Correlates and Predictors of Externalizing Behavior in Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Kimberly Burkhart*, Nori Minich, Elizabeth Diekroger, Shanna Kralovic and Shanna Kralovic

Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital, Case Western Reserve University, Ohio, USA

Submission: June 08, 2019; Published: July 09, 2019

*Corresponding author: Kimberly Burkhart, Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital, Case Western Reserve University, 10524 Euclid Avenue, Suite 3150, Cleveland, OH 44106,216-983-1209, Ohio, USA

How to cite this article: Kimberly Burkhart*, Nori Minich, Elizabeth Diekroger, Shanna Kralovic and Shanna Kralovic. Correlates and Predictors of Externalizing Behavior in Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 12(3): 555837. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.12.555837

Abstract

Objective: There is not a standardized approach for assessing externalizing behavior in toddlers with ASD. The purpose of this study is to identify correlates and predictors of externalizing behavior in toddlers to inform the assessment process and to gain increased understanding of how quality of life may be impacted.

Method: Participants included 252 caregivers and their toddlers who were evaluated in a multidisciplinary autism evaluation clinic and diagnosed with ASD. 81 toddlers scored in the clinically elevated range on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Externalizing Behavior scale as endorsed by their primary caregiver. Variables of interest included constructs assessed on the CBCL, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS/ADOS-2), and Child and Family Quality of Life Scale (CFQL) – 2.

Results: Toddlers who have a clinically elevated score on the CBCL Externalizing Behavior scale have greater emotional reactivity, anxiety/depression, and sleep problems and poorer overall adaptive behavior and socialization. Those who scored higher on the ADOS/ADOS-2 Tantrum, Aggression, Negative, or Disruptive Behavior item were more likely to have scored in the clinically externalizing range on the CBCL Externalizing Behavior scale. Toddlers scoring in the clinically elevated range on the CBCL Externalizing Behavior scale were rated to have poorer quality of life by their caregiver.

Conclusion: Findings indicate that clinically elevated externalizing behavior problems are relatively common in toddlers with ASD and should be evaluated using a standardized approach.

Introduction

It is estimated that 20% to 70% of youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) exhibit aggressive behaviors [1]. Aggressive behavior is the most prevalent form of externalizing behavior and can impact all aspects of socialization. Campbell and colleagues defined the construct of externalizing behavior “as a grouping of behavioral problems that are manifested in children’s outward behavior and reflect the child negatively acting on the external environment [2].” In a large clinical sample of youth ages 2 to 16.9 years with ASD, 25% of the sample had clinically elevated scores on the Aggression scale on the CBCL. Sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, parent education, race, and ethnicity were unrelated to aggressive behavior problems. Lower cognitive functioning and ASD severity and greater sleep, internalizing, and attention problems were associated with aggressive behavior problems [3].

Farmer and colleagues investigated how aggression in youth with ASD compares to clinic-referred controls [4]. The sample consisted of youth ages 1 to 21 years. Aggression was measured using the Children’s Scale for Hostility and Aggression: Reactive/Proactive subscale and the Aggression subscale on the CBCL. Children with ASD were reported to be less aggressive and to be rated as reactive rather than proactive in comparison to clinic-referred controls. Among all participants, lower scores on cognitive ability, adaptive behavior, and communication were associated with more physical aggression. Younger age was associated with less aggression.

In a parent-rated study of maladaptive behavior in nearly 200 children with ASD ranging from ages 1.5 to 5.8 years, one-third of the sample had a clinically elevated score on total problems on the CBCL. Furthermore, 38.5% were reported to have significant attention problems and 22.5% were clinically elevated on the aggression scale [5]. The prevalence of aggression was examined in 1,380 ASD youth between the ages of 4 and 17 years. Caregivers reported that 68% demonstrated aggression towards a caregiver and 49% towards a non-caregiver with aggression being identified by how the item was endorsed on the ADI-R (no aggression, mild aggressiveness, definite physical aggression, and violence with implements) [1]. The findings of this study suggested that aggression was not associated with clinician assessed ASD symptom severity, intellectual functioning and communication ability, gender of the child, or parent educational level or marital status. Younger children in this sample who came from higher income families, had more parent reported social/communication problems, and who engaged in repetitive behaviors were rated to be more likely to demonstrate aggression [1].

