Social and Labor Stressors Influencing Disability in Adult Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity

Dimitri Marques Abramov1,2*, Marjorie Mastellaro Baruzzi2, Renata Joviano Alvim1, Ana Carolina Moda Nunes Peixoto3, Victor de Souza Mannarino4, Caroline Barros Pacheco Loureiro1, Danilla Ferreira1, Iara Almeida5, Ingrid Pinheiro1 and Rosângela Marques Valentim1

11Laboratory of Neurobiology and Clinical Neurophysiology, Fernandes Figueira National Institute of the Woman, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazil

2Department of Mental Health, Petropolis Medical School, Arthur Sá Earp Neto University Centre, Petrópolis, Brazil

3School of Psychology, Maria Auxiliadora Salesian Faculty, Brazil

4Rio de Janeiro Psychiatric Centre, Três Rios, RJ, Brazil

5School of Medicine, University of Vassouras, Brazil

Submission: September 04, 2020;Published: October 14, 2020

*Corresponding author: Dimitri MAbramov, Laboratory of Neurobiology and Clinical Neurophysiology, Fernandes Figueira National Institute of the Woman, Child and Adolescent Health, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation; Avenida Rui Barbosa, 716, Flamengo, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

How to cite this article: Dimitri M A*, Marjorie M B, Renata J A, Ana C M N P, Victor d S M and et al. Social and Labor Stressors Influencing Disability in Adult Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity. Psychol Behav Sci Int J .2020; 15(4): 555919. DOI:10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555919.

Abstract

Background: The Attention Defict/Hyperactivity Disorder remains a controversial issue, although there are many evidences that it is a biologically defined mental entity. If ADH profile represents a mental disorder, it must be the cause of a primary dysfunctionality and maladaptation.

Aims This study aimed to explore adaptability and functionality among ADH(+) subjects from general population in different professional settings.

Methods: We conducted an online survey about economic and academic performances and maladaptation, following a screening for ADHD using Adult Self Report Scale (ASRS). The subjects were naive.

Results: There were 2173 participants, of which 28.06% were ADH(+). Even regarding only subjects with extreme ASRS scores (<1.0 and >2.5), ADH(+) and (-) groups did not shown difference in functionality. We grouped subjects by professional career. The highest ADH(+) prevalence was found in publicity, where almost no difference in subjective suffering between the groups was observed. High women and ADH(+) prevalence can be due convenience recruitment.

Conclusion: In any scenarios, ADH(+) people show equivalent functionality than ADH(-), and also adaptability in their preferred professional settings, arguing that dysfunctionality and mental suffering in ADHD could be influenced by social stress.

Keywords:Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder;Social stress;Labor stress;Functionality;Adaptability; Adult ADHD Self Report Scale;Profession.

Introduction

An appropriate definition of mental disorder is a maladaptive process secondary to the failure of an underlying system to perform functions as determined by evolution [1]. Under this rationale, the DSM-5 defines mental disorder as the manifestation of a dysfunctional and maladaptive mental process [2]. Epistemological discussions about the determinants of this nosology have already lasted decades, since it is argued that the normative, cultural, and moral constructs of our world define what mental disorders are [1,3]. Individual singularities would manifest incompatibilities and consequent suffering with a system of hegemonic norms [4,5]. The relationship between suffering in people with a psychiatric diagnostic and social stress is known. Consequences are linked to mental health-related stigma and discrimination in patients, e.g. loss of self-esteem, self-efficacy, and negative responses such as fear, rage, or guilt [6]. Interventions have been proven to reduce mental illness related to stigma and discrimination [7,8]. A major source of discussion throughout society is Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Despite the evidence that ADHD is a biologically well- defined phenomenology [9-11], its pathological character is quite controversial, both inside academic walls [12-13] and according to common sense [14]. Nevertheless, ADHD is organized as a mental disorder in DSM while there is significative impairment. Therefore, this impairment might be related to the inability of the social system to hold cognitive diversity.

