Improving Tax Transparency with Naming and Shaming Approach: A Comparative Study and Public Opinion in Indonesia

Neni Susilawati* and Khairunnisa Nurul Nandini

Department of Fiscal Administration Science, Faculty of Administrative Sciences, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia

Submission: November 09, 2022; Published: November 18, 2022

*Corresponding author: Neni Susilawati, Department of Fiscal Administration Science, Faculty of Administrative Sciences, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia

How to cite this article: Neni S, Khairunnisa Nurul N. Improving Tax Transparency with Naming and Shaming Approach: A Comparative Study and Public Opinion in Indonesia. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2022; 19(5): 556023. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2022.19.556023.

Abstract

Tax transparency issues always arise from public opinion regarding tax compliance. There is not much empirical evidence yet regarding its effectiveness in improving tax compliance. However, practice in several countries shows that public disclosure of tax information has had a positive impact on reducing tax arrears and the level of tax non-compliance. Naming and shaming is one of the public disclosure instruments. For this reason, this study compares naming and shaming practices in several countries and explores public opinion on the naming and shaming approach. The results show that most of the respondents supported the concept of public disclosure on tax through naming and shaming to exert social control over taxpayers’ behaviours that harm state revenues.

Keywords: Naming and shaming; Public disclosure; Tax compliance; Tax transparency; Public opinion

Introduction

The issue of tax transparency is becoming increasingly prevalent as digitization advances. Prior to more than a decade ago, few professionals discussed or wrote about tax transparency. Exists transparency in the present day? The response depends on your definition of tax transparency [1]. Social information can positively influence, for example, tipping behaviour, environmentally conscious behaviour, and political participation [2]. When people are asked about the moral implications of taxes, complaints about the transparency of the allocation of tax monies invariably surface, according to the author’s survey of public opinion. People desire transparency on the state’s use of the taxes they have paid. Is tax transparency solely applicable to the government? Absolutely not. Yavaşlar emphasized that tax transparency encompasses a broader scope, including the transparency of taxpayers to tax administration, government transparency to the general public, and transparency of third parties in the tax system (tax cutters and collectors) [1].

There are three recent changes that are fundamentally altering the nature and perception of tax transparency. First, digitization that facilitates data interchange is crucial for the implementation of automatic information exchange (AEoI). With digitization, tax authorities can utilize taxpayer data for data analysis and assessment purposes. Second, the long-standing notion of tax secrecy has begun to face opposition from the public information community. In recent years, networks of investigative journalists and non-governmental organizations have demanded explanations for tax leaks and scandals, putting significant pressure on the tax administration to disclose information regarding its efficacy in combating tax evasion. Thirdly, tax authorities have discovered that public disclosure is a new instrument for tax enforcement with an emphasis on a naming and shaming approach [1].

Consequently, it is vital to discuss the advantages, disadvantages, and restrictions of expanding tax transparency. The extent of data collection and utilization must be proportional to tax administration. Likewise, the revelation of public information as a measure of tax administration and tax enforcement accountability must be debated with an open mind. Tax secrecy and the possible benefits of establishing tax transparency must be thoroughly analysed and weighed. This new paradigm must be examined since Indonesia’s tax revenue has not yet increased significantly in comparison to its potential and that of other countries.

It is ironic that Indonesia ranks third in Asia-Pacific for the lowest tax ratio despite being the fourth most populous nation. In the past decade, Indonesia’s tax ratio has never deviated from 10% to 11%. The tax ratio compares the amount of tax revenue to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [3]. In 2019, Indonesia’s tax ratio declined by 0.4% compared to the previous year, reaching 9.8%. Indonesia’s tax ratio in 2020 suffered a dramatic fall to 1.3% and achieved its lowest point in the last five years, at 8.2% [4]. In 2020, the tax ratio of other ASEAN nations, including Singapore, reaches 13 to 14%, the Philippines, 17 to 18%, and Thailand, 17 to 17.5%. Indonesia’s low tax ratio will make it harder to improve things like facilities, infrastructure, education, and other welfare-related projects [5].

This stalemate demonstrates that practically all tax reform initiatives deployed to far have failed to significantly increase tax revenues. Given that Indonesian society is highly diversified and multicultural, it is time to implement a new strategy, namely a socio-culturally oriented strategy. According to the findings of Fauzan Misra et al. [6] sociocultural variables play a crucial role in regional politics [6]. From this description, the researcher believes that sociocultural issues must also be part of the taxation process.

There is limited empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of naming and shaming in enhancing tax compliance, although implementation in various countries, including Japan, Norway, and Slovenia, has led to favourable increases in state revenues [7]. The novelty of this research rests in the absence of a specific study on the implementation of tax transparency with naming and shaming in Indonesia. As a preliminary stage, the researcher conducted a comparative analysis of naming and shaming methods in numerous countries in America and Europe and surveyed public opinion regarding the applicability of the technique in Indonesia.

Tax transparency also plays an essential role in fostering the public’s trust. The public’s trust can promote voluntary compliance, which is crucial to the success of the self-assessment system [8,9]. Some people do not comprehend the significance of paying taxes, and others are reluctant to pay taxes because there are no advantages to doing so [10]. Taxpayer trust has a strong impact on compliance [11]. A further cause is that the Directorate General of Taxes (DGT) lacks the ability to observe and follow up with taxpayers who do not pay their taxes, resulting in taxpayers failing to meet their tax responsibilities [12]. These studies demonstrate that tax transparency is an issue in Indonesia [13- 18].

