Diagnostic Corelates of Depression Among Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Children

Shalan Joodah Rhemah Al-Abbud* and Haneen Hameed Ismail

Department of Psychiatry, Imamain Kadhimain Medical City, Iraq

Submission: April 07, 2020; Published: May 18, 2020

*Corresponding author: Shalan Joodah Rhemah Al-Abbudi, Department of Psychiatrist, Imamain Kadhimain Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq

How to cite this article: Shalan J R A-A, Haneen H I. Diagnostic Corelates of Depression Among Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Children. Psychol 00162 Behav Sci Int J .2020; 14(5): 555900. DOI:10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555900.

Abstract

Background: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is a syndrome of inattention, distractibility, restless, over activity, impulsiveness, and other deficits of executive function. Diagnosing major depressive disorder in children can be confronting.

Objectives: Estimation of sociodemographic characteristics and Depression among ADHD children

Methods: A cross-sectional study conducted on ADHD children attending 3 child psychiatry centers, Baghdad, Iraq. Data collected during the period March 1st, 2019 to September 1st, 2019. All ADHD children were included. Current unstable medical illnesses, not cooperative, not give their consent were excluded. Sociodemographic variables of were compiled using a questionnaire filled through a direct interview. Conners’ Global Index - Parent Version used to confirm the diagnosis. Birleson Depression scale was used for diagnosis and assessment of depression.

Results: A total of 105 ADHD children, age range 6-11 years. First rank order (42.9%), not at school (64.8%), family referral (98.1%), and separated parent (6.7%), dead father (8.5%). About 60% of fathers were of low education. Employed father was 33.3%. More than half of mothers were of low education. ADHD with psychiatric comorbidity 37%. Depressed ADHD 12.4%. Significant correlation of depression was found with age group school level, states of living with parents, parents’ marital status, and traumatic events.

Conclusion: There is a significant statistical correlation of depressed ADHD with; age, school level, status of living circumstances, parent marital status, traumatic event exposure. Suggesting that stressful social circumstances may be a key mechanism

Keywords: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; Depression; Psychiatric comorbidity; Traumatic event exposure; Neurodevelopmental type; Mental disorder; Psychiatric disorders; Depressive disorders; Medical practitioners; Mental health

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a syndrome of inattention, distractibility, restless over activity, impulsiveness, and other deficits of executive function [1]. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a mental disorder of the neurodevelopmental type [2]. It is characterized by difficulty paying attention, excessive activity, and behavior without regards to consequences which is not appropriate for a person’s age. There are also often problems with regulation of emotions [3]. The symptoms appear before a person is twelve years old, are present for more than six months, and cause problems in at least two settings (such as school, home, or recreational activities). In children, problems paying attention may result in poor school performance. Additionally, there is an association with other mental disorders and substance misuse [4]. Diagnosing major depressive disorder (MDD) in children (5-12 years of age) can be confronting. Important debates continue regarding the validity of psychiatric diagnoses, especially in children and adolescents. Longitudinal research, however, has continually demonstrated that most adult disorders have their origins in childhood, and most childhood disorders have consequences that persist to adulthood [5]. There is evolving evidence to suggest MDD, as we currently understand it, can even exist in pre-schoolers. Over time, children with ADHD may become frustrated and demoralized because of their symptoms. They may develop feelings of a lack of control over what happens in their environment or become depressed as they experience repeated failures or negative interactions in school, at home, and in other settings. As these negative experiences accumulate, the child with ADHD may begin to feel discouraged. Typically, in these situations ADHD symptoms appear first and the depression comes later. These negative reactions are common in individuals with ADHD and some expert claim that up to 70 percent of those with ADHD will be treated for depression at some point in their lives [6]. In addition to being saddened or demoralized because of ADHD, children may also experience a true depressive illness. To date, studies indicate that between 10- 30 percent of children with ADHD may have a separate serious mood disorder like major depression [7-9].

Aims of Study

i. Estimation of sociodemographic characteristics of ADHD.

ii. Estimation of prevalence of Depression among ADHD children.

iii. Estimation of diagnostic correlate of depression among ADHD children.

Methods

Design and setting

This is a cross-sectional study conducted on ADHD children attending 3 child psychiatry centers in Baghdad, Iraq.

Data collected

During the period March 1st, 2019 to September 1st, 2019.

Inclusion criteria

All children with ADHD were included.

Exclusion criteria

Current serious or unstable medical illnesses that cannot complete the interview; not cooperative; and who did not give their consent to participate were excluded from the study.

