Distortion of the Perception of Existential Space: as Illustrated by Phobias

Aharoni Avi* and Professor Izhak Schnell

Department of Geography, Tel-Aviv University, Israel

Submission: June 08, 2020;Published: September 17, 2020

*Corresponding author: Aharoni Avi, Department of Geography, Tel-Aviv University, Israel

How to cite this article:Aharoni A, Professor I S. Distortion of the Perception of Existential Space: as Illustrated by Phobias. Psychol Behav Sci Int J .2020; 15(3): 555913. DOI:10.19090/PBSIJ.2019.10.555913.

Abstract

The current study uses the phenomenological method and is concerned with phobic experiences and the distortion of fields and borders in the existential space, as a result of the distortion of the perceptual space, among individuals who suffer from phobic disorders. The school of psychology tends to define the phobic phenomenon as a sort of irrational anxiety. Therefore, it does not attribute any importance to the causes of the anxiety, as experienced by individuals suffering from phobia disorders. Furthermore, the field of psychology also tends to ignore the dominant role of the spatial factor. When anxieties are perceived in the existential space, they are transferred to the outer world; at the same time, in the existential space, a distortion occurs, which then becomes a real and tangible threat to the individuals who are experiencing the phobia. This experience imposes a meaningful and significant limitation on the “I” in the individual’s daily reality, and also harms the functioning ability of the individual suffering from phobic disorders (harm to the consciousness and its associated elements).

Keywords:Existential space; Spatial phobias; Field distortion; Border distortion

Introduction

The school of psychology tends to define the phenomenon of phobias as irrational anxieties. Therefore, it doesn’t ascribe importance to the causes of phobias, as they are experienced by phobic individuals. The discussion in particular ignores the relevance of the spatial experience in understanding how to decrease part of the phobias that have been diagnosed by psychologists. Expanding the concept of “space” in geographic terms allows us to focus on a study of the existential space. The definition of space – as the meeting point of interaction between the experiencing individual and the objects of the experience in the outer world – nullifies the dichotomy between the objective space, which describes the outer world, and the subjective space of human perception. This space may create an opening toward understanding reality, as it is experienced by individuals who suffer from phobia attacks, and raises the following question: Does the undermining of the stability of the existential space, as the primary link between man and his existence in the world, play a role in the phobic experience?

This discussion creates an opening for a collaborative effort between psychology and geography. Along the lines of Merleau- Ponty’s [1] proposal, we can hypothesize that studying and understanding the disruptions in the building of existential space may teach us about the importance of an individual’s success in creating his own stable, controllable existential space, which enables him to function within the reality of his daily life. Furthermore, we propose that failure to do so is one of the phenomena that defines a series of phobic phenomena. Against this background, certain questions arise, such as: Does a disruption of the existential space in phobic experiences occur in all or only some phobic experiences? Can we explain which types of phobic experiences lead to distortion of the existential space?

Hence, the aim of the current study is to examine to what extent space is a factor in understanding phobic phenomenon, and how space is distorted during phobic experiences. Moreover, the study also focuses on conceptualizing the neo-Kantian claim that man has an active role in applying spatial forms onto the personal reality he establishes in his daily life; conversely, distortion of this process does not allow him to lead a regular and routine life. In the current study, we will attempt to examine individuals who suffer from phobias and, who as a result, encounter difficulties defining their existential space and borders. People’s consciousness about their personal situational reality results from extreme events; through these extreme events, we can, as human beings, learn about people’s perceptions of their “supposedly normal” daily existential space. In our study, we chose to address phobias because phobias represent exaggerated, ongoing fears of a specific object or situation, which, in reality, represent little or no real danger to the individual in DSM-IV. In the professional literature, three types of basic phobias are described: specific phobias (phobias that belong to one specific area), social phobias, and agoraphobia (the fear of open spaces) – previously this phobia was defined in somewhat paradoxical terms as the fear of both open and enclosed spaces. However, today it is understood that agoraphobia, for most individuals, stems from the fear of panic attacks, where escape is considered to be difficult or embarrassing. This perspective balances out the paradox in that it may be perceived as difficult to escape from both open and enclosed spaces. Likewise, today, a close link is not recognized between agoraphobia and specific phobias. There is a wide range of common phobias and these give us an idea of the range of situations and events around which specific phobias may occur. In the current study, we will see that it is possible to relate to agoraphobia and several types of specific phobias as a group of diagnosed or recognized phobias defined as spatial phobias. In the current study, we chose three phobias that show the importance of one’s ability to create a stable existential space: acrophobia - fear of heights; claustrophobia (fear of enclosed spaces); and agoraphobia – fear of open spaces.

The article first discusses what may be learned from the psychological-geographical dialog existing on the subject. This comes as an introduction to examining phobic events. After that, a review of phobic events leads to the discussion of a general model of spatial phobias and its distinctiveness as regards other related experiences linked to phobic events. The Psychological Aspect Phobias are ongoing, constant fears from a specific object or event, which in reality; pose little or no real threat to the individual. Specific phobias may involve fears connected with certain types of animals (a fear of snakes and scorpions are the most common), or fear of different aspects of the external environment, such as fear of water or heights. A specific phobia is diagnosed when an individual responds with “a clear and constant fear, which is extreme or illogical and which appears after the appearance of a specific object or situation or the expectation of its appearance”, and when “exposure to a stimulus that arouses the phobia almost always causes an immediate response of anxiety”. Phobias, then, are similar in nature to panic attacks in every way, except that in the case of phobias, there is a clear external factor that brings on the anxiety or fear (DSM-IV, p. 410). Any attempt to avoid the fearful situation itself - or the crisis brought on by the fearful situation - has a significant disruptive influence on the individual’s regular functioning. There is a long list of common phobias, which gives us an idea of the range of situations and events around which specific phobias may occur. Specific phobias are indeed widespread, particularly among women. The findings of an epidemiological study conducted in the early 1980s showed a life-long distribution rate of phobias among more than 14% of women and almost 8% among men, Reiger and Robins (1991).

The ratio between male and female distribution rates differs significantly in accordance with the type of specific phobia. For example, 95% of the people who suffer from animal phobias are women, but as regards blood-wound phobias among genders, the ratio is less than 2:1. In addition, as regards the average age when the specific phobia appears, the variance is very different. Social phobias involve social situations where individuals are exposed to the scrutiny of others; in such situations these individuals fear humiliation and embarrassment. Social phobias may be defined (such as fear of public speaking) or general (such as fear of various types of inter-group social activities). Social phobias are very common, and an approximate estimation is that 2% of the entire population suffers from this type of phobia during every six-month period. Unlike specific phobias that usually appear during childhood and are more common among women, social phobias usually appear during adolescence or the beginning of adulthood and affect women and men equally.

