Effects of Computer-Facilitated Emotion Recognition Training for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Intellectual Disabilities

Domingo Garcia-Villamisar1*and John Dattilo2

1Department of Clinical Psychology. Complutense University of Madrid. 28040. Madrid Spain

2 Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism. The Pennsylvania State University. University Park PA 16802

Submission: July 18, 2018;; Published: August 28, 2018

*Corresponding author: Domingo Garcia-Villamisar, Department of Clinical Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid.28040, Madrid. Spain; Email Id: villasmis@edu.ucm.es

How to cite this article: Domingo Garcia-Villamisar, John Dattilo. Effects of Computer-Facilitated Emotion Recognition Training for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Intellectual Disabilities. Glob J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018; 5(2): 555656. DOI: 10.19080/GJIDD.2018.05.555656

Abstract

This study assessed effects of an emotion recognition training administered via a computer-facilitated, multimedia instructional program for adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and intellectual disabilities (ID). The intervention consisting of 410 activities was tested with a group of participants with ASD (n = 43) with a mean age 33.71 +/- 5.98 years who were divided into an experimental group (n = 22) and a control group (wait list) (n = 21). This pilot intervention study indicates that the experimental group demonstrated significant improvements in both basic and advanced emotion recognition and the control group demonstrated no such improvements. In addition, the experimental group showed indirect benefits by demonstrating a significant reduction in stress.

Keywords:Adults, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Intellectual Disability, Emotion Recognition, Computer-Facilitated

Introduction

Impairments of emotion recognition are acknowledged as prominent debilitating aspects of austism spectrum disorder (ASD) (DSM-5) [1-5]. Previous research has shown that individuals with ASD and intellectual disabilities (ID) have difficulty processing their own and other people’s emotions [6]. This impairment may result in problems with regulating social interactions, establishing reciprocal peer relationships, and/or integrating social, emotional and communicative behaviors [7,8].

Social and emotional deficits associated with ASD and IDsuch as impairments of emotion recognition negatively impact crucial areas of day-to-day functioning resulting in individuals experiencing challenges developing reciprocal peer relationships, unsuccessful leisure involvement, and an overall low quality of life [9-15]. In addition, people with ASD and ID are faced with significant barriers related to employment opportunities and workplace participation [16].Individuals with ASD and ID have difficulty identifying facial affect of other people, expressing emotions in a social context, and anticipating social consequences Bauminger&Kasar(1999) [7,17-20]. Although, there have been limited efforts to improve socio-emotional cognitive abilities of people with ASD [7,21] in the last decade a growing body of research suggests that these individuals can efficiently learn social and emotional skills by participating in intensive one-on-one educational programs[22-24]. Therefore, there is a pressing need to examine effects of instructional programs designed to enhance social and emotional skills and to examine the extent to which age and IQ influence such impairments Salomone et al. (2018).

Computer-Assisted Educational Programs

Computer-assisted educational programs may provide one method to help adults with ASD and ID learn social and emotional skills [24-27]. Such programs can be designed to: be multimodal; provide repetition, be predictable, and provide consistent procedures; require fewer social demands and include several levels of difficulty[28].Also, these computer-assisted programs can create interesting learning scenarios with animations and sounds [29]. Although effectiveness of computer-assisted educational programs have been demonstrated to promote language and vocabulary acquisition for people with ASD and ID (e.g., Smit & Sung, 2014 [30];Walen et al. 2010 [31];Yamamoto & Miya, 1999 [32]), research is needed that examines use of computer programs to teach complex socio-emotional skills [33].`

A few computer-assisted programs designed to teach complex social and emotional skills have been developed and tested. For example, Bolte et al.[34]demonstrated the usefulness of a computer program to teach participants to read facial affect; however, results failed to indicate meaningful improvements in social and cognitive skills, and generalization was not established. Also, Silver&Oakes [35] examined effects of a computer-assisted program designed to teach people with ASD to better recognize and predict emotional responses in others. The researchers demonstrated that those in the experimental group improved their emotional processing skills and these skills were generalized. Similarly, in a randomized clinical trial, Tanaka et al. (2010) implemented a computerassisted program Let’s Face It! with a group of people with ASD. Although participants demonstrated reliable improvements in their analytic recognition ofmost of the basic facial emotions, they did not demonstrate generalization of recognitions of facial emotions across different identities and showed a tendency to recognize the mouth feature holistically and the eyes as isolated parts.