Far beyond these discussions, it is well known that people who manifest ADHD in childhood or adulthood suffer lifelong consequences. Several studies correlate ADH with risky and impulsive behaviors as well as sociopathic profile [15,16], higher incidence of drug addiction [17], and mostly some impairment in social, economic, and academic functioning [18,19]. However, a more complex approach would be required to discuss if these findings are primarily inherent to ADHD or if they could be secondary to the social stress since childhood. Through naive participants screened as ADH(+) or ADH(-) by Adult ADHD Self- Report Scale, short version – ASRS [20-23], our goal was to verify whether (1) academic and economic performance, a functionality parameter (coded as d810-839 and d850 by International Code of Functioning, WHO, 2001) [24], as well as the manifestation of subjective suffering (related to work or not) were different in these two populations. We also accessed these dimensions by professional careers to verify if in some context ADH(+) people show functionality and adaptability equivalent to ADH(-) ones. For instance, if there are working/professional environments where ADH(+) subjects show functionality and adaptability equivalent to typical people, we have an indirect evidence that ADHD, as described by DSM-5, could not be a proper mental disorder but alternatively a circumstantial condition of mental suffering, secondary to maladaptive social and work stress since childhood.

Methods

Subjects

Participants were invited to answer an online survey on “Relationships between Behavior, Health, and Working Life”, did not mentioning ADHD. Therefore, all participants were naive. Participation was completely anonymous and there was no link with the participants’ identities. They gave their consent after reading respective information on first questionnaire page. This work and the procedures adopted were duly approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our Institute under national laws and in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Questionnaire and its application

The questionnaire had 45 questions in Portuguese about objective social functionality (scholarship and incomes), work satisfaction, self-perception of clinical and mental problems (subjective suffering) and psychic treatments. We asked about their technical and/or academic professional careers. They answered a self-assessment questionnaire containing the six items from the short version of ASRS, the WHO assessment for ADHD screening, in questions 15 to 20. Following it, many distractor questions were presented to mask the re-presentation of ASRS questions number 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 into questions 29, 37, 32, 35, and 45, respectively (to infer directly about the individual consistency of answers). The form did not induce forced responses (Table 1). The original questionnaire and datasets can be accessed at http:// data.mendeley.com (http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/s9sdxddnnx.1)

Data analysis

The main analyses were based on screening according to ASRS (short version with six questions). To classify as ADH(+), the ASRS score (average) must be equal to or higher than 1.6. To calculate it, questions 1 to 3 have a weight of 1.2, while questions 4 to 6 have a weight of 0.8 (World Health Organization, 2004). In a preliminary analysis, we observed a significant correlation between age and incomes (see results). Therefore, to normalize income by eliminating age bias, we created a derived variable that is income. The number of clinical and psychic problems per participant were computed as three new quantitative variables.

To infer reliability of ASRS answers, which form a small and two-dimensional cluster (4 questions for inattention and 2 for hyperactivity / impulsivity), Cronbach’s alpha index was calculated [25,26]. We regarded α ≥ 0.60 as ideal [26]. We also established a direct individual consistency index (D) to assess the reliability of each questionnaire individually, using the equation:

Where a is the five-element vector with ASRS answer scores 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6, shown for the first time, and a’ is the vector with the scores of these answers when shown for the second time. We arbitrarily selected subjects with D ≥ 0.75 (75%) as reliable. We studied subgroups, which are: (1) scores lower than or equal to 1, and higher than or equal to 2.5, to increase accuracy of ADHD detection; (2) ADH(+) and (-) that never were submitted to therapies; (3) inside professional settings with higher and lower ADH(+) prevalence; and (4) a randomized and stratified subsample regarding scholarship categories. The first 206 answers were excluded for analysis because we realized online alterations on questionnaire. See raw data in dataset at supplementary information.

Statistical analysis

To compare ASRS scores, age, and number of clinical and mental problems between ADH(+) and ADH(-) groups, we used the T-test for independent samples. For the other variables, regarded as scalar or binary, we adopted the Mann-Whitney U and Fischer’s exact tests, respectively. Correlation analyzes were performed between the ASRS score and continuous (age), scalar, and dichotomous variables using Pearson, Spearman, and pointbiserial correlation methods, respectively. Participants were clustered by professional careers. To infer if ADH(+) prevalence in each cluster is different from the expected one, we used chisquare test for categorical variables:

Where O is the total number of ADH(+) participants in thecurrent cluster, and E is the number of subjects in the cluster times the rate of ADH(+)/total subjects (prevalence). For inference, we regarded one degree of freedom (if ADH(+) or not). We rank the professional settings by χ2 coefficient in descending order, selecting all with p < 0.1 to form two groups of professions (with higher and lower ADH(+) prevalence).