Panic attacks are defined and characterized as the appearance of “unexpected” attacks of panic, which, often seem to occur for no special reason. According to the definition of the DSM-IV, an individual diagnosed as having experienced panic attacks has, during at least a one-month timeframe sudden, repeated and unexpected attacks, and is constantly concerned about either when the next attack will occur or the results of the attack itself (i.e., “losing control” or “going crazy”). As was explained previously, agoraphobia is connected to fear of the “agora”, the Greek word for a public gathering place, Marks (1987). Hence, agoraphobic individuals are most afraid - and wish to avoid - being out in the street or in crowded places such as malls, movie theatres and stadiums. Standing in a long line may be especially difficult. Together with this, agoraphobic individuals also tend to fear one or more modes of transportation, and many avoid traveling by car, bus, plane or subway. Agoraphobia is a common complication related to panic disturbances, but it may also occur on its own, with the absence of any previous full-fledged panic attack. In this case, the most common pattern is a gradual, escalating fear that continues to grow, where more and more places and spaces outside the home take on a threatening and frightening aspect. The age in which panic disturbances, with or without agoraphobia, appear is usually in the early 20s, although they sometimes occur toward the end of adolescence or in the 30s. From the moment the disturbance appears, it tends to become a chronic problem, although the level of intensity may fluctuate over time, Maser and Ehlers (1994) Wolfe (1995).

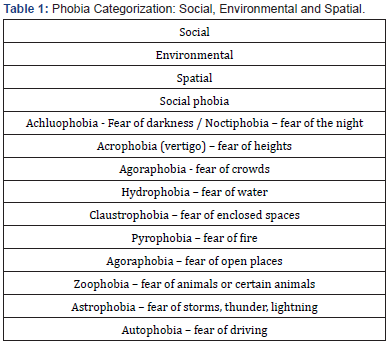

The psychological discussion focuses on the internal factors of the phobic experience, while ignoring the external factors. The developmental stages of a baby, both at birth and throughout childhood, co-exist together along a continuum of the external and internal factors that threaten him/her. The dichotomy between the external world and the internal world is dialectic in nature; as regards phobias, psychologists don’t relate to external factors in a serious manner. And in fact, just as internal factors play a significant and important role in the phobic experience, so too do external factors, such as the element of space (heights, open spaces, enclosed spaces) play a significant and recognized role in the phobic experience. Along the lines of Merleau-Ponty [1], a dialectic relationship exists between the individual and his environment. This relationship does not characterize a physical world and a human consciousness that are separate from one another, but rather a constant link between the two. The problematic nature of the psychological discussion raises the possibility to propose a different categorization of phobias. The current categorization, for the most part, consists of different content worlds based on levels of anxiety, the factors that stimulate the phobic phenomenon, or the level of specificity of the situations that cause phobic responses. I propose a categorization based on the dimension that relates to the external source of the phobia, which differentiates between social factors like fear of crowds; environmental factors like thunder, lightning, and water; and spatial factors like heights, enclosed spaces, and open spaces. In this way, and according to this method, each phobia may be categorized into three categories, as is presented in Table 1 below:

The Geographic Aspect Existential Space Common to all spatial phobias is the experiential distortions of the individual’s existential space during panic attacks, an unreported phenomenon during non-spatial phobic events, which is reported during spatial phobic attacks. The basic elements of existential space are as follows: field, border, focus, and bridge. A long list of neo-Kantian scholars’ ideas, including those of Cassirer, Cooper, Jung, Eliade and Bolnow, among others, present Man as creating symbols when he is confronted with phenomena [2-5]. People mark the environment within which they live by their daily actions and divide the world into meaningful spaces. This division of the world into “sacred spaces” and “unsacred spaces” is a basic element of these approaches. The existential space consists of parallel spaces. These are the individual’s existential spheres in the world, in other words, the tangible, physical, social and cultural dimensions. These spaces are created in a topological manner. The idea is that for every cultural change, accompanied by a change of place or space, a principle is at work, which we will term “the principle of separation and transference”.

Topological qualities such as separation, connectedness, continuity, adaptability, and consecutiveness are hidden forces that operate within this process and enable a continuity of emotional content. For every phenomenon of culturalgeographical projection, the following mechanism operates: After realization of the fact of separation between the previous situation and the new situation occurs, complex connections between the two situations still exist. The basic characteristic of the topological space is the ability to make connections between the tangible space and the other spaces, and to integrate them. The significance of the topological space rests upon the fact that its principles and characteristics are useful when examining different conceptual systems – both the internal world and the physical world or the facts relating to the temporary spatial experience. These topological characteristics are the internal principles that will serve as the meaningful and logical base of the existential space. Within the existential space, other existential spheres are constructed: the first sphere is the sphere of physical space, which is built from the same basic components as the existential space – the physical space is the space that is ‘closest’ to the individual. This is the space of physical things or objects, which we experience, before anything else, through our senses. The physical space is built from the same basic components as the existential space: field, border, focus and bridge. These components are expressed in a way that differs from every other existential sphere. In the abstract sphere, the same concepts are expressed as geometric objects, which exist as structures and simply represent the structures themselves - the focus is a point, the field is a polygon, the area, by use of a line, represents the bridge - represented by a line that connects two different polygons - while the border is represented by a line that separates the fields. In the cultural, social or personal spheres these objects do not exist, but are rather objects of conception, objects that are translated into a personal conceptual system in different ways. A focal point, for example, is represented as a place or focus of attention on its personal, social or cultural significance; the field translates to an environment created around a place; the border translates to a subjective description of the details that define the line separating the two different spaces; and finally, the bridge is a collection of objects or places, whose origin is based on the perception of the subject, and their ability to bridge between the different areas and/or times. An additional sphere is the emotional sphere, wherein the idea of the feeling of domesticity is formed. The feeling of domesticity stands at the center of this emotional sphere and is dependent upon the two most basic feelings: the feeling of belongingness or identity, and one’s sense of security. This is the world of our feelings and experiences and it is a central space.

The next sphere is the social space, comprised of three levels: the familial level, the community level, and the level of the masses or the nation. These three levels are reflected within the system of places with the symbolic meaning and its tangible existence in the existential world. The last sphere of existential space is the cultural space. This is a symbolic existential space and the historical database of the individual’s personal and social language, as it is represented within the symbolic patterns created by humanity. The cultural space is represented by myths, beliefs, science, religion, history and language. All of these components are translated at the personal-autobiographical level and are expressed by space and time. In addition, the mechanism of the topological space, and within it the continuity of all the parts of existential spheres, are necessary for the individual’s mental wholeness. The mechanism managed by the “separation and transference” principle is the process the individual experiences during cultural transitions and changes in destiny, a process that is realized simultaneously in every possible sphere of existence, Goldenberg (2000).

Borders

Borders define space and provide a relational framework. A lack of borders signifies, and is connected with, the need or desire to create them. Borders in the existential space are flexible – they become closed in certain situations and open up or disappear in other situations, whether through the experiencing individual’s initiative or via the initiative of elements from the external world. The possibility that inter-relational borders may disappear during certain periods may be especially meaningful and fulfil an important function, since there exists a connection of mutual dependence among different parts of space. The most central concept in Klein’s studies is that of anxiety. Anxiety is described as the central response of the “I”, mainly as it refers to internal events; however, also as it refers to external events, related to the struggle between the life force and the death force and to the nature of relationships with internal objects. Any contact with reality is always accompanied by anxiety, however, this anxiety is problematic, as it does not allow us to live well and take full advantage of our reality. Klein explains this by saying that every relationship we enjoy with the external world is based on the dialectic of internalization and projection and renewed internalization and renewed projection. The pressures in the birth canal, the sudden transition from the womb to the struggle for life outside of it, the shock of having to become a small and helpless “I” and leave the pantheistic pre-oral reality, the tearing away of the nurturing breast and the warm omnipotent mother who provides all to the narcissistic “I” - all of these events are incredibly painful for the unconscious baby, who can just barely cope with these crushing difficulties. Hence, these excruciating shocks of separation become part of the individual’s personal core of identity, these difficulties are a primary source of understanding as regards the hardships experienced during our first years of life, often filled with fears, anxieties, and painful relationships, as they are connected with expulsion and the end of the paradisiacal, preoral pantheistic period [6]. Conflicts that arise, which the baby cannot cope with, lead to the creation of a very strong ego border, which serves as a separation ‘wall’ between the baby and the external world. Hidden, extreme maternal messages, which the baby unconsciously perceives, create conflicts between the self and the maternal object. These messages result in the creation of a very strong ego border (paranoia), which makes the “self” relatively immune to the hidden messages absorbed by reality, and allows for the development of a negative attitude towards everything existing outside of the ego [6].

