A Cognitively Accessible Digital Storytelling Tool for People with Intellectual and Other Cognitive Disabilities

Daniel K Davies1, Steven E Stock1, Cameron D Davies1, Michael L Wehmeyer*2

1 AbleLink Smart Living Technologies, Colorado Springs, Colorado, USA

2University of Kansas, Beach Center on Disability, Lawrence Kansas, USA

Submission: August 31, 2018; Published: September 20, 2018

*Corresponding author: Michael L Wehmeyer, University of Kansas, Beach Center on Disability, Lawrence Kansas, USA, Tel: 785-864-0723; Email: wehmeyer@ku.edu

How to cite this article: Daniel K D, Steven E S, Cameron D D, Michael L W. A Cognitively Accessible Digital Storytelling Tool for People with Intellectual and Other Cognitive Disabilities.Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018; 5(2): 555659. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2018.05.555659

Abstract

Limited literacy and written expression skills are frequently barriers to self-expression and other forms of social inclusion for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. This article reports a pilot study of a cognitively-accessible iPad® App designed to enable people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to engage in self-expression using multimedia formats. Findings suggest that incorporating cognitive access features can promote self-expression for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Keywords: Intellectual Disability; Self-Expression; Cognitive Access; Developmental Disabilities

Introduction

Students and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities often have difficulty with written language and may have support needs in the area of written composition and written documents [1,2]. Examples of written compositions or documents for which people with intellectual and developmental disabilities may need support include academic products (book reports, essays, field trip summaries), vocational products (multimedia resumes, activity reporting, progress notes), leisure activities (sharing one’s life experiences and perspectives, diary keeping, blogging) or therapeutic supports (feelings journal, documenting personal history). While people with intellectual and developmental disabilities can offer the important insights of their unique perspectives, as well as improve the quality of their lives through self-reflection and other written forms, unfortunately their voices often go unheard as needed supports to enable written expression are too often unavailable.

A common alternative to writing is through oral presentation, either by recording information or through speech-to-text software. But, many people with intellectual and developmental disabilities have concurrent difficulties in verbal communication that limit the utility of recordings or that speech-to-text devices cannot adequately translate. In the age of apps and digital information, there are a myriad of other ways that information can be communicated and that people with limited written expression skills can, in fact, express themselves. This article describes such a device: a cognitively accessible, cloud-based prototype App (called Digital Story Teller or DST) to enable independent self-expression and multimedia documentation of personal stories, thoughts, ideas, experiences, opinions, knowledge, personal history, and other forms of important self-expression. For example, one component of DST provides multimedia prompts to guide a user through the process of taking pictures, recording corresponding narratives, saving, and distributing user-authored multimedia documents that are automatically compiled into readily accessible, common video file formats (e.g., mp4). This is a key element for the DST system because existing personal story telling systems, which have not been designed to be accessible to people with cognitive disabilities, utilize proprietary output formats that limit distribution. In this article we report the development and evaluation of the DST prototype within the context of a personal story telling activity and describe a pilot study that demonstrated the feasibility of this approach for supporting people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to independently create, save, organize and retrieve a series of personal stories.

The Concept of Digital Storytelling and Original Multimedia Composition

Storytelling is a type of self-expression in which one shares stories, narratives, experiences, or anecdotes that tell something about oneself, one’s beliefs, one’s values, and one’s life. Of course, storytelling has existed across time and cultures, and the earliest forms of history were relayed through storytelling. Stories or narratives may be intended to entertain, inform, pass down history, or to document experiences or actions. Journaling, typically involving the regular use of a diary or journal to record thoughts, actions, or beliefs, is common, even in a digital era. The use of storytelling and journaling for academic purposes has considerable precedence in multiple areas. These include applications as a support tool for students with learning disabilities [3], to address stress and classroom management [4], for teaching research methodologies [5], mathematics learning [6]; and as a form of promoting student [7]. Another common form of more intimate self-expressed storytelling is as a therapeutic adjunct [8,9]. The concept has been used in a variety of therapeutic domains, such as completing treatment assignments [10], participating in group therapy [11], treating behavior problems or traumatic stress [12,13], online counseling [14], and other therapeutic contexts.

