Positive Thinking Training Intervention: Assessing critical parameters from First Generation Middle Eastern Immigrants Perspectives

Abir K Bekhet1* and Karen Nakhla2

1Associate Professor, Marquette University, United States

2Student, Marquette University, United States

Submission: July 01, 2019; Published: July 25, 2019

*Corresponding author:Abir K Bekhet, Marquette University College of Nursing Clark Hall 530 N. 16th Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States

How to cite this article:Abir K Bekhet, Karen Nakhla. Positive Thinking Training Intervention: Assessing critical parameters from First Generation Middle Eastern Immigrants Perspectives. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 12(4): 555841. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.12.555841

Abstract

Few resources are available to help first generation middle- eastern immigrants (FGMEI) manage their problems and their challenging situations that may impact their physical and psychological well-being. Positive thinking training is an intervention designed to help FGMEI improve their ability to deal with these problems. The purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate the six intervention parameters of an in-person face- to- face positive thinking training intervention (PTTI). Twenty FGMEI participated in this pilot intervention that included (a) participating in a four weeks face to face intervention sessions (one and half hour per session). (b) completing two questionnaires over a 4-week time period (pre-post intervention measures). Data were evaluated within the context of the six parameters essential to the PTTI development namely; necessity, feasibility, acceptability, fidelity, safety, and effectiveness. Results provided initial support for all six parameters with recommendations to improve aspects of the PTTI.

Introduction

Many factors contribute to migration across the globe including, but not limited to, socioeconomic factors and conflict. Although migrant research and its impact on immigrants’ physical health has started to gain more attention in recent years, mental health migrant research remains very limited [1]. The challenges and the stressors that first generation immigrants are facing are undeniable and can compromise their physical and mental health. First generation immigrants reported higher probability for colorectal cancers, diabetes, and heart diseases [2]. Additionally, clinically diagnosed Psychotic disorders is more prevalent in first generation immigrants as twice as those with settled population [3].

Middle eastern immigrants are one of the fastest growing immigrant population in US. The population of middle eastern immigrants is increasing significantly, jumping from less than 200,000 in the 70th to 1.5 million in the 20 centuries [4]. Middle easterners are always classified with the White race and less attention has been given to middle eastern immigrants in general and to first generation middle eastern immigrants (FGMEI) in particular [2]. The challenges that FGMEI facing are enormous, including the language barrier and the acculturation which includes, adjusting to new cultural and legal climates that might be different from their country of origin [3]. In addition, recent immigrants from the Middle East might be unfamiliar with the American laws and the society norms and expectations and this disconnect can lead to conflicts in their daily life and their workplace [5]. Migration also influences social bonds of migrants and can expose them to clinical depression [6]. Research showed that chronic stress and strain are associated with depression [7].

Positive thinking is a cognitive process that creates hopefulness, helps individuals to have better solutions for their problems, and to make sound decisions [8,9]. Positive thinking has been linked with less stress and better health outcomes and has been associated with better work performance, enhanced social relationships, problem solving, coping, and creativity [10,11]. In addition, positive thinking has found to be effective in decreasing high school students’ academic burnout following ten 2-hour positive thinking sessions [12]. Also, positive thinking has been linked with life satisfaction, less depression, finding a purpose and meaning in life, and an overall better quality of life [13,14]. The purpose of this study is to determine the necessity, acceptability, feasibility, fidelity, and beginning effectiveness of a Positive Thinking Training (PTT) intervention from the perspectives of FGMEI designed to help them to deal with their daily stressors.

The PTT Intervention

The PTT intervention is based on cognitive -behavioral theory [8]. The skills of the PTT intervention highlight cognitive activities to increase positive thoughts and to eliminate negative ones. To facilitate learning and reinforcing the skills constituting positive thinking, three mnemonic strategies were used: Acronym, Chunking, and practice. Acronym and chunking to facilitate acquiring the positive thinking skills, and practice for reinforcement [8]. The acronym, THINKING was used to facilitate remembering the eight specific positive thinking skills, which is also a reasonable “chunk” of ideas for participants to remember [15]. For practice, the participants were given a homework in which they were asked to indicate one or two life situations in which they used the PTT strategy. Four face to face PTT intervention sessions were delivered to participants. One session was scheduled every week for four weeks. Each session lasted for oneand one-half hours and included teaching FGMEI the skills that constitute positive thinking.