Winnicott maintains that the place we are in when we live our lives is not the internal world; the raw material it is comprised of consists of unconscious fantasies. Furthermore, this is not the realistic world, which we can either internalize or project upon. When we live our lives, explains Winnicott, we are first and foremost, in a transitional space – an area of potential space. The quality of the potential space is determined, through the developmental process, by the connection with the mother or the human environment. The significance of this connection with the environment, as it relates to the perception of borders, is defined by the ability of the environment (the mother) to allow the experience of delaying the border (between the mother [environment] and the baby).

A review of the psychoanalytical theories and literature provides the following conclusion: the core of the creation of phobias occurs as a result of the distortion of borders between the “I” and the external world; the existential space is constructed as a projection and expansion of the border between the “I” and the external world. Sibliey [7] claims, in regard to Melanie Klein’s theory, that the existential space is constructed from the separation between the “I” and the “other”. A distortion of this border may lead to a distortion of the space itself.

Agoraphobia - Geographical Aspects

In several articles, Davidson Bankey & Bondy [8,9] present studies about agoraphobia and geographical aspects through personal and group interviews. In these studies, they describe agoraphobia as an experience where the borders between the internal “I” and the external world collapse. In these studies, the phenomenological method is used, along the lines of Merleau- Ponty’s concept of the phobic experience (Merleau-Ponty stresses the composition wherein extreme experiences occurring in public places can be indirectly influenced by the “other”. The presence and projection of the “other” may allow the space to take on a dominant role and have a significant influence on the “I”). These studies deal with the transition between the “I” in space, and the self-cancellation of the “I” identity during phobic experiences. As regards those who suffer from agoraphobia, the home is perceived as a sanctuary, a shelter from the threats of the external world.

Symptoms of agoraphobia include: “a sense of shock, the inability to breathe, in another minute I’m going to die, no one can help me, rapid thoughts, strong heart palpitations, feeling sick, the legs feel paralyzed”. “Dizziness, lack of contact with others, feeling on the brink of an abyss. A feeling of loneliness and isolation from all external help, the feeling you are in a threatening vacuum”. “Losing one’s grip on reality, lack of sanity, loss of relation between one’s body and its borders, the body shrinks, shivers or sweats, “screams” or loses control; during the disturbing experience, it seems as if the body separates from consciousness.” The studies of Davidson and Ruth (2002) also reveal the following: Agoraphobia sufferers are characterized as being unable to defend their personal space. This is accompanied by a difficulty to cope with “others” (the external space). In extreme cases, over-sensitivity occurs; sufferers feel ‘trapped’ by their geographical space and the experience as one [8,9]. The experience of agoraphobia is described as a sense of depersonalization and the de-realization of those involved between internal and external borders. Sufferers describe the phobic experience as an unrealistic experience, as if the sufferer perceives the experience as a reflection in water, as a spatial illusion. Spatial elements are perceived as difficulties, which must be overcome. For example, rain, fog, darkness, and stormy weather are all considered as spatial difficulties, which must be overcome. Reality is like a ‘second skin’ (outside of the “I”), which is fragile and sensitive.

Ruth and Davidson are concerned with the characteristic of the agoraphobic experience as it effects the borders that form the “I”; the distortion of space serves to blur these external and internal borders and warps the borders between the “I” and the “other”. The loss of the identity of the “I”, as regards internal and external borders, are expressed in this threatening space. Davidson [10] says that for the agoraphobic, the world becomes miniscule; the world is perceived in a flash (like in a photograph). In short, these experiences begin from a place of crisis about one’s borders [11].

In the current study, we are concerned with the space, as a very active ‘player’, in the phobic experience, expressed by different types of spatial phobias, where the existential space of individuals who suffer from phobic disturbances becomes warped. In contrast to the accepted categorization in psychiatric literature, the current study proposes a new system of categorization according to geographic characteristics. The reason for this is that these parameters have been found to be of great significance in phobic experiences for a number of phobia types: spatial phobias (height, open spaces, enclosed spaces), environmental phobias (such as lightening, thunder, darkness and water), social phobias (fear of crowds). Different types of spatial phobias elicit different series of behaviors. In all cases, however, the space where the experience takes place undergoes a warping of the field or the borders, and the space in general becomes distorted. This study integrates two components: the psychiatric component and the geographic component. These two components are expressed by diverse possibilities in the phenomenological-existential model: between thoughts (inner awareness), as they are projected on the external environment (outer awareness) and the behavior of the body (bodily awareness) in response to anxieties that exist as a result of the distortions in the existential space during periods of spatial phobic disturbances.

The Phenomenological-Existential Model

The goal of interpretation is to construct a coherent model of characteristics about the existential space in the presence of distortions occurring within the existential space during phobic disturbances and to say that, in opposition to the psychological approach, there are a group of phobias that share a certain character – the distortion that occurs in the stability of the existential space – a tangible experience, although disproportionate to the experience of the actual material space (UMWELT). This is in contrast to other types of phobias where the existential space remains stable. The current study is primarily a phenomenological study and is, therefore, by nature, often defined as a study of beginnings. As we are ignoring the psychological aspect as regards the spatial dimension of phobias, I would like to examine, from the beginning, the phobic experience and the behavior of the existential space during this experience. In accordance with the phenomenological tradition, as recommended by Merleau-Ponty, I chose to focus on a number of extreme cases where individuals experienced phobic disturbances and to compare them with regular cases, which I didn’t feel compelled to discuss in detail on account of their being commonplace in nature [1].

Research Method

The model is built in stages

In the first stage, we will present situations described by individuals suffering from phobic disturbances, in their own words. In some of the cases, the individuals recreated and described the phobic experience in my presence; in one case, I used a phobic experience that I, myself, had undergone. These testimonies receive their primary interpretation from myself, according to how each testimony is coped with on an individual basis. Despite this, I edited the testimonies so that each one adds new elements toward understanding the spatial ‘behavior’ during a phobic disturbance, in addition to the contributions of previous testimonies. In the second stage, I will relate to conclusions, based on all of the examples, in order to construct a general model of the existential space during a phobic experience. In this stage, I will validate the phenomenological model with the accumulated knowledge in the professional literature from the fields of psychoanalysis and geography [12}. In the examples below, there is a possibility of space that ranks the awareness component towards the external world (space), the inner world (thought) and according to the body (bodily response), according to levels of difficulty.

