Mediating Role of Body Attitudes on the Relationship between Core Beliefs about Eating and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Turkish College Students

F Elif Ergüney Okumuş1* and H Özlem Sertel-Berk2

1Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University, Turkey

2Department of Psychology, Faculty of Letters, Istanbul University, Turkey

Submission: August 20, 2020;Published: September 22, 2020

*Corresponding author: F Elif Ergüney Okumuş, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University, Halkalı 34303 Küçükçekmece/Istanbul, Turkey This study is originated from first authors PhD thesis and it was presented in XVI European Congress of Psychology as an oral presentation.

How to cite this article:F Elif Ergüney O, H Özlem S-B. Mediating Role of Body Attitudes on the Relationship between Core Beliefs about Eating and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Turkish College Students. Psychol Behav Sci Int J .2020; 15(3): 55591410.19090/PBSIJ.2019.10.555914.

Abstract

College students are considered at-risk population for disordered eating behaviors and it is assumed that understanding the contributors of these behaviors can guide preventive studies. Thus, the aim of this study is to investigate the mediating role of body attitudes on the relationship between core beliefs and disordered eating behaviors in a college sample. The sample consisted of 729 students (200 male and 529 female) in various universities from six different cities in Turkey. A sociodemographic form, Body Image Questionnaire, Eating Disorders Belief Questionnaire, Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale were used. The results suggested that core beliefs had an effect on disordered eating behaviors via body attitudes partially, which show consistency with cognitive theories and previous studies. Hence, it is essential that the prevention programs should consider these risk factors.

Keywords:Eating behaviors; Body dissatisfaction; Core-beliefs; Eating disorders; Attitudes

Introduction

Disordered eating is defined as abnormal eating patterns like restricting, overeating and is also associated often with preoccupation about weight, shape and body which is not classified as a psychiatric disorder but is an important indicator of Eating Disorders (EDs) [1]. Since the transition to college is usually experienced as a stressful life event, recent research introduces this developmental stage as ‘emerging adulthood’ and focuses on the risk factors for preventive studies [2-4]. Along with other psychological problems, disordered eating behavior is also common in college students and put them on risk for developing EDs as well as other chronic illnesses that would cause serious health outcomes both in individual and economical terms [5-7]. EDs on the other hand are serious psychiatric disorders, which are usually accompanied by comorbid psychiatric and physical problems [8]. Lifetime prevalence of EDs are between %1-5 but subthreshold EDs are more common especially in risk groups [9,10]. Prominent types of EDs that usually begin through adolescent years are Anorexia Nervosa(AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN) and Binge Eating Disorders (BED) [1]. However, most of the cases fail to get a DSM diagnosis and usually fell into the not otherwise specified category that was EDNOS in DSM-IV and OSFED in DSM-5 [11,12]. The underlying psychopathology in EDs is an intense fear of gaining weight, and a pre-occupation with shape, body and eating that encourages compensatory behaviors like dieting, exercise, self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, etc. [13]. It has been long debated that EDs and related problems are more common in Western world since the thin idealization; nevertheless, growing research in non-western countries proves the other way [14,15]. While sociocultural factors can play an important role in the etiology of EDs, it is considered to have a multidimensional framework that includes biological, psychological and social explanations as well. Within this context, body image problems are an important indicator of EDs both in clinical and non-clinical population [16,17].