Another database study consisting of 1584 youth with ASD ranging from 2 to 17 years indicated a 53% prevalence rate with the highest prevalence found in younger children. Prevalence of aggression was assessed by asking caregivers to indicate the presence or absence of aggression. In this study, aggression was associated with self-injury, sleep problems, sensory problems, gastrointestinal problems, and problems with communication and social functioning [6]. In addition to there being a paucity of research on standardized assessment of externalizing behavior in toddlers with ASD, there is little research to date investigating the relationship between externalizing behavior and quality of life. ASD youth who display externalizing behavior problems are more likely to receive additional diagnoses, be placed in residential treatment, and to have more intensive medical intervention in adolescence and adulthood [7-9]. This suggests that ASD youth with externalizing behavior may have poorer quality of life.

The purpose of the present study is to identify correlates and predictors of externalizing behavior in toddlers in order to inform the assessment process and make treatment recommendations, as well as to investigate the relationship between externalizing behavior and quality of life for toddlers with ASD (based upon their caregivers’ perception) and their caregivers. While there is some consistency among studies related to predictors of aggressive behavior (e.g. sleep problems and communication/social problems), there is variability in rates of aggression. This is likely attributed to variation in the assessment of aggression and lack of targeting specific age groups within the child and adolescent population. Information needs to be obtained related to predictors of externalizing behavior problems in the toddler population. There is no study to date that focuses on externalizing behavior and assesses the frequency and intensity of externalizing behavior problems in toddlers less than 48 months of age. The most effective and time-efficient way to measure externalizing behavior problems in this population needs to be determined. In addition to this aim, additional information is needed on how quality of life is impacted by the presence of ASD and externalizing behavior in the toddler population.

Maladaptive behavior associated with ASD has been found to cause more distress to caregivers than core features of the disorder [10]. One defining feature of maladaptive behavior is aggression. Aggression is one of the strongest predictors of crisis intervention referrals and familial stress in individuals with developmental disabilities [11,12]. Externalizing behavior is a significant predictor of out of home placements and puts youth at greater risk of being physically abused [13,14]. Parents of toddlers with ASD evidence greater parenting-related stress in comparison to parents of toddlers with other developmental disabilities. Mothers of both preschool-aged children and adult children with ASD report greater negative impact of their child’s disorder and poorer well-being than mothers of children with ASD in other developmental periods [15]. Moreover, behavior problems of preschool-aged children with autism have been associated with greater maternal stress in comparison to adaptive behavior and severity of autism symptoms [16].

There is no study to date that has investigated correlates and predictors of externalizing behavior in children less than 48 months of age who meet criteria for ASD. Also, in need of investigation is whether a single question asking parents to indicate the presence or absence of aggressive behavior is an adequate representation of those who would score in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale as assessed by the CBCL. Obtaining this information would assist with recommendation of a standardized approach to the assessment of externalizing behavior. It was hypothesized that those with externalizing behavior problems would have greater emotional reactivity, anxiety/depression, and sleep problems, and poorer adaptive behavior and socialization.

An exploratory research question was to determine whether externalizing behavioral problems can be detected on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS/ADOS-2) by evaluating observations of disruptive behavior and if symptom severity on the ADOS-2 based on comparison scores is associated with increased externalizing behavioral problems in this age range as endorsed by caregivers. 17 Regression was used to determine which correlates of externalizing behavior explain the greatest variance in externalizing behavior. It was hypothesized that poorer child and caregiver quality of life would be reported for those toddlers scoring in the clinically elevated range on externalizing behavior problems.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of all patients who were diagnosed with ASD in a multidisciplinary developmental-behavioral pediatrics clinic and whose primary caregiver(s) consented to have the child’s assessment results entered into a database. Data collection spanned the years of 2011 to 2018. 427 children between the ages of 13 months and 47 months were assessed in the multidisciplinary autism clinic. Of the 427 children assessed, 252 (59%) were diagnosed with ASD with an average age of 33.28 months (SD = 7.76). Eight-one (32.4%) participants, 67 (82.7%) males and 14 females (17.3%), scored in the clinically elevated range on the CBCL Externalizing Problems scale (T > 63). The average age of these participants was 34.60 months. Fifty-two (65%) patients described their race as being White and 22 (27.5%) reported their race as being Black/African American. The remaining participants were either Asian or indicated their race as being Other/Mixed. There was no significant difference between those who scored in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale and those who did not based on race/ethnicity and gender. Children with Medicaid were more likely to be rated in the clinically elevated range on externalizing behavior, χ2 = 10.76 (1, N = 249, p = .001). Forty-nine (61.3%) participants with elevated externalizing scores had Medicaid coverage versus 66 (39.1%) participants with scores less than 64.

