Using 3-D Printed Objects to Increase Comprehension for Students with Severe Disability

Matthew James1, Jessica Besaw1, Bree Jimenez2*

1 University of North Carolina at Greensboro, North Carolina

2University of Sydney, Australia

Submission: August 22, 2018; Published: September 20, 2018

*Corresponding author: Bree Jimenez, University of Sydney, Australia, Email: drbreejimenez@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Matthew J, Jessica B, Bree J. Using 3-D Printed Objects to Increase Comprehension for Students with Severe Disability. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018; 5(2): 555658. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2018.05.555658

Abstract

Providing access to grade-level curriculum for students with severe disabilities can be challenging for teachers working on tight schedules and often with limited resources. Evidence-based practices for literacy instruction for students with severe disability include shared stories, adapted text, and the use of pictures or objects; however, not all grade appropriate texts have readily accessible objects aligned to the text. Innovative 3D printer technology can support access to a wider range of text for students with severe disability. The purpose of this case study was to investigate the use of an increasingly available technology, 3D printers, to support student understanding of fantasy literary content. 3D printed objects were found to be an effective support to increase student engagement and listening comprehension. The 3D printer technology allowed for greater access to grade-level literature, specifically improving accessibility to hard-to-come by objects and maximizing resources (time and money).

Keywords: Shared Story; 3D printed objects; Grade-level access; Literacy instruction

Introduction

Students with severe disabilities can acquire meaningful literacy skills [1,2] and those skills can directly affect an individual’s quality of life [3]. Hudson & Test [4] defined literacy as “skills that increased access to age appropriate literature.” The Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSER’s) in their Nov 16th, 2015, “Dear Colleague” letter stated that “research has demonstrated that children with disabilities who struggle in reading and mathematics can successfully learn grade-level content and make meaningful academic progress when appropriate instruction, services, and supports are provided [5].” Jorgenson [6] explained that a student’s lack of progress within the general curriculum is not reflective of the student’s ability to learn but instead the effectiveness of the instruction. Increasingly, teachers are expected to support the literacy skill development of students with severe disabilities, but ineffective instruction, lack of resources, and need for creative individualized student supports can create barriers for educators, students, and their families. This study addresses evidence-based practices that support literacy instruction, shared stories and adapted texts, for emergent readers (e.g., limited symbol use) with severe intellectual disabilities and introduces the use of newly available technology to the field of education, 3-D printers, to eliminate barriers and support student engagement and comprehension (i.e., object-based instruction).

Literature Review

Shared Stories and Adapted Text

Shared stories are found to be one of the most powerful practices in promoting understanding of various texts [4]. Shared stories are when a story is read aloud to a student by a facilitator (e.g., teacher, paraprofessional, peer model). Shared stories are especially helpful in providing access to grade level text, especially for emergent reading students [7]. In a recent literature review, Hudson & Test [4] evaluated six studies on the use of shared stories with students with severe disabilities and found a “moderate level of evidence” for incorporating shared stories into literacy lessons. Some students require extensive adaptations to the text in order to access grade-level literature [8]. Differentiating or adapting grade-level texts for students with severe disabilities can be challenging for teachers and also time consuming depending on the frequency and intensity of the text adaptations and the confidence of the text adapter. Browder et al. [9] provided access to grade-appropriate text for middle-school students with autism and moderate to severe disabilities through adapted novels (e.g., Call of the Wild). They trained teachers to read adapted novels aloud, while using a task analysis based lesson plan to teach students early literacy (e.g., title, key vocabulary) and text comprehension. For some students with severe disabilities additional adaptations (i.e., incorporation of appropriate symbol use: objects, pictures, written words) must be incorporated to provide accessibility to the curriculum content.

Object-based Instruction

Research Foundation:

There is a strong literature base for the use of objects to support listening comprehension for students with severe disabilities. Mims et al. [10] implemented the use of shared adapted stories with two students with severe intellectual disabilities and visual impairments. The authors used the adapted book, Alexander and the Terrible, No Good, Very Bad Day and incorporated objects (students held in hand) while reading the text aloud that were specific to each page (e.g., gum, candy bar) to provide the students with tangible objects associated with key information from the text. At the end of each page of the book, the facilitator then asked one comprehension question with two possible answers (one correct answer and one distractor). Results indicated that students’ text comprehension increased. Mims et al. [10] found that incorporating objects with adapted shared stories can support positive results for increasing literacy skills when working with students with severe intellectual disabilities and visual impairments.