Body image is a multidimensional framework that includes attitudes, emotions, cognitions and behaviors related to body and an essential part of psychopathology and clinical intervention in EDs [18,19]. Body dissatisfaction in this manner, is conceptualized as the attitudes towards body and is quite prevalent in nonclinical samples especially in adolescents [20]. Most studies in this field concern how body dissatisfaction predicts disordered eating and excessive exercise. Previous researches consistently support that body dissatisfaction is one of the most serious risk factor of disordered eating [16,19]. However, recent studies suggested that the deterioration is in the underlying cognitive mechanism, that is beyond attitudes [21,22]. It was stated that core beliefs have a critical role and these belief systems are responsible for both in the development and progress of problems [23]. Core beliefs are central cognitive elements that were shaped with childhood experiences and solidified over time as they typically filter one’s perceptions of his/her experiences. So, people tend to store the information that is consisted with the maladaptive beliefs and ignore the opposite evidences. That makes core beliefs more rigid and they can easily be triggered by different situations. Dysfunctional core beliefs in EDs predominantly are concerned with weight, shape, self and control [24]. Cooper, et al. [25] suggested that four dominant dimensions are important in patients with EDs. Beliefs about weight and shape as a means of self-acceptance and acceptance by others are the most significant ones whereas control over eating is also common. Furthermore, people with eating problems are not only preoccupied with food and body but they also usually have negative self-image since they experience negative beliefs about themselves and this dimension is a predisposing factor. These different aspects of beliefs are reported to be related with disordered eating behaviors in patients with AN [26], BN and EDNOS [27], obesity and also nonclinical samples like college students [28].

Cognitive Behavioral Theory (CBT) in the forefront with evidence-based treatment studies [29] explains the etiology of EDs, as people exhibit disordered eating behaviors in order to have an ideal weight/body because of over-evaluation of their thoughts about weight and shape. CBT and its variations focus both on the etiology and treatment of EDs, nevertheless more research is needed to understand the nature of the problem since subthreshold symptoms are more common and even with the evidence-based interventions, full recovery is only limited with half of the patients [30]. On the other hand, studies from preventive health psychology perspective, aiming to identify risky eating behaviors and to promote healthy eating are also noteworthy. Predominant models of health behavior change such as Health Belief Model [31], Theory of Reasoned Action [32], Theory of Planned Behavior [33] and Integrated Behavioral Model [34] which assume that behavior is associated with belief and attitudes are also adapted to promote healthy eating behavior [35]. Preventive studies targeting college students, that originates from these models, have also emerged in this regard. The handicap of these studies is that we only know some of the risk factors but unfortunately, the etiology of EDs has not been fully understood yet. Hence, it is important to investigate the etiological models of EDs especially in these risky populations.

In sum, body dissatisfaction is an important indicator of disordered eating behavior as the level of dissatisfaction increase, the impairment in eating behavior also increases both in clinical and community samples [36,37]. Moreover, dysfunctional core beliefs are associated with disordered eating behaviors [27,28,38- 40]. For this reason, given the results of previous findings, the aim of this study is to evaluate the predictor effect of core beliefs on eating behavior and the mediating role of body dissatisfaction on the relationship between core beliefs and disordered eating behavior in college students. Large-scale studies targeting disordered eating behavior in risk groups are not common especially in Turkey and most of the research that focus risk factors of EDs is only limited with female participants. In addition, indicators of EDs might be different in nonwestern societies since sociocultural factors may have an effect on eating behavior as well. Hence, the findings of present study may contribute literature in these manners.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 1000 voluntary students from state and foundation universities in six different cities (Istanbul, Kocaeli, Usak, Bursa, Manisa and Giresun) in Turkey participated in the study. Students were informed that the purpose of the study was to understand college students’ eating behaviors and related factors. The study was ethically approved by the Istanbul University Ethical Committee in Social and Human Sciences. The students first were provided informed consent, and then were asked to complete the research battery during their course times. Among participants who failed to respond %95 of the questionnaires were excluded (n=271) due to missing answers, resulting in a final sample of 729. The sample included 529 (68.6%) women and 200 (31.4%) men. Most of the participants were in middle class (%77,8) and spent most of their life in the western regions of Turkey (%57,6). Mean age of the sample was 20,65 (SD=3.09).

Measures

Sociodemographic Form: Participants completed a sociodemographic form that includes questions about basic socio demographics (age, gender, economic status, body mass index) as well as the frequency of diet and exercise.

Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDEQ): This questionnaire developed by Cooper and Fairburn [41] from Eating Disorders Examination Interview was used to measure severity of disordered eating behaviors. This 28 item self-report questionnaire has five subscales that include Restraint of food intake (R), Binge Eating (BE), Eating Concerns (EC), Shape Concerns (SC) and Wight Concerns (WEC), sub-scale scores can be summed to a total score [42]. The item score range from 0 to 6, where a higher score implies more severe levels of eating disorder symptoms. The Turkish translation of the EDE-Q was found to have satisfactory reliability and validity [43].

Satisfaction of Body Parts and Their Features Questionnaire (SBPFQ): Body satisfaction of participants were examined with Satisfaction of Body Parts and Their Features Questionnaire (SBPFQ) that was developed by Gökdoğan (1998) and has its origins from Berscheid, Walster and Bohrnstedt’s [44] Body Image Questionnaire. It has 25 items for women and 26 for men in 4 dimensions (general appearance of the body, face, body parts, body). The item score ranges from 1 to 5, a total score is also available summing thorough the subscales, higher scores indicating higher levels of body satisfaction.

Eating Disorder Belief Questionnaire (EDBQ): Core Beliefs about eating were assessed through Eating Disorder Belief Questionnaire (EDBQ) by Cooper et al. [25]. It has 32 items, with four subscales as follows: negative self-beliefs, weight and shape as a means for acceptance by others; weight and shape as a means for self-acceptance, and control over eating. Items are rated on a scale from 0 to 100. Turkish adaptation of EDBQ was made by Karaköse [45] and reported to have good psychometric features. Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DAS): This scale was used to control psychopathology levels that could impact eating behaviors of participants. This scale is a set of three selfreport scales designed to measure negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress that developed by Lovibond & Lovibond [46]. It has 42 items and each item is scored from 0-3, higher scores indicate higher levels of negative emotions. The Turkish adaptation was made by Akın & Çetin [47].

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS (SPSS® version 21). Demographic data are reported in frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. Pearson correlation coefficient analysis was used to evaluate the relationships between the scales while linear regression analysis was used to determine the effects of the independent variables (subscales of EDBQ) on the dependent variable (EDE-Q total scores). Hierarchical linear mediator regression analyses was conducted for determining the mediating role of body attitudes (SBFQ total scores) on the relationships between eating core beliefs (EDBQ total and sub scores) and disordered eating behaviors (EDE-Q total score) while controlling gender differences and psychopathology level (DASS total scores). This analysis was performed according to the suggestions by Baron and Kenny (1986). In all statistical analyses, a p value of less than 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

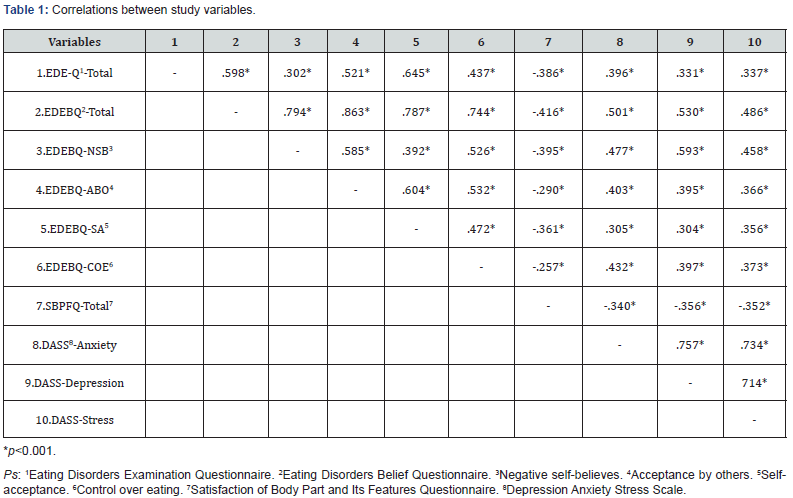

Table 1 shows the correlations between the study variables. Positive correlations were found between EDE-Q total score and EDBQ total score and all its subscales (negative self beliefs, acceptance by others, self-acceptance, control over eating) (r= 598, r=0.302, r=0.521, r=0.645, r=437, p<0.001, respectively). In terms of body satisfaction, as the level of satisfaction of one’s body decreases, the deterioration in eating behavior increases since SBPFQ was negatively correlated with EDE-Q total scores (r=-0.386, p<0.001). Lastly, the levels of anxiety, depression and stress levels of the participants according to DASS were found to be positively correlated with EDE-Q scores (r=0.396, r=0.331, r=0.337, p<0.001, respectively). In conclusion, all the study variables significantly correlated with each other in the expected direction.

