Enacted Narrative and Recovery: An Existential Analysis Based on Hermeneutic-Phenomenological Interpretation

Jan Sitvast*

Lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences Hogeschool Utrecht, The Netherlands

Submission: August 13, 2019; Published: September 12, 2019

*Corresponding author: Jan Sitvast, University of Applied Sciences HU, Faculty of Health, Team: Master of Advanced Nursing Practioners (MANP), Heidelberglaan 7, 3584CS Utrecht, The Netherlands

How to cite this article:Jan Sitvast. Enacted Narrative and Recovery: An Existential Analysis Based on Hermeneutic-Phenomenological Interpretation. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 13(2): 555860. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.10.555860.

Keywords

Keywords: Hermeneutics; Recovery-oriented care; Narrative; Hope; Meaning giving

Relevance for Clinical Practice

The hermeneutic-moral model may assist students in nursing in facilitating recovery in mental health care. It highlights the importance of reflection enriched by expression and sharing. The overview of the existential dimensions of how persons experience themselves may create awareness in care professionals of the importance of meaning-making processes. It also creates an outline of how nurses and other professionals in mental health care can facilitate and support service users in the telling of an empowered (recovery) narrative.

Background

As narrative approaches gained momentum in the social sciences in the middle of the last century, some professionals working in the healthcare arena recognized the limitations of rationalist frameworks and sought to introduce similar approaches in health care [1]. Some of the earlier contributors include: Balint [2], Kleinman [3], Brody [4]. Frank [5] identifies three fundamental illness narratives: restitution, chaos and quest. Restitution narratives are those of the person anticipating recovery; chaos narratives are enduring with no respite; quest narratives are those where people discover that they may become transformed by their illness. What is common to all types of illness narratives is the focus upon the centrality of the telling of the patient’s experience. This is for both epistemological and sense-making functions [6]. The epistemological concerns itself with furthering knowledge of a disease from firsthand experience and the sense-making is more to do with making sense of illness, or extracting meaning from the experience, thus infusing hope. Quite recently, Hamkins [7] developed what she referred to as Narrative Psychiatry. Through this, she has claimed to empower patients to shape their lives through story and sees this method of practice as a clinical art form. Holloway & Freshwater [8] took narrative theory and applied the theory to nursing research. Since the turn of the century, published narrative research in nursing has grown exponentially thus securing a strong place in nursing evidence.

Introduction

This article is about recovery-oriented care and the need for a theoretical framework to support this. Key concepts that can be identified as relevant for the development of recovery and social inclusive approaches in mental health care are identity, hope, meaning-giving and empowerment. In order to respect the uniqueness of the individual journey, treating people with dignity, exercising empathy and maintaining an unconditional positive attitude towards the person emotional intelligence is demanded from professionals [9]. What also has become clear is that mental health nursing that claims to be recovery-orientated should consider service users’ narratives to be of foremost importance. Narratives have featured significantly in the international recovery literature and the use of narratives is becoming wide-spread as triggers for reflection and insight into the construction of personal identity [10].’Narrative’ is understood here to have a close affinity with the mental activity with which humans coordinate, explain and legitimize their acts [11-14]. Philosophers such as Ricoeur [15] and MacIntyre [16] claim that people need stories to motivate their actions and present them to others. Narratives are thus vehicles for meaning-making.

As recovery is the ultimate goal, we must first define recovery. William Anthony [17], director of the Boston Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, identified recovery as

“a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by the illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness”(p.15).

In this definition the development of new meaning is closely linked with the experiences in daily life and the values, goals, skills and roles that go with them.

In this article, we focus on personal recovery, that concerns identity and self-image. There is of course also the functional recovery that relates to reduction of illness symptoms and the rehabilitation of psychosocial functioning. We will not go into that here. This means that in this article we do not address mental health problems directly, but for the consequences they have for identity-formation, self-confidence and empowerment.

The process of giving meaning in life seems to be the connecting common element in all domains of personal recovery. This legitimizes the hermeneutic phenomenological approach (based on the work of Heidegger, Ricoeur and Cassirer) in our discussion of personal recovery and how professionals can facilitate or support it. The purpose of the article is to debate how people make meaning from their experiences when tackling the impact on their lives and the consequences of mental health problems [18-22].

