The Special Model for End of Life Discussions in the Emergency Department: Touching Hearts, Calming Minds

Fatimah Lateef*

Dept of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Submission:October 05, 2020;Published: October 12, 2020

*Corresponding author: Sorush Niknamian, CEO and Executive Manager of Violet Cancer Institute, Federal Health Professionals and Department of Defense (DoD). VA, USA

How to cite this article: Fatimah L. The Special Model for End of Life Discussions in the Emergency Department: Touching Hearts, Calming Minds. Palliat Med Care Int J. 2020; 3(5): 555623. DOI:10.19080/PMCIJ.2020.03.555623

Abstract

Today, Emergency Physicians are beginning to initiate and manage more and more end of life (EOL) care patients in the emergency department (ED). Despite all the challenges that makes the ED non-condusive for these discussions, whether from the perspective of the concept of emergency care or the lay-out of EDs, there must be strategies and action plans to incorporate EOL care and discussions into the modus operandi of EDs. Emergency Medicine (EM) programmes and departments must be prepared to invest in dedicated time, training, space, resources and partnership networks to ensure EOL care and discussions can be carried out efficiently and effectively.

The author is proposing a framework, The SPECIAL Model, for EOL discussions and management in the ED. It is being proposed to handle a delicate, emotional and sensitive matter. With adequate training planned by EM programmes, experience and the use of the SPECIAL Model, EPs can certainly aspire to deliver safe and high quality EOL care in the ED, 24 hours a day. SPECIAL is a pneumonic : S (Structured ), P(Patient-centric Plans), E(Environment), C(Constant, Care Updates), I( Interpersonal Communications), A(Advanced Care Plans and other Advanced decisions), L(Life Quality). It is easy to remember and can be used as a memory jerk when EPs have to discuss these challenging issues.

Keywords:End of life care; Palliative care; Emergency department; Comfort care; Special model

Introduction

In general, End of Life (EOL) care combines the broad range of health and community services that can care for the person at the end of their life. Quality EOL care can be realized when strong networks exist between all levels of care providers (ie. Specialists, palliative care providers, primary care physicians, counsellors and community support staff and family members) who work together to meet the needs of these patients. EOL care in the Emergency Department (ED) refers to the care provided in situations whereby serious deterioration in health occurs, due to evolution of an existing disease or the acquisition of an acute or new condition which can be life-threatening. The imminent risks to the person can be multi-factorial, but certainly poses a threat to the life of a patient/ person [1,2].

The Emergency Department (ED) is a place whereby emergent and acute health and medical problems are managed. It represents an interphase between the community and the hospital. It is like a doorway to access medical care. Maximum efforts are put in to save lives and limbs. However, active resuscitation may not be the optimal management for every single one of these patients [2-5] For example:

a)Patients who are seriously ill with advanced stage/ terminal diseases

b)Patients on palliative care, whereby the decision has already been made for comfort measures and holistic care to be delivered and

c)Patients with extremely poor prognosis whereby any interventions will not make a difference to survival and recovery.

Some of these patients may have made their decision on having a ‘good death’, away from the hustle of the ED, with good pain control and no invasive interventions [3]. Thus, for this group of patients, who may present to the ED, a proper pathway and approach is necessary. The process of dying is multi-dimensional and may not be the easiest to handle, especially with the combination of the physical, psychological, spiritual and social elements that need to be addressed. Even as EOL care is usually managed by doctors and nurses in Palliative Care, Medical Oncology, Internal Medicine and Hospice Care, more and more patients are presenting to the ED at various staged of their end of life journey. There may be a variety of reasons for this, including: the ageing population across the world, better medical care and people living longer, better management of chronic diseases which means these patients also live longer and may suffer more complications especially during the last decade of their lives, industrialization and its associated increased fatal and serious accidents and injuries. One other reason could also be that the ED is open 24 hours and readily accessible in most countries [4,5-10].

Currently there is no available or highly recommended screening tool for ED identification of the dying patient. This is usually done based on individual emergency physician’s (EP) professional assessment, based on the clinical presentation and unique patient factors. EOL is today well recognized as a life stage. The following are some categories of trajectories of EOL: [11-16]

1) Terminally ill patients with a final stage or terminal decline. An example of the group of patients in this category are those with advanced stage cancer. For such patients, when they are in their pre-terminal stages, they may remain relatively stable with occasional minor decline in health status. However, when they enter the terminal stages, which may extend over months to years, the decline will be steeper [15,16].

