The Inclusion of Deaf Students in Higher Education: Didactic-Pedagogical Strategies Applied to the Teaching and Learning Process

Everton Luiz de Oliveira1*, Adriana Paula Fuzeto2 and Paulo Afonso Franzon Manoel2

1Unifafibe / Bebedouro University Center, Brazil

2Brazilian Education System (SEB) / Ribeirão Preto, Brazil

Submission: April 18, 2020; Published: June 11, 2020

*Corresponding author: Everton Luiz de Oliveira, Unifafibe / Bebedouro University Center, Brazil

How to cite this article: Moyun Wang, LiyuanZheng. The Factual Versus Counterfactual Reading of Affirmative Versus Contrapositive Conditionals in Chinese. 002 Psychol Behav Sci Int J .2020; 15(1): 555902. DOI:10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555902.

Summary

Although the process of school inclusion in Brazil has existed for more than two decades and has been supported by documents and public policies, there are still many difficulties for students with disabilities in the process of teaching and learning. Therefore, the objective of this work was to develop and apply pedagogical strategies aimed at learning and the inclusion of deaf students in the Civil Engineering course. Fifty students without disabilities, three teachers and one student with hearing impairment participated in this study, all linked to the Civil Engineering course at a Higher Education Institution in the interior of the state of São Paulo. Participants were divided into 10 Working Groups. Data collection took place in 2017, in the discipline of Study and Research Methods and Techniques, whose students developed and applied a teaching methodology (several pedagogical strategies) to assist in the inclusion of deaf students entering higher education in the field of Civil Engineering. The stages of the study took place at three specific moments: Stage 1- the participating students conducted research on online sites on the subject of hearing impairment and, subsequently, these findings were discussed in the classroom; Stage 2 - the participants experienced awareness-raising activities addressing the theme of inclusion of people with disabilities; Stage 3 - each group was tasked with creating / elaborating four signs (Sign Language) for four specific terms / words in the Engineering area. The data were collected from Field Diaries and the use of the online platform “Google Drive” for the sharing of digital files produced by the participants. The results demonstrated the necessity and pertinence of the use of the Brazilian Sign Language in the teaching of the deaf in the subjects of the engineering courses. In addition, the participants (with and without hearing impairment) noticed an improvement in the inclusion process of students with deafness in the classroom, insofar as they could also contribute to the elaboration of a list of Signs for specific terms / words of the engineering and that were archived in the form of gifs on a digital platform on the internet.

Keywords: Curriculum; University education; Special education; Inclusion; Hearing deficiency

Introduction

The education of deaf people began in Brazil with the creation of the Instituto dos Surdos Mudos, in 1857, in Rio de Janeiro, currently known as the National Institute for the Education of the Deaf - INES. According to a survey carried out by the WHO in 2011, people with hearing impairment in Brazil would represent approximately 14% of the total population, with almost 28 million with some type of hearing impairment [1].

Since then, with the advent of major regulatory frameworks for the education of people with disabilities, such as the Salamanca Declaration [2], coined in 1994, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, approved by the UN in 2006 [3] and the National Special Education Policy from the Perspective of In clusive Education [4], there was an advance in policies, legal documents and actions aimed at the inclusion and accessibility of deaf people to teaching and school learning, with the strengthening of actions for the implementation and structuring of LIBRAS (Brazilian Sign Language) as the official language of this population segment in educational establishments.

The Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) was established, in Law nº 10.436 / 2002 [5], as the official language of deaf people and so that it must be admitted as a language of the same importance as French, English, Italian or any other official of a given country. Libras must be recognized as a legal means of communication and expression for the deaf community. In this sense, according to the aforementioned law [6], it can be learned that Libras represents a “form of communication and expression, in which the linguistic system of a visual-motor nature, with its own grammatical structure, constitutes a linguistic system. transmission of ideas and facts ”inherent to the culture and historical materiality of Brazil. According to Saussure [7] and Leite [6] Sign Languages share the basic properties of the natural languages representative of each country, so that each has their own Sign Language, which is used by deaf people for communication, learning and social interaction. Honora [8] points out that Sign Languages emerge from the very social and cultural dynamics experienced by deaf people, reaching a level of complexity and expressiveness that can be compared to those used in Oral Languages. That said, it is necessary to understand that they have grammatical structures, meanings and rules of employment and composition, giving them the status of Languages. In this conceptual and analytical perspective, there is also the concern and efforts of many theorists, activists, entities and the academic community to give scientific status to Sign Languages [6].