We started the first session by an introduction to the positive thinking training (PTT) intervention and the acronym THINKING. Then the PTT intervention was delivered to participants as follow:

i. Transform negative thoughts into positive thoughts (week 1);

ii. Highlight positive aspects of the situation (week 1);

iii. Interrupt pessimistic thoughts by relaxation techniques and/or distractions (week 2);

iv. Note the need to practice positive thinking (week 2);

v. Know how to break a problem into smaller part to be manageable (week 3);

vi. Initiate optimistic beliefs with each part of the problem (week 3).

vii. Nurture ways to challenge pessimistic thoughts (week 4) and

viii. Generate positive feelings by controlling negative thoughts (week 4) [8].

During each session, the Positive thinking skills were discussed by the researcher and the participants; examples of life situations where the participants may use each skill were highlighted, discussed, and reinforced by the other participants. Participants were encouraged to identify ways in which each of the skills might be applied within their individual situations. Laminated cards were used as instructional methods along with group discussion and verbal instruction as needed to facilitate learning. Participants were instructed to review the laminated card daily. Reflection on their practice/use of the positive thinking skills served as a mechanism for reinforcing the positive thinking skills.

Methods

Research Design

This pilot intervention study involved pre-post intervention group using methodological triangulation

Sample: The sample included 20 FGMEI participants. Inclusion criteria are as follow: being a first-generation middle eastern immigrant, 18 years and older, and not currently receiving a treatment for depression or diagnosed with depression.

Sample, Setting and Data Collection: Approval for the study was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board. The research assistant contacted the first-generation ME immigrants through religious affiliation in the Milwaukee area. After explaining the purpose of the study and seeking help from the religious community leader, an IRB-approved flyer was posted on the bulletin of the religious affiliation. Those who are interested contacted the researcher to come up with agreeing upon time and place for the intervention. The researcher and the research assistant made sure that the participants are meeting the study criteria and then participants were given the consent form followed by the questionnaires (time 1) that took approximately 20 minutes to answer. The group met in the social hall of the religious affiliation on an agreed upon date and time that is convenient for them after the religious service. The intervention took place once per week for 4 weeks (one and half hour per session). Within a week after the intervention, the participants were given the post intervention questionnaires that took approximately 30 minutes to answer. Participants were given a $20 gift card after time 1 data collection and $25 gift card time 2 post intervention to thank them for their time and participation.

Measures

The Depressive Cognitions Scale (DCS) [16] is an eight-item scale that measures depressive cognitions when scoring is reversed as all the items are phrased positively. The eight-item scale uses a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (5). Possible range of scores is zero to 40, with higher scores indicating more depressive cognition after reverse coding the eight items. The DCS is reliable, as demonstrated by Cronbach’s alpha of .90 in autism caregivers [17]. Construct validity was supported by correlations in the expected directions with CG burden (r = .40; p < .001), resourcefulness (r = −.65; p < .001), sense of coherence (r = −.77; p < .001), and quality of life r = −.70; p < .001 [17]. Factor analysis revealed one factor that explained 48% of the variance [17].

Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS) [18] is an eight-item scale that measures positive thinking as measure of intervention fidelity. All items are scored in the positive direction; higher scores indicate more positive thinking. The total scale scores will range between 0 and 24, with higher scores indicative of more positive thinking. Response options are four-point Likert scales ranging from 0 = never to 3 = always. In a study with autism caregivers, Bekhet & Zauszniewski [8] reported acceptable internal consistency (α =.90) and construct validity, using a measure of positive cognitions (r = .53; p < .01), resourcefulness (r = .63; p < .01), depression (r=−.45; p<.01) and general well-being (r=.40; p <.01) for the Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS). Exploratory factor analysis indicated the presence of a single factor with all item factor loadings exceeding .30; 59% of the total variance was explained.

Measuring and Evaluating the Intervention Parameters

Necessity of the PTT intervention was evaluated by examining baseline scores on the PTT; scores above 13 indicated less need for the intervention [9]. Acceptability of the intervention was assessed by asking the participants to describe what part or parts of the intervention were most, and least, interesting [19,20]. The feasibility of the intervention was evaluated by asking the participants to describe what part or parts of the intervention were easiest, which were most challenging, and whether they thought that the number and length of the sessions were appropriate in terms of time commitment [21].

The fidelity of the intervention was assessed by asking the participants whether they thought they learned all the skills constituting positive thinking and what might have helped to learn them better. Fidelity also was assessed by examining scores on the PTSS since positive thinking scores would be expected to increase if the skills constituting positive thinking were taught effectively [20,21]. The safety of the group intervention was evaluated by asking the participants what part or parts of the intervention were most, and least, distressing or uncomfortable and whether they had any concerns about confidentiality during the group interactions [20]. Effectiveness of the PTT intervention was assessed by asking the participants to describe ways in which the intervention might be improved and by comparing the depressive cognition pre and post intervention and by asking them to describe one or more situations in which they were able to use the positive thinking strategies.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 24 and descriptive statistics were used to examine the sample characteristics. Paired Samples Test were used to examine the pre-post depressive cognition and positive thinking skills scores in FGMEI. Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting the means and dividing the results by the pooled standard deviations and their strength was calculated using Cohen’s recommendations for effect sizes (small = .20, medium = .5, and large =.8, respectively). Content analysis was used to answer the qualitative questions related to the six PTTI intervention parameters namely; necessity, acceptability, feasibility, fidelity, safety and effectiveness.