One of the instruments of tax transparency is strengthening social sanctions through a naming-and-shaming approach. Essentially, the technique or strategy of “naming and shaming” is a tactic to disseminate to the public evidence of tax infractions by disclosing the identities and signs of tax noncompliance by individuals or companies. Dwenger and Treber (2018) conducted a study in Germany that explored techniques for boosting transparency and tax compliance [19]. The research conducted by Dwenger and Treber (2018) indicates that naming and shaming will considerably reduce tax debt among taxpayers. The naming and shaming method has been applied in numerous nations, including Brazil. The Brazilian Ministry of Finance has implemented the strategy since 2015 to enhance tax compliance in the country [13].

In most nations, tax transparency still lacks a precise definition. Tax transparency refers to the availability of relevant information. Additionally, tax transparency refers to the availability of all information to anyone. The two directions of tax transparency are taxpayer openness and tax administration transparency. Taxpayer transparency means that taxpayers give the tax authorities relevant information, while tax administration transparency means that taxpayers have access to all the data and information kept by the administration [1].

Transparency is directly tied to trust, which helps foster trust between taxpayers and tax administrators. According to Siahaan, the government’s transparency can give the community an accurate depiction of what is taking place within the government [14]. Naming and shaming is one of the methods of tax transparency that might encourage tax compliance by increasing social consequences. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, “naming and shaming” is the act of disclosing to the public that a person or organization has acted improperly or unlawfully.

A further definition of “naming and shaming” is the imposition of a punishment that is carried out by means of dissemination or public revelation of a business or individual that commits tax fraud [15]. These methods are both effective and economical for enhancing tax compliance [16]. The OECD (2017) says that naming and shaming is the fourth most effective way for tax enforcement [17].

Methods

Researchers investigated the “naming and shaming” approach to promote tax transparency using survey data collection techniques and literature reviews. Online questionnaires were distributed to taxpayers via multiple social media channels. During the data collection period of July to August 2021, 105 respondents from various cities in Indonesia provided information to researchers. This study used univariate quantitative analysis. This study uses a literature review to look at the use of “naming and shaming” in several American and European countries, as well as the use of “naming and shaming” to increase tax compliance, as described in books, journals, and online articles.

Result and Discussion

Naming and Shaming Practices in several American and European countries

Multiple nations have also introduced naming and shaming procedures, and the outcomes have been proven to promote tax transparency and compliance. The application has been applied in one of Europe’s developed nations, Slovenia. Slovenia adheres to three tax systems, including direct income tax, direct property tax, and indirect tax. However, according to the Slovenian tax administration, the tax debt in the country remains significant, as evidenced by the fact that the tax debt on corporate income taxes reaches 80% and the tax debt on the self-employed climbs to 7.5% to 8% [19]. Various instruments have been implemented such as reminders of tax payments every week after the payment deadline has passed, not only that, but the Slovenian tax administration also uses debt collection measures such as interest and penalties for late payments, but these are ineffective and do not bring significant results.

The tax administration in Slovenia laments the high level of tax evasion and the public’s disregard for meeting its financial commitments. In November 2012, the Slovenian government approved a law for the implementation of the “naming and shaming” policy to lower the high level of uncollectible tax debt. The initial implementation of the law occurred at the end of March 2013. Tax debtors have around four months to settle their arrears before information and data are released. In the meantime, those who have not yet settled their tax bills were named and shamed between April and March 2013 [19].

The naming and shaming law permits the tax administration to publish information about “taxpayers in arrears,” who have debts over €5,000 and have not paid for more than 90 days. On the 25th of each month, the Slovenian tax authority determines whose taxpayers are in arrears, and between the 10th and 15th of the next month, the information and statistics of these taxpayers are made public. Information and data published in the form of the taxpayer’s name, address, and identification number; additionally, for companies in arrears, information and data published in the form of the names and addresses of beneficial owners who directly or indirectly own more than 25 percent of a corporation’s share capital. The “naming and shaming” list was first posted on the website of the tax administration in April 2013. It now has the names of 4,476 businesses and 5,091 individuals. The information clearly identifies the taxpayer and is not updated every month, which means that delinquent taxpayers will have their information published for at least a month. If they have repaid their bills, taxpayers might disappear from public notice. Consequently, societal pressures and reputational issues play a significant influence in how individuals respond to naming and shaming policies [19].

Not only in Slovenia, but also in Brazil, naming and shaming was established in 2015. Brazil has one of the most extensive, intricate, and costly tax regimes. In a world where consumption, capital, income, property, and commodities are subject to taxation. National tax receipts reached 33.74 percent of GDP in 2014, with federal taxes accounting for 68.9 percent of the tax burden, followed by state taxes at 25.22 percent and local taxes at 5.82 percent [20].

However, in 2014 there was also Brazil’s tax gap which was at 23.6% of aggregate tax revenue collection, and at 8.6% of the country’s GDP. Not only is the tax gap high, the tax debt of individual and corporate taxpayers in Brazil has soared to 526 billion dollars [21]. Various steps and strategies have been implemented by the Brazilian government to reduce the tax gap and avoid tax avoidance, namely the large investment in training of tax auditors, the establishment of a tax payer unit and continuous monitoring of strategic industries [20]. However, these measures are not effective in reducing the tax gap, the Brazilian government took steps new billing the application of naming and shaming in order to build the idea of transparency of tax [21] Implementation of policies naming and shaming is done by publicizing the 500 taxpayers who have a track record of bad and disobedient of paying their tax obligations.