The patients who scored in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale had a total language score within the very low range/severe range on the Preschool Language Scales (PLS), Fifth Edition (M = 64.13; SD = 14.14) and in the low range on the Adaptive Composite on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS), Second Edition (M = 67.58; SD = 9.87). Positive relationships have been found between intellectual ability and communication and serves as a representation of cognitive ability and overall adaptive behavior in the present sample [17,18].

Procedure

Parents of children <48 months of age referred to a multidisciplinary autism evaluation clinic at a Midwestern children’s hospital completed a medical questionnaire and the Modified-Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) [19]. If the child failed the M-CHAT, the division staff then completed the M-CHAT follow-up interview (M-CHAT FUI) via phone call with the parent [19]. A developmental-behavioral pediatrician (DBP) who is the director of the clinic reviewed the paperwork to identify those children at high risk for ASD (e.g., positive family history or referral from a medical provider) to evaluate in the multidisciplinary clinic.

Children qualified for the multidisciplinary clinic evaluation if they met one of the following criteria: Child failed the M-CHAT follow-up interview, a physician contacted the director to specifically request an evaluation for ASD, or the intake questionnaire indicated that the child is demonstrating significant core symptoms of ASD and/or had a family history of a pervasive developmental disorder.

The multidisciplinary assessment clinic evaluation included 2 visits with assessments by DBPs, pediatric psychologists, and speech-language pathologists. Assessment tools included the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Preschool Language Scale – Fourth Edition and Fifth Edition, and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale – Second Edition (VABS). Additional questionnaires used to inform diagnostic impressions included the CBCL, Conners’ Forms Short Version (if appropriate based on age and symptom presentation), and the Child Developmental Inventory [1,20-25]. The diagnosis of ASD was determined at a team meeting after completion of the evaluations and by consensus of the clinical team consistent with DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria [26,27]. At the third parent visit, the pediatric psychologist reviewed the findings of the evaluation and how they contribute to the diagnoses and discussed the medical, educational, therapeutic interventions, and parent resource recommendations. This information was provided to the parents verbally and as a written report.

Measures

Adaptive Behavior

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (Vineland-II) Survey Form asks caregivers to identify whether their child usually, sometimes or partially, or never performs various behaviors within the domains of Communication, Daily Living Skills, Socialization Skills, and Motor Skills. The domains are combined to form an Adaptive Behavior Composite score, which has a standard score of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Test-retest reliability has been established with reliability coefficients values exceeding 0.85 [23].

Language

The Preschool Language Scales, Fifth Edition (PLS-5) is an interactive assessment of developmental language skills. This evaluation assesses total language, expressive communication, and auditory comprehension. It is administered to children ages birth to 7:11. Composite scores have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Split-half reliability (ranging from .80 to .97), sensitivity (.83), and specificity (.80) is high [22].

Global Assessment of Internalizing Symptoms and Externalizing Behaviors

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is completed by caregivers of children ages 1.5 to 5 years. The CBCL consists of items asking caregivers to rate the frequency of each behavior on a three-point scale with options of not true, somewhat or sometimes true, and very true or often true. The Attention Problems (9 items) and Aggressive Behavior (25 items) scales combine to form the Externalizing Problems scale. Both the syndrome scales and composite scores are reported in T-scores with an average of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Adequate reliability and validity for scale scores have been reported [7].

Autism Spectrum Disorder

The Autism Spectrum Disorder Observation Schedule (ADOS/ADOS-2) is a semi-structured, standardized assessment of communication, social interaction, play/imaginative use of materials, and restricted and repetitive behaviors. Adequate reliability estimates for internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, and test-retest reliability have been found.17 The Tantrums, Aggression, Negative or Disruptive Behavior item was also evaluated. This item asks for the clinician to indicate any form of anger or disruption beyond communication of mild frustration or whining on a scale of 0 (not disruptive, destructive, negative, or aggressive) to 3 (shows marked or repeated temper tantrums or significant aggression). Comparison scores, which are based on severity scores derived from percentiles of raw totals corresponding to each ADOS diagnostic classification will be used [28]. The Toddler Module and Modules 1, 2, and 3 were administered.