Although Decree No. 5.626 / 05, which regulates Law No. 10.436 / 2002, specifically dealing with access to school for deaf students and providing for the inclusion of Libras as a curricular subject, the importance of training and certification of teachers, instructors and translators / Libras interpreters, there is no mention of the Higher Education sphere, that is, the initiatives seem to focus on the attention to basic education of deaf people. In this context, it is also noticed that even though this public (deaf people) in the face of Brazilian educational legislation, they have insured their rights and guarantees to accessibility, inclusion and Specialized Educational Service (AEE) in the Special Education modality, which it must cross all levels of education, from Early Childhood Education to Higher Education [6,9,10], it is evident the scarcity of proposals, actions or programs for school inclusion aimed at Higher Education. Regarding the educational reality addressed by the present study, it is worth mentioning the efforts of the Higher Education Institution in which this research was developed, since the LIBRAS discipline is offered in the curricula of teacher training courses and the hiring of interpreters to assist all deaf students enrolled in undergraduate and graduate courses. Thus, the objective of the present study was to develop and apply pedagogical strategies aimed at learning and the inclusion of deaf students in the Civil Engineering course.

Methods and Materials

Fifty students without disabilities, three teachers and one student with hearing impairment participated in this study, all linked to the Civil Engineering course of a Higher Education Institution in the interior of the state of São Paulo. Participants were divided into 10 Working Groups. Data collection took place in 2017, in the discipline of Study and Research Methods and Techniques, using field diaries and using the online platform “Google Drive” for sharing digital files produced by participants, which addressed several teaching methodologies (pedagogical didactic strategies) to assist in the inclusion of deaf students entering higher education in the area of Civil Engineering.

i. Stage 1 - the participating students conducted research on online sites on the subject of hearing impairment and, later, these findings were discussed in the classroom. In addition, teachers made available scientific articles and reports that addressed the theme of inclusive education.

ii. Stage 2 - at this time, practical experiences and awareness activities were organized and applied, addressing the theme of inclusion and the “universe” of the deaf person. The purpose of this stage was to bring together and discuss with the participants issues related to the universe of the deaf person and people with disabilities in general, focusing on issues of accessibility and school inclusion.

iii. Stage 3 - This stage of the study was subdivided into two specific moments, namely: I) Development of pedagogical strategies for deaf students: the Working Groups developed and tested educational didactic strategies that could contribute to the inclusion and accessibility of deaf people to the content specific to Civil Engineering; II) Elaboration of Signs (Sign Language) to represent specific terms / words in the Engineering area: each Working Group was tasked with creating / elaborating Signs (Sign Language) specific terms / words in the Engineering area.