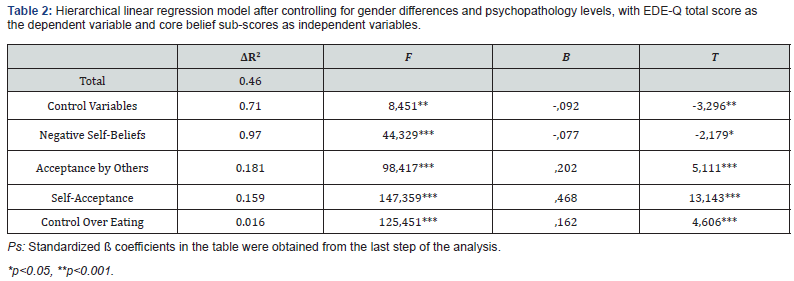

The hierarchical regression analysis showed that all the subscales of core beliefs together explained 46% of the EDE-Q total scores after controlling for gender differences and psychopathology levels. Table 2 shows that all the subscales of EDBQ significantly predicted disordered eating behavior scores. The prediction levels of different core beliefs from higher to lower were as self-acceptance, acceptance by others, control over eating and negative self-beliefs ( t=13.143, t=5.111, t=4.606, t=-2.179, p<0.001 respectively).

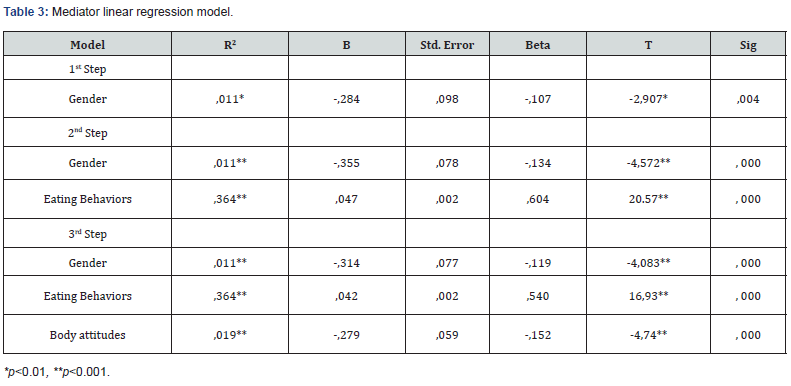

Linear mediator regression analyses resulted in a decrease of the predictor effect of core beliefs (EDBQ total scores) on disordered eating behaviors (EDEQ total scores) while controlling the mediator effect of body attitudes (SBFQ). As presented in Table 3, this decrease is significant according to Sobel test (Z= 4.573, p<0.001). Therefore, the effect of core beliefs on eating behaviors is partially mediated by body attitudes.