Challenge

One challenge that educators face is that there are inherent difficulties in providing access to grade level texts for students with severe intellectual disabilities, when the shared story involves fictional settings and characters. Mims et al. [10] specifically identified everyday objects (e.g., gum, candy bar) that could be used for comprehension measures. However, locating story based objects for fantasy books like Where the Wild Things Are or Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief present challenges because of object availability, time restraints to find objects, and expense to purchase them. Many objects, specifically characters or settings, are not available at local stores. To order the objects, arrival times for the materials vary from three days to two weeks and can be costly for practitioners. One solution for this is to use 3D printer technology that has only recently become affordable and available to educators to print the objects needed for the specific story being read. For example, to order the four characters for the Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief story, online, the total cost with shipping would be roughly $52.19 and would take between seven to ten days to receive. Using a 3D model printer to create a Minotaur, Satyr, Faerie, and Percy Jackson, Figure 1, it would cost in total approximately $6 and each item takes less than one hour to print. 3D printers are increasingly more affordable and can be purchased for as little as $200, a manageable initial investment.

3D Printed Objects

Consumer-grade digital fabrication such as 3D printing is becoming more available to educators. 3D printing provides the ability to produce a 3D tangible object from a 3D model designed through a computer aided design program [11]. Objects can be printed in plastic by heating the materials to a minimum of 200 degrees Celsius [12]. The 3D objects can be chosen through a variety of 3D model repositories located online, like Thingaverse (http://www.thingiverse.com/) or can be created through programs, like Tinkercad (https://www.tinkercad.com/).

In 2014, Bueler, Comrie, Hofmann, McDonald, and Hurst explored and supported three functions for 3D printed objects in special education: i) encouraging STEM engagement; ii) supporting the creation of educational aids for providing accessible curriculum content; iii) creating custom adaptive devices. In a formative study, Bueler, et al. conducted three case studies in varying special education locations, which included interviews from therapists, educators, and administrators. Teacher interviews for future use and STEM lessons indicated that 3D printed objects can provide access to curriculum content for students with intellectual disability. Additionally, educators hoped for future access to 3D printers for all classroom teachers to provide support for students, by training other students to create the objects.

Currently, a very limited research literature base exists regarding the use of 3D printed objects for students with disability. Further, no research exists on the use of 3D printed objects to support academic instruction, specifically literacy to students with severe disabilities. The previously mentioned studies and concepts have established an evidence-based foundation of the positive effects of shared stories, text adaptations and objects, as well as provided incentive to continue exploration of the effects of 3D printed objects when teaching students with severe disability. The purpose of this study was to extend the research literature by investigating the use of innovative technology in the classroom to support literacy instruction for students with severe disability.

Target Audience and Relevance

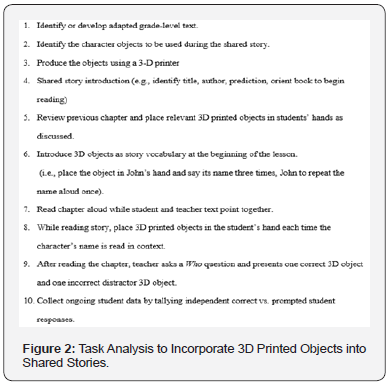

As special educators of students with severe intellectual disability continue to implement evidence-based practices within their classrooms to promote age and grade appropriate curriculum and instruction, additional research is needed to support individualized communication (receptive and expressive) needs. With such an extensive literature base on the use of shared stories, adapted text and objects usage, teachers must continue to think about how to bring all forms of literature to their students. The evidence is clear that students can and should have the opportunity to engage with a wide range of texts, including fantasy novels. The findings of this study provide an example of how technology, specifically a 3D printer, can be used to eliminate barriers within the curriculum. Educators should consider the use of 3D printing technology as another form of assistive technology to provide active student engagement. Figure 2 is provided to outline the steps of a shared story lesson with the use of 3D printed objects.

Case Study Methods

Study Design

An instrumental case study approach (i.e., looking at an issue) was implemented to examine the issue of grade-appropriate literary access using 3D printers [13]. Baseline and intervention data was collected, focusing on correct number of comprehension questions answered and the student’s level of engagement. The student also shared his opinions regarding the use of objects; a measure of social validity. Through this inductive process, we hope to embed the reader into the phenomena and through rich description of the procedures (i.e., baseline, intervention) allow other practitioners to replicate, advance, and implement the evidence-based practices [14].

