- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

When Families Face Social Morphogenesis and Become Relational Goods

Pierpaolo Donati*

Alma Mater Professor of Sociology, University of Bologna, Italy

Submission: December 16, 2022; Published: January 04, 2023

*Corresponding author: Pierpaolo Donati, Alma Mater Professor (PAM) of Sociology at the Department of Political and Social Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

How to cite this article: Pierpaolo D. When Families Face Social Morphogenesis and Become Relational Goods. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2023; 20(2): 556032. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2023.20.556032.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

Abstract

It is common knowledge that social processes are changing the family, so much so that many wonder if it will survive. The thesis of this paper is that the tendencies towards the dissolution of the family are due to processes of morphogenesis which require careful analysis and evaluation. The social morphogenesis of the family can have many meanings and developments. Tendencies towards the family’s dissolution can be, and indeed are, opposed by that part of civil society for which the family is a relational good that generates other relational goods. It is necessary to understand if and where the family (re)generates itself in those primary social networks that escape the processes of chaotic morphogenesis thanks to the vitality of the family’s own social genome. This genome is what makes the family the source of all personal and social virtues, that is, the primary relational goods on which the happiness of individuals depends. It is a question of discovering if and how the germ of a new family life can be born that humanizes people rather than abandoning them to commodification and estrangement.

Keywords: Family; Relational analysis; Social morphogenesis; Relational goods; Humanization

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

In the year 1991, in the face of the arrival of the so-called postmodern era, I wrote, “… everything that happens can be understood as social morphogenesis under conditions of considerable complexity” [1]. This is the theme that I will address here with regard to the family. We have to understand the shape currently being taken by the morphogenesis of the family and how it can be dealt with in order to foster the emergence of a humanizing family rather than an alienating one. Throughout history, the family models legitimated and institutionalized by society have been those spawned by emerging social movements that then established themselves as the vanguard of cultural change, before finding their way to the rest of the population (trickledown effect).

In modern times, this has meant changing popular culture by spreading a certain bourgeois-liberal kind of culture. Innovations in family lifestyles started from the wealthiest social classes and then trickled downwards. This trend is still ongoing, if we look at the way in which a number of phenomena, such as the rejection of marriage, the recourse to divorce, the right to abortion as a means of birth control, the eugenic selection of embryos, the right to change gender identity, and so on, are spreading around the world. The driving force behind changes in the family has always been an individualistic liberalism opposed to social ties, which progressively erodes the primary solidarities of popular life worlds.

For this type of liberalism, only those who fight against all types of ascriptive ties (such as ties of family descent) can access intellectual and political freedom. The general idea is that only individuals freed from family bonds can be the subjects of a new ‘creative class’ [2] capable of generating a better society. The basic assumption is that the family is a purely cultural construction, an artefact. Hence, family relationships can be configured and experienced at will, with the inevitable ‘death of the family’ through the unbound morphogenesis of its natural and traditional forms [3]. From the sociological point of view, a new popular culture can become a sustainable resource for the renewal of family life as long as it is possible to trace phenomena that contrast the tendency to spread the aforementioned trickle-down effect of individualistic culture.

Specifically, new social movements and popular strata should emerge that promote lifestyles in which the family, supported by subsidiary social institutions, is considered a relational good characterized by relationships of donation, reciprocity, marital sexuality and generativity. This is a big challenge. The challenge is to show that social phenomena which (re)generate the family as a relational good exist and can spread. The hypothesis is that the birth of social movements capable of affirming a culture of family relations that can go beyond the fragmented, individualistic and emptied relationships produced by the processes of modernization is possible. In my view, the practicability of the discourse on ‘human rights’ and the ‘rights of the family’ depends on the emergence of what I am going to depict as a new ‘relational culture’ of the family [4].

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

Nowadays there is a great debate surrounding the family and what qualifies it as such: ‘what is’ and ‘what makes the family’. If it seems widely recognized that the family is a common good, on the other hand everyone interprets the family and the common good in his/her own way. It is in no way clear how the different types of family represent a common good for their own members or the community. The main finding of national and international surveys is that the family is a common good insofar as it ranks top as a place of affection, love and solidarity between people who are close. In this sense, whatever form it may take, the family is a common good simply because the majority of the population shares attachment to something which is felt to be a primary support in everyday life, a source of deep feelings and a ‘private’ space.

Only a small minority believe that the family has specific social functions for the community, namely, that it is relevant not only because of the benefits enjoyed by individuals in the private sphere, but also because of its contribution to society, in terms of demographic regeneration, the economy and the welfare of the population. The European Union definition of family concerns the private sphere alone [5], considering it a private aggregate in which at least one adult individual takes care of another individual. Although other countries have not come to legally define the family in this way, this is nevertheless the concept of family used in public policy practice. So, the question is: does the common good that the family represents only consist of a shared value that each individual experiences and interprets privately or is it something different and more than that?

The purpose of this contribution is to support the thesis that the family is a common good not of an aggregative type but of a relational type. The former is understood as a ‘total’ good (or general interest) as it consists of the sum of the well-being of individuals belonging to a group, which is sought for the benefit of each individual as such. The latter is a common good in the sense that it consists in the sharing of specific relationships from which both individual goods and those of the family community as a whole derive. This distinction is crucial to understanding how the family is not a simple aggregation of individual utilities, but a social form that generates and regenerates social solidarity and inclusion. To clarify this distinction, it is necessary to further thematize the relational nature of the family [6].

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

The core of my argumentation is that it is necessary ‘to think relationally’ about the family. Since human social reality, and the family in the first place, is made up of relations, it is only with relational thinking that one can see something which otherwise remains hidden, unsaid, indescribable and lacking reflexivity. I am referring to those relational goods on which the human quality and spirituality of every individual’s life depend [7]. The family is the first, original and paradigmatic of all relational goods. Looking at the image of a mother (or father) with a small child in her (or his) arms, you see two people and their gaze. Inside yourself, you can identify with the feelings of the mother (or father) and appreciate the gaze and gestures of the child.

The feelings and thoughts of the external observer, as well as those of the mother (or father) and the child, apparently seem to be events pertaining to their individual interior life alone. But that is not exactly how it is. What happens inside each person is the effect of being in a certain relationship within a specific relational context. The observing person is not only stimulated by the parentchild relationship she observes, but experiences that relationship in herself, in a silent dialogue with that relationship, since the parent and the child speak to her through their relationships. These are the relations which I am talking about. People look at individuals, observe their gestures and imagine their feelings, but, in reality, the sense of what happens emerges through, with and in the relations between the observed individuals and between them and the observer. We are sensitive to other people not so much because of their words, but because their words talk to us through, with and in the relationship, they have with each other and with us.