Discussion

College years have a significant effect through life that is also announced to be a stressful and a risky period especially for disordered eating behaviors. Preventive studies for EDs usually target etiological risk factors of EDs; hence, it is considered to be essential to understand the mechanism behind disordered eating in non-clinical samples. For this reason, the aim of the present study is to investigate the relations between core beliefs about eating, body attitudes and eating behavior and the mediating role of body attitudes on the relationship between core beliefs and eating behavior. The results indicate that as dysfunctional core beliefs and body dissatisfaction increase disordered eating behaviors increase, too. Previous researches also highlighted the link between these variables [48,49]. Thus, it can be concluded that dysfunctional core beliefs that are associated with eating, body and shape are important indicators of disordered eating behaviors in college students as consistent with the other studies in this field [25,28]. One of the assumptions of this study was that the sub dimensions of core beliefs that were assessed with eating disorders belief questionnaire [38] would differ in explaining disordered eating behaviors. According to the results of multiple hierarchical regression analyses ‘self-acceptance’ that is defined as one’s focusing merely his/her weight and shape as a means of self-acceptance was the best predictor of disordered eating behavior. Other dimensions of core beliefs, which are acceptance by others, control over eating and negative self-beliefs significantly predicted disordered eating. Although research in this area is limited, these results are consistent with Cooper and Turner’s [26] findings. It has been emphasized that the main psychopathology of EDs is preoccupation with weight, shape and body, which has its origins in dysfunctional beliefs that weight and shape are prominent factors in determining self-value, that can easily result in compensatory behaviors [13]. Our results also highlight the importance of these etiological explanations about EDs in a non-clinical sample. Fairburn’s [42] model explains EDs from CBT perspective as the underlying mechanism is dysfunctional core beliefs about weight, body and shape. Inflexible rules and assumptions that were created from core beliefs are thought to indicate disordered eating behaviors. From this point of view, attitudes about body are assumed to play a mediating role between dysfunctional core beliefs and eating behaviors since they are strongly associated with dysfunctional core beliefs [26,50,51] and disordered eating [52] in a number of previous studies.

A mediator regression analyses was conducted following Baron & Kenny’s [53] suggestions with EDE-Q total scores as the dependent variable and EDB-Q total scores as independent variable while controlling the mediator role of SBFQ total scores and gender as a control variable. Results indicated that body dissatisfaction has a partially mediating role between core beliefs and disordered eating. These findings suggest that core beliefs affect eating behaviors one way through body attitudes but also other variables that were not taken account by this study play a role in this relationship. Although this result suggests part of the relation between core beliefs and eating pathology can be a direct one, previous studies have also drawn attention on the role of not only eating attitudes [54], but also autonomy [55], emotion dysregulation [56], perfectionism and self-esteem [57] as risk factors for EDs. Hence the potential mediating effects of these variables are also subject for investigation in further studies. It has been long debated since the early research in EDs that positive body image is the key factor of complete remission [18]. On the other hand, both CBT model and health behavior models suggest that cognitive system affects behavior through attitudes that originate from beliefs [42,58]. In this manner, the results of the present study show consistency with these models as core beliefs form eating behaviors partially via negative body attitudes in a non-clinical sample after controlling gender differences. Hence, it is essential that the prevention programs for EDs in risky populations as college students should consider these risk factors [59-62].

This present study is the first study that focuses on the etiological factors of EDs with the largest sample that also include male college students in Turkey. However, it has its limitations as well. Firstly, the study is in cross-sectional design, which make it hard to generalize the findings or make causal attributions between variables. Another limitation is that the self-report scales used in this study could have produced biased or incorrect information. Moreover, the model of this study primarily focuses on the cognitive factors but it is well known that emotional factors may also play an important role in disordered eating behaviors. For this reason, future research that includes these factors and uses mixed models in longitudinal design can contribute to more sound inferences.

In conclusion, being aware of body dissatisfaction, disordered eating behaviors and the underlying cognitive factors may be important for community-based interventions that aim to prevent disordered eating in risky populations.

Declaration

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by Istanbul University Ethical Committee in Social and Human Sciences (No:2016/90).

Author Contribution

Conceptualization, F.E.E.O. and H.O.S.B.; Methodology, F.E.E.O. and H.O.S.B.; Formal Analysis, F.E.E.O. and H.O.S.B.; Investigation, F.E.E.O. and H.O.S.B; Resources, F.E.E.O. and H.O.S.B.; Writing- Original Draft Preparation, F.E.E.O.; Writing-Review & Editing, F.E.E.O. and H.O.S.B.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Pub.

- Arnett JJ (2000) Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychologist 55: 469-480.

- Ogden J (2011) The Psychology of Eating: From Healthy to Disordered Behavior. (2ndedn), John Wiley & Sons.

- Schulenberg JE, Zarrett NR (2007) Mental health during emerging adulthood: continuity and discontinuity in courses, causes, and functions. In: JJ Arnett JL, Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 135-172.

