Middle-School Children’s Perceptions of Nonverbal Behaviors as Sexual Consent: An Exploratory Study

Bruce M King*, Courtney E Sciarro and Robin Kowalski

Department of Psychology, Clemson University, USA

Submission: May 16, 2022; Published: May 24, 2022

*Corresponding author: Dr. Bruce King, Department of Psychology, 418 Brackett Hall, Clemson University, USA

How to cite this article: King B M, Sciarro C E, Kowalski R. Middle-School Children’s Perceptions of Nonverbal Behaviors as Sexual Consent: An Exploratory Study. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2022; 18(5): 555999. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2022.18.555999.

Abstract

Many studies have shown that college students use nonverbal behaviors as signals to infer sexual consent. It is not known when these attitudes first develop. Twenty-one middle school children rated nonverbal behaviors on a 7-point scale as indications of sexual consent (1=Definitely No, 7=Definitely Yes). Mean rankings ranged from 2.6-6.0. Seventeen of the participants gave at least one of the behaviors a rating of 5 (Possibly Yes) or higher, and 9 of 10 boys gave at least one behavior a rating of 6 or higher. Age-appropriate interventions to prevent unwanted sexual activity should begin as early as middle school.

Keywords: Sexuality; Sexual consent; Early adolescence; Nonverbal behaviors; Dichotomous

Introduction

At least 20% of American women will be the victim of rape or attempted rape sometime in their lives [1]. The majority of these assaults are perpetrated by someone the victim knows [2]. To prove rape has occurred, it is necessary to show that there was lack of consent. The problem is that “consent involves a thoroughly subjective element” [3]. Most young people use nonverbal behaviors and signals to convey and infer sexual consent [4,5], which can easily lead to misinterpretation. Many studies have examined people’s perceptions of nonverbal behaviors as signals of sexual consent by having participants rate behaviors, either as a dichotomous “Yes” or “No” choice, or more commonly on a Likert-type scale [4,6-11]. The behaviors rated have ranged from a simple “She smiled at him” to intimate behaviors (e.g., touching breasts or genitals).

While intimate behaviors (e.g., touching breasts) are more likely to be perceived as an indication of sexual consent, non-physical behaviors are seen by many as conveying some indication of consent. For example, among non-physical behaviors, one study found the highest rape-justifiability ratings for when the man paid the expenses, if they went to the man’s apartment, or if the woman asked the man to go out [12]. Studies also have found that men interpret nonverbal behaviors by women to be more sexual than intended [10, 13-16], and are more likely than women to infer consent from the social setting (e.g., being alone in the man’s apartment) [17]. All of these studies used college students as participants. Among high school students who are dating, about 8.2% have experienced sexual dating violence in the previous year [18], yet little is known about how younger individuals perceive nonverbal behaviors as signals of sexual consent.

A qualitative study of 33 high school students found that most believed that similar to college students, sexual consent was typically conveyed by nonverbal cues [19]. No study of high school students has included ratings of nonverbal behaviors as signals of sexual consent. Even less is known about middle school students’ beliefs about consent. This is a time of emerging sexual experiences and attitudes. A study of 14 urban public middle schools in southern California found that 9% of the students had engaged in sexual intercourse [20]. About 25% of young adults can remember “thinking a lot about sex” at age 11-12 [21]. Unfortunately, unwanted sexual contact during early dating experiences is not uncommon [22].

It is likely that middle school students differ from college students in significant ways. As summarized by one researcher, middle school students have had “less experience with dating and sexual encounters and have had fewer opportunities to explore or challenge sexual norms” [22]. We hypothesized that middle-school students, like their older counterparts, would view nonverbal behaviors as indicators of sexual consent but, because of their lack of experience, would rate nonverbal behaviors even higher than college students. It is also important to determine if gender differences regarding nonverbal signals of sexual consent exist in early adolescence.

