Abstract

The Conservative Dual Criteria (CDC) method has improved decision-making accuracy in users when interpreting single case AB design graphed data. The AB design is the one most frequently used by educators. However, the effectiveness of this method with in-service special education teachers has not been investigated. The present study examined the effects of a virtual training package to improve the visual inspection skills of five special education teachers for data-based decision-making. The virtual training consisted of an instructional video on how to use the CDC method, access to a decision-making guide, and a brief training assessment via the online Canvas learning management system. A multiple baseline design across participants was used to evaluate the efficacy of the virtual training on decision-making accuracy of graphed data. All participants made marked improvements in decision-making accuracy after receiving the training. Participants also perceived the virtual training and the CDC method as socially acceptable activities. Implications for training and future research on the CDC method with special education teachers are discussed.

Keywords:Alzheimer’s Disease; Neurofibrillary Tangles; Chronic Neuroinflammation; Porphyromonas gingivalis

Introduction

A critical skill for special education teachers is accurately interpreting student performance data and, based on that analysis, adapting their instruction to improve student learning outcomes [1]. Students with intensive learning needs positively improve their academic performance across content areas when taught by educators with the skill and knowledge to revise instruction based on student learning data [2,3] established one of the first programs to develop this skill called Data-Based Program Modification. A key component was using student performance data as a proxy for intervention effectiveness. If a well-implemented intervention did not improve student performance, the program taught educators to adjust their teaching plan. The process of analyzing data and revising instruction continued until the student achieved a desired performance outcome or met grade-level expectations. Since that time this program, now known as data-based decision-making [4] has been adapted to include modern teaching innovations and current student learning needs [5-7].

DBDM is an important component of Curriculum-Based Measurements [8] typically used by special education teachers to address students’ remedial or intensive learning needs [9]. In CBM, student progress data is monitored and frequently graphed to determine whether the instructional strategy is effective or not [8]. Students’ performance is charted on a line graph including (1) the student’s baseline performance, (2) aimline representing the rate at which the student is expected to improve based on a performance goal, and (3) the student’s performance during or after the intervention was implemented [10]. The graphed data are interpreted by comparing the student’s rate of progress with the aimline. If the student’s performance does not improve at an appropriate rate, the teacher is encouraged to re-evaluate the instructional strategy and revise the plan. Educators are tasked with interpreting these graphs accurately to make good instructional decisions for students./p>

However, previous research has reported less than favorable outcomes when studying teachers’ ability to accurately interpret graphed data using AB type single case design or correctly link data to instruction [11,12] Yet, AB-graphs are the accepted standard method teachers use to interpret student progress data [13-15]. Thus, training educators to accurately interpret graphed data may be a meaningful way to prevent errors in DBDM and improve educational outcomes for students [4,16].

Training Professionals to Accurately Interpret Graphed Data

Strategies for training professionals with skills to accurately interpret graphs is continually developing [14,15] [17-19] determined if a 45-minute interactive virtual training module and decision-making guide would help special educators and behavior analysts improve two professional skills—reading AB graphs accurately and making appropriate instructional decisions.

Results indicated that participants demonstrated meaningful improvements in their data recognition and instructional decision-making skills while finding the training to be socially acceptable used a structured approach to learning visual analysis (VA) skills that included 2,400 AB-style graphs with visual aids, multiple styles of prompting, and reinforcement contingencies created from datasets generated from a first-order autoregressive model [20]. Half of the graphs (1,200) included visual aids (i.e., baseline mean and trend lines superimposed on the treatment phase) to help recognize treatment or null effects. These lines were calculated using the Conservative Dual Criteria method. Participants were shown graphs without the CDC lines and were prompted to decide whether the graph displayed the presence or absence of a treatment effect. All participants’ decision-making accuracy was enhanced by the use of CDC lines.

The Conservative Dual Criteria Method

Although other multi-component models have demonstrated positive results training individuals to interpret graphed data accurately, a simpler approach using structured visual criteria has also proven effective. The CDC method created by uses a statistical model (i.e., a revised version of the split-middle method) to create a trend line and a mean line from baseline performance. The calculated mean and trend lines are then superimposed on the treatment phase of the graph. In order to use this method, (1) a predetermined number of treatment data points must exceed or fall below the trend line using the binomial distribution test, and (2) a predetermined number of treatment data points must exceed or fall below the mean line depending on the intended effect of the treatment—either to increase or decrease a behavior based on one of two models—the Dual-Criteria (DC) or CDC. The CDC method differs from the DC by adjusting the mean and trend line 0.25 SD. This modification generates a “statistically conservative” mean and trend line, thus minimizing the risk of Type I error.

Although the DC method improved decision-making accuracy skills, the CDC method required empirical investigation. Consequently, evaluated the CDC method with six university students. During baseline, participants interpreted eight ABgraphs without CDC lines to determine whether or not data represented a behavior change. Results indicated that participants produced near-perfect accuracy when interpreting graphed data using the CDC method [22] created a four-step decision-making model to evaluate graphed data using the CDC method: (1) count the number of data points during the treatment phase, (2) use a reference table to find the number of points that fell in the expected direction of the treatment effect in order to conclude that a systematic change took place, (3) find the total number of points that were above or below the mean and trend lines, and (4) draw a conclusion using the decision rules and the number of data points. For example, assume a target behavior is expected to increase (acquisition), and the treatment phase consists of five observations of the target behavior. Using the model of Swoboda and colleagues, all five data points from the treatment phase must be greater than the mean and trend lines (i.e., no overlap) as calculated using the CDC method in order to determine a meaningful treatment effect. If, however, only four of the five data points are above the mean and trend lines, this would indicate a null treatment effect.

The structured visual criteria of the CDC method seem considerably less complex than other approaches for improving accurate decision-making skills when interpreting graphed data. Despite favorable results, the CDC method remains underutilized [23] even though other researchers have highlighted its practical utility (e.g., Moreover, Desimone and Garet; [24] found that professional development designed to foster teacher use of straightforward and specific tasks was more beneficial than attempts to only improve their content knowledge. found that a traditional lecture format designed to improve content knowledge did not produce a successful outcome. Rather, they found the CDC method improved accuracy immediately. Using virtual technology to assist teaching of VA skills has also generated positive improvements in decision-making. Finally, there is currently no research investigating whether in-service special education teachers would benefit from training in the CDC method to improve the accuracy of their decision-making skills from graphed AB data. With current trends and policies recommending improved teacher outcomes in DBDM investigating the potential of the CDC method with special education teachers is a topic worthy of empirical investigation.

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether special education teachers’ capability to accurately interpret graphed data is enhanced through virtual training in the CDC method. Our focus was on accurate interpretations of graphed data, which is an important component of DBDM. We did not study all component parts of DBDM, nor included other factors that may influence the decision-making process of educators (e.g., intervention fidelity). Rather, we wanted to take an intensive micro-approach in order to expand the literature base regarding special education teachers’ ability to accurately interpret graphed data to make instructional decisions. Part of our goal was to replicate and extend the work of previous researchers. Our goal was simply to focus on one important component of DBDM (i.e., accurate interpretation of graphed data) as a platform for others to expand this line of research to address the larger issues of DBDM. Consequently, this study is a first step in that direction.