2) Patients with sudden death. These are the patients who are well or relatively well and not expected to die. They may be patients who have little interaction with the healthcare system. A catastrophic, acute event may bring forth their EOL. Examples will be a previously well patient involved in a serious road traffic accident, a fit younger patient who sustain sudden cardiac death whilst running a marathon or an adult with no medical problems or chronic diseases who succumbs to sepsis by contracting an infectious disease.

3) Patients with long term chronic disease associated with organ failure and dysfunction. These patients may have a waxing and waning course and may have multiple admissions to the hospital for exacerbations and complications. Examples would be those with end stage renal failure (ESRF), chronic obstructive lung disease (COLD), terminal stage congestive heart failure and cardiomyopathy [4,6,7,17,18].

4) Patients in the group are often described as having the “frailty syndrome”. [5,18-20] This can happen as part of the ageing process and physiological events, with the culmination of these effects on the human body. This can commences in the last couple of decade of life, but for those with long term chronic diseases such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple cerebro-vascular events, causing them to be bed-bound and fully dependent, the degenerative changes can be brought forward. This group will usually show a pattern of slow and gradual decline. However, on occasions, in the event they develop any serious complications, their decline can be accelerated and their EOL trajectory may be shortened.

Bailey, Murphy and Porock termed Category 2 deaths as spectacular or unexpected deaths in the ED. These are usually linked to trauma and serious acute illnesses. Categories 1,3, and 4 patients death was termed subtacular, i.e expected death from advanced or terminal illnesses [2]. Whichever category the patient comes under, the focus must be on the care and needs of the patient. Decisions on escalation or non-escalation of care has to be decided. Patients who fall in categories 1,3 and 4 may already have had their EOL discussions carried out with their primary healthcare providers. Their families would usually also have been appraised [8,15,20-23]. However, from amongst them, there will be a proportion who have not had their EOL decisions and plans established. Thus when they present to the ED with an acute condition, the emergency physician may need to ascertain how critical their condition is and may be required to commence the EOL discussions with them or their family members. There may also be occasions when the topic has been brought up prior, but a decision has not been reached for a variety of reasons [9,10,11,22]. These discussions can be very important and strategic as they may affect subsequent placement and also the right siting of care for the patient [22,23]. For patients in category 2, death is acute, unplanned and sudden and the EOL discussions must be initiated and discussed, for the first time, during that ED presentation. EPs must remain astute to be able to recognize when treatment is futile and non-beneficial [17,19,20].

Challenges in Handling EOL Discussions in the ED

Many have argued that the ED is not the best place to discuss EOL issues. The busy and hectic environment is not the ideal place to conduct such discussions. Moreover EOL discussions are difficult conversations and will optimally need a calm and quiet environment. The rushed and busy environment, with active resuscitations and time constraints are certainly challenges. Not forgetting the heavy workload, whereby the time spent per patient may often not be the most optimal. As a result, short-cuts are often applied. This may cause inadequate understanding and appraisal of the circumstances surrounding the death. In EDs of developing and third world countries, the crowded situation would certainly make EOL discussions extremely challenging [1,2,8,12].

Many have also highlighted that the ED design often lacks a condusive space for these conversations. These are certainly topics not to be discussed at the bedside or in the corridors of the EDs. At the ED at Singapore General Hospital (SGH) for example, we have a dedicated “family room”, specially constructed for such discussions. Having a dedicated space as this is also a JCI (Joint Commission International) requirement for such conversations to be carried out in Eds [24,25]. Everyone would strive to have the best, safest and highest quality discussions on EOL issues. Thus the need to also have the family and relevant next of kin come in to the ED, often on an urgent basis. This may prove challenging. In fact some of these critically ill patients may come in with altered mental state and it would take some time for the staff, police and authorities to trace their family contacts. If there are foreigners in such circumstances, contacting their relatives can be even more challenging.