Golan and Baron-Cohen [36]evaluated Mind Reading, an interactive multimedia program that teaches emotions and mental states using video, audio, and written text to introduce basic and complex emotions, and found that the group with ASD performed worse than controls on emotion recognition from faces and voices and on 12 of 20 specific emotions. The same group of researchers (Lacavaet al. [37]) used the Mind Reading program to teach emotion recognition to students with ASD and reported that students improved on face and voice emotion recognition for basic and complex emotions taught via the software. However, there was limited support for generalization of these skills to real-life contexts.Finally, Golan et al. (2010) examined effects of The Transporters, an animated series using trains with faces that interact in social scenarios to teach emotion recognition to people with ASD; however, there was limited generalization to real-life situations.

In summary, though there have been initial attempts to teach emotion recognition for individuals with ASD and ID, research examining this issue has shown limited, although positive, effect (e.g.,Bauminger [38,39]; Berggren et al. [7];Gevers et al. [40]; Hadwin et al. [41]; Golan & Baron-Cohen [36]; Ozonoff& Miller [42]; Ramdoss et al. [24]; Turner-Brown et al. [19]).Of those studies, only research by Golan and Baron-Cohen as well as Turner-Brown et al. examined effects on adults. Overall, the evidence reviewed suggests that most studies were conducted with people with average or high intelligence[43]. A strength of this study is the inclusion of people with ASD who also have ID.

ASD and Stress

The potential relationship between emotion recognition of people with ASD and comorbid psychopathologies, such as stress, is important to consider when providing services to adults with ASD.Although stress is assumed to have an important role in development and expression of challenging behavior of people with ASD[44], there is a dearth of literature examining the role of stress in the daily life of adults with ASD[45-47]. Previous research has shown that adults with ASD consistently report greater perceived stress and distress than do typical community members (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al. 2015, [44,48] which might compromise their capacity to employ cognitive strategies such as emotion recognition..

The intervention was developed to address the specific needs of adults who have ASD and ID. The aim of this study was to examine effects of a computer-assisted training program on emotion recognition skills of individuals with ASD. The main hypothesis was that the experimental group would perform significantly better on the emotion recognition posttest (including basic and dynamic visual emotion recognition, advanced complex and dynamic visual emotion recognition, and the eyes task) compared to the wait-list control group. The second hypothesis was that the experimental group would demonstrate significantly lower scores associated with stress than a wait-list control group.

Method

Participants

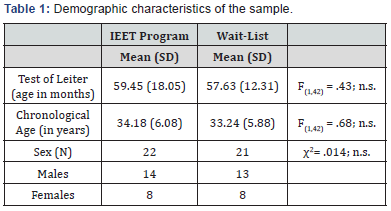

Participants were recruited from a health care facility that serves people with ASD. All of the participants have ID associated.Table 1 lists key demographic information of the sample. Participants diagnosed with ASD were matched relative to demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, severity of disability) and were randomly assigned to either an experimental group or a wait-list control group.We stratified the randomization procedure to ensure equivalence of groups on key variables such as age, gender, and severity of disability. The experimental group included 22 adults (14 males and 8 females) ages 23 to 44 (M = 34.18; Sd = 6.08); the control group included 21 adults (13 males and 8 females) ages 22 to 43 (M = 33.24; Sd = 5.88). All participants were evaluated at baseline and nine months later by a team of therapists who were blind to the research objectives.

All participants received a clinical diagnosis of ASD from a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist who each had several years of diagnostic experience with ASD. Participants were screened to exclude co-morbid neurological disorders that might influence brain functioning (e.g., dementia). Participants were excluded if they had vision worse than 20% in both eyes, if they demonstrated behaviors indicative of not comprehending the instructions for the experimental tasks, or if they did not have emotion processing deficits important enough to require intervention.

The Ethics Commission of the institution approved the research project. An explanation of the study was given to participants, their tutors, and their families before the study was initiated. All participants or their guardians provided informed consent for participation in this study.Assessments and training occurred at mental health care centers

Design and Procedures

A pre-test, post-test control group experimental design was used to measure effects of the intervention intended to facilitate improvement of emotion recognition skills of 22 adults diagnosed with ASD as compared to 21 adults with ASD who did not receive the intervention. In this report, pre- and post-treatment measures associated with emotion recognition are reported. In addition, we studied the secondary impact of the intervention on their overall stress. The 22 participants completed all intervention sessions.Members of the control group were wait-listed and, subsequently, received the intervention at the end of this study. Eligibility criteria required individuals to have emotional processing deficits. The screening of emotional processing deficits was evaluated by The Emotion Multimedia Battery Assessment for Adults with Autism (EMBAAA) described in the next paragraph.One person was excluded because the individual did not show emotional deficits.

Intervention

i. Computer-facilitated emotion recognition training.

