French Guiana, Patterns of Growth and Development

Paul Rosele Chim*

HDR in Economics and Management & Teach-Researcher, MINEA UR 7485 University of French Guiana, French Guiana

Submission: June 06, 2020; Published: July 13, 2020

*Corresponding author: Paul Rosele Chim, HDR in Economics and Management-University of Paris Pantheon Sorbonne, Teach-Researcher MINEA UR 7485 University of French Guiana, French Guianaa

How to cite this article:Paul R C. French Guiana, Patterns of Growth and Development. Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud. 2020; 5(4): 555669. DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555669

Abstract

French Guiana represents the largest territory of any region in France. Still, in 2019 its population came to just 296,847. In recent years the economy, while showing positive signs, has faced several significant challenges. The factors associated with growth and development in French Guiana are examined in detail in this chapter with particular emphasis given to the short-term period from 2000–10 and the long-term growth path from 2000–17. Given the dearth of relevant data in the English literature, much of the discussion is confined to documenting the economy’s movements over these periods.

Keywords: Economic; Growth; Mining; History; Geographic; Coastal areas; Labour market; Forestry

Introduction

Historically, French Guiana’s growth and development suffered from poor geographic location, deficient infrastructure away from coastal areas, and an absence of critical labour force skills. These deficiencies have all limited the development of critically important agricultural, mining, forestry, fishing and tourism sectors. Currently, the mismatch between supply and demand remains a significant feature of the labour market. While the unemployment rate has fallen in recent years with salaried employment on the increase, the youth unemployment rate remains high at slightly over 30% despite the government’s attempts to improve education and training. The major optimistic sign is the uptick in space activity. The European Space Agency’s (ESA) satellite launching centre at Kourou, Arianespace, continues to expand and represents a significant element of the economy, generating approximately 15% of French Guiana’s gross domestic product (GDP). In 2018 ESA was responsible for approximately 4,620 direct jobs and, in total, accounted for 9.3% of salaried workers. The centre concluded 20 new contracts in 2015 for future launches that are anticipated to generate €2,500 million. A significant expansion programme, Ariane 6, was expected to be operational by 2023. However, structural obstacles persist [1-5]. The first involves the imbalance between the growth of collective needs and the provision of public services, and the second, a private sector that is both underdeveloped and insufficiently diversified. In addition to these two characteristics, there are also several unfavorable cyclical phenomena leading to difficulties in many of the traditional sectors. Prime examples include fishing (mainly shrimp), which suffers from high operating costs and unstable external markets. For similar reasons, agri-food exports remain weak. The vital gold sector suffers from illegal mining and volatile prices, while domestic air transport is experiencing disruptions resulting in a significant decline in tourism activity. Other problem areas include excessive government deficits financed by bank credit, excessive governmental interference in the economy, and protectionism that increases the costs of local production. There is considerable intervention on the part of the territorial communities of French Guiana, the municipalities and the urban agglomerations. These interventions cushion difficulties by helping to maintain activities and limit social tensions. Public procurement thus plays a leading role, particularly in sectors such as construction (buildings and public works). Salaries paid to civil servants in the state, local authorities, and the hospital civil service have provided stimuli to a variety of sectors, including those in the trade, catering and services. They have also stimulated business start-ups with 900 new companies registered since 2001. Government salaries and procurement have created an environment in which household consumption dominates the economy [6-10].

Short-term economic patterns (2000-20)

The following sections shed light on French Guiana’s pattern of development and the imbalances incurred. The lack of relevant data hinders this effort, yet several developments reflect the underlying currents. During the period 2000–10, there was severe social unrest and weak growth of 1.5% in 2001 following the collapse of sugar, rice, gold and especially bauxite exports. As a result of the downturn and associated financial and debt crisis, the authorities had to enter into an agreement with the International Monetary Fund. A severe decline in tourism in 2003 further compounded the crisis. From 2000–10 foreign trade showed an increase in value with the trade coverage rate ranging from 19.6% to 21.2%. On average, during the period the five main exports were gold (around €82 million), fishery products (€17 million), rice (€5 million), measuring instruments (€3.8 million) and sawn timber (€2.5 million). These products represented 85% of exports. The gold sector accounted for 63% of exports. Metropolitan France remained the leading market. The Netherlands Antilles and Brazil were the second and third largest markets, respectively, with the USA fourth. Exports of agriculture and fisheries declined during this period, with the increase in citrus fruit not compensating for the collapse of fisheries and aquaculture. Only Guadeloupe, French Guiana’s third largest customer of these products, increased its imports (by 21%), while metropolitan France and Martinique decreased theirs by around 37% and 11%, respectively. Although exports of rice (33%) and rum (35%) increased, their small volumes were not enough to offset the decline in other areas. As a result, the agri-food sector experienced an export decline of 5%. There were some bright spots, however. During this period Spain became an important customer of rice as did Colombia (2% of exports). Other areas such as footwear (97%), pharmaceuticals (53%) and domestic appliances (85%) experienced significant export declines. However, communication equipment grew by 12%, but not enough to offset the collapse in demand from Martinique.