To evaluate the effect size of correlations, we used Cohen’s proposed thresholds for psychosocial sciences [27]. The magnitude of the difference between groups was estimated in terms of rates (0 to 100%), i.e., 1 – (smaller value / larger value), and it was considered when differences are statistically significant

Results

Sample description

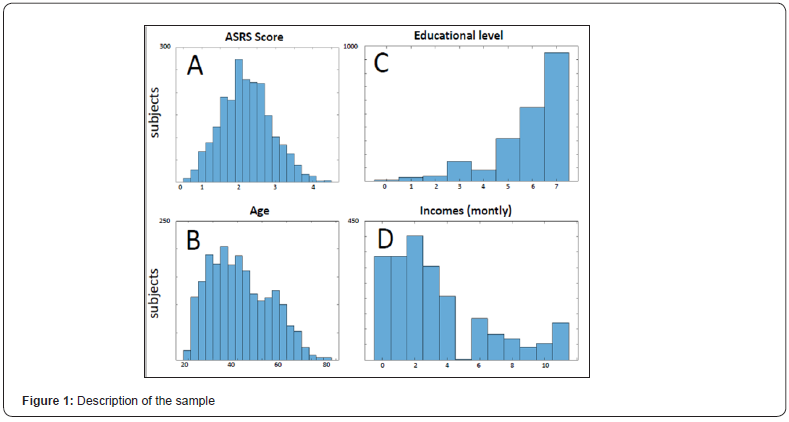

We collected a total of 2173 questionnaires. For ASRS questions, Cronbach’s alpha index was 0.67, regarded as suitable. Only 13 subjects left ASRS questions unanswered. The D index was 0.92 ± 0.06, with only 33 subjects excluded (D> 0.75). The total number of subjects included was 2126, with 1530 screened as ADH(-) and 596 screened as ADH(+), revealing a total prevalence of 28.03%. The mean D-index was the same between the groups (0.93 ± 0.05 for ADH(-) and 0.93 ± 0.06 for ADH(+), p = 0.273). Among genders, 70% of the answers were from females (cis or trans), corresponding to the biological sex, with an estimated participation of <1% of transgender people. The distribution of ASRS scores (Figure 1A) is normal (p <0.0001, Shapiro-Wilk test) with 70.96% of scores between 1.00 and 2.50, (mean 1.70 ± 0.68 std, and median of 1.66). The average age of participants was 40.30 ± 12.18 years, with normal distribution (p <0.0001, Figure 1B). Only 4% of participants reported having technical courses as the highest level of education. Therefore, we disregarded it in subsequent analyses. Incomes and schooling distributions were non-normal (Figure 1C and D).

About self-perception of psychological problems, 91 subjects (4.23%) stated they were ADHD (80 ADH(+) subjects by ASRS). Correcting for equality of male and female individuals, we estimated a prevalence of 5.88%, being 7.22% and 2.95% of males and females, respectively.

The questionnaires from the 2126 selected subjects are described in terms of distributions of frequencies for (A) ASRS scores, (B) ages, (C) higher education level, and (D) financial (monthly) incomes. The classes in C are: no education (0), elementary school (1), incomplete high school (2), complete high school (3), technical degree (4), incomplete/attending graduation (5), complete graduation (6), post-graduation (7). Additionally, the classes in D are a scale of incomes with 11 levels ranging from R$ 1500.00 to “R$ 15,000.00 or more”.