The intervention was developed based on the work of Howlin, Baron-Cohen, and Hadwin[49]. Feedback was obtained from agency personnel and teachers during the design to increase ease of use and realism of scenarios. The intervention is comprised of two major components. The first component includes Emotion Perception Training teaching participants to recognize facial emotions from dynamic scenes; recognizing facial emotions from schematic drawings; identifying emotions linked to situations; identifying emotions linked to desires; identifying emotions linked to beliefs. The second component includes Informational States Training teaching participants to: identify that people have different opinions on the same theme, practice simple and complex visual perspective, understand that “seeing leads to knowing”[50], predict future actions on the basis of a person’s knowledge, understand true and false beliefs, and differentiate between environmental and emotional sounds.

The intervention was administered in hour-long sessions (5/week) for 36 weeks by four clinicians who were present to assist participants if they encountered difficulty operating the computer. During each session, participants were given many opportunities to identify the correct emotional expression from a range of expressions and were encouraged to consider each component of the expression in their decision-making. Participants were instructed to select the emotional expression they thought had the greatest likelihood of being correct as quickly and accurately as possible. Verbal feedback consisted of either “Correct!” “Incorrect” or “No response detected.” There is a total of 410 activities presented in this computer-based, multimedia instructional program that is compatible with the Windows XP platform.

ii. Data Collection Instruments

Autism Spectrum Disorders-Diagnosis for Adults (ASDDA) [51]. The ASD-DA is a 31-item, informant-based measure used to assess symptoms associated with ASD.The items of the ASD-DA correspond to different behavioral symptom patterns exhibited by adults with ASD and are scored 0 = not different, no impairment, or 1 = different, some impairment. A proxy respondent, a significant person in the life of the adult with ASD, completed the measure. The measure has good test–retest and inter-rater reliability, and internal consistency is robust (Cronbach’s α = .94; Matson, Wilkins, & Gonzalez, 2007; present sample, α = .89).

Stress Survey Schedule (SSS) [52].The SSS is a 49-item Stress Survey Schedule for rating perceived stress reactions and stressors experienced in the lives of people with ASD that can helpidentify circumstances that cause stress responses[53]. Grodenet al. [52] usedexploratory and confirmatory factor analysis proceduresto determine that the SSS had strong contentvalidity. Internal consistency correlations range from .70 to .87[52].In the current sample, Cronbach’s α = .86.The total score of SSS was used as an index of the global level of stress. In the current sample, Cronbach’s α = .86.

Leiter International Performance Scale (LIPS) [54]. The LIPS[54] is a non-verbal intelligence test designed for people between 2 and 18 years age, although it can be applied to all ages. No speech is required from the examiner or participant.

Emotion Multimedia Battery Assessment for Adults with Autism (EMBA-A) [55].The EMBA-AA is a multimedia battery used to assess complex and single emotions of adults with ASD. This battery was used because the adults with ASD can recognize simple emotions and pass basic theory of mind tasks, but have difficulty recognizing more complex emotions and mental state. The EMBA-AA tests recognition of a group of complex emotions and mental states from faces and voices. Most items were adapted for people whose primary language is Spanish from the English-based Cambridge Mindreading Face-Voice Battery[56]. The EMBA-AA is a set of three emotion-related experimental paradigms designed to measure biases in emotional processing thought to be core components of ASD: Basic and Dynamic Visual Emotion Recognition, The Eyes Task, and Advanced Dynamic Complex Visual Emotion Recognition.

Consistent with previous tasks, feedback is given to participants for each of their answers and their response time is measured. When a participant fails on four consecutive items, the task is terminated. This program is compatible with the Windows XP platform.The EMBA-AA was standardized with a sample of adults with ASD and the psychometric properties are identified as acceptable with a Cronbach’alfa of .79 (Author, et al. 2014)

Results

General Participant Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the sample at the beginning of the training can be seen in Table 1. No differences existed between the experimental and control group on nonverbal intelligence (Test of Leiter) (F(1,42)= .43; n.s.), chronological age (F(1,42) = .68; n.s.) and distribution by sex (χ2= .014; n.s.).

Experimental Results

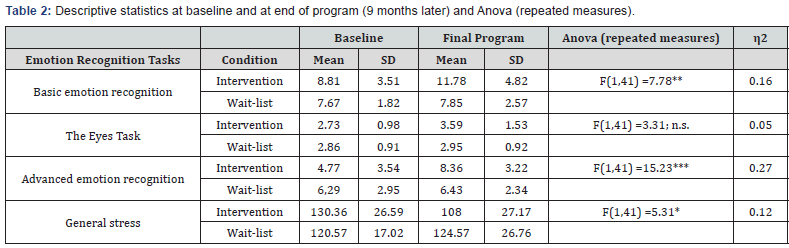

General effects of the intervention on EMBA-AA were analyzed using repeated measures Anova with pre/post scores treated as within-subject (Table 2).Related to hypothesis one, results indicated a positive interaction between group (experimental vs. wait list) and basic and dynamic visual emotion recognition (F(1,41) = 7.78; p < .01; η2= .16), and advanced complex and dynamic visual emotion recognition, First Level (F (1,41) = 15.23; p < .001; η2= .27). However, there were no differences on the Eyes task (F (1,41) = 3.31; n.s.; η2= .05).In addition, related to hypothesis two, results showed indirect benefits on general stress (F (1,41) = 5.31; p < .05; η2= .12) when the experimental group was compared to the control wit-list group.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Discussion