The human person is an ‘individual-in-relation’ with others in a relational context. Relations shape the social context and have an influence on the person to the point that we can say that she is ‘relationally constituted’. Let us look at a scene where a parent interacts with her (or his) child. We see two individuals and their physical actions, but we think through and with their relationship, and we put ourselves in their relationship. What we feel depends on the relationship we establish towards these figures and the situation in its complex meaning. The meaning of the situation is a relationship, or rather, a network of relationships.

The same thing occurs when observing a pair of lovers. We see two people who look at each other, talk, exchange affectionate gestures and behave towards each other in a certain way: that of a sui generis relationship.

We think that their faces, their gestures and their communicative expressions build their relationship of love, whereas it is rather that their ways of communicating are such because a specific bond of mutual love already exists between them. We wonder what the reality of that relationship is, but it remains invisible. The people living (in) this reality rarely have a reflexive awareness of it. People only realize the invisible reality of relationships when they become a problem. To make this reality emerge and be able to treat it in a counselling setting, a type of relational thinking is needed that is capable of comprehending the specific (sui generis) relationship in question and its ups and downs. It is the relationship that guides the perceptions and gives a form to our feelings. A mother with her daughter, a father with his son, a pair of lovers or a family group find their identity in the relationship of reciprocal belonging. Their feelings come from that relationship. Were the relationship different, the feelings would be different.

Emotions and feelings give people a positive identity if they generate a mature relationship [8], that is, if they foster the relational soft skills of their identities. For example, when we describe ‘a good mother’, ‘a good father’, ‘a harmonious couple’, ‘a beautiful family’, or ‘a depressed mother’, ‘an absent father’, ‘an entangled couple’, ‘an unhappy family’, etc., we refer to individual or collective qualities that are, in fact, relational goods or evils, which nevertheless remain impalpable. The problem of relational goods and evils is that they are invisible, immaterial, intangible entities. To understand what this means, we can compare the reality of social relations with that of light and air, which are also invisible entities. Indeed, we do not see light in itself, but we see things through, with and in the light. If we are in the dark, we cannot see anything, and we grope around without knowing where we are going. When the room is lit up, what we see depends on the intensity and color of the light. But we still cannot see light as such.

The same goes for relationships. We do not see light in the same way as we do not see social relationships, but it is relationships that make us see people and things. How we see others and the world depends on their intensity and color. Air is invisible, intangible too. In the same way as we cannot live without air, we cannot live without relationships with other people either. Human relationships are the air of our spirit. Without social relations, we die as human beings. The fact is that we can only perceive their existence when they are negative, cause us troubles or are not there when we need them. In the case of air this is very clear. If the air is very polluted, or too hot or too cold, then we perceive that it exists because it creates problems. The same happens for relationships in the family. It is when bad relationships appear that we perceive the existence of an intangible and vexatious reality that eludes us.

Relationships are not only part of our corporeal existence, but also and above all they are part of our psychological, cultural and spiritual existence. When they become an irritating problem, then we are forced to reflect on what to do, and we must find an ‘order from noise’. If the difficulties become very severe, we find ourselves acting on the ‘edge of chaos’. The difference between the air and social relationships is very revealing. Air is a mixture of various gases which does not have its own molecule. Social relationships are different because, when stabilized, they have a specific ‘social molecule’ [9]. To say that family social relations have their own proper social molecule, while air does not, can be explained with the following argument: while the air is only a mixture of elements, namely an aggregative phenomenon, family relations are an emerging phenomenon, which means that, whatever their form, they take on a structure having sui generis properties, qualities and causal powers which are not the sum of those pertaining to its components (like in the formation of water – H2O – from hydrogen and oxygen).

The family is not a generic primary group, but a very special type of primary group [10]. People experience the existence of real connecting structures which deeply affect their life course even when they have been broken or removed. The reason lies in the fact that like all emerging phenomena, family relationships have an autonomous existence with respect to the subjects-in-relation (in Latin to say that a certain entity ‘exists’ (from Latin ex-sister) is to say that it ‘stands outside’ what generates it, as it is a thing unto itself). To put it another way, the family has its own ‘molecular structure’ as it is a ‘relational complex’ that emerges from the intertwining between the couple and the generative relationships. This conjunction is the structural link that transforms individuals into family subjects. Therefore, what makes the social molecule of the family distinct from other social forms is precisely the fact that the conjunction between the two vertical and horizontal axes is able to give birth to a reality of a different order from the simple aggregation or coexistence of individuals who are interested in forming this bond and living in, with and through it.

By pure analogy with the biological genome, I call it the ‘social genome of the family’, as I will explain later on. It is against the backdrop of this relational structure, which is of course highly dynamic, that the family can generate relational goods (or, should it fail, relational evils) for itself and the surrounding community. The relational goods are positive externalities that have multiple dimensions, not only economic (as economists underline), but also and above all in terms of social, psychological and cultural aids for others, since the family is not only a consumer, but also a producer of many goods. Conversely, relational evils are negative externalities that involve problems and costs of various kinds for others. We live in the social world of relationships in the same way as we breathe air in the physical world, that is, spontaneously, without thinking about it, given that in ordinary life we take air for granted just as we do social relationships.

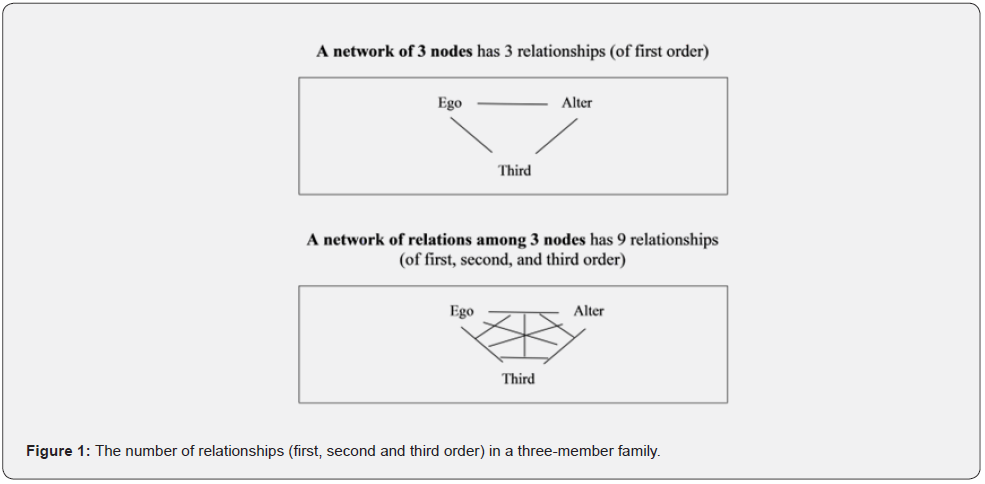

Counselling and therapy are activities that try to bring these relationships to the surface, rendering them more conscious and reflexive. In order to understand the relational dynamics in a family, practitioners need to organize their observations in a certain way, that is, they have to ponder relationships by relying upon nth-order observations and the relational feedbacks involved in them [11]. Apparently, a family of three (e.g., two parents and a child) only has three relationships (the one-to-one relationships between the three members). But, in reality, it has nine relationships, relevant to the effects of the family structure, if we consider second order (relationships between one member and the relationship between the other two) and third-order relationships (relations between first-order relations). The number of relations grows exponentially as the number of nodes gets bigger. For example, a four-member family has 126 relationships if we consider all first-, second- and third-order relationships! [12] as shown in (Figure 1). The proper functioning of the family depends on the proper functioning of all these relationships. The mystery of marriage and the family lies in the meaning of this complex relationality.

