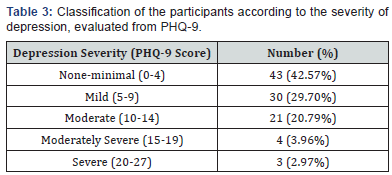

From the PHQ-9 evaluation of the participants, the average score (mean±SD) was 6.39±5.06 which was in the mild depression state. There were about 43% of participants classified as no depression, however mild and more severity of depressions were found in 30% and 28% of participants, respectively (Table 3).

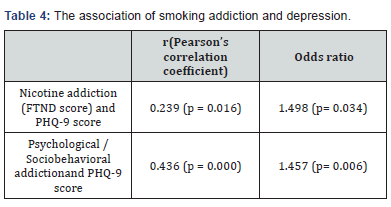

The association of smoking addiction and depression was done by using Pearson’s correlation statistic and logistic regression analysis. The correlation study showed the positive relationship between FTND score of nicotine addiction and the PHQ-9 score of the depression (p< 0.05). Also, the scores from sociobehavioral and psychological addictions were positively correlated with the PHQ-9 score of depression (p< 0.05).From logistic regression analysis which was adjusted for gender, age, level of education, alcohol consumption, and duration of smoking, it was found that nicotine addiction, psychological and sociobehavioral addiction were still associated with PHQ- 9 score, with the odds ratios of 1.498 and 1.457, respectively (Table 4). This suggested that there was an association of nicotine addiction, psychological and sociobehavioral addiction and the increased risk of having depression.

Discussion

From this study, moderate to severe depression was found in about 28% of the participants. The average age of participants of starting the cigarette smoking (16.96±4.49 years old) was similar to those reported by The Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center (TRC), Thailand of 18.25±4.34 years old[6]. In addition, the reasons of smoking found in this study suggested that friends or closed persons and the curiosity were still being the important factors for smoking in the participants. This emphasizes the problem of smoking in the youth and adult which needs to find more strategies to decrease the number of smokers since they were young. The sociobehavioral and psychological factors were found to be the major reasons of smoking in this study. Therefore, the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), group therapy, and counseling methods, in addition to the medication might be helpful for the smokers.

Our data also showed the association of depression and cigarette smoking addiction, suggesting that depression might play an important role in the smoking addiction. However, the mechanisms or directions underlying the association between smoking and depression were not possible to determine in this study. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the possible mechanisms underlying the association between cigarettes smoking and depression[13].

These include

i. The “self-medication” hypothesis which suggested that depression may lead to smoking for relieving the depression symptoms. Other supporting data include that several neurotransmitters released from the neurons as stimulated by the nicotine is similar to those stimulated by antidepressants [14].

ii. Cigarette smoking causes depression as nicotine may cause damage of the neurochemical pathways,

iii. The “bi-directional mechanisms in which smoking and depression reinforce each other. Further analysis for the direction of the association is warranted [13].

Depression is not routinely assessed in the smokers nowadays. Moreover, the questionnaires, including FTND, the questionnaire asking for reasons of smoking do not have the questions concerning the depression symptoms. From this study, we suggest that screening for depression in smokers might be beneficial for help quitting tobacco. Depression can be assessed by using the PHQ-9 questionnaire which has several advantages, including the brief, having good psychometric properties, and having the categorical answers that make it easy to administer by the smokers themselves[11]. The screening for depression can still be useful for referring the smokers to physicians. In that case, the diagnosis of depression can be made by physician and the antidepressant medications may be prescribed to the smokers instead of smoking that the smokers might have thought for help coping the depression.

References

- Benowitz N (2008) Clinical pharmacology of nicotine: implications for understanding, preventing, and treating tobacco addiction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 83(4): 531-541.

- Scanlon PD, Connett JE, Waller LA, Altose MD, Bailey WC, et al. (2000) Smoking cessation and lung function in mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161(2 Pt 1): 381-390.

- Critchley JA, Capewell S (2003) Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA 290(1): 86-97.

- Hylkema M, Sterk P, De Boer W, Postma D (2007) Tobacco use in relation to COPD and asthma. Eur Respir J 29(3): 438-445.

- Cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 1997. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 48(43): 993-996.

- The Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center (TRC) (2007) Thailand.

- Velicer WF, Fava JL, Prochaska JO, Abrams DB, Emmons KM, et al. (1995) Distribution of smokers by stage in three representative samples. Prev Med 24(4): 401-411.

- Pbert LOJ, Reiff Hekking S (2004) Tobacco. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD (Editors.), Textbook of substance abuse treatment. (3rd), American Psychiatric Publishing,Inc, Arlington (VA), USA, pp. 217-234.

- Shiesha S (1999) Selections from current literature: smoking and depression. Fam Pract 16(2): 202-205.

- Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S, Dorfman S, Goldstein M, et al. (2000) Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Maryland, United States.

- Hebert KK, Cummins SE, Hernández S, Tedeschi GJ, Zhu SH. (2011) Current major depression among smokers using a state quitline. Am J Prev Med 40(1): 47-53.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9): 606-613.

- Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O’Loughlin J, Rehm J (2009) A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health 9: 356.

- Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA (2009) A tragic triad: coronary artery disease, nicotine addiction, and depression. Curr Opin Cardiol 24(5): 447-453.