Reflective Functions and Parent Training in ODD

Frolli A1,2, Cavallaro A2, Bosco A3, Caruso G2, Vignola R2, Lombardi A3, Rega A4, Operto FF5 and Ricci M C3

1University of International Studies of Rome, Italy

2Serapide SPEE - Specialization School in Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy for Developmental Age Disorders, Italy

3FINDS - Italian Neuroscience and Developmental Disorders Foundation, Caserta, Italy

4University of Naples Federico II, Italy 5 University of Salerno, Italy

Submission: March 8, 2020; Published: March 19, 2020

*Corresponding author: Frolli Alessandro, Disability Research Centre of University of International Studies of Rome Via Cristoforo Colombo, 200, Rome – Italy

How to cite this article: Frolli A, Cavallaro A, Bosco A, Caruso G, Vignola R, et al. Reflective Functions and Parent Training in ODD. Psychol Behav Sci Int J .2020; 14(3): 555895. DOI:10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555896.

Abstract

Background Oppositional Defiant Disorder falls into the category of Disruptive Behaviour Disorder, Pulse Control and Conduct Control characterized by hostile, negative and provocative behaviour towards authoritative individuals, and conditions that involve problems of self-control of one’s emotions.

Aim: This study aims to demonstrate how improving self-perception and fostering informed parenthood can foster more competent emotional development in children.

Sample: The sample therefore includes 30 children divided into two 15 test groups who had been diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) age range 4-6 years.

Methods: After having validated the diagnosis, we started parent training: it is an intervention aimed to improving the relationship between parents and children, increasing the ability to analyze educational problems that may arise, increase knowledge of psychological development of children and principles that govern them, disseminate effective educational methods and make family life and educational problems that can arise more easily manageable. showed an improvement of reflective functions to subscale certainty and uncertainty on perception of one’s own and others’ mental states of RFQ test after development of parent training in both groups, and this can lead to behavioural improvements.

Keywords: Reflective Functions (RF); ODD; Parent training; Mentalizing; Emotional dysregulation; Emotional development