Quality of Life

The Child and Family Quality of Life Scale – Second Edition (CFQL-2) asks caregivers of children with ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders about their psychosocial quality of life (QoL) [29]. The CFQL-2 was developed based on the CFQL. The CFQL-2 included one question deletion from each CFQL subscale, as well as one addition to each subscale to be able to monitor change in response to treatment intervention. The specific domains of psychosocial QoL measured on this scale includes child, family, caregiver, financial, social support, partner relationship, and coping QoL. The CFQL has shown strong psychometric properties including good reliability across the score range, excellent construct validity, and good convergent and discriminant validity with other clinical measures [30]. For the present sample, internal consistency for the child quality of life scale and caregiver quality of life was .62 and .68, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Windows, Version 24.0. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to describe the sample and variables of interest. Chi-square analyses were conducted to determine whether there was a significant relationship between elevated behavior problems and other variables of interest. Independent samples t-tests and Mann Whitney U-tests were used to examine differences between toddlers with ASD and clinically elevated externalizing behavior scores and toddlers with ASD who do not have clinically elevated externalizing behavior scores on continuous measures (emotional reactivity, anxiety/depression, sleep problems, socialization, overall adaptive behavior, and child and parent quality of life). Logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between clinically elevated behavior problems and the disruptive behavior item on the ADOS/ADOS-2. A stepwise regression model was developed to determine what optimally predicts externalizing behavior in toddlers with ASD.

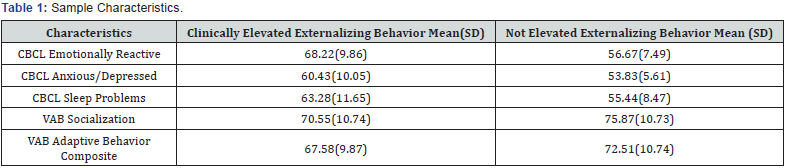

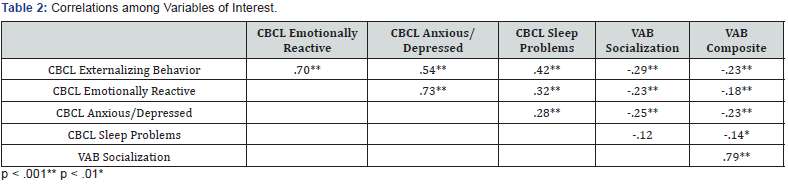

Results

The variables of interest for the present study were as follows: CBCL Externalizing Problems scale, CBCL Emotional Reaction scale, CBCL Anxiety/Depression scale, CBCL Sleep Problems scale, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite, Vineland Socialization scale, and the ADOS comparison score and Tantrum, Aggression, Negative or Disruptive Behavior item. Please see Table 1 for sample means and standard deviations and Table 2 for correlations among key study variables.

Primary caregivers’ were asked on the demographics questionnaire to indicate whether their child is aggressive (yes or no). There was a significant difference between the expected and observed frequencies X2(1, N = 240) = 50.92, p < .001. Seventy-nine children scored in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale with 68.4% of parents endorsing yes on the demographics questionnaire and scoring in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale.

As predicted, those with clinically externalizing behavior problems had higher scores on the CBCL scales of emotional reactivity [Mdn = 67; U = 2,322.50, p < .001], anxiety/depression [Mdn = 59; U = 3,899.50, p < .001], and sleep problems [Mdn = 62; U = 3,511.50, p < .001]. Based on completion of the VAB scales, as predicted, children with clinically elevated externalizing behavior problems had poorer overall adaptive behavior [t(232) = -3.38, p < .001] and socialization [t(233) = -3.56, p < .001] than those who did not score in the clinically elevated range.