Another important consideration is the culture of the local population. In countries with multi-ethnic, multi-racial and multireligious population, each EOL discussion can be laced with so much sensitivities [9,10]. Culture can influence the choices that are made. Culture can have an influence on who stays with you or a loved one, as they are dying. Cultural beliefs and practices can certainly trump strategy. Dying is indeed a profound process of transformation for the patient as well as their family members. EPs can be faced with a diversity of cultural practices from their patients’ perspectives. The communications process may also need to be customized accordingly e.g. some culture are more vocal and direct, whereas others place a relative emphasis on nonverbal communications, nonverbal gestures and quiet reflection [10,26,28,29]. At times, there may be conflicts or differences in understanding between the ED staff and family members. One example could be pertaining to the feeding of some of these patients on EOL care pathways. Feeding patients, even at this stage of their life’s journey is important in the Chinse culture, where the practice of “mortals treat eating with heavenly importance” is given high regards. It is believed that the patients must not suffer from hunger as it may constitute a commission of sim by the family. The family will request to feed their loved ones, even as it can be considered inappropriate due to the risk of aspiration. This example can cause discomfort and stress to the ED staff [2,30,31].

At times, if the family does not speak the same language, interpreters will be required and it becomes critical to be able to get the message across, pace the messaging appropriately and be observant of the responses. It is important to also confirm their understanding in such cases. As EPs are usually not the primary doctors of these patients, they may not have built a relationship, nor rapport with the patients and their family members. This, however, does not mean they cannot conduct the EOL discussion effectively and efficiently. Thus, the awareness of some of these factors, provision of training as well as being conscious in the way we practice will certainly help the EPs carry out what is required efficiently, effectively, honestly, empathetically and as ‘human’ as it can get [31-33].

Requirements for EOL Care Discussions

As it is extremely challenging to handle EOL care issues at the ED, there are certain interventions that institutions can have to facilitate the unenviable task EPs have to carry out. Some of these include:

Dedicated training

EOL communications training and sharing can be introduced during Medical Officer and Residents training and teaching sessions in the ED. It is also to be incorporated into the Emergency Medicine training curriculum. The EP faculty helps provide supervision and mentorship. The session incorporates interactive lectures, practical training using standardized patients or volunteers and demonstrations conducted by faculty, who take the ‘hot seat’ to show how to handle the challenges in the communications process. The scenarios can be written based on real cases that happen in the ED, in the context of the work EPs do. On occasions, colleagues from Medical Oncology and palliative care are invited to sit in and share as well. During medical students posting, their communications sessions would also include a scenario based on EOL care communications in the ED. In fact simulation-based learning is very useful for this. Computer based simulation , virtual simulations and even use of avatars ( who represent the patients or relatives) can provide useful training and practice [34,35].

Dedicated space

EOL conversations are not suitable to be discussed standing at the bedside. They much be done in a place/ room with suitable ambience, couches to sit, in a calm and quiet environment. Privacy must be provided and confidentiality must be maintained. This is also one of the criteria and requirements by the Joint Commission and Joint Commission International. Whether it is a single family member or many members of a multi-generation, expanded family, this is necessary [24]. Staff or doctors discussing this should bring along 1 or 2 colleagues. They could be doctors or nurses. In some institutions dedicated councilors or social workers are on this team as well. These colleagues play several role: as an ally to help explain collaboratively with the spokesperson, as a witness to the said conversation on EOL care which will subsequently have to be recorded into the patient’s notes or case records and also to assist in case any family members break down and need assistance such as a shoulder to cry on, tissues to cry into or a cup of drink.

Dedicated time

Dedicated time for training is important as discussed in point 1 above. However, dedicated time during a shift to be able to execute the EOL conversation adequately, is also necessary. Whilst it is impossible to allocate specific amounts of time for this as it is variable with different patients and different families, the doctors doing these discussions must not appear rushed or bring up time constraints. The doctor should update his/ her colleagues to cover him/ her whilst he holds the conversation. From personal experience in the ED for some 30 years, this time taken is not excessive and is usually manageable.

Dedicated resources

Teaching and training resources are needed. Articles, videos and demonstrations are useful. The room or specific area mentioned above is also a necessary resource. Some EPs may be interested to attend further training and courses on this topic and they should be supported and funded. Cross cultural resources and sharing sessions are also very useful, especially in places such as Singapore which has a multiracial and multi-religious society.