As Grant, Leigh-Phippard & Short [23] reported for the UK, the storied complexities of recovery-survival are often neglected in mental health policy. The ‘survival’ aspect of recovery, relates to liberatory struggles of service users against invalidating societal and institutional practices, including those of institutional psychiatry [24-27]. Facing the necessity to make choices when reconstructing their lives service users are sometimes confronted with conflicts in their relation with mental health professionals around contested assumptions about what constitutes legitimate choices. As Grant et al. [23] demonstrated in their study service users can be ‘overwhelmed’ by dominant narratives of local mental health services in the name of treatment and care in ways that ultimately prove damaging to them and at odds with recovery.

Method

The argument in this paper was developed from the focus on identity, hope, meaning-giving and empowerment that Stickley et al. [9] recognized as important for advanced mental health nursing practice. This was done in a discursive way by positing theses, accounting them with research findings and combining them in new ways that are philosophically and otherwise legitimized. The process of meaning-making was looked upon from a hermeneuticphenomenological perspective and a sociological point of view. On the basis of an existential analysis of life’s experiences, the first framework of a hermeneutic-moral model for mental health nurses was drafted. We think that such a model does not yet exist in nursing, although nursing and caring in general have been based on moral notions (e.g. [28,29]) and hermeneutic phenomenological perspectives have been used to explain meaning-making processes in health care (e.g. [30,31]), its combination has been fragmentary. There is a hermeneuticphenomenological research method, especially in holistic nursing [32]. Holistic care aims at enhancing the lifelong discovery of meaning and personal potential for the one caring and the one cared for, Cowling 2000, cited with 32), but here too this scope has not been linked to a hermeneutic-moral model for nursing praxis.

This is similar to, but different from the Tidal Model [33] which seeks to construct a narrative-based form of practice in mental health nursing. The Tidal Model has been developed by Barker et al. in the late 1990’s and today more than 100 sites in hospital, community, rehabilitation and forensic settings throughout the world have been organized on basis of its principles. The narrative focus of the Tidal Model aims to use the experience of the person’s journey and its associated meanings, to explore and plan the ‘next step’ - what needs to be done to help the person make progress on the life journey. “By emphasizing the centrality of the lived-experience, of the person and her/his significant others, the Tidal Model emphasizes the need for mutual understanding between the nurse and the person in care” [34, p.10]. However the model is pragmatic and is in need of theoretical underpinning, as has been identified by other authors (e.g. [35]). The model that will be developed here meets this demand and may therefore assist students in supporting and facilitating recovery in mental health care. We will start by discussing key concepts.

Narrative

Persons with mental health problems often have to cope with a selfimage that lies under attack and they may feel the need to re-story their lives and find a new relation with their problems and difficulties. When accepting a diagnosis with a mental health problem, the ‘psychiatric patient’ identity may negatively impact on a person’s sense of agency, that is: being able to explain his/her intentions without reverting to disease symptoms. A ‘good’ story however restores credibility in one’s owns eyes and those of others. This point is illustrated through numerous anthologies of people using mental health services that have emerged in recent years [27, 36-39]. When someone experiences a vulnerability and faces the challenge to give that vulnerability a place into his/her or her self-image, then a too realistic estimation of deficiencies and impairments because of mental health problems may forestall a hopeful narrative. A hopeful narrative may be wished for more than a narrative true to life [40]. Yanos, Roe and Lysaker [41] found in a literature review that persons accepting a definition of oneself as ‘mentally ill’ and at the same time viewing ‘mental illness’ through a lens of incompetence and inadequacy has led to less hope and diminished self-esteem (when compared with persons who did not self-stigmatized themselves), which resulted in avoidant coping, active social avoidance, depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation.

It is therefore that in the sessions of recovery, peer groups participants learn from each other to (re-) construct their life story to integrate mental health problems in the story without letting it dominate their lives [42]. This is why recovery-oriented care also aims at supporting service users in becoming aware of their values in life. Restorying their lives involves distinguishing important values from the impact of illness symptoms and the stigmatizing influence of treatment in order to reformulate ambitions, wishes and goals that are connected with this deeper and whole core of values. Narrative re-storying can be defined as a personally and relationally transformational method of reflexive inquiry (Richardson 2000, cited by Grant, Leigh-Phippard & Short [23]). It is all about “the re-interpretation and re-narration of lived experiences in line with co-evolving preferred personal and relational identities” (Grant & Zeeman 2012, cited by Grant et al, [23]: pp.280). Re-storying is thus not only a transformational tool but constitutes an informed ethical choice about how best to make sense of one’s past, present, and future life and relationships (Frank [5] cited by Grant et al. [23]) Who you really are as a person, beneath the outward appearances of being someone with a mental health disorder, is what again must be brought to the surface. This is part of an existential analysis of the life story.

