Perspectives on Emptiness

Darlene Lancer*

Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, Santa Monica, USA

Submission: June 22, 2019; Published: Auguts 06, 2019

*Corresponding author: Darlene Lancer, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, Santa Monica, California, USA. Email: Info@darlenelancer.com

How to cite this article: Darlene Lancer*. Perspectives on Emptiness. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 12(4): 555844. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.12.555844

Abstract

The term emptiness can describe different states depending on our perspective―whether spiritual, philosophical, or psychological. Each person’s encounter is unique. It may be experienced fleetingly or poignantly as a joyful realization of the ultimate reality in the Buddhist sense, or as “existential emptiness,” felt as meaninglessness and alienation when viewing ourselves from a detached, objective perspective. Emptiness is associated with Albert Camus’ “absurd,” Soren Kierkegaard’s “sickness unto death,” Wilfred Bion’s “O,” James Masterson’s “abandonment depression,” Donald Winnicott’s “false self,” and Karen Horney’s “self-alienation.” When facing despair and self-alienation, patients often experience “psychological emptiness,” which is significantly correlated with depression and is deeply rooted in shame. It originates in childhood and can lead to addictive behavior and codependency, “a disease of a lost self.” This presentation draws on writings of philosophers, psychoanalytic theorists, and clinical experience. It explores different states of emptiness and offers ways to approach it individually and clinically.

Keywords: Emptiness; Existentialism; Codependency; Addiction; Depression; Shame.

Introduction

Uplifted, I gazed at the expansive Pacific, gleaming beneath a coral and turquoise dusk sky. Golden ripples ebbed and flowed, while seagulls gathered at the shore. In my peaceful reverie, I recalled the death of my mother decades earlier when this scene had filled me with sadness, emptiness, and isolation. Back then, the vacant ocean mirrored the emptiness that hung over me. The relentless tide and far horizon deepened my despair and sense of meaninglessness. The brilliant sunset and carefree birds only intensified my alienation from life. Passersby shared pleasures and concerns, while I felt robotic, and detached from life.

It’s not unusual to feel emptiness as I did when we mourn the loss of a loved one. However, the term emptiness can describe different experiences depending on the context and our perspective―whether spiritual, philosophical, or psychological, to name a few. Personally, I’ve been unsettled by emptiness arising for no reason when all is well, but also enjoyed its benefits during meditation. This paper will explore these differences and offer some ways to approach emptiness.

Each person’s encounter with emptiness is unique and varies in intensity. It may be indistinct and hard to identify, particularly when uncombine with grief. In fact, unlike sadness, hopelessness, or despair, emptiness is essentially an absence of feelings. We may search for answers, or feel that we, our work, or our life lacks meaning and importance. Why, when, and what we experience depends upon our personality and life circumstances and events. If we highly value relationships, we might feel emptiness when we’re alone. If we primarily value power, we may experience it when our self-esteem isn’t bolstered by aggression, success, or power. If we’re avoiding or repressing our feelings, we may “go through the motions” of living in a disconnected, mechanical manner and experience emptiness as boredom, vague unrest, or restlessness. In this case, emptiness may be a defence to feeling.

Emptiness can be felt fleetingly or poignantly if we’ve been living a shallow or “as if,” inauthentic life—for example, in a narrowly prescribed role, whether culturally or functionally defined, such as a breadwinner or homemaker, or family comedian, rebel, or hero. Without a role to define us, when circumstances change, we may lack the internal resources and connection to our authentic self to sustain us. A life event, such as an “empty nest” or unemployment, can plunge us into the void, revealing the emptiness of our existence.

Emptiness may also be accompanied by disassociation or deadness. Disassociation is the sense of detachment and lack of connection to oneself and external reality. We may experience a floating sensation, nausea, dizziness, psychic numbing, or as if the ground is slipping away. Disassociation can occur during a traumatic event or acute shame experience.

Feelings are often best communicated through metaphor. My experience at the ocean reflected back to me my internal world. A client compared her emptiness to aftermath of a nuclear holocaust― as if she were walking, feeling dead, through a bleak and orange wasteland. Some people experience “hollowness” in the pit of their stomach. A newly divorced man drew a picture of a raft adrift at sea to portray his experience of feeling lost without bearings. Losing a loved one can make not only the present, but also the future, seem unbearably empty. A sense of futility and meaninglessness are always close, stemming from helplessness and lack of energy and desire. Following her initial sorrow after death of her son, my client Martha described the emptiness as not having enough blood in her veins. After losing his beloved Julie, French poet Alphonse de LaMartine [1] laments that he “contemplates the earth as a “wondering shadow,” imagining being carried off in the wind like a “withered leaf.”