Introduction

Oppositional Defiant Disorder falls within the category of Disruptive Behaviour Disorder, Pulse Control and Conduct Control [1], which is generally characterized by hostile, negative and provocative behaviour towards authoritative individuals and all those conditions involving self-control issues of own emotions. Negativism has proved to be physiological in the early years of life and intensifies at the age of two to the extent that, according to some researchers such as Brazelton [2], this stage of life is often referred to as the “terrible two”, in which a child begins to perceive himself as an autonomous subject, separated from the mother, committed to asserting himself even through recurrent denials. Therefore, it might be difficult to tell a healthy separation-detection process apart from a pathological behaviour. This distinction can be made through an evaluation of the child and the contexts in which he lives, as well as by assessing the severity and persistence of his opposition. The disorder begins to manifest itself clearly around the age of 3, at the time of entering nursery school, which is normally a stressful time for the child, as it requires an effort of adaptation, regulation of his behaviour and continuous interaction with peers: children with this disorder often fail to adapt and integrate. The onset of first symptoms occurs mainly at a preschool age and hardly ever beyond the early stages of adolescence; an onset after the age of sixteen is very rare in both sexes [3]. These children have frequent outbursts of anger, do not respect rules, are irritated by the presence of others, causing tiredness, discouragement and frustration in those who seek to interact with them. Assumption of such behaviour may be due to a number of causes, including social learning: these children have often been exposed to antisocial behavioural patterns, were urged to adopt aggressive attitudes to defend themselves or were reinforced when showing aggressive manners in solving social conflicts. Usually, as newborns, they used to display a very high temperament and intense motor activity. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the aetiology of Oppositional Defiant Disorder: some of them refer to the risk factors of a temperamental nature, such as a high emotional reactivity, a low level of frustration tolerance or hyperactivity traits [4]. Other hypotheses, however, would give greater importance to environmental aspects, such as too rigid and inconsistent educational practices [5], family instability or exposure to particularly stressful changes [6] and neglect or abuse. In particular, a strict education is thought to create a vicious circle in which more attention is given to the problematic behavioural aspects of the child; in such upbringings, a child would make his own image of the “bad” child, reiterating unwanted behaviors. Seemingly, a lack of reinforcement of positive actions might make a child feel less encouraged to implement them [7]. Children who have not shown aggressive behaviour in early childhood are unlikely to develop high levels of aggression in later years [8]. About the influence of biological factors, lower levels of cortisol [9] a.k.a. stress hormone, have been found in children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder, which may suggest hypoactivity of central nervous system in the area of impulse control and in the prediction of negative consequences of a given action. There is also a lack of physiological activation, which is expressed through lower levels of sensitivity to danger [10]. In cognitive-behavioural model of anger and aggressive behaviors in evolutionary age, a child’s aggressive emotions and behaviors are regulated by the way the child perceives, processes and mediates environmental events, rather than by the events themselves [11]. Anger therefore arises as a subjective reaction to everyday problems and frustrating events. In these children, in fact, there is little control, little reflexivity, difficulty in taking a different perspective from their own, absence of problem-solving skills and overall, a cognitive deficit that prevents activation of thought processes that functionally guide behavior [12]. For subjects with a predominance of symptoms related to anger and irritability, emergence of an emotional dysregulation disorder is more likely. Jenkins et al. [13] state that a lack of awareness of their emotions could be at the root of the emotional dysregulation trait, which in turn is held responsible for bad behavior aimed at moderating subjective suffering, such as self-injurious gestures [14]. Various research shows that poor regulation of emotions, both positive and negative, might result in an exteriorization of the child’s behavioural issues, in school as well as family contexts, while an excessive inhibition in regulation of emotions is associated with a tendency to internalize problems and to develop social anxiety [15- 17]. Parental fitness is also assessed by the criterion of reflexivity of Fonagy [18], which refers to that set of psychological processes underlying the ability to mentalize [18] also understood as the capacity for abstraction and reflective awareness, which plays a central role in cognitive and developmental psychology. Fonagy, et al. [19] have validated the first self-report that measures RF, the reflective functioning questionnaire (RFQ) and that investigates precisely the parental reflective functions. The present study aims to compare two parents’ training models throughout a period of six months: one of which is based on rational emotional education [20], opposed to the other based on the Circle of Security [21], an attack- based model focused on parental regulation and reflex. The aim of our study is to ultimately demonstrate that by improving self-perception as a parent and embracing conscious parenthood, one can foster a more competent emotional development in the child and reduce externalizing behaviors typical of the ODD. It is not enough to improve behavioural strategies and reduce irrational thoughts through a standard cognitive intervention, but we must broaden parental reflexive function by promoting more stable and mature mentalization processes: a competent parent can structure accurate emotional reflection processes.