Data collection Tools

Sociodemographic variables and clinical characteristics of ADHD children were compiled using a questionnaire filled through a direct interview. Conners’ Global Index-Parent Version used to confirm the diagnosis of ADHD. Ten-Item Conners’ Global Index Parent Form-CGI-P is composed of ten items used to evaluate the frequency and severity in the last week of the child’s impulsivity, emotional outbursts and motor hyperactivity. Scoring is age and gender specific. The CGI-P has an internal reliability coefficient of 0.94. A test-retest reliability coefficient over a six to eight weeks interval was 0.8 for CGI-T. Scores over 65 are in the clinical range [10]. Birleson Depression scale used for diagnosis and assessment of depression. The Depression Scale for Children was developed in 1978 as part of a Master of Philosophy Thesis at the University of Edinburgh. The scale emerged from a longer inventory of 37 items that had been described in the literature as associated with major depressive syndromes in childhood. The test-retest reliability of the Scale on an independent sample showed satisfactory stability (0.80). Individual items had a reliability coefficient of 0.65-0.95. The Scale’s corrected split-half reliability was 0.86 showing good internal consistency. The linearity of Scale items was assessed by factor analysis. A rotated matrix produced 5 factors that together shared 61% of the total variance. These factors were very similar to those found in adult studies. [11,12].

Definition of variables

The independent variables evaluated to explain depression were socio-demographics (age, gender, school level, marital status of parent, level of education of parent, occupation of parent, economic status, source of referral, living circumstances, smoking and alcohol of parent) and clinical characteristics (psychiatric comorbidity, family history of medical and psychiatric disorders, traumatic events exposure).

Statistical analysis

Statistical package of social sciences (SPSS) version 20 was used for data entry and analysis. Categorical variables were tested using chi square test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ethical Issue: Official approvals were granted from the officials in the study setting. Informed consent was obtained from each participant family to be included in this study. Names were kept anonymous and interviews were conducted with full privacy

Results

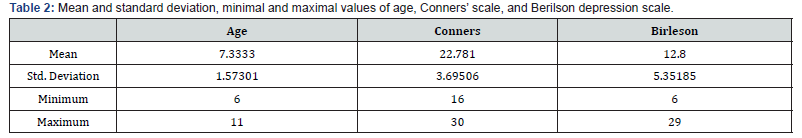

A cross sectional study includes a total of 105 ADHD children. Male 83.8%, female 16.2%. Age 7.33±1.57. More than two third of children were age 6-7 years (65.7%). First rank order (42.9% ), live in their own house (71.4%), not at school (64.8%), normally delivered (61%), half of them within middle socioeconomic status (51.5%), separated parent (6.7%), dead father (8.5%). The education of the father was; 29.5% primary school, 26.7% institutes and colleges, 21.9% intermediate school, 15.2% secondary school, and 6.7% were illiterate. About one third of father occupation was employed 33.3%, 55.2% free work. More than half of mother was of low education; 28.6% primary school and 25.7% illiterate. Occupation of mothers; 85.7% housewife, employed 12.4%. About 71.4% were without family history of chronic medical illness and 70.6% without family history of chronic mental illness. Depressed ADHD children were (12.4%) [13]. About 50% of Depression found in age group below 10 years, mostly male (69.2%). living in illegal houses were 15.3% of depressed child. The level of school shows more depressed in those not at school 46% and the second class 23%. Most depressed children were the first rank order among siblings (55.8%), normal labor (69.2%). About 46.1% live with mother, 38.5% live with both parents, and 15.4% live with grandmothers. The economic status was low 46.1%, middle 38.5%, and high 15.4%. the parent marital status; married and live together were 46.1%, separated parent 38.5%, and dead father 15.4%. the education of parents of depressed ADHD children; father education were institutes and colleges 46.1%, primary school 30.8%, intermediate school 15.4%, and illiterate 7.7%. Mother education was colleges and institutes 38.5%, primary school 23.1%, illiterate 23.1%. The occupation of father was; free work 46.1%, and employed 23.1%. The occupation of mother 92.3% were housewife and 7.7% employed. Family history of medical illnesses was 30.8% and family history of psychiatric illnesses 38.5%. The psychiatric comorbidity was 30.8%. The exposure to traumatic events was 15.4%. There is a significant statistical correlation of depression with: age group (P<0.001), school level of the child (P=0.048), the status of living weather both parent, mother, or grand-mother (P<0.001), parent marital status (P<0.001), traumatic event (P=0.048) (Tables 1-4) (Figure 1).and illiterate 7.7%. Mother education was colleges and institutes 38.5%, primary school 23.1%, illiterate 23.1%. The occupation of father was; free work 46.1%, and employed 23.1%. The occupation of mother 92.3% were housewife and 7.7% employed. Family history of medical illnesses was 30.8% and family history of psychiatric illnesses 38.5%. The psychiatric comorbidity was 30.8%. The exposure to traumatic events was 15.4%. There is a significant statistical correlation of depression with: age group (P<0.001), school level of the child (P=0.048), the status of living weather both parent, mother, or grand-mother (P<0.001), parent marital status (P<0.001), traumatic event (P=0.048) (Tables 1-4) (Figure 1).