Presentation of Case Studies

The trip to arbel cliffs

The space expands, moves back and forth for a while, and at times, remains static, it is stronger than I am, the incredible height is a constant threat, scary. I am afraid of falling, I am stressed; my body begins to seize up and becomes stiff. Against my wishes, I continue to look down; suddenly I am slightly dizzy. The space begins to twist and turn and move, like a vortex that threatens to suck me and everything else down. I feel that I am not in control; I am plagued by thoughts - I am going to be swallowed up by the space. I feel that the vortex of space makes the abyss look deeper and deeper and that me, and everything around me, will be sucked down into the abyss.

Floor 26 – eshkol tower, haifa university

My body begins to seize up, to become stressed; suddenly the space becomes dense, “warps”, for a split second. As I begin the ascent, I am afraid that the elevator will get stuck on one of the higher floors, my lips are a bit dry, my heartbeat is rapid. I am completely exposed to the view - the space, the height - suddenly I feel the building “move”, the surrounding space begins to spin around. The space within the room moves, contracts, expands and then stops, over and over again. The space becomes compressed, moves, I feel a loss of balance, the hallway is very narrow, and becoming narrower every second. I am dizzy for a split second; the space warps and then expands, the space begins to spin around.

Interpretation: external awareness

A distortion of the space stands out as a common factor in different directions and different ways; all of these sensations occur during a single phobic experience. For several seconds, the edges of the space seem to shrink, compressing the spatial field, while the borders expand until there are no borders at all and the entire spatial field has melted away. For seconds at a time, the space begins to spin in circular motions, threatening to consume everything in its tornado-like intensity. The sense of a lack of control is prevalent. During the phobic experience, the individual feels the intensity of the space. In regular circumstances, the space is built up around the individual, he is grounded, he is the base and the center of the space; the space provides the individual with a sense of stability, confidence, and calmness. In contrast, a lack of spatial stability leads to feelings of powerlessness in the face of external forces, especially as regards the external space and its borders. The loss of the ability to stabilize our existential space results in feelings of panic. The fact that the movement of the spatial borders moves first outside, in an infinite external expansion, and then inward, shows that the anxieties usually connected with agoraphobia and claustrophobia, are different facets of the same phenomenon: the threat of the distortion of the spatial borders and the individual alike.

In this situation, we can no longer doubt that for the phobic individual, this is a very ‘real’ experience, wherein the existential space not only threatens to become distorted, it is in fact actively distorted by the experience of the individual. All of the surrounding objects move in a unified manner, as if within a vortex or whirlwind; it is a spiral movement, like a funnel. Objects seems to shrink, appearing further and further away, stretching out into space as they are whisked away into the abyss. A distortion of the borders leads to a sense of general threat regarding the general field of space, the focal points and the connections between them are as one; all of the elements in the existential space are perceived as a single, indivisible entity.

In conclusion

During the phobic disturbance, the space ‘plays’ a dominant role in the existential space, where the borders disappear or collapse in upon themselves; the field becomes unstable, together with the focal points and the bridges. The space presents a tangible threat to the individual’s senses. The existential space threatens to become distorted - and more than this – the space is actually does warp, according to the perception of the phobic individual. The conclusion that may be drawn from the above is as follows: the perceived space becomes distorted in the presence of threats in the external world, while the physical world remains stable.

The flight to London

The individual begins to panic: “I think I am going to die, this is my last flight, I am losing control, I can no longer concentrate.” In this case, the space moves between instability and distortion. “Suddenly, it seems as if the plane is going to break apart, the plane begins to warp. Suddenly, we hit some air pockets; the space moves, intensifies.” The body seems to be paralyzed, sweating. There is an automatic and urgent drive, an intense desire, beginning from take-off, to get off the plane, but you are paralyzed: “Your body is paralyzed, frozen, in a panic. Afterwards, the body has a different response: you begin to sweat and hold on tightly to the chair: “My hands are sweating a bit and holding on very tightly to the chair.”

Interpretation

Dialog – External Awareness (space), Internal Awareness (thoughts) and Bodily Awareness (bodily responses). An obvious response to phobic experiences is the dialog that takes place within the individual as regards his awareness of his external environment, his bodily responses, and his thoughts. This awareness goes back and forth among these three realms until the individual manages to get a grip on reality once again. The deepest feeling or sense is the lack of control over reality and the self. This lack of control is accompanied by a feeling of complete chaos. On the one hand, there is a sense of having lost all control of one’s thoughts and feelings, while on the other hand there is a sense of having lost control of one’s body and the stability of the external space. No matter how much the individual tries to persuade himself that this warping of space is illusory in nature, he cannot liberate himself from this triangular sense of a loss of control (internal, external and bodily awareness).

During the movements of the individual’s awareness from the external world, his thoughts and his body, continuing to focus on the external world are accompanied by a sense of panic and a loss of control. Alternatively, focusing on thoughts leads to a struggle between the power of logic to stabilize the existential space, and the panic that has overtaken the individual by focusing on the external world. During these moments, the body feels as if it has been separated from all awareness, it is part of the world of objects, which cannot be controlled by the self.

The individual “I” perceives this loss of control in two ways: First, as a loss of sanity – the experience of the threat in the inner world, wherein elements from the external world are destabilized and become a tangible threat, is a frightening feeling, a precursor of bad things to come. Second, as the loss of one’s unique identity as it is connected to one’s bodily awareness. The “I” that is experiencing the phobic encounter stands at a sort of crossroads. One phobic experience may include several types of spatial phobias, claustrophobia, the fear that the plane will break apart, while another phobic experience may result in feelings of agoraphobia, the fear that the borders are disappearing into infinite space, while a third phobic encounter may result in acrophobia, a sense of extreme panic that the plane will fall into an infinite abyss. In other words, there is a crossover point of awareness – a dizzying and rapid dialog wherein the individual’s internal awareness exists and is nourished by several anxieties accompanied by panic, where the external awareness is involved in a diverse number of spatial phobias, wherein intensive spatial chaos reigns. In this chaotic space, all borders converge inwards upon the individual or expand into limitless space. The individual’s bodily awareness meanwhile responds variously to different situations of stress, vertigo, etc. - and all of this may be experienced during a single spatial phobic encounter.

Summary: There is a separation between the awareness of the external world, the internal world, and the body. The individual’s awareness frantically goes back and forth between the three, in an attempt to re-stabilize the existential space; often spurred on by panic and hysteria. This behavior serves to intensify the panic and feeling that the body is going to be swept away, down into the abyss, as a passive object. During this movement of the awareness between the external world, the individual’s thoughts, and his bodily responses, the attraction to focus on the external world is accompanied by feelings of panic and a loss of control, while focusing on thoughts leads to a struggle between the force of logic, which attempts to stabilize the existential space and the panic that has overtaken the individual, who’s attention is still locked within the external space. During these moments, the body is experienced as being separate from the individual’s consciousness, part of the world of objects, over which the self has no control. It is possible to view the levels of difficulty in the rapid movement of the awareness between the two. The conclusion drawn from these cases is that ‘awareness’ is a single entity and has a mutual dependence among all its factions: inner, outer and body. The moment one of these factions of awareness is harmed, all of the factions are harmed (See the Flight to London Case)

Kibbutz beit oren

I am walking along the path and suddenly I am afraid, I start to walk more slowly, closer to the mountain wall, the space seems to expand, I feel a slight sense of vertigo, the space begins to expand and contract, I am afraid of falling. Suddenly, the space begins to warp a bit for a split second, to expand and contract, I think I am going to fall, to lose my balance; this will make me fall, I will slip, and tumble down into the abyss.

