Early Onset Anorexia Nervosa – Case Series

Jiri Koutek, Jana Kocourkova and Iva Dudova*

Department of Child Psychiatry, Charles University Second Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Motol, Prague, Czech Republic, Europe

Submission: April 24, 2019; Published: May 03, 2019

*Corresponding author: Iva Dudova, Department of Child Psychiatry, Charles University Second Faculty of Medicine, University Hospital Motol, V Uvalu 84, 15006 Prague, Czech Republic, Europe

How to cite this article:Jiri Koutek, Jana Kocourkova, Iva Dudova. Early Onset Anorexia Nervosa – Case Series. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2019; 11(4): 555818. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.11.555818

Abstract

Early onset anorexia nervosa in prepubertal age is a clinical challenge requiring a specific approach that respects developmental circumstances, clinical characteristics of patients and specific methods of their treatment. Authors are presenting the series of cases (16 patients -13 girls and 3 boys) with early onset of the disease up to 12 years and 6 months of age, admitted to a department of child psychiatry with anorexia nervosa at an average age of 11 years and 10 months. Diagnostic approach corresponds to findings from other authors. Interesting findings include, in particular, the occurrence of self-harm (44%) and suicidal ideations (62%).

Keywords: Eating Disorders, Early Onset Anorexia Nervosa, Diagnostics, Therapy, Abdominal Pain, Child Depression Index, Epilepsy, Psychiatric Hospitalization, Psychopharmacotherapy, Weight loss, Suicidal Behavior.

Introduction

Food intake disorders occur mainly in girls and young women with the development of symptoms often in childhood and adolescence. The highest incidence being between the 13th and 15th year of age. However, we are increasingly confronted with the occurrence of eating disorders, especially anorexia nervosa, in younger patients, with so-called early onset anorexia nervosa [1]. Bravender et al. [2] point to an increased incidence at approximately 10 years of age. The term “early onset” of anorexia nervosa was used for patients between 8-14 years of age, sometimes premenstrual patients were included in the early onset of the disorder. As in adulthood, there are more girls than boys suffering from anorexia nervosa. In adulthood, this ratio is quoted at 1:10; but in childhood, the proportion of boys in the cohort increases [3,4]. The diagnostic criteria for eating disorders listed in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition [5] also apply to children and adolescents, but developmental aspects in the cognitive, emotional and social fields, including family relationships, must also be taken into account. The area of biological development that leads to a number of changes, including the need to accept adolescence, is also important. In childhood, simplified clinical criteria are recommended to diagnose anorexia nervosa: deliberate weight loss (e.g. avoidance of food, induced vomiting, excessive physical exercise, abuse of laxatives), inappropriate perception and beliefs about weight or figure, obsessive attention to weight and body. The sequence of pubertal events (for example the onset of periods) is delayed or even arrested [5].

Other characteristics of anorexia nervosa in children include personality features of avoidance, emotional withdrawal and social conformity, while perfectionist features are also common. There is a tendency to deny intentional starvation, children often complain of anorexia and abdominal pain. The comorbidity with depression and obsessive compulsive disorder is frequent. Triggering factors may include change of school or group of peers, problems in family relationships, and experience of loss. In childhood, the role of the family is important, family relationships are applied both in the development of the symptomatology and in its maintenance. Conflicts with parents concerning food are practically always present. At the same time, these are often children who have so far complied with the parents in all aspects. If the relationships in the family have not been disturbed before the onset of the disease, they will be affected by its development. The therapy must be adapted to the developmental period – it is necessary to take into account the differences in developmental tasks of pre-pubertal, pubertal and adolescent children, the character of their personality and the family relationships [6,7].