The information is published on the website of the Brazilian Ministry of Finance on the 10th of each month [20] and includes information on company and individual names, company registration numbers or individual identity card numbers, as well as reasons for inclusion in the list naming and shaming. This information can only be deleted if the tax debt has been paid or by court order [21]. This is different from the implementation of policies naming and shaming in Slovenia and Brazil. Policy of Naming and shaming in Ireland is applied by means of issuing a list of violators of tax on national web sites each quarter by the revenue commissioners. The list of tax violators details taxpayers who are bound by cases with tax courts over penalties, imprisonment, or other penalties. However, the list of tax violators is published only by taxpayers who have cases exceeding 1 million euros and is published by listing the name, address, occupation, penalty or fine, as well as a description of the violation violated by the taxpayer [1].

The public will respond to the revelation as information and data on taxpayers who breach the law are published. It is anticipated that taxpayers who violate this regulation will experience a deterrent effect, causing them to adjust their behaviour and become compliant taxpayers. It is also associated with societal pressure and personal reputation. According to studies by Morse [22], when reputation becomes important to individuals and groups, there is a strong likelihood that compliance will increase.

Public Opinion on the Naming and Shaming Approach

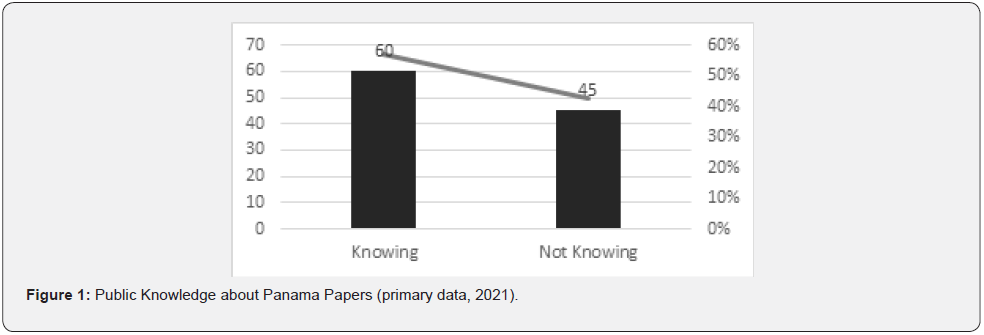

The circulation of the Panama Papers is one of the acts of naming and shaming that have occurred in Indonesia. 57% of respondents (60 individuals) claimed to be aware of the news regarding the tax debts of various Indonesian businessmen revealed in the Panama Papers. Those who are familiar with the Panama Papers believe that they contain information relating to tax avoidance, leaks of secret documents, the identities of tax evaders, and Tax Haven (Figure 1).

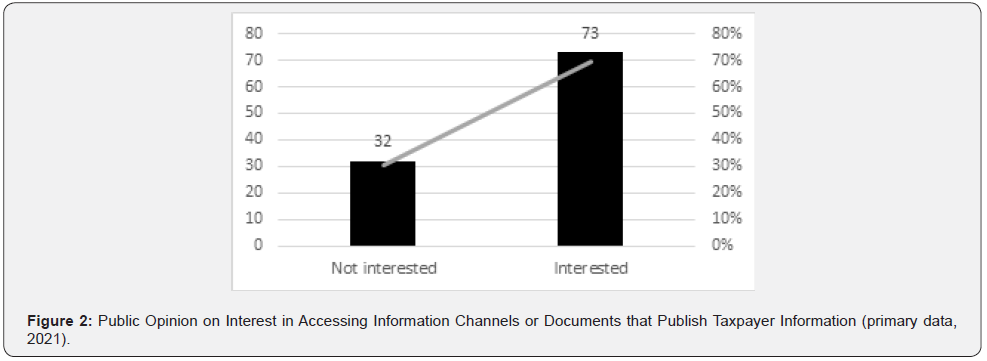

The amount of respondents who are aware of the Panama papers demonstrates the public’s interest in the publishing of tax information from other taxpayers. As with public interest in other investigative and criminal news, most respondents, 70 percent (73 individuals), are also interested in accessing information that publishes the tax information of other taxpayers (Figure 2).

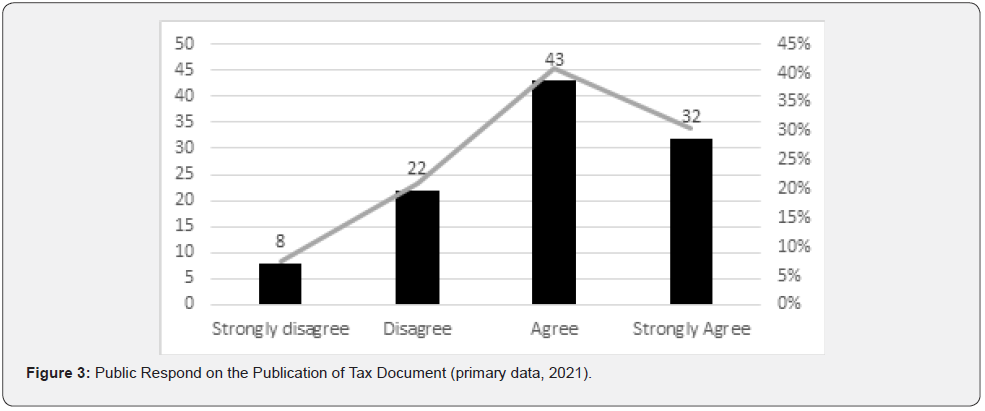

The researcher queried 105 respondents regarding their stance on the publishing of tax data such as the Panama Papers, which provided information on tax debts and tax avoidance by Indonesian taxpayers. The majority of respondents, including 41% (43 individuals), agreed with the statement, while 30% strongly agreed, 21% disagreed, and 8% severely disagreed. In other words, 71% of respondents viewed the naming and shaming technique favourably. This is intriguing empirical evidence because it suggests that the community’s social character will be able to support the practice of naming and shaming in Indonesia (Figure 3).

