Gravity, Punishment and Justice : A Clustering Analysis in French Teenagers’ Judgments of Antisocial Acts

Patricia Rulence-Pâques1, Eric Fruchart2, Véronique Leoni1 and Nathalie Przygodzki-Lionet1*

1University of Lille, ULR 4072 - PSITEC, F-59000 Lille, France

2University of Perpignan, Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Performance Santé Environnement de Montagne - ULR 4604, Font-Romeu, France

Submission: March 24, 2021; Published: April 26, 2021

*Corresponding author: Pr. Nathalie Przygodzki-Lionet, Université de Lille, UFR de Psychologie, Domaine Universitaire du Pont de Bois, 59653 Villeneuve d’Ascq, France

How to cite this article: Patricia Rulence-P, Eric F, Véronique L, Nathalie Przygodzki-L. Gravity, Punishment and Justice :A Clustering Analysis in French Teenagers’ Judgments of Antisocial Acts. Psychol Behav Sci Int J .2021; 16(5): 555947. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2021.16.555947.

Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify different positions regarding the way in which 412 teenagers of secondary schools, including 214 young adolescents (Mage = 12.5, SD = 1.5) and 198 old adolescents (Mage = 16.5, SD = 1.5), integrated four informational cues (the level of antisocial behaviour, the consequences in the classroom, the apologies and the teacher’s attitude) for judging the degree of gravity of anti-social behaviour during a Physical Education (PE) lesson. The judgments on the fairness and level of the punishment were also collected. Cluster analyses (K-means), ANOVAs, and chi-square tests were done. Three clusters were observed. The first cluster was called “Intolerance to Aggression”; the second was termed “Depends on Type of act and Apologies” and the third was termed “Tolerance Near Zero”. The relationship between PE and moral judgment is discussed.

Keywords:Adolescents; Antisocial behaviours; Gravity; Punishment; Justice; Moral judgment.

Introduction

Teachers have become more and more concerned about the misbehaviours of some students in class [1]. Psycho-social development and sport are promoted as they could reduce antisocial [2]. Pascual et al. [3] have suggested that physical education lessons are very important for youth’s positive psychosocial development because it requires effort, cooperation, conflict management and relationships with peers and teachers. Physical education lessons can be used as a mean for teaching social and moral values such as the respect for other’s rights and they can be educationally useful to lead to desirable social and moral outcomes [4]. The moral education is therefore related to the moral growth which evolution is linked to cognitive maturation and effects of social interactions [5-8].

Physical Education (PE) being a less competitive environment than sports, one of its main educational goals is to promote moral competence. School looks like a small society that conveys moral values, where children learn what is right or wrong in this particular context [9]. For instance, a set of activities is developed within PE with specific rules. Children will be able to learn what is right or wrong for a lot of issues. Then, they can apply that in their everyday lives. Recent studies have described a positive relationship between morality in PE and daily life. Gutiérrez and Vivó [10] have shown the benefit of an intervention program applied to the context of school physical education for the development of moral judgment in students. Menéndez and Fernández-Río [11] have observed a positive influence of PE programs and development campaigns of values on moral and social development. Sanchez-Alcaraz et al. [12] have shown that students make improvements in personal and social responsibility within a teaching model in education of values through PE lessons. Other studies have highlighted that the appropriateness and the effectiveness of PE can help to initiate aspects of morality such as a) promotion of moral reasoning maturity [13], b) enhancement of pro-social behaviours [14] and c) improvement of moral judgment, intention and behaviour [15].

One can say that moral judgments are based on one’s perception of the rightness or wrongness of specific acts because it is linked to moral questions. As norm violations often lead to punishment, people are expected to judge transgressions of moral rules as serious offences and to evaluate how wrong they are with reference to principles of justice [16]. The seriousness of the offence, level of punishment and its suitability may play a major role in the moral judgment. Although the issue of the students’ misbehaviour was investigated rather in the classroom than in physical education settings [17], physical education is an activity that may allow adolescents to acquire social rules and values [18]. During a PE lesson at school, several variables can influence the moral judgment such as the teacher’s behaviour [19], the type of the antisocial act [20], its consequences [21] and the offender’s apologies [22]. First, teachers may influence student’s moral judgment. Weinstock et al. [19] showed that teachers’ behaviour was important, and that teachers’ encouragements contributed to students thinking critically. Second, schools in general are considered to constitute a learning environment in which students exhibit a variety of behaviours. Negative behaviours are observed, that preoccupied teachers and everyone who work in this context. Third, aaggressive behaviour could be using factors such as Intention and Consequences (i.e., whether a physical act is done intentionally or not, that whether it could physically injure a person). This act is against the rules of the game and can have consequences for the opponent.

On one hand, antisocial behaviour can take several forms in PE lessons. It can be non-aggressive behaviour like cheating, which intends to disadvantage another team, for example by not respecting the size of the goals. Or it can be aggressive acts where the objective is to harm an individual [23]. In order to understand aggression in sport, some researchers [24] made the distinction between hostile and instrumental aggressive behaviours. Hostile aggressive behaviour stands for “angry” aggression intended to hurt someone while instrumental aggressive behaviour is planned and motivated by the desire to achieve a goal. Instrumental aggressive acts are often accepted and encouraged in team sports, whereas the hostile aggressive acts are unacceptable and discouraged [25]. Bushman and Anderson [20] questioned this dichotomy. By referring to strategically employed aggressive behaviour in order to achieve a goal, Anderson and Bushman [26] specified that it involves the intent to harm. In this particular case, harm is a consequence of a bold or assertive act [26]. On the other hand, Helwig, Zelazo, and Wilson [27] introduced the separate issue of whether participants judge according to acts, or to the consequences of the act, that is, the resulting harm. They investigated not only the influence of intentions and consequences on moral judgments but also whether children and adults judge according to the nature of the acts (e.g. hitting or petting animals). The participants were questioned about an “act acceptability” and a corresponding “punishment”. Results showed that children’s punishment judgments were primarily outcome-based whereas older participants were more likely to use an intention rule (if outcome is negative and intention is negative, then punish). Gauché and Mullet [21] also showed that the cancellation of consequences had an impact on the willingness to forgive an aggression and Fruchart and Rulence-Pâques [22] confirmed Darby and Schlenker [28] results that more elaborate apologies from the offender resulted in a more forgiving attitude among participants.