Nonetheless, our study expands prior research in four ways. First, in-service special education teachers are the participants of interest in this study and virtual training using the CDC method has not been empirically studied in this population. Second, this study uses computer technology as the platform to deliver the training of the CDC method to participants. Third, training is conducted entirely by using a virtual learning management system (i.e., Canvas) and does not require extensive time for inperson interactions, meetings, or activities. The fourth way offers a systematic approach to solve a technical issue when using a multiple baseline design with the CDC method had no guideline for calculating effectiveness when intervention data exceeded 23 points. We offer a potential solution by developing a systematic method to calculate effectiveness when the total number of observations are outside the scope of current guidelines. These modifications broaden the potential utility of the CDC method. Social validity of training was also measured among participants in order to strengthen the social importance of a study’s conclusions [25].

Method

This study used a concurrent multiple baseline design across participants to evaluate whether virtual training in the CDC method improved the decision-making accuracy of special education teachers when examining graphed data. There are three benefits to this experimental design that are pertinent to the study’s purpose. First, this design is practical in applied settings and does not require the use of taxing experimental procedures, such as reversal or withdrawal phases, to demonstrate the effects of the treatment. Second, this design allows for the structured learning of unique skills within an experimental framework while also illustrating its potential in applied work settings or environments. Third, it mitigates specific threats to internal validity, such as history and maturation.

Participants and Setting

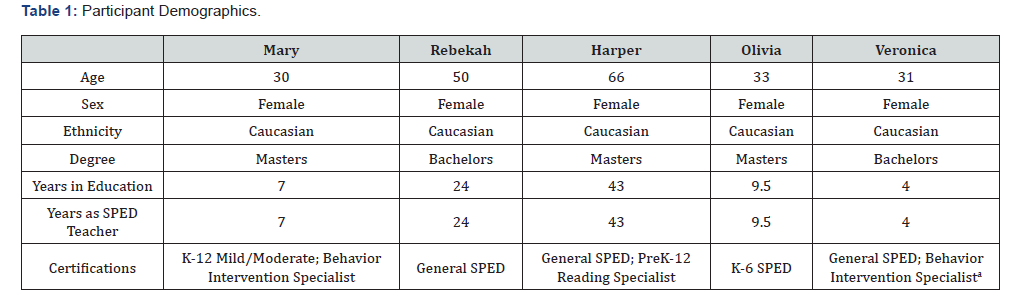

Five participants were recruited via email using purposive sampling. The principal investigator emailed three in a Midwest state and asked them to share a recruitment email about the study with their special education teachers. Interested participants then contacted the principal investigator for more information. Four of the participants were recruited this way while the fifth participant heard about this study from a colleague, was interested in the topic, and wanted to participate. The five in-service special education teachers were employed at different schools in a midwestern state. Their demographic information is in Table 1.

In terms of the setting, all study activities took place using the free public use version of Canvas (www.instructure.com/ canvas), an online learning management system. Participants used their personal computer and internet to access the Canvas website. Participants were encouraged throughout the study to use a computer with a monitor rather than a tablet or cell phone device to access Canvas to ensure they could reliably view graphs and materials. Sessions were conducted once or twice a week for a total of 16 weeks, and participants completed all tasks while working in schools during their regular school year.

Materials

Materials used in this study included a participant demographic questionnaire containing the data in Table 1, graphed data, a prerecorded video, a decision guide, a post-study questionnaire, and a Canvas course shell. The graphed data including how they were generated and selected. The prerecorded video focused on the CDC method as well as the decision guide.

Graph Generation

We used AB-style graphs for our experiment. Our selection of AB-graphs was intentional for multiple reasons. First, this format for graphing data was comparable to other studies that used training with the CDC method to improve visual inspection skills, Our rationale for conducting this study includes expanding the literature on training in the CDC method with a new population of users (i.e., special education teachers), and we felt it was important to maintain some consistency with prior research. Second, we chose AB-graphs because special education teachers are likely to use this form of graphed data in their professional work over other single-case designs. Progress monitoring for academic or behavior skills typically use AB-graphs to evaluate student progress. Thus, we wanted to include AB-graphs in our experiment as they would likely be used by the experiments in their everyday work. Last, we wanted to minimize confounding variables in our study. If we used multiple types of graphs (i.e., AB, multiple baseline, or reversal designs), each would require different trainings to properly use the CDC method. Since we wanted to expand on prior research and use graphed data that was familiar to special educators, we opted to use AB-graphs rather than other formats to test our hypotheses.

AB-graphs were created using predetermined data parameters similar to those in prior research (. SAS OnDemand For Academics Version 9.4 was used to generate 200 normally distributed datasets with two fixed parameters—mean and standard deviation. Five random data points were generated for the baseline (A) phase and ten random data points were generated for the treatment (B) phase. We chose this standard format (i.e., five baseline points and ten treatment points) to maintain consistency across all graphs and limit confounding variables (i.e., different data points require different thresholds). Also, we found that other researchers used similar amounts of data per phase (see Shepley et al., 2022) and determined that our format was comparable to other studies.

Each dataset had two unique features: (1) the presence or absence of a treatment effect, and (2) a behavior pattern of either acquisition (increase) or reduction. Thus, each dataset consisted of 15 data points and demonstrated one of four possible outcomes: (a) a treatment effect with an acquisition pattern, (b) a treatment effect with a reduction pattern, (c) no treatment effect with an acquisition pattern, or (d) no treatment effect with a reduction pattern. Half of the datasets were used to generate graphs for the baseline condition while the remaining were used for the post-training condition. (To avoid ambiguity, the period following participants’ training is referred to as the “post-training condition” instead of the “treatment condition”).

The mean value of each baseline dataset was fixed at 50 while the mean value of the post-training condition was modified in accordance with the intended result (i.e., presence or absence of a treatment effect). For datasets with a treatment effect, the posttraining mean value was fixed to 1.0 SD greater or less than the baseline mean value (i.e., 60 for acquisition datasets and 40 for reduction datasets). For datasets with no treatment effect, the post-training mean value was fixed to 0.5 SD greater or less than the baseline mean value (i.e., 55 for acquisition datasets and 45 for reduction datasets). In order to mitigate the impact of outliers and excessive patterns of variability, the standard deviation of each dataset was constrained to 10 for both baseline and posttraining conditions.

Each graph was evaluated using CDC lines to determine whether it was an accurate representation of a predetermined outcome (i.e., treatment effect or no treatment effect). To do this, each dataset was manually inserted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that generated AB-graphs with the capacity to superimpose CDC lines. Datasets that failed to satisfy the designated CDC criteria were marginally adjusted and reevaluated to ensure their suitability for application. Data were then graphed on Microsoft Excel and saved as a PNG image. Graphs generated for the baseline condition did not include CDC lines, whereas graphs assigned to the post-training condition included them. A brief phrase at the top of each graph specified the desired outcome of the treatment (”Goal: Acquisition” or “Goal: Reduction”). AB-graphs were also generated for the training condition and included CDC lines. Since these graphs were used for the training condition, each one was hand-tailored to meet specific criteria while maintaining similar characteristics to the other datasets (e.g., baseline mean value of 50). A set of 18 AB-graphs was generated specifically for the training condition, with nine graphs representing acquisition (improvement) of skills. and nine graphs representing reduction of behavior. In total, 218 AB-graphs were utilized for the current investigation.