During this period imports came mainly from Trinidad and Tobago, and Martinique. Intermediate goods represented 12% of imports with metallurgical products and textiles accounting for approximately 21% and 9%, respectively. Imports of consumer goods increased in value with relatively stable quantities. The most substantial growth occurred in optical and photographic equipment (36%) and clothing (22%). On average, during this period the trade balance was in deficit (€532 million) with imports at €660 million and exports (€128 million). Also, during this period most financial assets were held by individuals (65%). The balance accrued to companies, government entities and insurance companies. Deposits collected by credit institutions amounted to approximately €694 million, with growth during this period at nearly 11% per annum. Savings in French Guiana averaged approximately €349 million, or 50.2% of assets. Shortterm and liquid investments amounted to €211 million, or 30.4%. Liquid investments consisted mainly of passbook accounts (61%) and long-term deposits (20%). Long-term savings averaged €134 million, or less than 20% of all assets. The data suggest that financial markets in French Guiana were underdeveloped at this time with the Institut d’émission des départements d’outre-mer (IEDOM) indicating that the cost of credit remained high throughout the period with the overall weighted average rate for companies at 8.89%. However, during this period banks remained highly profitable, with net banking income increasing at 17% despite the amount of credit granted remaining low. French Guiana’s public finances during this period were relatively underdeveloped. The total amount of tax revenue collected from households and businesses averaged €330 million. These revenues came from direct taxation and local taxation, with the latter affecting both households and businesses, namely housing taxes, business taxes and revenues from developed property. Indirect tax revenues were mainly those received from dock dues and averaged €98.5 million. However, fuel tax revenues fluctuated considerably due to volatile world oil markets.

During this period tax revenues were generally in line with the structure of the economy, with an over-reliance on revenues derived from consumption and imports. For the most part, tax revenues financed local authorities, with municipalities receiving, on average, about €59 million in indirect taxes. On the expenditure side, population growth played a significant role during this period with French Guiana facing structural constraints brought on by rapidly growing collective needs. State and local governments spent, on average, €1,179 billion. The state’s operating expenses averaged around €108 million, with equipment accounting for 21%, defence 18%, and education 16%. National capital expenditure (direct and equipment subsidies) remained at an average level of €91.8 million with direct investments representing between €24.5 and €28.5 million. Government personnel costs averaged between €255 million and €268 million. With a total amount of €560 million, the public sector played an essential role in the economy. During this period a limited number of activities dominated the economy. Fishing occupied third place in exports after space industry activities and gold mining. On average, fishing generated €19.6 million in export revenues, with the shrimping port of Larivot remaining one of the leading French fishing ports. In 2003 shrimp production reached 3,557 metric tons, following two years of low production of around 2,600 tons. Production peaked at 4,000 tons in 1986. On average, production per boat/year was 65 tons – the highest in the French Guiana-Brazilian zone with Amapa and Suriname fleets averaging 35 to 45 tons per boat. The biggest problem faced by the French Guiana fleet was that of illegal fishing. Red snapper fishing was carried out in French Guiana by handline from 41 Venezuelan vessels under European licence. However, due to over-fishing production fell after 1998 [12-13]. From 1998 production and fishing efforts decreased, allowing the fishery to recover. In 2003 landed production in French Guiana was 862 metric tons. However, the average weight of fish decreased from 1.0 kg to 750 grams. In 2002 the volume exported was 734 tons and generated €2.7 million. This Figure compares with around 1,481 tons or €6 million in 1998. Whitefish is another important species for commercial fishing in French Guiana and includes all species of fish other than snappers. In French Guiana’s case, this includes mainly machoirans, acoupas, croupias, rays and sharks. Fishing for this species involves a professional sector with registered ships and an informal sector operated by lower-income individuals. A variety of fishing techniques are utilized, including straight net, set net, longlines, trolling line, and rod techniques.