Methods

The target group was girls and boys admitted to inpatient care at the Department of Child Psychiatry of the Motol University Hospital in Prague with anorexia nervosa during 2016. Patients were younger than 12 years and 6 months. Other including criterion for girls was primary amenorea. There were a group of 16 patients, of which 13 were girls and 3 were boys, on average 11 years and 10 months of age at the beginning of their admission to the hospital. The patients were especially examined with a semistructured psychiatric and psychological interview that focused on the symptoms of anorexia nervosa, comorbid psychopathology, the presence of suicidal behavior and self-harm, and the family situation. The examination included the CASPI suicide risk questionnaire and the CDI scale. The Child-Adolescent Suicidal Potential Index (CASPI) contains 30 items that focus on depressive symptoms, suicidal motivation and family issues [8]. The CDI (Child depression index) scale is a self-assessment method for assessing depression in childhood and adolescence, containing 27 items [9].

Results

Gender and Age of the Patients

The group comprises 16 children, 13 girls and 3 boys. The proportion of boys in this group is 19%. The average age of admission to the hospital is 11 years and 10 months with the average age of onset of 11 years and 4 months. On average, 7 months have passed between the first symptoms and the admission. The age of the youngest patient regarding the onset of symptoms was 9 years and 10 months and 10 years and 2 months regarding admission.

Family History

Parents got divorced in the child’s family in six cases, in five cases one of the parents suffered from a psychiatric disorder, in two cases it was food intake disorder, in two cases depression and in one case schizoaffective disorder.

Clinical Picture, Diagnosis, Comorbidity

In the examined case series, significant fear of putting on weight, body dysmorphic disorder, and reduced food intake were found in all children. Excessive physical exercise was also present in 10 children. According to ICD-10, the diagnosis was anorexia nervosa in 15 cases and in one case it was atypical anorexia nervosa, because the weight loss diagnostic criterion was not met. Some comorbid psychiatric disorders were present, once it was obsessive-compulsive disorder, moderate depressive phase and acute response to stress, twice it was comorbid anxietydepressive disorder. Epilepsy was present in one case. In the evaluation of premorbid personality development, increased features of introversion were found in seven cases, perfectionist features in nine cases and increased ambitions also in nine cases. In two cases the development of the personality was assessed as significantly more unbalanced.

Self-Harm and Suicidal Ideations

Self-harm was present in seven cases, in 10 cases suicidal ideations were identified by clinical examination. The examination included CASPI suicide risk questionnaire and CDI scale. Cut-off score 11 and higher was found by CASPI questionnaire in six cases. In CDI Scale, cut-off score 14 or more was present in seven cases. In five cases, positivity was present in both tools.

Pre-Inpatient Care

Outpatient psychiatric care was administered in seven cases, out of which three were supplemented by psychological care. In three cases, the children were only in psychological care. Three patients were transferred to a department of child psychiatry from a pediatric inpatient clinic where general pediatric examination was recommended with the subsequent diagnosis of a food intake disorder. Somatic cause of their weight loss was eliminated. Two children were sent for psychiatric hospitalization by their pediatrician. In one case, the child was admitted to the department of child psychiatry urgently after the parents had brought it to the emergency, without previous outpatient care.

Therapy

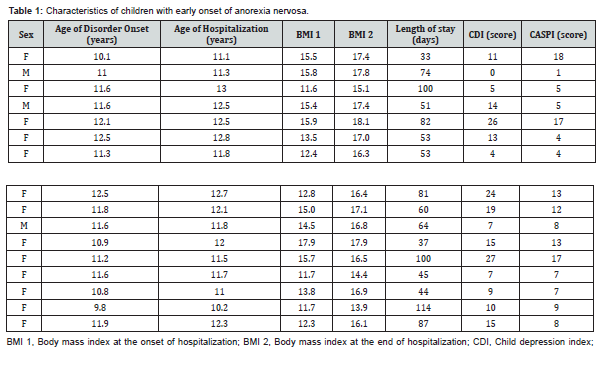

All patients underwent a range of treatments focused, on the one hand, on the improvement of their biological condition and the state of nutrition, on the other hand, on their mental state, including attitudes towards eating and their own body. They were all included in the psychotherapy that consisted of individual and group psychotherapy, art therapy and music therapy. In all cases, family therapy were performed. Psychopharmacotherapy was also used in the treatment, relatively often, in 12 cases medication with SSRI antidepressants, in three cases in combination with anxiolytics. As a result of comprehensive care, all children, except for the girl with atypical anorexia nervosa, gained weight, averaging 2.64 BMI units (Table 1). For all children, psychiatric outpatient care and psychotherapeutic care have been recommended after their dismission, in addition to the usual observation by their pediatrician.