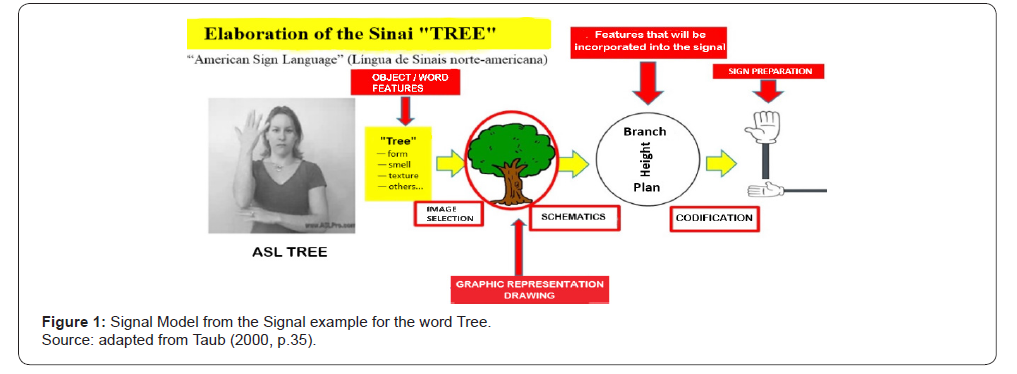

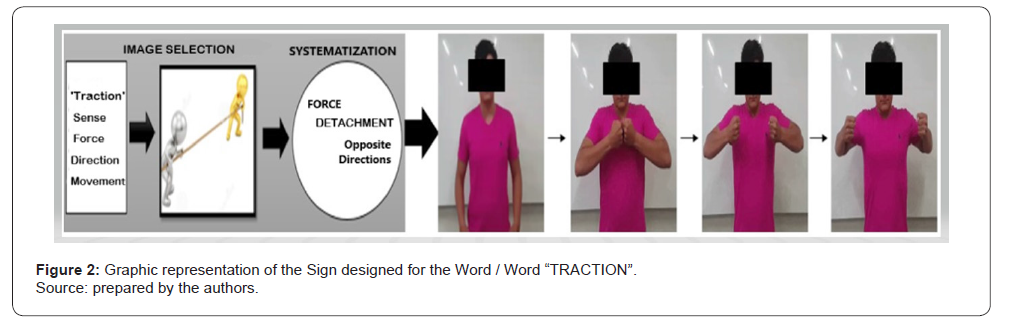

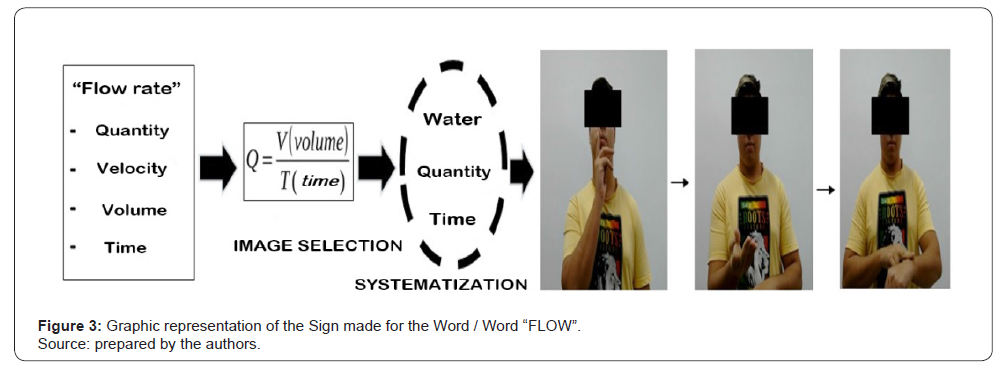

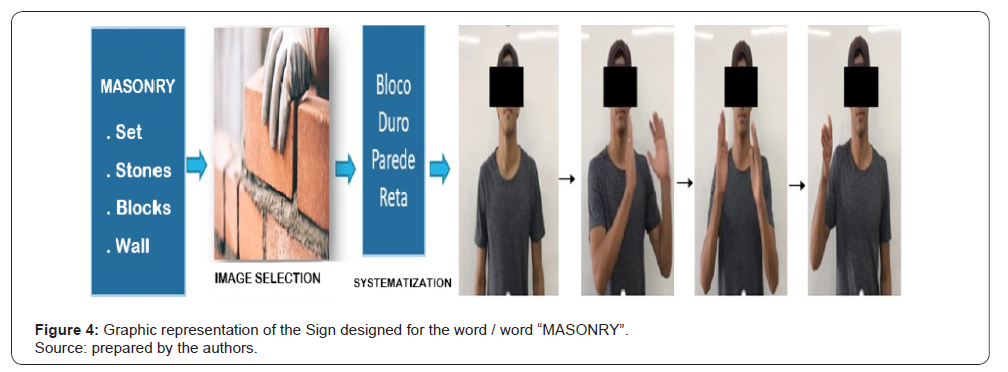

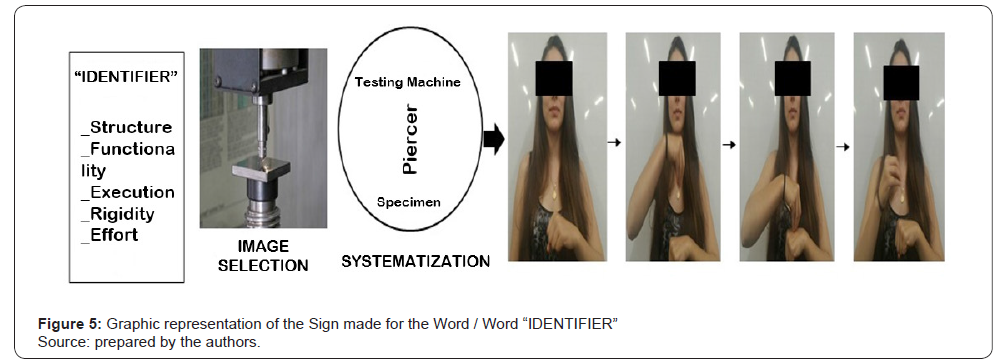

In this study, we used the contributions of Stokoe [11]; Leite [6] and Taub [12] to structure the Signs for the Words / Vocabularies specific to the area of Civil Engineering. Regarding the Model for the Development of Signs proposed by Taub [12], which decisively embodied the stage of elaboration of the Signs, it has to be a structured method, initially, from the selection of a Word / Vocabulary and, then, it proceeds with the separation and organization of a set of characteristics referring to that Word / Vocabulary. Subsequently, it comes to the moment of Image Selection (selection of a representative image for the Word / Vocabulary) and its graphic representation through a drawing. Finally, we proceed with the Schematization phase, in which the main characteristics of the Word / Vocabulary are to be incorporated into the Sign, and the Coding phase, when the Sign itself is created. For a better presentation of the method adopted by Taub [12], follow below, Figure 1.

Results and Discussion

Next, the main findings obtained through the study will be presented. Based on the results obtained through Step 1, recorded in field diaries, the participants found a moment to reflect and resolve doubts with their colleagues and teachers in the classroom. It should be noted that the fact that we have the presence of a deaf student among the participants contributed to the explanation and approximation of contexts and practical matters also in the lives of deaf people. For Borges; Costa [13], despite the need for prior knowledge and information to contribute to the inclusion of deaf students in the school environment, there is a shortage of pedagogical actions in relation to these issues, as teachers still use precarious teaching methods and they often do not have adequate preparation to teach the contents to deaf students, showing a barrier to learning.