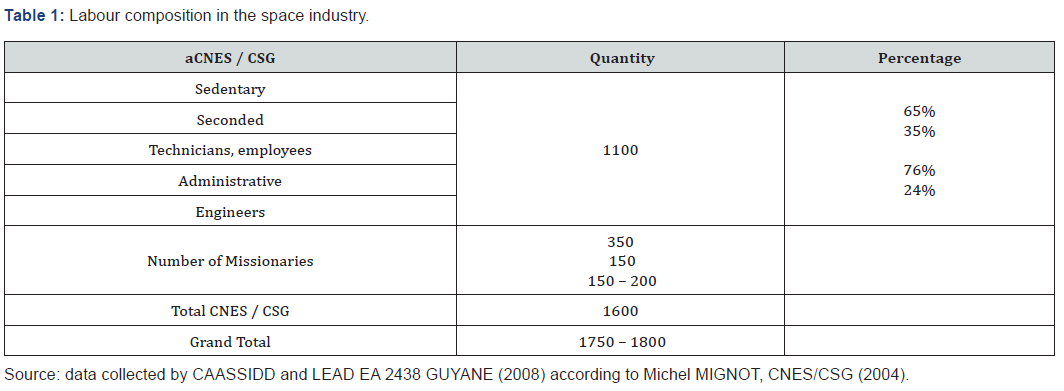

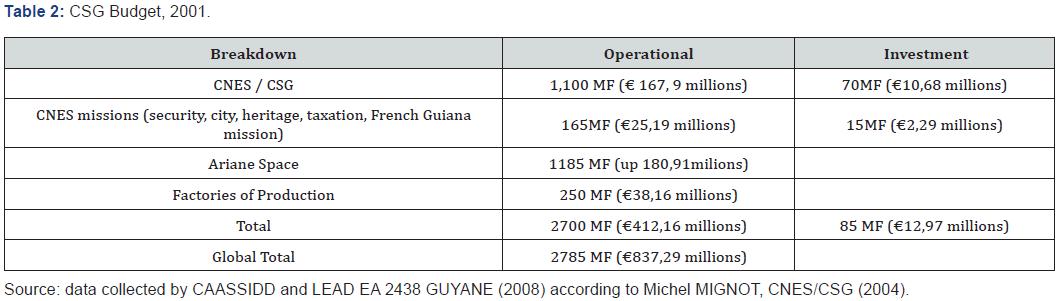

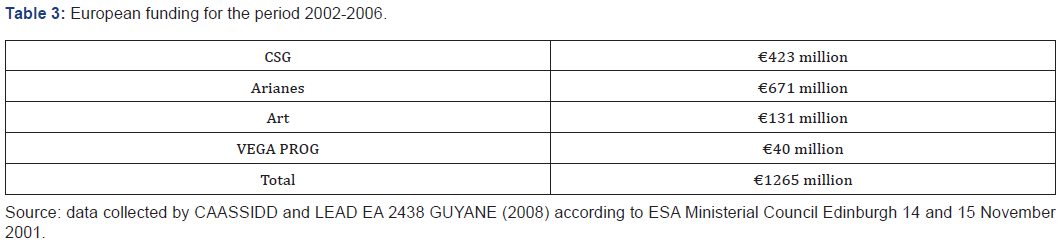

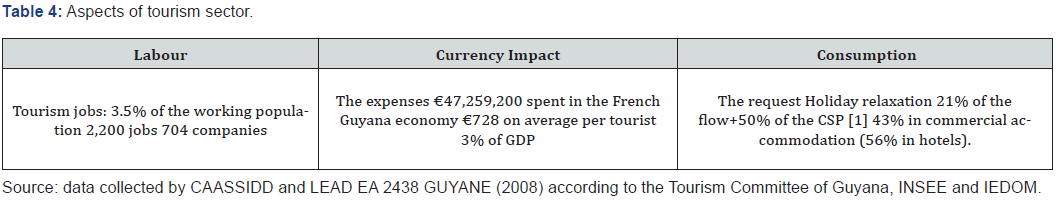

According to the evolution of the snapper fishery from 1988 to 2006, based on the author’s compilation, the whitefish sector represents, on average, between 2,000 and 3,500 tons of fish peryear. It averaged about 100 boats with a minimum of 209 sailors registered on board. Despite its inefficiency and poor organization, the sector has the potential for a significant expansion in output and employment. Construction represented a significant segment of the economy, with public procurement being the driving force. Housing construction underwent a significant expansion with a shift towards that already taking place in the municipalities. In this regard, local authorities gradually assumed a more critical role. On average, the private sector accounted for 33% of housing starts. Expansion in non-residential buildings (shopping centres, space industry buildings) also occurred. Several indicators of construction, such as sales of bagged cement, which increased to 6% and in roofing sheet expanding by 3% paint a picture of slow growth (2003). However, in contrast, building permits for the public sector increased by 34%, and those for the private sector by 62%. In any case, the imbalance between the supply and demand for housing remained high, with an average waiting time of 20 months to obtain housing. In part, the gap between demand and supply for housing stemmed from a severe shortage of skilled labour in the building trades. Overall, in 2004 construction contributed €360 million or 15% of GDP. At this time, the sector employed 2,500 workers in the formal sector and 1,600 in the informal sector. There were also 800 craftsmen and small business owners, and 500 temporary workers. In 2004 public procurement accounted for 66% of construction activity compared to only 37% in metropolitan France. Construction activity picked up considerably in 2006 with value added increasing by 27%. At this