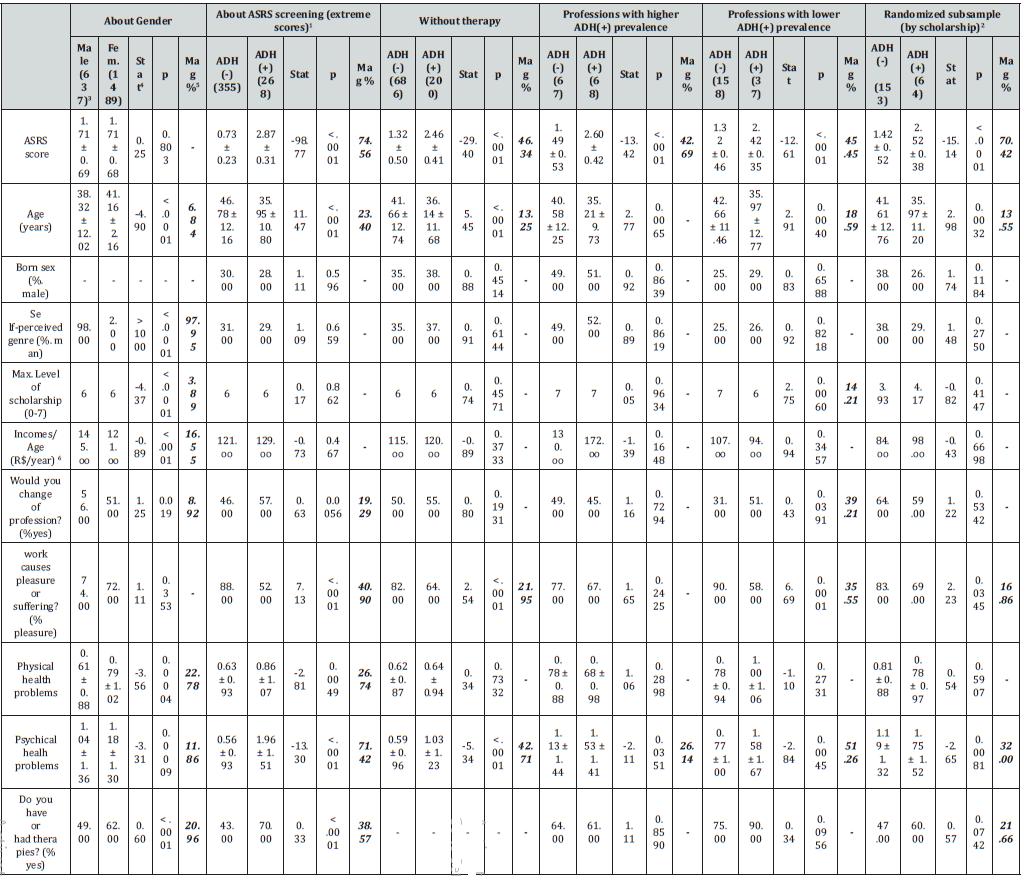

The effect of biological sex

The female sample is approximately 3 years older (p> 0.0001), with a statistically higher level of education by 5% (“undergraduate” class). Conversely, average female incomes are about 20% lower than those of males (p < 0.0001). Women reported more physical and psychical problems and they underwent more therapies than males. See Table 2.

Effect of ADHD phenomenology

The proportion of male/female and men/women in the groups formed by participants with extreme ASRS scores (ADH(-) <1.0, n = 355 and ADH(+)> 2.5, n = 268) was also 70% and 30% in both ADH(+) and ADH(-) groups (Table 2), respectively. ADH(+) and ADH(-) groups are statistically the same for rate incomes/age, schooling, and number of graduations (Table 2). Regarding work suffering, 88% of the ADH(-) group said that work is a pleasure, against 52% of the ADH(+) group (p < 0.0001, see Table 2). In this line, 46% and 57% people, from the ADH(-) and ADH(+) groups, respectively, would change their profession (p = 0.0056, Table 2). Subjects in the ADH(+) group observed more physical problems than those in the ADH(-) group (p = 0.0049). Mental problems are four times higher in the ADH(+) group (p < 0.0001, magnitude: 71.42%). In the ADH(+) group, 70% claimed to have already had therapy, compared to 43% of the ADH(-) group (p <0.0001).

Effect of therapeutic intervention on ADH

There are 200 and 686 subjects in the ADH(+) and ADH(-) groups, respectively, which remain statistically equal for income/ age, scholarship, and number of higher education courses. Still, these subjects did not show difference either in desire to change their professions or in the perception of physical diseases. However, psychic problems perceived by individuals in the ADH(+) group were also twice as large as the ADH(-) group (p < 0.0001), and the ADH(+) group suffered 18% more at work (p < 0.0001, Table 2).