Graph Selection

The “quiz” function on Canvas was used to generate assessments that measured the dependent variable. Graphs belonging to their respective condition (i.e., baseline training, or post-training) were randomly selected using a random number generator on Microsoft Excel and inserted as quiz questions. Each quiz included ten graphs: five demonstrating the presence of a treatment effect (increase of decrease) and five demonstrating the absence of a treatment effect. To prevent practice effects, no participants received back-to-back assessments that included the same graphs. The graphs were then uploaded on a Canvas quiz for participants to complete. A separate Excel spreadsheet was created to monitor the graphs selected for each quiz. The selection process was different for graphs in the training condition with six graphs for the training quiz (three demonstrated treatment effects, and three illustrated null treatment effects). Since these graphs were created for teaching purposes, we created them separately from the others but maintained similar features (i.e., 15 data points, AB-graph design, etc.) for consistency.

CDC Method Instructional Video

A 20-minute video was recorded demonstrating how to accurately interpret graphed data using the CDC method. Slides created with Microsoft PowerPoint were used to present content information which came from guidelines The video was divided into two sections. The video first began with a brief introduction to AB-style graphs (i.e., understanding AB-graphs, identifying baseline and treatment phases) while the second part provided instruction and modeling of the CDC method including the process of how to read CDC lines generated graph correctly and determining if the graph demonstrated the presence or absence of a treatment effect. The video capture platform YuJa (https:// www.yuja.com/) was used to record content for the instructional video, and a unique website link was provided on Canvas for participants to view it.

CDC Decision-Making Guide

A one-page reference guide with CDC decision rules was created by the first author. This guide included a reference table, which is necessary when detecting treatment or null treatment effects using CDC lines, and was viewable as a PDF file.

Post-Study Social Validity Questionnaire

The post-study questionnaire was an adapted version of the social validity questionnaire used by Wolfe et; [15] Slight modifications in wording on items were made to reflect the tasks associated with this study and the CDC training process. The questionnaire was also adjusted to use a six-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Slightly Disagree, 4 = Slightly Agree, 5 = Agree, 6 = Strongly Agree), and three optional openended questions were added after the last Likert scale item. The advantage of using a six-point Likert scale is that it increases the measurement’s precision and reliability [26-28] because there is no mid-point at which participants could defer as there would be in a five-point scale (i.e., 3).

Canvas Course

The Canvas course was divided into three learning modules: (1) activities for the study’s baseline condition, (2) training condition, and (3) post-training condition. Canvas settings were changed to hide participants’ ability to view their grades (i.e., study results) except for during the training condition. All AB-graphs were stored on Canvas in “question banks” for easy retrieval during the study conditions. Each graph was transferred to Canvas and placed as a quiz question. At the bottom of each graph, the phrase “Please look at the graph. Did a treatment effect occur?” was written in bold font. Canvas quiz features were used to generate a dichotomous response option (i.e., “yes” or “no”). For the training quizzes, the same directions were given except that detailed responses regarding the accuracy of the decision were provided for each response to present immediate corrective feedback on response items, which was an important component to the virtual training used in the present study.

When a user selected a correct response on a training quiz, a written description of why the response was correct was immediately provided. Similarly, if a user selected an incorrect response, a written description of why it was incorrect and the rationale for the correct decision was provided. This allowed participants to receive immediate feedback on the correct thinking required for each answer and ensure their correct use of the CDC method prior to advancing into the post-training condition of the study.

Dependent Variable

The proportion of accurate decisions per assessment served as the dependent variable. This variable was measured by the participants’ response choice (i.e., “yes” or “no”) to the prompt “Please look at the graph. Did a treatment effect occur?” The percentage of correct responses per assessment was divided by the total number of questions (i.e., 10 per session) and multiplied by 100 (range = 0% - 100%). Interobserver agreement was not necessary to calculate because participant responses were recorded digitally and, consequently, not subject to human errors.

Independent Variable

Virtual training of the CDC method was the independent variable for this study. Training consisted of two parts: (1) participants viewed the CDC Method Instructional Video and gained access to the CDC Decision-Making Guide after watching it and (2) participants completed a six-question Canvas training quiz that assessed their application of the skills taught in the training video.

Procedures

Participants were instructed via email to create a free Canvas account by registering and entering their email address. Each participant received an individualized Canvas learning page that did not share any items or materials with another participant’s page. Thus, five individual Canvas learning pages were monitored throughout the duration of the study. The Participant Demographic Form was sent via email to each participant who completed the form and returned it via email within two weeks of initial contact.

In general, each session was one week for either baseline or post-training conditions and participants were required to complete three Canvas quizzes, each of which took approximately 10-15 minutes. In the training condition, a session included successful completion of the virtual training activities (i.e., instructional video and quiz) which took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Email was used to communicate with each participant every week throughout the study. As needed, followup emails were sent to ensure participants completed their weekly tasks in a timely manner.

Baseline Condition

During baseline participants completed three Canvas quizzes per session. The principal investigator published the phase one module and quizzes needed to be completed for that session. Quiz instructions directed participants to complete each item using their best effort. Each item on the quiz was displayed one at a time, and participants could backtrack to previous questions to ensure the best attempt for each quiz. Also, they did not have access to any resources (e.g., graphs with CDC lines, reference guides) or feedback during their time in the baseline condition. Each participant’s data was monitored for stability across baselines. Two sessions (i.e., six quizzes) were administered prior to the first participant receiving the virtual training of the CDC method.

Training Condition

Participants were given access to the phase two training condition which included a link to the CDC Method Instructional Video, a downloadable copy of CDC Decision-Making Guide, and a Canvas six-item training quiz. Each participant watched the instructional video in its entirety before receiving access to the decision-making guide. Once the video was completed and the decision-making guide shared, the participants then completed a training quiz on Canvas. Thus, successful completion of the training required participants to (1) watch the CDC Method Instructional Video, and (2) demonstrate evidence of proficiency by completing the training quiz with at least five correct responses. Data collection of the dependent variable stopped for any participant receiving training, and only one participant was given access to the training condition at a time while the others continued baseline assessments.

When a clear treatment effect was achieved by the first participant after receiving training, the training condition was introduced to the second participant. The trained participant was expected to demonstrate an increase in accurate interpretations of graphed data (i.e., the dependent variable). The other participants were expected to demonstrate a constant (i.e., stable) data pattern at baseline. This procedure continued in a staggered fashion until all participants for whom baseline data were collected received the training.