Dedicated collaborative support and partnerships

EPs can lead and manage collaborative efforts with other physicians and members of the healthcare tam to endorse philosophies that support quality EOL care in the ED, gather necessary resources and develop policies as relevant. . These networks are crucial. Support can come from staff from Palliative Care, Medical Oncology, Social Services, Chaplain Services etc. These relationships have to be built early, even from the stage when training is done together. Moreover, as the handling of EOL issues can be very demanding and emotional, support resources to help the ED staff navigate any ethical dilemmas or distressing circumstances will be very useful. Also, for protocols and pathways, it is helpful to run these by the hospital legal advisers for clearance and advice. In Singapore, partnerships with nongovernmental organizations such as Health Promotion Board and Agency for Integrated Care are very help in organizing seminars and dialogue sessions to help the public understand more about EOL care issues and ACPs. In some of these sessions, religious leaders are invited to sit in and provide inputs from the religious and spiritual perspectives.

The Special Model

As more and more EOL care and discussions are carried out in the ED, we are proposing the SPECIAL Model for discussion of EOL care in the ED. As every EOL situation is unique, the suggested model should be customized and used appropriately. The pneumonic, SPECIAL has been carefully selected. SPECIAL, according to the Cambridge Dictionary can mean, help in a particular esteem, great or important, or with a particular purpose [36]. This Model represents all of these. It is being proposed to discuss a delicate, emotional and sensitive matter. With adequate training planned by EM programmes, experience and the use of the SPECIAL Model, EPs can certainly aspire to deliver safe and high quality EOL care in the ED, 24 hours a day. SPECIAL is a pneumonic : S(Structured), P(Patient-centric Plans), E(Environment), C(Constant, Care Updates), I(Interpersonal Communications), A(Advanced Care Plans and other Advanced decisions), L(Life Quality). The details for the pneumonic is discussed below:

Structured

The beginning of any such conversations should come with a structured plan. Logical, stepwise explanation will help to ensure continuity. It should be structured so that laypersons will find it easy to follow the thought processes and links between relevant parts. As bringing up EOL discussions for the first time in the ED is challenging, exploring the background and circumstances of the patient and family will be helpful. Establishing the relationships between the characters in play early is also beneficial. It is important to check on the past medical history, disease background and how much the patient and family members already know. This can be a good starting point, so that one will know how far and how deep to direct the discussion and information sharing. If any existing disease has been staged before (e.g cancer stage, or mild versus advanced), or treatment and interventions have been decided ( e.g active, palliative, conservative), it can help set the initial stage for the ED physician. ‘Structured’ also means to set the steps in logical order and be as systematic as one can so that the lay person can follow the explanation appropriately, make sense of it and ask the right questions for clarifications.

Patient-Centric Plans

With the Structured background and information in mind, the next steps would be the patient-centric discussions. This is where the explanation on the current acute or ‘acute-on-chronic’ presentation and the status of the patient is brought forth. Using terms such as ‘critical’, ‘dangerously ill’, and ‘serious’, which can be understood by laypersons is useful, but it will deepen the understanding if explanations include descriptions such as ‘not responding to treatment such as fluid and antibiotics’ or ‘ the contractility function of the heart is very low at 15%’ (eg. correlating to the Ejection Fraction in an end stage cardiomyopathy patient).

It may be useful to itemize the list of issues faced by the patient and explain the interventions that is being done for each of these. An example would be:

a) Hypoglycaemia: it is being corrected by infusion of Dextrose and close monitoring of the blood sugar levels

b) Sepsis: blood cultures have been taken and the appropriate antibiotics have been commenced (early goal directed therapy)

c) Hypotension, dehydration: fluid resuscitation is being carried out with close monitoring of the vital signs for response

d) Infected sacral sore: de-sloughing and cleaning as well as dressing the wound will be carried out. X-Rays will be done to assess if the infection has affected the underlying bone.

e) Respiratory failure: this needs to be explained clearly as laypersons may have a different perception of the term. Use of supplemental oxygen by different adjuncts, use of BiPAP or cPAP versus intubation needs to be explained as well as the potential consequences and results that may be expected. Sharing the pros and cons of each may be raised, as the family members try to make a choice

f) This list will vary for different patients and can be customized accordingly. As one goes through the list of issues, it is a good opportunity to educate and correct misperceptions of the patients or family members at the same time. This can be entwined in the conversation or it could be a specific response to questions raised by the patient or family members.