Interpretation: inner awareness

The phobic encounter relates to the experience, which the individual identifies in advance / ahead of time. He builds up expectations according to the significance of the expected experience, and the ways in which he will cope with it. This characteristic raises the question whether the phobia is an undefined anxiety or an experience that reflects a tangible and realistic fear. The existential isolation of the individual experiencing the phobic encounter intensifies the anxiety, until he feels pure panic. This panic is brought on by the feeling that the external factors in the existential space seem to pose a tangible threat, as if a vacuum has suddenly opened up, wherein the external factors, such as objects in the space, are sucked in towards the individual; they appear to be huge in size, they lose all proportion as regards the individual’s inner awareness.

The “I” that experiences the phobic encounter undergoes a deep and intense feeling of anxiety; the individual makes desperate efforts to save himself from the chaotic and frightening regression that lies in wait every moment, behind the fragile veneer of reality. Anxiety is linked with the feeling that falling into the abyss will result in a complete loss of control and a loss of equilibrium. As a result, in his thoughts, the “I” combines catastrophic outcomes of sudden death or falling, which lead to bodily paralysis.

Summary: The phobic experience relates to a situation that the individual identifies from the outset. He builds up certain expectations about the significance of the expected experience and ways in which to cope with it. Often, anxiety-laden experiences relate to deep feelings of anxiety, connected to external elements that pose a real threat on the existential space; the level of anxiety may fluctuate in intensity, up until the point of complete panic and hysteria, wherein the individual senses a loss of control, a loss of reality, and a loss of sanity. During these times, the individual may feel that he is dying.

Conclusion: Anxiety is perceived according to different levels of difficulty, from mild anxiety to deep anxiety accompanied by panic. From this, we can conclude that anxiety exists as part of the internalization and projection processes, which are connected with threats, from both internal and external factors.

A case of agoraphobia from the film COPYCAT

Dr. Helen is a senior lecturer in criminology, specializing in serial murderers. One day, after her lecture, someone attempts to murder Dr. Helen in the washroom. As a result of this trauma, Dr. Helen develops agoraphobia – a fear of open spaces. She sits in her house, under the care of a live-in caretaker; she is addicted to alcohol and tranquilizers. In the movie, there are several scenes, where Dr. Helen is the victim of her phobic disturbance: Getting the Mail. Dr. Helen tries to get her mail from the entrance of her house. Suddenly, the hallway begins to warp, the windows become distorted, the walls begin to warp; the doorway at the end of the hall also begins to warp. Somehow, Dr. Helen manages to pull the letters closer, with desperate movements and extreme physical effort - her body seizes up, stretches, and once again, seizes up, until she finally manages to get the mail, after which she enters her house.

The Murderer in the Home of Dr. Helen: Suddenly, the entire hallway warps, Helen pushes up against the walls (with her face toward the wall); she clings to the wall. The walls begin to warp, the windows become distorted, Helen begins to beat the walls with both hands; she struggles to remain outside, her body writhes, stretches, and then shrinks in on itself, she struggles with the little strength remaining to her. She is in the hallway, she tries to walk forward; when anxiety grips her, she slowly goes back inside, step by step. The Crime Scene: Dr. Helen goes upstairs to the attic, she opens the door, the exposed space suddenly begins to warp, the floor becomes distorted, Dr. Helen feels dizzy, her body freezes up, she cannot move. Helen immediately closes the door and calls out for help; the murderer is running close behind her. Once again, she opens the door and suddenly the entire building begins to spin, the floor and the trees around the building all begin to warp, the other buildings surrounding the campus building also begin to warp, the low walls around the grounds begin to warp. (See the Case of Kibbutz Beit-Oren)

Interpretation (bodily awareness): The experiencing “I” is helpless, isolated and desperate, the individual experiences, in all its fullness, the fear of falling and the “fall” itself, intertwined with feeling of dizziness. The chain of awareness in this case is towards the external awareness, while the bodily awareness signals signs of anxiety; as long as the space is suspended in chaos, the bodily awareness disconnects and lacks all control. The sense of loss of control is prominent, the body is frozen, sweating, stressed; it becomes disconnected from awareness, is like a passive object that will at any moment be sucked into the abyss, losing all bodily control within the spatial chaos.

Summary: The experiencing “I” is helpless, isolated and desperate, the individual experiences, in all its fullness, the fear of falling and the “fall” itself, within the feelings of dizziness. Also prominent are feelings of a loss of bodily control. The body is perceived as a passive object in certain situations, while in other situations the body is dominant and active. We can see the different levels of difficulty pf bodily awareness: In the case of Beit Oren, the body behaves displays diverse levels of responses – stress, contraction, the body is not free, not calm; physical bodily fatigue results from the physical intensity of these responses. In the Crime Scene case, the body reacts by expressing a very high level of anxiety, the body is stressed, fatigued, and seizes up spasmodically. “Dr. Helen begins to beat upon the walls with both hands; she tries, at all costs, to remain outside.” The bodily awareness is nourished by the external and internal awareness, and vice versa.

Conclusion: Hence, we can conclude that the more the external and internal awareness is threatened, the more the bodily awareness creates this image. In cases where the space warps or threatens to become distorted, the body behaves accordingly to the threat.

Summarizing the model

In the following examples, we create a space of possibilities that rank the components of awareness according to level of difficulty, as regards, outer, inner and bodily awareness. It is important to mention that the different factions of awareness are nourished by one another; the individual’s consciousness skips back and forth between the three factions – inner, outer and bodily awareness. Awareness, at one and the same time, is a single entity, a part of the individual’s existential space. The awareness does not collect objects (harm or damage to one of the senses will not be expressed by the extinction of that same object, unless the damage affects the individual’s general approach to the world). When the awareness is imbalanced, the world may collapse into pieces or the content may become dissociative in nature. Normal functioning, similar to the objects in the world, take on an unrealistic significance [13,14]. According to Merleau-Ponty, the life-world is a real and tangible reality, an existing experience. The structures, referred to as the “life-world”, are the first way towards achieving experience and truth.

Awareness directed inward: The experiencing individual begins to panic “I think I am going to die, this is my last flight, I’m losing control, I can’t concentrate.” In this case, the phobic experience relates to a situation, which the individual identifies from the very start; he builds expectations – expectations about the significance of the expected experience and ways in which to cope with it. The individual feels an intense level of anxiety, but as of yet, no panic. “I am afraid I am going to lose my balance, “there is going to be an earthquake”, “the building will be blown away by the wind”, “and the building will collapse”. In other situations, the individual manages to overcome these phobic feelings and to achieve the chosen task, even if this is accomplished at a high personal cost; loss of control is a common feeling. In other cases, the individual may swing back and forth between feelings of intense anxiety and panic “I am not in control”, the most intense feeling is that of a simultaneous loss of control over reality and the self. This loss of control is accompanied by a feeling of complete chaos, a complete loss of control of both thoughts and feelings alike.