CASPI, Child-Adolescent Suicidal Potential Index.

Discussion

Anorexia nervosa is a disorder associated especially with adolescence and young adulthood, which corresponds to the usual diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches [10,11]. However, there are an increasing number of cases occurring in younger age groups [12]. In younger children as well as in adolescents and adults, there are more girls than boys, but the number of boys is higher than the usual ratio of 1:10. In our group, it was 19% of boys. The types of the symptoms depends on the developmental stage, both on biological, psychological and social levels [13,14]. Our group included girls with primary amenorrhea. In ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa [5] is included amenorrhea or primary amenorrhea. On the other hand, DSM-5 [15] does not contain the diagnostic criterion related to amenorrhea anymore. Nevertheless, an examination by a child gynecologist may be advised to evaluate the patient’s hormonal situation, suggesting possible treatment [12]. All patients suffered from body-image distortion with fear of gaining weight. Weight loss was mostly due to a diet or excessive exercise, often a combination of both. Abuse of appetite suppressants and/or laxatives was not detected in the group, probably due to lower age. However, at such a low age, the personality features of perfectionism and increased ambition that we encounter in older patients are often already present [16].

On average, seven months have lasted since the first recognized symptoms until admission to the department od child psychiatry. Previously, children were in pediatric or pedopsychiatric outpatient care. In our group, early therapeutic intervention and early onset of treatment was a significant positive predictor of success in treatment. In 44% of cases, self-harm and in 62% of cases, suicidal ideation was detected. These clinical symptoms are therefore more common than the suicidal risk identified in the CASPI questionnaire. Suicidal ideations were associated with experience of depression, which was confirmed by CDI in seven patients. There was obviously a link to symptoms of anorexia nervosa, in the sense of fear of gaining weight due to being forced to eat. Suicidal behavior accompanying eating disorders is often reported in other authors [17,18].

Self-harm does not have the purpose of dying, but it is a significant risk factor for suicidal behavior in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa [19]. Our patients have reported self-harm as a motive to reduce stress from fear of gaining weight and/or selfpunishment for having eaten something. Self-harm was therefore closely related to the issue of food intake disorder and it is known that it often occurs with anorexia nervosa [20].

The developmental stage should also be considered in a complex therapy. Chidren are treated with a variety of behavioral therapy, psychotherapy and family therapy. Pharmacotherapy may be used in indicated cases [17]. In our group, SSRI antidepressants were used in 12 cases, both due to the presence of depressive symptoms, as well as for reducing anxiety and fear of eating and gaining weight. In psychotherapy, it is necessary to reflect that cognitive and mental abilities are not at the same level as in adolescents. Younger children are unable to work with introspection than adolescents or adults and their inner problems are manifested as impaired behavior and/or somatization. It is also appropriate to use non-verbal and play techniques in the psychotherapeutic process. Behavioral and somatic therapy is mainly focused on normalizing eating habits, improving biological status and weight gain. It is necessary to emphasize that without improving the child’s somatic state, psychotherapy alone cannot improve the child’s condition. When determining the ideal physiological body weight, it is important to reflect the fact that the diagnostic criterion of BMI 17.5 or less quoted in the ICD-10 refers to eighteen-year-old and older patients. An anthropometric examination is required to determine the ideal physiological body weight for the future. This examination requires to take into account individual biological maturity with respect to age, height and skeleton structure.

In family therapy, it is necessary to respect the child’s dependence on parents, the need to work with parents to increase their parental competence. In our case series, one of the complicating factors was the lack of insight of the disease. Compliance was therefore problematic, both with the child and often with the parents who are under stress of the child who refuses to be treated. On the one hand, it is important to work with possible triggering factors in the family, on the other hand it is inappropriate to strengthen the guilty feelings of parents for the child’s difficulties. The family situation can contribute to the onset and maintenance of symptoms, but the disorder itself also complicates family relationships.