In grief we may feel lonely for the loved one we’ve lost, but loneliness is distinct from emptiness. With emptiness, there’s no wanting, nor a sense that something is lacking. We’re unable to care and are devoid of wishes or fantasies. People say they feel nothing and want nothing, or that nothing is worthwhile. LaMartine declares, “I ask nothing of this immense universe;” a mourner’s “indifferent soul knows neither charm nor joy.” In contrast, loneliness is accompanied by sadness, missing, or longing for someone, and a desire to be with others [1].

Existential Emptiness

The experience of emptiness is a universal, existential response to the human condition. It’s our search for personal meaning in the face of a finite existence, as explained by psychoanalyst Erich Fromm [2]:

[Man’s] awareness of himself as a separate entity, the awareness of his own short life span, of the fact that without his will he is born and against his will he dies, that he will die before those whom he loves, or they before him, the awareness of his aloneness and separateness, of his helplessness before the forces of nature and society, all this makes his separate, disunited existence an unbearable prison.

Existential emptiness has been described as “an incompleteness of being,” beyond the reach of love and “more propound than all forms of interpersonal loneliness” [3]. It’s the recognition that we’re all that is, without hope or meaning or anything to cling to. We conclude that there is no ultimate significance or importance to life.

Because existential emptiness doesn’t yearn for anything specific, it doesn’t go away by fulfilling our desires. It can be all-pervasive or suddenly there, but not necessarily in response to an external event. Both loneliness and emptiness are aspects of the same basic anxiety [4], which is often felt as we near the discomfort of these states. It’s the fear of experiencing emptiness that manifests as existential anxiety―an ever present, anxious dread that even lurks beneath happiness, according to the first existentialist Soren Kierkegaard. Existentialism was named by philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. It grew out of the nihilism and alienation fostered in a Godless, meaningless society after World War. Sartre viewed existential emptiness as a consequence of social alienation and spiritual bankruptcy, caused by a lack of meaning and purpose in our relationship to life. He argued that “existence precedes essence” [5], proposing that it’s up to each individual to give life meaning. His views were expressed by many philosophers, writers, filmmakers, and artists, including Martin Heidegger, Rollo May, Paul Tillich, Erich Fromm, Leo Tolstoy, Franz Kafka, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Ernest Hemmingway, T.S. Elliot, and Edward Hopper.

Existentialists maintained that despite seeming to have everything, people were entertained by propaganda, marketing, and the media, but led shallow, discontented lives, alienated from nature, others, and their authentic self [6]. They were avoiding the anguish of facing that their lives were empty, without an afterlife, meaning, or value. Albert Camus vividly portrayed this in The Stranger [7], depicting an absurd universe without hope or illusion, which is described by a man deeply alienated, due to the split between himself and his life the actor and his setting.

Theistic existentialists argued that this emptiness reflected religious poverty that’s not often felt by people “too busy to feel much absence of any kind,” unless they’re shocked into reassessing their lives and sense of meaning by a sudden painful experience [8]. But when it afflicts those who “have it all,” the question arises, what’s the point of existence?

Contemporary philosopher Thomas Nagel [9] points out that we live our lives from a subjective point-of-view, meaning that we place importance on what affects us personally―the most dreaded being the reality of our eventual death, decay, and nonexistence, which we can barely imagine. He states that in contrast, when we take a broader, objective perspective, our daily concerns and the things we value most, even our individual existence, have no significance. Nagel considers that the probability of our conception (and that of our parents and their ancestors), which gave rise to our unique being, was so precarious and fortuitous that its possibility might have perished along with the millions of sperm that didn’t make it on the long journey to fertilize our mother’s waiting egg. Meanwhile, life on earth would have continued without us and will continue after we die. Contemplating this in its extreme deprives human life of all meaning to the point of absurdity, as depicted in The Stanger. We become detached observers, where nothing matters. Our dilemma becomes how to live our lives both engaged and detached without denying either viewpoint.

Spiritual Emptiness

Buddhists as well as Sartre believed that humans are inherently empty―that there is no intrinsic, permanent self. The Buddhist notion of emptiness, called sunyata, originated with Gautama Shakyamuni Buddha in the 6th B.C.E. It has various meanings, including “the void” or undifferentiated, ultimate reality and is both a metaphysical concept and an experiential, meditative mental state. It’s the non-self in Theravada Buddhism. Going further than Sartre, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism consider the contents of consciousness and objects also to be empty and propose that all phenomena lack inherent existence. This doesn’t imply that things don’t exist at all, only that they have no substantial, intrinsic existence, only relative existence.

Hence, it’s quite different from our ordinary understanding of the word. Buddhists turn the concept of “emptiness” on its head. Far from being a painful emotional state, its full realization provides a method to end suffering and reach enlightenment. They don’t get lost in the nihilistic meaninglessness of the existentialists. Per the Heart Sutra, they understand that emptiness and form are inseparable, and that emptiness is also fullness―an overflowing presence [10]. Perhaps the untimely death of Buddha’s mother in his infancy created such a deep void and anxiety that he undertook his quest to understand and relieve humanity from suffering, which he could easily relate to.