Materials and Methods

Participants

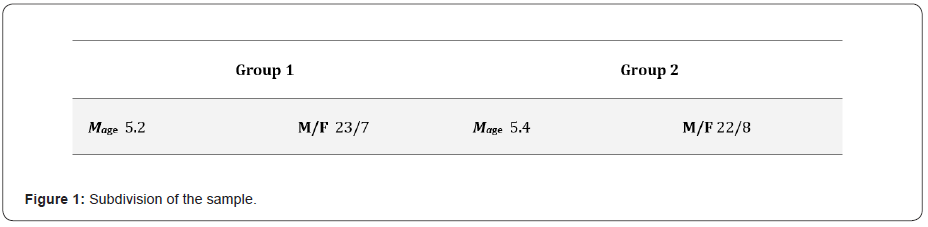

In this study we initially considered a sample of 72 subjects. From this sample we excluded 12 children who had parents with a positive perception as caregiver, resulting from the administration of the PSI/SF [22] and valuable reflexive functions derivative from the administration of the RFQ questionnaire. The total sample therefore includes 60 children who had been diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) [1] following the administration of K-SADS-PL DSM 5 [23] to their parents, and whose parents had a low self-perception, of the mental states of their child, and absent reflective functions on parental awareness arising from the administration of the RFQ and PSI/ SF questionnaire. The presence of an externalizing disorder was confirmed by the administration of CBCL to parents and teachers; the administration of K-SADS-PL 5 also allowed the exclusion of other neuropsychiatric childhood disorders, while Raven’s Matrices confirmed an intelligence in the normal range. Data was collected from FINDS Neuropsychiatry Clinics by qualified psychologists. The sample included preschool children age range 4-6 years and was divided into two subgroups according to the type of parent training disposed for parents, as discussed in the next paragraph. The first group included 30 children (23 males and 7 females) Mage =5.2; the second group included 30 children (22 males and 8 females) Mage =5.4. (Figure 1)

Procedures and tasks

The Protocol used consists of the following tests: K-SADS-PL [23], PSI/SF [22], RFQ [19], CBCL [24].

K-SADS-PL DSM 5 is a diagnostic interview for the evaluation of psychopathological disorders (past and present) in children and adolescents according to the criteria of DSM-5. In particular, it allows to detect the presence of: mood disorders, psychotic disorders, anxiety disorders, disturbances of attention deficit and disruptive behaviour, substance abuse.

RFQ. It evaluates the level of mentalization possessed through two subscales, which evaluate the certainty (RFQ_C) and the uncertainty (RFQ_U) of self and others on mental states. Higher scores at these subscales indicate two distinct RF disturbances, respectively, hypomentalization and hypermentalization: the hypomentalization reflects actual thought and poor understanding of mental states of self and others, while hypermentalization describes that attitude directed toward the identification of overly certain and detailed patterns of mind and mental states not supported by evidence.

PSI/SF. A self-assessment questionnaire used for the identification of parental stress and for the early identification of factors that can compromise a child’s normal development. The instrument is based on the hypothesis that the stress experienced by a parent is the joint result of certain characteristics of the child, characteristics of the parent himself and a series of situations closely related to parenthood. In the short form it is composed of 36 items, divided into three subscale: Parental Distress (PD), which analyzes the level of stress that a parent experiences, resulting from an altered perception of his parenthood, Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction (P-CDI), focusing on the fact that the parent perceives the child as not meeting their expectations and the interactions therefore don’t reinforce their parental perception, and Child Difficult (DC), which analyzes some characteristics of the behaviour of the child that originate in his temperament making it manageable or not. Finally, a defensive responding score (DR) and the global stress index can be calculated.

