How Oxytocin Modulates Distress and Support-Seeking in Adolescence According to Attachment Style? An Exploratory Eye-Tracking and Neurophysiological Study

Monika Szymanska, Julie Monnin, Grégory Tio, Chrystelle Vidal, Lucie Galdon, Carmela Chateau Smith, Sylvie Nezelof and Lauriane Vulliez-Coady*

University of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, France

Submission: January 27, 2020; Published: February 12, 2020

*Corresponding author: Lauriane Vulliez-Coady, Associate Professor, University of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, University Hospital of Besançon, France

How to cite this article:Monika S, Lauriane V-C, Julie M, Grégory T, Chrystelle V, et al. How Oxytocin Modulates Distress and Support-Seeking in Adolescence According to Attachment Style? An Exploratory Eye-Tracking and Neurophysiological Study. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2020; 14(3): 555887. DOI:10.19080/PBSIJ.2020.14.555887.

Abstract

Insecure attachment is a potential factor of emotional dysregulation in adolescence. This raises the question of whether administering intranasal oxytocin (INOT), the paradigmatic “attachment hormone”, may be beneficial on attachment-related emotion regulation (ER). This exploratory study investigates the effects of INOT administration on ER in adolescents, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Adolescent attachment style was determined by Attachment Style Interview. Twenty-five insecure male adolescents received 16 IU or 24 IU of INOT or placebo. Forty-five minutes later, gaze parameters and skin conductance reactivity (SCR) were recorded, in response to pictures of distress, and then to pictures of comfort, joy-complicity, and neutral states. INOT significantly increase SCR latency when viewing pictures of distress. During the “comfort-seeking” phase, glance count increased significantly for both comfort and neutral pictures. The results of this pilot study indicate that a single dose of INOT is sufficient to influence attachment-related ER in distressed insecure adolescents.

Keywords: Intranasal oxytocin; Attachment; Emotions; Insecure; Adolescents

Abbrevations: OT: Oxytocin; INOT: Intranasal Oxytocin; ER: Emotion Regulation; SCR: Skin Conductance Reactivity; HRP: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal.

Introduction

There is a growing literature about oxytocin (OT), the paradigmatic “attachment hormone” that represents the biological aspect of attachment [1]. Oxytocin, a hypothalamic neuropeptide, acting both as a neuromodulator in the central nervous system and as a hormone in the periphery [2] appears more and more to be a potential preventive intervention or aid in psychiatric treatment, due to its prosocial effects [3]. It is a key molecule implicated in the regulation of several reproductive and social functions; for example, administering exogenous OT via a nasal spray increases trust and empathy [4,5]. Few studies have explored how oxytocin influences attachment behaviors and representations, although attachment is among the factors influencing the effectiveness of emotion regulation (ER) [6].

Attachment is an innate psychobiological behavioral system, activated in times of perceived distress [7] inciting children to seek proximity and comfort from their attachment figures [8,9]. The system is deactivated once a perceived sense of security and safety is reestablished. The quality of early attachment interactions with an attachment figure leaves an enduring mark on the developing person: attachment representation (secure or insecure; withdrawn or anxious) is likely to be associated with the way stress is perceived and dealt with across the lifespan [10-12]. Individuals with secure attachment have successfully mastered the process of seeking proximity to others for relief from distress, leading to a capacity to experience, express, and tolerate temporally distressing events. When attachment security is not attained, the use of alternative, insecure attachment strategies of avoidance or anxiety may be triggered. Insecure withdrawn adolescents tend to suppress emotional expression and comfort-seeking strategies [13]. Insecure anxious adolescents, who tend to fear rejection and separation, express a greater desire for company, and present cortisol dysregulation secretion [14].