Although the main stream of psychiatry (and in its wake mental health nursing) is still very much diagnosis-focused and inclined to identify problems, disorders and symptoms in the patient’s narrative (thus confirming the ‘dominant’ narrative), there are other, more dialogic approaches that do justice to the need for narrative restorying in recovery. There is the approach of ‘narrative psychiatry’ that focuses on seeking the sources of a person’s strength, rather than on finding the root of their problems, [7]. Furthermore, Bracken and Thomas [43] coined the term ‘post psychiatry’, which stands for a context-centered approach that tries to understand the effects of social factors on individual experience. Priority is given to the process of meaning-making and interpretation [43]. What these approaches have in common is their emphasis on the process of meaning-making and the relevance of values. These processes are seen to be bound together by a web of meaningful contexts, social networks, political and cultural realities from which mental phenomena are not separated but, on the contrary, are embedded in. This asks for an existential phenomenological analysis.

An existential analysis

The existential analysis is based on the phenomenology of Cassirer [44,45] of how man gives meaning to reality [46]. This process of giving meaning is mediated by symbols: signs that represent objects or entities in the world. The process of symbolization starts with impressions that come before the objectifying symbolization through language. We can express these impressions: for example in images and sound/ music. This is the pre-discursive intuitive perception: It draws on the collective repertoire of semi-conscious images, as for instance the image of a road that stands for the path every person has to go through in life. These images have a holistic, still unbroken inner coherence that shows us the world as closed and as one whole. The next step in the process of symbolization is the objectifying through verbalization. The world is not any longer given as a whole but becomes ‘articulated’. The world is put at distance and becomes a complex entity of objects that is constituted as such through naming them. It opens the closure of the image for a discursive reflection.

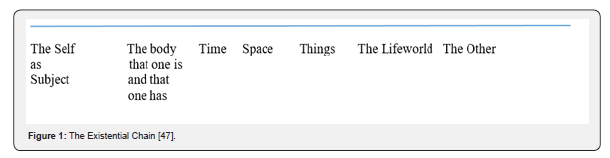

Symbolization concerns how an individual sees himself in relation to others and the world around them. It comprises perspectives on human life and can be studied in an existential and phenomenological analysis as Van der Bruggen [47] did. In his existential analysis perspectives on human life are described in a chain (Figure 1). The starting point is the human individual, the subject, who experiences one’s self as a ‘self’. The aspect of having a body is an integral part of this experience. With his/her body the individual travels through time and place. Man stands in relation to the world around him: nature and artifacts. The life-world of human experience encompasses all this, as well as and even in the first place his living together with other men and women. Meeting the ‘Other’ in the social context may very well be the most fundamental characteristic of human existence.

Let us see how this relates to a person who develops mental health problems. Being “ill” can be seen as a way of existing in which these perspectives may be experienced differently from when one is “healthy”. Service users communicate these perspectives in so called illness narratives (for example as identified by Frank [5]). Illness narratives stand for the lived experience of service users and can be distinguished from disease narratives in which the medical diagnosis holds a central place. An illness narrative can become a recovery narrative in the course of time. Both are interpretations, symbolized from underlying experiences and socially constructed in contact with relevant others. Recovery is about bringing to the surface who you really are as a person, and also that your story, in order to be credible, must enable you to live the story and act upon it. This credibility is very much at stake in social interaction, as we will see now.

The Social construction of the Self

In every social interaction message are given off with information about who you are. That is how self-disclosure is realized: the telling and re-telling of personal experiences [48]. The information that is told is used in two ways, namely, to earn respect and to engage a relationship. One of the social functions of narrative is the keeping of face and the prevention of losing face in interaction (which is not a small thing when you are perceived as ‘mentally ill’ by others). The identity of a person as we come to learn through social interaction is not the expression of a substantial phenomenon (a solidly delimited ‘I’) in the first place, but the result of a local staging (performance, enactment) of more or less flowing qualities and attributes which right there and then make part of a temporary entity that functions as a character in a story. We speak of enacted narratives [16]. This approach links up with schools within narrative psychology, especially the social constructionism, in which the dialogical and relational components in the concept of Self are emphasized. The Self becomes a narrative that must be rendered intelligible in ongoing relationships [12].