Different methodological processes have been used to understand the moral judgment. Piaget [6] wanted to understand the moral developmental structure in children by asking them about pairs of stories. He investigated whether children’s moral judgments were based on intention or consequence. In contrast to adults’ intention-based judgments, children below 10 years old judged acts and agents according to the consequence. Kohlberg [5] used verbal justifications in moral dilemmas to describe the moral development as a sequence of distinct stages from obedience to authority to morality of egalitarian cooperation. The findings of Helwig, Zelazo, and Wilson [27] were closely replicated by Nobes, Panagiotaki, and Bartholomew [29]: children’s judgments according to the nature of the acts were based on the outcome and their punishment judgments were also primarily outcome-based. However, if the question was rephrased by asking for justifications of judgments, children’s judgments were more influenced by the intention than by the outcome. Their findings indicated that a methodological change affects children’s moral judgments.

The present study applies Anderson [30,31] theoretical framework. More particularly, it aimed at complementing the set of previous studies on moral judgment with another methodological approach. It may add to the knowledge on moral judgment by studying the manner in which individuals consider numerous elements of information and combine them cognitively to give a global moral judgment [32-35]. This theory was applied in sport domain and showed that different positions on moral judgment were observed according to the involvement in the practice of sport [36] and that moral judgment increased according to the young players’ age [36]. With the theory of information integration [30-32], researchers’ goal is to discover which operations of cognitive algebra subjects use to process information in various situations. The originality of this theory comes from the methods. This theory assumes that any moral perception, thought or action is goal oriented and depends on the integration of different information. Anderson [30-32] considers the problem of integration as fundamental, prior to the measurement of stimuli and even to the measurement of responses. In this theory, mathematical description and explanation converge. More than one factor is at the origin of our judgments and actions. This is visible in our daily life. For example, we scold children considering both the misconduct they committed and their intent to commit it. We may consider either punishing or lecturing them depending on the cases. Similarly, minor moral problems such as confessing a mistake or lying are examples of daily conflicts. Thus, our social behaviour is based on multiple determination. The theory of information integration and its methodology extend to all areas of cognitive psychology. This theory of cognition is meant to be a theory of daily life or more precisely a theory of judgments expressed in daily life. Its purpose is to clarify the rules (cognitive algebra) that we use every day to make our judgments. It is possible to explain the individuals’ behaviour once a mathematical model is found to reflect the data. “When an individual integrates information to make a final judgment, a field of external stimuli undergoes three successive operations that are directed for this purpose of the subject: (a) a valuation operation that transforms stimulus into subjective representations; (b) an integration operation that transforms these subjective representations into internal responses; and (c) an action operation that transforms the internal responses into observable responses. This is often done by selecting a level along a scale of judgment” [30].

The interest of this present study is to implement the theory of information integration which methodological process is different from the previous studies. The present study takes place in the school context during a PE lesson. It explores the notions of gravity, punishment and justice together because the relationship between an antisocial behaviour and the seriousness of the offence, the level of punishment and its suitability in the context of sports education has received little attention by researchers. It implements the theory of information integration in the domain of moral judgment in relation to PE. This study is concerned with the way cognitive moral processes evolve during early and middle adolescence. By applying the theory of information integration [31,32], it aimed (a) to examine the effect of four factors – the type of antisocial behaviour [37], the consequences for the classroom [21], the offender’s apologies [22], and the usual teacher’s behaviour [19] – on young students’ judgments on the gravity of the antisocial behaviour, on the appropriateness of punishment, and on the level of punishment, and (b) to explore the extent to which qualitatively different positions exist among them. The first hypothesis was that each of the four factors would have an effect. The judgments were expected to differ depending on the type of antisocial behaviour (i.e., being late vs. cheating vs. instrumental aggression vs. hostile aggression). Hostile aggression would be judged more seriously than instrumental aggression because it falls within the law of sports [37]. The participants’ judgments would be influenced by the apologies: even the simplest apology, without any reparation, can have an important effect on moral judgment [22,38]. The judgments were expected to take into consideration the consequences of the antisocial behaviour [21]. The participants’ judgments were expected to be influenced by the teacher’s attitude [19]. The second hypothesis was that different individual moral positions would be identified [22,36] and that each different moral position would be linked to the age of the participants [5,6,22]. The third hypothesis was that the judgments on gravity, punishment and justice would be correlated in each cluster [27,29].

Material and Methods

Sample

The present study was conducted in a secondary education learning environment. The participants recruited and tested by the authors were early and middle adolescents from secondary schools. They came from families with average or upper average socioeconomic status. The study was explained, and we arranged an appointment. The participants were 412 unpaid volunteers living in the North of France. They were between 12 and 17 years old. They were separated into two groups of students in secondary schools due to the educational system in France: they were 214 young students (100 girls and 114 boys) from “collège” which corresponds to the first four years of secondary school cursus (Mage = 12.5, SD =1.5) and 198 older students (98 girls and 100 boys) from “lycée” which corresponds to the three last years of the secondary school cursus (Mage = 16.5, SD = 1.5). These schools have the similar sports education program.