A distinction needs to be made between relational and automatic feedback. Automatic feedback can be useful in terms of producing practical therapeutic effects, for example, when the practitioner uses the technique of enjoining a paradoxical prescriptive norm that automatically changes family relationships according to the so-called Milan school model [13]. Prescribing a rule to be followed slavishly, even if you do not understand the reason for adopting it, can change the family relationship for the better but it remains a mechanical fact. In this case, social relations are not properly ‘seen’ and accounted for, they are only ‘performed’ and used without achieving a rational understanding of their meaning. If people want to have a family that is aware of what is happening within it, they have to activate a specific relationality that should be reflexive about their own relations, which means fostering a relational reflexivity in the interactions between the family members.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

We need to make two basic and parallel distinctions. The first concerns the difference between personal and social identity: personal identity is the answer to the question: ‘who am I for myself?’, while social identity is the answer to the question ‘who am I for others?’ The former is a relationship with oneself, the latter with others. The second distinction concerns personal and relational reflexivity. Personal reflexivity can be defined as “the regular exercise of the mental ability, shared by all (normal) people, to consider themselves in relation to their (social) contexts and vice versa” (Archer’s definition) [14], while, in my opinion, relational reflexivity is different, and can be defined as the regular exercise of the mental ability, shared by all (normal) people, to evaluate their relationship(s) with relevant others (in our case, primarily, the family members) and the influence of such relationships on themselves and relevant others.

Evaluation depends on the subjects and obviously has many expressive, cognitive and symbolic dimensions [15]. Relational reflexivity is needed to manage the relations between the two personal and social identities, just as it is necessary to manage the relational goods and evils of the family as a group. Why are these distinctions important? Their relevance lies in the fact that, if family members want to enjoy their living together as a relational good, and avoid relational evils, they must exercise not only their individual inner reflexivity, which gives personal identity, but essentially their relational reflexivity, which confers social identity. Personal reflexivity consists of a conversation conducted by Ego within itself taking into account the context and reacting to it in the first person, while relational reflexivity implies acting in second person, and also third person, to take care of the qualities and causal properties of the mutual relationship with Alter. Acting in the second person means that Ego treats Alter as a You who is a true Alter, not as an image of himself (or a thing, and it).

Ego acts in such a way as to create a relationship that takes into account how Alter sees him, that is, Ego modifies his own ultimate concerns by accommodating the expectations of Alter in them. The third-person perspective is also involved in the relationship, because in acting towards one another, we use images that refer to the generalized Other of the cultural context in which the interactions take place. For the family to emerge as a social subject, it is necessary that Ego and Alter take into account the social context not only as an object of their personal reflexivity, but as a reality that exercises a causal power over them due to the reflexive effects inherent in the dynamics of their relational network as such. This is crucial for the creation of relational goods, in which Ego and Alter must relate to each other by taking care of the effects of the relationship itself, and not thinking that the effects of the relationship derive directly from their individual intentions or desires for the Other. As a result, it can be said that relational goods emerge from three orders of reflexivity, i.e., in the first, second and third person.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

In pre-modern societies and again in early modernity, the world of social relationships was taken for granted. Society had a sufficiently stable reproductive character, based on mainly religious customs and habits. The globalized society in which we live today is instead increasingly morphogenetic, which means that it continuously generates new social forms. Living in social morphogenesis means having to deal with the imperative of knowing how to see and manage ever-changing relationships. If we want to orient ourselves in the world, we must necessarily make our relationships more explicit and reflexive. We cannot take them for granted. The family must respond to the imperative of becoming a reflexive we-relationship, that is, a group that is capable of acting as a relational subject in itself.

A family is reflexive not only because its members are individually reflexive, insofar as they have an inner dialogue, but because they reflect together on the common relationship that binds them as a community, however plural. Their relational reflexivity can be seen in their efforts to engage in constructive communication and willingness to find consensus on issues that are important to them. Compared to other forms of reflexivity, such as seeking individual gain in a given situation or simply adapting to the behaviour of others, relational reflexivity is a form of reflexivity that takes into account the meta consequences of a person’s actions and their reflections on other people (metareflexivity). It is the complex but everyday evaluative activity of a person who is aware that she needs to invest in her relationships in order to continue to benefit from their positive effects.

Relational reflexivity encourages a person to redirect her focus from her own immediate concerns to instead take into account the concerns of others and in this way care for the relationship. This is relational reflexivity, which is different from individual (inner) reflexivity, because it is a matter of acting in the first and second person at the same time. Family relationships change constantly, and, because of this, our comprehension needs to be made ‘more relational’. There are no longer fixed models or, as a consequence, ‘deviations’ from them: rather there are processes of relational morphogenesis in which the norm and deviance mix, making them more difficult to distinguish from each other and modifying the moral order of society beyond modernity [16].

Since, nowadays, social relationships are becoming morphogenetic, we have to arm ourselves with a new relational paradigm of the human person, the family and the whole of society. This relational paradigm is described in two volumes: for a sociological perspective [17]. Such a paradigm is needed in all human and social sciences (psychology, sociology, pedagogy, cultural anthropology, economy, etc.). But we must be careful: there are many, different so-called ‘relational paradigms’. I suggest drawing a fundamental distinction between constructivist (relativist) and critical realist (non-relativist) paradigms. On the difference between my relational sociology and relationalist sociologies [18]. I will try to briefly explain this fundamental difference in order to understand the family as a relational good and not as a mere processual and fluid event, as the relational constructivists say.