Discussion

The study showed Male 83.8%, female 16.2%, with more than 5:1 male: female ratio. More than four-fifth of the participants were boys aged 6 to 9 years. This finding agrees with most previous studies, underlining the risk of ADHD in this age group.13 The typical male preponderance was also noted in this study. The male to female ratio in this study was lower than Cuffe, Moore & McKeon study [14] and higher than the study by Adewuya & Famuyiwa [15] that reported 2:1 from their sample. However, according to Biederman et al. [16], the risk of ADHD is the same for boys and girls. The reports of male preponderance might be due to referral bias as males are more likely to present with more externalizing symptoms, such as hyperactivity and aggression, than females, which made it easier to be recognized and referred for treatment. The current study showed a comorbidity of depression about 12.4%. Depression may be a reaction to unpredictable environmental stressors such as being rejected by peers, getting made fun of by others, or thinking that school is a negative and overwhelming place. Depression may run in the family or may be more directly linked to biological or genetic causes; therefore, a separate diagnosis and specific treatment for symptoms for depression would be more appropriate.

The prevalence of depression among ADHD children of the current study is higher than many studies Ghandour et al. [17]: Among children aged 3-17 years, 3.2% had current depression. Charles J, Fazeli M [18]: Childhood MDD point prevalence is 1-2%, when compared with adolescent-onset MDD. The prevalence increases to 4-5%. These rates underestimate the number of children who do not meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for MDD, but who present to primary care with clinically significant depressive symptoms and functional impairment [18]. Mojtabai R [19]: The 12-month prevalence of MDEs increased from 8.7% in 2005 to 11.3% in 2014 in childhood [19]. Lima et al. [20]: Depressive disorders among children prevalence of 0.3% to 7.8% in children below 13 years old [20]. In Brazil, the prevalence of childhood depression among children below 14 years old varies from 0.2% to 7.5% according to the assessment method used [21-23]. Egger & Angold [24]: Depression is relatively uncommon in pre-pubertal children (1-2%) and rates differ little between boys and girls [24].

The result of this study is within the accepted range of many studies. Moffitt et al. [25]: prevalence of major depressive disorders range from 10%-17%. Furman L [26] estimates of the prevalence of depression among patients with ADHD range from 13% to 27%, while clinical sample reports have run as high as 60%.25 Conversely, among children and adolescents with depression, various studies have reported widely varying rates of ADHD (from less than 5% to more than 50%); a recent study in very young children reported a rate of 42% [26,27]. Spencer T [28]: A total of 10-40% of children with ADHD shows depression with symptomology of low or irritated mood, loss of interest and pleasure of usually enjoyable activities, sleep disturbances, and reduced appetite [27,28].

There is a significant statistical correlation of depression with: age group (P<0.001), school level of the child (P=0.048), the status of living weather both parent, mother, or grand-mother (P<0.001), parent marital status (P<0.001), traumatic event (P=0.048). The family variable of ADHD in this study that was found to be positively correlated with ADHD was having parents who were divorced or being a child of a single parent (P<0.001). Reduced family cohesion and chronic conflict may adversely affect marital or partner relationship resulting in the dissolution of the marriage. Divorce is permissible in the culture and religion of people in Iraq and it may explain this finding. This finding agreed with the report by Biederman et al. [29] from a similar study who found that reduced family cohesion, chronic conflict and parental psychopathology are associated with ADHD. This is further supported by findings from Fischer [30]. The reason for this might be because people in the study setting would not like to discuss issues about their marriage with strangers, even if they were medical practitioners, for cultural reasons [30].

Conclusion

ADHD, the most common diagnosis in child psychiatry, appears to be more challenging to diagnose when there is a comorbid depressive disorder. There is a significant statistical correlation of depression of ADHD children with; age, school level, status of living circumstances; weather parent, mother, or grandmother, parent marital status, traumatic event exposure.