Material for data collection

The material for data collection consisted of three questionnaires of 32 cards with rating scales. According to Anderson’s method [30], each card contained a hypothetical scenario of about eight lines, a question and a response scale. In the scenario, a sport teacher has organized a tournament for which teams had previously been established. One pupil’s behaviour is antisocial. Each scenario was designed with regard to the following four independent variables: (a) the level of antisocial behaviour (the pupil is late, he is cheating, he is showing instrumental aggression, he is showing hostile aggression), (b) apologies (the pupil apologizes versus he does not apologize), (c) the consequence for the classroom (it is disrupted versus it is not disrupted), (d) the teacher’s attitude (he always punishes versus he never punishes this kind of behaviour). All possible combinations of these types of information led to 32 scenarios (4 X 2 X 2 X 2). One typical scenario was the following: A sport teacher has organized a tournament for which teams had previously been established. One pupil, Frederic, physically aggresses a classmate with the intention to hurt him. He does not apologize. The class is disrupted. The teacher has always punished this kind of behaviour. In the first questionnaire, the dependent variable was the response to the question: According to you, what is the gravity level of Frederic’s behaviour ? Beneath each scenario was an 11-points response scale with “Completely serious” indicated on the right and “Not at all serious” indicated on the left. Each scenario concerned a pupil with a different name. The second questionnaire had the same 32 scenarios and the dependent variable was the response to the question: According to you, which level of punishment would be required for Frederic ? The 11-points response scale ranged from “Not at all high” on the left to “Completely high” on the right. The third questionnaire had the same 32 scenarios and the dependent variable was the response to the question: According to you, is it fair to punish Frederic ? The 11-points response scale went from “Not at all fair to punish” on the left to “Completely fair to punish” on the right. These ratings will be coded in a numerical value (from 0 to 10).

Procedure

Permission to conduct the study was granted by the ethical board of the host university and the headmasters of the participating schools gave their written agreement. The authors informed parents about the scope of the study, and they asked for their consent. All parents allowed their children to participate in the study. Beforehand, a test procedure was carried out to verify that there were no confounding factors for understanding the situations. None the data of the respondents identified difficulties. The data were collected by the researchers under the supervision of the students’ own PE teacher. To minimize students’ tendency to give socially desirable answers, students were informed that their questionnaires would be anonymous and confidential, and researchers encouraged them to be as honest as possible. Each participant was presented with three questionnaires (a questionnaire with a rating scale about the gravity of an antisocial act, a questionnaire with a rating scale about the level of punishment, a questionnaire with a rating scale about the level of justice to punish). The order of the three questionnaires was counterbalanced to avoid a learning effect. Each participant worked in a quiet space and answered by making marks on the response scale between the two anchors. Individually, participants had to read each of the 32 stories describing concrete situations and to rate their answer on the scale. There were two phases according to the methodology of Anderson [30]. The first phase was a familiarization phase. The participant’s task was to identify with the student described and to give an opinion about the level of the type of judgment required in each case. Eight scenarios taken from the set of 32 were presented in order to permit the participants to familiarize themselves with the task, the procedure and the test materials [31]. The 8 scenarios were chosen so as to expose participants to the full range of stimuli. During the following second or experimental phase, the 32 scenarios were randomly administered to participants. Participants provided their ratings at their own pace. The participants were presented with the three questionnaires with the same procedure. The participants took approximately 40 minutes (M = 39, SD = 5) to complete the three questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

Each participant’s rating was converted to a numerical value expressing the distance (number of points, from 0 to 10) between the origin of the scale on the left and the point marked on the response scale. These numerical values were then submitted to graphic analysis and statistical analysis.

i. Firstly, an ANOVA with a design of Participants’ age X Scale X Type of behaviour X Consequences for the classroom X Apologies X Teacher’s attitude 2 X 3 X 4 X 2 X 2 X 2 was performed.

ii. Secondly, as we thought that participants were going to respond in very different ways from one another, a k-means cluster analysis was performed [39] on the raw data from all the participants.

iii. Finally, separate ANOVAs were performed on the data of each cluster for each questionnaire, and Pearson’s chi-square test was conducted. Correlations were done between mean ratings of each cluster in the judgment on gravity and those observed in the judgment on punishment and the judgment on justice.

Results

In the results of the ANOVA with 2 X 3 X 4 X 2 X 2 X 2 design, three Scale X factors two-way interactions were significant (Scale X Teacher’s attitude, F(2, 820) = 75.45, p < .001, ɳ²p = .15; Scale X Apologies, F(2, 820) = 7.80, p < .001, ɳ²p = .01; Scale X Antisocial behaviour, F(6, 2460) = 8.07, p < .001, ɳ²p = .01). Thus, there are differences in participants’ cognitive process whether they judge of gravity, of appropriateness of punish and of level of punishment. Two Age X Scale X factors three way interactions were significant (Age X Scale X Apologies, F(2, 820) = 10.96, p < .001, ɳ²p = .02; Age X Scale X Antisocial behaviour, F(6, 2460) = 5.74, p < .001, ɳ²p = .01). Thus, differences exist according to the age of the participants.

The results of a k-means cluster analysis suggested the tenability of a three or a four-cluster solution. The significance threshold was set at p <.05. In the three-cluster solution, the independent variable Cluster was significant, F(2, 409) = 361.09, p < .001, η²p = .63. The subgroups of a three-cluster solution were significantly different on four factors: Questionnaire X Cluster, F(4, 818) = 15.37, p < .001, ɳ²p = .07; Consequences X Cluster, F(2, 409) = 4.48, p < .02, ɳ²p = .02; Apologies X Cluster, F(2, 409) = 14.27, p < .001, ɳ²p = .06; Antisocial behaviour X Cluster, F(6, 1227) = 28.77, p < .001, ɳ²p = .12.

In the four-cluster solution, the independent variable Cluster was also significant, F(3, 408) = 235.26, p < .001, ɳ²p = .63. The subgroups of a four-cluster solution were significantly different only on two factors: Teacher’s attitude X Cluster, F(3, 408) = 120.09, p < .001, ɳ²p = .46, Antisocial behaviour X Cluster, F(9, 1224) = 69.35, p < .001, ɳ²p = .33.