CBCL. structured interview around 8 syndromic scales: anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, somatic complaints, social disorders, disturbances of thought, disturbances of attention, behaviour of transgression of rules, aggressive behavior, which are grouped in other two general dimensions: internalizing and externalizing disturbances. The 2001 version enables therefore to rate the behavior through scales, that partially replicate the diagnostic criteria of the DSM 5, and that in the Italian standardization used are structured in: affective disorders, anxiety disorders, somatic disorders, attention and hyperactivity disorders, oppositional disorders - provokers and disturbances of conduct.

After confirming the diagnosis (K- SADS- PL DSM 5 and CBCL) and collecting information on reflexive functions and parental stress (PSI/SF and RFQ), we started the parent training for parents: it is intended to improve the relationship between parents and children, to increase the capacity to analyse educational problems that may arise, to increase knowledge of the psychological development of children and the principles that govern it, disseminate effective educational methods and make family life and educational problems that can arise more easily manageable [25]. Parent training demands to change relational styles and attitudes that have been adversely affecting children’s behaviour: parents learn to deal effectively with many common problems that, in the long run, can compromise not only the wellbeing of the whole family but the psychological development of the child [26]. The intervention lasted six months, four times a month for a total of 24 meetings. The sample of 60 families has been divided into two sub-groups of 30 according to the model of parent training used to support parental couples. In particular, group 1 performed a parent training based on the Circle of Security, an experiential psychological intervention to support parenthood, where parents are instructed directly by a therapist on how to improve their relationship with their child: increasing degrees of relational safety of children with their parental figures, will affect their self-esteem and will eventually result in a better regulation of their emotional states in various contexts of life. Group 2 has carried out parent training based on the REBT protocol, which is aimed at stimulating cognitive functions, especially those of understanding, interpretation and recognition of emotions. This work makes it possible to model bias and cognitive distortions by eliminating irrational thoughts and promoting better decoding of emotional experience [20]. At the end of the six months of treatment, we reviewed the PSI/SF and RFQ questionnaires to the mothers and the CBCL questionnaire to the only teachers of children of both groups individually, to detect any improvement after treatment, because the enhancement of the parental RF could alter the results of the CBCL when administered to them.