(a) In those relational approaches that adopt a radical constructivist perspective, family relationships are seen as simple transactions, processes and flows. All of their elements, namely situational objectives, means, rules and value models, are subject to pure contingency. This way of understanding family relationships is well exemplified by Giddens’ ‘pure relationship’ theory [19]. According to this author, the prevailing family pattern of the future will be the couple whose partners stay together for mere individual pleasure and convenience as long as it satisfies them, after which the relationship can disappear to give way to other relationships, as if nothing had happened. Apart from the fact that this idea of the pure relationship ignores and removes the problem of children, it is unrealistic to think that a deeply intimate relationship can disappear without leaving an indelible trace on the partners.

Human existence is always profoundly marked by this experience, as evidenced by the ordeals of divided and conflicting couples. As today’s sciences have made clear, two entities that have been in interaction for a long time, even when they separate, continue to affect each other even if they are distant and separate, living with other people (it is the phenomenon of quantum entanglement). In essence, the hedonistic and utilitarian conception of the so-called ‘pure relationship’ offers us a completely misleading and false view of the couple relationship. Behind the illusion of the pure relationship is the idea that relationships are reducible to simple communications, and communications only [20].

In brief: relations are seen as flows or transactions without specific qualities or causal powers per se because, according to the constructivist view, they lack a structure, or, better said, because their structure is formed by individuals’ subjective preferences [21]. This is a clear conflation between agency and social structures. The idea is supported by those cultural movements (including many academic scholars and even many magistrates in courts) which claim that people, as pure individuals, have the right to define family identities and family relations as they like. The prospect is as follows (I quote): “the distinction between family structures and family consciousness is no longer productive. What individualization of the family essentially means is that the perceived family is the family structure, and that consequently both the perception and the structure vary individually between members both within and between “families […] culture becomes an experiment whose aim is to discover how we can live together as equal but different […] the aim of legislation is less and less to prescribe a certain way of living, more and more to clear the institutional conditions for a multiplicity of lifestyles to be recognized […] this means that any collectively shared definition of relationships and individual positions is gone” [21]. Consequently, relational goods and evils can neither be seen nor thematized, because they cannot be explained in terms of individual tastes and preferences, but instead consist of relationships produced by couples and family networks beyond individual communications and intentions. Since reality is considered a pure social and cultural construction, the good and bad of relationships become subjective feelings. Relational goods and evils become mixed up and can no longer be distinguished from each other. Left to this view, the family becomes ‘a normal chaos of love’.

(b) Properly relational approaches differ from relationist ones because they adopt a critical realist perspective according to which relationships create structures, willy-nilly, which are networks giving rise to relational goods or relational evils. Even a family that lives in the so-called ‘chaos of love’ has a social structure, like it or not. It is not a purely processual or evenemential reality. These networks are not only made up of communications and transactions, but also of much more substantial ‘stuff’. This social fabric, like the one made up of relations of serious life (the Durkheimian “relations de la vie serieuse”), is a very complex reality that decides human destiny. It emerges from the intertwining of psychological-symbolic references (refero) and binding ties (religo) that leave a trace over time, thus forming the identity of the person throughout her life cycle. On the structure of relationships as an emerging effect of a generative combination of refero and religo [22]. In the family, communications depend on the network of relationships in which they occur, i.e., the network of concrete bonds which is family life.

For example, when a family has to make an important decision (e.g., to relocate, change a partner’s professional job, or simply where to go on holiday), each member is likely to have different preferences from the others. They perceive the decision to agree upon as a stake that goes beyond individual preferences. The decision that must be taken is a relational problem, the solution of which depends on the ability of the family network to transform individual decisions into an emergent effect that unites all the participants. The family can regenerate itself in a virtuous way if the preferences of each individual are reshaped on the basis of relationships of trust, cooperation and reciprocity with the other members. If this does not happen, relational evils are generated, and the family is at risk.

Just as a virus cannot be seen with the naked eye, and therefore we have to use an electron microscope, to see relationships we need the microscope of a relational gaze [23]. Family relationships are not just the simple exchange of communications, just as the water molecule is not a simple transaction between elements of hydrogen and oxygen. They are an emergent effect that creates another order of reality, a new substance, with different qualities and properties. Most couples today lack this awareness. Often even the educational programs that prepare young people for married life aim to guide each partner in perfecting their own practical and moral capacities to carry out their individual roles well, instead of making them relational. This leads to relational evils. To activate relational goods, both partners should exercise their reflexivity towards their relationship and continually redefine their individual and social identity, which changes over time, according to it.

Postmodern society does not help. It sees the couple as a soap bubble, like in the paintings by Hieronymus Bosch. Therefore, an increasing number of couples are prey to impeded or fractured forms of reflexivity. The partners are not able to integrate their personal and relational identity either in themselves or towards the other. The task of ‘making a family’ becomes the task of knowing how to build a We-relationship. But who is this We? And how do you build a We-relationship as a family? Here we come to the family as a ‘relational subject’ [24] emerging from a process of social morphogenesis which is the result of its members’ reflexivity.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

The process of morphogenesis, that is, the generation of new family forms, is a process that develops from an initial conditioning structure, passes through the interactions between the agents that modify this structure, and brings out a new relational structure. It is a process that takes place over time in the form of a continuous succession of cycles T1-T4 (as set out in (Figure 2)), which, step by step, generate new types of families. This schema is important because it offers a series of indications. First, it tells us that, at an initial time T1, individuals live in family structures that respond to the conditioning of a given socio-cultural system. The given family structures obviously vary according to the members’ social status, their culture of belonging, the phase of their life course, and so on. However, despite the social system’s strong influence on the individuals’ actions, in the interactional phase T2-T3, they interpret existing cultural models and react to them with their subjectivity.

Secondly, (Figure 2) highlights that new family forms do not only emerge from the will of individuals or structural determinism, but above all from the dynamics of the social networks through which people carry out their lives. In these networks, individuals react to conditioning structures in different ‘reflexive’ ways [25]. These reflexive modes can be autonomous or dependent on other people and circumstances, coherent or fragmented, or even blocked. This is where the agents’ meaningful lifestyles become important. More often than not, the relationships that mediate people’s actions towards the conditioning structures are problematic, with different, rational or emotional motivations, based on the opportunities offered by the social context. Individuals play with structures, acting tactically or strategically to achieve what they think will be their own well-being. They do not make individual decisions in a vacuum (as the economic theory of rational choice maintains), but embedded in the context of the relationships that give them identity and belonging. In short, individuals play with the interpersonal and social relationships they have, as well as those they deem possible or desirable. We can distinguish various types of morphogenesis based on the ways in which individuals interact with each other and thus shape their family in the context of their wider relationships.