Participant

One ten-year-old boy identified as having a severe intellectual disability and cerebral palsy participated in this study. Tegan was enrolled in a private separate school for students with developmental disability in the Southeastern United States. He utilized a hearing aid in one ear, along with assistive technology to communicate as needed. Tegan communicated immediate wants and needs through short one to three word phrases, pointing, and screaming when other modes are not effective. When given a choice of 2-3 objects (e.g., toys, food), Tegan was able to choose one and give it to an adult to communicate his preference. Some of Tegan’s academic IEP goals focused on the identification of the letters of the alphabet and placing numbers one through ten in sequential order. Regarding literacy lessons, therapists, teachers, and parents reported that Tegan had very little engagement with grade level novels when read aloud to him and rarely answered comprehension questions correctly. Typically, Tegan would push the book away or find something else to do when adults read grade appropriate texts to him.

Setting & Materials

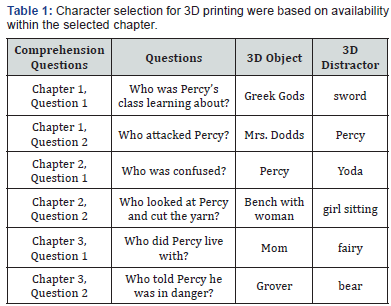

The literacy lessons for this study took place in the student’s home in the afternoon over 3 weeks’ time. Each lesson took approximately 20 minutes. Each lesson was followed by a preferred activity that the student chose and was placed on the student’s visual schedule. The adapted novel, Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief, was used. The novel was chosen because it was appropriate for fourth grade students and was often incorporated into teacher lessons about myths; included in fourth grade general curriculum standards. The novel was adapted to six or seven sentence summary chapters. This study only utilized chapters 1-3 of the novel. The summaries focused on the important themes of the chapter, leaving out additional details that do not directly affect the key points. A 3D printer, made available at a local university, was used to print objects associated with each chapter and distractor objects. The book was printed, placed in page protector sleeves and placed in a three-ring binder. Each chapter included four 3D printed objects, two characters and two distractors. Character selection for 3D printing were based on availability within the selected chapter, and effort was made to select characters that reoccurred the most frequently within the chapter. To see the specific objects used (Table 1).

Procedures

Baseline

Tegan’s baseline level responding was recorded based on his response for two comprehension questions per chapter (total of six questions across chapter one (reread three times)), as well as his engagement in the shared stories. The question difficulty was controlled for by only asking Who questions requiring direct recall from the text, in accordance with the knowledge level of Bloom’s taxonomy [15]. During baseline, the researcher introduced chapter one’s 2D laminated pictures and vocabulary and made a prediction about the story. To introduce the pictures, the researcher placed the 2D pictures in the student’s hand and repeated its name three times, then asked the student to repeat. A prediction of the book using the cover picture and title of the book followed.

The researcher then read Chapter One of the adapted text aloud and asked the student to follow along; pointing to each word of the story as she read and placing the 2D picture in the students hand each time the character was read. After completing the reading, the researcher placed two pictures, the distractor and character, in front of the student and read the predetermined question aloud once. The researcher then waited for the student’s independent response (i.e., student reaching across the table to grab the object and place it in the reader’s hand). If no response was given within ten seconds, then the researcher reread the question and waited an additional ten seconds. If no selection was made after the reread, then it was marked as incorrect response. No prompting was provided to the student if he answered incorrectly and no praise was given to correct answers. The student was thanked for answering after each selection.

Student engagement was recorded after the first two sentences of the chapter and again after the last two sentences of the chapter. Engagement was defined as the student’s participation in the lesson; visible through looking at the text, reader, images/objects, or repeating text as it is read. Baseline data on Chapter One was collected on three separate sessions following the same procedures. Once consistent baseline results were established as decelerating or zero-celerating, the 3D printed object intervention was implemented.

Intervention

Tegan’s intervention level responding was recorded based on his response for two comprehension questions per chapter (total of 12 questions across two chapters (reread three times)), as well as his engagement in the shared stories (i.e., recorded after the first two sentences of the chapter and the last two of the chapter). Each literacy lesson began with introducing the chapter objects and vocabulary, followed by a review of the previous chapter, and predicting the content of the current chapter. To introduce the objects, the researcher placed the 3D printed object in the student’s hand and repeated its name three times, then asked the student to repeat. The researcher reviewed the prior chapter with the student, then asked the student to predict what they thought the chapter would be about using objects. The researcher then read the chapter aloud to the student, asking the student to follow along.