- Altun M, Kutlu Y (2015) The Views of Adolescent about The Eating Behaviour: A Qualitative Study. Florence Nightingale Journal of Nursing 23(3): 174-184.

- Levine MP, Smolak L (2018) Prevention of negative body image, disordered eating, and eating disorders: an update. Annual review of eating disorders, CRC Press, United States, pp.1-14.

- Lipson SK, Sonneville KR (2014) Eating disorder symptoms among undergraduate and graduate students at 12 US colleges and universities. Eating behaviors 24: 81-88.

- Herzog DB, Eddy KT (2018) Comorbidity in eating disorders. In: Annual Review of Eating Disorders. CRC Press, United States, pp. 35-50.

- Rahkonen AK, Mustelin L (2016) Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Current opinion in psychiatry 29: 340-345.

- Vardar E, Erzengin M (2011) The prevalence of eating disorders (EDs) and comorbid psychiatric disorders in adolescents: a two-stage community-based study. Turkish journal of psychiatry 22: 1-7.

- Smink FR, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW (2012) Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current psychiatry reports 14: 406-414.

- Smink FR, Van Hoeken D, Oldehinkel AJ, Hoek HW (2014) Prevalence and severity of DSM‐5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders 47: 610-619.

- Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press, United States.

- Hoek HW (2016) Review of the worldwide epidemiology of eating disorders. Current opinion in psychiatry 29: 336-339.

- Pike KM, Dunne PE (2015) The rise of eating disorders in Asia: a review. Journal of eating disorders 3: 33.

- Garner DM (2002) Body Image and Anorexia Nervosa. In: Cash TF, Prozinsky T (Eds.), Body Image: A handbook of Theory, Research and Practice. Guilford Press, New York, United States.

- Polivy J, Herman CP (2002) Causes of eating disorders. Annual review of psychology 53: 187-213.

- Bruch H (1962) Perceptual and conceptual disturbances in anorexia nervosa. Psychosomatic medicine 24: 187-194.

- Stice E (2002) Risk and Maintenance Factors for Eating Pathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin 128: 825-848.

- Grogan S (2016) Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. Routledge, United Kingdom.

- Ford G, Waller G, Mountford V (2011) Invalidating childhood environments and core beliefs in women with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review 19: 316-321.

- Rose KS, Cooper MJ, Turner H (2006) The eating disorder belief questionnaire: Psychometric properties in an adolescent sample. Eating behaviors 7: 410-418.

- Jones CJ, Leung N, Harris G (2007) Dysfunctional Core Beliefs in Eating Disorders: A Review. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy 21: 156-171.

- Cooper M, Todd A, Wells A (2004) Cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 43: 1-16.

- Cooper M, Cohen-Tovée E, Todd G, Wells A, Tovée M (1997) The eating disorder belief questionnaire: Preliminary development. Behaviour Research and Therapy 35: 381-388.

- Cooper M, Turner H (2000) Underlying assumptions and core beliefs in anorexia nervosa and dieting. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 39: 215-218.

- Hughes ML, Hamill M, van Gerko K, Lockwood R, Waller G (2006) The relationship between different levels of cognition and behavioural symptoms in the eating disorders. Eating behaviors 7: 125-133.

- Rawal A, Park RJ, Williams JMG (2010) Rumination, experiential avoidance, and dysfunctional thinking in eating disorders. Behavior Research and Therapy 48: 851-859.

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour research and therapy 41: 509-528.

- Cooper M, Rose KS, Turner H (2005) Core beliefs and the presence or absence of eating disorder symptoms and depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders 38: 60-64.

- Hochbaum G, Rosenstock I, Kegels S (1952) Health belief model. United States Public Health Service, W432W8784.

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, Mass.: Addison Wessley, United States.

- Ajzen I (1985) From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Action control. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, pp.11-39.

- Montano DE, Kasprzyk D (2015) Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health behavior: Theory, research and practice, pp. 95-124.