In relation to facial processing of emotions, results demonstrated that the intervention helped adults with ASD to recognize and identify different facial expressions. The ability to recognize and understand emotions reflected in unfamiliar faces improved for the experimental group but did not improve for the control group. More specifically, the experimental group improved their ability to recognize single and complex emotions but did not reflect such progress in recognizing emotions as expressed through people’s eyes.

Our results are similar to previous research that has obtained mixed results on facial processing of people with ASD such as the research of Beaumont and Sofronoff [57] who investigated the validity of a new multi-component social skills program for people with ASD.Results of the Beaumont and Sofronoff study indicated that relative to a control group, the experimental group showed greater progress in developing their social skills as indicted by parent and teacher-reports; however, there was no difference in the improvements made by both groups on facial expression. In another study, Golan and Baron-Cohen [36] used “Mind Reading” software to teaching individuals with high-functioning ASD to recognize emotions in voices and faces; although participant scores improved significantly on several emotion tasks (e.g., emotional concepts recognition), they did not significantly improve in generalization tasks.Soon thereafter, LaCava et al. [28] used the “Mind Reading” software to teach four youth with ASD to recognize basic and complex emotions in computer presented stimuli and demonstrated a significant improvement from pre- to post-intervention in faces and voice emotions recognition; however, effects were not strong enough to determine that the software was superior to other approaches. Finally, Silver and Oakes [35]compared the “Mind Reading” software with other technologies such as asking participants to identify emotions in cartoons and mental states occurring in stories. The authors compared results of the experimental and control group and observed large and significant effects with measures of identification of emotional and mental states; however, no significant differences were found on the facial expression naming measure.

The primary purpose of the intervention is to enhance participants’ emotion recognition; therefore, we hypothesized that the experimental group would perform significantly better on the emotion recognition post-test compared to the wait-list control group. However, a secondary purpose of the intervention was to reduce participants’ stress; therefore, we hypothesized that participants would experience an indirect reduction of stress at by the end of the intervention for the experimental group compared to the wait-list control group.

Analyses conducted to address this hypothesis indicate an indirect reduction on stress level at program termination for the experimental group. Social interactions and associated emotional responses can be stressful for adults with ASD and can result in avoidance behaviors that lead to solitary activities[53].

Several factors could explain the significant reduction of stress response in the experimental group.First, it is possible that, while a significant relationship between psychosocial stress and ASD severity has been identified in previous preliminary research due to pathognomonic emotional deficits of people with ASD[53,58,59]the enhancement of recognition and expression of emotions could contribute to a reduction of stress responses[8]. Second, the stress in adults with ASD may instead, or in addition, be caused by factors other than emotional deficits. It is possible that stress may not be intrinsically related to emotional deficits in adults with ASD and that the finding of this research about the indirect effects of the intervention program require further examination.

Given these results, the intervention may help adults with ASD and ID learn skills that increase their social and emotional functioning. The most often cited programs for enhancing emotional comprehension, such as The Emotion Trainer [35] or Mind Reading: The Interactive Guide to Emotions[56], were not developed for adults with ASD and ID[58-72]. This emotion recognition training program was designed specifically for Spanish speaking adults with ASD and ID derived from the Mind Reading software, a well-known verified program providing emotional training to people with ASD[73-88].

Limitations

Generalization is limited in this study. Since the small sample size makes it difficult to generalize results to the broader population of people with ASD and ID; we recommend future studies use a larger sample.The absence of concurrent validity of the emotion recognition training program could influence generalization of effects. It was beyond the scope of this study to examine generalization of these effects to real life. This gap is an important limitation of this study. It is recommended that further research be undertaken to analyze generalization of these effects outside the experimental context. In addition, a question that was not addressed by this study is to what degree observed effects are maintained over an extended period of time since the study lasted only nine months, a short-term follow-up period. Therefore, it would be helpful if future research included a lengthier follow-up.