In a nation with a high level of social control, such as Indonesia, a supportive character such as this is essential if the naming and shaming strategy is to be implemented. Social control is the application of techniques and strategies to avoid deviant human behaviour in society. If the community has a high level of social control over noncompliance or tax avoidance, then the practice of naming and shaming will increase tax compliance in Indonesia.

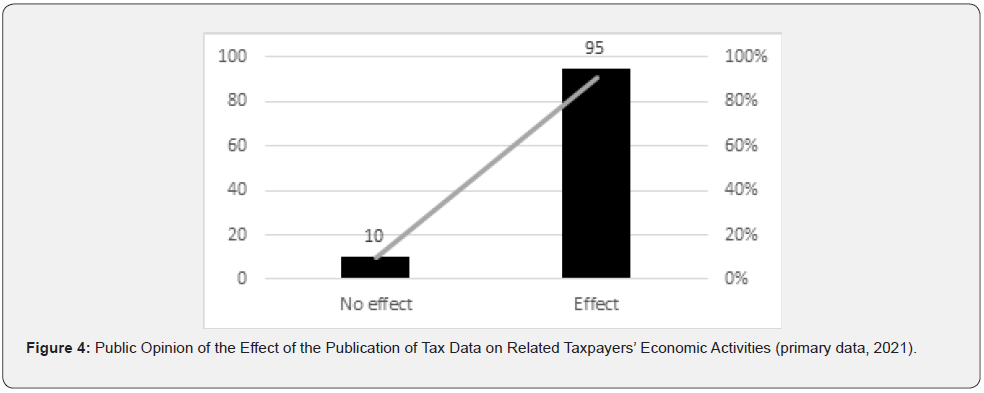

Will the release of tax information impact the economic activities of taxpayers whose information is made public? Ninety percent of respondents (95 individuals) feel there will be an effect. It is anticipated that taxpayers whose tax noncompliance is disclosed will lose their reputation and trustworthiness (Figure 4).

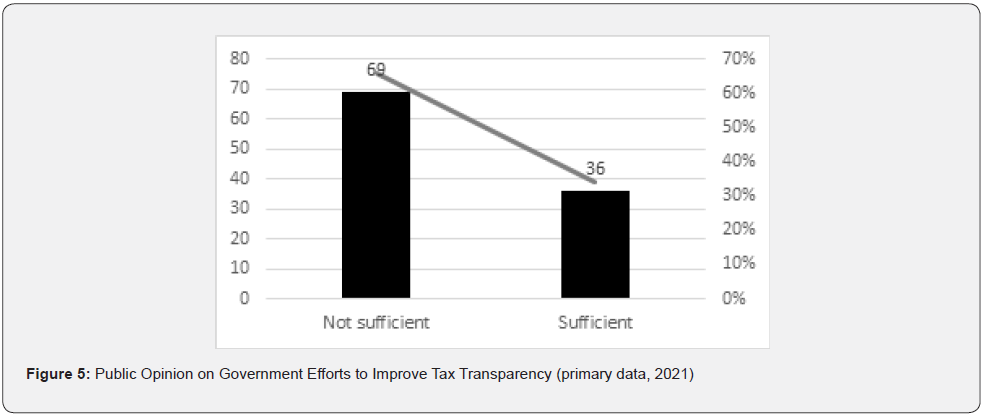

The community considers the government has not made sufficient efforts to improve tax transparency. Uneven distribution and absorption of tax information at all levels of society is one of the factors determining the level of tax literacy [9], which has repercussions for taxpayers’ reluctance to pay taxes (Figure 5).

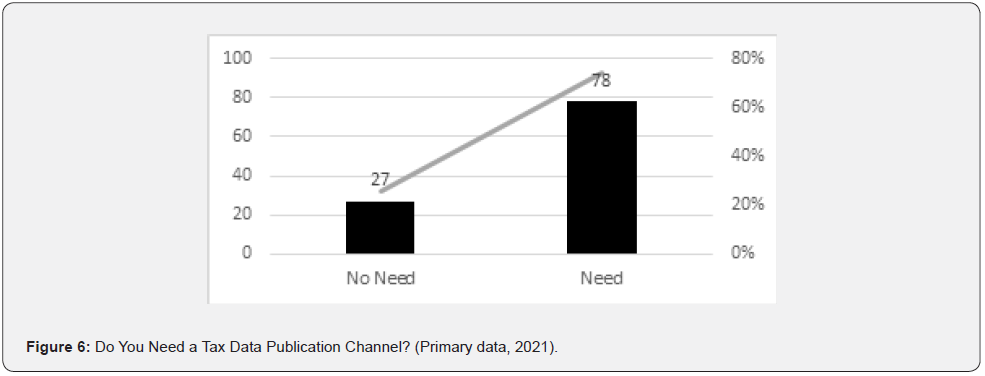

The public accepts the existence of an information channel that distributes tax data, including taxpayer noncompliance data, in order to promote tax transparency. The majority of respondents, 74% (78 individuals), said that the public required the information channel to promote tax transparency and taxpayer knowledge. A tiny percentage of respondents, up to 26%, opined that such information conduits were unnecessary due to the secret nature of taxpayer data. From this, we might conclude that the public desires publication of tax information for the purpose of bringing disobedient taxpayers to light (Figure 6).