Awareness directed outward: In this case, the space moves back and forth between instability of the space and a warping of the space. “The plane will suddenly break apart, suddenly there is an air pocket, the space begins to move; the movement intensifies.” The fact that the movement of the spatial borders is first an outward movement of infinite expansion, and next an inward crushing type of motion, shows us that the anxieties connected with agoraphobia and claustrophobia, for the most part, are different facets of the same phenomenon – the threat that the spatial borders, including the individual himself, will become warped or distorted. In contrast, another case of phobic experience is where the spatial aspect goes from being stable in nature, to becoming distorted: “The space compresses, contracts, moves”, the space relaxes, it is once again stable”, “I go out of the room and walk towards the elevator, the space begins to shift, to move,” “the space becomes dense, moves”, “the hall becomes more and more narrow”. The space warps and expands for a few seconds; the space seems to spin around for a fraction of a second. In this case, the different directions of movement emphasize the common ground for experiencing spatial phobias. The spatial borders warp or threaten to warp; there is a general lack of stability in the existential space, including all of the objects within that space, including the individual himself. At times, the edges of the space seem to contract inwards, shrinking the spatial field and the focal points within it; at other times, the spatial borders seem to expand into infinity, until they seem to disappear completely. At times, the space seems to spin around in a circular motion, threatening to sweep the individual away, as in an especially strong whirlwind or a vacuum. In another case, the space seems to move back and forth between instability and a warping of the space in different directions “the space expands, it moves for a moment, then it is static, it intensifies”, “the space begins to move like a vortex, threatening to suck me and everything else down into the abyss”. “I feel as if the vortex of space makes the abyss deeper than it really is”. In these cases, there is no doubt that the phobic experience is a very real one, wherein the existential space doesn’t only threaten to warp, but actually does warp, according to the individual’s phobic perception. In this case, there is a loss of control of the external space. The space itself first threatens to expand until the space seems to break apart into nothingness; next the space begins to spin like a vortex, threatening to pull in the individual, and everything else along with him, into an infinite abyss. In yet another case, the space moves between stability and instability; the space seems to warp in several directions.

Bodily awareness: The body experiences a state of paralysis, sweating; there is a strong automatic response to get off the plane as it is taking off “my body freezes, I am paralyzed, I am extremely nervous”. Afterwards, there is another response, the body sweats profusely and the individual clings to his seat “my palms are sweating, they are grasping the seat very tightly”. During these moments, the body seems disconnected from all awareness, it is part of the world of objects, which are no longer under the control of the self. In contrast, in another case, the body, during a phobic experience, seizes up, experiencing physiological stress, dry lips, strong and accelerated heart palpitations, the individual clings to objects in the external world, the body is paralyzed, there is a sense of a loss of equilibrium. “I am in the elevator, my body begins to seize up, to cramp, I am stressed, I hold on tightly to the metal bar in the elevator, I get to the 26th floor, get out of the elevator, try to cling to the walls; I press up against the walls”, “my body is paralyzed, I want to return immediately to the elevator”. In this one phobic experience, we can see many common responses. The inability to stabilize his existential space causes the individual to experience feelings of panic and a loss of bodily control. In another case, the bodily response begins with paralysis and, at a later stage, the body seizes up, freezes, loses control, grabs on to something and the heartbeat accelerates. “I am walking along the path when suddenly, I feel paralyzed”, “I look with curiosity down the side of the cliff face, and then suddenly, I am in the grips of a strong force, my body becomes paralyzed, freezes, my body seizes up, loses control, I feel I must grab onto something – anything that will give me stability and security, clinging so as not to fall”. In this case, the strongest sensation is that of a simultaneous loss of control on reality and the self, a loss of control over the body and over the stability of the external space. In such situations, the bodily response is varied; it may be expressed by paralysis, sweating, or at times, by the individual grabbing onto something. We can see, that the body responds with a sort of desire to be attracted – like a passive object – to the deep abyss that it fears.

The conclusion we draw from the above cases is that the space actually warps according to the perception of the experiencing “I”. In the space of possibilities presented above, we can understand the behavior of the awareness - as regards the inner, outer and bodily awareness- because the threat to the existential space is real and the space actually does warp. The different factions of awareness are nourished by one another, chaos is created in the existential space, the individual is not only convinced that the spatial elements threaten to collapse in upon him, but rather pose a real threat to the individual by warping and becoming distorted. The spatial borders converge in on themselves; the field dissolves and threatens the individual. Hence, the elements in the external world pose a real threat because the individual feels that at any moment he, too, will warp and become distorted just like the external space. It is impossible for the individual to stabilize the existential space, the intensity of the anxiety increases until the individual is completely panicked. The body loses its stability and tries to keep its balance; the body behaves like a passive object. The space plays a very active role in the existential encounter during certain phobic encounters that may be termed ‘spatial phobias’; this differs from social phobias and environmental phobias, where distortions of the existential space do not occur.

The model and its implications

In the psychological and geographical literature, reasons and factors for phobic phenomenon and the existential space are mentioned, similar to the way it is presented in the current study’s psychological and geographical discussions.

According to Freud, a neurosis is a psychological disturbance that is formed when there is an inner conflict between any kind of primitive desire (originating from the Id), and the taboo involved in expressing it (originating from the Ego and the Superego). According to Freud, anxiety – a general feeling of fear from possible danger – is a sign of this internal struggle. In Freud’s opinion, anxiety is what causes neurotic behavior in these situations.

The Flight to London case – In this case, the space changes from being instable and becoming warped: “Suddenly, it seems as if the plane will come apart, the plane begins to warp, there are air pockets and the space begins to move, waver, intensify.” In contrast to this case, in the case of the 26th floor of the Eshkol Tower at Haifa University, the space changes from appearing stable to warping: “the space contracts back on itself, shrinks, moves”, “the space returns to normal, it is stable”, “I go out of the room towards the elevator, the space begins to move, to waver”, “the space contracts, sways”, “the hallway becomes more and more narrow”, “the space warps and expands for a few seconds, the space spins around for a split second”. These are expressions of responses of anxiety, projected from the inner world of the individual onto the threatening external world. Responses of fear are convenient for conditioning by means of stimuli that were previously neutral, when they are joined together with traumatic or painful events. However, today we know that many experiences that occur before, during or after a certain conditioning experience – whether the experience is traumatic or whether the conditioning occurs through observation – affect the nature of the fear, as it is experienced, conditioned or retained over the long-term. Experiencing long years of positive experiences with friendly dogs, before being bitten by a dog, will help the bite victim from developing an irrational fear of dogs. In order to understand inter-personal differences as regards developing and retaining phobias, it is important to understand the function of different life experiences, or the variables of experiences, which perhaps help us to differentiate between different types of people who undergo similar traumas.