Post-Training Condition

After a participant successfully completed the training condition, data collection of the dependent variable resumed. The post-training condition was opened on Canvas, and the phase two module was unpublished. Unique to the post-training assessments was the inclusion of graphs that superimposed CDC mean and trend lines on the treatment phase. Participants also had access to the CDC Decision-Making Guide to help them answer each question. It is a required component of the CDC method to know the amount of data points needed to detect a treatment effect from a reference table. Thus, participants were reminded to have the guide in a viewable location while completing the post-training assessments. Similar to baseline, participants were not given any feedback on their performance during their time in the post-training condition. Reteaching of skills was not provided, similar to previous research. As participants entered the post-training condition, data collection continued throughout the study’s duration (i.e., assessments did not stop until the final session was completed). Visual analysis was used to determine when the study ended, with all participants displaying a clear pattern of performance while in the post-training condition.

Post-Study Questionnaire

The social validity post-study questionnaire was opened one week after the final post-training session of the last participant on Canvas. All participants completed this questionnaire within the week it was initially published.

Data Analysis

Four methods were used to analyze data: VA, CDC structured criteria, effect size calculations, and descriptive statistics. This approach provided for the most comprehensive analysis of treatment effectiveness.

Visual Analysis (VA)

VA was accomplished through a graphed depiction of the dependent variable. The percentage of accurate responses was displayed on a line graph for each participant. A treatment effect was detected when there is a marked change in the level, trend, or variability of the dependent variable within and across experimental conditions. Since the goal of the present study is to increase decision-making accuracy of visually interpreting graphed data, an appropriate demonstration of this goal is if the percentage of correct responses were consistently high (i.e., > 80%) during the post-training phase, or if the increase in the data pattern is only seen after the staggered introduction of the virtual training across participants.

Structured CDC Method

The structured CDC method was also used to determine if a treatment effect occurred within participants. Using the most updated guidance participant performance was compared to the CDC calculations and graphed. This is feasible only when data collected at treatment is between five and 23 observations—there currently are no decision-making criteria beyond 23 observations However, given five participants, and the length of time the first three will be in the post-treatment phase, a modification was undertaken in case any had over 23 data points to calculate CDC lines for the purpose of treatment efficacy. Specifically, any participants over 23 data points in the post-treatment phase would have 23 randomly selected data points five times and CDC lines will be calculated for each of the five sets. The idea is that if 23 randomly selected data points calculated five times came up with the same results, then this procedure may portend a new way to use the CDC method with more than 23 data points in intervention (or post-intervention in the current study).

Effect Sizes

Two types of effect sizes were calculated. The first was the baseline corrected Tau-U statistic [29]. This statistic represents the proportion of data that improved between baseline and interventions phases after controlling for baseline performance (i.e., monotonic trend). Baseline corrected Tau-U values range from -1.0 to 1.0, with values above 0.9 considered large, values between 0.6 to 0.9 are moderate, and values below 0.6 are small. The benefit of this type of effect size is that it controls Type I error better than the traditional Tau-U statistic and is bound between conventional limits (i.e., -1.0 to 1.0).

In order to have a statistical metric of magnitude of change, which non-overlap effect sizes do not capture, the Log Response Ratio (LRR) was calculated which is a within-case effect size estimator [30]. The effect size index calculates the magnitude and direction of treatment effects in terms of proportionate change from the baseline to the intervention phase for individual cases [31] Negative LRR values correspond with decreasing change, positive values correspond with increasing change, and values of zero correspond to no change.

Social Validity

The post training questionnaire was analyzed using two methods. For the Likert-scale items, descriptive statistics were used to capture the average score and range from all participants. This is like the method used by Wolfe et al; [15]. Higher scores represent stronger evidence of the CDC method as a socially acceptable tool. The descriptive statistics were analyzed in conjunction with the summaries of the responses to the openended questions.