Another concern of this study was that the clinicians knew the objectives of the program.In future studies, these effects should be controlled. Finally, the emotion recognition training program took a considerable length of time to implement[89-103]. It would be helpful to test shorter versions of this type of intervention to determine if a more cost-effective intervention can be developed.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the 36-week computer-assisted emotion recognition training program designed to teach emotion recognition skills to adults with ASD and ID.Overall, the experimental group’s post-test score reflected a significant improvement from their pre-training scores when compared with the wait-listed control group in their ability to recognize emotions and their perceptions of stress.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by The Royal Board on Disability (Ministry of Health and Social Policy, Spain) and The Social Policy Department (Regional Govern of Madrid, Spain). The authors gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Francisco Herranz of Talent Group on the technological design of the programs. We appreciate the assistance of Ainara Buren, Carmen Muela and Marina Jodra with the administration and organization of the data set and the participants’ teachers who contributed to the development of the program and assisted with data collection. Finally, and most importantly, we thank the program participants for their involvement.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.) Washington, DC, USA.

- Baron Cohen S, Wheelwright S (2003) The friendship questionnaire: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev Disord 33(5): 509– 517.

- Charman T, Jones CR, Pickles A, Simonoff E, Baird G, et al. (2011) Defining the cognitive phenotype of autism. Brain Res 1380: 10-21.

- de Vries M, Geurts HM (2012) Cognitive flexibility in ASD; Task switching with emotional faces. J Autism Dev Disord 42(12): 2558- 2568.

- Griffiths S, Jarrold C, Penton Voak IS, Woods AT, Skinner AL, et al. (2017) Impaired recognition of basic emotions from facial expressions in young people with autism spectrum disorder: Assessing the importance of expression intensity. J Autism Dev Disord 48: 1-11.

- Samson AC, Huber O, Gross JJ (2012) Emotion regulation in Asperger’s syndrome and high-functioning autism. Emotion, 12(4): 659-665.

- Berggren S, Fletcher Watson S, Milenkovic N, Marschik PB, Bölte S, et al. (2018) Emotion recognition training in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of challenges related to generalizability. Developmental Neurorehabilitation 21(3): 141-154.

- Ke F, Whalon K, Yun J (2017) Social skill interventions for youth and adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research 88(1): 3-42

- Garcia Villamisar DA, Dattilo J (2010) Effects of a leisure program on quality of life and stress of individuals with ASD. J Intellect Disabil Res 54(7): 611-619.

- Garci Villamisar D, Hughes C (2007) Supported employment improves cognitive performance in adults with Autism. J Intellect Disabil Res 51(Pt 2): 142-150.

- Magiati I, Tay XW, Howlin P (2014) Cognitive, language, social and behavioural outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review of longitudinal follow-up studies in adulthood. Clin Psychol Rev 34(1): 73-86.

- Orsmond GI, Kuo HY (2011) The daily lives of adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder: discretionary time use and activity partners. Autism 15(5): 579-599.

- Pellicano E (2012) Atypical social cognition. In Fiske S & Macrae N (Eds.) Sage handbook of social cognition (pp. 411 – 428). Sage, London, UK

- Sterzing PR, Shattuck PT, Narendorf SC, Wagner M, Cooper BP (2012) Bullying involvement and autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and correlates of bullying involvement among adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 166(11): 1058-1064.

- Taylor JL, Mc Pheeters ML, Sathe NA, Dove D, Veenstra Vanderweele, et al. (2012) A systematic review of vocational interventions for young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 130(3): 531-538.

- Walsh E, Holloway J, Lydon H (2018) An evaluation of a social skills intervention for adults with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities preparing for employment in Ireland: A Pilot Study. J Autism Dev Disord, 48(5): 1727-1741

- Begeer S, Rieffe C, Terwogt MM, Stockmann L (2006) Attention to facial emotion expressions in children with autism. Autism, 10(1): 37–51.

- Deruelle C, Rondan C, Gepner B Tardif C (2004) Spatial frequency and face processing in children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 34(2): 199–210.

- Turner Brown LM, Perry TD, Dichter GS, Bodfish JW, Penn DL (2008) Brief report: feasibility of social cognition and interaction training for adults with high functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 38(9): 1777- 1784.

- Salomone E, Kutlu B, Derbyshire K, McCloy C, Hastings RP, et al. (2014) Emotional and behavioural problems in children and young people with autism spectrum disorder in specialist autism schools. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 8(6): 661-668.

- Ryan C, Charragain CN (2010) Teaching emotion recognition skills to children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 40: 1505–1511

- Benyakorn S, Calub CA, Riley SJ, Schneider A, Iosif AM, et al. (2018) Computerized cognitive training in children with autism and intellectual disabilities: Feasibility and satisfaction study. JMIR Mental Health 5(2): e40.