You can experience emptiness in meditation by noticing the gap between you as observer and the observed, and between you the thinker and your thoughts. Useful practices are to ask, “Who is thinking?” or to notice the discrepancy between your actions and your plans and intentions [11]. It’s precisely this space, this nothingness, from which freedom arises.

Psychological Emptiness and Depression

Sartre and existential psychologists like Rollo May and Viktor Frankl believed that emptiness was the consequence of modernity. In contrast, Carl Jung thought emptiness was a psychological phenomenon, born of the structural division within the self― the powerlessness of our ego to control our mind [12]. Whereas existential emptiness is concerned with our relationship to life, psychological emptiness reflects a troubled relationship with ourselves. Existential emptiness is considered to be more intellectual and spiritual than psychological emptiness [13,14].

The two types may be difficult to distinguish. However, only psychological emptiness is significantly correlated with depression [14] and is deeply related to shame. Depression includes a variety of symptoms, including sadness and crying, anxiety or restlessness, shame and guilt, apathy, fatigue, change in appetite or sleep habits, poor concentration, suicidal thoughts, and feeling empty.

Psychological emptiness may be felt as restlessness, a void, or a hunger that can drive addictive behavior. Feelings of emptiness, deadness, nothingness, meaninglessness, or isolation can color a constant undertone of depression. Alternatively, these feelings may be felt periodically, either vaguely or profoundly, usually elicited by acute shame or loss, in contrast with existential emptiness, which needs no trigger. In severe cases, meaninglessness can prevail over any sense of responsibility, sending us into the abyss. Significant childhood trauma can leave a “deep inner hell that often is unspeakable and unnamable” [15].

Many other psychoanalysts, including Otto Kernberg, Heinz Kohut, Donald Winnicott, and Wilfred Bion also believed emptiness was a psychological experience. Bion introduced the symbol “O” to represent emptiness or nothingness, which forms the matrix of our sense of self—the divine ground of being, analogous to sunyata that is sought by meditators and avoided by patients [16]. He posited that for an infant, the absence of a mother’s breast creates a space of “no-thing” and “no breast,” a potentially terrifying experience of loss and confusion [17].

Psychoanalyst Karen Horney considered emptiness to be the result of a neurotic process emanating from self-alienation that starts in childhood [18]. Winnicott added that when a mother doesn’t sufficiently adapt to her infant’s needs and gestures, the infant instead adapts to her, thus constructing a false self. Inadequate mirroring can lead to a “depleted self,” which Kohut referred to as an “empty depression” [19]. The resulting disconnection to the real self creates a feeling of emptiness, of “not really living” or “sleepwalking through life” [20].

Deficient maternal attunement and dysfunctional parenting not only lead to psychological emptiness, but also to codependency—“ a disease of the lost self” [21]. Psychological emptiness is common among codependents, which includes addicts and many individuals with mental disorders. Lack of a developed core self is a major issue for codependents. They have difficulty accessing their innate self because their feelings, thinking, and behavior revolve around other people or an addiction. They live externally through the lives of others; whose opinions measure their own worth. This self-alienation derives from lack of awareness and connection to an internal life—their real self. Horney described this as a “paucity of inner experiences, impairing feelings, willing, thinking, wishing, believing” [22].

To the existentialists, a loss of self generates our deepest despair, referred to by Kierkegaard as “sickness unto death,” but it’s a loss that does not clamor or scream [18]. Prolonged self-alienation can be sensed as a vacuum, meaninglessness, nothingness, or apathy. One patient experienced her despair as a “sense of broken reality” caused by the juxtaposition of her hollow, empty persona and the “devouring black hole” of her internal world [15].

The emptiness underlying codependency and addiction is often associated with dysthymia or chronic depression. More severe is abandonment depression, coined by psychiatrist James Masterson, which can result from a childhood devoid of nurturing and empathy and lead to symptoms of depression, emptiness, panic, guilt, rage, and helplessness [23]. The mother may be mentally ill, an addict, and/or codependent herself. Without a soothing and responsive maternal presence, an infant can be terrified by uncomfortable feelings of helplessness, vulnerability, and complete dependency upon adults for survival. Ability to bear panic and frustration depend solely upon knowing that his or her mother will return. This allows an infant to think, reflect, and trust her. Ideally, a baby gradually is able to tolerate a mother’s absence, conjure a mental image of her, and regulate internal states and feelings [24].

Developing this capacity to tolerate separations from our mother affects the way we experience being alone or significant losses as an adult. For many people, including codependents, early deficits are often exacerbated by additional trauma, abuse, and physical or emotional abandonment later in childhood and in adult relationships. The emptiness and grief triggered by my mother’s death was compounded by our lack of closeness, described in a poem I penned at 14, “The Loneliness of Man.” It distills the alienation and loneliness of my early adolescence and laments the human condition of wandering the “distances that abandon our hearts to loneliness,” like “two stars, years apart.”