These studies, among others, show that insecure attachment is a potential factor of emotional dysregulation and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and adulthood [15,16]. Prior research indicates that intranasal oxytocin (INOT) yields different effects depending upon the participant’s attachment security, in randomized controlled studies (INOT versus placebo, PB) among adult populations [17]. Other effects of INOT on stress reactivity have been found. The conjunction of INOT administration and of social support from best friends had a psychosocial stress-buffering effect on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activation [18] among 37 healthy men exposed to the Trier Social Stress Test. Similarly, INOT reduced skin conductance response (SCR) in relation to fear-associated stimuli [19]. To date, only one study has explored INOT response in adolescents (healthy controls versus inpatients) regarding attachment-related trust [20]. There, INOT was found to increase the level of trust of inpatients to a “healthy control level” in a trust game over internet with their mother and a stranger. Among healthy adolescents, attachment security moderated the effects of INOT.

Together, these studies provide indications that a single dose of INOT can affect attachment representation, behavior, and physiological responses in humans. However, despite the importance of INOT treatment outcomes in attachment and socio-emotional contexts, the effects of OT on social support-seeking under stress in insecure adolescents are still insufficiently studied. To extend this line of work, this pilot study investigated the effects of a single dose of INOT on insecure male adolescents, through a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, as part of a larger ER study [21,22].

In this study, we employed a distress-then-comfort-seeking paradigm divided into two phases. First, the adolescent’s attachment system was activated by the visualization of pictures of distress. Second, to determine how adolescents deactivate their attachment system, three pictures were presented simultaneously (comfort, joy-complicity, and neutral), corresponding to the phase of comfort-seeking. A multimodal approach (gaze parameters and SCR) was used to objectively assess INOT effects on this dynamic attachment-related ER. We hypothesized that INOT would modify behavioral and/or physiological reactions of insecure adolescents toward more secure strategies. During distress exposure, INOT should reduce stress reactivity and insecure strategies. During the support-seeking phase, INOT should enhance support-seeking toward comfort pictures.

Materials and Method

Participants

As part of a bigger study among 81 adolescents recruited in secondary schools in Besançon, France, twenty-five insecure male volunteers participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-treatment-with-INOT, randomized trial. A group of secure male volunteers (N=12), who participated in the study without treatment, was used as a reference group [22]. The reference group was concomitant with the study groups but was not randomized. It was used to estimate and characterize values in secure patients. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Exclusion criteria were medical or psychiatric illness, use of medication, substance abuse, or smoking (more than 20 cigarettes a day). Participants were instructed to abstain from food and caffeine-based drinks for 2 hours before INOT administration. An informed consent form was signed by the participants, and their parents (for minors). An open-loop gift card with a value of 20 € was given to each adolescent for participation. The study was approved by the French Agency for the Safety of Health Products and the local ethics committee, and registered in the Clinical Trials Register (NCT02301715).

Study procedures

Two visits were necessary for the assessment protocol. During the first visit, participants were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria by a psychiatrist; their psychiatric and attachment profiles were also assessed. During the second visit, an eye-tracking task combined with SCR measurement was performed 45 min after the treatment with INOT or PB. For more details, see the previously published study protocol [21].

Attachment assessment

All eligible participants responded to the Attachment Style Interview [23], in order to determine their attachment style. The ASI is a semi-structured interview, validated in French, and adapted for use with adolescents. It assesses attachment style, based on the ability to make and maintain supportive relationships with one parent and two “very close others”, who can be friends or family members. Attitudes about closeness to/distance from others, autonomy, and fear/anger in relationships were also assessed. Overall attachment style was categorized in terms of secure attachment or insecure attachment, the latter comprising the standard typologies of anxious and withdrawn. When two profiles of insecurity were found, the attachment style was coded dual. In order to control for individual psychometric dimensions, several psychometric questionnaires were used, including the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [24], the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety (STAI-YA, STAI-YB) [25], and the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20 (TAS-20) [26].

Treatment

Each participant received either an active INOT (Novartis, Austria) (N = 12) or PB (N = 13) spray. Age-dependent dosage was employed: younger participants (aged 13 to 15) received 16 international units (IU), and older participants (aged 16 to 20) received 24 IU [27]. The placebo was custom-designed by the hospital pharmacy to match drug minus the active ingredient. Either INOT or PB was administered to each participant, 45 minutes before the experimental phase, which took place between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m., to take into account diurnal OT variation.