Nurses Facilitating the Development of Recovery Narrative

We connect now the existential aspects of how people experience their lives with the need for formulating a narrative that is more authentically true to the person and better incorporate his/her values and wishes. In other words, what is at stake in recovery from mental illness is a narrative that is more credible (reflects better authentic values of the person) and serves better the keeping of face as part of a kind of impression management [18]. We can further explore what this means for some aspects on the existential continuum and suggest ways that nurses can apply to support service users here. Helping persons with severe mental illness in constructing and developing a meaningful story may be crucial to the transformation of someone’s illness identity.

The Self

When a person falls ill there is the need to find sense and meaning in or beyond suffering. One of the first steps in the recovery process “tends to be the reclamation of a sense of oneself as active agent” , [49], ([41] p.4). Someone progressing towards recovery will feel the need to explain and legitimize his/her fate and keep his/her integrity. With a serious illness someone may wonder “why did I fall ill? Did I do something wrong that elicited this disease?” Finding satisfying ‘good’ explanations for illness or how to cope with it, will restore agency to the person, where this may have been reduced by feelings of guilt for having contributed to the disease by a ‘faulty’ lifestyle or, at the other end of the continuum, feelings of being victimized by blind fate (the disease strikes you from out of the blue) and being stigmatized in a role that identifies you not as the person who you are, but as the archetypical patient with characteristics belonging to the disease. Nurses and other mental health professionals can unintendedly contribute to this selffaulting process by adopting a professional gaze [50] that leaves no room for other interpretations than the medical diagnostic frame [51].

The meaning that people give to their lived experiences and in its wake also their self-image is constantly subject to change, even when this is usually only in a subtle way. Service users will only then be willing to open up to treatment and support if the treatment rationale provides a plausible and credible explanation to them for what they went through and how it affected their functioning and their health. This willingness concurs with the kind of awareness persons develop about their situation and condition. Nurses and other mental health professionals can facilitate this awareness by attending to:

i. What the person is feeling or what he thinks about what is happening to with him at this moment?

ii. How the person explains what is wrong or what has happened with him?

iii. What the person thinks needs to be done?

iv. What examples there are of desirable behavior, may-be only as ‘small miracles’, that already have taken place and can be used for further generalizing to a situation leading to better health and well-being for the patient (De Shazer, cited by Cladder [52]).

Although this open, non-diagnostic reasoning may help service users to make up their own mind, it is nevertheless true that narratives often follow recurring patterns that reflect the interaction between the person and the world around him. There may be a repetition of problems or dilemmas when an existing narrative is used again and again to attribute the same meaning to problems in a range of diverse situations even where another interpretation may be more helpful. A well-known example is the perspective of being a victim that clears the narrator of blame for the upset that he/she is experiencing but also dismisses him/her from a responsibility of actively influencing circumstances. Such a perspective tends to re-affirm itself every time that other people respond in a predictable way, often carried along by a negative spiral of fear, powerlessness, concern and anger. In such a spiral, dynamics of repetition may occur by which the psychiatric disorder or the problematic behavior sometimes tend to become more dominant and the perspective of being a victim is likely to be re-affirmed. It is a function a narrative can have in communication, but not one health professionals consider contributing to health and empowerment. This plotting of a story sometimes seems to follow the lines of a script that cannot be changed. Boeckhorst [53] speaks about ‘demonic spirals’ because they mirror a history of the individual’s failures to find another, more constructive approach to problems in life. Boeckhorst describes how also professionals can be contaminated by this negative communication pattern and how this ‘invites’ the reaffirmation of a certain perspective. Nurses may support service users in their recovery by not going along with these scripts and explore with their clients what other roles they can play in their own narrative.

Time

Every person has a need for a future that he or she can experience as making sense. There is the need for placing oneself in a time perspective in which there is development, which is to experience time as flowing and open to our actions. We have the need to understand ourselves and to be understood by others along the lines of our life story. Nurses can facilitate this by a life review interview: for instance by using the lifeline interview method-LIM [54,55].