Results

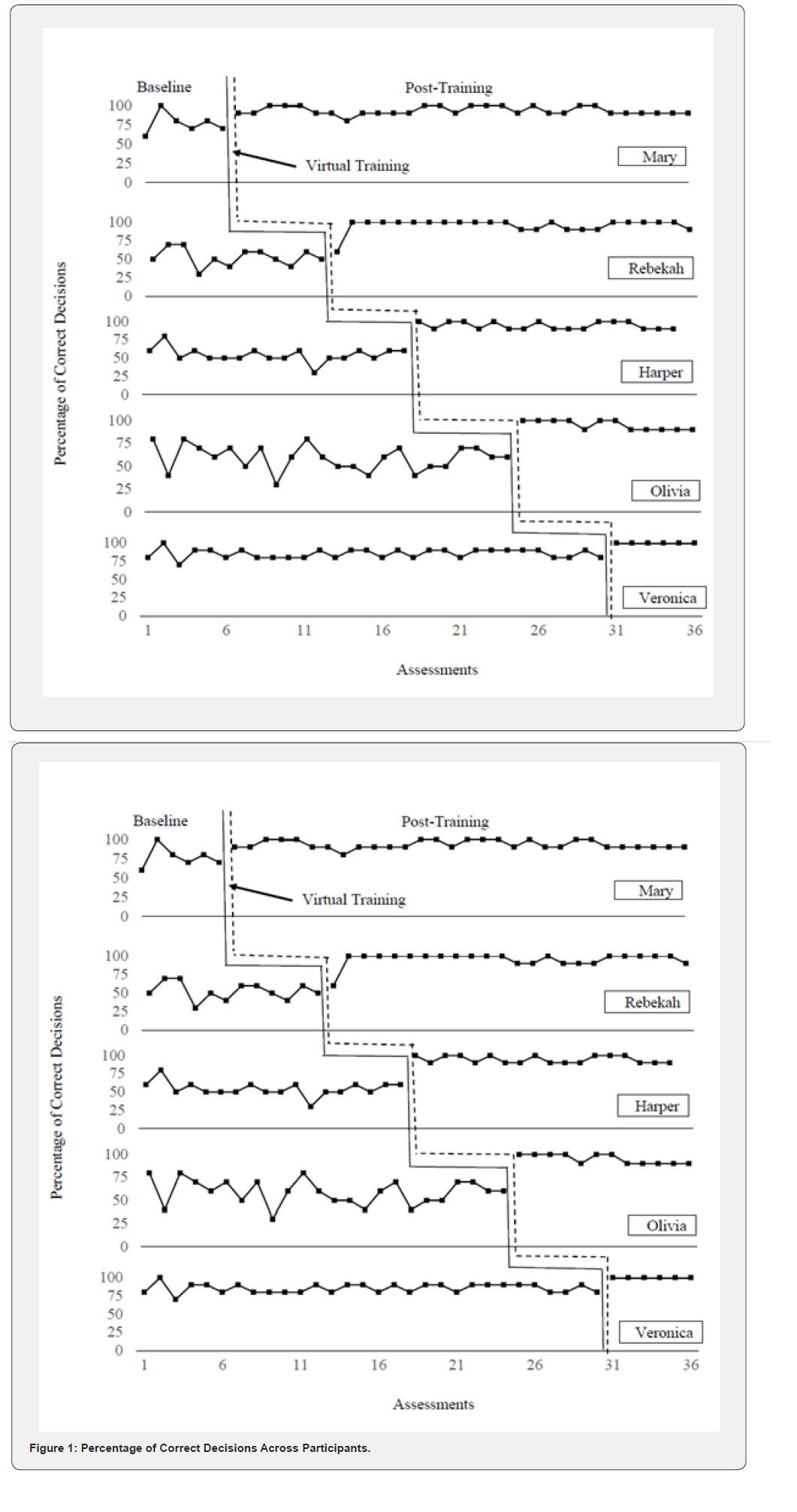

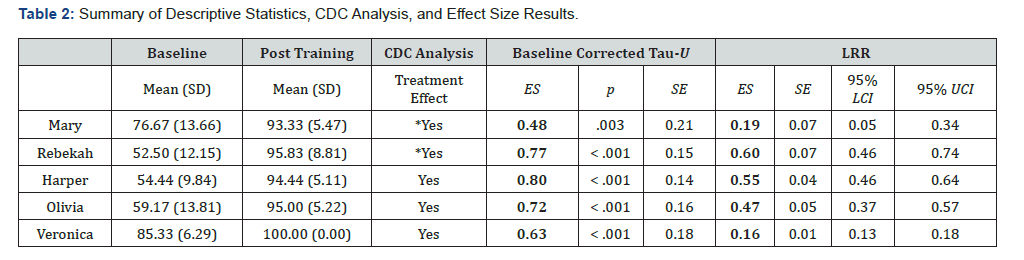

Participants’ graphed results appear in Figure 1 and their descriptive statistics including CDC analyses and effect sizes in Table 2. Participants Mary and Rebekah had over 23 data points during post-treatment which resulted in using the novel procedure described previously.

VA and Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive results are organized into three sections: (1) baseline patterns, (2) training assessment, and (3) post-training outcomes, which assessed participants’ ability to use the CDC lines independently and accurately.

Baseline Patterns

Stable baselines were achieved for all participants. The average percentage of correct decisions during the baseline condition differed across participants (M = 67.22, SD = 17.48), with scores ranging from 52.50 to 85.33. Mary and Veronica’s performances were above-average compared to the other participants. Mary’s performance exhibited stability with the exception of a single spike, which occurred when she achieved a perfect score on the second assessment. Despite Veronica remaining at baseline for the longest period of time, her performance remained relatively consistent. Olivia’s baseline performance displayed the most variation, with her decision-making accuracy varying between 30% and 80%. Although Harper’s baseline scores did not fluctuate to the same extent as Olivia’s, they still demonstrated similar performance characteristics, with a range of 30% to 80%. Rebekah’s baseline scores were slightly different (range 30% to 70%) and exhibited little variation.

Training Assessment

All participants successfully completed the training assessment in one attempt, with the minimum requirement for passing being five correct decisions (i.e., 83%). Two participants (Mary and Harper) completed the training with 83% accuracy, and three (Rebekah, Olivia, and Veronica) completed the training with 100% accuracy. Each participant completed the virtual training (i.e., video and assessment) within five days after it was published on Canvas.

Post-Training Patterns

The average percentage of correct decisions made independently using the CDC method during the post-training condition was noticeably higher than at baseline (M = 94.89, SD = 6.40), with scores ranging from 93.33% to 100%. Mary’s scores were stable and between 80% to 100%. Her lowest score (80%) only occurred once. Similar to Mary, Rebekah achieved her lowest score (60%) on a single occasion, whereas all other evaluations were markedly higher (i.e., 90% to 100%). Harper’s scores remained consistent and never fell below 90%. Compared to baseline, Olivia’s performance markedly stabilized and improved during the post-training condition while Veronica showed perfect accuracy. These changes were immediate and observed in all participants only after the virtual training was completed Figure 1. Based on the observed improvements in decision-making accuracy among all participants following the virtual training, and the stable baseline performances of subsequent participants, these results indicate that experimental control was achieved.

CDC Method Analysis and Effect Sizes

The CDC method, which is basically a visual version of nonoverlapping effect sizes, was used to analyze whether the virtual training produced a marked increase in the decisionmaking accuracy for all participants—Harper, Olivia, and Veronica using the Swoboda et al; [22] guidelines while Mary and Rebekah’s CDC lines were calculated using the novel procedure described previously. Specifically, SAS OnDemand for Academics Version 9.4 was used to randomly select 23 data points from Mary and Rebekah’s post-training performances using the PROC SURVEYSELECT procedure five times each. Subsequently, each dataset was assessed for treatment effects utilizing the CDC method and in relation to the participant’s baseline performance. CDC analyses reflected that their correct responses after receiving virtual training clearly exceeded baseline performance indicating that the virtual training produced a marked increase in decisionmaking accuracy (i.e., treatment effect).

Two effect sizes were also calculated to analyze the data Table 2 lists the results for the baseline corrected Tau-U statistic and LRR effect size for each participant. The baseline-corrected Tau-U effect sizes ranged from 0.48 to 0.80 and represented small to moderate effects. Each effect size was found to be statistically significant, suggesting that the performances across baseline and treatment conditions within participants were markedly different. LRR effect sizes were also found to be statistically significant for each participant, ranging from 0.16 to 0.60. Each LRR effect size was then converted as a percent change from baseline to treatment conditions. Mary increased by 21% (95% CI [5%, 40%]), Rebekah by 82% (95% CI [59%, 109%]), Harper by 73% (95% CI [59%, 89%]), Olivia by 60% (95% CI [45%, 77%]), and Veronica by 17% (95% CI [14%, 20%]).

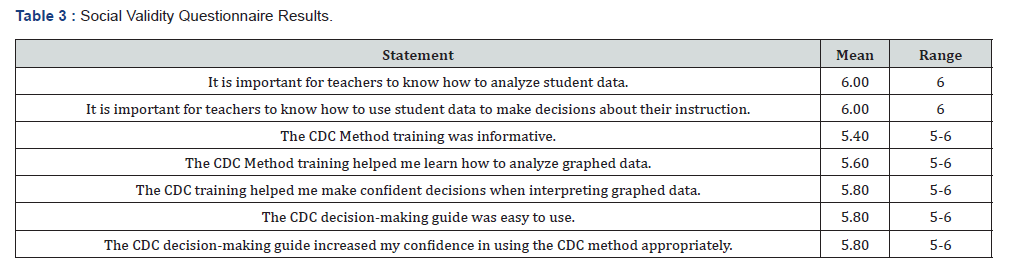

Social Validity

The aggregated results from the social validity Likert-scale items are presented in Table 3, accompanied by descriptive statistics. As a whole, participants agreed that it was crucial for teachers to analyze student data and utilize the results to inform instructional decisions. The training video and decision-making guide were both perceived as useful and informative resources by all participants.

The questionnaire also included three open-ended questions. The first question asked participants to comment on what they liked about the CDC training. All five participants responses to this question reflected a general theme was the ability to use the CDC method to analyze and share data more effectively. The second question asked for any remaining questions related to the CDC training. One participant responded with a request for assistance with CDC line creation in order to analyze her own student data. The third open question asked participants to identify the advantages of employing the CDC method when examining graphed data in the role of a special educator. All five participants’ answers reflected one main theme: employing the CDC method would enhance their ability to effectively analyze and utilize student data for purposes such as progress monitoring and assessing the efficacy of interventions.