Results

Necessity of the Positive Thinking Training Intervention

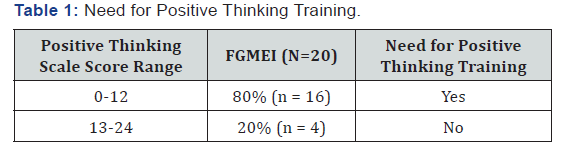

The necessity parameter or whether there is a need for the intervention, was assessed by looking at the baseline scores on the positive thinking skills scale to determine the FGMEI needs for the PTT. Previous research showed that a cut off score of 13 is a point at which referral, intervention, or treatment would be recommended [19]. Consequently, we classified participants based on the cut off score to determine their need for the positive thinking training. Eighty percent of the FGMEI who participated in this study had a need for positive thinking training (Table 1).

Feasibility

Feasibility addresses the time involved in recruitment, enrollment, and retention as well as the cost to deliver the intervention. Participants were asked about the challenges they faced and the convenience of the number and length of the intervention sessions. In this study, recruitment occurred over a 4-week period and twenty subjects were recruited and they all completed time 1 and time 2 questionnaires following the 4 weeks intervention sessions.

One participant did not attend the second session and another one did not attend the third session due to illness in the family and personal circumstances respectively as indicated by the subjects. Challenges FGMEI reported included remembering to apply the techniques learned to everyday life (n=2). One participant stated “How to implement the techniques to everyday life and keep up with it. This was hard,” and “Applying what we learned, need more time to practice”. Participants indicated that the number and length of the sessions were appropriate in terms of time commitment. Nine participants indicated that they would love to have more sessions. Examples included: “Yes, I looked forward to attending each week…. You did a great job. More sessions would be great”; and “Wish it was longer, it was very helpful”

Acceptability of Content and Method of Delivery

Acceptability of the intervention was assessed by asking the participants to describe what part or parts of the intervention were most, and least interesting. Nine participants indicated that the most interesting aspect of the positive thinking intervention was the examples and life stories participants shared with the group. One participant stated, “It was good listening to people experiences especially when they supplement positive experiences with bible verses” Another participant indicated that the most interesting part of the intervention was “Socializations, listen to other strategies and how people deal with life events”. Yet another participant stated, “gain benefits from other experiences and apply them in life”. When participants were asked about the least interesting experience, they indicated “none” and “none it was really helpful, and all the intervention parts were very interesting.”

Safety

The safety parameters assessed whether participants experienced discomfort or distress during the intervention. There were no reports by the participants that they perceived any aspect of the positive thinking training as stressful or uncomfortable and there was no need for medical or psychological referral. All participants completed the 4 weeks intervention program except two participants missed one session because of personal circumstances. Two participants indicated that sometimes they got emotional listening to other participants’ problems. One participant stated “Hearing sad, personal stories. They were not distressing, and they were good to hear but just sad.” Another participant stated, “Listening to people experiences and different situations… I get emotional”. Except for those two participants, other participants did not express discomfort. In the first session, the PI addressed the importance of confidentiality and what will be shared in the room should stayed in the room.

Participants were also asked whether there are any concerns about confidentiality during the group interactions. None of the participants indicated concerns. One participant stated, “confidentiality was addressed well.” Another participant indicated “No. I am a very open person. I may be more concerned though, if I wasn’t so open.” Another participant indicated that it would be helpful to have this discussion before the first session. She stated “No. Not at all. But maybe we should have a discussion about confidentiality before the first session? That’s what I do at work.”