- Kasari C, Patterson S (2012) Interventions addressing social impairment in autism. Current Psychiatry Reports 14(6): 713-25.

- Ramdoss S, Machalicek W, Rispoli M, Mulloy A, Lang R, et al. (2012). Computer-based interventions to improve social and emotional skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitaton 15(2): 119-135.

- Stauch TA, Plavnick JB, Sankar S, Gallagher AC (2018) Teaching social perception skills to adolescents with autism and intellectual disabilities using video‐based group instruction. J Appl Behav Anal 51(3): 647-674.

- Wainer AL, Ingersoll BR (2011) The use of innovative computer technology for teaching social communication to individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 5(1): 96-107.

- White SW, Richey JA, Gracanin D, Coffman M, Elias R, et al. (2016) Psychosocial and computer-assisted intervention for college students with autism spectrum disorder: Preliminary support for feasibility. Educ Train Autism Dev Disabil 51(3): 307-317.

- Golan O, LaCava PG, Baron Cohen S (2007) Assistive technology as an aid in reducing social impairments in autism. In Gabriels RL, Hill DE (Ed.) Growing Up with Autism: Working with School-Age Children and Adolescents, (pp. 124-142). The Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Calvert S L, Watson JA, Brinkley V, Penny J (1990) Computer presentational features for poor readers’ recall of information. Journal of Educational Computing Research 6(3): 287–298.

- Smith V, Sung A (2014) Computer Interventions for ASD. In Patel VB, Preedy VR, Martin CR (Eds.), Comprehensive guide to Autism (pp. 2173–2189). Springer, Berlin, Germany

- Whalen C, Moss D, Ilan AB, Vaupel M, Fielding P, et al. (2010) Efficacy of TeachTown: Basics computer-assisted intervention for the intensive comprehensive autism program in Los Angeles unified school district. Autism 14(3): 179–197

- Yamamoto J, Miya T (1999) Acquisition and transfer of sentence construction in autistic students: Analysis by computer based teaching. Research in Developmental Disabilities 20(5): 355–377.

- Rice LM, Wall CA, Fogel A, Shic F (2015). Computer-assisted face processing instruction improves emotion recognition, mentalizing, and social skills in students with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord 45(7), 2176-2186.

- Bölte S, Feineis Matthews S, Leber S, Dierks T, Hubl D, et al. (2002) The development and evaluation of a computer-based program to test and to teach the recognition of facial affect. Int J Circumpolar Health 61(2): 61-8.

- Silver M, Oakes P (2001) Evaluation of a new computer intervention to teach people with autism or Asperger syndrome to recognize and predict emotions in others. Autism 5(3): 299-316.

- Golan O, Baron Cohen S, Hill J (2006) The Cambridge Mindreading (CAM) Face-Voice Battery: Testing complex emotion recognition in adults with and without Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 36(2): 169-183.

- La Cava PG, Golan O, Baron Cohen S, Myles BS (2007). Using assistive technology to teach emotion recognition to students with asperger syndrome a pilot study. Remedial and Special Education 28(3): 174- 181.

- Bauminger N (2002) The facilitation of social-emotional understanding and social interaction in high functioning children with autism: Intervention outcomes Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 32(4): 283–298.

- Bauminger N (2007) Brief report: group social-multimodal intervention for HFASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 37(8): 1605-1615.

- Gevers C, Clifford P, Mager M, Boer F (2006) Brief report: A theoryof- mind-based social-cognition training program for school-aged children with pervasive developmental disorders: An open study of its effectiveness. J Autism Dev Disord. 36(4): 567-571.

- Hadwin J, Baron Cohen S, Howlin P, Hill K (1997) Does teaching theory of mind have an effect on the ability to develop conversation in children with autism? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 27(5): 519–537.

- Ozonoff S, Miller JN (1995) Teaching theory of mind: a new approach to social skills training for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 25(4): 415-433.

- Harms MB, Martin A, Wallace GL (2010) Facial emotion recognition in autism spectrum disorders: a review of behavioral and neuroimaging studies. Neuropsycholo Rev 20(3): 290-322

- Hirvikoski T (2014). High self-perceived stress and poor coping in intellectually able adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 19(6): 752-757.

- Baron MG, Groden J, Froden G, Lipsitt LP(2006) Stress and coping with autism. Oxford University Press: New York, USA.

- Chalfant AM (2011) Managing anxiety in people with autism. Woodbine Houses: North Bethesda, Maryland.

- García Villamisar D, Rojahn J (2015) Comorbid psychopathology and stress mediate the relationship between autistic traits and repetitive behaviours in adults with autism. J Intellect Disabil Res 59(2): 116- 124.