Pictures

The visual stimuli consisted of pictures from the Besancon Affective Picture Set-Adolescents (BAPS-Ado) [28], representing distress, comfort, joy-complicity, and a neutral state. Pictures of distress represented faces expressing sadness, anguish, or scenes of loss and separation. Comfort pictures represented scenarios of a parent comforting an infant or an adolescent after an episode of distress. Pictures of joy-complicity represented joyful moments. Finally, neutral scenes represented persons in the distance, walking along a street, or in the subway. The picture sequences were organized to “activate” and “deactivate” the attachment system. During the activation phase, a distress picture (N = 20) was presented for 10 sec. During the deactivation phase, 3 pictures (comfort N = 20, joy-complicity N = 20, and neutral N = 20) were presented together for 20 sec.

Eye-tracking measurement

Eye movements were recorded using the Remote Eye-Tracking Device (RED 500, Senso Motoric Instruments, SMI, Teltow, Germany) at a rate of 250 Hz. Details relating to the apparatus can be found in the previously published protocol [21]. Prior to detailed statistical analysis, the whole of each picture was treated as a single area of interest (AOI) for the 4 categories: distress, comfort, joy-complicity, and neutral. A gaze fixation should last for 80 ms on a surface of 100 pixels to be classified as a fixation [29]. When a single distress picture was presented, dwell time, which corresponds to the time that the gaze was within the distress picture, was measured. The mean of dwell time percentage, expressed as a percentage of the total duration of a trial, was determined as follows: dwell time (ms) / (end time - start time). It represents the salience or visual attractive power of the picture and reflects engagement patterns.

When three pictures were presented together (comfort, joy-complicity, and neutral), two other variables were measured: glance count and entry time (ms). Glance count corresponds to the number of glances at a target within a certain period, with saccades coming from outside. It was calculated by averaging all glances inside the AOI per trial. It reflects attentional focus. Entry time (ms) corresponds to the average time from stimulus onset to the first fixation on the AOI, in milliseconds per trial [29]. This parameter reflects the time needed to detect emotional visual stimuli and indicates the first gaze orientation toward each of the three pictures [30].

Neurophysiological measurement

The SCR was recorded using Biopac© MP 36 (Biopac © Systems, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). A pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes filled with isotonic electrode gel was attached to the distal phalanges of digits II and III on the non-dominant hand. The 3-minute baseline responses were recorded, with the BIOPAC system, without stimuli. The neurophysiological monitoring AcqKnowledge 4.3 software was synchronized with Experiment Center 3.0 software by event markers representing the beginning of each picture. The AcqKnowledge application was used to extract latency, amplitude of skin conductance responses (SCR), and skin conductance level. The SCR was defined as the maximum change in conductance (μSiemens) in the 0.1 to 6-second window after stimulus onset.

Intranasal oxytocin administration side-effects

We used questionnaires to detect any side-effects of INOT administration. All adolescents were asked whether they had experienced the most commonly reported side-effects immediately after the task, and then 30 days later, when adolescents answered the same questions by phone interview.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To investigate the effects of INOT on the variables studied, a Wilcoxon test was used. Continuous variables are represented as: (Median [Q1; Q3]). Effects are considered significant if the p-value is below .05 for dwell time and SCR latency for distress pictures, and for glance count (Gaze parameters) for each picture category during the support-seeking phase. Exploratory secondary analyses will be performed with an adjusted level of statistical significance of .001 (for multiple criteria: entry time, dwell time, SCR amplitude, etc. and different picture categories). The statistical analysis was only performed between INOT and PB groups. Data from the reference group were used in a descriptive analysis, and no statistical comparison was performed with this group.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Data were first analyzed for outliers. Outliers for each eye-tracking variable were deleted from the analyses, using z-score with a mean threshold of +/- 3.29. After threshold application, almost all data were kept (99.9%).

Population characteristics

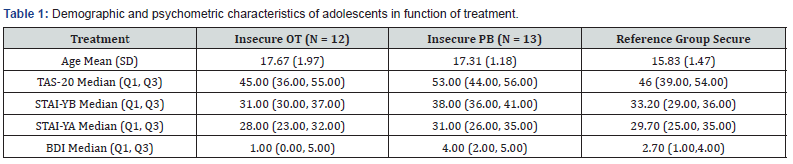

The study population was composed of 25 insecure male adolescents and 12 secure male adolescents. Both groups presented similar psychological dimensions (see Table 1 for population characteristics).

