Response To Spiritual Pain and Practice of ACP Support in Elderly Patients with End-Stage Lung Cancer

Satoru Sagae1*, Nayu Someki2, Ayako Iizuka2, Ayumi Tanimoto3, Syuhei Ohkura4 and Riyo Shinya5

1Internal Medicine Palliative care, Sapporo Kojinkai Memorial Hospital, Japan

2Department of Nursing, Sapporo Kojinkai Memorial Hospital, Japan

3Department of Pharmacy, Sapporo Kojinkai Memorial Hospital, Japan

4Department of Rehabilitation, Sapporo Kojinkai Memorial Hospital, Japan

5Department of Medical Coordination, Sapporo Kojinkai Memorial Hospital, Japan

Submission:August 21, 2025;Published: September 03, 2025

*Corresponding author:Satoru Sagae, Medical Department, Internal Medicine Palliative Care, Sapporo Kojinkai Memorial Hospital Sapporo City, Japan

How to cite this article: Satoru S, Nayu S, Ayako I, Ayumi T, Syuhei O, et al. Response To Spiritual Pain and Practice of ACP Support in Elderly Patients with End-Stage Lung Cancer. Palliat Med Care Int J. 2025; 5(1): 555651.DOI: 10.19080/PMCIJ.2025.05.555651

Abstract

We present the case of an 89-year-old woman with terminal lung cancer who received palliative care without curative treatment. Following disclosure of her diagnosis, she experienced profound spiritual pain encompassing relational, autonomy-related, and temporal concerns. A multidisciplinary palliative care team (PCT) provided continuous psychosocial interventions and facilitated advance care planning (ACP). Repeated conversations clarified her values, leading to written consent for an advance directive and a do-not-attempt-resuscitation (DNAR) order. Her wish to visit her home and reunite with her pet was fulfilled, contributing to her sense of spiritual fulfilment. As dyspnoea and delirium progressed, deep sedation was introduced using morphine and benzodiazepine, and she passed away peacefully, surrounded by loved ones. This case underscores the importance of addressing spiritual pain and integrating ACP as an ongoing dialogue. Spiritual care and ACP were not singular interventions but continuous processes that allowed the patient to reach the end of life with dignity and peace. By highlighting the interplay between spiritual suffering, psychosocial support, and decision-making, this report contributes educational insights into the practice of holistic palliative care.

Keywords:spiritual pain; advance care planning; palliative care; terminal lung cancer; deep sedation

Abbreviations: PCT: Palliative Care Team; ACP: Advance Care Planning; DNAR: Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation; EAPC: European Association for Palliative Care; WHO: World Health Organization; CT: Computed Tomography; ADL: Activity of Daily Life

Introduction

Spiritual pain in advanced cancer has been described as one of the most profound forms of suffering, encompassing meaning, identity, and relationships [1]. Elderly patients are especially vulnerable, as they face existential issues such as acceptance of mortality and reconciliation with past choices [2,3]. International guidelines emphasize that spiritual care is central to palliative medicine. The European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) defines spiritual care as addressing suffering in multiple dimensions, while the World Health Organization (WHO) similarly promotes a holistic model that integrates physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains [4-6]. In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has issued guidelines on decision-making at the end of life, highlighting the importance of Advance Care Planning (ACP) and spiritual needs [7]. ACP has been shown to improve alignment between patient preferences and care received, reduce unwanted interventions, and support families during bereavement [8,9]. A multinational consensus further emphasizes that ACP should be understood as a process of ongoing dialogue, not a single event [10].

This report describes the care of an elderly woman with terminal lung cancer who experienced multifaceted spiritual pain. Her journey illustrates how a multidisciplinary team provided spiritual support and facilitated ACP, enabling her to approach death with dignity. By integrating clinical details with reflections on team practice, this case offers practical and educational insights for healthcare professionals engaged in palliative care.