Based on Oliveira [14], it is clear that the Brazilian education system has numerous difficulties and / or pedagogical flaws when trying to understand the learning potential and specificities of the deaf or hearing-impaired student. In this sense, the participants showed great interest and exchanged experiences and knowledge that were obtained through readings and access to pedagogical, pedagogical and practical knowledge regarding life, reality and the dynamics inherent to deaf people. Regarding the findings referring to Step 2, it is clear that this activity consisted of carrying out interventions and experiences that would give students without disabilities and the deaf student a critical reflection and problematizations focusing on understanding the nuances of the world of the person with deafness before the conventional environment (listeners) in situations of daily life and learning context. With this step it was possible to bring all participants in the universe closer to deaf people, unveiling their potential and the physical, educational, communicational, and social interactions barriers that permeate their materiality. The findings obtained during Stage 3 were organized according to their respective Moments, being then I and II. Therefore, for the presentation of the findings narrow to this Stage and its respective Moments, it was decided to structure two other subsections, namely: _ Development and implementation of Pedagogical Didactic Strategies; _ Sign Formatting (Sign Language) from specific Words / Vocabularies used in Civil Engineering.

Development and implementation of didactic strategies

As already noted, during Stage 3 (Moment I), the Working Groups developed and tested Pedagogical Didactic Strategies that could contribute to the inclusion and accessibility of deaf people to the specific contents of the Civil Engineering area. It should be noted that strategies were tested both by the deaf student included in this class and by the other participants (classmates without disabilities). The justification for the realization of Moment I is due to the scarcity of studies and research that addressed teaching and learning strategies and models that contributed to the inclusion of deaf students in Higher Education and, even more specifically, regarding the reality of the Course of Civil Engineering, perspectives apprehended from Step 1, in which students were able to research and access the universe of didactic and scientific productions related to this theme of the inclusion of deaf students in Higher Education.