The repetition of narrative patterns in how one sees problems and dilemmas in life that we discussed above may cause a change in the existential experience of time [56]. Time can be experienced as flowing slowly and may even come to a halt. Time can be experienced as a stream in which everything recurs. As a consequence a person can lose the notion of being an ‘agent’ (actor), who stands in the world enacting the story of which he himself is the author. Such an existential crisis affects the ‘agency’ of the person and is detrimental to his/her capability to have his/her voice heard and to look into the world with an upturned face. When a person on the other hand has the idea that he is moving forward on the road to a life that answers his/her wishes and is in agreement with his/her deeper felt values (whether spiritual or more down to earth functional and social), then this translates itself in to more vitality and motivation to act accordingly. A person is not always aware of his wishes and values and may be distracted and overwhelmed by the impact of the illness and its consequences for his daily life. The ambitions and hopes he/she once had may have slipped into the background. Then nurses and others may help the person to reminisce and remember (reintegrate) this knowledge again in the conscious mind. Making an inventory of wishes, strengths (anything that a person is good at, feels passionate about or has strong views on) and values may support someone in ‘re-writing’ his/her narrative [57,58].

Recovery is a search and a journey of discovery [59]. What a client will discover cannot be predicted beforehand, let alone whether or not it can be formulated as a goal. What it takes is the will and intention to engage on the journey. Sometimes another, more creative approach is therefore wanted, for instance by inviting service users to make photographs that can serve as starting points for reflection and dialogue about strengths and values [19]. A more creative arts-based approach can better make use of the pre-discursive intuitive knowing. Images can become a more suitable vehicle for a richer reflection than the more abstract and formal asking with linguistic means. Reflection, expression and sharing tend to strengthen each other.

Space/Place

Everyone knows the need for a place where you can be safe and comfortable. When that is assured then there is the need to experience the space where one may stay as a place of action and personal growth and development. The neutral denotation ‘space’ becomes a connotated ‘personal’ place [60] that becomes part of a ‘personal niche’ [42]. People have the need to experience the place where one resides, the wider environment and even the larger landscape in a symbolical sense The sometimes utilitarian (strictly functional) decoration and furnishing of a psychiatric ward do not always enable placeattachment, which can be defined “as an emotional bond established between a person and a place in which a particular place acquires a special meaning for the individual and is associated with feelings of security, control and opportunities for privacy and restoration” [61]. People need a personalized place: “A physical personalised space, such as an apartment or a room, is an important ‘home base’ for securing safety within the personal niche. Personal belongings, but also pets (who often offer valuable company and support), can be part of these physical arrangements.”([42] p.83). Health care professionals can make a difference here by creating a so called ‘healing environment’: warm, welcoming and safe [62]. An excellent example of the efficacy of participatory arts supporting recovery is illustrated by Stickley et al. [63].

The Body

Emotions enable people to embody a story. From their physical appearance (mimicry, muscle tonus and gestures) we can read a story that does not lie (cannot be feigned) and is sometimes more telling than words can convey. Nurses are in the unique position to help someone to express not only the conscious knowledge, but also experiential knowledge, including what lies stored in the body [64]. How people experience things is strongly determined by sensory-motor sensations and skills. Fear is a good example in which the cognitive and the observations and physical sensations are directly related to each other. Vitality is another emotion that people feel in their guts [65]. How to become aware and use this vitality in recovery is what nurses can help people with. Photography for instance has been used as a medium by district nurses and social workers in an ailing city district to help people with chronic health complaints and sometimes social problems to focus on sources of vitality. Making photographs heightened the awareness and an openness that participants had not known for a long time because of their anxiety. The reflection on the photographs and the exchange with other participants contributed to narrative creativity and in this way, there was again space for other perspectives than in the ‘closed’ narratives (circling upon illness and social/financial misery) they held on to until then [66].

People ‘live’ their story, that is: how they interpret what happens to them ‘shows’ in muscle tensions, mimicry and even from the looks in their eyes. The embodiment of experiential knowledge and emotional life can be read by a nurse and put into words where sometimes the service user is not yet able to find the right words. This can be experienced as ‘healing’ and can set the person free, open new horizons and give new energy [64,67,68]. The naming by the nurse of what before could not be named will often be accompanied by a gentle touch or holding of the person. Physical touch can be considered a mode of connection between two spirits [69], which can convey depth of understanding and meaning, including spiritual meanings [70].

The Others

Connectedness is often mentioned by service users as one of the main topics in recovery [71,72]. People feel the need to connect with others and be supported by them.

A space for the ‘other’ is also the interval between the professional and the service user that is not fully filled up with the dominant disease narrative, a ‘place’ for saying of the unsayable and where a new vocabulary can be developed. This means an open encounter between professionals and clients in which reciprocity has been restored, thus contributing to the client’s sense of self-respect. Wilken [42] has expanded the idea of this interval with the notion of interpersonal space. This is connected to the notion of a shared perspective. A shared perspective can only be created when there is reciprocal communication. Real understanding develops when there is a mutual feeling of connectedness and understanding, both on an affective and on a cognitive level. It calls upon a journey to find each other in a constructive way, a process of constructive communication or dialogue.