Methods

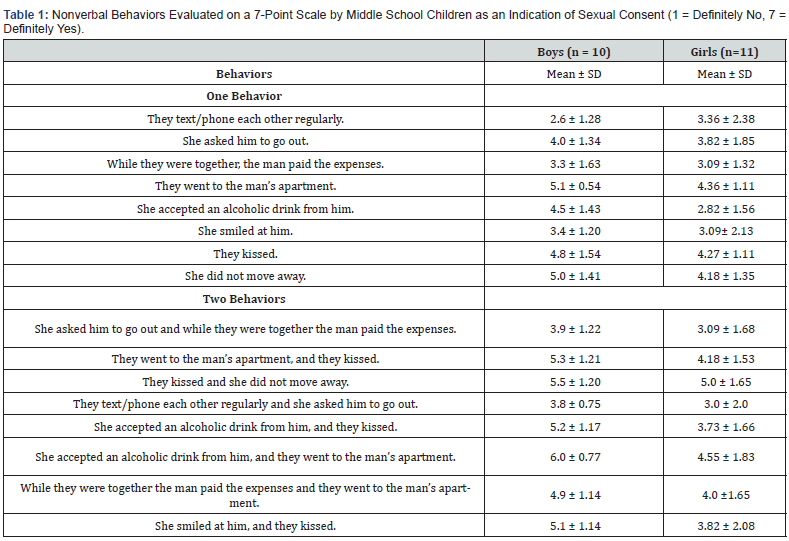

The participants (seventh and eighth grade students aged 12-14 years) were siblings of students enrolled in the senior author’s human sexuality course. Ten boys (eight Caucasian, two Hispanic) and 11 girls (eight Caucasian, one African American, two “Other”) completed the survey. Five others clicked on the survey but did not take it. For these five, it cannot be determined if the middle school children previewed the questionnaire and chose not to take it, or whether their parents previewed it and would not allow their children to take it. The study’s protocol was approved by the university’s IRB. After parental notification, the participants clicked on a link to a Qualtrics survey that allowed them to anonymously answer the questionnaire, which included eight single behaviors and eight combinations of two of those behaviors (Table 1).

The participants were instructed to “imagine that a man and a woman have agreed to go out on a date for the first time” and then to rate each of the behaviors as “an indication that she has given nonverbal agreement to have sex later on the date.” A 7-point Likert-like scale was used. Similar to previous studies in which participants rated nonverbal behaviors as signals conveying sexual consent on a Likert-type scale, the lowest score (“1” here) represented definite non-consent and scores of “2” or higher represented subjectively stronger interpretations of consent, with 7 = Definite Yes. The eight single behaviors chosen for this study excluded intimate touching behaviors, and closely resembled the non-physical behaviors used in previous studies [4,8,11,12]. The only physical contact was simply “They kissed.” The participants were asked to write explanations for their ratings at the end of the questionnaire. Results were analyzed with a mixed two-factor within-subjects ANOVA.

Results

For each participant, a mean was calculated for their ratings of the eight individual behaviors and again for the eight combinations of behaviors. A 2 (Gender) X 2 (Behaviors) mixed model ANOVA revealed no significant effect for Gender (F [1, 19] = 1.948, p = .18, partial omega squared = .094), but statistically significant effects for Number of Behaviors (F [1, 19] = 29.426, p < .0001, partial omega squared = .608) and for the Interaction (F [1,19] = 7.214, p <. .02, partial omega squared = .275). Mean consent was higher for the combination of two behaviors.

The mean ratings (±SD) of each of the eight nonverbal behaviors and eight combinations of behaviors are shown in (Table 1). For 14 of the behaviors, the mean ratings ranged between 3.0 (Possibly No) and 6.0 (Probably Yes). Seventeen of the 21 participants gave at least one of the behaviors a rating of 5 (Possibly Yes) or higher, and 9 of the 10 boys gave at least one behavior a rating of 6 or higher. The single behavior with the highest mean rating was “They went to the man’s apartment” (5.10 for boys and 4.36 for girls). For boys, mean ratings of “Possibly Yes” = 5 or greater were found for five of the eight combinations of two behaviors.