Environment

The location where this EOL conversation takes place is also important. The best would be to have it done in a ‘family room’ or any room which is suitably equipped with seats/ couch. The ‘family room’ at the ED in Singapore General Hospital is a small room with couches which are facing each other. It is located outside the resuscitation room. The room is pastel colored and equipped with tissues. The furniture in such a room should be kept to a minimum and the ambience kept calm and quiet, away from the hustle and bustle of the ED. This room should have a door that can be shut and not have windows through which public members can peep in. Maintaining confidentiality is important. Conversations in the room are critical and the environment must support the ability of the relatives to assimilate and understand the information being shared. It must not be rushed and the EP must take control of this. It is really an art to be able to execute these crucial conversations, given the limited time EPs have and at the same time not to appear rude, uncaring and ruffled. The size of the room should not be too large, to appear cold and impersonal, but it must be big enough to accumulate family members and some families can have quite a number of members, including multi-generation ones. Even as these conversations are best kept to the main next of kin and closest relatives, there may be a necessity to let several other members sit in as well to be as inclusive as it possibly allows. This is also very true in the Asian context, where the extended family are very often involved in the collective decision making process as agreement and consensus is sought. These extended families can cut across three or more generations.

The other aspect of ‘environment’ is the location, where these patients are managed in the ED. Preferably they should be in a corner cubicle or a single room, for privacy. This way the family members can take turns to spend time with their loved ones. This act of letting the family be involved actively, will allow them to see that the patient is kept comfortable, not in pain and respected and cared for by the staff. It is necessary for the visitations to be supervised by the staff so that they can answer any questions the relatives may have. Supporting the family in their expression of love and concern for their loved ones and ensuring dignity is maintained in the final farewell will help provide the family members with peace of mind and closure.

(Constant) Care Update

Following the initial conversations, relatives appreciate regular updates, at intervals. In most EDs they may not be able to stay in the resuscitation room at the patient’s bedside for prolonged periods, and that makes this important. During these regular update sessions, better and deeper rapport can be built with the family members. In between the updates, relatives may come up with new queries which can also be addressed appropriately.

During these updates, they will appreciate to know how their loved ones were responding to the treatment initiated. Having the ability to update at intervals also allows pacing. This is where bite size portions of information are given each time. The information continues to be built up with each conversation. The updates may also cover management aspects such as the pain control, dyspnea control, management of the secretions and cough, vomiting or restlessness and agitation.

Interpersonal Communications

Communications represents the keystone of the whole process of EOL discussions. Why one person does better over another, may actually lie in their ability to execute the communications part well. This usually would have two components: the verbal and the non-verbal communications. The verbal communications is made up of the information, facts and details about the patient. These will be the same content covered under “structured” and “patientcentric plans”. Choose simple, non- medical jargon to explain what is necessary. The choice of words can make a difference between sounding offensive and caring. Often, details need to be repeated to reinforce the message to the families. It is good to be short and succinct with the messaging and not beat around the bush, but it is also important to ensure whilst doing this, EPs do not appear impersonal and cold.

The non- verbal communications skills or the body language is even more important. The eye contact, facial expression, tone of voice and a caring touch can all make a lot of difference. Congruency between the verbal and non-verbal communications is also important. Studies have shown the non-verbal components of these conversations can be even more crucial than the verbal communications [37-39]. This is also why training and simulation using standardized patients is now used widely to help doctors handle these situations better. Through debriefing session and video playback, we can become more conscious about how we sound and appear to others [35].

With the ever increasing numbers of EOL discussions going on in the ED today, it has become necessary to have training in communication skills in order to be able to carry out rapid, yet effective discussions with acutely distressed relatives and families, with whom rapport has never been established before. Appropriate communications and timely actions on the part of the ED team can have a positive impact on grieving family members. In fact, beyond that, it is not uncommon to hear EPs and nurses share their experiences interacting with such patients and their families and the impact it has left on them pertaining to reflection on the meaning of life, what death is about and some even linked this to the satisfaction in their job [1].