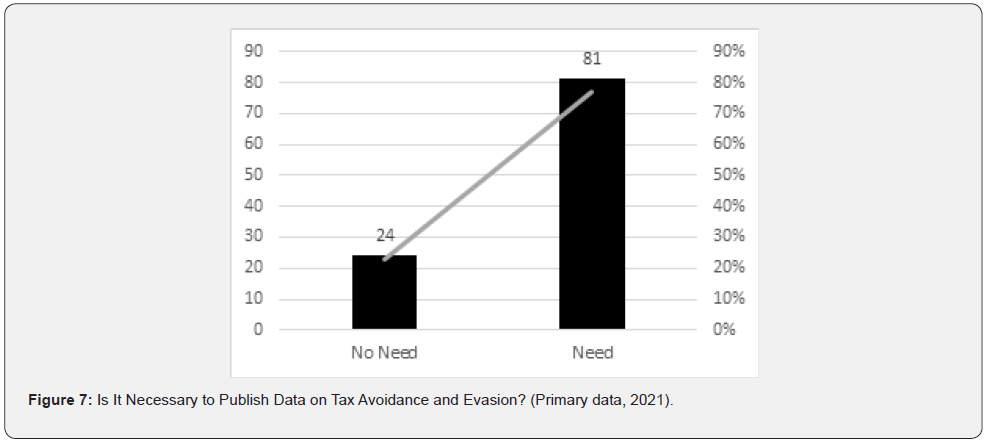

In accordance with the evaluation of the necessity for a tax data publication channel, the majority of respondents, namely 77% (81 individuals), stated that the public need information on taxpayers who engaged in tax avoidance and tax evasion. In this instance, the community’s social control in the era of digitization and social media will be able to assist the government in repressing taxpayer behaviors that affect state earnings. Moreover, 23% of respondents believe that tax avoidance data is confidential information that taxpayers and tax authorities alone should possess (Figure 7).

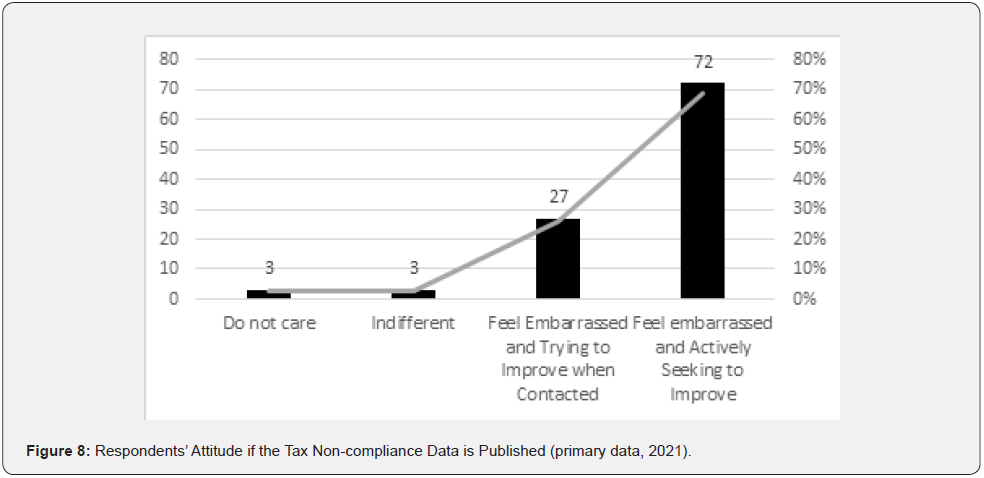

After exploring respondents’ perspectives on the disclosure of other taxpayers’ tax information, the researcher posed a question that shifted the respondents’ perspective to that of the respondents themselves. In other words, if the tax information of the respondents as taxpayers is disclosed to the public in conjunction with the disclosure of the tax information of noncompliant taxpayers, how do the respondents feel? Evidently, the results are quite favourable. Still present in the community’s personality are practices with strong social ties from the East (Figure 8).

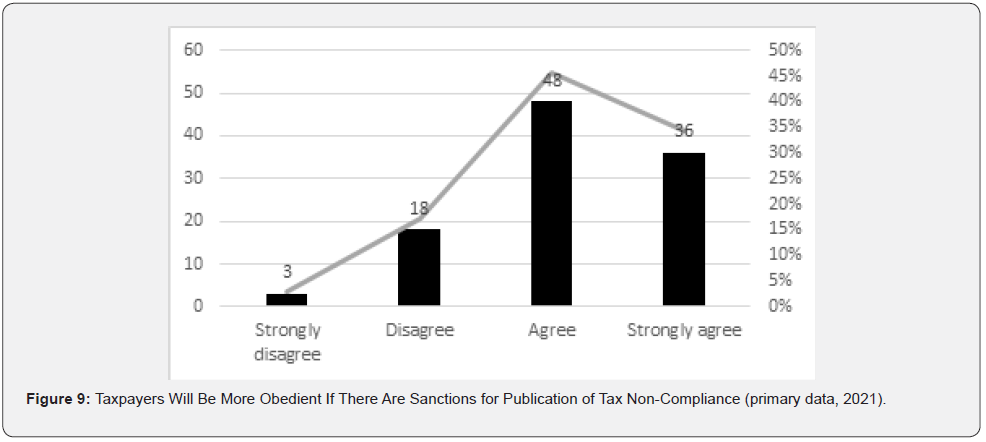

The majority of respondents (69 percent, or 72 individuals) answered that if their tax noncompliance was discovered, they would feel ashamed and work to improve their reputation. This was followed by another 26% (27 individuals) who claimed they would feel humiliated and try to improve if contacted or warned by tax authorities. While the remaining 3% of respondents claimed to be normal and the last 3% were apathetic. Obviously, this is fantastic news, since if the social control strategy of naming and shaming is used, its potential efficacy is highly promising (Figure 9).