Fidelity

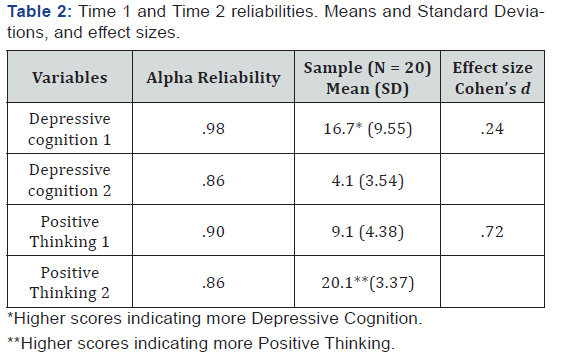

Fidelity refers to a competent delivery of the intervention according to an outlined protocol and involves monitoring to assess whether all steps of a protocol are followed as well as behaviors or measures are improved [20,21]. In this study, delivery of the information was standardized across subjects through the intervention and the group discussion delivered by the PI in all 4 sessions, fidelity was evaluated by examining changes in positive thinking skills scores, which would be expected to increase after the PTT training if the training achieves its intended goals. The PTSS measures the eight specific skills that are taught during the PTT. Scores on the PTT measures from pre- to postintervention for the sample (n=20) showed improvement in positive thinking skills (Table 2). Paired Samples Test showed a statistically significant difference between pre to post intervention scores [t (19) = 8.42, p <.001). There was a medium intervention effect (d =.72) for positive thinking, with an increase in positive thinking scores across time. Ninety five percent (n=19) indicated that they were able to learn all parts of the positive thinking training intervention and one indicated that she learned “most” of the intervention. One participant stated “Yes, we get lucky we had a very good group leader” and “very well presented & learned”.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness parameter evaluated the intervention outcomes. We tested the depressive cognition scale scores pre and post intervention using Paired Samples Test, which showed a statistically significant difference between pre to post intervention scores [t (19) = -5.69, p <.001). There was a small intervention effect (d =.24) for depressive cognition, with a decrease in depressive cognition scores across time (Table 2).

The intervention parameter was also evaluated by asking participants what might have helped them to learn better, 70% (n = 14) stated that nothing more was needed and 30% (n = 6) indicated that they needed more time to practice (n = 2) and more sessions (n = 4). Participants were asked to describe one or more situations in which they were able to use the positive thinking strategies. Following are examples from participants narratives:

“I recently had a serious health concern. The result could be something simple and easy to treat, or it could be more serious – still treatable but more complicated. I tried to stay positive but the stress of not knowing started to make me more anxious. So, I broke the situation down – [telling] myself there are many other causes/reasons for my symptoms; the Dr. doesn’t seem too concerned; and if it is a more serious condition, it is treatable. When reminding myself of these [positives] didn’t calm me, I imagined what would happen if the worst diagnosis happens it would be an early stage, it would be [treatable], I would have a lot of support and my true father and the true physician, Jesus Christ would take care of it. I don’t dwell on the worst, but I know if it happens it will be okay.”

“When I see mess at home, I put fun quotes around that says, (Bless this mess) that makes me laugh & not distressed.”

“It just happened two days ago with my 11 years old son. We have a swimming practice for him, and he was playing on his ps4 and his time was done but as most of kids they don’t pay attention to time and he always wants more time. I calmly asked him and make him aware that it’s time to go, but he didn’t listen so I took an action and turned the internet off so his game was turned off… he got really mad about it [started] yelling and screaming I was really [ frustrated] but I [tried] to think positively and [ tried]one of the [strategies] we talked about in the intervention so I [started] counting in my head from 1 to 10 and I didn’t not respond with anger and I talked with him calmly telling him he should pay attention and use his time wisely.”

“I have three kids with challenging problems. I tried to control my emotions by thinking positively. So, [I told myself] if my son failed this time, he can do better next time. Thinking positively and insert positive thoughts in my mind helped me and helped him to [ succeed] and improve”.

Discussion

This is the first study to test the six intervention parameters of a positive thinking training intervention designed to help FGMEI to cope with the stress of everyday living. The critical intervention parameters of necessity, acceptability, feasibility, safety, fidelity, and potential effectiveness provided a framework for evaluating the face to face positive thinking training intervention. Eighty percent of the FGMEI who participated in this study had a need for positive thinking training as indicated by their baseline scores on the positive thinking skills scale. The content was appropriate, as validated by participants’ narrative about the utility of applying the positive thinking skills through the different situations that they indicated. In terms of feasibility, participants indicated that the number and length of the sessions were appropriate in terms of time commitment. In fact, evaluating those six critical parameters from the intervention recipients’ perspectives, FGMEI in this case, is important as this will likely affect their future use of the positive thinking training and consequently decrease their depressive thoughts and improve their well-being [19].

Limitations of the study included the use of a convenience sample and the lack of control group. The results of the study showed a statistically significant difference between pre to post intervention scores. The effect size estimates suggest medium effects of the intervention on positive thinking and with small effects on depressive cognition. Future experimental research design with a control group, random assignment, and an adequate sample size can test the effectiveness of the positive thinking training intervention within one week after the intervention, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks to measure the immediate and the lagged effects of the intervention on participants’ positive thinking and quality of life.