While these examples provide a background for the range of applications for storytelling methodologies, there is also limited evidence of the use of techniques like journaling by and with people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Keeter and Bucholz [15] demonstrated the efficacy of groupdelivered storytelling as a successful behavioral intervention for students with intellectual disability. Similarly, Paiewonsky [16] documented the use and supports required for digital storytelling as a way for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to engage in participatory action research while chronicling their college experiences.

However, most of the research regarding storytelling and people with intellectual and developmental disabilities appears to be concerning the benefit of receptive storytelling, where people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are not generating personal stories but are instead listening to them or otherwise (potentially) benefitting from third party storytelling. For example, researchers have noted the benefit of multisensory storytelling (MSST) provided by staff to individuals with severe and profound levels of intellectual and developmental disabilities [17]. In summary, while the literature indicates a growing use of storytelling in mainstream society for many different uses, the lack of accessible tools designed for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities appears to limit its utility with that population.

To address this issue, we built and evaluated a prototype of the DST storytelling App that allowed people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to independently create, save, and retrieve brief multimedia compositions. A key feature of the system is the ability to export the resulting multimedia creations and deliver them to teachers or send them to friends and family.

Materials and Methods

A prototype of the DST system was developed (described later in this section) and a feasibility study was conducted comparing the ability for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to independently create multimedia compositions using the DST prototype compared to two other commercially available story creation Apps (Control A, Control B), neither of which were specifically designed to be cognitively accessible. The hypothesis was that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities would be able to create original compositions with less assistance and with fewer errors when using the Digital Storyteller prototype when compared to the other two Apps.

Procedure

For pilot study purposes, all three systems were populated with the same four picture sets (Plants and Flowers, Wild Animals, Ocean Creatures and Birds of Prey) to serve as visual stimulus for storytelling. In both test conditions, the Plants and Flowers category was used during the scripted training process immediately preceding the respective trial condition. Training with each system involved hands on instruction and practice at creating and playing back a sample story. The order of presentation of the three conditions was randomized to control for ordering or learning effects. Following training, participants were allowed to select their desired category of images, and then proceeded to create a multimedia composition using the images for the selected topic. Following completion of the composition, participants then were asked to play back their stories to complete the session.

Participants

Participants included adults with intellectual disability receiving services from a local school district or adult support provider. A total of seventeen people participated in the study, 9 of whom were female and 8 of whom were male. The average age of study participants was 36.06 (SD= 10.65) with an age range from 21-55. The average IQ score for participants was 58.71 (SD= 3.95), with a range of 55-66. Participants were at least 18 years of age and all received community-based services for a variety of life-activity areas, including employment, academic and daily living skills. There were no additional selection criteria other than eligibility to receive services from adult service agencies or school transition programs. Participants (and, if appropriate, parents and guardians) provided consent as approved by the IRB committee, and all participants were paid a stipend for their involvement.

Test Procedures and Experimental Variables

The field evaluation took place over a two-week period near the end of the project. There was one independent variable with three levels representing the three authoring applications used in the study: i) Digital Storyteller, ii) Control App A, and iii) Control App B.

There were two dependent measures: 1) accuracy as measured by the number of errors made during creation of the composition; and 2) independence as measured by the number of prompts required to complete the session. Each App was operated on the same iPad for each participant.

Data Collection

Data collection forms were used to record errors and prompts during each experimental session. The performance of each participant was closely observed by researchers, with verbal prompts and assistance provided when requested or as soon as mistakes were made. In this way, participants always achieved success at the task, even if they needed assistance to achieve it. In addition to the quantitative data collected, there was room provided on the data collection forms to record additional observations as well as statements made by subjects during the test sessions.