Effect of professional settings on ADH

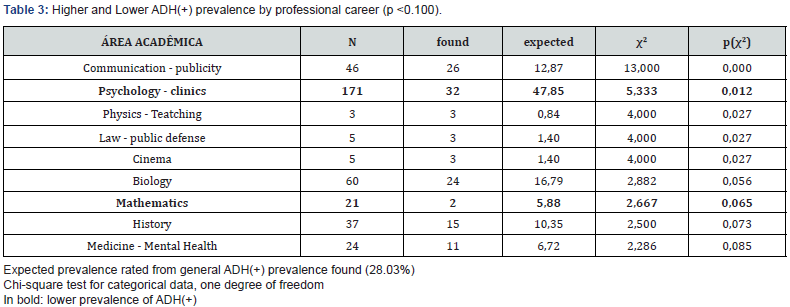

We found professions with both significantly higher and lower prevalence than that expected from ADH(+) subjects. The seven professions with the highest prevalence of ADH(+) (p <0.100) were: publicity (Found/Expected = 2.02, p = 0.0001), physics-degree (F/E = 3.57, p = 0.027), public defender (F/E = 2.14, p = 0.027), cinema (F/E = 2.14, p = 0.027), biology (F/E = 1.44, p = 0.056), history (F/E = 1.41 , p = 0.073), medicine-mental health(F/E = 1.63, p = 0.085). See Table 3.

These professions with high prevalence of ADH(+) totaled 68 ADH(+) and 67 ADH(-) subjects. Academic and economic performance also remained the same across groups (Table 2). When we evaluated subjective suffering, the groups were not different regarding occupational stress or self-perception of physical illness. However, there was also higher incidence of selfperception of psychic problems in the ADH(+) group (p = 0.0351), with a magnitude of 26.14%.

Two professions with the lowest prevalence of ADHD (p <0.100) were, in order of significance, clinical psychology (F/E = 0.66, p = 0.012) and mathematics (F/E = 0.34, p = 0.065), with a total of 31 ADH(+) and 158 ADH(-) subjects (Table 3). While income/age was not different once again, ADH(+) subjects had significantly lower education than ADH(-) (p = 0.0060), equivalent to “graduation” and “post-graduation”, respectively. Regarding subjective suffering related to work stress and self-perception of physical/mental problems, ADH(+) individuals would change their profession (p = 0.0391, magnitude: 39.21%), as they related it to suffering (42% in ADH(+), versus 10% in ADH(-), p = 0.0001, magnitude: 35.55%). As in general scenarios, ADH(+) individuals also had a higher perception of psychic problems (p = 0.0045, magnitude: 51.26%). See Table 2.

Effect of ADH phenomenology on randomized stratified subsample

The rarest class was “elementary school” (31 subjects). Thus, we stratified this subsample with 217 subjects (ADH(-) = 153, ADH(+) = 64). As observed in previous comparisons, there are no differences regarding incomes and scholarship, or desire to change professions (Table 2). Again, ADH(+) showed higher suffering related to work. Self-perception of clinical problems were the same between the groups, and ADH(+) mentioned more psychical problems. However, the magnitude was lower than in other scenarios (32.00%). See Table 2.

Discussion

Main characteristics of ADHD profile

The present study is a preliminary discussion about whether ADHD should be a mental disorder, according to the formal definition of DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), studying a general population without a priori diagnosis. If subjects with ADHD screening (+) show (1) academic and professional functionality [24] regarded as an important impairment on ADHD, (2) as well adaptability in specific settings, without any correlation with previous treatments, we can discuss the morbid nature of ADH as influenced by work/social stress. Despite the limitations of this study (which will be discussed later), we believe we have raised this debate with new insights. This study does not address subjects’ pathway into adulthood, although ADHD might manifest in childhood, but we assume that our findings are an outcome of individual history of psychosocial development.

Our core instrument to access ADHD was ASRS, a selfassessment recommended by the World Health Organization for ADHD screening. The six-question self-assessment questionnaire used here has a sensitivity of 68.7% and a specificity of 99.5% (equivalent to the 18-question version) and total classification accuracy of 97.9%, estimated regarding the DSM- IV [21]. These results show that the inventory of six questions is an ideal screening tool for research, with a very low false-positive rate. There are previous experiences using ASRS by phone or online surveys [28-32]. The reliability of answers was warranted by Cronbach’s index and ASRS re-testing amid distracting questions. The ASRS is a screening tool and we did not intend to establish ADHD diagnosis using it (so we were careful to mention ADH). Similarly, the questionnaire addresses demographic issues and people’s perceptions of themselves and their lives, without any value as (or any intention of being) a diagnostic or clinical assessment.