a) Morphogenesis can be adaptive and pragmatic: In this case, people’s interactions do not substantially modify the original family structure, but simply adapt it to new conditions. The prevalent type of reflexivity is ‘communicative’ (i.e. dependent on significant others according to Archer’s classification) and follows patterns of habitus. People do not turn away from the internalized patterns they cling to; they seek only contingent adjustments to resolve tensions and conflicts in search of a more fulfilling lifestyle. Even when people get divorced and remarry, most mixed families come close to this type, because the second marriage does not deviate from the internalized family model. When people marry multiple times or live with different partners over and over again, without a minimum of stability, they show that their reflexivity is weak, and it can easily become a fractured or impeded reflexivity which, sooner or later, leads to the next type of morphogenesis.

b) Unstable and chaotic morphogenesis characterizes people who, by choice or by conditioning, experience interpersonal relationships as flows and processes without a relational structure that has its own normativity. In this case, they are unable to find their identity in a specific family model, and consequently adopt precarious, substantially fragile and vulnerable lifestyles. Their reflexivity is constantly fractured (they often change their minds and partners) or blocked and impeded (when they do not know exactly what they want, and, for example, chronically delay getting married, rather than firmly resolving to reject it).

c) Steered morphogenesis characterizes people who try to guide the change process with a meaningful family project in mind beyond existing models. They generate new forms of family networks that are distinguished by the fact of developing the cultural potential of the natural social genome of the family. To follow this path, a meta-reflexive mode of interaction is necessary, which is the ability to reformulate the relationship of common life beyond contingent difficulties, so as to make gradual changes to oneself and to relationships with others to repair errors and disappointments. Relational meta-reflexivity is at the basis of the day-to-day coexistence of the most cohesive and prosocial families [26].

What about current and future trends? At present, from a statistical point of view, the first two types of morphogenesis are definitely the most common in modernized countries. The idea of the family is not destroyed, but broken down, dismantled piece by piece like Lego and reassembled according to the strategies in vogue at a certain moment. Family relationship games are becoming increasingly virtual. ‘The family’ ends up being an empty noun. We can say that it exists in name only, and that all we have are names (this explains the success of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, according to which reality evaporates into nominalism; we could say: ‘stat familia pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus’, that is, the original family is just a name, we have only names).

On the empirical level, this means the predominance of morphogenetic cycles that produce families’ continuous fragmentation, which increasingly weakens people’s abilities to build stable family forms. From a relational point of view this means disaffection with marriage, an increase in single people, new games of breaking up and recomposing the couple, and growing difficulties in having and educating children. However, just when we have hit rock bottom, a process of rethinking begins. How to generate new civil norms, first moral and then juridical, relating to the right to family relationships that make people’s humanity flourish, rather than alienating them in fragmentation and social anomie? It can be hoped that the processes of morphogenesis pave the way for the creation of ‘civil constitutions’ [27] which recognize human and family rights as anthropological rights, beyond the political, economic and social rights already recognized by modernity. To give an example of human rights of an anthropological nature, let us think of the child’s right to grow up in a family and not on the street or in an institution. It is the right to a specific relationship, not a civil, political or socioeconomic right. Let’s try to understand what it means.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

The thesis I propose for discussion is that the growing processes of hybridization of family relationships will lead to new distinctions about what is and is not properly human in family relationships. These distinctions could foster a new feeling about the family, highlighting its communitarian character as a way of humanizing itself and society. What does the expression “family as a way of humanization” mean? To understand this concept, as a sociologist, I suggest that the criteria to distinguish between the humanizing (or, conversely, non-humanizing) characteristics of a family form be drawn from the assessment of the relational effects produced by the new family genome that has been created. Let us think of families created by a technological intervention (such as surrogacy) or by a legislative intervention (such as a law which legitimizes the creation of fatherless families).

What I am proposing is a reading of these phenomena that leads to relational bioethics (not relationalist, that is, nonrelativistic), according to which the humanization of a family form is evaluated on the basis of the qualities and causal properties of its relational structure. This does not mean adhering to a consequentialist ethics but adopting an evangelical perspective: ‘Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves. You will know them by their fruits. Are grapes gathered from thorns, or figs from thistles? In the same way, every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Thus, you will know them by their fruits.’ (Matthew 7:15-20, and also Luke 6: 43-45).

I will cite two examples: first, the use of reproductive technologies; second, the legislation that institutionally provides for the procreation of fatherless children. The first example is that of a Nebraska woman, Cecile (61), who wanted to ‘give’ a child to her gay son. The woman gave birth to a baby girl (Uma Louise) who was conceived with the sperm of her son (Matthew) and the egg of his partner’s (Elliot) sister (Lea). Now, Cecile is at the same time the mother and grandmother of a little girl who is at the same time the daughter and sister of Matthew. The ‘extended’ family that is therefore created is made up as follows: the grandmother (Cecile) is the mother of a daughter (Uma Louise) whom she gives to her son (Matthew) who is both the brother and the father of the child, whose mother is the child’s aunt (Lea), who is the sister of Matthew’s partner, Elliot.

This is certainly an extreme example. However, it reveals the relational games that will be possible in the future with the use of heterologous reproduction, surrogacy and other techniques that are looming on the horizon. The second example refers to a law, recently approved in France (June 2021), which extends the right to MAP (medically assisted procreation) to single women, gay, lesbian and so-called ‘asexual’ couples. Asexual couples and families are defined by the fact that they lack sexual attraction, and therefore can only have children without naturally generating them: Megan Carroll, Asexuality and Its Implications for LGBTQParent Families [28]. Until now, in France, MAP was only available to sterile heterosexual couples of childbearing age. Under the new law, women will be able to give birth to children without the help of men, and for this reason there has been talk of the ‘end of patriarchy’, ‘planned orphans’, ‘war on nature’, ‘relativism undermining an entire civilization’. In our language, institutionally approving the absence of a father in the generation of children will change family networks in a direction with unfathomable consequences.