Digital Storyteller Prototype Description

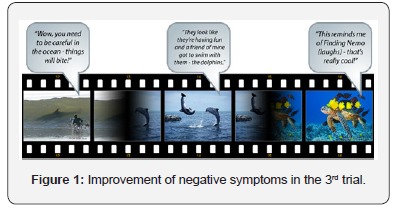

The DST prototype was designed and developed as an App for the iPad® that supported a “storytelling” approach to self-expression. Figure 1 provides an example of a portion of a story created by one test subject. This module provided the opportunity to use a designated set of digital images to create a personal story by selecting images in the desired order and then recording self-conceived, descriptive messages of each. The prototype supported storytelling activities by providing a simple, linear flow and computer-generated audio prompts to guide the user through the process. The prototype DST App, when first launched, displays a Bookshelf metaphor screen. The Bookshelf shows any multimedia books that are currently available. Each book is represented by an image and title, which are assigned by the user during book creation. A user can select a video book to play back (which also plays the audio that was recorded which describes the story) or can choose to begin creating a new book using the New Story button on the bottom of the Bookshelf. In addition, users share their stories with family and friends via email or by posting to social networking sites, such as Facebook. The video books that are shared with others are created as MP4 files, so friends and family will not require any specialized application to play the story. This accomplished one goal of the prototype, to overcome limits to dissemination imposed by proprietary playback formats common with existing story creation tools.

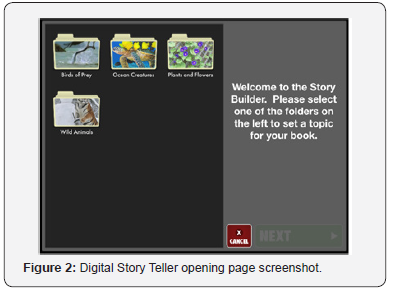

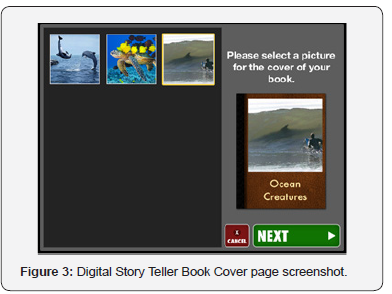

When the New Story button is selected, the system loads picture folders available on the iPad and displays an image from the respective image folder for selection by the story creator while providing audible and text prompts to the user (Figure 2). This «story selection page» is where users select from available pictures sets, or take photos inline using the iPad’s built-in camera, or browse locally or via the web for pictures to include in their stories. This process was developed to allow users to access sets of images they may have taken previously from vacations, sports events, etc. to create a personal story, although this process of incorporating personally obtained images was not within the scope of this study. After the user chooses his or her desired topic by selecting an image folder, Digital Storyteller moves to the Book Cover screen as shown in Figure 3.

When the Book Cover display first opens, a computergenerated audio message plays that prompts the user to “Select a picture for the cover of your book.” When the user selects a picture for his or her book cover, it is displayed on the right of the screen in the book frame. At the same time, a Next button appears below the book frame. Users can change the cover image as many times as desired before clicking the Next button. Users can change the name of the book by tapping the book name text and typing in a name if they have the capability to use the keyboard. Otherwise, the name of the image folder is simply used as the default name for the story. Once a cover image has been selected and Next has been clicked, DST prompts the user to “Please record a message that describes your story” via both text and a computer-generated audio message. The user then clicks the Record button, records the book title, and clicks Stop. At that point, the user may either proceed by clicking the Next button or can use the green Play button to listen to their message. The title message can be re-recorded repeatedly if needed until the user is satisfied with the recording.