Because codependents depend on external objects for self-cohesion, they often experience depression and emptiness when they stop their addiction, or when a close relationship, however brief, ends. They may say, “He was part of me;” “She was my reason for living;” “Marijuana made me feel normal;” or “Cigarettes were my best friend.” To the extent the other person or drug served self-object functions, the loss can feel as if part of the self is lost, like the world has died, representing a symbolic death of their mother and of their self.

Emptiness and depression are also the consequence of real deficits when we’re unable to be effective agents in our lives. We miss out on joy, contentment, and an ability to manifest our desires. Without access to the energy of our real self, our belief that we can’t direct our lives is confirmed, increasing our hopelessness and depression. We feel things will never change and that no one cares, while longing to be cared for.

Emptiness and Shame

Emotional abandonment causes not only psychological emptiness and codependency, but also toxic, internalized shame, including associated guilt and low self-esteem, which can follow us throughout life [25]. Parental shaming aside, lack of maternal responsiveness in infancy can contribute to persistent negative affect. When a mother is absent or unresponsive, her baby’s experience of “no-thing” is filled with negative sensory and affective impressions, which if not tolerated, the “no-thingness” can devolve into the disintegrative nothingness of a “black-hole” [24,26]. When a child’s failure to receive empathy and fulfilment of needs is severe or chronic, it profoundly affects his or her sense of self and belonging.

Internalized shame makes us doubt our worth and lovability. It alienates us not only from ourselves, but from others. We then project our own critical self-evaluation onto others, personalize other people’s actions and feelings, and feel guilty and responsible for them, compounding low self-esteem and shame. This perpetuates our childhood erroneous beliefs that if we were different or didn’t make a mistake, our real self would be cherished and accepted by our parent(s).

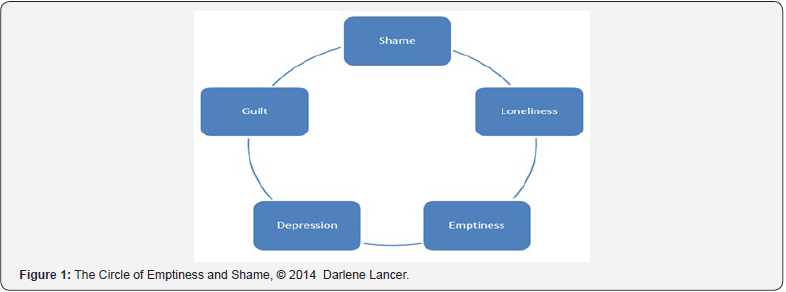

Loss, loneliness, rejection, or the mere awareness of our separateness from others can easily arouse emptiness, shame, guilt, and anxiety. The reverse is also true. Shame and emptiness can create a sense of isolation and rejection and activate feelings of abandonment and shame from childhood. This creates a self-reinforcing, vicious circle, shown in Figure 1. although there is no particular order.

Shame provokes destructive defenses, including defenses to emptiness, which undermine intimate relationships, making it “Love’s Silent Killer”[25]. Low self-esteem and the inability to tolerate emptiness also make it difficult to trust and receive [20]. Moreover, the false self formed to protect us from shame and rejection simultaneously walls us off from the authentic connection we both crave and fear. Shame can result in self-imposed isolation, people-pleasing, and other co-dependent symptoms, which in turn perpetuate self-alienation, shame, depression, and emptiness.

When we’re alone, feel bored, or shift from the stress and pressure of work to non-doing, internalized shame can quickly fill our emptiness with obsession, fantasy, negative thoughts, or self-persecutory judgments. As we struggle with our superego, that is at least something. But when the self is fiercely rejected, our inner conflict is replaced with emptiness.

A client on sick leave following surgery explored her emptiness with me. She also felt guilty imagining that she was burdening and upsetting me if I thought about her between sessions or showed empathy to something sad that she talked about. Tearfully, she said she had to walk a fine line between being interesting enough to gain my attention, but not cause me to react or care too much. She couldn’t believe that I might be interested in her and insisted that my concern was only about her problems, because she wasn’t worthy of my interest in her as a person.

In the codependent mind, internalized shame endures without end. It can convince us that we’re doomed, sentenced by others to a lonely prison that we create. We become both persecutor and victim, tormented precisely because we’re unable to be rid of our loathsome self. “The despairing man cannot die; no more than ‘the dagger can slay thoughts,” writes Kierkegaard [27]. He notes ironically that although Macbeth became king, but shame robbed him of his life, which became empty and meaningless; he lost himself and the capacity to enjoy the fruits of his ambition or the possibility of grace (p. 91). But unlike Macbeth, for codependents, their internalized shame is unwarranted and often unwittingly transferred from their parents.