Conclusion

Anorexia nervosa, as well as other eating disorders begin most often in childhood and adolescence. Some of these disorders begin in early prepubertal age. Authors in the presenting series of cases describe 16 patients with early-onset of anorexia nervosa and their specific characteristics. In this case series, it is unique the high percentage of self-harm, suicidal intent and SSRI use. Good clinical practice includes the cooperation of pediatricians with child psychiatrist, psychologist and other involved experts.

Acknowledgement

This paper was supported by Ministry of Health, Czech Republic - conceptual development of research organization, Motol Univesity Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 00064203 and by the Charles University programme Progres Q15 “Life course, lifestyle and quality of life from the perspective of individual adaptation and the relationship of the actors and institutions.”

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Nicholls DE, Lynn R, Viner RM (2011) Childhood eating disorders: British national surveillance study. The Br J Psychiatry 198(4): 295-301.

- Bravender T, Bryant-Waugh R, Herzog D, Katzman D, Kriepe RD, et al. (2010) Classification of Eating Disturbance in Children and Adolescents: Proposed Changes for DSM-V. Eur Eat Disorder Rev 18: 79-89.

- DeSocio JE, O‘Toole JK, Nemirow SJ Lukach ME, Magee MG (2007) Screening of Childhood Eating Disorders in Primary Care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 9: 16-20.

- Bayes A, Madden S (2011) Early onset eating disorders in male adolescents: a series of 10 inpatients. Australasian Psychiatry 19(6): 526-530.

- World Health Organisation, International Classification of Diseases (1992) (10th edn) WHO. Geneva, Europe.

- Herpertz Dahlmann B, van Elburg A, Castro Fornieles J, Schmidt U (2015) ESCAP Expert Paper: New developments in the diagnosis and treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa – a European perspective. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 24: 1153-1167.

- Rome SE, Ammerman S, Rosen DS, Keller RJ, Lock J, et al. (2003) Children and Adolescents With Eating Disorders: The State of the Art. Pediatrics. 111(1): 98-108.

- Pfeffer CR, Jiang H, Kakuma, T. (2000) Child –Adolescent Suicidal Potential Index (CASPI): a screen for risk for early onset suicidal behavior. Psychol Assess. 12: 304-318.

- Kovacz M (1992) The Children´s Depression Inventory. Multi-Health Systems: North Tonawanda, United States.

- Rosen DS (2010) Clinical Report – Identification and Management of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 126(6): 1240-1253.

- Espie J, Eisler I (2015) Focus on anorexia nervosa: modern psychological treatment and guidelines for the adolescent patient. Adolesc Health Med Ther 6: 9-16.

- Rosen DS (2003) Eating disorders in children and young adolescents: etiology, classification, clinical features, and treatment. Adolescent Medicine. 14(1): 49-59.

- Raevuori A, Keski-Rankonen A, Hoek HW (2014) A review of eating disorders in males. Curr Opin Psychiatry 27(6): 426-430.

- Peebles R, Wilson JL, Lock JD (2006) How do children with eating disorder differ from adolescents with eating disorders at initial evaluation? J Adolesc Health 39: 800-805.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th edn) American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, Virginia, USA.

- Lock J, La Via MC (2015) Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. 54(5): 412-425.

- Mcintosh VW, Jordan J, Carter AF, Luty SE, McKenzie JM, et al. (2005) Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 162: 741-747.

- Bulik CM, Thornton L, Pinheiro AP et al. (2008) Suicide attempts in anorexia nervosa. Psychosom Med 70(3): 378-383.

- Koutek J, Kocourková J, Dudová I (2016) Suicidal behavior and self-harm in girls with eating disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 12: 787-793.

- Fennig S, Hadas A (2010) Suicidal behavior and depression in adolescents with eating disorders. Nord J Psychiatry 64(1): 32-39.