time, the driving force expanding construction was the activity related to the preparation of the new Soyuz and Vega space ports. This stepped-up activity involved the hiring of 500 additional employees at the end of 2007. Expenditure on these programmes amounted to approximately €160 million. Air transport represents another segment of the economy, although its contribution has been affected significantly by international, national and regional cyclical phenomena. During this period these included the structure of the global economy marked by an upward trend in oil prices and the global recession. Furthermore, the small size of the regional market created a disincentive for diversification with less than 400,000 passengers per year limiting profitability. During this period French Guiana ports averaged 644,000 metric tons of goods. In terms of volume, the main items moved through the ports involved hydrocarbons with rice exports also a valuable item. On average, 3,900 new vehicles were imported. The space industry made a significant contribution to economic activity during this period, employing between 1,750 and 1,800 workers (Table 1). The industry’s budget (Table 2 & 3) was one of the largest in French Guiana. Tourism represents another important sector (Table 4). During this period the government attempted to expand tourism with the 2000–06 State-Region Plan Contract indicating a renewed commitment to making tourism one of the critical areas of economic development. In the past, many tourism operators had avoided French Guiana owing to disruptions on domestic routes. The main thrust of the State-Region Plan was a large-scale publicity effort (valued at €1 million per year) designed to enhance French Guiana’s image as a tourist destination. Its goal was to increase the annual flow of tourists to 100,000. Unfortunately, the programme was not successful and tourist activity deteriorated by 13% in 2006, with the hotel occupancy rate remaining at 52%. Tourist spending fell by 2% in 2007 [13-15].

Growth and development in the long term (2000–18)