Emptiness and Addiction

Our inability to bear the self-alienation and shame that accompany psychological emptiness causes inner instability, restlessness, and anxiety. Inadequate love, empathy, and need satisfaction in childhood leaves a traumatic disappointment of ever getting our needs met that is usually unconscious. This hopeless despair creates a hunger and dependency on someone or something to help perform certain internal functions that otherwise would have developed normally. So, we turn to an external source, which may be a leader, another person, violence, or an addiction [11].

We numb our discomfort with distractions and attempt to fill our emptiness through externalization. Addiction, whether to a substance, process, or person, is fundamentally an escape from the real self, independence, and self-expression [23]. This may include dependence on food, exercise, shopping, work, sex, thrill-seeking, or other distraction. Driven by an insatiable need for comfort, validation, attention, and understanding, our behavior can become compulsive. To observers, we may seem greedy, controlling, and indiscriminate. However, because we’re disconnected from our inner source of vitality, our attempts to find fulfilment can lead to self-sacrifice, further discontentment, and depression. This is particularly true of narcissists, who need constant validation to avoid their emptiness. They have an “intense form of object hunger” [28]; also referred to as “intense stimulus hunger” [29].

Emptiness is often associated with eating disorders. But it’s more than an empty gut. One woman explained that her binging filled her emptiness and the “deficiency” in her life [30]. Bulimia and anorexia are thought to be caused in part by spiritual emptiness or “hunger of the soul” in women who lack connection to themselves and others. Their primary relationship is with food, which affords them “an illusion of control and their authentic connection to self, others as well as a higher being, diminish” [31]. In describing her struggle with an eating disorder, Sandy Richardson calls her encompassing emptiness “soul hunger,” which continued on its “vicious, gnawing path” no matter how much she ate [32].

My eating disorder kept me safe. If I was just thin enough, pretty enough, maybe no one would look behind and see what a shameful, bad person I really was. The mask got heavier and heavier until I nearly collapsed under the strain of maintaining the lie. Once in treatment for my eating disorder, I discovered that dieting, food and weight were not the issue. I was trying to fill a void that food could not possibly touch—a soul hunger [32].

Codependents addicted to love, relationships, and romance focus on people to provide motivation, meaning, and companionship. Their relationships frequently involve drama and emotionality, enlivening them to escape their self-alienation. Stable partners seem boring in contrast to addicts, unavailable partners, excitement, conflict, or dysfunctional work environments. Some codependents endure long, abusive relationships, living from one crisis to the next in constant trauma. After many years, they whither into empty shells, devoid of any emotion or sense of themselves. They’re neither alive nor dead but have frozen their feelings to avoid the pain of their marriages.

However, seeking relief from emptiness through distraction, addiction, and externalization provides only a temporary solution and further alienates us from ourselves. When the passion or the addictive high wanes, we become disappointed, and loneliness, emptiness, and depression return. Partnerships formed primarily to reduce loneliness may bring together two lonely people who remain lonely. Forty percent of spouses report feeling lonely sometimes or often [33]. Couples may experience emptiness even when they’re lying in bed next to one another while longing for a passionate, vibrant relationship.

Anxiety and emptiness intensify when we’re alone or stop trying to help, pursue, or change someone else. If we’re rejected or an addictive relationship ends, inner states triggered by loss of the attachment can be so unbearable that some people rather cling to an abusive partner. Letting go and accepting our powerlessness over others can evoke the same desperation and emptiness that addicts experience during withdrawal.

Hence, it’s common to switch addictions. Codependents may replace their preoccupation with a person with compulsive eating, working, drinking, or another compulsive activity. Similarly, when addicts build-up tolerance or stop one addiction, like Edward described below, they often add to it or replace it with another addictive behavior. Nothing satisfies what has become a biochemical need. They may go from drinking to gambling to sex addiction until they address the underlying problems of trauma, shame, and emptiness.

Hemmingway [34] poignantly described how his hunger persisted after he had enjoyed a wonderful meal, and that “the feeling that had been like hunger” continued on the way home, and even after he and his wife made love “. . . it was there. When I woke with the windows open and the moonlight on the roofs of the tall houses, it was there” (p. 48). Nothing could satisfy him. Later, he gave up gambling on the races, and then he understood that his emptiness couldn’t be filled by anything, whether bad or good. “But if it was bad, the emptiness filled up by itself. If it was good you could only fill it by finding something better (p. 52).

Edward, a recovering alcoholic, wanted to leave his emotionally dull marriage to be with his mistress in another city. He periodically struggled with sobriety and was grateful that his new relationship helped him maintain it. During their separations, he described his yearning for her as a restless hunger. He desperately ached to be with her, despite his self-loathing about needing her and any suffering his affair might cause his family. As painful as his longing was, the buried emptiness and shame were worse. He thought he was a wretched failure, yet only felt “himself” with her. Gradually, he realized that his addiction to sex and romance was repeating the same pattern he had of escaping his anguish with alcohol, and that all his attempts to fill his emptiness had only caused more misery and shame. He’d been trying to be rid of his vile self and the dreaded void—but of course, that was impossible.