Recommendations

It is important to consider depression when interviewing children with ADHD. Prevention, early detection, and treatment of depression and other common mental disorders in childhood age groups are major goals of public mental health initiatives. Adaptation and broad implementation of effective treatment and prevention programs remains a challenge. The growing number of depressed children who do not receive any mental health treatment calls for renewed outreach efforts, especially in school mental health and counselling services and paediatric practices where many of the untreated depression may be detected and managed. More studies need to be done to verify the relationship of one disorder with another, if the individual who has depression can have ADHD, and verify the causality between depression and being ADHD.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn), American Psychiatric Publishing. Arlington, USA, pp. 59-65.

- Sroubek A, Kelly M, Li X (2013) Inattentiveness in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuroscience Bulletin 29(1): 103-110.

- Faraone SV, Rostain AL, Blader J, Busch B, Childress AC, et al. (2019) Practitioner Review: Emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - implications for clinical recognition and intervention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 60(2): 133-150.

- Erskine HE, Norman RE, Ferrari AJ, Chan GC, Copeland WE, et al. (2016) Long-Term Outcomes of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Conduct Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 55(10): 841-850.

- Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott M, Snowling MJ, et al. (2015) Rutter’s child and adolescent psychiatry. (6th edn), Wiley-Blackwell, Milton, United States, p. 5.

- Cusi AM, Nazarov A, Holshausen K, MacQueen GM, McKinnon MC (2012) Systematic review of the neural basis of social cognition in patients with mood disorders. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 37(3): 154-169.

- Hamilton JP, Etkin A, Furman DJ, Lemus MG, Johnson RF, et al. (2012) Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis and new integration of baseline activation and neural response data. American Journal of Psychiatry 169(7): 693-703.

- Suzuki H, Botteron KN, Luby JL, Belden AC, Gaffrey MS, et al. (2013) Structural-functional correlations between hippocampal volume and cortico-limbic emotional responses in depressed children. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience 13(1): 135-151.

- Guerry JD, Hastings PD (2011) In search of HPA-axis dysregulation in child and adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 14(2): 135-160.

- Grizenko N, Ricardo M, Rodrigues RM, Joober R (2013) Sensitivity Of Scales To Evaluate Change In Symptomatology With Psychostimulants In Different ADHD Subtypes. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22(2): 153-158.

- Birleson P (1981) The Validity of Depressive Disorder in Childhood and the Development of a Self-Rating Scale: A Research Report. J Child Psychol Psychiat 22: 73-88.

- Birleson P, Hudson I, Grey-Buchanan D, Wolff S (1987) Clinical Evaluation of a Self-Rating Scale for Depressive Disorder in Childhood (Depression Self-Rating Scale). J Child Psychol Psychiat 28(1): 43-60.

- Busch B, Bierderman J, Cohen LG, Sayer JM, Monuteaux MC, et al. (2002) Correlates of ADHD among children in pediatric and psychiatric clinics. Psychiatric services 53(9): 1103-1111.

- Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeon RE (2005) Prevalence and correlates of ADHD symptoms in the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Attention Disorders 9(2): 392-401.

- Adewuya AO, Famuyiwa OO (2007) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among Nigerian primary school children: prevalence and comorbid conditions. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 16(1): 10-15.

- Biederman J, Mick E, Farone SV (2000) Influence of Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry, pp. 36-42.

- Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, et al. (2019) Prevalence and Treatment of Depression, Anxiety, and Conduct Problems in US Children. The Journal of Pediatrics 206: 256-267.

- Charles J, Fazeli M (2017) Depression in Children. Focus 46(12): 901-907.

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B (2016) National Trends in the Prevalence and Treatment of Depression in Adolescents and Young Adults. Pediatrics 138(6): e20161878.

- Lima NNR (2013) Childhood depression: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 9: 1417-1425.

- Avanci J, Assis S, Oliveira R, Pires T (2012) Childhood depression. Exploring the association between family violence and other .psychosocial factors in low-income Brazilian schoolchildren. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 6(1): 26.

- Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J (2010) The worldwide prevalence of ADHD-is it an American condition? World Psych 2(2): 104-113.

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, et al. (2010) How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine 40(6): 899-909.

- Egger HL, Angold A (2006) Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 47: 313-337.

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, et al. (2010)How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine 40(6): 899-909.

- Furman L (2005) What is attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? J Child Neurol 20(12): 994-1002.

- Luby JL, Heffelfinger AK, Mrakotsky C (2003) The clinical picture of depression in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(3): 340-348.

- Spencer T, Biederman J, WIlens T (1999) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity. Pediatr Clin North Am 46(5): 915-927.

- Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Kiely K, Guite J, et al. (1995) Family-environment risk factors for attention deficit hyperactivity disorders: a test of Rutter’s indicators of adversity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52: 464-470.

- Fischer M (1990) Parenting stress and the child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 19(4): 337-346.