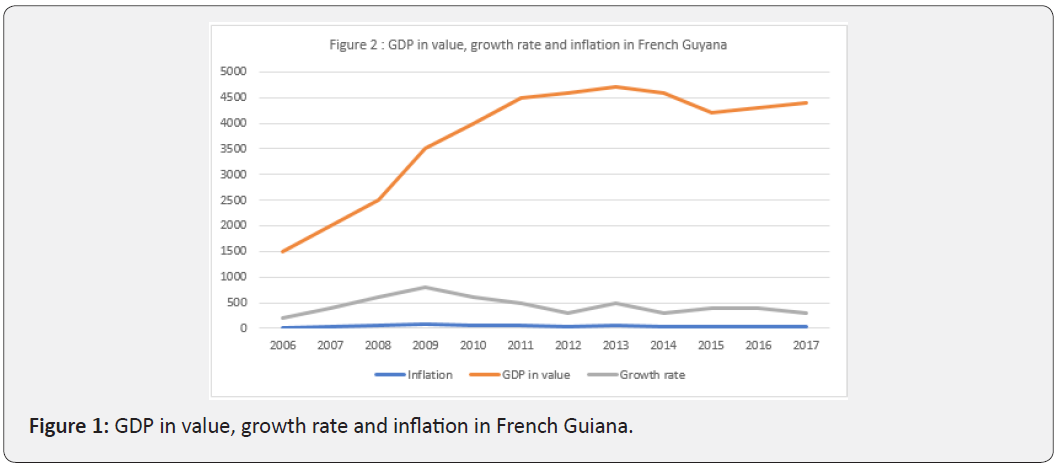

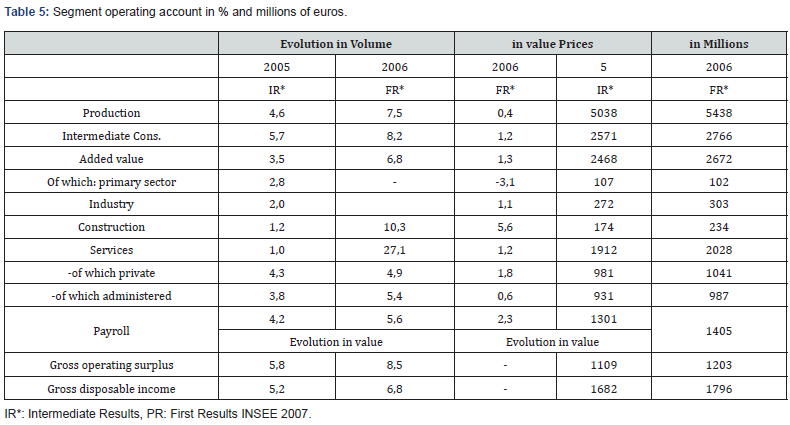

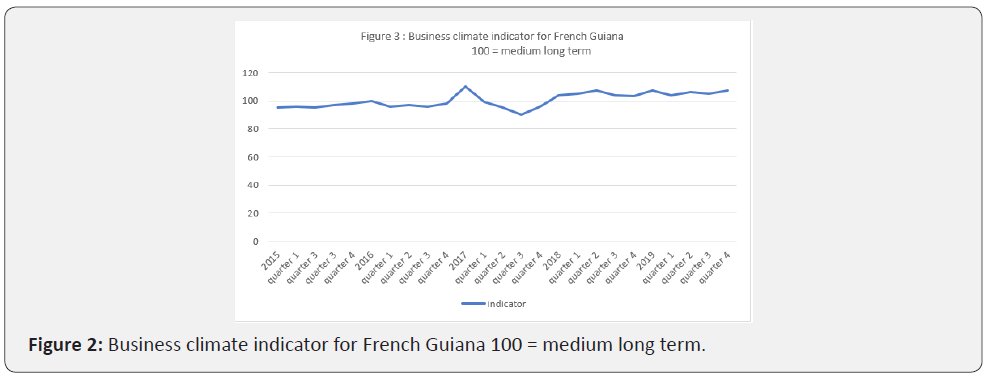

The TABLO-Guyana model, a Keynesian quasi-accounting model, can be utilized to identify longer-term trends in the economy1. The model incorporates several underlying assumptions concerning the evolution of the supply and demand for goods and services. The model consists of 25 branches and 25 products. The results for the period 2000–10 are presented in Table 5. In 2006 it was estimated that the French Guiana economy grew by 6.4% in terms of volume. CEROM’s estimates showed that the economy grew by 3.6% in the previous year. According to INSEE, this result is unusual given that in 2006 [16-20] growth was almost 2.5 percentage points above the average over the decade (3.9%) and 4.4 percentage points above the national rate of growth. With GDP per capita at €13,800, the increase in volume was 2.8%. In part, per capita income growth was limited by a population increase of about 3.8% per annum. The high rate of growth at this time stemmed mainly from the exceptional level of investment in the space industry. Furthermore, the infrastructure works of the Soyuz and Vega programme, the resumption of public procurement, and private investment have helped to amplify this dynamic. Investment increased by 27.7% in terms of volume and contributed 5.7 percentage points to GDP growth. Government expenditure has also been on an upward trend. The construction sector has benefited from the effects of investment, with value added rising to 27% of GDP. Private services, industry and gold mining also benefited from growth. In 2007 overall value added increased to 6.8% in volume, or by 3.5% compared to 2005. Industry and construction also accelerated sharply. Several patterns are apparent. French Guiana is experiencing growth that is mostly absorbed by population growth. On the other hand, the United Nations Development Programme Human Development (HDI) ranks French Guiana among the high human development countries such as Trinidad and Tobago, and Brazil. The business climate indicator is based on quarterly business surveys. It is centred around a long-term average of 100 and a standard deviation of 10. The higher the indicator, the better companies’ perception of the economy. In this regard, as Figure 2 shows, there has been a marked improvement in recent years, although the disruptive social movements interrupted this positive trend [21- 23].