Facing the Void

Whether we have existential or psychological emptiness, change begins with the realization that emptiness is both inescapable and unfillable from the outside. Schopenhauer [35] referred to it as the “bottomless abyss of its heart,” and that no worldly satisfaction could fill its infinite cravings (p. 573.) People generally regard feelings of emptiness and loneliness as distinct from themselves and cling to the illusion that their inner void could be eradicated, avoided, or filled. They can spend their lives trying to do so, perpetuating endless internal conflict.

Twelve-Step Programs are founded on the premise that cravings and inner emptiness cannot be filled through addictive behaviour, and that relief is spiritual. Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous wrote to psychoanalyst Carl Jung [36], who replied explaining that alcoholism was a spiritual problem―“a spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God,” which he believed to be the answer [36].

The sage Krishnamurti [37] disagrees. He maintains that even God can’t fill our emptiness: “Psychologically, the man who runs away from himself, from his own emptiness, whose escape is his search for God, is on the same level as the drunkard (pp. 55, 109).” According to Krishnamurti, when we identify with the ego as an individual “me,” it creates isolation, but this loneliness is merely consciousness of the self without activity (p. 46). He believed that emptiness and loneliness are inherent in being and cannot be escaped through activity, relationships, knowledge, experience, beauty, love, pleasure, or meditation. Our emptiness and the craving to fill it are the same and can neither be avoided nor redirected. We can thirst for different things, “from drink to ideation,” but craving itself is based on illusion (p. 56). This is because what we seek to escape is within us, part of our own nature.

The nadir of our despair is in fact the turning point. When we abandon all hope and accept our fate, transformation occurs―in us, but not by us―we are the object, not the subject [38]. By abandoning hope and not trying to escape our despair, we derive a humbling powerlessness that enables us to face the void formerly filled by altered moods, mental obsession, and compulsive behavior involved with addiction and codependency. Abstinence and the surrender of control also require courage—courage to face our emptiness and hopelessness. Feelings of anxiety, anger, grief, shame, depression, and emptiness that were previously masked are now revealed. We can feel like nothing [39].

Paradoxically, this “forces a person to get something from himself,” claims family therapist Thomas Fogarty, adding, “the less he tries to get from outside himself, the more he gets . . . From this despair, in a strange way, comes a sense of self-esteem and self-respect” [40]. It initiates a major shift in consciousness back to us and self-responsibility. By embracing rather than avoiding our pain, “We evoke divinity itself. And in doing so, we can hold emptiness, old hurts, fear in our cupped hands and behold our missing hearts” [40].

The Way Home

People eventually discover that they cannot run or hide from themselves or their feelings. However, support is essential to endure our confusion and depression long enough to permit real change, especially where there has been childhood trauma―when the “no-thing” space becomes a horrifying black hole.

Tillich recognized that it takes courage to be oneself and “resist the radical threat of nonbeing” [41]. Beyond escaping and hiding, we must discover and express our real self and pursue self-determined goals. Sartre considered people-pleasing or living a role to meet others’ expectations to be inauthentic and in “bad faith.” To provide meaning to our lives in an otherwise senseless universe, his solution was to assume responsibility, live authentically, and become one’s essential self by “choosing one’s self.” The existentialists encouraged individual decision-making and determination of values that require us to go out on a limb and not be enslaved by social pressure, internal should’s, or fear of abandonment. Similarly, 12-Step programs urge action and personal accountability—living a moral life, taking daily inventory, and making amends.

In writing about food addiction, Geneen Roth [30] suggests a cognitive approach by challenging fear and emptiness with questions like: Where is this emptiness or abyss? Is there a hole inside of you? Would you actually fall into it if you stopped trying, running, or resisting? What might happen? Aren’t you still sitting in your chair? Still breathing, thinking? This creates objectivity, distancing us from our feelings. Meditation can also create space for our feelings, cravings, and our urge to flee. Thai Buddhist teacher Ajahn Cha simply instructs [42]:

Put a chair in the middle of a room.

Sit in the chair.

See who comes to visit.

Westerners find it difficult do nothing, because the “visitors” are usually anxiety, shame, distress, or sleepiness, which, if not genuine fatigue, may itself be a defense mechanism. Nevertheless, be still―even if your mind isn’t, and welcome these visitors. Begin by observing but not identifying with them. Notice how thoughts, feelings, and images change and dissipate by themselves, because they’re merely empty mental constructs. So is the observing “I.”