Here are some examples of the participants’ written explanations:

a) “I picked these answers because of what I’ve watched on t.v. shows. That’s what usually happens.” (Boy-rated eight behaviors as “4” or greater)

b) “If she did not move away, they are most likely to have sex.” (Boy-rated 14 behaviors as “4” or greater)

c) “Well, if they kiss then they are obviously close and may want to take it further.” (Boy-rated 14 behaviors as “4” or greater)

d) “I think that if you go to the man’s apartment, then they will conduct sexual activity.” (Girl-rated 10 behaviors as “4” or greater)

e) “Most men ask girls out on a date, which is why I chose that it [“She asked him to go out.”] was more likely.” (Girl-rated 12 behaviors as “4” or greater)

f) “I think that when they went to the man’s apartment it shows they were planning to do something.” (Girl- rated 6 behaviors as “4” or greater)

g) “If they kiss in the apartment then the ‘mood’ might be right.” (Boy-rated 12 behaviors as “4” or greater) [Insert Table 1 about here].

Discussion

The study is limited by the small sample size, but the results are consistent with those of an earlier study of 1,700 Rhode Island middle school children [23]. In that study, 20% of the children answered “Yes” to the question “Does a male on a date have the right to sexual intercourse against the woman’s consent if he spent a lot of money on her.” In another study, nearly 57% of the boys and 27.5% of the girls believed that “A woman who goes to the home or apartment of a man on their first date implies that she is willing to have sex” [24]. One aspect of stereotyped gender roles is traditional sexual scripts, that is, the belief that men are the initiators of sex and women are the gatekeepers [5]. Studies find that many men do not stop sexual advances without a clear verbal signal to stop [25-27]. This includes high school boys [19].

In the present study, there was no overall significant effect for gender (mean ratings collapsed across all behaviors), but similar to the above example [24], there were several behaviors for which the mean ratings by boys far exceeded those for girls. These included “She accepted an alcoholic drink from him” (+1.68), “She accepted an alcoholic drink from him, and they kissed” (+1.47), “She accepted an alcoholic drink from him and they went to the man’s apartment” (+1.45), “She smiled at him and they kissed” (+1.28), and “They went to the man’s apartment and they kissed” (+1.12). Among college students, the use of alcohol by itself is perceived by some as giving consent [4,17]. These high ratings by boys of some nonverbal behaviors as signals of sexual consent may be a contributing factor to the unwanted sexual contact during dating that is already being experienced by young middle school girls [22]. People’s interpretations of nonverbal behaviors as signals conveying sexual consent may differ depending on the relationship history, e.g., two people who have just met, a first date, or two people in a longer romantic relationship [8].

The present study was limited to a man and a woman on a first date. The present results have implications about the development of attitudes regarding sexual consent. The mean ratings by middle school students were greater than mean ratings of similar nonverbal behaviors by college students reported in previous studies. For example, in a previous study of college students who rated similar nonverbal behaviors as signals of sexual consent, 43.1% of the women and 20.3% of the men answered “Definitely No” to all behaviors and combinations of behaviors [11]. None of the middle school children in the present study answered, “Definitely No” to all behaviors, and only one did not rank any of the behaviors greater than “2” (“Probably No”). The difference between the present results and those found with college students suggests that life experiences as one grows older result in fewer people regarding nonverbal behaviors (of the type tested here) as signals conveying sexual consent.

Many colleges have adopted a policy that sexual consent must be given by an unambiguous, verbal “Yes” [28]. While teaching young women sexual assertiveness (promoting “say no”) is an important part of sexual assault prevention programs, program leaders must acknowledge many people’s mistaken beliefs about nonverbal behaviors as signals of consent [8,29]. Programs designed to reduce unwanted sexual contact cannot wait until college, or even high school, but must begin in early adolescence. Levine [22] noted that programs to reduce unwanted sexual contacts between dating peers are generally designed for older students and that program leaders must do more than simply repackage curricula when teaching younger students.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Elenah Rosopa for help with the statistical analyses.

References

- Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Basile KC, Walters ML, Chen J, et al. (2014) Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization - National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries 63(SS-8): 1-18.

- Krebs C, Lindquist C, Berzofsky M, Shook-Sa, Peterson K, et al. (2016) Campus climate survey validation study final technical report. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, USA.

- Hubin DC, Haely K (1999) Rape and the reasonable man. Law and Philosophy 18(2): 113-139.

- Hickman SE, Muehlenhard, CL (1999) “By the semi-mystical appearance of a condom”: How young women and men communicate sexual consent in heterosexual situations. Journal of Sex Research 36(3): 258-272.

- Jozkowski KN, Peterson ZD (2013) College students and sexual consent: Unique insights. J Sex Res 50(6): 517-523.