Advanced Care Plans (ACPs)

Making ACPs involve planning for future health decisions in the event a person may not be able to express their own wishes then. It is also important these ACPs are discussed with family members, care-givers and next-of-kin. In Singapore, an Advanced Medical Directive (AMD) may have been made officially and this is a legal document which clarifies a person’s future preference about their future treatment and medical care. When a patient presents to the ED in one of the 4 categories of presentation and the EP anticipates the need to bring on the EOL discussions, it is helpful to check if the patient has signed an AMD or has an ACP. There can be a generic or a specific type of ACP, especially pertaining to the care for patients in category 3, with known chronic long term diseases [40,41]. Besides ACPs, there are also other care orders EPs need to be familiar with and some of these are discussed below.

‘Do not resuscitate’ orders allow patients and their doctors to decide on the inappropriateness of CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) or ethically unjustifiable treatment due to these being deemed futile based on the context of the patient’s clinical condition [8,11] ‘Comfort care’ is defined as a patient care plan that is focused on symptom control, pain relief, and quality of life. It is typically administered to patients who have already been hospitalized several times, with further medical treatment unlikely to change matters. Comfort care takes the form of hospice care and palliative care [8,11,20]. ‘Palliative care’ on the other hand, is a medical specialty. Palliative care is thus care provided by specialists for people living with and dying from an eventually fatal condition and for whom the primary goal of care is quality of life. It focuses on relief of pain, symptoms and stresses of serious illnesses. The main goal is to reduce suffering and enhance (however possible) the quality of life these patients go through. Palliative care is appropriate at any point during a serious illness that a patient has to go through and can be provided at the same time as curative care. Palliative care is thus not synonymous with hospice care [12,20,23].

In the hospitals in Singapore, there is another term used i.e. “maximum ward management”. This is applied to patients in Categories 1, 3, and 4 whose management involves interventions which provide comfort and are conservative, with no invasive interventions. These patients are managed in the general ward rooms and their care will not be escalated to High Dependency or Intensive Care Units. These are also patients whereby there will be no CPR, no intubation and ventilation, in the event of cardiac arrest. It is part of our good practice on decision to withhold certain invasive treatment, which has been deemed futile in these appropriately selected patients.

In some countries and in some cases, EOL care should only involve use of pain control, analgesia, scopolamine, anxiolytics or hypnotics. In some others, patients can still receive venous access and hydration, antibiotics and appropriate broncho-pulmonary aspiration or suction of secretions. Optimizing the life quality can be challenging, yet important. At the end, its our goal to align with some of the good death principles [42].

Life Quality

This refers to the EOL quality. It thus makes a difference as to whether the patient is actively dying or not actively dying at the presentation to the ED. This decision has to be made based on the background of prior diagnoses and care plans, if these have been decided upon, because the patient has had previous multiple contacts with the hospital and follow up is taken from there. Otherwise, the EP would have to decide, using available prognostic criteria, as relevant to the patient’s presentation and status. Some of the existing criteria may include age, body temperature, mean arterial pressure, heart rate, level of oxygenation, pH, biochemical tests results, signs of multi-organ failure and even clinical signs of impending death, in the ED. Other factors such as status of ADL (activities of daily living), presence of co-morbidities and complications or factors such as patient’s wishes or existing care plans or DNR, if these have been decided [16].

Appropriate care and place of care is a professional medical judgement. The ED staff will decide and make reasonable arrangements customized for each patient, e.g. for comfort or palliative care, transfer to hospice or step-down community facilities, or to pronounce the death in the ED. The decisions made by the EPs will affect right siting of subsequent care for these patients and so it can be a very critical point. It is never possible to have a one size fit all model of care for all EOL care patients in the ED. The ED team communications and coordination framework must focus on providing appropriate quality end of life care. At times EPs may have to provide options and suggestions for the EOL care to relatives. Sometimes the relatives are unable to make the informed choice needed for the EOL care decision. This is especially so because it is always an emotive situation. EPs will find that they may have to help educate and guide relatives along the way, so they can understand EOL expectations of terminal illnesses and the dying process.