Today we know that our cognition or our thoughts have a great influence on our emotional state, and vice versa. Studies conducted recently show that individuals who suffer from phobias are constantly “on the lookout” for their phobia-related stimuli or other stimuli connected to their phobia. Alternatively, people who do not suffer from phobias tend to avoid focusing on threatening stimuli. Likewise, phobia sufferers exaggerate freely when evaluating the likelihood that negative events will result from the object they fear. It is possible that this error encourages the preservation of phobic fears or their reinforcement over time. For example, people who suffer from acrophobia, both before and during the trip to a high place, are always on the lookout for the stimulus connected with heights. They ask the tour guide about the height of the mountain or cliff, whether it is dangerous, if there are cliffs, whether they will be climbing a dangerous incline, etc. Those suffering from phobias fear that with this journey their lives will end, that they will fall from the cliff into the abyss, etc. An examination of a clinical review of phobias shows that a phobic response may be an expression of numerous psychological disturbances, regardless of whether we are talking about an examination by means of psychiatric classification or a behavioral evaluation. Thus, a phobic response may be part of a clinical picture of depression, or a characteristic of a situation of diffusive anxiety. When the phobia appears as a dominant expression, the phenomenon is called a Phobic State or Phobic Disorder (APA). As regards the clinical definition of a phobia, it is important to note that phobic responses have different faces. It may appear as a mild fear, isolated from any one specific situation/object; it may appear as an intensive fear together with other psychiatric problems. Phobic disturbances in dominant situations, experienced by those who suffer from phobias causes serious limitations; for example, a housewife who suffers from agoraphobia (a fear of open spaces) will be limited when shopping in the supermarket, a businessman who suffers from acrophobia (fear of heights) will be limited as regards flying to other countries or too far distances within his own country. He will prefer to travel by car rather than get on an airplane. The opposite may occur in the individual who suffers from claustrophobia (fear of enclosed spaces), he will be very fearful of getting into elevators in order to start his workday in an office building, and will prefer to walk up the stairs. The above-mentioned limitations of those who suffer from phobias, as regards the internal factors, are part of the clinical picture of depression or a characteristic of diffusive anxiety. The individual who experiences the phobic encounter is threatened (both from outside and from within), from internal factors that are conflictladen, such as trauma and the like, as well as external factors that have to do with spatial elements, such as cliffs, abysses, deserts, elevators, caves, etc., and which pose a real threat in the existential space of the experiencing “I”.

This approach originates from the ideas of the philosopher Tillich [15], who claims that most mental problems stem from a lack of existential security, in addition to neurotic phenomenon that are connected to the repression of difficult emotional content. People who suffer from phobic disturbances suffer from a lack of existential security; the threats they experience in the existential space are accompanied by threats from the internal space such as anxiety, depression and panic, as well from external factors such as the spatial borders and fields, which appear to warp or converge inward upon both themselves and the experiencing individual – the space seems to surge outwards, and then once again, collapse inwards upon itself – causing a complete distortions of all borders. An unexpressed part of the design of the perception of the existential space relates to ontological security. The lack of existential security, together with the difficulty to cope with internal conflicts and spatial elements, create levels of difficulty for the individual experiencing the phobic encounter; these difficulties stem from a lack of existential security. This extreme difficulty causes fear to overtake those individuals that suffer from extreme phobic disturbances.

A key concept of Klein’s is that of anxiety. Anxiety is described as a key response of the “I”, regarding all of the events that originate on an internal level, although it may also relate to events that are connected to external struggles between the life drive and the death drive, and the type of relationships one has with internal objects. Every contact with or use of reality is always accompanied by anxiety, but at the same time, anxiety doesn’t allow us to live well and utilize reality to its best advantage. Klein explains this as follows: all of the relationships we have with the external world are based on a dialectic relationship of internalization and projection, re-internalization and re-projection (this process is referred to by Klein as ‘modification of the internal via the external’ and vice versa). Hence, internal destruction is projected or shifted outward to the breast and the world it represents. Hence, the baby’s aggressive feelings at the beginning of his life are projected onto the mother. This projection is not only a transference process of these or other things outward beyond the border. Through this transference process, the border comes into being and is marked out, between the internal system and the external system. The projection, therefore, is also a sort of distortion of the differentiation of the border as regards what comes from inside and what is experienced as external contact. From this point, the concept of existential space develops. Internal and external factors pose a real threat to the baby’s existential space. The baby lacks the tools to cope with these threats, which then lead to anxiety, fears and internal conflicts within the baby. The baby cannot cope with these difficulties; it is from this point onward that the concept of existential space is created; during the moments when these conflicts are most intense and numerous, they multiply and distort the differentiation of the border between what comes from inside and what is perceived as external contact. The elements of the mind and the connection with the external world are symbolic in that they reflect and express the human consciousness into symbols and shapes in the surrounding external world. In the existential world of the “I”, even as regards what seems to be ‘normal’ building, anxiety is a sign of a mechanism; relationships between the “I” and the “other” during phobic disturbances are created in one of two ways – through either internalization or projection. This is also the cause of the distortion in the perception of the field and the border in the experience of the phobic individual. The distortion of the border is a result of defective internalization of the elements in the external world, and their defective projection onto the external elements. Distortion of the differentiation of the borders - or the lack of borders - may lead to more and more extreme behavior, until the “hoped for” border is found. In extreme cases, where there is a lack of borders or a distortion of the borders, this may lead, for example, to extreme phobic disturbances, wherein the elements in the external world pose a real threat to the existential space of the “I” who is experiencing the phobic encounter. For example, the cliffs and the abyss are examples of both sides of acrophobia; the disconnected and foreign landscape, such as the desert or open spaces – and it makes no difference if the landscape is green or brown – when we are speaking about agoraphobia; the elevator, the train or the cave, etc., when we are speaking about claustrophobia. The threats in the external world cause deep anxiety, the existential space threatens to warp; as a result, the individual loses his grip on reality and on himself. A loss of control accompanied by a sense of absolute chaos develops, along with a loss of control over one’s thoughts, one’s body, and the stability of the existential space.

The messages described in Shoham’s theory [6] in context with the paranoid aspect of phobic experiences occurs when the individual experienced the phobic disturbance in an extreme way – the external elements threaten the individual, the individual finds it very difficult to stabilize his space, and his loss of control causes the space to be both the ‘pursuer’ and the ‘pursued’, as the borders and the field contract inward towards the individual or retract outward until the borders virtually disappear; this pulls the field, along with the focal points and the bridge outward, until they too disappear. Hence, we may conclude that people suffering from spatial phobic disturbances are characterized by paranoia, where the space is both the pursuer and the pursued.

Summary

After reviewing theories and literature from the fields of psychology and geography, we can conclude that the core of the formation of phobias is connected to the distortion of the borders between the “I” and the external world; the existential space is constructed by a projection and an expansion of the border between the “I” and the external world. According to the above theories that relate to borders, we may find core reasons for why the space may play a dominant and important role in some of the phobias (as regards those same spatial phobias).As the theories explain, there is a distortion of the border between the “I” and the external world, and this is the base for building the existential space between the human consciousness and the surrounding external environment. Spatial phobic disturbances upset the balance in the chain between the inner awareness and the outer awareness; the borders threaten to warp, together with the field, the focal points and the bridges. The threat is real; it is a threat wherein the individual’s existential space collapses.

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

Existential space is very significant as regards the individual’s ability to function. Spatial phobias distort the existential space; this, in turn, causes considerable damage in the daily life of the individual suffering from phobic disturbances. The psychological literature that discusses phobias focuses on the subjective feelings of the individual and on his anxieties. In the current study, we address and discuss space as an important component in understanding phobias. I claim there is a group of spatial phobias, where the elements in the external space pose a real threat (i.e., an abyss, high bridges, elevators, airplanes, deserts, caves, caverns, etc.) to the individual who has internal anxieties. There is a common factor to phobias – the anxiety that accompanies their appearance, and their existence in the existential space. Thus, we may conclude that anxieties exist within the existential space; and these anxieties are real. When anxieties are perceived in the existential space, they are projected onto the external world; while at the same time, the existential space warps. This distortion poses a real threat to the experiencing individual; this, in turn, leads to significant limitations in daily reality of the “I” and damages his ability to function properly (damaging his awareness and his surrounding environment).