Case Presentation

An 89-year-old woman with no significant comorbidities

developed a persistent cough in early 2024. At Hospital A, chest

CT demonstrated a right lower lobe tumor with pleural effusion

and obstructive pneumonia. Tumor markers were elevated, but

a biopsy was not performed because of her advanced age and

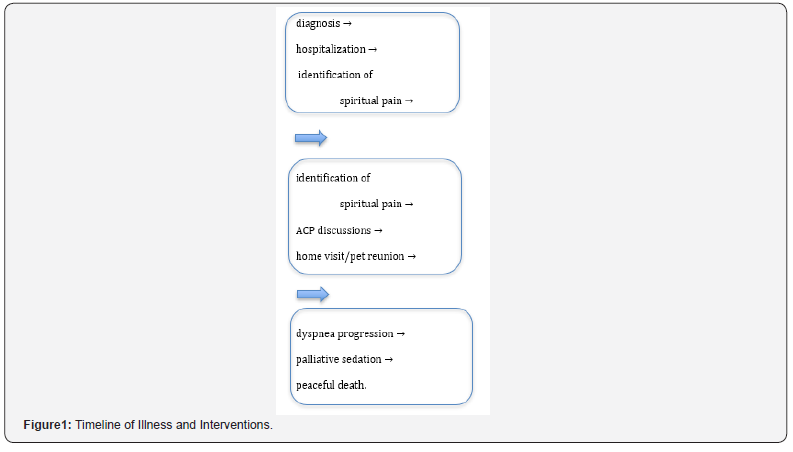

frailty. A clinical diagnosis of lung cancer was made (Figure1). She

was informed directly of her condition and told that her prognosis

was approximately three months. The disclosure occurred

without her family present. Later, she described this moment as

one of intense loneliness and despair, stating, “I felt abandoned in

that room.” Similar feelings of isolation after solitary disclosure

have been recognized as risk factors for existential distress [2].

In March 2024, she transferred to our hospital for palliative care.

On admission, she required 2 L/min of oxygen, had no pain,

maintained her appetite, and remained independent in ADLs.

Initially, she conversed cheerfully with the staff. However, within

days, she began expressing distress:

• “I do not want to be a burden to my family.”

• “I have no reason to live anymore.”

• “No one understands me.”

These statements reflected existential anguish rather than physical discomfort, corresponding to descriptions of spiritual pain in advanced cancer [1,11].

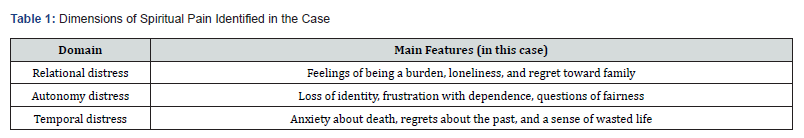

The PCT identified three domains of spiritual pain consistent

with previous literature [1,3]:

i. Relational distress – She feared burdening her son and

his wife, regretted past conflicts, and repeatedly said, “I should

have lived differently.” Despite daily family visits, she felt isolated.

ii. Autonomy distress – Loss of independence troubled her

deeply. She grieved her declining ability to walk alone, saying,

“Why me?” Her comments revealed doubts about divine fairness.

iii. Temporal distress – Death anxiety was frequent. She

described her past as “wasted” and feared approaching death

unprepared.

While in daily courses, her mood fluctuated dramatically. Some mornings she spoke of gratitude, while evenings brought tears of regret [12]. Nurses described her state as a “shaking heart,” reflecting the fragile oscillation between hope and despair [3] (Figure 1). Family members visited regularly. Conversations often revolved around practical matters such as meals and weather, but deeper dialogue was rare. The patient sometimes lamented, “I cannot say what I feel.” Recognizing this, staff facilitated structured family meetings where she could share her fears openly. Her son and his wife, initially overwhelmed, gradually became more able to listen. Throughout hospitalization, the PCT emphasized small acts of autonomy. She was encouraged to choose meal preferences, decide when to rest, and participate in discussions about medications. These gestures restored a sense of agency and dignity (Table1) .

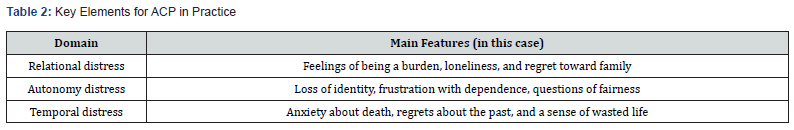

Interventions and ACP Process

Holistic care was supported by contributions from all disciplines. Physicians monitored disease progression and initiated ACP conversations. Nurses offered continuous bedside presence and empathic listening. Pharmacists explained opioid titration, counteracting stigma and fear of addiction [5]. Rehabilitation staff supported mobility, and the medical social worker coordinated family meetings and home visits. Weekly team meetings ensured a shared understanding of her condition and allowed adjustments in care plans. Multidisciplinary recognition of spiritual pain has been recommended in the literature as essential for effective support [11]. In late April, during temporary clinical stability, structured ACP conversations began. The physician asked, “What matters most to you in the time ahead?” She responded, “I want to be with my son and his wife, without causing trouble.” Nurses further explored her wishes, and she confirmed her preference to avoid invasive treatments such as intubation. An advance directive and DNAR order were documented in writing. She expressed relief, saying, “Now it is written clearly.” This aligns with evidence that ACP documentation provides psychological reassurance and improves care consistency [8,10]. Her family initially hesitated but accepted the decision after hearing the patient’s voice directly, echoing studies showing that family involvement strengthens ACP effectiveness [13]. One of her strongest wishes was to return home and see her pet dog. PCT coordinated logistics, including portable oxygen and family support. During Golden Week, she visited home twice [14]. On returning, she smiled, “Now I can rest in peace.” Such small but meaningful goals are consistent with dignityconserving interventions that have been shown to alleviate existential suffering [15] as the realization of hope. By mid-May, her symptoms progressed, and dyspnea worsened. Morphine was initiated and gradually titrated, consistent with guidelines for breathlessness in advanced cancer [7]. Despite pharmacological management, she developed anxiety and delirium. Nurses provided reassurance and environmental adjustments (private room, sunlight, music), yet distress persisted. Following family discussions, continuous palliative sedation was introduced with morphine and benzodiazepine [16]. The decision aligned with her documented preferences and family agreement, demonstrating the value of ACP in guiding end-of-life care [14]. She passed away peacefully in early June, surrounded by her family (Table 2).