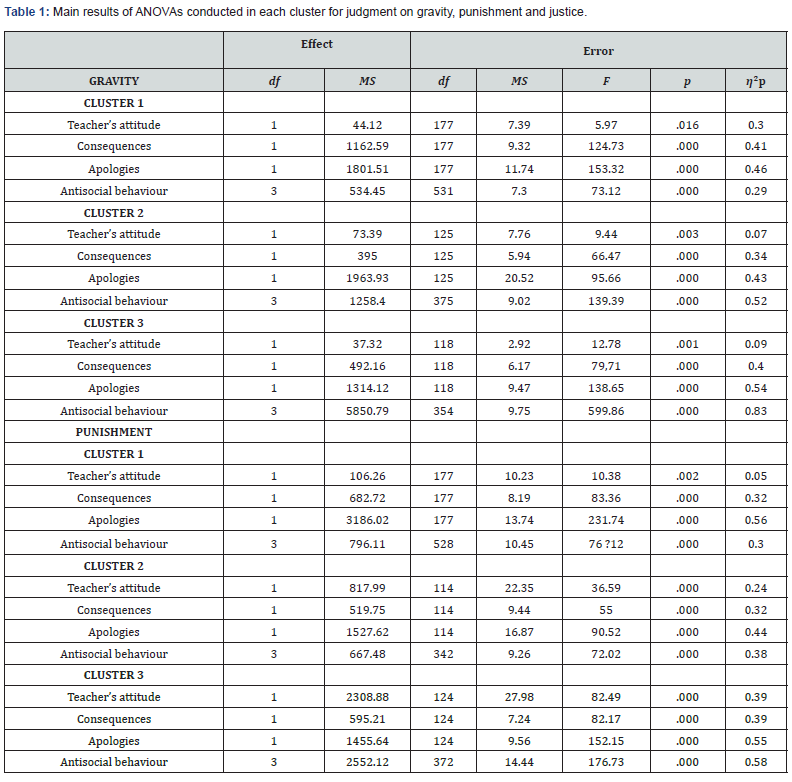

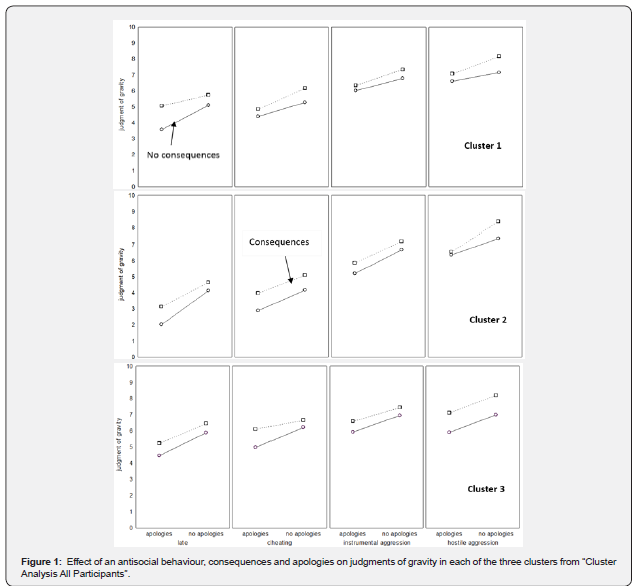

A five-cluster solution has been tested by precaution. The subgroups of a five-cluster solution were not significantly different on each factor. Thus, the subgroups of a three clusters solution provided a best indication for its tenability than the subgroups of a four or a five clusters solution. The three clusters are shown in (Figures 1-3). They present combined effect of antisocial behaviour, consequences and apologies on judgment in each cluster. The choice of this interaction was guided by the fact that these factors were significant (p < .001) in the three clusters. The mean ratings are on the y-axis. The two levels of apologies are on the x-axis. Each curve corresponds to one level of the consequences factor. Each panel corresponds to one level of antisocial behaviour. An ANOVA on the raw data of the “gravity questionnaire” for each cluster and two other ANOVAs respectively on the raw data of the “punishment questionnaire” and of the “justice questionnaire” have been made. The main results are shown in Table 1.

Cluster 1 (n = 79) was termed “Intolerance to aggression”. The judgments on gravity are above the middle of the scale (M = 5.97, SD = .13). It is shown in the four top panels of Figure 1. The curves are separate, which indicates an effect of the consequences. The curves slope, which indicates an effect of the apologies. The curves of both right panels (instrumental aggression and hostile aggression) are above the curves of both left panels (being late and cheating), which indicates an effect of the nature of the antisocial behaviour. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is significant, F (3, 237) = 3.87, p <.01, η²p = .04.