- Beres MA, Herold E, Maitland SB (2004) Sexual consent behaviors in same-sex relationships. Arch Sex Behav 33(5): 475-486.

- Hall DS (1998) Consent for sexual behavior in a college student population. Electronic Journal of Sexuality 1.

- Humphreys T (2007) Perceptions of sexual consent: The impact of relationship history and gender. J Sex Res 44(4): 307-315.

- Humphreys T, Herold E (2007) Sexual consent in heterosexual relationships: Development of a new measure. Sex Roles 57(3-4): 305-315.

- Jozkowski KN, Peterson ZD (2014) Assessing the validity and reliability of the Consent to Sex Scale. J Sex Res 51(6): 632-645.

- King BM, Fallon MR, Reynolds EP, Williamson KL, Barber A, et al. (2021) College students’ perceptions of concurrent/successive nonverbal behaviors as sexual consent. J Interpers Violence 36(23-24): NP13121-NP13135.

- Muehlenhard CL (1988) Misinterpreted dating behaviors and the risk of date rape. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology 6(1): 20-37.

- Abbey A (1982) Sex differences in attributions for friendly behavior: Do males misperceive females’ friendliness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 42(5): 830-838.

- Jozkowski KN, Peterson ZD, Sanders SA, Dennis B, Reece M (2014) Gender differences in heterosexual college students’ conceptualizations and indicators of sexual consent: Implications for contemporary sexual assault prevention education. J Sex Res 51(8): 904-916.

- Jozkowski KN, Sanders S, Peterson ZD, Dennis B, Reece M (2014) Consenting to sexual activity: The development and psychometric assessment for dual measures of consent. Arch Sex Behav 43(3): 437-450.

- Koukounas E, Letch NM (2001) Psychological correlates of perceptions of sexual interest in women. Journal of Social Psychology 141(4): 443-456.

- Jozkowski KN, Manning J, Hunt M (2018) Sexual consent in and out of the bedroom: Disjunctive views of heterosexual college students. Women’s Studies in Communication 41(2): 117-139.

- Basile KC, Clayton HB, DeGue S, Gilford JW, Vagi KJ, et al. (2020) Interpersonal violence victimization among high school students-Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(1): 28-37.

- Righi MK, Bogen KW, Kuo C Orchowski LM (2021) A qualitative analysis of beliefs about sexual consent among high school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36(15-16): NP8290-NP8316.

- De Rosa CJ, Ethier KA, Kim DH, Cumberland WG, Afifi AA, et al. (2010) Sexual intercourse and oral sex among public middle school students: Prevalence and correlates. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 42(3): 197-205.

- Larsson I, Svedin CG (2002) Sexual experiences in childhood: Young adults’ recollections. Arch Sex Behav 31(3): 263-273.

- Levine E (2017) Sexual violence among middle school students: The effects of gender and dating experience. J Interpers Violence 32(14): 2059-2082.

- Kikuchi JJ (1988) Rhode Island develops successful intervention program for adolescents. NCASA News Pp: 26-27.

- Boxley J, Lawrance L, Gruchow H (1995) A preliminary study of eighth grade students’ attitudes toward rape myths and women’s roles. J Sch Health 65(3): 96-100.

- Goodcase ET, Spencer CM, Toews ML (2021) Who understands consent? A latent profile analysis of college students’ attitudes toward consent. J Interpers Violence 36(15-16): 7495-7504.

- Marcantonio TL, Jozkowski KN, Lo WJ (2018) Beyond “just saying no”: A preliminary evaluation of strategies college students use to refuse sexual activity. Arch Sex Behav 47(2): 341-351.

- Orchowski LM, Gidyez CA, Kraft K (2021) Resisting unwanted sexual and social advances: Perspectives of college women and men. J Interpers Violence 36(7-8): NP4049-NP4073.

- Curtis JN, Burnett S (2017) Affirmative consent: What do college student leaders think about “Yes means Yes” as the standard for sexual behavior? American Journal of Sexuality Education 12(3): 201-214.

- Muehlenhard CL, Humphreys TP, Jozkowski KN, Peterson ZD (2016) The complexities of sexual consent among college students: A conceptual and empirical review. J Sex Res 53(4-5): 457-487.