Professionals can help service users to cope with their emotions and understand them as elements of a personal story. They need empathic resonance to do so, but they can also support the process of making sense of their experiences and recovery by facilitating storymaking, for instance with the Wellness Recovery Action Plan [73], and other peer-led groups. Often, issues of risk dominate mental health care, however Felton and Stickley [74] propose a narrative approach to risk-taking that positions narrative at the heart of risk management.

Summarizing our argument: we started from the assumption that recovery orientated nursing needs to focus on identity, hope, meaningmaking and empowerment and that recovery-oriented care demands emotional intelligence in nurses. We argued that narrative is the vehicle for meaning-making and identity formation and that, in the context of recovery, there is a close link between reconstructing and planning one’s life and the telling of a credible (more authentic) narrative in which one is the agent of one’s own future. We assumed that in order to formulate a goal for achieving a better life one must become aware of important personal values. This is the connection with the existential analysis of who we really are as a person. A number of core aspects or dimensions can be distinguished in this internal representation around which our self-image crystallizes: the self, the body, time, space, the others and the lifeworld. How we experience these nodes in our selfawareness determines our involvement in the world and our interaction with others. The story that goes with it is an ‘enacted’ narrative and is subject to (therapeutic) influences and feedback. We discussed in more detail the social function of narrative and the possibilities for nurses to facilitate service users in the development of their recovery narrative.

Conclusion

We can now sketch the framework of two interacting models of elucidation: a hermeneutic-phenomenological one and a moral one. The first one springs from our understanding that experiences (and how they are reflected on) must find expression and only then can be shared (see the columns in Figure 2). This is the ultimate ground for shared decision making by nurses [75]. Understanding is mediated by enactment and then becomes a lived experience [76]. The second model (the moral model) is related to a set of paired concepts that together represent a moral ontology: place/space and gaze/face and reflections on embodiment and experienced time (the topics in Figure 2). The crucial question may be how the nurse can create and maintain a psychological space, an interval as it were, between him or herself and the service user. The intervening space should not be foreclosed by the dominant medical narrative and the jargon of care professionals. There must be room (space) for the person to tell his/her story and voice his/her perspective. It is not only a psychological space but also how physical spaces can or cannot be experienced as places where there is room for acting instead of just passively receiving and ‘consuming’ treatment. It is necessary that nurses and other care professionals every now and then (or preferably more often) refrain from a diagnostic and clinical look (gaze) and see the patient unprejudiced (face) as a person. The ultimate challenge is to bring together both perspectives (the professional’s and the patient’s) in a dialogue to facilitate a process of shared decision making that truly is grounded in a shared perspective.

References

- Hurwitz B, Greenhalgh T, Skultans V (2004) Narrative research in health and illness. BMJ Books, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

- Balint M (1959) The doctor, the patient and his illness. Pitman, London, United Kingdom.

- Brody H (2003) Stories of Sickness. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- Frank AW (1995) The wounded storyteller. The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

- Gabriel Y (2004) The voice of experience and the voice of the expert: can they speak to each other? In: B Hurwitz, T Greenhalgh, V Skultans (Eds.), Narrative research in health and illness. BMJ Books, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom, pp. 168-185.

- Hamkins S (2014) The art of narrative psychiatry: Stories of strength and meaning. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Holloway I, Freshwater D (2009) Narrative research in nursing. John Wiley & Sons.

- Stickley T, Higgins A, Meade O, Sitvast J , Doyle L, et al. (2016) From the rhetoric to the real: A critical review of how the concepts of recovery and social inclusion may inform mental health nurse advanced level curricula—The eMenthe project. Nurse Educ Today 37: 155-163.

- Pack MJ (2013) An evaluation of critical-reflection on service-users and their families narratives as a teaching resource in a post-graduate allied mental health program: an integrative approach. Social Work. Mental Health 11: 154-166.

- McNamee S, Gergen KJ (1992) Therapy as a social construction. Basic Books, New York, USA.

- Gergen KJ (1994) Realities and Relationships. Soundings in social Construction. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, United Kingdom.

- Nijhof G (2000) Levensverhalen. Over de method van autobiografisch onderzoek in de [life stories. About the method of autobiographic research in sociology]. Boom Uitgeverij: Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Polkinghorne DE (1998) Narrative knowing and the Human Sciences. State University of New York Press, Albany, USA.