Confirming the researcher’s hypothesis that the existence of consequences for noncompliance publications will influence taxpayers’ compliance behaviour patterns. Eighty percent of respondents provided responses that support the researcher’s hypothesis (46% agreed, 34% strongly agreed) (Figure 10).

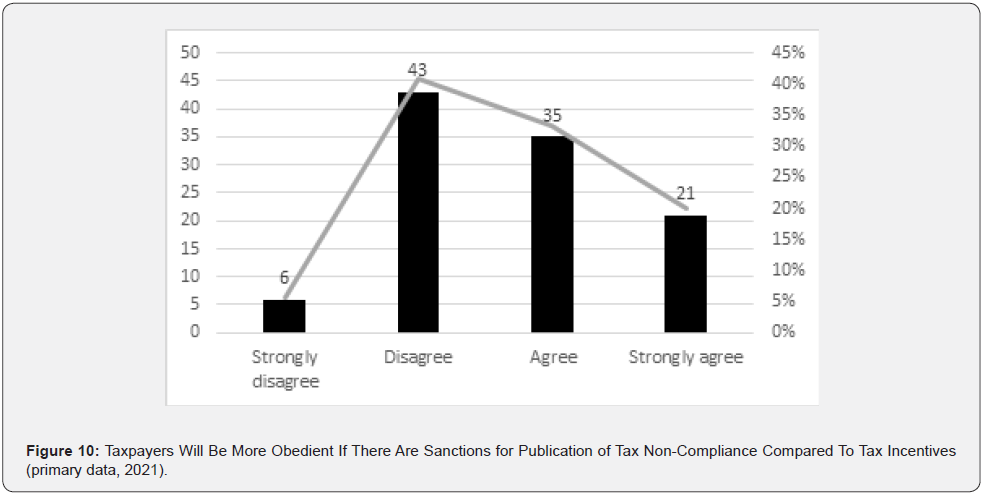

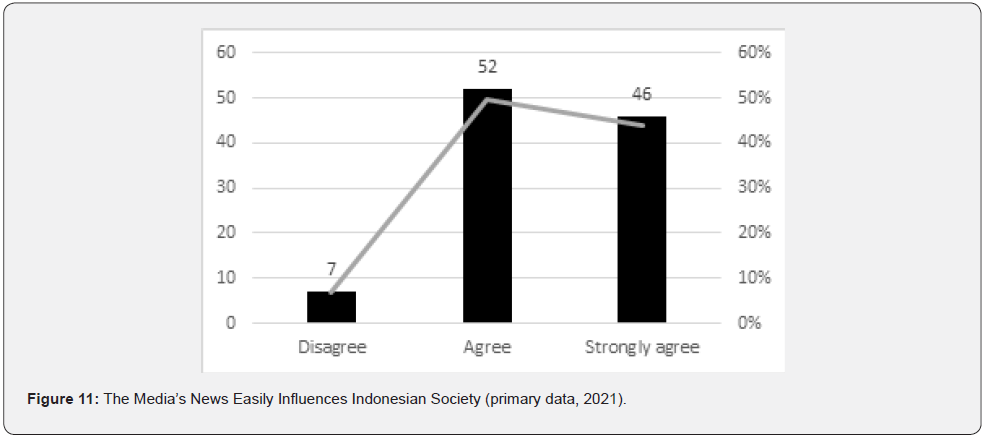

Nevertheless, the survey results demonstrate that the publishing of noncompliance has not supplanted tax incentives as a factor influencing tax compliance. Currently, it can be stated that the comparison is nearly same. 53% of respondents are able to agree that sanctions for publishing of tax noncompliance have a greater impact on taxpayer compliance than tax incentives (33% agree, 20% strongly agree). The remaining 47% of respondents did not agree with this assertion. Given that the technique of naming and shaming has not been fully or effectively adopted in Indonesia, this is very reasonable. However, the fact that some respondents stated that the sanctions for publication of tax noncompliance have a greater impact on the current tax incentives is indicative of the nature of the Indonesian people, who have the potential to support the implementation of this type of public disclosure policy (Figure 11).

The fact that it is simple for Indonesians to create opinions through mass media (and social media) makes it easier to apply the discourse on the application of naming and shaming and achieve its purpose of deterring tax evasion players. The rapid growth of digitalization has contributed to the formation of the social character of society. Although the quick digital flow has the potential for negative effects, it would be highly desirable for the government to maximize the potential positive effects in order to achieve a bigger objective, namely the efficacy of tax society formation efforts.