In our study, we analyzed the subjects in several scenarios, maximizing accuracy in ASRS screening for ADHD by selecting subjects with extreme scores, observing the effect of psychotherapy and professions with higher and lower ADH(+) prevalence. We also observed how consistent were the findings using a randomized sample stratified by schooling, which did not have an original distribution of frequency that was representative of the overall population. In nearly all scenarios (except for professions with lower ADH(+) prevalence), functionality in terms of academic and economic performance was statistically the same between people with (+) and (-) screening for ADHD. According to the ASRS screening in the universe studied, these findings are counterintuitive in light of our premises regarding ADHD. However, they clearly indicate that ADHD symptoms are not related with what has historically been established [18-19]. It does not seem to be a bias generated by the schooling profile of the sample, as the randomized/stratified scenario confirms the results. One explanation for our results might be that outcome studies that built a morbid profile for ADHD have been conducted with samples of institutionalized people with well-established mental disorders or with history of school problems, and not with the overall population through a blind study, with participants who are naïve regarding the objectives of the study. We have not identified previous studies with designs compatible with ours.

On the other hand, in almost all scenarios, the perception of psychic (and even physical) problems as well as the report of labor dissatisfaction, which would denote the ability of people to adapt to life stressors, was worse in ADH(+) people. However, in the setting of professions with higher ADH(+) prevalence, this phenomenon was substantially mitigated: there is no longer evidence of labor stress, of higher perception of clinical illness, nor of higher frequency of therapies undergone. Additionally, the magnitude of differences between groups regarding perception of psychic problems is the lowest among all scenarios. In this particular case, if we correct the p-value using the Bonferroni method, the difference is no longer significant (multiplying by six, the number of studied scenarios). On the other hand, in professional settings with lower ADH(+) prevalence, the ADH(+) group shows once again a pattern of higher suffering, and indirectly, lower schooling compared to the ADH(-) group. These results corroborate the idea that the disability clearly observed in the ADH(+) group would primarily result from the influence of socio-cultural stressors, in this case related to labor and its context of social relationships, which are a cardinal dimension of human life.

Publicity was the professional setting with the highest prevalence of ADH(+) people, with absolute significance in probability of difference between groups (p = 0.0001, or p = 0.0096, corrected by the Bonferroni method). It is obvious that cognitive work profile as well as organization of the environment and work relations in Publicity is quite different from teaching mathematics or exercising clinical psychology. ADH(+) people probably identify a higher compatibility between their personality and skill profiles and certain professional profiles, in which the morbid effects currently related with ADHD are significantly mitigated. As a parameter for a comparative discussion, we studied the differences between male and female genders in the same dimensions. With the historical knowledge that there are differences between genders regarding income in the Brazilian setting [32] and incidence of psychic suffering secondary to stress [33] although gender is not considerable as a morbid factor nor a disorder in itself, a qualitatively similar profile of differences was found between male and female genders and between ADH(+) and ADH(-) scenarios. Women manifested lower dissatisfaction with their profession; however, they showed higher perception of physical and psychic problems, and higher frequency in undergoing therapies. In accordance with national statistics, women showed a significantly lower economic performance, even having higher educational level (this finding is an indicator of quality in our data). Similar to being a woman, having ADHD profile might be understood as a risk factor for illness due to social and cultural stress and due to stigmatization.

The inverse relationship between age and ASRS scores was one of the most typical results, in any of the five studied scenarios. This relationship is more evident in the ADH(-) group and is not significant in the ADH(+) group, thus showing dimensionality between typical people. This result suggests that ADHD symptomatology might be related to a slower development of cognitive functions [9,34,35]. Finally, another issue observed was the great prevalence of ADH(+) people regarding current epidemiological studies [36,37], which was 28.03%. The first thing that comes to mind is related to ASRS quality, as well as the method of application. However, a possible explanation for this is related to the nature of the recruitment of participants in this study, which shall be discussed below.

Methodological considerations and limitations

One evident limitation of this study was the non-randomization of subjects during recruitment. An on-demand sample is subject to several biases, which are identified through distributions of frequencies not compatible with the original population. As we recruited 2126 subjects, we were able to perform a subsampling with randomization and stratification by schooling level, which mitigated the sampling bias in the inference of results about functionality and adaptability in the overall population. The 28% prevalence of ADHD found here might have resulted from the on-demand sampling, related to the public title of the survey (“Relationship between Behavior, Health, and Working Life”), which is more striking for people who experience problems or suffering at work and in overall health. However, since we have a strict report of ASRS scores, as this is a validated instrument, and our inference derived from a randomized/stratified subsample, we can assume that there was no impact on the quality of the results. Overall, the ADHD prevalence observed in several studies has varied greatly [36,38-40], reaching 16.4% in a survey over the phone using DSM-IV criteria [29]. Even though ADHD is a global perception [41], its estimated prevalence fluctuates too much between different regions in the world in studies that use the same diagnostic guidelines [37], which should be seen as evidence of a nosological inconsistency.