Krishnamurti [37] taught that because we’re not separate from our emptiness and loneliness, they can only be understood, never escaped or overcome―except temporarily. “I” can observe but cannot act to change them. He advocated loving difficult feelings of loneliness, emptiness, and sorrow by bringing intimate, one-pointed attention―to be in direct communion with suffering without preconceived notions or objections, which turns suffering into love (p. 96). When we remove all barriers to being one with our experience, including thinking about it, the split between observing and experiencing disappears, and fear, loneliness, emptiness, and sorrow dissolve. In this way, emptiness and loneliness can be the doorway to a state of aloneness and contentment. By embracing our pain, we connect with our real self and feel integrated. In place of isolation and emptiness, we experience fullness. Our mind is still, feels no insufficiency, and is no longer seeking; it’s creative and independent, neither resisting, reacting, nor searching for happiness or something outside itself (p. 127).

Calming the mind through deep relaxation or meditation in order to become more present and feel into difficult states, even momentarily, creates a positive shift. Going deeper in order to uncover erroneous beliefs and emotional wounds provides healing. By following internal sensation and trauma that live in the body, we can transmute feelings into something else. This may resurrect memories of prior ordeals and release constricted emotion and energy to allow greater courage, vitality, and creativity to devote to the present.

For Mooji [10] emptiness and joy are synonymous. One patient who was severely ashamed of her appearance fell into a shame spiral [25] of hopelessness and emptiness during a therapy session. We tracked her visceral sensations and accompanying symbolic imagery, which she associated to her place in the family and her mother’s persistent shaming. The imagery evolved into a metaphoric liberation from her role in the family and the constant negative messages she received both from her mother and her own self. Over about 15 minutes, her suffering transformed into perceptions of bliss and inner light. This experience had a lasting effect that changed her self-concept and freed restricted energy. It gave her the courage to return to graduate school and pursue the career she truly wanted.

It’s important to detoxify, understand, and integrate painful emotional states and not drown in them in a manner that reinforces internalized shame. Being alone for months with despair, shame, loneliness, and emptiness that spiral into hopelessness and depression isn’t helpful. It’s often a repetition of childhood trauma when no one provided comfort and nurturance. Psychotherapy provides a method for approaching these states gradually in a secure environment. This is especially important for people with emotional dysregulation or who are newly recovering from long term addiction. A non-judgmental, experienced therapist or spiritual guide can provide a secure holding space and artfully help to examine painful memories, integrate difficult or overwhelming emotions, and challenge and recast faulty beliefs that accompany states of severe shame and emptiness.

Conclusion

Although a variety of ego states and experiences are described as emptiness, only psychological emptiness is linked to depression. It’s predominantly attributable to deficits in early parenting that lead to self-alienation (Horney), abandonment depression (Masterson), a depleted self (Kohut), false self (Winnicott), and codependency. The void not filled by a nurturing parent creates a gap from the authentic self that is later filled with shame, anxiety, depression, and often codependency and addiction as a means to cope with emptiness.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychoanalysis, and other approaches are used to treat depression, shame, and emptiness. One technique to address both transient existential and psychological emptiness is to merge with the experience. Existentialists also emphasize living an authentic life, which is the path supported by Twelve-Step programs. It is recommended that further clinical research be undertaken to compare the efficacy of differing psychotherapeutic, spiritual, and Twelve-Step approaches in ameliorating psychological emptiness.

An earlier, abridged version of this article first appeared in 2014 as “There’s a Hole in My Bucket.” In Lancer, D., Conquering Shame and Codependency: 8 Steps to Freeing the True You, pp.73– 91. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation.

Authors Biography

Darlene Lancer is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and expert author on relationships and codependency. She’s counseled individuals and couples for over 30 years and coaches internationally. Her books include Conquering Shame and Codependency: 8 Steps to Freeing the True You and Codependency for Dummies and seven ebooks, including: 10 Steps to Self-Esteem, How To Speak Your Mind - Become Assertive and Set Limits, Dealing with a Narcissist: 8 Steps to Raise Self-Esteem and Set Boundaries with Difficult People, “I’m Not Perfect - I’m Only Human” - How to Beat Perfectionism, and Freedom from Guilt and Blame - Finding Self-Forgiveness. They’re available on Amazon, other online booksellers and her website, www.whatiscodependency.com, where you can get a free copy of “14 Tips for Letting Go.” She’s a sought after speaker in media and at professional conferences. Find her on on Soundcloud, Clyp.it, Instagram @darlene.lancer, LinkedIn Youtube,Twitter @darlenelancer, and Facebook.

Author Permission

© 2019 Darlene Lancer. Contact Author for permission regarding reuse.

References

- De Lamartine A (2002) “L’Isolement.” (G. Barto, Trans.).

- Fromm E (1958) The Art of Loving. Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, USA.

- Park J (2001) Our Existential Predicament: Loneliness, Depression, Anxiety, & Death. 4th Existential Books, Minneapolis, USA.

- May R (2009) Man’s Search for Himself. Norton, New York, USA.