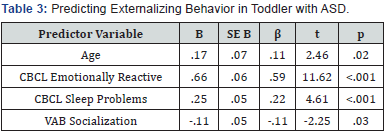

An exploratory research question was to assess whether externalizing behavior problems would be detected on the ADOS-2 and if those with clinically elevated externalizing behavioral problems have greater autism symptom severity as assessed by the comparison score on the ADOS-2. Nearly 60% of the sample had a comparison score as a result of being administered the ADOS-2. There was not a significant difference on the comparison score based upon whether the child scored in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale. Children who scored a 3 (shows marked or repeated temper tantrums or significant aggression) on the Tantrum, Aggression, Negative or Disruptive Behavior item were more likely to have scored in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale than children who scored a 0 (not disruptive, destructive, negative, or aggressive); OR= 4.44; 95% CI = 1.49 to 13.29, p = .008. Of the key study variables of interest that were significantly correlated with externalizing behavior, a stepwise regression was completed to determine what optimally predicts externalizing behavior. Predictors for externalizing behavior included child age, emotional reaction, sleep problems, and socialization. This model was significant, F(4, 229) = 65.31, p < .001 accounting for 52.5% of the variance in externalizing behavior Table 3. It was predicted that child and parent quality of life would be poorer for those with clinically externalizing behavioral problems. Child quality of life was rated to be poorer [t(81) = -4.37, p < .001], but there was not a significant difference for caregiver quality of life.

Discussion

Although externalizing behavior problems are often comorbid with ASD, there is not a standardized method for assessing externalizing behavior. If evaluation involves assessment of aggression or externalizing behavior, typically only a single question is asked. Further investigation was needed to determine whether this practice is sufficient. In the present sample, 32% of the sample was rated to be in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Problems scale. This is a somewhat lower percentage in comparison to other studies, which is likely because a dimensional approach (i.e. CBCL) was taken rather than asking a single question to indicate the presence or absence of aggression. Approximately 68% of caregivers responded yes to their child exhibiting aggression on the demographics questionnaire and endorsed items consistent with scoring in the clinically elevated range on the Externalizing Behavior scale. Although agreement is significant and a single question did relatively well at identifying elevated externalizing behavior problems in this study, these findings indicate that a single question does not capture all children with behavioral problems suggesting that one question may be insufficient. This also suggests that when assessing for outward behavior that negatively affects the environment including questions that assess for attention is needed.

An interesting and unexpected finding is that there was a significantly higher percentage of children who had Medicaid coverage and who were rated to be in the clinically elevated range on externalizing behavior problems. It could be that adverse childhood experiences (e.g. living in poverty) that correlate with government-funded insurance and externalizing behavioral problems in neurotypical toddlers also applies to toddlers with ASD. It is recommended that further investigation be conducted on how adverse childhood experiences may impact toddlers with ASD.

The findings of this study suggest that toddlers with ASD and clinically elevated externalizing behavior problems are perceived to be more emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, have greater sleep problems, and have poorer socialization skills and overall adaptive behavior. This is consistent with Kanne & Mazurek’s findings, as well as Mazurek and colleagues’ findings, which assessed for aggression across the full age range of youth with ASD [1,6]. Based on the results of this study, when clinically elevated externalizing behavior problems are identified, internalizing symptoms, sleep problems, and socialization should be further assessed, and treatment recommendations provided. It is possible that improvement in any one of these areas could decrease externalizing behavior problems. Behavioral strategies to improve sleep and a possible referral to sleep medicine should be considered. Referral to receive Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) should be provided as ABA has been associated with improving adaptive behavioral functioning [31].

Consistent with findings in older children with ASD, disruptive behavior is not typically observed on the ADOS/ ADOS-2 despite caregivers endorsing that externalizing behavior is displayed in other settings [1]. This is the first study to explore whether externalizing behavior is associated with higher severity scores. The findings from this study indicate that higher externalizing behavior is not associated with higher severity of autism spectrum disorder. This might suggest that externalizing behavior can improve independently of autism symptomatology.

There is no study to date that has investigated caregivers’ perception of their toddler’s QoL comparing those with clinically externalizing behavior and those who do not. Based on the results of this study, caregivers perceive toddlers who have ASD and elevated externalizing behavior problems as having poorer QoL than other toddlers with ASD without clinically elevated externalizing behavior. However, caregivers of this study are not reporting poorer QoL. This is an interesting and unexpected finding.

There are limitations to the present study. Correlates and predictors of externalizing behavior was based only on caregiver report. Future studies should include additional informants, such as daycare providers and preschool teachers. Another limitation is that the study is comprised of toddlers with low verbal skills suggesting that the results may not apply to toddlers with language skills in the average range. In addition to including additional informants, future studies should explore if those with Medicaid coverage are more likely to be rated as displaying clinically elevated externalizing behavior problems in comparison to those covered by commercial insurance or whether this finding was unique to this sample. There are several strengths of the current study including being the first to the authors’ knowledge to explore the prevalence, correlates, and predictors of clinically elevated externalizing behavior in toddlers with ASD. This study has provided a better understanding of problems that may underlie externalizing behavior that need to be addressed. This study highlights the importance of assessing externalizing behavior using a dimensional approach.