Distress exposure

Effect of INOT on gaze parameters

Intranasal OT tended to reduce dwell time percentage for distress pictures [(W(1) = 3.4201, p = 0.0644); PB (92.25 [88.08; 94.99]) INOT (87.05 [80.26; 89.80])].

Effect of INOT on neurophysiological parameters

At a physiological level, it was hypothesized that INOT would attenuate neurophysiological arousal in response to distress pictures. As expected, the Wilcoxon test indicated a significant main effect of INOT on SCR latency (sec) (W(1) = 4.2722, p = 0.0387). Intranasal OT increased SCR latency (sec) (2.68 [2.40; 2.87]) compared to PB (2.43 [2.23; 2.49]). For the reference group, SCR latency (sec) was 2.33 (2.24; 3.12).

Intranasal OT did not influence SCR amplitude.

Support-seeking phase

Effect of INOT on gaze parameters

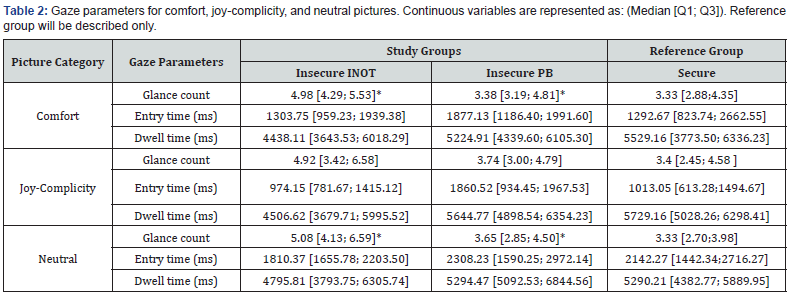

Following our hypothesis, INOT should enhance comfort-seeking. The Wilcoxon test indicated a significant main effect of INOT on increasing glance count for comfort (W(1) = 4.8565, p = 0.027) and for neutral W(1) = 4.502 ; p = 0.0339. Other comparisons were not significant with an adjusted alpha level (Table 2).

Significant statistical difference between the 2 study groups (p-value<0.05 for glance count on each picture categories or p-value <0.001 for secondary criteria

Discussion

This pilot study examined the effects of INOT versus PB on emotion regulation (ER) in 25 insecure male adolescents (12 INOT, 13 PB) under conditions of a distress-then-comfort-seeking paradigm. During the first phase, “distress exposure”, our results indicate that a single dose of INOT tended to reduce dwell time on distress pictures and decreased physiological arousal in response to them. This result might suggest that INOT reduces engagement patterns on distress, and thus reduces the stress in response to distress. This behavior is supported by two studies on adult populations: one study indicating that INOT decreased eye contact in response to negative facial expressions [31], and another indicating that INOT decreased amygdala activity and cortisol secretion in response to negative emotional stimuli [18,32].

An important question in our study was the effect of INOT on comfort-seeking in insecure adolescents. As expected, insecure adolescents explored comfort pictures more under INOT than PB. This effect is corroborated by previous research highlighting the role of INOT in social support-seeking in distressed women [33]. Nevertheless, little is known about the effects of INOT on more specific attachment processes, such as support-seeking, among insecurely attached people [34,35]. In our study, we differentiate comfort from joy-complicity. Interestingly, the effect of INOT on glance count was only significant for comfort pictures. During this support-seeking phase, another hypothesis of the study was that INOT would increase the feeling of security, and allow insecure adolescents to process equally not only attachment-related, but also non-attachment-related information (i.e. neutral pictures) as secure adolescents do [22]. Our results indicate that INOT enhanced glance count for comfort and neutral pictures in insecure adolescents compared to PB. In our previous study using the same paradigm, secure adolescents displayed a similar pattern: exploring first the comfort and joy-complicity pictures, and then exploring the neutral pictures, which contain more details (e.g. streets and subways) [22]. In agreement with other studies suggesting that the exploratory system is optimal only when the attachment system is deactivated, and when the adolescent is soothed [7,36], our study suggests that insecure adolescents felt more secure to explore non-attachment-related information [6,8,37].