Discussion

This study explored whether the utilization of virtual training on the CDC method could enhance decision-making accuracy among special education teachers during the analysis of graphed data. Using a multiple baseline design across participants, five in-service special education teachers completed the training and applied the skills to researcher-generated graphs during subsequent sessions. Results indicated that the virtual training improved the accuracy of interpreting graphed data across all participants, with small to moderate effects. Further, in relation to their professional needs, participants regarded the virtual training as socially acceptable. The discussion of the current investigation’s results is divided into four focus areas: (1) a closer look at Mary and Veronica’s data, (2) the present study’s contribution to existing literature, (3) practitioner considerations, and (4) limitations and future research.

Mary and Veronica

It is interesting to note that Mary and Veronica’s decisionmaking accuracy during baseline was noticeably better than the baseline performances of other participants. Serendipitously, both indicated they had received formal training as behavior intervention specialists. This training might explain their aboveaverage performances. Special education teachers with additional training as behavior interventionists typically have advanced knowledge about monitoring and evaluating the efficacy of interventions [32]. This information includes the ability to read and interpret graphed data for the purpose of knowing an intervention’s effect on student behavior [33]. It is probable that their background helped them read the baseline graphs more accurately than other participants. However, despite their professional backgrounds and baseline performances, both showed marked improvements in their decision-making accuracy after receiving the virtual training. This effect demonstrates that the CDC method can enhance the decision-making accuracy skills of special education teachers with advanced training or expertise in examining graphed data.

Efficacy of the CDC Method

This study expanded prior research concerning the efficacy of the CDC method for enhancing professionals’ decision-making accuracy when interpreting graphed data. In both of those studies, the researchers used a short (i.e., 10-15 minute) presentation to teach the CD and CDC methods, respectively, to participants. Soon after receiving the presentation, participants in both studies demonstrated a marked increase in their ability to accurately interpret graphed data.

The present study, using a similar design and training approach, revealed similar results. Soon after each of the five participants received the virtual training on the CDC method, results noticeably increased across all participants and remained constant throughout the duration of the study. Although the present study exhibits similarities to those of it distinguishes itself in two ways. First, this study is a novel attempt to examine whether knowledge and application of the CDC method benefit in-service special education teachers. In terms of both practical usefulness (i.e., social validity) and decision-making precision, the outcomes demonstrated that the CDC method is advantageous. Second, this study used Canvas to store all study materials and activities, thus making it accessible to a wider audience through the use of an online learning management system. Despite the changes in setting, the present study’s results—the immediate and sustained improvement of decision-making accuracy when interpreting graphed data—were comparable to prior research. This study expands the body of literature supporting the CDC method as an effective approach to enhance professionals’ accuracy in interpreting graphed data.

Effect Sizes in Single Case Design

The present study calculated two effect sizes—the baseline corrected Tau-U and LRR—for each participant. Findings revealed that the effect sizes were noticeably different. For example, when using the baseline corrected Tau-U, Harper (ES = 0.80) showed the largest post-training effect across participants. However, when using the LRR, Rebekah demonstrated the largest effect magnitude among participants with an 82% change across experimental conditions. Moreover, Veronica’s LRR (17% change) and baseline corrected Tau-U (ES = 0.63) effect size calculations seem more different than they are alike. This begs the question— which effect size most accurately describes the data?

Ledford et al; [34] noted that an effect size metric needs to be meaningful and interpretable for the interventions and dependent variables studied in single-case designs. Researchers are advised to select effect sizes that are compatible with the dependent variable used and the objectives of the study. For example, Ledford, et al [34] noted that it is inappropriate to use the LRR effect size statistic for studies where the target behavior is absent, or nearly so, during baseline. This conclusion is because the absence of the target behavior at baseline nullifies the value of calculating the dependent variable’s percentage change across experimental conditions. Conversely, the LRR is appropriate in situations where there is evidence of the target behavior at baseline and the goal of the intervention is to change its occurrence (e.g., 50% reduction in aggressive behavior).

For the present study, the LRR effect size appears to be a more meaningful statistic than the baseline corrected Tau-U for three reasons. First, the dependent variable (i.e., percentage of correct decisions) uses a ratio scale that the LRR can calculate as a percentage change across conditions. Second, based on the purpose of the current study, it is more advantageous to know the magnitude of change that occurred across experimental conditions rather than calculating the proportion of nonoverlapping data. In other words, knowing the degree to which decision-making accuracy improved within each participant after completing virtual training on the CDC method is more valuable than knowing whether the proportion of non-overlapping data between experimental conditions was significant. Third, each participant demonstrated some level of decision-making accuracy when interpreting graphed data before receiving the virtual training. Thus, capturing the percentage change in decisionmaking accuracy that occurred after the virtual training was appropriate. Future educational research using single-case designs to examine teacher skill development may benefit from utilizing the LRR effect size because of its capacity to meaningfully calculate changes across experimental conditions for skills that are likely present prior to implementing a training or intervention. The current investigation illustrates the importance of aligning the use of effect sizes in single-case design to the purpose of the study and the statistical characteristics of its assessments.

Another point related to effect sizes was calculating CDC lines/results for Mary and Rebekah, who were the first two tier participants which resulted in their post-training data to exceed 23 data points that previously was “incalculable” due to limitations in the most updated guidance on the CDC method. This limitation is perplexing because, tacitly, it should not matter how many data points are in the post-baseline phase. Further, calculating CDC lines to corroborate results of a study are not unlike nonoverlap effect sizes since data is looking for a number of points either above or below the superimposed mean and trend lines. Nevertheless, one way to adhere to the 23 data point maximum was to randomly generate 23 data points of post-training for Mary and Rebekah which was repeated five times using a random number generator. Results were the same as for the other three participants whose post-training data did not exceed 23 points. Consequently, this is the first study to use this approach to calculate CDC results.

Social Validity

The current investigation is the first to measure special education teachers’ acceptability of using the CDC method [35] conceptualized social validity using three criteria: (1) social significance of the goals (i.e., the importance of making accurate decisions when interpreting graphed data), (2) social appropriateness of the procedures (i.e., the quality of the training video and CDC decision-making guide), and (3) social importance of the effects (i.e., the benefits of using the CDC method as a practitioner). Overall, the findings from the present study were promising. All five participants rated the virtual training and activities as socially acceptable (ratings of “agree” or “strongly agree”).

This result implies that educators in special education could enhance their decision-making accuracy immediately after completing a brief (20-minute) virtual training on the CDC method, while also perceiving the activities as beneficial and pertinent to their professional responsibilities without requiring an inordinate amount of time. Furthermore, it is noteworthy to recognize that this training took place throughout the academic year and yielded favorable outcomes without demanding a substantial investment of time or resources.

Evaluations of social validity may also be crucial in determining whether teachers will adopt particular interventions or strategies in their classrooms. For example, McNeill; [36] surveyed 130 special education teachers and found that socially acceptable instructional strategies and interventions were more likely to be used in classrooms than activities with low social acceptability ratings. Although the present investigation did not evaluate the practical application of the CDC method in the classroom, it is encouraging to observe that special education teachers possess the ability to gain expertise and effectively employ the CDC method, while also regarding it as a socially acceptable practice.