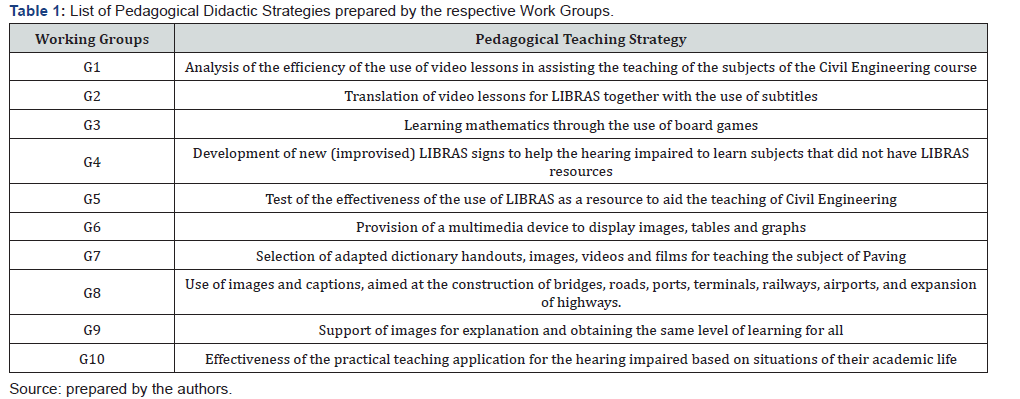

According to Espote, Serralha & Comin [15], a probable explanation for the lack of preparation of teachers and educational institutions for the inclusion of deaf students in the school environment is reflected by the scarcity of published research related to this theme. These authors, when conducting a survey of the number of publications of scientific articles specifically related to these themes and which were published in numerous sites and online platforms for scientific research, found that there was an extremely small amount of studies addressing the inclusion of students with deafness (deaf) in the academic field, warning that this subject is practically neglected in the field of educational research and by society in general. That said, it will follow with Table 1 for the presentation of the Didactic Strategies developed and applied by the participants during Stage 3 - Moment I, distributed in their respective Working Groups.

The G1 Working Group, proceeding with the analysis of the efficiency of the use of video classes to assist the teaching of the subjects of the Civil Engineering course, selected three volunteers

(one with deafness and the other two using sound insulation) and verified the correctness index for mathematical exercises performed after viewing the video lesson. The deaf volunteer got 100% correct answers and commented that the subtitles of the video lesson did not help much, but he said he liked the experience of learning through the video lesson being easy. The volunteers who used sound insulation obtained 69% and 80% correct answers, and they claimed that the method was inefficient for them. One of the participants reported “Having in mind a minimal base on the subject, it is possible to understand some terms individually, but in general it is difficult to assimilate the entire content, as I am unable to read the caption and observe the examples.” [...] “Although my concentration has increased, the lack of hearing the tone of voice in which a certain subject is explained makes it even more difficult to understand” he concludes. The G2 tested with 10 volunteers (one with deafness and another nine using sound insulation) the effectiveness of video lessons that had the content translated into LIBRAS and also the subtitles resource inserted. The nine listening volunteers stated that what helped them was the caption, since the fact that they did not know LIBRAS, made this resource insufficient. The volunteer with deafness stated that the LIBRAS used in the video class had some Signs that were not adequate / correct and this hindered their good understanding, a problem that was overcome by the presence of the LIBRAS interpreter that contributed to a better understanding of the video.

For the G3 strategy, board games with four volunteers were used (one with deafness and the other three with sound insulation). For the deaf student it was necessary to explain step by step the realization of the mathematical tasks used in the games but managed to obtain 100% correct answers. Listening volunteers who were using sound insulation also obtained 100% correct answers but took longer to solve the mathematical exercises. In the G4 proposal, the improvised elaboration of specific Signs for the Chemistry area was suggested based on videos that demonstrate and explain each one of them, the procedures were carried out quickly and in order to meet an immediate need to adapt content to the deaf student , as suggested by Silva (2011) in the study in which he proposed the creation of specific Signs for the Classical Mechanics discipline at the Mackenzie SP institution. In this initial assessment of the applied methodology, it was found, from the oral testimony of the deaf student and his interpreter that the videos with the Signs and the way they were made was practical and didactic, as it reduced the time from one sign to another, which streamlined the relationship between the student and the interpreter.