- Sartre JP (1957) Existentialism and Human Emotions. (B. Frechtman, Trans.). Philosophical Library, New York, USA.

- Bigelow GE (1961) A primer of existentialism. College English 23(3): 171-178.

- Camus A (1989) The Stranger (M Ward, Trans). Vintage International. New York, USA.

- Dupré L (1998) Spiritual Life and the Survival of Christianity: Reflections at the end of the Millennium. Cross Currents 48(3).

- Nagel T (1986) The View from Nowhere. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Moo-Young AP (Mooji) (2017) White Fire: Spiritual Insights and Teachings of Advaita Zen Master Mooji. Non-duality Press, Oakland, California, USA.

- Hazell CG (2003) The Experience of Emptiness.: 1stBooks, Bloomington, Indiana, United states.

- Gunn RJ (2000) Journeys into Emptiness: Dōgen, Merton, Jung, and the Quest for Transformation. Paulist Press, Mahwah, New Jersey, United States.

- Frankl VE (1948) Man’s Search for Meaning. Washington Square Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Hazell CG (1984) A scale for measuring experienced levels of emptiness and existential concern. Psychological Reports 117(2): 177-182.

- Wurmser L (2003) Abyss calls out to abyss: Oedipal shame, invisibility, and broken identity. The Am J Psychoanal 63(4): 299-316.

- Mathers D, Miller ME, Ando O (2013) Self and No-Self: Continuing Dialogue Between Buddhism and Psychotherapy. Routledge, London, UK.

- Reiner A (2012) Bion and Being: Passion and the Creative Mind. Karmac Books, Ltd, London, England, UK.

- Horney K (1950) Neurosis and Human Growth. Norton, New York, USA.

- Kohut H (1977) The Restoration of the Self. Chicago University Press, Chicago, Illinois, US State.

- Winnicott DW (2017) Ego Distortion in Terms of the True and False Self. In: L Caldwell & HT Robinson (Eds.) (1960–1963), The Collected Works of DW Winnicott. Oxford University Press, New York, USA, 6: 159-174.

- Lancer D (2012) Codependency for Dummies (2nd edtn). Wiley, New Jersey, United States.

- Horney K (2000) The paucity of inner life experiences. In: BJ Paris (Ed.), The Unknown Karen Horney: Essays on Gender, Culture, and Psychoanalysis. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA, pp. 283-294.

- Masterson JF (1988) The Search for the Real Self–Unmasking the Personality Disorders of our Age. The Free Press, A Division of MacMillan, Inc, New York, USA.

- Symington N, Symington J (1996) The Clinical Thinking of Wilfred Bion. Routledge, London, UK.

- Lancer D (2014) Conquering Shame and Codependency: 8 Steps to Freeing the True You. Hazelden Foundation, Center City, Minnesota, USA.

- Grotstein JS (1990) Nothingness, meaninglessness, chaos, and the “black hole.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis 26(1): 257-290.

- Kierkegaard S (1955) Fear and Trembling and Sickness unto Death (W. Lowrie, Trans.). Doubleday, Garden City, New York, USA.

- Kohut H (1968) The psychoanalytic treatment of narcissistic personality disorders: Outline of a systemic approach. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 23: 86-113.

- Kernberg O (2004) Aggressivity, Narcissism, and Self-destructiveness in the Psychotherapeutic Relationship. Yale University Press, New Haven USA.

- Roth G (2010) Women Food and God: An Unexpected Path to Almost Everything. Scribner, New York, USA.

- Kleinman S, Nardozzi J (2010) Interview by M. Tartakovsky, Hunger of the Soul in Eating Disorders: Insight from The Renfrew Center. Psych Central.

- Richardson S, Govier SW (2006) Soul Hunger. Remuda Ranch. ACW Press, Ozark, Alabama, United States.

- Tornstam L (1992) Loneliness in marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 9(2): 197-217.

- Hemingway E, Hemingway S (2009) Sean Hemmingway (Ed.). A Moveable Feast: The Restored Edition. Scribner, New York, USA.

- Schopenhauer A (1966) The World as Will And Representation. (E.F.J. Payne, Trans.). Dover Publications (2nd Revised edtn.), Mineola, New York, USA.

- Jung CG (1975) G Adler (Ed.). Selected Letters of C.G. Jung 1909–1961. (R.F. C. Hull, Trans.) Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

- Krishnamurti J (1993) On Love and Loneliness. HarperCollins, San Francisco, California, USA.

- Whitmont E (1969) The Symbolic Quest. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

- Lancer D (2004) Recovery in the 12 steps–how it works. The Therapist 16(6): 68-69.

- Fogarty T (1973-1976) On Emptiness and Closeness. Part I, The Best of The Family. Center for Family Learning 7-9.

- Tillich P (1952) The Courage to Be. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

- McLoed K (2010) A way of freedom, Tricycle.