Fidelity of the face to face PTTI was shown by the increases in scores on the positive thinking skills scale, with high- medium effect size (d= .72). Paired Samples Test showed a statistically significant difference between pre and post intervention scores. Indeed, obtaining a high-medium effect size for the PTTI is encouraging, especially given the small sample size. The findings of this study are similar to the findings of previous study, which showed that the positive thinking skills scores improved following 6 weeks online PTTI among caregivers of persons with autism [21]. In fact, in this study, the face to face positive thinking skills scores improved significantly than the previous online PTTI delivered to autism caregivers. However, it should be noted that the samples and the method of delivery (in-person versus online) are different in both studies. Future research might consider comparing the in-person intervention versus the online intervention in FGMEI and consider giving the participants the choice of the method of delivery.

In general, FGMEI found the face- to- face PTTI to be feasible, acceptable, and they did not report any safety concerns or problems with the intervention. This multimethod pilot study makes an important contribution to the migrant research by demonstrating how assessing six critical parameters are important for future developing and refining the PTTI. This framework provided a structure to the evaluation process, which is essential for improving the health of FGMEI.

Acknowledgement

The study was funded by Marquette University 2017-2018 Explorer Challenge grant awarded to Dr. Abir k. Bekhet.

-

-

- Close C, Anne Kouvonen A, Bosqui T, Patel K, O’Reilly D, et al. (2016) The mental health and wellbeing of first-generation migrants: a systematic-narrative review of reviews. Global Health 12(1): 47.

- Nasseri K, Moulton LH (2011) Patterns of death in the first and Second Generation Immigrants from Selected Middle Eastern Countries in California. J Immigr Minor Health 13(2): 361-370.

- Borque F, Van der Ven E, Malla A (2011) A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first and second generation immigrants. Psychol Med 41(5): 897-910.

- Camarota SA (2002) Immigrants from the Middle East: A Profile of the Foreign-born Population from Pakistan to Morocco. Center for Immigration Studies.

- Firm H (2016) First-Generation Immigrants Face Challenges Adjusting to New York City Employment Laws.

- Lindert J, Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E (2009) Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 69(2): 246-257.

- Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1: 385-401.

- Bekhet A, Zauszniewski J (2013) Measuring Use of Positive Thinking Skills Scale: Psychometric testing of a new scale. West J Nurs Res 35 (8): 1074-1093.

- Bekhet A, Garnier Villarreal M (2017) The Positive Thinking Skills Scale: A Screening Measure for Early Identification of Depressive Thoughts. Appl Nurs Res 38: 5-8.

- Lyubomirsky S, King L (2005) The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness leads to success? Psychol Bull 131: 803-855.

- Naseem Z, Khalid R (2010) Positive thinking and coping with stress and health outcomes: Literature review. Journal of Research & Reflections in Education 4: 42-61.

- Fandokht MF, Sa’dipour I, Ghawam SI (2014) The study of the effectiveness of positive thinking skills on reduction of students’ academic burnout in first grade high school male students. Indian J Sci Res 4(6): 228-236.

- Jung JY, Oh YH, Oh KS, Suh DW, Shin YC, et al. (2007) Positive thinking and life satisfaction amongst Koreans. Yonsei Med J 48: 371-378.

- Lightsey RO, Boyraz G (2011) Do positive thinking and meaning mediate the positive affect-life satisfaction relationship? Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science 43: 203-213.

- Thornton MA, Conway AR (2013) Working memory for social information: Chunking or domain-specific buffer? NeuroImage 70: 233-239.

- Zauszniewski JA (1995) Development and testing of a measure of depressive cognition in older adults. J Nurs Meas 3: 31-41.

- Bekhet A, Johnson N, Zauszniewski JA (2012) Effects on Resilience of Caregivers of persons with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Role of Positive Cognitions. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 18 (6): 337-344.

- Zauszniewski JA, Suresky MJ (2010) Psychometric testing of the Depressive Cognition Scale in women family members of seriously mentally ill adults. Issues Ment Health Nurs 31: 483-490.

- Bekhet A (2017) Online Positive Thinking Training Intervention for Caregivers: Necessity, Acceptability, and Feasibility. Issues Ment Health Nurs 38 (5): 443-448.

- Zauszniewski JA (2012) Intervention development: Assessing critical parameters from the intervention recipient’s perspective. Applied Nursing Research 25: 31-39.

- Bekhet A (2017) Positive Thinking Training Intervention for Caregivers of Persons with Autism: Establishing Fidelity. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 31(3): 306-310.

-