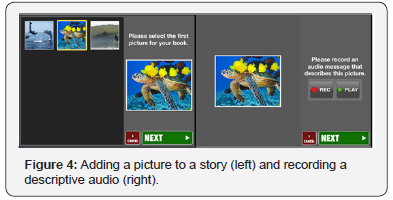

After identifying a picture and title for the story, the user uses the Next button to proceed with creating the “pages” of their story. Story creation follows a repetitive cycle of selecting pictures and recording descriptive messages for each one. Figure 4 shows an example of the DST display when prompting the user to “Select the first picture for your book” on the left, and the subsequent cue to “Now record a message that describes this picture” on the right.

One option that is provided in DST is a «use all pictures in folder» option. With this option, users continue creating their book until all pictures have been used. Thus, as the book building sequence continues, only images that have not been used in the story are displayed for the user to select from. This approach provides an effective interface for users with more extensive cognitive support needs, as they do not have to keep track of which picture had already been used and which had not.

When a book is complete (folder is emptied of images or, if not, when indicated by the user), DST announces “Congratulations, you have finished your story. Now press the blue Done button.» When the user selects the Done button, DST transitions back to the Bookshelf display, but now with the newly created video book showing on the bookshelf. From there, users simply touched their new book to initiate an automated playback routine that incorporates the selected pictures, recorded audio messages, background music soundtrack, and specialized transitioning effects to provide a high quality and compelling multimedia video story. The automated transitioning effects were custom created and included zoom in/out transitions accompanied with panning to create a sensation of movement during playback.

Results

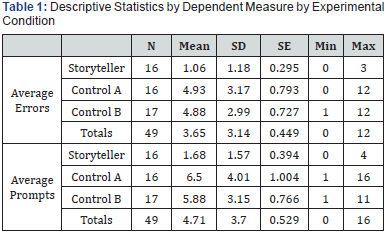

Data were analyzed using SPSS, a software package for behavioral statistics. A multivariate analysis of variance procedure was used to evaluate mean differences between the three experimental conditions (Storyteller, Control App A, and Control App B) for each dependent measure Average Errors and Average Prompts. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for each condition by dependent measure.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) yielded significant F statistics for both dependent variables (Average Errors, p <.001; Average Prompts, p<.001) measured in the pilot study. Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests were used to conduct mean comparisons for each experimental condition. The first dependent measure with a significant F value was accuracy, as measured by recording Average Errors (p<.001), which was a measure of subjects’ ability to correctly operate the three different story creation applications. Post–hoc tests were performed and for the two Control Apps. Pairwise comparisons showed no significant differences in Average Errors : Control App A (Mean = 4.88, SD= 2.99) in comparison to when subjects used Control App B (Mean = 4.93, SD= 3.17). However, when using Digital Storyteller (Mean = 1.06, SD= 1.18) subjects made significantly fewer errors when compared to Control App A (p<.001) as well as significantly fewer errors when compared to Control App B (p<.001).

ANOVA results also yielded significant overall F values for the second dependent variable, independence, as measured by Average Prompts (p<.001) provided to subjects while performing the story creation tasks during the experimental sessions. Again, Tukey’s post–hoc tests were performed. Pairwise comparisons showed no differences in average prompts when subjects used Control App A (Mean= 5.88, SD= 3.16) in comparison to when subjects used Control App B (Mean= 6.5, SD= 4.02). However, when using Digital Storyteller (Mean= 1.69, SD= 1.58) subjects required significantly fewer prompts to complete the media selection tasks as compared to when using Control App A (p=.001), and also required significantly fewer prompts as compared to when using Control App B (p<.001).

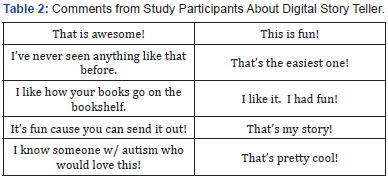

Finally, participants both reported and demonstrated their enjoyment of their success in using the Digital Storyteller system to be able to create and then playback their own stories. Several examples of statements made by test subjects in expressing their satisfaction and appreciation of the Digital Storyteller system are included in Table 2.