Conclusion

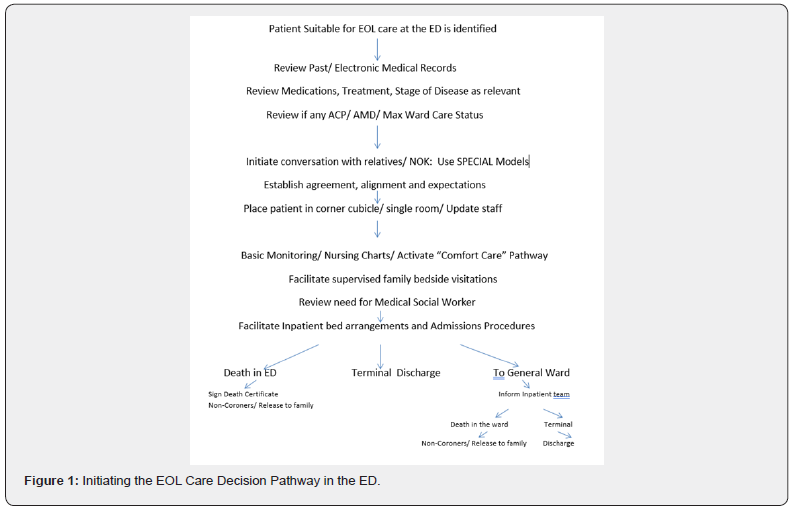

There are many challenges in handling EOL care issues in the ED. However, it is something that has arrived at our doorsteps and will continue to stay with us as EPs. Therefore, EPs must ensure we include initiating, discussion and management of EOL care in the ED as part of our armamentarium and training (Figure 1). We must continue to boost our capabilities and capacity to do this, just like we manage all other emergencies, crossing disciplines. The SPECIAL Model is one more to add to our “little black book”, as it will come in handy, anytime, death and dying issues crop up on us.

References

- Alqahtani AJ, Mitchell G (2019) End of life care challenges from staff viewpoints in EDs: Systematic Review. Healthcare 7(3):83.

- Bailey CJ, Murphy R, Porock D (2011) Dying cases in emergency places. Care for the dying in emergency departments. Soc Sci med 73(9):1371-1377.

- gmc-uk.org/End_of_life.pdf_32486688.pdf

- Arendts G, Carpenter CR, Hullick C,Burkett E, Nagaraj G, et al. (2016) Approach to death in the older emergency department patient. Emergency Medicine Australasia 28(6):730-734.

- Palace ZJ, Flood-Sukhdeo J (2014) The frailty syndrome. Today’s Geriatric Medicine 7(1): 18.

- Hogg KJ, Jenkins SMM (2012) Prognostification and identification of palliative needs in advanced heart failure: Where should the focus lie? Heart 98(7): 523-524.

- Pinnock H, Kendall M, Murray SA,Allison W,Levack P, et al. (2011) Living and dying with severe COPD; multiperspective, longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 342: d142.

- George NK, Kryworuchko J, Hunold RM,Ouchi K,erman A, et al. (2016) Shared decision making to support theprovision of palliative and end of life care in the emergency department: A consensus statement and research agenda.AcadEmerg Med 23(12):1394-1402.

- Lunn JS (2003) Spiritual care in a multi-religious context. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 17(3-4): 167-169.

- Bullock K (2011) The influence of culture on EOL Decision Making. Journal of Social Work in End of Life andpalliative Care 7: 83-98

- Downer J, Goldman R, Pinto R,EnglesakisM, Adhikari NKJ,et al. (2017) The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 189(13): E484-E493.

- Mierendorf S, Gidvani V (2014) Palliative care in the emergency department. The Permanente Journal 18(2): 77-85.

- Gerstorf D, Ram N, Estabrook R, Schupp J, WagnerGG, et al. (2008) Life satisfaction shows terminal decline in old age: Longitudinal evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study. DevPsychol 44(4):1148-1159.

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ,Lipson S, Guralnik GM, et al. (2003) Pattern of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 289(18):2387-2392.