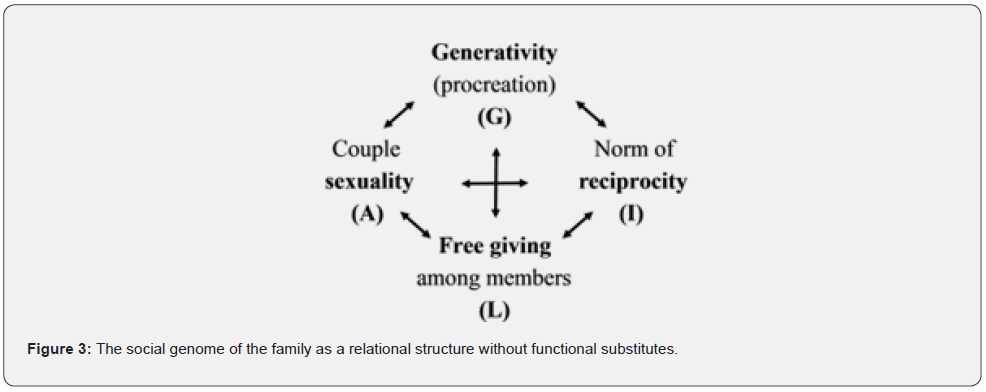

In all these cases, the hybridization of the family through the use of technologies and/or laws can be understood as a modification of what I call the ‘social genome’ of the family. This genome is neither biological nor a purely natural fact: it is the device that makes the family the necessary moment of transition from pure nature to culture (i.e., social practices) in the process of civilization [29]. If the culture we live in today is recognized as increasingly violent and dehumanizing, this is due to the systemic modification of the social genome of the family, ushering in a culture in which the human becomes an indeterminate notion and loses its proper meaning. The time has come to clarify the issue of the social genome of the family. In previous works, I proposed conceiving of the family genome as a relational structure consisting of four fundamental interconnected elements (Figure 3). The conceptualization of this structure corresponds to the relational (non-Parsonian) version of AGIL: cf. [30] These elements are: mutual free giving (L) among the members as the fundamental value that inspires life in common; the norm of reciprocity (I) as the basic rule for internal exchanges; and couple sexuality (A) as a means of cohesion and realization of the intentional generativity of the couple (G).

These elements are organized along two interconnected axes: the horizontal axis of the couple (linked by reciprocity and sexuality: I-A) and the vertical axis of parenthood (which connects free giving to generativity: L-G). The two axes, working together in a circumflex dynamic structure, generate the family and make it grow. Although here it is simplified, this way of depicting the circumflex relational structure of the family is certainly complex and challenging. It highlights how problematic it is to create a solid and stable family lifestyle based on free giving, reciprocity, couple sexuality and generativity. Indeed, families are always in transition towards an ideal, which, however, continually shifts and escapes them. In past societies, the four elements were held together by a community tradition with a religious background. In modernized countries, this is disappearing and the idea of (re) building communities which are strongly integrated by a religious sense is an aspiration that has not much chance of success.

Secularization makes the four elements more and more contingent by untying them and allowing them to combine with each other in ‘other’ ways. For postmodern culture, free giving is wholly improbable, and most often poisoned; reciprocity is replaced by the Ego’s expectation that the other members of the family will meet its needs, otherwise it finds a way out; couple sexuality is less and less regulated and detached from a clear gender identity; generativity responds to narcissistic reasons or is subject to cost-benefit calculations. The environment still has a decisive influence, both from the point of view of cultural fashions, and the ongoing importance of the partners’ primary networks of belonging – such as kinship and friends – whose consent is desired to cement the fact of living together. Civil or religious authorities are sought less and less to legitimize the new family. Marriage is replaced by a party that partners give at home with relatives and friends so that they can recognize them as such.

In family morphogenesis, if one element is profoundly modified, all the other elements and their relationships are also modified, which produces a mutation of the genome. The forces that are modifying the basic elements of the family genome are as follows (Figure 4): (L) the capitalist economy is attacking the culture of free giving and introducing utilitarian elements into the genome; today, these elements are mostly of a consumerist nature; (I) the world of digital communication is eliminating the norm of interpersonal reciprocity because it tends to isolate individuals and give them a virtual identity; people are virtually connected to the whole world, but they lose the sense of reciprocity with the people closest to them; (A) the sexual revolution is profoundly modifying the couple relationship by calling into question the male-female polarity and opening up to an indefinite number of gender identities (LGBTQIA and the rest of the alphabet); (G) physical generativity is being modified by new reproduction technologies (eugenic practices, artificial fertilization, surrogacy), not to mention the research to produce an artificial uterus.

In the light of (Figure 4), we can say that the family experiences a setback when its social genome is attacked, with the consequent distortion of its two main axes, namely the spousal couple relationship and the filiation relationship, and their interconnections. This happens: (i) when the couple relationship is not formed by sexual identities that belong to the malefemale polarity, but by changing and unstable gender identities, generating other types of relationships which are generally problematic in the medium-long term; and (ii) when filiation is obtained with the artificial intervention of technology and, above all, of a third party that makes the filiation of the child by one or both parents uncertain and problematic. The spread of these cases in almost all countries is leading to a ‘post-family society’, converging with what has been called the ‘post-human condition’, in which relationships between family members become intricate and fickle, putting into play the ability of people to respond to the needs of sustainable relational identities. I call this process ‘family warming’.

Family warming is at the same time the product and the producer of a growing hybridization of family relationships [31]. Family lifestyles do not develop the natural potentials of typically human qualities and properties but are hybridized owing to artificial post / trans-human elements. On social relationship hybridization processes, in particular resulting from new technologies [32]. People opt for a certain family form by playing games with the basic elements of the family genome, altering and putting them back together in various ways. (Figure 4) is intended as a guide to understand the enormous changes that will take place in the coming decades. It is a question of understanding to what extent it is possible to modify the family genome without undermining an entire civilization.

However, at the same time, we can also imagine that new ways of activating the genuine family genome are opening up through a process of cultural change that is more respectful of the inherent nature of the family. What we are observing is perhaps the advent of a new ‘axial age’ (the term is by Karl Jaspers, Max Weber and Shmuel Eisenstadt) [33], understood as a process of epochal cultural change that revolutionizes the tension between the transcendental and the mundane order. In the perspective proposed here, the crux of the matter is not preserving a fixed and immutable genome, but, on the contrary, ensuring that the family genome can actually operate in such a way as to achieve a new modality of making the transition from nature to culture that enhances, rather than alienate, the human qualities of family relationality.

The ‘normo-constituted’ family is the term I use for those families that manage to make this kind of transition from nature to culture while preserving the human qualities and properties inherent in the family’s ontological genome as a latent sui generis reality that wishes to flourish to its full potential. This idea goes hand in hand with integral ecology which today rightly claims to promote a sustainable ecosystem from both a physical and a socio-cultural point of view. We may say that we need to promote a sustainable family by making the elements of its social genome and the ways of connecting them sustainable. We need to understand if and how it is possible to regenerate the family genome under these new historical conditions.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

The Family as A Relational Good

One might wonder whether being part of the family as a We (its We-relationality) means being part of an imposed entity (a systemic, holistic, institutional order) which forces the individual to submit to others, or if it is a reality that allows a person to flourish through a certain quality of her intersubjective relationships.

Of course, we know that there are a whole host of different family situations, because these two tendencies-social control and subjective expressiveness – mix in infinite ways. However, what I want to emphasize is the possibility of distinguishing between families that produce relational evils and families that produce relational goods [34]. This distinction depends on whether or not a family is able to mature as a We in which each person can personalize her role. This means that the family is a relational good in itself, which generates innumerable other relational goods, when it becomes a mature ‘relational subject’.