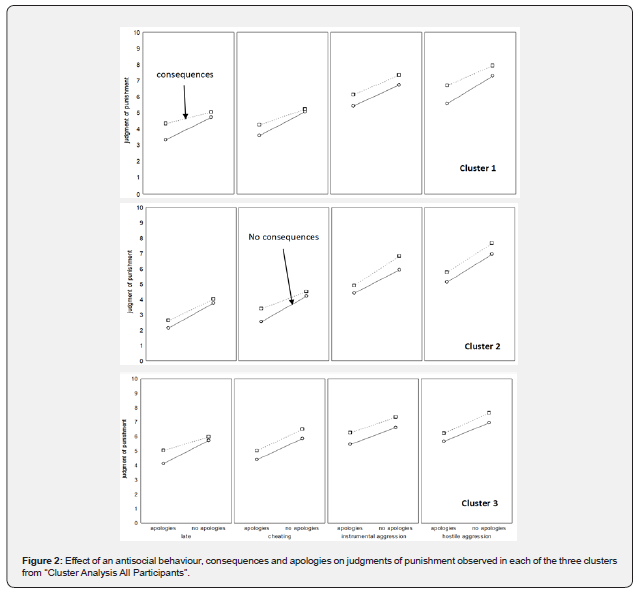

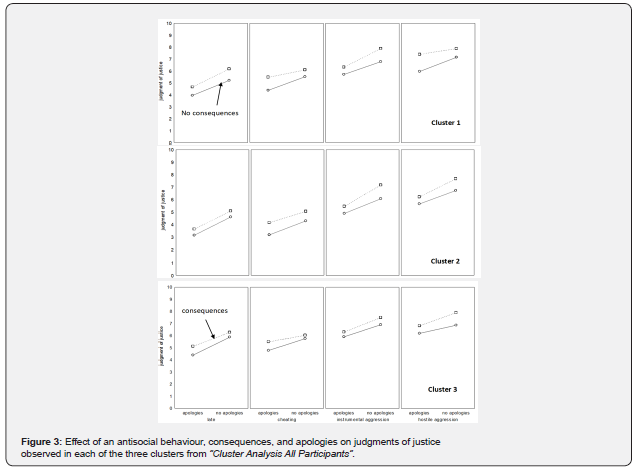

The judgments on punishment are on both sides of the average of the scale (M = 5.53, SD = .12) according to the antisocial behaviour. It is shown in the four top panels of Figure 2. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is not significant, F (3, 237) = .59, p =.61, η²p = .00. The judgments on justice are also on both sides of the average of the scale (M = 6.03, SD = .12) according to the act. It is shown in the four top panels of Figure 3. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is significant, F (3, 237) = 3.21, p <.02, η²p = .03.

Cluster 2 (n = 190) was termed “Depends on Type of act and Apologies”. The judgments on gravity are spread along the entirety of the response scale (M = 5.21, SD = .08). It is shown in the four middle panels of Figure 1. The curves are separate, which indicates an effect of the consequences. The curves slope which indicates an effect of the apologies. The curves rise on the response scale which indicates an effect of the type of antisocial behaviour. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is significant, F (3, 564) = 14.09, p <.001, η²p = .07. The four patterns of judgment on punishment rise on the response scale (M = 4.67, SD = .07). It is shown in the four middle panels of Figure 2. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is significant, F (3, 564) = 5.73, p <.001, η²p = .03.

The curves of judgment on justice were along the response scale (M = 5.18, SD = .08). It is shown in the middle panels of Figure 3. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is significant, F (3, 564) = 3.32, p <.01, η²p = .01.

Cluster 3 (n = 143) was termed “Tolerance Near Zero”. All ratings of judgment on gravity are higher than the middle of the response scale (M = 6.31, SD = .10). It is shown in the four bottom panels of the Figure 1. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is not significant, F (3, 426) = 1.82, p = .14, η²p = .01. The curves of judgment of punishment are higher than the middle of the response scale (M = 5.92, SD = .11). It is shown in the four bottom panels of Figure 2. The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is not significant, F (3, 426) = 1.96, p =.11, η²p = .01. All ratings of judgment on justice are also above the middle of the response scale (M = 6.13, SD = .10). It is shown in the bottom panels of the Figure 3.

The Consequences x Apologies x Antisocial behavior interaction is significant, F (3, 426) = 2.82, p <.03, η²p = .01.

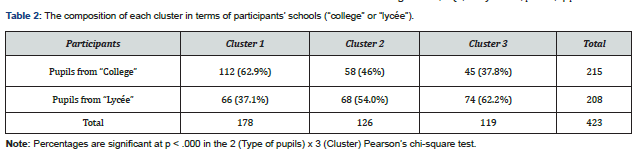

Table 2 shows the composition of each cluster in terms of participants’ schools (“college” or “lycée”). The 2 (students from “college”/students from “lycée”) x 3 (Clusters) Pearson’s chisquare test is significant, χ² (2) = 7.99, p < .000. The first cluster is significatively made up of students from “college” (64.6 %). The second cluster is made up of the same proportion of students from “college” and “lycée”. The third cluster is significatively made up of students from “lycée” (55.2 %).

Correlations have been computed between mean ratings observed in each questionnaire (Gravity, Punishment and Justice) for each cluster. In each cluster, the judgment on gravity is positively correlated with those on punishment (.99, p = .000) and justice (.99, p = .000).

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to examine the moral judgment of adolescents on antisocial behaviour in a school context during a PE lesson. They had to judge the gravity of this antisocial behaviour. They also had to judge the level of punishment for this act, and they had to judge how fair the punishment is. The first hypothesis was that each of the four factors would have an effect. The judgments were expected to differ depending on the type of antisocial behaviour (i.e., being late vs. cheating vs. instrumental aggression vs. hostile aggression). This hypothesis was supported by the results. Unlike being late and cheating, aggressive acts may have severe consequences (e.g., injuries). Thus, the type of behaviour influences the judgments on gravity, punishment and justice. These results show that antisocial hostile aggression is judged as more serious, requires a more severe punishment, that is more deserved, and therefore fairer than instrumental aggression. They show that adolescents understand that antisocial hostile aggression falls within the law of sport activities [37] and the judgments are more salient when the act is viewed as unacceptable [40]. The participants’ judgments were expected to be influenced by the offender’s apologies. This hypothesis was supported by the results. In the judgments on punishment, the apologies were the factor to which the members of the three clusters gave the biggest weight. It confirms a previous study [38]. As the transgressor’s apologies prove that he realizes that his act was transgressive, and that he shows a certain degree of moral understanding, observers are less likely to morally judge him harshly, if he apologies. The participants’ judgments were expected to be influenced by the consequences of the antisocial behaviour. In the three questionnaires, judgments are more severe when an antisocial act disrupts the climate of the classroom. It confirms that the concept of consequences is considered in moral judgment [21,36]. The participants’ judgments were expected to be influenced by teacher’s attitude [19]. This hypothesis is partly confirmed. On the one hand, the results showed a weak effect of the teacher’s attitude on the judgments on gravity and punishment. It can be explained by the fact that young adolescents reify the rules and norms of the adult world as immutable standards for what is good or bad, while older adolescents with increased cognitive and social maturity, become more autonomous and their judgments are more based on individually determined principles. On the other hand, the results showed a higher effect of the teacher’s attitude on the judgment on justice. The adolescents judged that a punishment is all the fairer as the teacher always punished an antisocial act. This result confirmed the importance of model consistency [41] and that the adolescents’ perceptions of their teachers would be positively associated with adolescents’ moral judgment [19].