Implications for Practice

There are two important implications for practice from the current investigation. First, the present study further corroborates the idea that teachers may benefit from straightforward and specific task-oriented professional development. It was hypothesized that changing teacher procedural classroom behavior, such as instructional routines, is easier than improving teacher content knowledge. In the present study, the focus was to train special education teachers on specific tasks related to graph interpretation. Using the CDC method as the framework to detect treatment effects, the virtual training outlined, step-by-step, the actions needed to make accurate interpretations of graphed data. The training and decision-making guide placed less emphasis on the requisite subject matter expertise for accurate graph analysis and more on the specific decision-making skills necessary to achieve the same goal. In essence, the CDC method simplified the process of interpreting graphed data.

This finding is not surprising. A study by Wolfe et al; [36] surveyed researchers with extensive experience and expertise in visual inspection. They were shown graphs and asked to make a judgment on whether the dependent variable changed across experimental conditions. The same set of graphs was also analyzed by researchers using the CDC method for detecting treatment effects. They then compared results of expert raters with the outcome calculated by the CDC method. Wolfe and colleagues found that when expert visual analysts agreed about the presence or absence of change, the CDC method was likely to compute a similar outcome. Thus, Wolfe and colleagues proposed that novices (i.e., non-experts) could be trained to assess data patterns in a manner comparable to that of experts by utilizing the CDC method. Without requiring practitioners to be subject matter experts, the current study provides support for the idea that straightforward, task-oriented training can improve professional skills (e.g., correct interpretations of graphed data) in special education teachers.

Second, the current study demonstrated that special education teachers have the capacity to acquire knowledge regarding a method (i.e., the CDC process) that could be used to enhance their DBDM capabilities when interpreting CBM data. Interpreting CBM data correctly is an important skill. However, the decision rules and techniques typically associated with CBM graph interpretation may not be reliable. For example [37] examined the diagnostic accuracy associated with decision making as it is typically applied to CBM data. They simulated 20,000 progressmonitoring data sets and analyzed five CBM data point decision rules (i.e., 3-, 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-point rule) for determining whether a student is making adequate progress compared to an aim line. Hintze and colleagues found that the commonly used 3- and 4-point decision-making rules lead to unrealistically high levels of false positives, which may result in the unnecessary alteration of an effective intervention. They suggested utilizing at least five or six consecutive data points to reduce decision-making errors.

The CDC method may benefit practitioners by improving their CBM graph interpretation skills in two ways. First, the CDC method requires that at least five data points be recorded in the treatment condition prior to making any judgment on the presence or absence of a treatment effect. This condition aligns with Hintze and colleagues’ recommendation for a more conservative decision-making rule to detect intervention effects. Furthermore, in order to identify treatment effects in CBM data, the CDC mean and trend lines may be employed as supplementary criteria. Integrating the CDC method with CBM data decision-rules may be a useful way to improve DBDM skills in special educators. The present study demonstrates that special education teachers can learn the CDC method and successfully apply it to graphed data; further investigation is warranted to explore its potential in CBM programs.

Last, and on a lighter note, our study demonstrated that special education teachers have the capacity to improve their visual inspection skills after completing virtual training on the CDC method while working their full-time jobs as an educator. This study was conducted during the regular school year, and participants were instructed to complete all activities on their own time. Though we did not analyze the unique learning patterns of each participant (i.e., capturing when or how long they completed specific tasks), we did find outcomes suggesting that the training improved their ability to accurately interpret graphed data. Our study corroborates with other research suggesting that simple interventions can have a positive impact on teachers’ DBDM skills [38].

Limitations and Future Research

This study is not without limitations. First, the present study did not conduct a component analysis of the virtual training package. We did not account for the unique effects of either the online training video or the decision-making guide in our analysis. Although there is evidence suggesting that the use of both resources (i.e., training video and guide) improved accurate interpretations of graphed data it is unclear whether both were needed. It is possible that the efficacy of the tools is conditional and influenced by other teacher characteristics, such as teacher experience or confidence [39] examined the impact that teacher training, experience, and confidence had on teacher graph literacy by using structural equation modeling on data collected from 309 teachers. They found that experience and confidence predicted teacher graph literacy, but training did not. Training did, however, predict teacher confidence. These findings point to the possibility that teacher graph literacy is a multifaceted learning experience and that some practitioners may require different resources to achieve similar outcomes. Future research should investigate whether providing the CDC decision-making guide or training video, exclusively, lead to similar outcomes in special education teachers.

Second, data used for creating graphs were simulated based on fixed statistical parameters and assumptions. Although graphs generated for this study were created to resemble student data, they were not based on actual student data. Future research on the CDC method could include datasets that use or simulate real student data across different content areas. Since special education teachers read and interpret graphed data in multiple contexts (i.e., academic performance, behavior modification, etc.), the benefit of this adaptation is that it closely mirrors the real experiences of practitioners and can further investigate the usefulness of the CDC method in applied situations.

Third, each graph was generated with consistent features in the baseline and treatment phases (i.e., data points per phase). This constant may have inadvertently inflated respondent performance. In order to use the CDC method properly, one must count the number of data points in the treatment phase and use a reference table to determine whether a treatment effect occurred. Thus, as the number of data points in the treatment phase increases, the criteria for detecting treatment effects change. For example, in order to detect a treatment effect with 10 total data points in the treatment condition, eight or more of them need to be above or below the CDC lines for a treatment effect to be evident.

In cases where there are 15 total data points in the treatment condition, the criteria for detecting a treatment effect change from eight points to 12. Since all graphs used in this study recorded 10 data points in the treatment phase, respondents consistently looked at a single reference point when using the decision-making guide. The number of data points in the treatment phase rarely remains the same when observing behavior or tracking academic performance across different individuals. Thus, future research on the CDC method should require respondents to evaluate graphs that have different baseline and treatment characteristics, such as total data points per phase. This arrangement compels respondents to be more cognizant of individual graph characteristics, thereby enhancing the evidence about their ability to employ the CDC method suitably.

Also, it is fitting to note that we did not require participants to create their own CDC lines. Rather, the lines were superimposed on the post-training graphs. Thus, another area for future research is to provide teachers with a simple-to-use method for creating CDC lines. Currently, the most common method is to have a preformatted Excel document. Pre-formatting an Excel document for superimposing CDC lines is not particularly difficult. However, most school districts have restrictions on the types of programs teachers can have on their work computers as well as frequently having their own graphing process or program that may not be amenable for creating and superimposing CDC lines. This topic would be one of great interest given the empirical advantages of using CDC lines to accurately interpret graphed data.

Fourth, this study defined treatment effects solely based on the structured format of the CDC method. There are other factors that contribute to treatment effects, such as intervention fidelity and a student’s learning environment, to name a few. The intent of the present study was to evaluate a systematic approach for training the CDC method with special education teachers. Future research may consider creating vignettes that describe the “story behind the data” and incorporating those descriptions as part of the analysis of graphed data. Additional investigation into the efficacy of the CDC method in such conditions strengthens its potential utility.

