Will Virtual Reality Increase Children’s Hope, Pleasure, and Travel Expectation?

Pei-Shan Hsieh*

Department of Business Administration, Tunghai University, Taiwan

Submission: October 12, 2021; Published: October 19, 2021

*Corresponding author: Pei-Shan Hsieh, Department of Business Administration, Tunghai University, Taiwan

How to cite this article: Pei-Shan H. Will Virtual Reality Increase Children’s Hope, Pleasure, and Travel Expectation?. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2021; 17(5): 555974. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2021.17.555974.

Abstract

Children between 7-18 years old start to develop curiosity about the world beyond cognition in the process of learning. They have stronger desires to explore the world by themselves. With the gradual maturity of virtual reality (VR) technology, we can reach every place through the immersive experience of VR. We hope to give children a short-term pleasure when experiencing VR, satisfy children’s curiosity, and enhance children’s sense of hope. The experiment is designed to understand the difference in children’s hope after VR experience through the design of the questionnaire before and after the test. Then collect the physiological data through ECG to understand children’s excitement during the VR experience. This study can assist the tourist industry to understand the VR application in children’s expectations for travel. Also, we hope children can keep their hope, expectation, and imagination to face the challenges of the future through the VR experience.

Introduction

Children between 7-18 years old are in a stage of the rapid growth of physical and psychological development. In this stage, children start to learn to understand themselves and develop personal thoughts. However, they will also encounter more complicated restrictions and challenges. Then, they may have more different feelings, including positive or negative emotions. Herth [1] pointed out that hope is a protection factor that can help a person reduce negative effects.

Children start to develop curiosity about the world beyond cognition in the process of learning. They have stronger desires to explore the world by themselves. So, this research hopes to meet the needs of children by using VR, give children a short-term pleasure when experiencing VR, and satisfy children’s curiosity and enhance children’s sense of hope. We hope this study might help children keep their expectation and imagination to face the challenges of the future.

According to the above research background and motivation. The following objectives are proposed in this study.

a) Examine the pleasurable experience of VR applied to tourist destinations for children.

b) Examine the impact of VR application in tourist destinations for children’s hope and expectations.

Literature Review

Hope is a process of cognitive thinking to desired goals [2,3], and scholars point out that hope can increase children's optimism to face themselves and the future. Then encourage children to implement specific actions to achieve goals. Hope also can help individuals stay flexible and have responsive strategies when they encounter major pressure events in life [4]. Also, hope can enhance children’s life satisfaction effectively. The more pressure the children feel, the more to show the functions of hope [5].

Emotion is a transient state that can change drastically in a short time. Also, pleasure is a high-level of positive emotion. According to psychology, pleasure combines the emotion of joy and surprise. Engaging in various activities, such as traveling, watching movies, etc., will bring people a different degree of pleasure. Due to the different degree of immersion, pleasure will cause different levels of positive emotions and self-satisfaction needs [6]. Expectation is the belief that one’s actions can be successfully executed and produce results [7]. And the travel expectation we used in this research is results about what people expect to get while traveling.

Methods

Experimental design

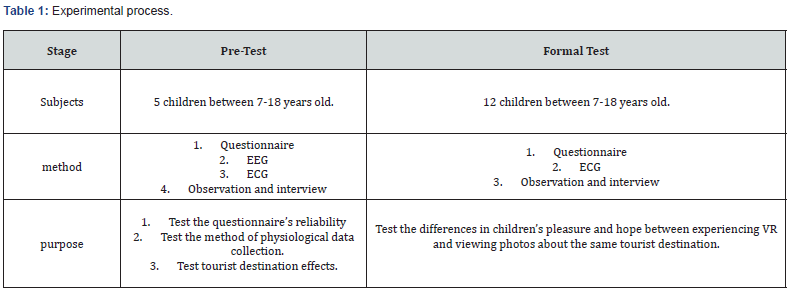

The subjects of this research are children between 7-18 years old. We use the experimental method, and the experiment is designed to understand the difference in children’s hope after VR experience through the design of the questionnaire before and after the test. Then collect the physiological data through electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocardiography (ECG) to understand children’s excitement. The experiment is divided into two stages: pre-test and formal test as Table 1.

We divide children into experimental and control groups. Children in the experimental group will experience the foreign destination before experiencing domestic one. The control group experiences domestic destination first, and then foreign destination. Therefore, every child will experience twice, fill out two questionnaires for different destinations, and collect two sets of physiological data. Regarding the content of VR experience, we provide five domestic tourist destinations and six foreign tourist destinations. Furthermore, we will collect EEG data when children filling in the pre- and post-test questionnaires and collect ECG data during the VR experience.