Public Shaming and Greater Tax Compliance

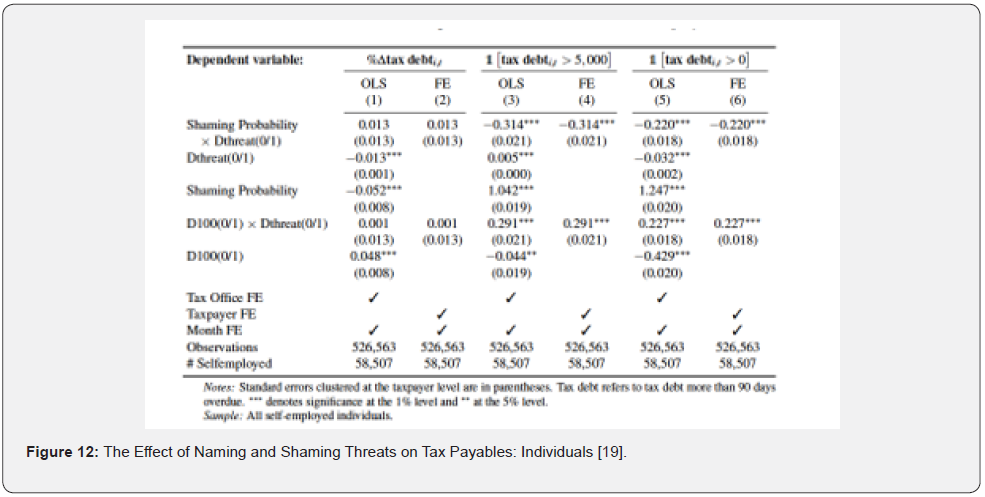

In Slovenia, the successful use of naming and shaming has resulted in reforms in the handling of tax arrears. As a result of the publication of delinquent taxpayer information and data on the tax administration website in April 2013, the ratio of the public accessing the site skyrocketed, reaching 874,301 clicks on 15 April 2013, which is equivalent to 42 percent of the Slovenian population, or 2.06 million people. The increase in searches connected to naming and shaming lists spiked considerably in the week after the publication of the first list. In other words, public concern with the application of naming and shaming to the public is significant [19] (Figure 12).

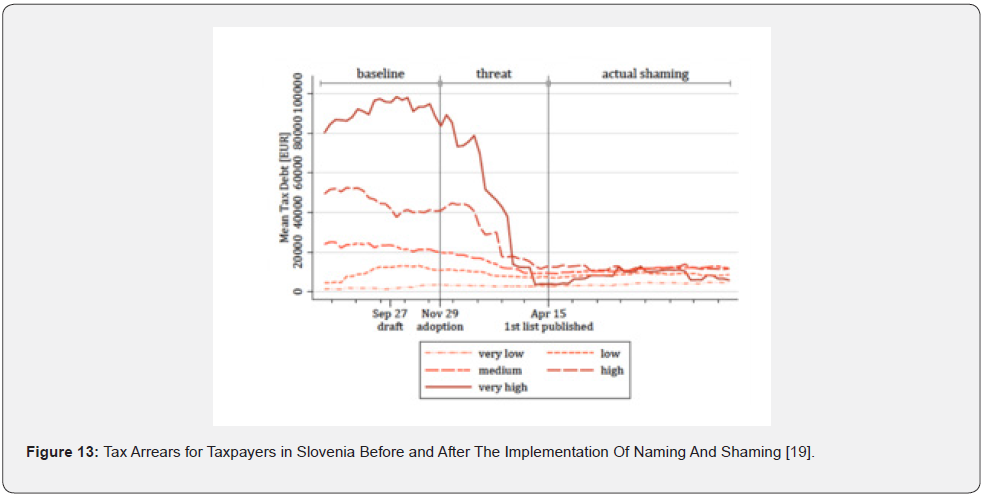

The prospect of public shame is also evident and has affected the tax debt of individuals and business owners. In the picture above, columns 3 and 4 demonstrate that taxpayers who owe more than 5,000 Euros lower their tax debts by 39% when naming and shaming is implemented. This is also consistent with taxpayers whose tax debts are smaller and have decreased to 6.75 percent in columns 5 and 6 [19] (Figure 13).

The figure of the rate of tax arrears also demonstrates the successful application of naming and shaming in Slovenia [19]. The preceding figure indicates that there is a baseline period, which is the time when naming and shaming was created, a threat period, which is the time when naming and shaming is enforced but tax debtors in Slovenia have not been publicly shamed, and an actual shaming period, during which publication or naming and shaming has occurred. A decreased trend in tax arrears, particularly during the actual shaming period, also suggests that tax compliance in Slovenia is on the rise, as seen in the graph [19].

Not only has the application of naming and shaming been successful in Slovenia, but also in one of the developing countries in the Americas, notably Brazil, to promote taxpayer compliance and decrease tax debt. This country’s implementation has demonstrated to have a deterrent effect on noncompliant taxpayers and a favourable effect on tax compliance in Brazil [20].

Based on these two studies, it is possible to hypothesize that the deployment of the naming and shaming technique can reduce tax arrears, offer a deterrent effect for non-compliant taxpayers, and send a warning message to other taxpayers, hence increasing taxpayers’ tax compliance. Naming and shaming have greater potential when employed against individuals and institutions with high net worth. Although it is ultimately applicable to other taxpayer categories.

Regarding limitations, prerequisites, and cost-benefit analysis, it is important to conduct additional research on the implementation of naming and shaming. Aspects of legal protection in tax transparency for taxpayers, authorities, and withholders, as well as international considerations, are also important to study. Considering that taxes is an applied and diverse subject of study, the sociocultural analysis of the possible benefits of implementing the naming and shaming strategy is equally intriguing.

Conclusion

Increasing tax transparency is essential to overcome the traditional problem of tax compliance. Disclosure of tax information is one of the tools used to promote tax transparency between taxpayers and tax authorities. Based on comparative studies conducted in numerous nations that have implemented the naming and shaming method, it has been demonstrated that this strategy has the potential to have a major influence on reducing taxpayer noncompliance, establishing a deterrent effect, and boosting tax morale. As a result, the Indonesian government should explore adopting this strategy to the high-net-worth population as a trial project.

The results of a survey on public opinion regarding the practice of naming and shaming indicate that the majority of Indonesians desire and support its implementation. This is a crucial initial investment for the government if it wants to begin adopting the naming and shaming strategy to gain public support, given that the disclosure of tax information is still regarded as taboo and extreme due to data confidentiality regulations. The naming and shaming method is a novel approach that merits testing to increase taxpayer compliance, particularly in countries with a strong social control culture, such as Indonesia.