The reader used her finger to point to each word as it was read, as well as placed the object in the student’s hand as the noun was read. After completing the reading, the researcher placed two objects, the 3D printed distractor and 3D printed character, in front of the student and read the predetermined question aloud once. The researcher then waited for the student’s independent response (i.e., student reaching across the table to grab the object and place it in the reader’s hand). If no response was given within ten seconds, the researcher would use a least-to most prompting procedure [16]. Specifically, the researcher would prompt the student towards the correct answer by repeating the question followed by, “Grab the object that answers the question and place it in my hand”. If the student answers correctly, the student is praised. If there is no response after ten seconds, a model will be provided by picking up the distractor. If no selection after ten seconds, a think aloud will be implemented, along with reaching and picking up the correct answer. If no initiation is given after ten seconds, the researcher will state the answer and place the correct object in the student’s hands. If, during any stage of the intervention, the student makes an incorrect response the researcher will attempt to block the student’s reach for the object or will immediately remove the distractor and place the correct object in the student’s hand.

Data Collection

As stated above, the number of correct independent answers and incorrect or prompted answers were recorded by the researcher. The student made their selection by pointing to, picking up or grabbing one of two pictures or objects. The researcher preplanned two questions per chapter, along with two pictures or objects per question (Table 1). Only responses that were correctly answered and unprompted were recorded as correct. Correct answers were recorded as a “+”, incorrect answers or prompted answers (e.g., verbal or model) were recorded as “-”. Student engagement was recorded at the end of the first, second, second to last, and last sentence of the paragraph. Engagement was defined as the student’s participation in the lesson; visible through looking at the text, reader, images/objects, or repeating text as it is read. When engagement was observed “+” was recorded and if it was not observed “-” was recorded.

Results

Baseline and Intervention

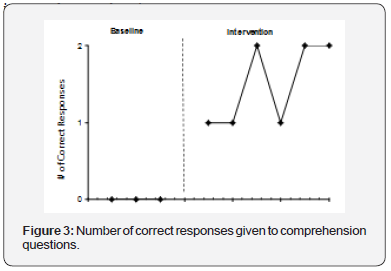

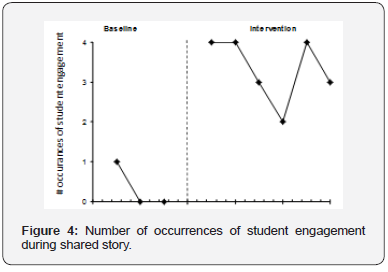

Tegan increased his overall correct responses during the duration of the study (Figure 3). During baseline, the student correctly responded to a mean of 0 comprehension questions, ranging from 0 to 0. After intervention, his correct response ranged from 1 to 2, with a mean of 1.5 out of 2. Additionally, Tegan’s engagement did increase from baseline to intervention (Figure 4). During baseline, engagement was recorded with a range of 0 to 1, with a mean of .33 out of a possible 4. After intervention, his engagement was recorded with a mean of 3.2 and a range of 2 to 4. Subsequent re-readings of the chapter potentially negatively affected engagement but may have also improved comprehension.

Social Validity

The practitioner researcher reported that she felt the incorporation of 3-D printed objects assisted the student in accessing the character content of the story, whereas in the baseline phase she felt he was less knowledgeable about the various characters due to limited engagement in the lesson. Overall, the use of 3D printed objects was beneficial, but accessibility of 3D printed items within a home environment may be less likely to occur then within a school setting. The practitioner researcher, being a former elementary school teacher, believed that she could incorporate the design, development, and presentation of the objects into typically occurring lessons within inclusive classroom contexts.

After completing the lesson, the practitioner researcher interviewed the student regarding his perception of 3D objects being incorporated into shared stories. The student smiled, grabbed his favorite character object, and said “ya” when verbally asked by the practitioner researcher if he enjoyed using the objects to answer questions. When asked which object was his favorite, he selected his preferred distractor (Yoda). Based on his response, the practitioner researcher concluded that the student was intentionally selecting an un-preferred object to answer correctly. Overall, the student demonstrated both verbal and non-verbal expressions of approval for the use of 3D printed objects.