The second hypothesis was that different individual moral positions would be shown due to the information cues combined differently [22,36] and that the moral position would depend on the age of the participants (e.g. [6,22,42]). That was confirmed. Three positions were identified. The antisocial behaviour, the consequences of this behaviour and the apologies were the information cues principally taken into consideration. Each cluster can be defined by one criteria of judgment concerning antisocial behaviour. Cluster 1 corresponds to “Intolerance to Aggression”. In this latter cluster, the curves divide into two groups. Hostile and instrumental aggressive acts directed toward someone are judged more serious than cheating and being late. These hostile and instrumental aggressive acts are judged to be very serious, require a more severe punishment and the punishment is judged to be very fair. Cluster 2 corresponds to “Depends on Type of act and Apologies” and ratings are spread along the response scale. The judgments of gravity, level of punishment and justice rise gradually according to the type of act. Being late is judged less serious than cheating which is judged less serious than aggressive behaviours. Deliberate aggressive behaviour is judged to be more serious and must be strongly punished, which is completely fair. Cluster 3 corresponds to “Tolerance Near Zero” because all ratings are high in the three questionnaires, whatever the type of behaviour. For all the acts, the participants judge that they are serious, their punishment must be high, and it is always fair to punish. In the three questionnaires of the cluster 3, participants granted a bigger weight to the offender’s apologies. Our findings demonstrated differences in moral judgment. They confirm the special status of antisocial aggressive behaviour within the context of a PE lesson as a physical act that can injure another person with intent to harm [45]. Furthermore, the data supported that the composition of clusters would be linked to the participants’ age (e.g., [6,42]). In the first cluster, the percentage of early adolescents from “collège” schools (64.6%) was higher than the percentage of middle adolescents from “lycée” schools (35.4%). The second cluster was made up of about the same proportion of adolescents from “collège” schools (52.1%) and from “lycée” schools (47.9%). In the third cluster, the percentage of middle adolescents from “lycée” schools (55.2%) was higher than the percentage of early adolescents from “collège” schools (44.8%). This study confirms previous studies on cognitive-developmental morality [6,42]. It confirms that younger students were influenced much more by outcome than by intention [43] and that their punishment judgments were also primarily outcome-based [27,29]. They showed that age was linked to the judgment on the gravity of an antisocial act, to the judgment on the level of punishment required and to the judgment on fairness according to this punishment.

The third hypothesis was that the judgment on gravity would be correlated with the judgments on punishment and fairness. This hypothesis was confirmed in all the clusters. The more the antisocial act was serious, the more it was judged to require punishment and the more the punishment was judged to be fair. There was a link between the judgments on gravity and on punishment although they are very different because evaluating the gravity of an act constitutes simply taking a position on the facts, whilst punishing the author implies a decision making on the future of someone. The judgment on punishment was positively correlated with the judgment on fairness. When the judgment on fairness was more severe, then the punishment required was also judged to be more severe, especially as the participants were older.

These findings reinforce and refine the results from previous studies by exploring the notions of gravity, punishment and justice at the same time. They move forward Anderson’s theory [32] as it applies to understanding students’ cognitions of moral judgments within the PE area. According to these results, students judge that antisocial behaviour during a PE lesson transgress the norms of the group. Students consider it should be punished as they judge it severely and corresponding punishment is judged to be fair. This moral judgment is age sensitive. Applying these results to societal norms can help to understand the relationship between antisocial behaviours and morality, because it is characterized by deviations from societal norms and insensitivity towards other people’s interests. It affects the social cohesion and fragments shared values [44]. Apologies play a major role in the participants’ judgments. This could explain the propensity to forgive that we see in everyday life. If the “offender” apologies for his antisocial behaviour, he gets the occasion to explain the conditions under which the event occurred as well as the reasons why he misbehaved. Therefore, people are more likely to understand and forgive [43]. Understanding the link between behaviours, apologies and forgiveness could help to restore good connections between people. The climate of the classroom influences the students’ judgments. A distasteful mood in the classroom can have a negative effect on the characters of the students [46]. We noted that teacher’s behaviour is especially important for the judgment on justice. School is the first social institution which students are exposed to. Experiencing the teacher’s justice is therefore very important for them and they learn about the legitimacy of authority. Fairly teachers treat them, the more legitimate they will see the school authorities, and they will generalize their experiences to other societal areas [47].

This study emphasizes that physical education at school can significantly contribute in acting more morally. In the context of a PE lesson, the three positions outlined in this research reflect the heterogeneity of the judgments. Initiate a discussion with adolescents on this subject would lead to stimulating debates. Concrete situations in physical education provide an interesting starting point for a debate and can be analyzed in terms of rules and moral principles upon which they are based. The teacher of physical education can use a positive approach in moral judgment by encouraging his students to analyze or reflect on their feelings. He can encourage them to find how they could improve themselves and their practice. He can encourage them to think about their behaviours by asking what they “could do”, not simply what authorities say they “should do”. These guidelines provide the criteria for acceptable conduct [48].

Limitations

As limitations, we can mention the question of the operationalization of two of our factors, the “type of antisocial behaviour” and the “teacher’s attitude”. Effectively, the type of antisocial act is confused with the notion of intention while these two informational cues must be distinguished. For example, a pupil can be late inadvertently or voluntarily; it is also possible to cheat by ignoring the specific rules of the game. Moreover, the weak effect of “the teacher’s attitude” factor is surprising because many studies have shown that moral prescriptions are acquired through the observation of parental and teacher models [41,49]. This result may be explained by the fact that information about the teacher refers to his « habitual » attitude and not directly to the scenario. In future research, more information about teacherstudents interactions needs to be gathered to capture this effect.