Results

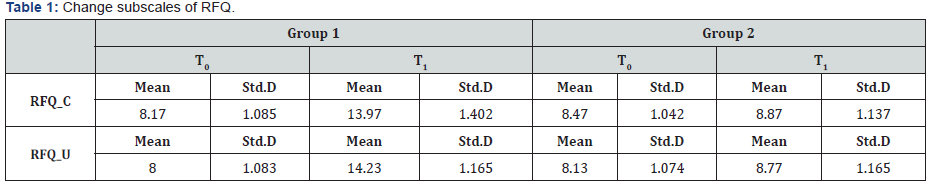

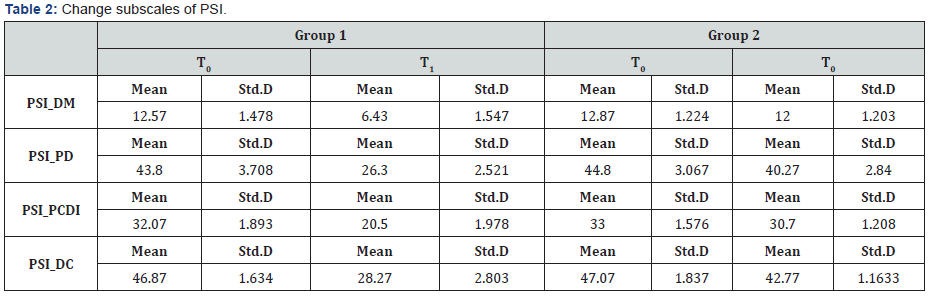

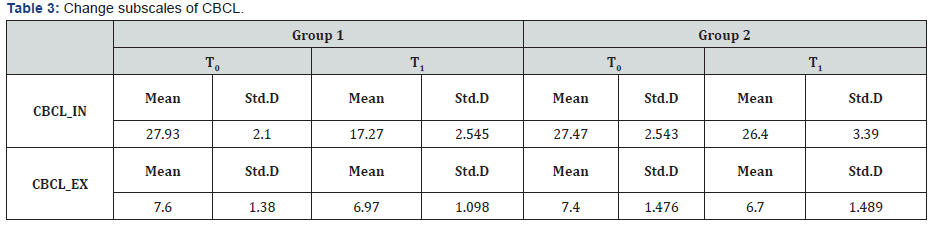

Data analysis has been performed using SPSS 25.0 statistical survey software. Significance has been accepted at a level of 5% (α<0.05). Comparison of groups averages has been made by means of a variance analysis test (Analysis of variance - ANOVA), a parametric test that allows to examine two or more data groups by comparing the variability within these groups with the variability between groups. This analys normally applies distributed test variables suchas Fisher’s random variable F. In this study, we performed an ANOVA to compare scores to individual tests before and after treatment within the same group. Specifically, for Group 1 we compared the RFQ scores before and after the parent training, and significant results were found both in the subscale Certainty [F (1.59) = 321.14; p<0.05] and in the subscale Uncertainty [F (1,59) = 460,74; p<0.05] after treatment, demonstrating that the intervention improves the perception of self that parents have, and that will influence the child’s behaviour in a positive way; we compared the scores from the PSI/SF test before and after the intervention of PT, and significant results were found at subscale PD (parental distress) [F (1.59) = 456.93; p<0.05], at the P- CDI (Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction) [F (1,59) = 535,47; p<0.05] and DC (Difficult Child) [F (1,59)= 985,75; p<0.05] after treatment, demonstrating that PT reduces parental stress perception, improves relationship with the child, which becomes more responsive and improves behavioural aspects. These results have significantly influenced parental responses in reporting a more favorable self-image, made evident by the increased significance to the DR value [F(1.59)=662.52; p<0.05] after treatment; finally we compared the scores of the CBCL before and after the intervention of PT, and meaningful results were found for the externalizing disorders [F(1.59)=313.51; p<0.05] after PT treatment, demonstrating that externalizing symptoms in children with this disorder are reduced compared to the start of treatment (test results fall below clinical relevance). As far as group 2 is concerned, we compared the RFQ scores before and after the parent training, and the scores in the subscale Certainty are not significant, while those in the subscale Uncertainty are slightly below the accepted significance [F(1,59) = 4,791; p<0.05] showing that parental reflexive function while having a slight change after treatment, does not improve significantly; we compared the scores from the PSI/SF test before and after the intervention of PT, and meaningful results were found at subscale PD (parental distress) [F( 1.59) = 651.406; p<0.05], at the P- CDI (parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction) [F(1,59)=40,265; p<0.05] and DC (difficult Child) [F(1,59) = 91,799; p<0.05] after treatment, demonstrating that behavioural cognitive PT however improves the sense of educational effectiveness but not parental reflexive function; finally we compared the scores emerged from the CBCL before and after the intervention of PT and no significant results emerged: this shows that only the improvement of the educational perception does not produce significant results on the change of the child. We then performed an ANOVA in order to compare the scores to the individual tests between the two groups before and after the intervention of PT and to understand which of the two interventions could better improve the perception of parenthood and have a positive effect on the reduction of external symptoms typical of the ODD. We compared the RFQ scores after the parent training intervention in the two groups and found significant results in the uncertainty and certainty subscales that showed a significantly greater improvement in Group 1. We then compared the scores of the PSI/SF test after the intervention of PT in the two groups, and significant results were found at subset PD (parental distress) [F (1.59) = 405.840; p<0.05], PCDI (Parent Child Dysfunctional Interaction) [F (1.59) = 580.968; p<0.05] and DC (difficult Child) [F (1.59) = 599.271; p<0.05] and we found a more meaningful enhancement in group 1 after treatment. Finally, as regards the comparison of CBCL scores, the results show a significant reduction in symptomatology to children in group 1 families (Tables 1-3).