The G5 tested the effectiveness of using LIBRAS by applying tests to deaf students and hearing students after teaching content from the Topography and Hydraulics disciplines. The results obtained by the tests showed a low number of correct answers in the questionnaires and the average of correct answers was higher for the hearing students. Because it is content of great complexity, it is speculated that only the use of LIBRAS is insufficient for the teaching of these disciplines. The methodology selected and developed by the members of the G6 proved to be simple and easy to be applied, requiring only suitable locations and the device developed. Observing what people described about what they learned, it was noticed that they understood practically everything that was intended to transmit. According to them, images and animations helped a lot in understanding, these resources being responsible for practically everything that was learned, according to the participants’ report.

In the strategy developed by the G7, a dictionary-handout was used, applied only to the hearing-impaired student, who described that the method in question presented valuable information for understanding the topic addressed. With regard to the use of images, several pictures and figures on the matter were presented and these were selected according to the amount of information they transmitted. Given the resource of images, it can be seen that the deaf student presented an analysis and assimilation of the idea presented more quickly than the hearing deaf students. Therefore, for students without disabilities, this method was considered good, but incomplete, as they reported that they were unable to fully understand the topic. When using the pedagogical didactic strategy to use images and captions, aimed at the construction of bridges, roads, ports, terminals, railways, airports and the expansion of highways, they observed that this approach facilitated and promoted the understanding of the contents.

Elaboration of signs (sign language) from specific Words / Vocabularies used in civil engineering

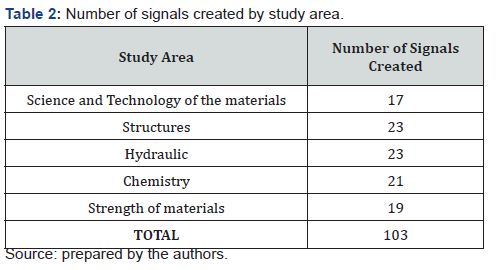

The findings related to Momento II (Stage 3) deal with the elaboration and / or structuring of Signs (Sign Language) for the specific Words / Vocabularies in the area of Civil Engineering and which still did not have their representation in LIBRAS (Brazilian Sign Language). The elaboration and construction of the Signs followed the guidelines expressed by Stokoe [16] from the structuring of the American Sign Language, using the three parameters for its formatting, being the location, the configuration of the hands and the movement. Other references such as de Leite [6] through his linguistic study on the segmentation of LIBRAS and its basic components, and also by Taub [12] addressing signal formation models, served to subsidize efforts focused on the elaboration / construction of Signs with the participants. The Specific Words / Vocabularies in the area of Civil Engineering were selected by the professors (researchers) during the classes that were taught to students by teachers of the Civil Engineering Course during the second semester of the year 2017. The classes selected for observation and selection of Words / Vocabularies were defined based on the availability of days and times of the researchers, since they had to accompany the classes throughout their development and record the main Words / Vocabularies presented during the classes taught by teachers from different subjects in the curriculum of the Civil Engineering course. At the end of each theoretical class, the researchers presented all the selected Words / Vocabularies to the teachers who taught the classes, so that this set of Words was better delineated by both and, immediately after the Words / Vocabularies were presented in a general framework to the participants and then, they were distributed randomly among the Working Groups. In this way, the Working Groups went to the college’s computer and technology laboratory to prepare the respective Signs and share them through digital files with the online platform “Google Drive”.

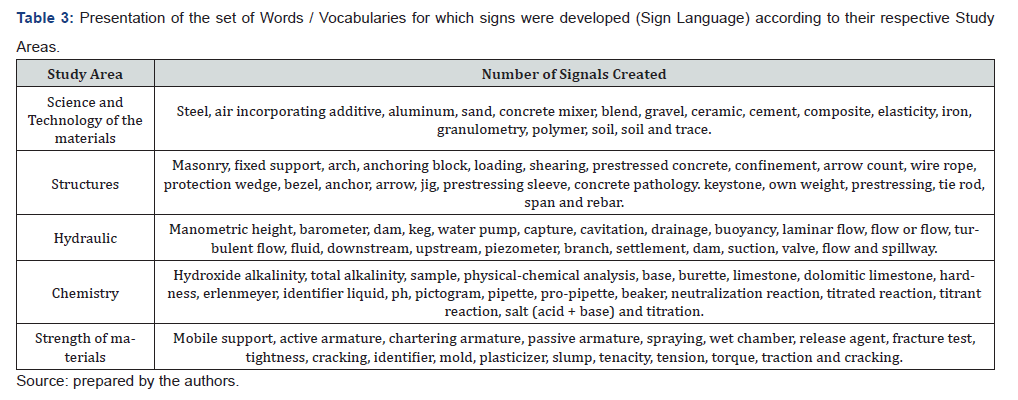

Table 2 below shows the Study Areas for which the Signs (Sign Language) were prepared, as well as the total number of Signs prepared by the participants.