Measurements

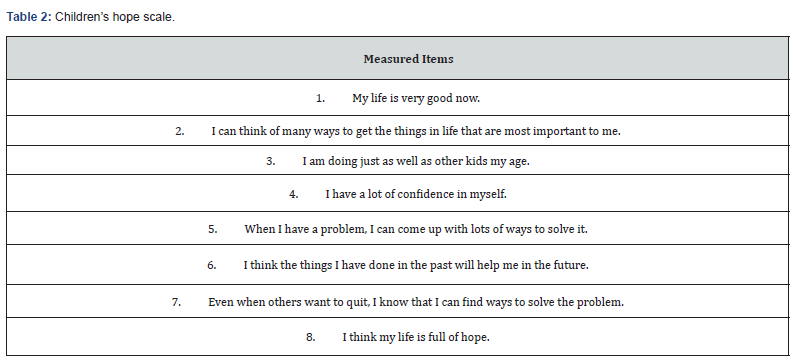

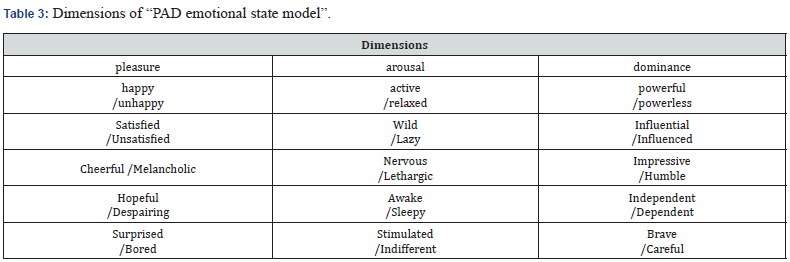

We adopt the “Children’s Hope Scale” which was developed by Snyder et al. (1997) (Table 2). We adopt the “PAD (pleasure, arousal, domination) Emotional State Model” which was developed by Mehrabian & Russell [8]. This model has three dimensions of “Emotional structure model”. They are “arousal”, “pleasure”, and “dominance.” These three dimensions can be described and measured the difference of personal emotion, and have extremely low correlation with each other. If the subject gets higher score from “pleasure” dimension, it means the subject obtains more pleasure from the stimulus (Table 3).

Result

Pre-test results

Five children participated in the pre-test: three boys and two girls. They are all in grades 4-6. The mean of hope is higher in the experimental group than the control group. Also, from the interview, we know that children are not affected by VR tourist destinations and experience order effects, and they are more expected and excited to experience foreign destinations. As a result, we adopt foreign tourist destinations in formal test. Moreover, it is difficult for children to stabilize their brain waves in a short period. It’s a challenge for the researcher to collect complete data. Therefore, EEG won’t be used in the formal test. In terms of ECG measurement, there is no limit to the VR experience time during the pre-test. This resulted in multiple data being less than 11 minutes and unable to analyze. To ensure data integrity, this research will limit the VR experience time to 11 minutes in the formal test.

Formal test result

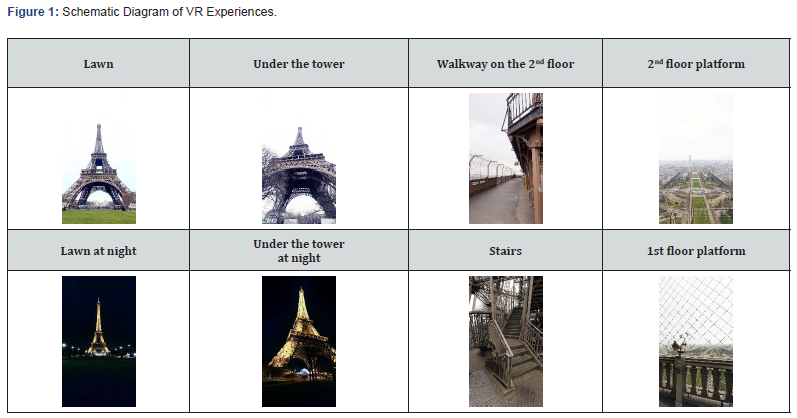

We divide children into experimental and control groups. Children in the experimental group will use VR to experience tourist destinations (see Figure 1). The control group is to experience tourist destinations through photos. “Eiffel Tower” was selected as a tourist destination in formal test, and ECG data collected during VR experience and viewing photos. Descriptive statistics of subjects as Table 4.