Despite the robustness of a multi-level approach, several limitations to our pilot study deserve consideration. The size of our sample does not allow us to comment on the generalization of our results. Future work is needed to determine INOT effects on emotion regulation in insecure adolescents in relation to attachment style, especially as the literature shows that the styles of insecure attachment [20], and its intensity [12,35,38-40], can both influence OT effects. We did not include females in this study as we were not able to control for pregnancy risk. This limitation is general in the literature.

Conclusion

Insecure attachment is a potential factor of emotional dysregulation and the development of psychopathology in adolescence. Oxytocin, the paradigmatic “attachment hormone”, could potentially promote social bonding, and social support-seeking under stress. Our pilot study is one of the first double-blind randomized controlled trials to examine INOT effects on ER in insecure adolescents, in the specific context of attachment. Our findings show that INOT reduced neurophysiological arousal to distress, and increased comfort-seeking and exploration. We found that INOT produced no consistent side-effects or adverse outcomes, at single doses of 16-24 IU, assessed at two time points: about 90 min after nasal spray administration, and 30 days after administration. Future research could consider using INOT on a larger sample, over a longer period, and in different contexts, as INOT may have a nuanced range of effects that depend not only on attachment style but also on contextual factors.

References

- Feldman R, Gordon I, Schneiderman I, Weisman O, Zagoory-Sharon O (2010) Natural variations in maternal and paternal care are associated with systematic changes in oxytocin following parent-infant contact. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35: 1133-1141.

- Carter CS (2014) Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Annu Rev Psychol 65: 17-39.

- Szymanska M, Schneider M, Chateau Smith C, Nezelof S, Vulliez-Coady L (2017) Psychophysiological effects of oxytocin on parent-child interactions: A literature review on oxytocin and parent-child interactions. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 71: 690-705.

- Abu-Akel A, Fischer-Shofty M, Levkovitz Y, Decety J, Shamay-Tsoory S (2014) The role of oxytocin in empathy to the pain of conflictual out-group members among patients with schizophrenia. Psychological medicine 44: 3523-3532.

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Abu-Akel A, Palgi S, Sulieman R, Fischer-Shofty M, et al. (2013) Giving peace a chance: Oxytocin increases empathy to pain in the context of the israeli-palestinian conflict. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 3139-3144.

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2007) Attachment processes and emotion regulation. In: Mikulincer M, Shave PR (Eds.), Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The guilford Press, New York, United States, pp. 190.

- Bowlby J (1969) Attachment and loss. Basic Books, New York, USA.

- Ainsworth MD (1991) Attachment and other affectional bonds across the life cycle. In: Parkers J, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P (Eds.), Attachment across the life cycle. Routledge, United Kingdom, pp. 33-51.

- Ainsworth MD (1985) Patterns of infant-mother attachments: Antecedents and effects on development. Bull N Y Acad Med 61: 771-791.

- Kobak RR, Sceery A (1988) Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation, and representations of self and others. Child Dev 59: 135-146.

- Mikulincer M, Dolev T, Shaver PR (2004) Attachment-related strategies during thought suppression: Ironic rebounds and vulnerable self-representations. J Pers Soc Psychol 87: 940-956.

- Bartz JA, Lydon JE, Kolevzon A, Zaki J, Hollander E, et al. (2015) Differential effects of oxytocin on agency and communion for anxiously and avoidantly attached individuals. Psychol Sci 26: 1177-1186.

- Beijersbergen MD, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Juffer F (2008) Stress regulation in adolescents: Physiological reactivity during the adult attachment interview and conflict interaction. Child Dev 79: 1707-1720.

- Oskis A, Loveday C, Hucklebridge F, Thorn L, Clow A (2011) Anxious attachment style and salivary cortisol dysregulation in healthy female children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52: 111-118.

- Lyons-Ruth K, Choi-Kain L, Pechtel P, Bertha E, Gunderson J (2011) Perceived parental protection and cortisol responses among young females with borderline personality disorder and controls. Psychiatry Res 189: 426-432.