Conclusion

Indeed, ADHD is biologically a well-defined entity, probably related to slower maturation of the prefrontal cortex with impaired selective and sustained attention and behavioral inhibition [9,34] associated to the right hemisphere prevalence [42,43,10].

These features could explain on the one hand the limitations of executive functions as well verbal and analytical abilities (cardinal for psychology and mathematics) but maybe, on the other hand, a higher expressiveness of creative and imagery skills (necessary for Publicity). In this line, we have found evidence for feed the discussion whether Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity “profile” is primarily a mental disorder at all: evaluating a naïve sample, as well several subsamples from it, (1) there does not seem to be a statistical correlation between symptom an dysfunction; and (2) perceptions related to maladaptation also vanished in preferred professional settings. Thus, our findings in this preliminary study point to an alternative interpretation of attention deficit and hyperactivity phenomenology as a different cognitive style manifesting mental suffering and disorder influenced by social stress. Future researchers that clinically explores specific groups of successful people with an ADHD profile will be valuable in an attempt to elucidate the issues raised here.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and Faculdade Arthur Sá Earp Neto for supporting this research, and also to all people who participated in the project. They also thank to Mrs C. Fernandes for implementing the questionnaire in Google Forms. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

i. Questionnaire: Online form. The form was implemented in the Google Forms platform.

ii. Dataset. Collected data. In the first sheet, data organized by kind of variable. Binary and categorical scalar data were converted in numerical correlates (see methods). Second sheet, ASRS output and retest (five questions in respective order of appearance)

Statements

Conflict of interest: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability: Raw data are available on repository as mentioned in the text.

Funding: This work was developed without any funding support.

References

- Wakefield JC (1992) The concept of mental disorder: On the boundary between biological facts and social values. American Psychologist 47: 373-388.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Washington, DC, USA.

- Szasz TS (1960) The myth of mental illness. American Psychologist 15: 113-118.

- Miller R (2014) Validating concepts of mental disorder: precedents from the history of science. Biological Cybernetics 108: 689-699.

- Peixoto PTC (2016) Compositions Affectives, Ville &HétérogénèseUrbaine: Pour uneDémocratieCompositionnelle. Paulo de TarsoEdições, Macaé, Brazil.

- Masuch TV, Bea M, Alm B, Deibler P, Sobanski E (2019) Internalized stigma, anticipated discrimination and perceived public stigma in adults with ADHD. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders 11: 211-220.

- Thornicroft G, Bakolis I, Evans-Lacko S, Gronholm PC, Henderson C, et al. (2019) Key lessons learned from the INDIGO global network on mental health related stigma and discrimination. World Psychiatry 18: 229-230.

- Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, et al. (2016) Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet 387: 1123-1132.

- Fassbender C, Schweitzer JB (2006) Is there evidence for neural compensation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? A review of the functional neuroimaging literature. Clinical Psychology Reviews 26: 445-465.

- Abramov DM, Cunha CQ, Galhanone PR, Alvim RJ, et al. (2019a) Neurophysiological and behavioral correlates of alertness impairment and compensatory processes in ADHD evidenced by the Attention Network Test. PloS ONE 14: e0219472.

- Abramov DM, Lazarev VV, Mourao-Junior CA, Junior SCG, Pontes MC, et al. (2019b) Estimating biological accuracy of DSM for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on multivariate analysis for small samples. PeerJ 7: e7074.

- Wermter AK, Laucht M, Schimmelmann BG, Banaschewski T, SonugaBarke EJ, et al. (2010) From nature versus nurture, via nature and nurture, to gene× environment interaction in mental disorders. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 19: 199-210.

- Hooft MN, Denis C, Pitchot W (2016) Controversies around the diagnosis of ADHD. La Revue Médicale de Liège 71: 141-146.

- Strauss V (2012) An ADHD controversy in the mental health community. The Washington Post.