Discussion

This case illustrates the significance of integrating spiritual

care and ACP in palliative care for elderly patients. Her suffering

manifested as multidimensional across relational, autonomy, and

temporal domains, consistent with prior conceptualizations [1,2].

Identifying these dimensions allowed interventions tailored to

each domain [17]. In continuous presence, her daily fluctuations

emphasized the importance of empathic presence. Spiritual care

is not about eliminating distress but about accompanying the

patient. This reflects Japanese studies highlighting the therapeutic

value of “being with” patients [3,11]. ACP as dialogue in this case

was a series of conversations rather than a single event, aligning

with international consensus [10,13]. Documentation not only

guided medical decisions but also validated her autonomy.

This demonstrates ACP’s dual function: practical planning and

existential support. Fulfilling her wish to see her pet provided

profound relief, consistent with dignity-conserving care models

[15]. Exploring and realizing such personal hopes should be a

routine part of palliative care. Educational implications were

included:

• Teamwork: A multidisciplinary approach was essential

[11].

• Communication: Open-ended questions and empathic

listening proved crucial [5].

• Family involvement: Facilitated meetings enabled

honest dialogue, consistent with prior findings [13].

Challenges still exist. Measuring outcomes of spiritual care remains difficult. Observable improvements such as calm expressions or enhanced family communication are subjective [5]. Developing validated tools is a priority for future research. In Japan, decision-making often involves families; however, this case respected individual autonomy while ensuring family inclusion, consistent with culturally adapted ACP guidelines [14] as a cultural reflection. As broader implications, the case highlights that addressing spiritual pain and implementing ACP enhances patient dignity, strengthens family relationships, and ensures care consistent with values [18]. Such practices are highly relevant for community physicians and nurse practitioners [19, 20], who can adopt similar approaches in their daily clinical care.

Conclusion

Spiritual pain in terminal illness is multidimensional, encompassing relational, autonomy-related, and temporal suffering. Effective response requires sustained listening, empathic presence, and recognition of fluctuating emotions. In this case, an elderly woman with terminal lung cancer was supported by a multidisciplinary team. Through repeated dialogue, ACP documentation, and fulfilment of personal wishes, her values were honored. Ultimately, palliative sedation was introduced in alignment with her preferences, enabling a peaceful death. This report demonstrates that ACP is more than documentation-it is a dynamic process of exploring values and reconstructing meaning. By accompanying patients through their “shaking hearts,” healthcare professionals can support dignified and meaningful end-of-life experiences.

References

- Murata H (2003) Spiritual pain and its care in patients with terminal cancer: construction of a conceptual framework by philosophical approach. Palliat Support Care 1(1): 15-21.

- Morita T, Kawa M, Honke Y, Kohara H, Maeyama E, et al. (2004) Existential concerns of terminally ill cancer patients receiving specialized palliative care in Japan. Support Care Cancer 12(2): 137-140.

- Tamura K, Kikui K, Watanabe M (2006) Caring for the spiritual pain of patients with advanced cancer: A phenomenological approach to the lived experience. Palliat Support Care 4(2): 189-196.

- Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, Reller N (2014) Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med 17(6): 642-656.

- Balboni TA, Fitchett G, Handzo G, Johnson KS, Koenig HG, et al. (2017) State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research. J Pain Symptom Manage 54(3): 428-440.

- World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into responses to humanitarian emergencies and crises. WHO, 2018.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan). Guidelines on the decision-making process in end-of-life care. 2018.

- Johnson S, Butow P, Kerridge I, Tattersall MH (2016) Advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology 25(4): 362-386.

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A (2014) The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 28(8): 1000-1025.

- Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, Hanson LC, Meier DE, et al. (2017) Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 53(5): 821-832e.

- Ichihara K, Ouchi S, Okayama S, Kinoshita F, Miyashita M, et al. (2019) Effectiveness of spiritual care using a spiritual pain assessment sheet for advanced cancer patients. Palliat Support Care 17(1): 46-53.

- Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Okamoto T (2010) Japanese Task Force for Spiritual Care. Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 39(6): 993-1002.

- Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA et al. () Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 18(9): e543-e551.

- Miyashita J, Morita T, Sato K, Mori M, Okawa K, et al. (2022) Culturally adapted consensus definition and action guideline: Japan’s advance care planning. J Pain Symptom Manage 64(6): 602-613.

- Chochinov HM (2022) Dignity-conserving care: a new model for palliative care 287(17): 2253-2260.

- Maeda I, Morita T, Yamaguchi T, Inoue S, Ikenaga M, et al. (2016) Effect of continuous deep sedation on survival in patients with advanced cancer (J-Proval): a propensity score-weighted analysis of a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 17: 115-122.

- Murata H, Morita T (2006) Japanese Task Force. Conceptualization of psycho-existential suffering by the Japanese Task Force: the first step of a nationwide project. Palliat Support Care 4(3): 279-285.

- Bernacki RE, Block SD (2014) for the American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force Communication About Serious Illness Care Goals: A Review and Synthesis of Best Practices. JAMA Intern Med 174(12): 1994-2003.

- Rosa WE, Izumi S, Sullivan DR, Lakin J, Rosenberg AR, et al. (2023) Advance Care Planning in Serious Illness: A Narrative Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 65(1): e63-e78.

- Takenouchi S, Uneno Y, Matsumoto S, Chikada A, Uozumi R, et al. (2024) Culturally Adapted RN-MD Collaborative SICP-Based ACP: Feasibility RCT in Advanced Cancer Patients J Pain Symptom Manage 68(6): 548-560.

- Murata H (2003) Spiritual pain and its care in patients with terminal cancer: construction of a conceptual framework by philosophical approach. Palliat Support Care 1(1): 15-21.

- Morita T, Kawa M, Honke Y, Kohara H, Maeyama E, et al. (2004) Existential concerns of terminally ill cancer patients receiving specialized palliative care in Japan. Support Care Cancer 12(2): 137-140.

- Tamura K, Kikui K, Watanabe M (2006) Caring for the spiritual pain of patients with advanced cancer: A phenomenological approach to the lived experience. Palliat Support Care 4(2): 189-196.

- Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, Reller N (2014) Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med 17(6): 642-656.

- Balboni TA, Fitchett G, Handzo G, Johnson KS, Koenig HG, et al. (2017) State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research. J Pain Symptom Manage 54(3): 428-440.

- World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into responses to humanitarian emergencies and crises. WHO, 2018.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan). Guidelines on the decision-making process in end-of-life care. 2018.

- Johnson S, Butow P, Kerridge I, Tattersall MH (2016) Advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology 25(4): 362-386.

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A (2014) The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 28(8): 1000-1025.

- Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, Hanson LC, Meier DE, et al. (2017) Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 53(5): 821-832e.

- Ichihara K, Ouchi S, Okayama S, Kinoshita F, Miyashita M, et al. (2019) Effectiveness of spiritual care using a spiritual pain assessment sheet for advanced cancer patients. Palliat Support Care 17(1): 46-53.

- Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Okamoto T (2010) Japanese Task Force for Spiritual Care. Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 39(6): 993-1002.

- Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA et al. () Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 18(9): e543-e551.

- Miyashita J, Morita T, Sato K, Mori M, Okawa K, et al. (2022) Culturally adapted consensus definition and action guideline: Japan’s advance care planning. J Pain Symptom Manage 64(6): 602-613.

- Chochinov HM (2022) Dignity-conserving care: a new model for palliative care 287(17): 2253-2260.

- Maeda I, Morita T, Yamaguchi T, Inoue S, Ikenaga M, et al. (2016) Effect of continuous deep sedation on survival in patients with advanced cancer (J-Proval): a propensity score-weighted analysis of a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 17: 115-122.

- Murata H, Morita T (2006) Japanese Task Force. Conceptualization of psycho-existential suffering by the Japanese Task Force: the first step of a nationwide project. Palliat Support Care 4(3): 279-285.

- Bernacki RE, Block SD (2014) for the American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force Communication About Serious Illness Care Goals: A Review and Synthesis of Best Practices. JAMA Intern Med 174(12): 1994-2003.

- Rosa WE, Izumi S, Sullivan DR, Lakin J, Rosenberg AR, et al. (2023) Advance Care Planning in Serious Illness: A Narrative Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 65(1): e63-e78.

- Takenouchi S, Uneno Y, Matsumoto S, Chikada A, Uozumi R, et al. (2024) Culturally Adapted RN-MD Collaborative SICP-Based ACP: Feasibility RCT in Advanced Cancer Patients J Pain Symptom Manage 68(6): 548-560.