There are different types of spatial phobias: acrophobia (fear of heights), claustrophobia (fear of enclosed spaces) agoraphobia (fear of open spaces). All of these phobias are classified as one group, referred to as ‘spatial phobias’. There are different types of spatial phobias that intersect one another during individual phobic experiences (see the Flight to London case). The psychological discussion raises the possibility to propose a new classification of phobias. The existing classification relates to different world contents, such as intensity of anxiety, the factors that arouse the phobic phenomenon, or the level of specificity of the situations that arouse phobic responses. The proposed classification has three categories; each category relates to three dimensions: the generalized dimension of phobic phenomenon (whether they are specific phobias or general phobias); the dimension of the intensity of the phobic symptoms (the differentiation between anxiety and panic); and the dimension that relates to the origin of the phobia, which differentiates between social factors, environmental factors (such as lightening, thunder or water), and spatial factors (such as heights, enclosed spaces or open spaces). Therefore, according to my proposition, we may classify each and every phobia according to these three categories (see Table 1). In contrast with the DSM classification, my classification emphasizes the spatial phobias and the distortions that occur in the existential space of the experiencing “I”. For example, claustrophobia - fear of enclosed spaces; agoraphobia – fear of open spaces; acrophobia – fear of heights. This is in contrast with social and environmental phobias, wherein distortion of the existential space does not occur. In Davidson’s [8,9] study, she researched agoraphobia and its geographical aspects, defined the term ‘phobic disturbance’, and explained the phenomenon and its characteristics. She examined agoraphobia by describing the experiences of individuals and groups, and explained how the borders collapse between the “I” and the “other” during the phobic experience, how the space warps (without going into depth or details), discusses the phenomenological experience along the lines of Merleau-Ponty’s proposal, the loss of identity of the experiencing “I” during the phobic encounter, the threat to the existential space of the “I”, the difficulty to define borders in the existential space, and the very real threat experienced by the “I” during the phobic experience. Davidson describes the agoraphobic experience as “an experience wherein the individual feels that he cannot be seen by others; he has become invisible.” Internal as well as external borders collapse in the existential space of the agoraphobic individual.

In the current study, in contrast to Davidson’s study, a new classification of spatial phobias is proposed: claustrophobia, acrophobia, agoraphobia; environmental phobias: water, lightening, thunder, darkness, animal phobias; and social phobias. Furthermore, I also present an innovative, existentialist, phenomenological model, according to descriptions provided by individuals who suffer from spatial phobic disturbances, who give detailed accounts of the warping and spatial distortions that occur during the phobic encounter. I then relate to one of the spatial spheres (the physical sphere: field, border, focal, point and bridge) that exist in the existential space, after which I provide a detailed interpretation about the spatial behavior during the phobic disturbance. In my thesis, the borders become distorted, dragging the field and the additional spatial elements (focal points and bridges) along with it. In the phenomenological model, there is a space of possibilities as regards spatial behavior during the phobic experience, which helps to understand the space. The space of possibilities is expressed in terms of levels of difficulty and levels of intensity; for example, the space is static, stable, warped, spins around, becomes funnel-like, etc., and also according to the behavior of the individual’s awareness. Awareness: Internal, external and bodily awareness are part of the existential space. In addition, in the geographic discussion, I adopt Shoham’s theory of borders, discuss Melanie Klein and Winnicott, and relate their theories to the phenomenological descriptions of individuals suffering from spatial phobic disturbances, which pose a real threat to their existential space. Moreover, I show how the space becomes distorted during the phobic experience, how the borders collapse, disappear, or contract inwards upon the individual. In this way, I attempt to show how important and significant the borders are in the existential space, and the desire of the individual to attempt to stabilize his existential space and its borders. In the current article, I describe a case of a phobic attack and how one individual may experience several spatial phobias during one phobic experience (see the Flight to London case); I also discuss the distortions that occur in the existential space. In this study, I show how the space functions as a very active ‘player’, during the phobic experience and the serious importance of the space in the phobic experience [16-20].

In this paper, the phenomenological description and the distortions that occur in the existential space during a spatial phobic experience provide food for thought as regards geographicspatial components connected to the phobic experience, and the distortions that occur in the existential space; the borders and fields are very significant as regards the daily activities of the phobic individual’s reality. Feelings in the phenomenological model express not only feelings about spatial distortions, but also paranoid characteristics where the space is both the pursuer and the pursued. The feelings of individuals who suffer from spatial phobic disturbances are very real. From their point of view, the existential space is like the scene of a temporary earthquake; the borders either collapse in upon the individual or disappear completely. There is no chance of the individual stabilizing his existential space; just as there is no chance of him stabilizing his feelings of security. These feelings are accompanied by great anxiety, together with a deep and dominating existential sense of complete isolation.

During the phobic experience, the individual’s awareness or consciousness has a significant function. In so-called ‘normal’ people, the individual’s awareness is constantly focused on both the inner and outer worlds. In contrast, in individuals who suffer from phobic disturbances, this continuum is broken (during the phobic experience) – the individual’s awareness undergoes a split between the human consciousness and the surrounding external environment. During a spatial phobic encounter, the conceptual space, as perceived by the individual, appears to warp, while the actual physical space remains stable. For example, as regards the fear of heights: in relation to the spatial aspect, the conceptual space warps, the abyss is a symbol of the lack of all borders, the borders become distorted, together with the field, as if it has been swallowed up by the space, the focal points and the bridge are swallowed up together with the field and the border [21-26].

The phobic experience is a sort of deep anxiety, which poses a real threat on the existential space of the phobic individual. The cases described in the empirical section of the study describe the phobic experience as a real experience, wherein the existential space doesn’t only threaten to become distorted; it actually does warp, according to the perception of the phobic individual. The deepest feeling at this time is the loss of control over one’s reality and one’s “I”. This loss of control is accompanied by a feeling of absolute chaos. On the one hand, this includes a loss of control regarding one’s thoughts and feelings, resulting from a loss of control over one’s own body and a loss of stability in the external space. On the other hand, no matter how much the phobic individual tries to convince himself that the distortions he perceives are mere illusions, he cannot rid himself of this threefold loss of control (as regards his bodily, internal and external awareness). One of the most common responses during phobic experiences is the way one’s awareness seems to skip back and forth between the outer world of the external environment, the bodily world, and the inner world of thoughts and consciousness [26-31].

The threats experienced by the baby already exist in developmental stages from the day the baby is born into the world, and they continue to be experienced throughout childhood, as he is constantly in contact with external and internal factors that threaten him. The stresses connected with the birth process, the sudden transition from the womb to the struggle of life outside of the womb, the shock of having to build a separate “I”, and the disappearance of the pantheistic pre-oral world, the disappearance of the breast and the warm and omniscient, all-giving mother figure, and the transition toward building a narcissistic “I” are all events that the baby’s awareness strives to cope with – with great difficulty. Accordingly, these excruciating shocks of separation have a concretizing effect and help to construct the core of identity in the baby’s personality; they are an initial source of understanding of the difficulties we face during the first years of our lives, which are filled with fears and anxieties, painful inter-relationships, connected to the expulsion of the kindness of the paradisiacal, pantheistic, pre-oral world. It is from this point that the concept of existential space develops. Initially, phobias are formed as irrational anxieties. The threats absorbed by the baby include internal and external threats. The dichotomy between the external world and the internal world is dialectic in nature; in the case of phobias, psychologists have largely ignored the external factors [32-36].

Conclusion