The relational subject is neither the ‘plural subject’ nor the ‘we think’ to which some refer [35]. Neither is it a type of collective conscience [36]. It is awe-relationship. There is no collective conscience that thinks for each member of the family but there is undoubtedly a collective culture in the sense of a set of representations, images and lifestyles which are shared by many individuals and influence their agency. However, this is not to say that the We signifies that everyone thinks in the same way. Something similar can occur in tribal societies, where individual reflexivity is highly dependent on the clan’s socio-cultural structure. The members of the family are a We in that together they generate and enjoy a good that is born and is compatible with their differences. It means sharing a well-being that respects the freedom of each member. This ‘good’ is everything that is done together and shared in trust (eating, walking, going on holiday, having fun together, etc.) or that stimulates each member’s cooperation (in the division of labour or the decision-making process, etc.).

Relationships unite us with, and at the same time differentiate us from, others. In the family, they make us different within the We-relationship that we share. In a special way in the family, this property of social relations consists of the fact that they unite the related subjects at the same time that they promote their differentiation. I call this the ‘enigma of the relationship’ [37]. The relationship means distance, which implies difference, but at the same time it also implies a connection, link and bond. We have to understand how the good in the We-relationship can be compatible with the differences between those who generate and take advantage of it. Let us make an example. A mother and a father are truly ‘generative’ when, while aware of the fact that their offspring is a person born of them, and therefore is part of their identity (as the father and mother), they realize that she or he is not the child of two individuals, but of their relationship.

As such, the child expresses and materializes the essence of the family as a relational good. Those parents who say ‘I want a child to fulfil my desire for parenthood’ (that is, in my child I find my identity) do not generate a person other than themselves, but they generate (or try to generate) an ‘avatar’ of themselves. They generate an Other who has to realize his own Ego in an imaginary world. This kind of relationship is one that comes from an identity that seeks to direct and possess the other. The Other becomes entirely subordinate to the identity of the parent, with no real reciprocity between parent and child. The relationship becomes narcissistic, and so the only relational goods that can be generated – if any at all – are partial and insufficient.

To generate a relational good, the differences between the members of a family must be managed in a certain way, that is, treated according to the norm of reciprocity. When this happens, we perceive the idea that loving means knowing how to respect the Other as different and living this as a gift. Love is not only a subjective feeling, but it is above all a relationship of full reciprocity, and it is this relationship that gives rise to personal inner feelings. In the love relationship, difference is not a simple distance or divergence to be tolerated, but a lifelong challenge that helps bring people together, when they understand that differences add value to all the participants in the relationship [38]. The relational good lies inside the relationship, not outside it. The good is the ‘included third’ that emerges from the interactions between the subjects who live in the relationship [39].

If the relationship stops being a meaningful difference and is reified (becomes a ‘thing’), then it generally leads to the degradation of the human person. This happens to us every day, when, instead of having an ‘I-You’ relationship with another person, we label and commodify the other person in an ‘I-It’ kind of relationship [40]. The relationship with the Other becomes a cliché, a stereotype. This happens in the family when we give up trusting and collaborating with others because we consider them incapable or unreliable. In this case family relationships generate relational evils. Family life becomes a producer of relational goods if and when its members are able to manage their differences and the connected needs ‘relationally’, that is, in the knowledge that the relationship unites those who are different while maintaining and even enhancing their differences. Relational goods are resources which consist of relationships; they are not material things or functional performances. We can now understand why the family is a common good, not in a public or private sense, but in relational terms. A typology of social goods (in general) can be useful to better understand these differences from the point of view of how relationships are configured.

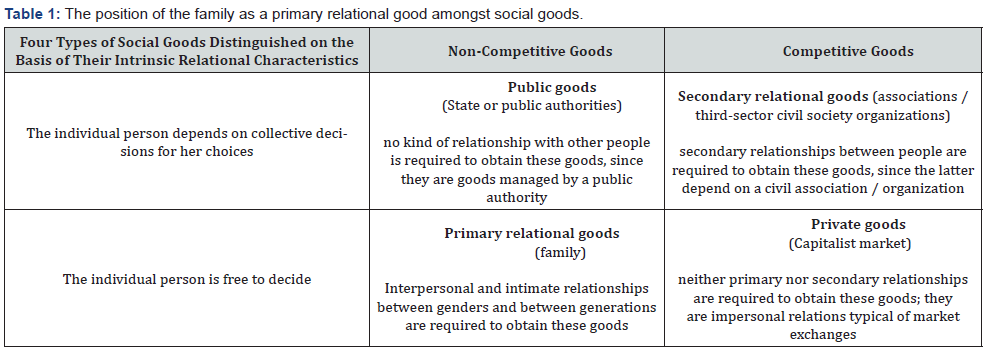

If we classify social goods according to two axes: (i) the competitive/non-competitive character of the good, and (ii) the chance to choose/not to choose the desired good, we find four types of social goods (Table 1).

Public goods are not competitive, and people cannot choose them individually. No kind of interpersonal relationship with other people is required to obtain them and they concern benefits and rights managed by a public authority (how we use the streets, public spaces, museums, etc.). Private goods, on the contrary, are competitive and can be chosen freely. Neither primary nor secondary relations are needed to acquire these goods, only impersonal relations typical of market exchanges (anyone can buy something by choosing from various distributors of goods).

Unlike these polar goods, there are two types of relational goods. The first type is competitive goods, namely secondary, associative relational goods, that do not envisage an individual choice and are obtained through secondary relationships between people who share membership in a civil society association (trade associations, trade unions, sports or cultural associations, etc.). Then, there are non-competitive goods, namely primary relational goods, which people are free to choose and are obtained through good, interpersonal and intimate relationships. One such primary relational good is the family. Precisely because the family is a non-competitive good (it is a social form without functional equivalents), in which we take part of our own free will, this social form can produce relational goods which other social forms cannot create. The family is a relational good (i) in itself for its members, given the fact that it can generate what other lifestyles cannot generate, and (ii) for society because it develops functions that no other form of life can fulfil.