Conclusion

The use of 3D printed objects when paired with additional evidence-based instructional strategies for teaching literacy, supported the student’s access to grade-level curriculum content. There is potential to better utilize technologies and evidence-based strategies to benefit all students across various instructional settings and contexts. For example, in an inclusive classroom, the students of the class could adapt the texts after completing graphic organizers and produce the 3D printed objects as part of science lessons; or the objects could be used as whole class attention grabbers; or as a means of developing more Universally Designed for Learning (UDL) based lessons, to maximize the learning of all students, including those with disabilities [17].

With the focus on attaining age/grade level curriculum standards, it is essential that educators use creative and flexible learning materials. Fantasy literary content may be difficult for students with severe disabilities to conceptualize. While figures and materials may be able to be bought via the internet to correspond with the fantasy text that was read aloud, the cost and time needed to search for exact replicas linked to the comprehension questions associated with the learning outcome would be time intensive and costly. Quite possibly, there may not even be replicas available for specific scenes and characters within the story; however, with the 3D printed materials, educators are able to develop and print exactly what is needed to build understanding of the story with very little cost. Therefore, the increased availability of 3-D printers empowers educators to embed the use of concrete objects into instruction, especially for hard to come by objects. The lowered costs of 3D printers, multiple functionalities and accessibility of online models encourage future utilization within the field of education. For this case, Tegan can now access a world of literature, fantasy novels, that was previously inaccessible to him.

With modern advancement of 3D printing, teachers can more effectively develop customized learning aids and individualized assistive technology supports [18]. The field of special education continues to evolve, finding new and exciting ways to support the learning and development of individuals with intellectual disability. Not too long ago, students with severe disability would not have even been exposed to age appropriate novels; however, with adapted text, shared stories and the use of pictures and objects, students have the opportunity to learn and grow; and experience the joy of literature! The 3D printer is just one more example of exciting technology that can open yet another door in the world of fantasy novels.

Acknowledgment

A special thank you to Matt Fisher and the UNC Greensboro Maker Space for their guidance and support in the printing of the 3D objects.

References

- Erickson KA, Koppenhaver DA (1995) Developing a literacy program for children with severe disabilities. Reading Teacher 48(8): 676-684.

- Ryndak DL, Morrison AP, Sommerstein L (1999) Literacy before and after inclusion in general education settings: A case study. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 24(1): 5-22.

- Browder DM, Mims PJ, Spooner F, Ahlgrim Delzell L, Lee A (2008) Teaching elementary students with multiple disabilities to participate in shared stories. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 33(1-2): 3-12.

- Hudson M, Test D (2011) Evaluating the evidence base of shared story reading to promote literacy for students with extensive support needs. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 36(1-2): 34- 45.

- Yudin MK, Musgrove M (2015) Dear colleague letter. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services, Washington, DC, USA

- Jorgenson C (2005) The least dangerous assumption: A challenge to create a new paradigm. Disability Solutions 6(3): 1-9.

- Browder D, Alhigrim Delzell L, Spooner F, Mims P, Baker J (2009) Using time delay to teach literacy to students with severe developmental disabilities. Exceptional Children 71(3): 343-364.

- Koppenhaver DA, Hendrix MP, Williams AR (2007) Toward evidencebased literacy interventions for children with severe and multiple disabilities. Semin Speech Lang 28(1): 79-89.

- Browder DM, Trela KC, Jimenez BA (2007) Training Teachers to Follow a Task Analysis to Engage Middle School Students with Moderate and Severe Developmental Disabilities in Grade-Appropriate Literature. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 22(4): 206-219.

- Mims PJ, Browder DJ, Baker JN, Lee A, Spooner F (2009) Increasing comprehension of students with significant disabilities and visual impairments during shared stories. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities 44(3): 409-420.

- Prince JD (2014) 3D printing: An industrial revolution. Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries 11(1): 39-45.

- Bridle O (2015) 3D printing and scanning: New ways to engage with students and researchers. Proceedings of the LATUL Conferences Paper 2, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

- Stake RE (2000) Case studies. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California.

- Baker C (1992) Attitudes and language (Vol 83). Multilingual Matters.

- Armstrong P (2017) Bloom’s taxonomy. Centre for teaching, Vanderbilt University: Tennessee, USA.

- Collins BC (2012) Systematic instruction for students with moderate and severe disabilities. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing: Maryland, United States.

- Rose D (2001) Universal design for learning. Journal of Special Education Technology 16(2): 66-67.

- Buehler E, Comrie N, Hofmann M, McDonald S, Hurst A (2015) Investigating the implications of 3D printing in special Education. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing 8(3): 11.