- Bishop Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Mazefsky CA, Eack SM (2016) Perception of life as stressful, not biological response to stress, is associated with greater social disability in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 47(1): 1-16.

- Howlin P, Baron Cohen S, Hadwin J, Swettenham J (1999) Teaching children with autism to mind-read. Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA.

- Baron Cohen S, Goodhart F (1994) The seeing leads to knowing” deficit in autism: the Pratt and Bryant probe. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 12(3): 397–402

- Matson JL, Boisjoli JA (2008) Autism spectrum disorders in adults with intellectual disability and comorbid psychopathology: Scale development and reliability of the ASD-CA. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2(2): 276-287.

- Groden J, Diller A, Bausman M, Velicer W, Norman G, et al. (2001) The development of a stress survey schedule for persons with autism and other developmental disabilities. J Autism Dev Disord 31(2): 207-217.

- Groden J, Baron MG, Groden G (2006) Assessment and coping strategies. In Baron MG, Groden J, Groden G, Lipsitt LP. Stress and coping in autism (pp. 15–41). Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Leiter RG (1980) Leiter International Performance Scale, instruction manual. Stoelting: Chicago, llinois, USA.

- Garcia Villamisar, Muela C, Jodra M (2014b) Emotion Multimedia Battery Assessment for Adults with Autism. CERSA Edit: Madrid, Spain

- Baron Cohen S (2004) Mind reading emotions library. The interactive guide to emotions. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, USA.

- Beaumont R, Sofronoff K (2008) A multi-component social skills intervention for children with Asperger syndrome: The Junior Detective Training Program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 49(7): 743-753.

- Olsson NC, Flygare O, Coco C, Görling A, Råde A, et al. (2017) Social skills training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56(7): 585-592

- South M, Rodgers J (2017) Sensory, emotional and cognitive contributions to anxiety in autism spectrum disorders. Front Hum Neurosci 11(20)

- Ashwin C, Baron Cohen S, Wheelwright S, O’Riordan M, Bullmore ET (2007) Differential activation of the amygdala and the ‘social brain’ during fearful face-processing in Asperger Syndrome. Neuropsychologia 45(1): 2-14.

- Baron Cohen S (2011) Zero degrees of empathy: A new theory of human cruelty. Penguin/Allen Lane: London, USA.

- Baron Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill JJ, Raste Y, Plumb I (2001) The Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol. Psychiat 42(2): 241–251.

- Bossler A, Massaro DW (2003) Development and Evaluation of a Computer-Animated Tutor for Vocabulary and Language Learning in Children with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 33(6): 653-672.

- Burguess PW, Alderman N, Evans J, Emslie H, Wilson BA (1998) The ecological validity of tests of executive function. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 4: 547–558.

- Caballo C, Crespo C, Jenaro C, Verdugo MA, Martinez JL (2005) Factor structure of the Schalock and Keith Quality of life Questionnaire (QOL-Q): Validation on Mexican and Spanish samples. J Intellect Disabil Res 49: 773-776.

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.) Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, New Jersey.

- Dziobek I, Bahnemann M, Convit A, Heekeren HR (2010) The role of the fusiform-amygdala system in the pathophysiology of autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(4): 397-405.

- Elzouki SY, Cooper B Moore (2012) Understanding and enhancing emotional literacy in children with severe autism using facial recognition software. In Moore D, Gorra A, Adams M et al. Disabled students in education: Technology, transition, and inclusivity (pp 107- 128). IGI Global: Hershey PA, Pennsylvania

- Fombonne E (2009) Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Res 65(6): 591-598.

- Frith U, Frith CD (2003) Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 358(1413): 459–473.

- Frith U, Happé F (1994) Autism-beyond theory of mind. Cognition 50(1-3): 115–132

- Garcia Villamisar, Muela C, Jodra M (2014a) The Interactive Emotional Enhancement Training. CERSA Edit: Madrid, Spain

- Geurts HM, Vissers ME (2012) Elderly with autism: executive functions and memory. J Autism Dev Disord 42(5): 665-675

- Gillberg C, Billstedt E (2000) Autism and Asperger syndrome: coexistence with other clinical disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 102(5): 321-330.

- Gillott A, Standen PJ (2007) Levels of anxiety and sources of stress in adults with autism. J Intellect Disabil 11(4): 359-370.

- Howlin P, Baron Cohen S, Hadwin J, Swettenham J (1999) Teaching children with autism to mind-read. Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA.

- Howlin P, Moss P (2012) Adults with autism spectrum disorders. Can J Psychiatry, 57(5): 275-283.

- Jazaieri H, Urry HL, Gross JJ (2013) Affective disturbance and psychopathology: An emotion regulation perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology 4(5): 584-599.