To contribute to the improvement of Indonesia’s tax system, the researcher suggests several information disclosure-related measures to increase tax transparency, namely:

a) Before implementing tax information disclosure, the government (tax authority) must have the requisite expertise and capacity to undertake audits of taxpayer data so as not to incorrectly label or categorize taxpayers based on their tax compliance. The government must establish a particular compensation mechanism if it publishes incorrect taxpayer tax information.

b) Prior to determining which category of taxpayers must be subjected to naming and shaming social sanctions, it is necessary to establish an acceptable category based on the amount of debt or tax arrears. In Slovenia, the government publishes information and statistics pertaining to taxpayers who breach tax laws and owe more than €5,000 but have not paid within 90 days. While in Ireland, the government establishes this scheme for taxpayers with tax court cases involving more than one million euro.

c) There should be limitations and prerequisites that must be met before publishing tax data for naming and shaming purposes. These restrictions must be upheld in accordance with legal protection considerations for taxpayers, tax administration, withholding taxpayers, and the context of international taxation. Brazil, Slovenia, and Ireland disclose information regarding taxpayers’ names, addresses, and identity numbers. Ireland also discloses information regarding the taxpayer’s occupation, status, penalties, and violations. According to the poll’s results, people said that their home addresses, phone numbers, total personal assets, names of their parents, and taxpayers’ debts are private information.

Acknowledgements

Thank you for the support from the Faculty of Administrative Sciences, Universitas Indonesia through the Lecturer Development Program of the FIA UI Functional Position Improvement Grant Scheme for the 2021 Fiscal Year.

References

- Yavaşlar FB (2018) Tax Transparency. IBFD, Amsterdam, pp. 017 – 037.

- Dang L, Fickel L (2022) The Impact of Social Information on Behavior: Donation Behavior and Implications for Charitable Organizations Review on the Impact of Social Information. Psychol Behav Sci Int J 18(2): 555985.

- Nurtanzila L, Wahyudi K (2015) Faktor-Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Penerimaan PBB P2 di Kota Yogyakarta Pasca Pelimpahan Kewenangan Pengelolaan PBB P2 Oleh Pusat Kepada Daerah (Factors Affecting Land and Property Tax in Yogyakarta City after the delegation of Authority for Land and Property Tax Management). JKAP (Jurnal Kebijakan dan Administrasi Publik) 19(2): 155.

- Bidara (2021) Mengkhawatirkan, Faisal Basri Sebut Penurunan Tax Ratio Indonesia Paling Parah (Worryingly, Faisal Basri called Indonesia’s Tax Ratio in the Worst Decrease). Nasional Kontan. Paragraph, pp. 005 - 007.

- Nurhidayat D (2021) Rasio Pajak Indonesia Masih Rendah (Indonesia’s Tax Ratio is Remain Low). Media Indonesia, Jakarta, p. 001.

- Misra F (2021) Kontekstualisasi Pilkada Riau: Sosiokultural,Relasi Klientalistik Dan Indikasi Politik Uang (Contextualitation of Riau Pilkada : Sociocultural, Clientalistic Relations, and Indications of Money Politics). Integritas Jurnal Anti Korupsi, Riau, p. 053.

- Auerbach A, Kent S (2017) The Economics of Tax Policy. Oxford University Press, UK, p. 045.

- Rahayu DP (2017) Penyebab Wajib Pajak Tidak Patuh (Causes of Noncompliance Taxpayers). Agregat: Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Bisnis 1(2): 238.

- Susilawati N (2021) Tingkat Literasi Pajak Penghasilan Orang Pribadi dan Determinannya (Studi di Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, dan Bekasi) (Literacy Level of Personal Income Tax and its Determinants (Studies in Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi) Sebatik, Jakarta 25(1): 286-295.

- Meliala ST (2007) Mengapa Masyarakat Enggan Membayar Pajak (Why People are Reluctant to Pay Taxes) Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Katolik Parahyangan, Bandung 11(1): 32.

- Haning MT (2019) The Strategy of Developing Taxpayers Trust in South Sulawesi Province. Jurnal Kebijakan & Administrasi Publik 23(2): 136.

- Pratiwi N (2017) Persepsi Masyarakat Indonesia Soal Pajak (Indonesia’s Public Perception regarding Taxes). DDTC News, 001.

- Yustisia D (2019) Pro-Kontra Naming & Shaming Dalam Pajak (Pro and Cons of Naming and Shaming in Taxes). News DDTC, Jakarta.

- Siahaan, Fadjar OP (2013) The Effect of Tax Transparency and Trust on Taxpayers’ Voluntary Compliance. GSTF Business Review (GBR). p. 005.

- Perez-truglia (2018) Shaming Tax Delinquents. p.245.

- Luttmer (2014) Tax Morale.

- OECD (2017) Fighting Tax Crime - The Ten Global Principles. In: (1st edn), p. 178.

- (2021) Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2021 – Indonesia.

- Dwenger N, Lukas T (2019) Shaming for Tax Enforcement: Evidence from a New Policy. Cepr Page, p. 131.

- Rubinstein F, Gustavo GV (2016) Brazil Closing the Brazilian Tax Gap: Public Shaming, Transparency and Mandatory Disclosure as Means of Dealing with Tax Delinquencies, Tax Evasion and Tax Planning. Issue: Derivatives & Financial Instruments. p. 267.

- Taylor Ed (2018) Owed $526 Billion, Brazil Tries New Tactic on Tax Cheats: Shaming.” Bloomberg Tax, p. 001.

- Morse S (2012) Tax Compliance and Norm Formation Under High-Penalty Regimes. Connecticut Law Review, p. 694.