The fact that the Signs (Sign Language) in their final version were presented in the “GIF” format does not allow their complete viewing in this space, as they are “animations”, that is, short videos in which the participants present the correct execution of each Sign created by the Working Groups. However, for a better detail of the findings obtained in Moment II regarding Stage 3, it will be followed by the presentation of the structural part (graphic representation) of some Signs that were elaborated in this study (Figures 2-5).

It is worth mentioning that the construction of the Signs took place in a collective and participatory way, using the contributions of LIBRAS interpreters who work in our Teaching Institution, providing specialized assistance to students with hearing impairment regularly enrolled in undergraduate and graduate courses. from different areas. The collaborative participation of both interpreters and students with hearing impairment (deaf) and research professors were essential for the Working Groups to obtain the theoretical, technical and specialized support necessary for the configuration and construction of the Signs (Sign Language) that they were gradually created and shared by the study participants.

Thus, below, Table 3 is presented, next to which all the Words / Vocabularies that were selected for Moment II are outlined, that is, the specific Words / Vocabularies in the area of Civil Engineering that did not have Signs in the Brazilian Language of Signs (LIBRAS) and whose elaboration Signs (Sign Language) was entrusted to the Working Groups.

Final Considerations

The present study contributed for the participating students to develop an experimental research of great social relevance, while it also contributed to the improvement of the inclusion process of the student with deafness in the academic scope of the Civil Engineering Course of our Higher Education Institution. Ademias, one can contribute to the context of sociability and awareness of the entire local academic community in the face of the inefficiency of resources and pedagogical didactic strategies currently employed in the teaching and learning process of deaf or hearing impaired students in Higher Education.

References

- Cajazeira PEL, Bastos V (2016) Journalism and pedagogical strategies for students with disabilities. Federal University of Cariri, Juazeiro do Norte, Brazil.

- Salamanca declaration and line of action on special educational needs (1994) UNESCO, Brazil.

- (2006) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, approved by the UN General Assembly in December 2006. United Nations Organization.

- (2008) National Policy on Special Education from the Perspective of Inclusive Education, MEC / SEESP.

- (2002) Provides for the Brazilian Sign Language - Libras and provides other measures. Federal Official Gazette, Brasília, DF, No. 10,436, of April 24, 2002.

- Leite TA (2008) The segmentation of the Brazilian sign language (libras): a descriptive linguistic study from the spontaneous conversation between deaf people, 280f. Thesis (Doctorate in Linguistic and Literary Studies in English) - Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

- Saussure F (1970) General linguistics course. Cultrix, São Paulo, Brazil.

- Honora M, Frizanco E, Lopes M (2009) Illustrative Book of the Brazilian Sign Language. Ciranda Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil.

- (2011) Provides for special education, specialized educational assistance, and other measures. Decree No. 7,611, of November 17, 2011.

- (1999) National Guidelines for Special Education in Basic Education (2001) CNE / CEB. CNE / CEB Opinion No. 17/2001.

- Stokoe WC (1976) A dictionary of American Sign Language on linguistic principles. Linstok Press, Silver Spring, Maryland, United States.

- Taub SF (2000) Iconicity in American Sign Language: Concrete and metaphorical application. Spatial Cognition and Computation 2: 31-50.

- Borges FAB, Costa LG (2010) A study of possible correlations between teaching representations and the teaching of Science and Mathematics for the deaf. Science and Education Science & Education (Bauru) 16: 567-583.

- Oliveira LA (2001) The deaf's writing: text and conception relationship. Juiz de Fora Federal University, Brazil.

- Espote R, Serralha CA, Comin FS (2013) Inclusion of the deaf: an integrative review of the scientific literature. USF Psychology.

- Stokoe WC (1976) A dictionary of American Sign Language on linguistic principles. Linstok Press, Silver Spring, Maryland, United States.