References

- Kanne SM, Mazurek MO (2011) Aggression in children and adolescents with ASD: Prevalence and risk factors. J Autism Dev Disord 41: 926-937.

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M (2000) Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Dev Psychopathol 12: 467-488.

- Hill AP, Zuckerman KE, Hagen AD (2014) Aggressive behavior problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and correlates in a large clinical sample. Res Autism Spectr Disord 8(9): 1121-1133.

- Farmer C, Butter E, Mazurek MO, Cowen C, Lainhart J, et al. (2015) Aggression in children with autism spectrum disorders and a clinic-referred comparison group. Autism 19(3): 281-291.

- Hartley SL, Sikora DM, McCoy R (2008) Prevalence and risk factors of maladaptive behavior in young children with autistic disorder. J Intellect Disabil Res 52(10): 819-829.

- Mazurek MO, Kanne SM, Wodla EL (2013) Physical aggression in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 455-465.

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2000) Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, Burlington, Vermont, US.

- Mandell DS (2008) Psychiatric hospitalization among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 38(6): 1059-1065.

- Tureck K, Matson JL, Turygin N, Macmillan K (2013) Rates of psychotropic medication use in children with ASD compared to presence and severity of problem behaviors. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 7(11): 1377-1382.

- Brereton AV, Tange BJ, Einfeld SL (2006) Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability. J Autism Dev Disord 36: 863-875.

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic KA, Edelbrock C (2002) Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and without developmental delays. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 107(6): 433-444.

- Shoham Vardi I, Davidson PW, Cain NN (1996) Factors predicting re-referral following crisis intervention for community-based persons with developmental disabilities and behavioral and psychiatric disorders. Am J Ment Retard 101(2): 109-177.

- McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Baker BL (2002) Behavior/mental health problems in young adults with intellectual disability: The impact on families. J Intellect Disabil Res 46(3): 239-245.

- Sandra M Stith, Ting Liu L, Christopher Davies, Esther L Boykin, Meagan C Alder, et al. (2009) Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior 14(1): 13-29.

- Smith LE, Seltzer MM, Tager-Flusberg H, Greenberg JS, Carter AS (2008) A comparative analysis of well-being and coping among mothers of toddlers and mothers of adolescents with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord 38: 896-889.

- Hastings RP, Koushoff H, Ward NJ, Brown T, Remington B, et al. (2005) Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of preschool children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 35: 635-644.

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC (2002) Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2). Manual: Modules 1-4. Western Psychological Services: Torrence, California, USA.

- Klin A, Saulnier C, Sparrow S, Cicchetti D, Volkmar F, et al. (2007) Social and communication abilities and disabilities in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: The Vineland and ADOS. J Autism Dev Disord 37: 748-759.

- Robins DL, Fein D, Barton ML, Green JA (2001) The modified checklist for autism in toddlers: An initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 31(2): 131-144.

- Rutter M, Le Coutear A, Lord C (2003) ADI-R: Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised WPS Edition. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles, USA.

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couter A (1994) Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord, 24(5): 659-685.

- Zimmerman IL, Steiner VG, Pond RE (2002) Preschool Language Scale (4th Edn). The psychological Corporation, San Antonio, Texas, Australia.

- Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balka DA (2005) Vineland adaptive behavior scales (2nd Edn). American Guidance Service, Circle Press, USA.

- Conners CK, Pitkanen J, Rzepa SR (2008) Conners (3rd Edn) Conners. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B (eds). Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. Springer, New York, USA.

- Ireton HR (1992) Child Development Inventory. Behavior Sciences Systems, Minneapolis, USA.

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, Virginia, USA.

- Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C (2009) Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 39(5): 693-705.

- Frazier T (2010) Time course and predictors of health-related quality of life improvement and medication satisfaction in children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treated with the methylphenidate transdermal system. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 20(5): 355-364.

- Markowitz LA, Reyes C, Embacher RA, Speer LL, Roizen N, et al. (2015) Development and psychometric evaluation of a psychosocial quality-of-life questionnaire for individuals with autism and related developmental disorders. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice.

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, Roane HS (2011) Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis. Guilford Press; New York, USA.