- Ricoeur P (1991) From Text to Action. Essays in hermeneutics, II. The Athlone Press, London, United Kingdom.

- MacIntyre A (2001) The Virtues, the Unity of a Human Life, and the Concept of a tradition. In: LP Hinchman, SK Hinchman (Eds.), Memory, Identity, Community. The idea of Narrative in the Human Sciences State University of New York Press, Albany, USA, pp. 241-264.

- Anthony WA (1993) Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990’s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16(4): 11-23.

- Sitvast J (2011) Living with severe mental illness: perception of sickness. J Adv Nurs 67(10): 2170-2179.

- Sitvast J (2015) Recovery in Mental Health Care with the Aid of Photo-stories: An Action Research Based on the Principles of Hermeneutic Photography. Nursing and Health 3(6): 139-146.

- Tan H, Wilson O, Olver I (2009) Ricoeur’s Theory of Interpretation: An Instrument for Data Interpretation in Hermenutic Phenomenology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8(4): 1-15.

- Lindseth A, Norberg A (2004) A Phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci 18: 145-153.

- Maggs Rapport F (2000) Combining methodological approaches in research: ethnography and interpretive phenomenology. J Adv Nurs 31(1): 219-225.

- Grant A, Leigh Phippard BA, Short NP (2015) Re-storying narrative identity: a dialogical study of mental health recovery and survival. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 22(4): 278-286.

- Pilgrim D (2017) Key concepts in mental health. Sage, London, United Kingdom.

- LeFrancois BA, Menzies R, Reaume H (2013) Mad matters: A critical reader in Canadian mad studies. Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc., Toronto, Canada.

- Grant A, Leigh-Phippard H (2014) Troubling the normative mental health recovery project: The silent resistance of a disappearing doctor. In: Zeeman L, Aranda K, Grant A (Eds.), Queering Health: Critical Challenges to Health and Healthcare. PCCS Books, Rosson-Wye, England pp. 100-115.

- Grant A, Biley F, Walker H (2011) Our encounters with madness. PCCs Books

- Tronto J (1993) Moral boundaries. A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Noddings N (1984) Caring, a feminine approach to ethics & moral education. University of California Press, Berkeley, USA.

- Benner P, Wrubel J (1989) The primacy of caring: Stress and coping in health and illness. Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park, CA, United States.

- Todres L, Galvin KT, Dahlberg (2014) Caring for insiderness: Phenomenologically informed insights that can guide practice. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 9: 21421.

- Wojnar DM, Swanson KM (2007) Phenomenology. An Exploration. J Holist Nurs 25(3): 172-180.

- Barker P (2002) The Tidal Model: The healing potential of metaphor within a patient’s narrative. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 40(7): 42-50.

- Barker P (2003) The Philosophical Basis of Effective Care and Treatment in Psychiatry. Paper presented to the Conference, ”Kvalitet, effekt og produktivitet - hvordan kombinere?” - Psykiatriens årlige lederkonferanse, Stavanger, Norway, Europe.

- Grant A (2004) Letter. Mental Health Practice 8(54): 10-11.

- Barker P, Campbell P, Davidson B (1999) From the Ashes of Experience: Reflections on Madness. Survival and Growth. Whurr, London, United Kingdom.

- Basset T, Stickley T (2010) Voices of experience: Narratives of mental health survivors. John Wiley & Sons.

- Romme M, Escher S, Dillon J, Corstens D, Morris M (2009) Living with voices: 50 stories of recovery. PCCS books.

- Quaker Life (2017) Encounters with mental distress, Quaker Books, London, United Kingdom.

- Riessman CK (1990) Strategic uses of narrative in the presentation of self and illness: a research note. Social Science and Medicine 30(11): 1195-1200.

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Lysaker PH (2010) The Impact of Illness identity on Recovery from Severe Mental Illness. American. Journal of Psychiatric. Rehabilitation 13(2): 73-93.

- Wilken JP (2010) Recovering Care. A Contribution to a theory and practice of good care. SWP Publishers, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Bracken P, Thomas P (2005) Postpsychiatry. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

- Cassirer E (1995) The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. Volume 1: Language. Yale University, London, United Kingdom.