Conclusion

French Guiana’s economic context corresponds to that of a transfer economy, not specifically of public transfers, even if there is an abundance of them. Private transfers are significant and provide the basis for an increasing role to be played by that sector. The other characteristic of the economy is the role played by the French state in defining the institutional framework, administering prices, and regulating monetary and financial availability. Many of these activities have acted to constrain the private sector.

References

- Magnan D (2002) On Fishing in Guyana: The Conditions for Sustainable Development paper presented at the CAASSIDD symposium, Cayenne.

- Mignot M (2001) Perspectives of employment in Guyane 2001-2006. CNES Mission of Guyane, Conseil of Control, IEDOM, Cayenne.

- Panhays B (2002) Dynamics of the space sector in the Guyanese economy. paper presented at the CAASSIDD colloquium, Cayenne.

- Radjou N (2002) Underdevelopment of French Guiana: The mirage of status. paper presented at the CAASSIDD colloquium, Cayenne.

- Radjou N (2005) Development and institutional framework. laboratory document, CAASSIDD/LEAD EA 2438 Guyana, Cayenne.

- Radjou N (2007) Development, financial autonomy and taxation in Overseas To understand guyana today Editions Ibis Rouge, Cayenne.

- Rosele Chim P, Raboteur J (1994) The Caribbean: Migrations and regional labour markets: functioning, DR, 3 DISEC network, LEAD, University of the French Antilles and Guyane, Cayenne.

- Raboteur J (2007) The new tourist map of Guyana to understand La nouvelle carte touristique de la Guyaneguyana today, Ibis Rouge Editions, Cayenne.

- Rosele Chim P, Raboteur J (2003) Income Sensitivities and Informal Practices: Paradoxes in Developing and Newly Industrialized Countries, Working Papers, CAASSIDD, Cayenne.

- Rosele Chim P (2007) Development imbalances through migration and informality in Guyana, to understand Guyana today Ibis Rouge Editions, Cayenne.

- Rosele Chim P (2007) The growth pole effects of the European space industry on the economy of French Guiana. Journal Life and Economics, Flight, pp. 1174-1175.

- Rosele Chim P (2007) Poverty and Inequality: Development Imbalances in Guyana To Understand Guyana Today, Ibis Rouge Editions, Cayenne.

- Rosele Chim P (2008) Geophagy and Geosophy in Development: A Comparative Approach North-East Amazon-East Caribbean. Canadian Journal of Regional Science.

- Rosele Chim P (2009) Informal Economy and Tourism in the French Amazon, Canadian Review on Territories and Tourism.

- Rosele Chim P (2010) International growth pole, innovation effect of the development of the European space industry in French Guiana. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 31(1-2).

- Rosele Chim P (2010) Local airfields and territorial development: Amazonia-French Caribbean space analysis. Working papers, BETA MINEA EA 7485, Cayenne: University of French Guiana.

- Rosele Chim P (2011) Development and imbalance in a Caribbean context on: French Guiana. In: Kiminou R (Ed.), Economy and business law of the Caribbean and Guyana, Publibook Edition Publibook, Paris, France.

- Rosele Chim P (2011) On the opening of the French Guiana economy: Development and imbalance. In: Kiminou R (Ed.), Economy and business law of the Caribbean and Guyana, Publibook Edition Publibook, Paris, France.

- Rosele Chim P (2012) Economic intelligence and industrial development of territories: Some aspects of sustainability. Working papers, BETA MINEA EA 7485, Cayenne: University of French Guiana.

- Rosele Chim P (2019) Migration growth and development in the South American trajectory: Haiti, French Guiana, Brazil, Chile, RIELF International Review of French-speaking Economists n°6, Poznan, Poland.

- Rosele Chim P, Panhuys B (2018) The digitization of the economy and the new dynamics of industrial firms. Annals of Social Sciences Management Studies 2(3).

- Rosele Chim P (2018) Numerical economy and new industrial firm power. Annals of Social Sciences Management Studies 1(5).

- Seraphin H, Gowreesunkar V, Rosele Chim P, Duplan YJJJ, Korstanje M (2018) Tourism planning and innovation: The Caribbean under the spotlight, Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 9(1): 384-388.