Discussion

This study aims to demonstrate how by improving selfperception and promoting informed parenthood a more competent emotional development in children can be installed. From our analysis an enhancement of reflective functions to subscales of certainty and uncertainty on perception of mental states of self and of others of RFQ test has emerged, after development of parent training in group 1, that is the one in which an intervention focused on the safety circle has been performed, the purpose of which has been reflected in the improvement of the parental regulative and reflective function. High levels of RF in fact can ensure progresses in regulation of affections, development and maintenance of a strong sense of self, as well as constructive social interactions in children, as stated by Fonagy [27]. In group 2, that is, the one in which an intervention focused on emotional rational education was performed, there was no improvement in the reflexive function of the parenthood. With regard to scores from administration of the PSI/SF to mothers of children, there is a significant reduction in the PD (parental distress) and PCDI (parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction) subset after parent training, which shows a major impact in reduction of the child’s difficulties in DC subset, particularly in Group 1. All these findings highlight how maternal containment capacity is indeed a metacognitive competence, which makes the mother capable of perceiving her child as a mental subject and restoring, through functional interactions, an image of self as a mind-endowed subject. The systematic lack of such ability by the caregiver, along with situations of uneasiness and evolutionary risk, would lead to failure in the child’s development of mentalization [27,28]. The detection of the reduction of these indices allows us to say that both types of parent training promote an enhancement in the ability of parents to reflect comprehensively on the inner experience of children, But more relevant results are obtained with the intervention based on the safety circle, working on parental reflexive functions. If the parents are not able to respond adequately, they deny the child a central psychological structure essential to build a stable sense of self [29]. The reflective function (RF) is an evolutionary acquisition that allows the child to respond not only to other people’ behavior, but also to his conception of their feelings, beliefs and expectations. By attributing mental states, a child is able to make all the aforementioned expressions meaningful and predictable, to exhibit a more appropriate behaviour and consequently to respond adaptively to the various interpersonal exchanges. A reason for that also relies in the various self-other representational models, built on the basis of previous relational experiences [29]. In addition, Fonagy [27] defines the capacity of maternal containment as a meta-cognitive competence, which makes a mother able to conceive her child as a mental subject, and to restore through interactions, an image of self as a mind-endowed subject. The systematic lack of such ability by the caregiver, along with conditions of uneasiness and evolutionary risk, might prevent a child from strengthening his mentalization skills [27,28]. Parents who fail to reflect comprehensively on the inner experience of their children, not managing to provide an adequate response, won’t grant them a central psychological structure, which is essential to build an authentic sense of self. According to Fonagy, the determining factor is the ability of a mother to mentally contain and reciprocate her child [30]. Fonagy [29] considers first relational environment as fundamental; he argues that security of attachment to the mother is a competitive predictive index of child’s reflexive capacity. The absence of a reflective function seems to be strongly linked to failure of parental reflex function and to a dysfunction of the family relational system [31]. In this scenario, the child won’t be allowed to create a reflective self and might, as a consequence, display behaviors of avoidance and aggression [32]. Finally, we analyzed the scores on the CBCL test, given to teachers: from the statistical analysis, we have found a significant reduction in scores of the CBCL in the subscale externalizing in group 1, that is the one which had carried out the parent training, according to the Circle of Safety, aimed at increasing the degree of relational safety of children with their parental figures and claims to act also on their self-esteem. In group 2 instead, the scores have not evidenced meaningful results noting therefore that the externalizing symptomatology persists without obvious improvements. From the results of this study one can assert that the lack of reflective function in children seems to be strongly linked to failure of the parental reflexive function and dysfunction of the family relational system [31].

In these cases, the child won’t be able to create a reflexive Self and, as a consequence, could display behaviors of avoidance and aggressiveness [32] typical of the external symptoms of the ODD. Mentalization and good emotional regulation are evolutionary acquisitions that allow the child to respond not only to behavior of others, but also to his own conception of feelings, beliefs and expectations. By attributing mental states, a child can make behaviour of others meaningful and predictable and adjust his own behaviour, so as to be able to respond adaptively to the various interpersonal exchanges. In conclusion, the treatment of behavioural parent training with parents of preschool children, can improve regulative and reflexive child function, providing functional support to the young generations and ensuring adaptive functioning in various life contexts.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Acknowledgment

We are Grateful to the FINDS Neuropsychiatry Clinics all the colleagues who contributed in preparing the data file, including Drs. Vignola Rosanna and Caruso Gabriella, among others.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all caregivers of the participants included in the study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2014) Massimo Biondi (a cura di), DSM-5. Manuale diagnostico e statistico dei disturbi mentali, Milano, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Italy.

- Brazelton BT (1990) Crying and Colic. Infant Mental Health Journal 11(4).

- Kazdin AE (1997) Practitioner review: psychosocial treatments for conduct disorder in children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38: 161-178.

- Bates JE, Bayles K, Bennett DS, Ridge B, Brown MM (1991) Origins of externalizing behavior problems at eight years of In: DJ Pepler, KH Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, United States, pp. 93-120.

- Bearss K, Eyberg SM, Hoza JA (2002) The parenting alliance in divorcing families: Its relation to child adjustment. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Campbell SB (1998) Developmental perspectives. In: T Ollendick, M Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of child psychopathology (3rd edn), Plenum Press, New York USA, pp. 3-35.