- Pascuzzo K, Cyr C, Moss E (2013) Longitudinal association between adolescent attachment, adult romantic attachment, and emotion regulation strategies. Attach Hum Dev 15: 83-103.

- Buchheim A, Heinrichs M, George C, Pokorny D, Koops E, et al. (2009) Oxytocin enhances the experience of attachment security. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34: 1417-1422.

- Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U (2003) Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry 54: 1389-1398.

- Eckstein M, Becker B, Scheele D, Scholz C, Preckel K, et al. (2015) Oxytocin facilitates the extinction of conditioned fear in humans. Biol Psychiatry 78: 194-202.

- Venta A, Ha C, Vanwoerden S, Newlin E, Strathearn L, et al. (2017) Paradoxical effects of intranasal oxytocin on trust in inpatient and community adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 1-10.

- Szymanska M, Chateau Smith C, Monnin J, Andrieu P, Girard F, et al. (2016) Effects of intranasal oxytocin on emotion regulation in insecure adolescents: Study protocol for a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 5: e206.

- Szymanska M, Monnin J, Tio G, Vidal C, Girard F, et al. (2019) How do adolescents regulate distress according to attachment style? A combined eye-tracking and neurophysiological approach. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 89: 39-47.

- Bifulco A (2008) The attachment style interview (asi): A support-based adult assessment tool for adoption and fostering practice. Adoption & Fostering 32: 33-45.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) Manual for the beck depression inventory-ii.

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA (1983) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, California, United States.

- Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ (1994) The twenty-item toronto alexithymia scale-i. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 38: 23-32.

- Guastella AJ, Howard AL, Dadds MR, Mitchell P, et al. (2009) A randomized controlled trial of intranasal oxytocin as an adjunct to exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34: 917-923.

- Szymanska M, Monnin J, Noiret N, Tio G, Galdon L, et al. (2015) The besancon affective picture set-adolescents (the baps-ado): Development and validation. Psychiatry Res 228: 576-584.

- Holmqvist K, Nyström N, Andersson R, Dewhurst R, Jarodzka H, et al. (2011) Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures.

- Jacob RJK, Karn KS (2003) Commentary on section 4 - eye tracking in human-computer interaction and usability research: Ready to deliver the promises a2 - hyönä, j. In: Radach R & Deubel H (Eds.), The mind's eye. North-Holland, Europe, pp. 573-605.

- Domes G, Steiner A, Porges SW, Heinrichs M (2012) Oxytocin differentially modulates eye gaze to naturalistic social signals of happiness and anger. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 1198-1202.

- Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (2008) Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron 58: 639-650.

- Cardoso C, Valkanas H, Serravalle L, Ellenbogen MA (2016) Oxytocin and social context moderate social support seeking in women during negative memory recall. Psychoneuroendocrinology 70: 63-69.

- Buchheim A, Heinrichs M, George C, Pokorny D, Koops E, et al. (2009b) Oxytocin enhances the experience of attachment security. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34: 1417-1422.

- De Dreu CKW (2012) Oxytocin modulates the link between adult attachment and cooperation through reduced betrayal aversion. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37: 871-880.

- Bowlby J (1982) Attachment and loss. (2nd edn), Basic Books, New York, USA.

- Biro S, Alink LR, Huffmeijer R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IMH (2015) Attachment and maternal sensitivity are related to infants' monitoring of animated social interactions. Brain Behav 5: e00410.

- Bartz JA, Zaki J, Ochsner KN, Bolger N, Kolevzon A, et al. (2010) Effects of oxytocin on recollections of maternal care and closeness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 21371-21375.

- Fang A, Hoge EA, Heinrichs M, Hofmann SG (2014) Attachment style moderates the effects of oxytocin on social behaviors and cognitions during social rejection: Applying a research domain criteria framework to social anxiety. Clin Psychol Sci 2: 740-747.

- Parrigon KS, Kerns KA, Abtahi MM, Koehn A (2015) Attachment and emotion in middle childhood and adolescence. Psychological Topics 24: 27-50.