Discussion

The pilot study results demonstrated the technical merit and feasibility of the Digital Storyteller approach for providing a platform for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to more independently create multimedia compositions for self-expression. The pilot study provided empirical support for the contention that the Digital Storyteller system can be used by people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to create multimedia self-expression output with greater accuracy and increased independence as compared to commercially available comparison Apps. This study demonstrated the independent usability of the DST approach for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, thereby suggesting its potential to reduce or eliminate the need for proxy story telling. It was somewhat limited by the use of seeded images, and subsequent research designs that incorporate a process whereby participants obtain their own meaningful images from personal community experiences to create video stories are suggested to evaluate a variety of potential personal and social benefits.

Conclusion

The reality is that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities do have stories to tell, and multimedia tools like DST that are designed to be cognitively accessible can provide the means to enable them to share these rich and unique stories. DST and similar accessible digital supports can provide not only a means to tell stories, but a means to become part of their communities. From the wide use of social media to the myriad of ways in which self-expression can be used, Digital Story Teller and similar tools can support social inclusion, social networking, academic mainstreaming and broader community access. Furthermore, this approach provides a demonstration of how cognitively accessible technology can provide opportunities for this often too-silent population to have their voices heard and to speak for themselves.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no economic interest in or conflict of interest

References

- Kaderavek P, Rabidoux J (2004) Interactive to independent literacy: A model for designing literacy goals for children with atypical communication. Reading and Writing Quarterly 20(3): 237-260.

- Young L, Moni KB, Jobling A, Van Kraayenoord CE (2004) Literacy skills of adults with intellectual disabilities in two community-based day programs. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 51(1): 83-97.

- Fahsl AJ, Mc Andrews SL (2012) Journal writing: Support for students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and sClinic 47(4): 234-244.

- Flinchbaugh CL, Moore WG, Chang YK, May DR (2012) Student wellbeing interventions: The effects of stress management techniques and gratitude journaling in the management education classroom. Journal of Management Education 36(2): 191-219.

- Humble AM, Sharp E (2012) Shared journaling as peer support in teaching qualitative research methods. The Qualitative Report 17: 1-19.

- Shield M, Swinson K (1997) Encouraging learning in mathematics through writing. Australian Mathematics Teacher 53(1): 4-8.

- Campbell C, Deed C (2009) Engaging boys through self-reflection using an online journaling tool. Australian Educational Computing 24(1): 4-9.

- Brand AG (1979) The uses of writing in psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 19(4): 53-72

- Wright J, Man CC (2001) Mastery or mystery? Therapeutic writing: A review of the literature. British Journal of Guidance and Counseling 29(3): 277-291.

- Neuman MG (1996) The uses of writing in psychotherapy. Computers in Human Behavior 12(1): 135-143.

- Riordan RJ, White J (1996) Logs as therapeutic adjuncts in group. Journal for Specialists in Group Work 21(2): 94-100.

- Goodman G, Hart L (1988) Building communication skills. Academic Therapy 23(4): 431-435.

- Pizarro J (2004) The efficacy of art and writing therapy: Increasing positive mental health outcomes and participant retention after exposure to traumatic experience. Art Therapy 21(1): 5-12.

- Wright J (2002) Online counseling: Learning from writing therapy. British Journal of Guidance and Counseling, 30(3): 285-298

- Keeter D, Bucholz JL (2012) Group delivered literacy-based behavioral interventions for children with intellectual disability. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 47(3): 293-301.

- Paiewonsky M (2011). Hitting the reset button on education: Student reports on going to college. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals 34(1): 31-44.

- Young H, Fenwick M, Lambe L, Hogg J (2011) Multi-sensory storytelling as an aid to assisting people with profound intellectual disabilities to cope with sensitive issues: A multiple research methods analysis of engagement and outcomes. European Journal of Special Needs Education 26(2): 127-142.