Conclusion

Overall, these findings indicate that virtual training on the CDC method improved the decision-making accuracy of inservice special education teachers when interpreting graphed data. The teachers found this training to be useful, informative, and practical for their professional duties. It is important to remember that research only benefits students when it is applied in the classroom by teachers [40]. The present study provides evidence that special education teachers can use the CDC method accurately and consistently. However, more work should be done to ensure that special education teachers obtain the DBDM skills necessary to improve student outcomes. Using the CDC method could be one approach to achieving this objective.

References

- Kearns DM, Feinberg NJ & Anderson LJ (2021) Implementation of data-based decision-making: Linking research from the special series to practice. Journal of Learning Disabilities 54(5): 365–372.

- Jung PG, McMaster KL, Kunkel AK, Shin J & Stecker PM (2018) Effects of data-based individualization for students with intensive learning needs: A meta-analysis. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 33(3), 144–155.

- Deno SL & Mirkin PK (1977) Data-based program modification: A manual. Council for Exceptional Children.

- Espin CA, Wayman MM, Deno SL, McMaster KL, & de Rooij M (2017) Data‐based decision‐making: Developing a method for capturing teachers’ understanding of CBM graphs. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice 32(1): 8–21.

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Hamlett CL & Stecker PM (2021) Bringing data-based individualization to scale: A call for the next-generation technology of teacher supports. Journal of Learning Disabilities 54(5): 319–333.

- Lemons CJ, Kearns DM & Davidson KA (2014) Data-based individualization in reading: Intensifying interventions for students with significant reading disabilities. TEACHING Exceptional Children 46(4): 20–29.

- Powell SR & Stecker PM (2014) Using data-based individualization to intensify mathematics intervention for students with disabilities. TEACHING Exceptional Children 6(4): 31–37.

- Deno SL (2003) Developments in curriculum-based measurement. Remedial and Special Education, 37(3): 184–192.

- Swain KD & Hagaman JL (2020) Elementary special education teachers’ use of CBM data: A 20-year follow-up. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 64(1): 48–54.

- Hosp MK, Hosp JL & Howell KW (2016) The ABCs of CBM: A practical guide to curriculum-based measurement (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- van den Bosch RM Espin CA, Chung S & Saab N (2017) Data‐based decision‐making: Teachers’ comprehension of curriculum‐based measurement progress‐monitoring graphs. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice 32(1): 46–60.

- Shepley C, Lane JD & Graley D (2022) Progress monitoring data for learners with disabilities: Professional perceptions and visual analysis of effects. Remedial and Special Education 44(4): 283–293.

- Lane JD & Gast DL (2014). Visual analysis in single case experimental design studies: Brief review and guidelines. Neuropsychological rehabilitation 24(3-4): 445-463.

- Lane JD, Shepley C & Spriggs AD (2021) Issues and improvements in the visual analysis of AB single-case graphs by pre-service professionals. Remedial and Special Education 42(4): 235–247.

- Wolfe K, McCammon MN, LeJeune LM & Holt AK (2023) Training preservice practitioners to make data-based instructional decisions. Journal of Behavioral Education 32: 1–20.

- Gesel SA, LeJeune LM, Chow JC, Sinclair AC & Lemons CJ (2021) A meta-analysis of the impact of professional development on teachers' knowledge, skill, and self-efficacy in data-based decision-making. Journal of Learning Disabilities 54(4): 269–283.

- Stewart KK, Carr JE, Brandt CW & McHenry MM (2007) An evaluation of the conservative dual‐criterion method for teaching university students to visually inspect AB‐design graphs. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 40(4): 713–718.

- Wolfe K & Slocum TA (2015) A comparison of two approaches to training visual analysis of AB graphs. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 48(2): 472–477.

- Young ND & Daly EJ (2016) An evaluation of prompting and reinforcement for training visual analysis skills. Journal of Behavioral Education 25: 95–119.

- Fisher WW, Kelley ME & Lomas JE (2013) Visual aids and structured criteria for improving visual inspection and interpretation of single-case designs. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 36(3): 387-406.

- Jimenez BA, Mims PJ & Browder DM (2012) Data-based decisions guidelines for teachers of students with severe intellectual and developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 47(4): 407–413.

- Swoboda CM, Kratochwill TR & Levin JR 2010 Conservative dual-criterion method for single-case research: A guide for visual analysis of AB, ABAB, and multiple-baseline designs. (WCER Working Paper No. 2010-13).

- Dowdy A, Jessel J, Saini V & Peltier C (2022) Structured visual analysis of single‐case experimental design data: Developments and technological advancements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 55(2): 451-462.

- Desimone LM & Garet MS (2015) Best practices in teachers’ professional development in the United States. Psychology, Society and Education 7(3): 252–263.

- Kazdin AE (2020) Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Chomeya R (2010) Quality of psychology test between Likert scale 5 and 6 points. Journal of Social Sciences 6(3): 399–403.

- Leung SO (2011) A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. Journal of Social Service Research 37(4): 412–421.

- Nemoto T & Beglar D (2014) Developing Likert-scale questionnaires. In N. Sonda & A. Krause (Eds.), JALT2013 Conference Proceedings. JALT.

- Tarlow KR (2017) An improved rank correlation effect size statistic for single-case designs: Baseline Corrected Tau. Behavior Modification 41(4): 427–467.

- Pustejovsky JE (2015) Measurement-comparable effect sizes for single-case studies of free-operant behavior. Psychological Methods 20(3): 342–359.

- Common EA., Lane KL, Pustejovsky JE, Johnson AH & Johl LE (2017) Functional assessment–based interventions for students with or at-risk for high-incidence disabilities: Field testing single-case synthesis methods. Remedial and Special Education 38(6): 331–352.

- Farmer TW, Sutherland KS, Talbott E, Brooks DS, Norwalk K, et al. (2016) Special educators as intervention specialists: Dynamic systems and the complexity of intensifying intervention for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 24(3): 173-186.

- Kern L, & Wehby JH (2014) Using data to intensify behavioral interventions for individual students. Teaching Exceptional Children 46(4): 45–53.

- Ledford JR, Lambert JM, Pustejovsky JE, Zimmerman KN, et al. (2023) Single-case-design research in special education: Next-generation guidelines and considerations. Exceptional Children 89(4): 379–396.

- Wolf MM (1978) Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 11(2): 203–214.

- Wolfe K, Seaman MA, Drasgow E & Sherlock P (2018) An evaluation of the agreement between the conservative dual‐criterion method and expert visual analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 51(2): 345–351.

- Hintze JM, Wells CS, Marcotte AM & Solomon BG (2018) Decision-making accuracy of CBM progress-monitoring data. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 36(1): 74–81.

- LaLonde K, VanDerwall R, Truckenmiller AJ & Walsh M (2023) An evaluation of a decision‐making model on preservice teachers' instructional decision‐making from curriculum‐based measurement progress monitoring graphs. Psychology in the Schools 60(7): 2195-2208.

- Oslund EL, Elleman AM & Wallace K (2021) Factors related to data-based decision-making: Examining experience, professional development, and the mediating effect of confidence on teacher graph literacy. Journal of Learning Disabilities 54(4): 243-255.

- Fry EC, Toste JR, Feuer BR & Espin CA (2023) A systematic review of CBM content in practitioner-focused journals: Do we talk about instructional decision-making? Journal of Learning Disabilities. Advance online publication.