- Asherson P, Akehurst R, Kooij JJS, Huss M, Beusterien K, et al. (2012) Under Diagnosis of Adult ADHD: Cultural Influences and Societal Burden. Journal of Attention Disorders 16: 20S–38S.

- Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Young S, Kahle J, et al. (2012) A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Medicine 10: e99.

- Molina BSG, Pelham Jr WE (2014) Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Risk of Substance Use Disorder: Developmental Considerations, Potential Pathways, and Opportunities for Research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 10: 607–639.

- Goodman DW (2007) The consequences of Attention-Defict/Hiperactivity Disorder in Adults. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 13: 318-327.

- Polderman TJC, Boomsma DI, Bartels M, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC (2010) A systematic review of prospective studies on attention problems and academic achievement. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 122: 271–284.

- World Health Organization (2004) Escala para Auto-Avaliação do Transtorno do Défict de Atenção/Hiperatividade do AdultoVersão 1.1 (ASRS V1.1).

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, et al. (2005) The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): A Short Screening Scale for Use in the General Population. Psychological Medicine 35: 245-256.

- Mattos P, Segenreich D, Saboya E, Louzã M, Dias G, et al. (2006) Adaptação transcultural para o português da escala Adult Self-Report Scale para avaliação do transtorno de déficit de atenção/hiperatividade (TDAH) emadultos. Revista de PsiquiatriaClínica 33: 188-194.

- Hines JL, King TS, Curry WJ (2012) The adult ADHD self-report scale for screening for adult attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 25: 847-853.

- World Health Organization (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. World Health Organization, Geneva,Europe.

- Cortina JM (1993) What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 98-104.

- Tavakol M, Dennick R (2011) Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. International Journal of Medical Education 2: 53–55.

- Cohen JA (1992) Power primer. Psychology Bulletin 112: 155-159.

- Gray S, Woltering S, Mawjee K, Tannock R (2014) The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): utility in college students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. PeerJ 2: e324.

- Faraone SV, Biederman J (2015) What is the prevalence of adult ADHD? Results of a population screen of 966 adults. Journal of Attention Disorders 9: 384-391.

- Panagiotidi M, Overton PG, Stafford T (2019) Co-Occurrence of ASD and ADHD Traits in an Adult Population. Journal of Attention Disorders 23: 1407-1415.

- Wernicke J, Li M, Sha P, Zhou M, Sindermann C, et al. (2019) Individual differences in tendencies to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and emotionality: empirical evidence in young healthy adults from Germany and China. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders 11: 167-182.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2019) SériesHistóricas - 2019. Códigos PE347 e FDT301.

- Yehuda R, Hoge CW, McFarlane AC, Vermetten E, Lanius RA, et al. (2015) Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 1: 15057.

- Fassbender C, Schweitzer JB, Cortes CR, Tagamets MA, Windsor TA, et al. (2011) Working memory in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a lack of specialization of brain function. PLoS ONE 6: e27240.

- Marcos-Vidal L, Martínez-García M, Pretus C, Garcia Garcia D, Martínez K, et al. (2018) Local functional connectivity suggests functional immaturity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Human Brain Mapping 39: 2442-2454.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, et al. (2006) The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry 163: 716–723.

- Polanczyk G, Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA (2007) The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 164: 943-948.

- Garnier Dykstra LM, Pinchevsky GM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, et al. (2010) Self-reported adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms among college students. Journal of American College Health 59: 133-136.

- Polanczyk G, Laranjeira R, Zaleski M, Pinsky I, Caetano R, et al. (2010) ADHD in a representative sample of the Brazilian population: estimated prevalence and comparative adequacy of criteria between adolescents and adults according to the item response theory. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 19: 177-184.

- Syed H, Masaud TM, Nkire N, Iro C, Garland MR (2010) Estimating the prevalence of adult ADHD in the psychiatric clinic: a cross-sectional study using the adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS). The Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 27: 195-197.

- Bauermeister JJ, Canino G, Polanczyk G, Rohde LA (2010) ADHD across cultures: is there evidence for a bidimensional organization of symptoms? Jounal of Clinical Child Adolescent Psychology 39: 362-372.

- Mihov KM, Denzler M, Förster J (2010) Hemispheric specialization and creative thinking: a meta-analytic review of lateralization of creativity. Brain and Cognition 72: 442-444.

- Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, Proal E, Di Martino A, et al. (2012) Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. American Journal of Psychiatry 169: 1038-1055.