- Cassirer E (2008) Taal en Mythe (original title: Sprache und Mythos and Die Begriffsform in mythischen Denken: Gesammelte Werke, Hamburg: Meiner Verlag, 2003. Translated in Dutch by Stephan van Erp & Huub Stegeman. Uitgeverij Boom, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Bruggen van der H (1992) Antropologische verpleegkunde. In: Van der Bruggen H (Ed.), De Delta van de Nederlandse Verpleging. De Tijdstroom, Lochem, Netherlands.

- Goffman E (1974) The Frame Analysis of Talk. In: Goffman E (Ed.), Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, pp. 496-559.

- Foucault M (1973) The Birth of the Clinic. Routledge Classics, London, United Kingdom.

- Sitvast J (2011) Moral learning in psychiatric rehabilitation. Nurs Ethics 18(4): 583-595.

- Cladder H (1999) Oplossingsgerichte Korte Psychotherapie [Solutionfocused brief psychotherapy]. Swets en Zeitlinger, Lisse, Netherlands.

- Boeckhorst F (2003) Duivelse Spiralen. Werkboek voor meervoudig-systemisch denken in de sociale psychiatrie. GGNet, Warnsveld, Netherlands.

- Schroots JJF (2003) Life-course Dynamics A Research Program in Progress from The Netherlands. European Psychologist 8(3): 192-199.

- Schroots JJF, Assink MHJ (2004) LIM | Levensverhaal: een vergelijkende [Life story: a comparative contents analysis]. Tijdschrift voor Ontwikkelingspsychologie 25: 3-40.

- Boeckhorst F (2005) Zeitwelten in der psychiatrischen Arbeit. Familiendynamik 30: 199-216.

- Rapp CA, Goscha RJ (2006) The Strengths Model. Case Management with People with Psychiatric Disabilities. Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York, USA.

- Slade M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Farkas M, Grey B, et al. (2015) Development of the REFOCUS Intervention to increase mental health team support for personal recovery. Br J Psychiatry 207(6): 544-550.

- Higgins A, McBennett P (2007) The petals of recovery in a mental health context. Br J Nurs 16(14): 852-856.

- Sitvast J (2011a) De separeer kan een toevluchtsoord zijn. Tijdschrift voor Ziekenverpleging (TvZ) 1: 43-49.

- Marcheschi E, Laike T, Brunt D, Hansson L, Johansson M (2015) Quality of life and place attachment among people with severe mental illness. Journal of Environmental Psychology 41: 145-154.

- Sitvast J (2016) The Engagement Model, Transition Processes and a New Definition of Health. J Clin Res Bioeth 7(3): 1000275.

- Stickley T, Wright N, Slade M (2018) The art of recovery: outcomes from participatory arts activities for people using mental health services. Journal of Mental Health. J Ment Health 27(4): 367-373.

- Benner P (2000) The roles of embodiment, emotion and lifeworld for rationality and agency in nursing practice. Nursing Philosophy 1: 5-19.

- Damasio AR (1999) The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt Brace, New York, USA.

- Sitvast J (2017) Photography as a Means to Overcome Health Anxiety and Increase Vitality, A Local Group Intervention in an Ailing City District. SF Nurs Heal J 1: 1.

- Wiltshire J (1995) Telling a story, writing a narrative: terminology in health care. Nursing Inquiry 2: 75-82.

- Aranda S, Street A (2001) From individual to group: use of narratives in a participatory research process. J Adv Nurs 33(6): 791-797.

- Chang SO (2001) The conceptual structure of physical touch in caring. J Adv Nurs 33: 820-827.

- Gleeson M, Higgins A (2009) Touch in mental health nursing: An exploratory study of psychiatric nurses’ views and perceptions J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 16(4): 382-389.

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M (2011) Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry 199: 144-152.

- Kartalova O’Doherty Y, Stevenson C, Higgins A (2012) Reconnecting with life: a grounded theory study of mental health recovery in Ireland. J Ment Health 21(2): 136-144.

- Fukui S, Starnino VR, Susana M, Davidson LJ, Cook K, et al. (2011) Effect of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) Participation on Psychiatric Symptoms, Sense of Hope, and Recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J 34: 214-222.

- Felton A, Stickley T (2018) Rethinking risk: a narrative approach. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice 13(1): 54-62.

- Stacey G, Felton A, Morgan A, Stickley T, Willis M, et al. (2016) A critical narrative analysis of shared decision-making in acute inpatient mental health care. J Interprof Care 30(1): 35-41.

- Sitvast J (2014) Hermeneutic Photography: An Innovative Intervention in Psychiatric Rehabilitation Founded on Concepts from Ricoeur. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing 5(1): 17-24.