Although a test procedure was carried out, a confounding between type of antisocial behaviour and consequences for the classroom may be possible. No test participants indicated to that some scenarios did not seem credible. Nevertheless, how do you explain that an antisocial behaviour has occurred and that it had no consequences on the group? Firstly, it may be explained by the fact that we are on a sports ground where the antisocial behaviour is a part of the game and the consequences are implicitly accepted. Antisocial behaviour is often perceived positively in sports, especially when it leads to successful outcomes and team performance [50]. Secondly, poor student behaviour is a growing concern in the education system, and discipline policies and practices are ineffective and inconsistent. Our children are not only watching us, but they are also behaving in the ways in which we model behaviour for them [51]. Thirdly, in our society, adolescents watch organized sporting events on television which are tinged with competitiveness and individualism. Many studies have focused on the constituents of individualism as descriptive norms in Western societies [52] and many researchers share the idea that ‘‘individualism, independence and autonomy are valued traits in western societies’’ ([53] p. 277). While evaluating the practices observed in early childhood institutional contexts, Branco [54] denounced the preponderance of competitive and individualistic practices and values along childhood educational experiences, and alerts for their dangerous impact on human development. From such a perspective, it appears that people within a same cultural environment may have something in common, meaning their characteristics are fundamentally different from those living in a different cultural environment. Future research could take that into consideration.

Conclusion and implications

This study highlights that future research would be beneficial to access the influence of PE teachers on moral development. First of all, a questionnaire with similar situations would be completed by the students. It would allow to map out their moral judgments. Then, a PE program would be implemented to improve moral and social judgment. Lastly, other fictional situations in a PE context would be proposed to determine if there has been any change in their ideas of morality. Students and teacher could therefore discuss, debate and decide on some rules of conduct, which would be applicable to all during PE lesson. Thereby, sports teachers’ attitudes might be an important factor in promoting the adolescents’ moral judgment and development. According to Hoffman [55], the acquisition of moral rules depends on observational learning but also on the nature of educational practices, and he discusses some implications for socialization and moral education [56]. Some of his recommendations, taken up in schools (e.g. [57] in France), could be generalized in the PE context. Socialization begins at home and continues through the rest of one’s education. The socialization experiences are integrated and increase the sense of fairness and concern for others. During adolescence, pupils are more ‘‘formally’’ introduced to moral principles that are supposed to guide behaviour. One may analyze, interpret, compare and contrast, and accept or reject them and thus construct one’s own set of general moral principles. In the PE context, individuals are active in constructing and understanding moral rules, using information communicated by adults. Therefore, sports teachers’ attitudes can help young people to classify certain acts as morally wrong, unfair, and these acts can educate them about more general principles of justice.

Conflict of Interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Donat M, Dalbert C, Kamble SV (2014) Adolescents’ cheating and delinquent behavior from a justice-psychological perspective: the role of teacher justice. European Journal of Psychology of Education 29: 635-651.

- Hellisson D (2011) Teaching personal and social responsibility through physical activity (3rd) Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, United States.

- Pascual C, Escarti A, Llopis R, Gutierrez M, Marin D, et al. (2011) Implementation fidelity of a program designed to promote personal and social responsibility through physical education: a comparative case study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 82: 499-511.

- Petitpas AJ, Cornelius AE, Van Raalte JL, Jones T (2005) A framework for planning youth sport programs that foster psychosocial development. The Sport Psychologist 19(1): 63-80.

- Kohlberg L (1976) Moral stages and Moralization: the cognitive developmental Approach. In: T. Lickona (Ed.), Moral development and behavior: Theory, Research and Social Issues. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, United States.

- Piaget J (1932) The moral judgment of the child.: Harcourt, Brace, Oxford, England, United States.

- Surber CF (1982) Separable effects of motives, consequences and presentation order on children's moral judgments. Developmental Psychology 18: 257-266.

- Turiel E (1998) The development of morality. In: W Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology. Wiley, New York, United States.

- Proios M, Doganis G, Proios M (2006) Form of the athletic exercise, school environment, and sex in development of high school students’ sportsmanship. Percept Motor Skill 103: 99-106.

- Gutiérrez M, Vivó P (2005) Teaching Moral reasoning of Physical Education school. European Journal of Human Movement 14: 1-22.

- Menéndez JI, Fernández-Río J (2016) Violence, responsibility, friendship and basic psychological needs: effects of a Sport Education and Teaching for Personal and Social Responsibility program. Journal of Psychodidactics 21 : 245-260.

- Sanchez-Alcaraz BJ, Gomez-Marmol A, Valero-Valenzuela A, De La Cruz Sanchez E, Moreno-Murcia JA, et al. (2018) Teachers’ perceptions of personal and social responsibility improvement through a physical education-based intervention. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 18: 2272-2277.

- Mouratidou K, Goutza S, Chatzopoulos D (2007a) Physical education and moral development: An intervention program to promote moral reasoning through physical education in high school students. European Physical Education Review 13: 41-56.

- Battistich V, Solomon D, Watson M, Solomon J, Schaps E (2002) Effects of an elementary school program to enhance pro-social behavior on children’s cognitive-social problem-solving skills and strategies. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 10: 147-169.

- Mouratidou K, Chatzopoulos D, Karamavrou S (2007b) Moral development in sport context. Utopia or Reality? Hellenic Journal of Psychology 4: 163-184.

- Nichols S (2002) Norms with feeling: Towards a psychological account of moral judgment. Cognition 84: 221-236.

- Kulinna PH, Cothran DJ, Regualos R (2006) Teachers’ reports of student misbehavior in physical education. Research Quaterly for Exercise Sport 77: 32-40.