- Farruggia R, Romani M, Bartolomeo S (2008) Disturbi della Condotta/Disturbi della Personalità: riflessioni teorico-cliniche per una presa in carico precoce. Psichiatria dell’Infanzia e dell’Adolescenza 75(3-4): 503-513.

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Giovannelli J (2000) Aggressive Behavior In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. Guilford Press, New York, USA, 2: 397-411.

- McBurnett K, Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Loeber R (2000) Low salivary cortisol and persistent aggression in boys referred for disruptive behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry 57: 38-43.

- Giancola PR (2000) Temperament and antisocial behavior in preadolescent boys with or without a family history of a substance use Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 14: 56-68.

- Nelson WM, Finch AJ (2000) Managing anger in youth: a cognitive- behavioral intervention In: Kendall PC (ed.) Child and adolescent therapy: cognitive-behavioral procedures, Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Kendall PC (2000) Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-Behavioral Procedures. Guilford, New York, USA.

- Jenkins AL, McCloskey MS, Kulper D, Berman ME, Coccaro EF (2014) Self-harm behavior among individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and personality disorders. J Psychiatr Res 60: 125-131.

- Linehan MM (1993) Cognitive-Behavioural Treatment of Borderline Personality Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, et al. (1996) The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology 996(8): 141-162.

- Rydell AM, Thorell L B, Bohlin G (2003) Emotionality, Emotion Regulation, and Adaptation Among 5-to 8-Year-Old Emotion 3(1): 30-47.

- Rydell AM, Thorell L B, Bohlin G (2007) Emotion regulation in relation to social functioning: An investigation of child self-reports. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 4(3): 293-313.

- Fonagy P, Steel M, Steel H, Target M (1998) Reflective-Functioning. Manual Version 5, University College London, United Kingdom.

- Fonagy P, Luyten P, Moulton-Perkins A, Lee YW, Warren F, et (2016) Sviluppo e validazione di una misura self-report di mentalizzazione: il Questionario sul funzionamento riflessivo. Plos One 11(7): e0158678.

- Ellis A (1995) Changing rational-emotive therapy (RET) to rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT). Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 13(2): 85-89.

- Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin R, Powell B (2006) The Circle of Security Intervention: Differential Diagnosis and Differential Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 74(6): 1017-1026.

- Abidin RR (1990) Parenting Stress Index/Short Form. Test Manual, University of Virginia, US State.

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Rao U, Ryan N (2019) K-SADS-PL DSM-5, Intervista diagnostica per la valutazione dei disturbi psicopatologici in bambini e adolescenti.

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & Burlington: Research Centre for Children, Youth and Families, University of Vermont, US State.

- Soresi S (2007) Psicologia delle disabilità, Il Mulino.

- Benedetto L (2005) Il parent training: counseling e formazione per i genitori, Carocci, Italy.

- Fonagy P (2002) Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the New York: Other Press; xiii, 577.

- Frolli A, La Penna I, Cavallaro A, Ricci MC (2019) Theory of Mind: Autism and Typical Acad J Ped Neonatol 8(4): 555799.

- Fonagy P, Target M (2001) Attaccamento e funzione riflessiva: il loro ruolo nell’organizzazione del Sé. In: Fonagy P, Target M Attaccamento e funzione riflessiva, Raffaello Cortina, Milano, pp. 101-133.

- Ammaniti M, Dazzi N (1999) Attaccamento e processi di Psicologia Clinica dello sviluppo anno 3(1): 101-107.

- Baldoni F (2008) Alle origini del trauma: confusione delle lingue e fallimento della funzione riflessiva. In: Crocetti G, Zarri A (a cura di), Gli dei della notte sulle sorgenti della Il trauma precoce dalla coppia madre al bambino, Pendragon, Bologna, Italy, pp.137-159.

- Concato G (2006) Manuale di psicologia dinamica. AlefBet, Firenze, Italy.