Among the many considerations that could be made on (Table 1), I would like to underline those relational goods produced by the family which are the social virtues. The family is not only a place where individual virtues are cultivated but it is also and above all the non-fungible ‘social worker’ that transforms individual into social virtues. It is precisely by transforming the individual into the social that the family takes the human being’s individuality to the level of a shared collective human culture. I would like to emphasize that the concept of ‘virtue’ can and must refer not only to individual actions, but also to social relations as such. Primary social virtues, such as giving and receiving trust, cooperation, reciprocity, responsibility and solidarity, are learned within the family. Otherwise, they are learned no more. This is why we say that the family, founded on full reciprocity between genders and between generations, is not fungible, has no functional equivalents and is the greatest social (not merely private) resource that society can have. If a society wears down or even loses this resource, it will face so many difficulties, of such great entity, that it will be unable to survive in the long run.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

According to the above schema of family morphogenesis (Figure 2), there are two possible ways of guiding the processes currently regenerating the family:

a) By intervening on the networks of primary relationships (in the intermediate temporal phase T2-T3) to create families capable of organizing themselves as ‘social relational subjects’, in order to develop a new family structure that can spread in ever wider networks (this is the path generally chosen by educational programs, including family pastoral care);

b) By acting on the societal system (at time T1) that conditions interactions both between the family and society, and within the family itself, to support changes in the interactions during phase T2-T3 (this is the path of social, economic and cultural policies). These two ways must work in synergy, and both require a new culture of social relations, which I will try to set out in brief.

(a) Acting on the interactions between people who make up a family. The question here is whether to act on individuals or their relationships. Most educational activities choose the first path, that is, they try to train individuals. This path is often ineffective, however, because people depend on relationships. Only a new culture of relationships can interrupt the fragmentation of families currently underway. The family is not a common good because the members share the same ideas, as many people believe, but because they understand and respect their differences while at the same time setting most value by the good of the relationship as such. However, in the end, the path of education alone cannot produce a substantial socio-cultural change if it is not supported by a modification of the social system that conditions people’s behaviors and relationships.

(b) Acting on the societal system that conditions interactions. Operationally, this means recognizing family rights at the institutional level. In order for families to carry out their tasks and build trust and social solidarity, they must have access to rights as families, not as an aggregate of individual rights. This means recognizing the citizenship rights of the family. The family is a social subject that has its own set of rights and duties in the political and civil community due to its irreplaceable, effective mediation between individuals and the community.

Political and legal institutions can be evaluated according to the type and degree of promotional recognition given to the family as a producer of relational goods. Indeed, many politicaladministrative systems penalize rather than promote families because they do not give due recognition to the social functions performed by the family. This lack of recognition explains the decline in the birth rate and the consequent ageing of the population, the growing number of lonely elderly people, the fragmentation of families and communities, and many other social pathologies. A social policy can be deemed ‘family friendly’ if it explicitly aims to support the social functions and the added social value of the family.

These policies must not be instrumental and must be clearly distinguished from demographic policies, policies against poverty and unemployment, and other objectives which are certainly very important, but different in kind. It is necessary to combine policies on equal opportunities for women (gender mainstreaming) with adequate family mainstreaming, which consists of policies that support family relationships, that is, reciprocal relationships between genders and between generations. As examples we can cite: policies to reconcile family and work; tax policies that take into consideration the family based on the number of members and their age and health conditions; educational, social and health services concentrated upon support for couple and parental relations, etc.

Some noteworthy initiatives go in this direction. For instance:

(a) EU local family alliances [41], that is, family-friendly policies pursued together by public, private and third sector actors by building cooperation networks between them in the local community. Every local community actor (schools, companies, hospitals, shops, banks, entertainment venues, public institutions, etc.) provides its own resources and facilities to promote intraand interfamily relationships. They are coordinated to provide support to families in every sphere of daily life [42];

(b) family group conferences, that is, interactive, guided and supervised meetings, organized to involve families who share similar problems, especially having deviant or troubled children, through the mobilization of a wide network of participants, such as relatives, friends, teachers, doctors, significant others [43];

(c) ‘family districts’, i.e. a new way of mobilizing as many resources as possible in a territorial community (called a ‘district’, normally a valley) to offer services suitable for family life according to each phase of its life cycle, conceived in the Province of Trento (Northern Italy) [44]. All these initiatives are based on a relational philosophy of social work and networking methodologies to support families [45]. Their aim is to promote the family as a relational asset for the person and the community through interactive networks that stimulate the development of the family’s natural potential. They are examples of how relational steering can be the solution which transforms relational evils into relational goods.

- Review Article

- Abstract

- Premise. Counteracting The Trickledown Effect of The Chaotic Morphogenesis of The Family: Can It Be Done?

- What Does It Mean to Say That the Family Is A ‘Common Good’?

- What Does It Mean to Read the Family in A Relational Mode (i.e., ‘Relationally’)?

- The Imperative of Relational Reflexivity to Renew the Family

- We Need a Relational (But Not Relationalist) Paradigm

- Understanding Family Morphogenesis: Can It Be Steered, And, If So, how?

- The Humanizing or Non-Humanizing Characteristics of a Family Depend on Its Social Genome

- The Family as A Relational Good

- Can The Family Genome Be (Re)Generated?

- Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

- References

Summary: why the normo-constituted family is and remains the source and origin of a good society

Empirical investigations on the family, at international level, show that the normo-constituted family (i.e., families corresponding to the original social genome) is a resource of added social value, not only because it offers better opportunities to individuals in terms of well-being, but also and above all because it generates a socially inclusive community, that is, a civil and public sphere which promotes the common good. A wide panorama of national and international surveys is debated in the book [46]. It is not true, as some argue, that the family is an obstacle to the formation of social capital in society. Instead, there is a synergy between the social capital of the family and that of the surrounding community, as well as generalized social capital [47]. These results lead to a very precise conclusion: the normo-constituted natural family is and remains the vital source of society as long as a new popular culture is capable of expressing a new way of passing from nature to culture. This challenge lies in the type of culture that can master the use of new technologies in the morphogenetic processes.

It is possible that the globalization experienced from the end of the 20th century to the beginning of the 21st century will suffer repercussions, and that local popular cultures will review their relationship with nature and the environment in the light of greater sustainability. The society of the future will have a greater, not lesser need for the family, for the multiple roles it is called to play in making personal and social virtues flourish and, ultimately, in creating a better society. As in other historical periods, human progress depends on the fact that the family can be the source of those relational goods which, as an expression of mutual love between people, are capable of opposing cultural regression and any dictatorial political system. The distinction between the human and non-human characters of a family form should be drawn according to its social genome and effects.

After all, the family remains the ideal for people all over the world. The constitutive genome of the family does not cease to be the fons et origo of society. Without this genome, society loses the primary factor that humanizes people and social life and degrades into a chaotic ‘family warming’ analogous to the global warming of the physical ecosystem. The problem is how to ensure that the distorting effects of the family’s own social genome are controlled, minimized and made reversible. We can hope that, after the deinstitutionalization of the family, a new historical phase will begin in which new relational structures can emerge, giving a new, even institutional meaning to the family as they update its social genome [48].