- Weiss MR, Smith AL, Stuntz CP (2008) Moral development in sport and physical activity: Theory, research, and intervention. In: T. S. Horn (Eds.), Advances in sport psychology Champaign, Human Kinetics, IL, United States pp:187-210.

- Weinstock M, Assor A, Broide G (2009) Schools as promoters of moral judgment: the essential role of teachers’ encouragement of critical thinking. Social Psychology of Educatio 12: 137-151.

- Bushman BJ, Anderson CA (2001) Is it time to pull the plug on the hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review 108: 273-279.

- Gauché M, Mullet E (2005) Do we forgive physical aggression in the same way that we forgive psychological aggression? Aggressive Behavior 31: 559-570.

- Fruchart E, Rulence-Pâques P (2016) Condoning aggressive behaviour in sport: A cross-sectional research in few consecutive age categories. Journal of Moral Education 45: 87-103.

- Stephens DE (1998) Aggression. In: JL Duda (Eds.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement. Fitness Information Technology, Morgantown, WV, pp. 277-294.

- Buss AH (1961) The psychology of aggression. Wiley, New York, United States.

- Loughead TM, Leith LM (2001) Hockey coaches’ and players’ perceptions of aggression and the aggressive behavior of players. Journal of Sport Behavior 24: 394-407.

- Anderson CA, Bushman BJ (2002) Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology 53: 27-51.

- Helwig C, Zelazo PD, Wilson M (2001) Children’s judgments of psychological harm in normal and noncanonical situations. Child Development 72: 66-81.

- Darby BW, Schlenker BR (1982) Children’s re-action to apologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 43(4): 742-753.

- Nobes G, Panagiotaki G, Bartholomew KJ (2016) The influence of intention, outcome and question-wording on children’s and adults’ moral judgments. Cognition 157: 190-204.

- Anderson NH (1996) A Functional Theory of Cognition. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, United States.

- Anderson NH (2008) Unified Social Cognition. New York: Psychology Press.

- Anderson NH (2019) Moral Science. Taylor & Francis Ltd, United Kingdom.

- Hommers W, Anderson NH (1989) Algebraic schemes in legal thought and in everyday morality. In: H Wegener, F Lösel, & J Haisch (Eds.), Criminal behavior and the justice system: psychological perspectives, Springer-Verlag, New York, United States, 136-150.

- Leon M (1980) Integration of intent and consequence information in children's moral judgments. In: F Wilkening, J Becker & T Trabasso (Eds.), Information integration by children. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, United States.

- Przygodzki N, Mullet E (1993) Relationships between punishment, damage and intent to harm in the incarcerated: an information integration approach. Social Behavior and Personality 2(2): 93-102.

- Fruchart E, Rulence-Pâques P (2014) Condoning aggressive behaviour in sport: a comparison between professional handball players, amateur players, and lay people. Psicologica 35: 585-600.

- Kerr JH (2002) Issues in aggression and violence in sport: the ISSP position stand The Sport Psychologist 16: 68-78.

- Hommers W, Anderson NH (1985) Recompense as a factor in assigned punishment. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 3: 75-86.

- Hofmans J, Mullet E (2013) Towards unveiling individual differences in different stages of information processing: A clustering-based approach. Quality and Quantity 47: 455-464.

- Widmeyer WN, Dorsch KD, Bray SR, McGuire EJ (2002) The nature, prevalence, and consequences of aggression in sport. In: J. M. Silva & D. E. Stevens (Eds.), Psychological foundations of sport Boston: Ally & Bacon, pp.328-351.

- Bandura A (1977) Social Learning theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood, New Jersey, United States.

- Kohlberg L (1969) Stage and sequence: The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In : DA Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research. Rand McNally College Publishing Company, Chicago, USA pp. 347-480.

- Przygodzki N, Mullet E (1997) Moral judgment and Aging. European Review of Applied Psychology, 47(1): 15-21.

- Squires P, Stephen DE (2005) Rougher justice: antisocial behaviour and young people. Willan Publishing, Cullompton, UK.

- Russell GW (2008) Aggression in the sports world: a social psychological perspective. Oxford University Press, New York, United States.

- Williams KM, Nathanson C, Paulhus DL (2010) Identifying and profiling scholastic cheaters: their personality, cognitive ability, and motivation. Journal of Experimenal Psychology Applied 16: 293-307.

- Gouveia-Pereira M, Vala J, Palmonari A, Rubini M (2003) School experience, relational justice and legitimation of institutional authorities. European Journal of Psychology of Education 28: 309-325.

- Knapp S, Gottlieb MC, Handelsman MM (2018) The benefits of adopting a positive perspective in ethics education. Training and Education in Professional Psychology 12(3): 196-202.

- Leon M (1984) Rules mothers and sons use to integrate intent and damage information in their moral judgments. Child Development 55: 2106-2113.

- Young K (2004) Sporting bodies, damaged selves: sociological studies of sports‐related injury. Elsevier, Oxford, England, United Kingdom.

- Martell LT, Nevarez L (2016) Awareness, prevention, and intervention for elementary school bullying: the need for social responsibility. Children and Schools 38(2): 67-69.

- Oyserman D, Lee SPW (2008) Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin 134: 311–342.

- Lorenzi-Cioldi F, Chatard A (2006) The cultural norm of individualism and group status: Implications for social comparisons. In: S. Guimond (Ed.), Social comparison and social psychology: understanding cognition, intergroup relations, and culture, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK pp.264–282.

- Branco AU (2009) Why dichotomies can be misleading while dualities fit the analysis of complex phenomena. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 43(4): 350-355.

- Hoffman ML (1983) Affective and cognitive processes in moral internalization. In: ET Higgins, DN Ruble, WH Hartup (Eds.), Social cognition and social development: a socio-cultural perspective Cambridge University Press, London, United Kingdom pp.236-274.

- Hoffman M L (2000) Empathy and moral development. Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press, New York, United States.

- Pagoni-Andréani M (1999) Socio-moral development: from theories to civic education. Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, France.