- Tang ST, Liu LN, Lin KC,Jui-Hung C, Chia-Hsun H, et al. (2014) Trajectories of the multidimensional dying experience for terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 48(5):863-874.

- Yash Pal R, Kuan WS, Koh YW, Venugopal K, Ibrahim I, et al. (2017) Death among elderly patients in the ED: a needs assessment for EOL care. Singapore Medical J 58(3): 129-133.

- Chan GK (2004) End of life models and emergency department care. Acad Emerg Med 11(1):79-86.

- Chan GK (2011) Trajectories of approaching death in the emergency department: clinician narratives of patient transitions to the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manag 42(6):864-881.

- Meier DE, Beresford L (2007) Fast response is key to partnering with the ED. J Palliat Med 10(3):641-645.

- Jox RJ, Schaider A, Marckmann G, BorasioD (2015) European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for resuscitation. Resuscitation 95:302-311.

- Lamba S, Mosenthal AC (2012) Hospice and palliative medicine: a novel subspeciality of emergency medicine. J Emerg Med 43(5): 849-853.

- https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/-/media/jci/jci-documents/offerings/advisory-services/industry-services-program/ebpdc15sample.pdf?db=web&hash=5A79570EBAAEDFE3A2E8D408DEF5672D

- http://www.gmcuk.org/static/documents/content/treatment_and_care_towards_the_end_of_life_-_english_1015.pdf

- Wang DH (2016) Beyond code status: palliative care begins in the ED. Annals of Emerg Med 69(4): 437-443.

- Tse JWK, Hung MSY, Pang SMC (2016) Nurses perception of providing EOL care in a Hong Kong ED: a qualitative study. J Emerg Nurs 42(3): 224-232.

- Haraldsdottir E (2011) The constraints of the ordinary, “being with” in the context of EOL Nursing Care. Int J Palliat Nurs 17(5): 245-250.

- Wong M, Chan SW (2007) The experience of Chinese family members of terminally ill patients: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 16(12): 2357-2364.

- Lo RSK (2006) Dying: The last breath in: Chan CLW, Chow AYM, Eds. Death, Dying and bereavement: A Hong Kong Chinese Experience. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, pp.151-167.

- Haishan H, Hong Juan L, Tieying Z, Xuemei P (2015) Preference of Chinese general public and healthcare providers for a good death. Nurse Ethics 22(2): 217-227.

- Tyrer F, Williams M, Feathers L, Faull C, BakerI, et al. (2009) Factors that influence decisions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation: The views of doctors and medical students. Postgrad MedJ85(1009): 564-568.

- Forero R, McDonnell G, Gallego B (2012) Literature review on care at the end of life in the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine International.

- Fatimah Lateef (2020) Maximizing Learning and Creativity: Understanding psychological safety in simulation-based learning. J Emerg Trauma Shock 13(1): 5-14.

- Lateef F (2020) The standardized patients in Asia: Are there unique considerations? American J of Emergency andCritical care 3(1): 31-35.

- cambridge.org/dictionary/English/special

- Quest T, Asplin B, Carns C, Hwang Ula, PinesJM, et al. (2011) Research priorities for palliative and EOL care in the emergency setting. Acad Emerg Med 18(6): e70-e76.

- Zavotsky KE, Chan GK (2016) Exploring the relationships among distress, coping and the practice environment in ED nurses. Adv Emerg Nurs J 38(2): 133-146.

- Gloss K (2017) EOL care in emergency departments: A review of the literature. Emerg Nurse 25(2): 29-38.

- https://www.moh.gov.sg/policies-and-legislation/advanced-medical-directive

- https://www.singhealth.com.sg/rhs/live-well/Advance-Care-Planning

- Meier EA, Galligos JV, Mandross-Thomas LP,DeppCA,Irwin SA, et al. (2016) Defining a good death (successful dying): literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 24(4): 261-271.

- Kinghorn P, Coast J (2018) Assessing the capability toexperience a good death. A qualitative study to directly elicit expert views on a new supportive care measure in Sens capability approach. PLOS One 13(20): e0193181.

- Leung KK, Chen CY, Cheng SY, Tai-Yuan C, Ching-Yu C, et al. (2009) What do laypersons consider a good death. Supportive Care in Cancer 17(6):691-699.