Source: “Sites in VR” app

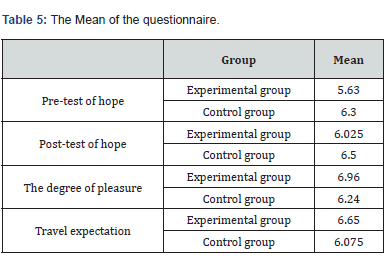

There are three aspects of the questionnaire design of this research. The following Table 5 shows the average statistics of each aspect. First, it can be found that the mean of hope increases more in experimental group (0.395) than the control group (0.2). This means VR brings more hope to the children in experimental group than photos in the control group. In terms of pleasure aspect and travel expectation aspect, the mean in the experimental group is also higher than the control group.

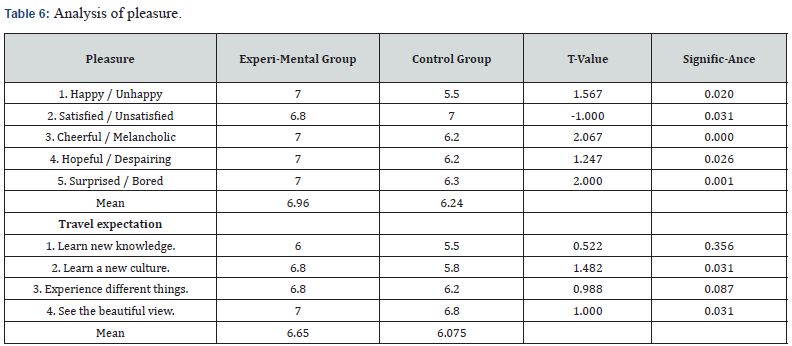

The mean of pleasure measurements and travel expectation are all higher in the experimental group than the control group. According to the t-test, there is significant difference as shown in Table 6. Based on the results of multiple comparison analysis of ECG, many indicators have reached significant differences. The following Table 7 is a description of related indicators.

We speculate the reason for the significant difference is that the VR experience brings greater sense of presence and gratitude to children than photos. This causes the children’s heartbeat to increase and indicates that the children's emotions are relatively excited during this time. This means that the pleasure brought by VR experience is higher than viewing photos.

Conclusion

We found that children get quite high means in the questionnaire of pleasure scale. There are also many indicators in the analysis results of the ECG data that have reached significant differences. This means that the pleasure of experiencing VR is higher than simply viewing photos. Researchers also observed that children show excitement and expectation when they mention tourist destinations they have never visited before, particularly foreign destinations. Children are also quite immersed in the VR experience. They are often excited and surprised by discovering new scenes. After watching VR for 11 minutes, the experience ends, most children feel that the time is too short.

As mentioned above, we can find out that using VR to experience tourist destinations can bring significant pleasure to children. At the same time, it can shorten children’s time experience. Help children to deal with and adjust emotions, and resolve the discomfort and distress caused by negative emotions. This research hopes to understand the impact of VR application in tourist destinations on the hopes and expectations of children. This study conducted a test on 12 children in the formal experimental stage. In the results of the questionnaire analysis, the mean can show the difference, and the data from most of the ECG indicators also showed significant differences.

This study can assist the tourist industry to understand the VR application in children’s expectations for travel. Also, we hope children can keep their hope, expectation and imagination to face the challenges of the future through the VR experience. However, the subjects we collected in this study is not enough, the statistics might have the bias. Therefore, this research is still going on and we continue collecting the subjects.

References

- Herth K (1989) The relationship between level of hope and level of coping response and other variables in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 16(1): 67-72.

- Snyder CR (2002) Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological inquiry 13(4): 249-275.

- Hagen KA, Myers BJ, Mackintosh VH (2005) Hope, social support, and behavioral problems in at‐risk children. Am J Orthopsychiatry 75(2): 211-219.

- Horton TV, Wallander JL (2001) Hope and social support as resilience factors against psychological distress of mothers who care for children with chronic physical conditions. Rehabilitation Psychology 46(4): 382.

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B (2000) The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work.

Child Dev 71(3): 543-562. - Lin A, Gregor S, Ewing M (2008) Developing a scale to measure the enjoyment of web experiences. Journal of Interactive Marketing 22(4): 40-57.

- Bandura A (1977) Analysis of Self-efficacy Theory of Behavioural Change. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1: 287-308.

- Mehrabian A, Russell JA (1974) An approach to environmental psychology. MIT Press, USA.