- De Bruijn GJ (2010) Understanding college students’ fruit consumption. Integrating habit strength in the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 54: 16-22.

- Kadriu F, Kelpi M, Kalyva E (2014) Eating-disordered behaviours in Kosovo school-based population: potential risk factors. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 114: 382-387.

- Nerini A, Matera C, Stefanile C (2016) Siblings’ appearance-related commentary, body dissatisfaction, and risky eating behaviors in young women. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée/European Review of Applied Psychology 66: 269-276.

- Cooper M (1997) Cognitive theory in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A review. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 25: 113-145.

- Davenport E, Rushford N, Soon S, McDermott C (2015) Dysfunctional metacognition and drive for thinness in typical and atypical anorexia nervosa. Journal of eating disorders 3: 1-24.

- Cooper M, Todd G, Wells A (2008) Treating bulimia nervosa and binge eating: An integrated metacognitive and cognitive therapy manual. Routledge, United Kingdom.

- Cooper Z, Fairburn C (1987) The eating disorder examination: A semi‐structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. International journal of eating disorders 6: 1-8.

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (2008) Eating disorder examination questionnaire. Cognitive behaviour therapy and eating disorders. pp. 309-313.

- Yucel B, Polat A, Ikiz T, Dusgor BP, Elif Yavuz A, et al. (2011) The Turkish version of the eating disorder examination questionnaire: reliability and validity in adolescents. European Eating Disorders Review 19: 509-511.

- Berscheid E, Walster E, Bohrnstedt G (1987) The happy American body: A survey report.

- Karaköse S (2012) The role of coping strategies and negative beliefs in predicting eating disorder symptomatology. Unpublished master’s thesis, Maltepe University, Turkey.

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy 33: 335-343.

- Akin A, Çetin B (2007) The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS): The study of Validity and Reliability. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 7: 260-268.

- Ergüney-Okumuş FE, Sertel Berk, HÖ, & Yücel B (2016) Predictors of Treatment Motivation in Eating Disorders. Psikoloji Çalışmaları/Studies in Psychology 36: 41-64.

- Hawkins N, Richards PS, Granley HM, Stein DM (2004) The impact of exposure to the thin-ideal media image on women. Eating disorders 12: 35-50.

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Cooper PJ (1986) The clinical features and maintenance of bulimia nervosa. Handbook of eating disorders: Physiology, psychology and treatment of obesity, anorexia and bulimia, pp.389-404.

- Kluck AS (2010) Family influence on disordered eating: The role of body image dissatisfaction. Body image 7: 8-14.

- Wyssen A, Bryjova J, Meyer AH, Munsch S (2016) A model of disturbed eating behavior in men: The role of body dissatisfaction, emotion dysregulation and cognitive distortions. Psychiatry research 246: 9-15.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of personality and social psychology 51: 1173-1182.

- Okumuş FEE (2017) The Predictor Effects of Attitudes, Beliefs and Metacognitions on Eating Behavior. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Psychology Department, Istanbul University, Turkey.

- Narduzzi KJ, Jackson T (2002) Sociotropy-dependency and autonomy as predictors of eating disturbance among Canadian female college students. The Journal of genetic psychology 163: 389-401.

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Peat CM, Claes L, Smits D (2012) Self‐injury and disordered eating: Expressing emotion dysregulation through the body. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior 42: 416-425.

- Bardone-Cone AM, Lin SL, Butler RM (2017) Perfectionism and contingent self-worth in relation to disordered eating and anxiety. Behavior therapy 48: 380-390.

- Beck JS (2011) Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford press (2ndedn), ISBN: 978-1-60918-504-6.

- Cooper M (2003) The psychology of bulimia nervosa: a cognitive perspective. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Gökdoğan F (1988) The level of body image satisfaction in secondary school students. Unpublished master’s thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey.

- IBM Corp (2012) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States.

- PoveyR, Conner M, Sparks P, James R, Shepherd R (2000) Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to two dietary behaviours: Roles of perceived control and self‐efficacy. British Journal of Health Psychology 5: 121-139.