- Kennedy DP, Adolphs R (2012) Perception of emotions from facial expressions in high-functioning adults with autism. Neuropsychologia 50(14): 3313-3319.

- Lockwood PL, Bird G, Bridge M, Viding E (2013) Dissecting empathy: high levels of psychopathic and autistic traits are characterized by difficulties in different social information processing domains. Front Hum Neurosci 7: 760.

- Mannion A, Leader G (2013) Comorbidity in autism spectrum disorder: A literature review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 7(12): 1595-1616.

- Matson JL, Cervantes PE (2014) Commonly studied comorbid psychopathologies among persons with autism spectrum disorder. Res Dev Disabil 35(5): 952-962.

- Matson JL, Boisjoli JA, Gonzalez ML, Smith KR, Wilkins J (2007) Norms and cut-off scores for the Autism Spectrum Disorders Diagnosis for Adults with Intellectual Disability. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 1(4): 330–338.

- Matson JL, Wilkins J, Gonzalez M (2007) Reliability and factor structure of the autism spectrum disorders-diagnosis scale for intellectually disabled adults (ASD-DA). Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 19: 565–577.

- Matson JL, Wilkins J, Boisjoli JA, Smith KR (2008) The validity of the Autism Spectrum Disorders-Diagnosis for intellectually disabled adults (ASD-DA). Res Dev Disabil 29: 537–546.

- Matthews G, Zeidner M, Roberts RD (2017) Emotional intelligence, health, and stress. In CL Cooper & JC Quick (Eds.). The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice (pp. 312-326). John Wiley and Sons: West Sussex, UK.

- Mazza M, Pino MC, Mariano M, Tempesta D, Ferrara M, et al. (2014) Affective and cognitive empathy in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Front Hum Neurosci 8: 791-797.

- Montgomery CB, Allison C, Lai MC, Cassidy S, Langdon PE et al. (2016) Do adults with high functioning autism or Asperger Syndrome differ in empathy and emotion recognition? J Autism Dev Disord 46(6): 1931- 1940.

- Ozonoff S, Miller JN (1995) Teaching theory of mind: a new approach to social skills training for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(4): 415-433.

- Renwick R & Friefeld S (1996) Quality of life and rehabilitation. In R Renwick I Brown & M Nagler (Eds.) Quality of life in health promotion and rehabilitation: Conceptual approaches, issues and applications (pp. 26–38) CA: Sage, California, United States.

- Renwick R, Fudge Schormans A & Zekovic B (2003) Quality of life for children with developmental disabilities: a new conceptual framework. Journal on Developmental Disabilities 10: 107–114

- Richey JA, Damiano CR, Sabatino A, Rittenberg A, Petty C, et al. (2015) Neural Mechanisms of Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord.45(11): 3409-3423.

- Rodger H, Vizioli L, Ouyang X, Caldara R (2015) Mapping the development of facial expression recognition. Developmental Science, 18(6): 926-939.

- Rojahn J, Esbensen AJ, Hoch TA (2006) Relationships between facial discrimination and social adjustment in mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Retardation 111(5): 366–377.

- Samson AC, Hardan AY, Lee IA, Phillips JM, Gross JJ (2015) Maladaptive behavior in autism spectrum disorder: The role of emotion experience and emotion regulation. J Autism Dev Disord 45(11): 3424-3432

- Schalock RL, Keith KD (1993) Quality of Life Questionnaire Manual. IDS Publishing: Worthington, Ohio, United States

- Spain D, Harwood L, O Neill L (2015) Psychological interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders: a review. Advances in Autism 1(2): 79-86.

- Tanaka JW, Wolf JM, Klaiman C, Koenig K, Cockburn J, et al. (2012) The perception and identification of facial emotions in individuals with autism spectrum disorders using the Let’s Face It! Emotion Skills Battery. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 53(12): 1259- 1267.

- Thomas LA, De Bellis MD, Graham R, La Bar KS (2007) Development of emotional facial recognition in late childhood and adolescence. Dev Sci 10(5): 547-558.

- Uljarevic M, Hamilton A (2013) Recognition of emotions in autism: a formal meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 43(7): 1517-1526.

- Van Heijst BF, Geurts HM (2014) Quality of life in autism across the lifespan: A meta-analysis. Autism 19(2): 158-167

- Wallace S, Sebastian C, Pellicano E, Parr J, Bailey A (2010) Face processing abilities in relatives of individuals with ASD. Autism Research 3(6): 345-349.

- Zaki J, Ochsner KN (2012) The neuroscience of empathy: progress, pitfalls and promise. Nat Neurosci 15(5): 675–680.