Walking the Tightrope: Perceived High Workload, Positive Affectivity and Counter Productive Work Behaviors in the Nigerian Context

Fabian O Ugwu* and Festus O Asogwa

Department of Psychology, Federal University, Nigeria

Submission: January 19, 2018; Published: February 05, 2018

*Corresponding author: Fabian O Ugwu, Department of Psychology, Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo, Ebonyi State, Nigeria, Tel: (+234)80- 65010205, Email: fabian.ugwu@funai.edu.ng

How to cite this article: Fabian O Ugwu, Festus O Asogwa. Walking the Tightrope: Perceived High Workload, Positive Affectivity and Counter Productive Work Behaviors in the Nigerian Context. Psychol Behav Sci Int J. 2018; 8(3): 555739. DOI: 10.19080/PBSIJ.2018.08.555739

Abstract

In environments of underperforming economy, employees are usually under pressure to raise their game so that their organisation becomes more competitive. In doing so, the employees tend to pay a price in the form of increased workload. It is argued in the present study, that employees' experience of high workload might in fact backfire and may lead to increased counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). It is also argued that the availability of positive affectivity (PA) may intervene to reduce the propensity of such employees engaging in CWBs. Data were gathered from a sample of employees (N = 206) drawn from commercial banks in Southeastern, Nigeria. The data were analyzed using moderated hierarchical regression statistics. As expected, the results of the study revealed that perception of high workload was directly and positively related to CWBs. Also, consistent with speculation, PA was significantly and negatively related to CWBs. Specifically, the result showed that high PA attenuated the positive relationship between perceived high workload and CWBs. Findings indicated that employees with high PA engage less in CWBs despite having perception of high workload. These findings suggest that employees should be encouraged to maintain positive emotions while dealing with work-related issues in their organisation so as not to think of retaliation through engaging in CWBs.

Keywords:Bank workers; Counterproductive work behaviors; Perceived workload; Positive affectivity

Abbreviations: OCB: Organisational Citizenship Behaviours; PA: Positive Affectivity; CWB: Counterproductive Work Behaviours; NA: Negative Affectivity; AET: Affective Event Theory; JD-R: Job Demands-Resources; OND: Ordinary National Diploma; TLX: Task Load Index; MD: Mental Demand; PD: Physical Demand; TD: Temporal Demand; FR: Frustration; EF: Effort; PE: Performance; PANAS: Positive And Negative Affect Schedule

Introduction

Just shortly after Davis-Blake and Pfeffer announced that dispositional effects were an illusion; Ashford and Humphrey emphasised that 'research has generally neglected the impact of everyday emotions on organisational life' [1,2]. Interestingly, one year later, House, Shane, and Herold reported that the empirical research base convincingly exposes the ability of dispositional variables to predict organisational-relevant outcomes [3]. Then few years later, Shaw, Duffy, Abdulla, and Singh affirmed that 'dispositions as critical variables in organisational life have garnered considerable attention in the past few years' [4]. All these are clear indication that dispositional variables have followed remarkable trajectory in the research agenda. Although, Shaw et al. [4] claim that the trend of dispositional research has moved away from identifying dispositional components of job attitudes, and toward identifying how dispositions interact with job attitudes and situational factors in the workplace, Shaw et al. cited Weitz who suggested that a clearer picture of job attitudes and behaviours would be evident if individual's disposition was taken into account.

Ever since, individual disposition as an organisationalrelevant construct has continued to attract research attention. For example, Spector and Fox found strong positive relationship between positive affectivity (PA) and organisational citizenship behaviours (OCBs) and between negative affectivity (NA) and counterproductive work behaviours (CWBs) [5]. This result emanated from the fact that individuals high on PA reflect the degree to which an individual feels energetic, enthusiastic, cheerful, active, and alive; they have social potency and volatility [6,7]. Also, PA individuals have a more positive outlook of the world and so engage more in OCB instead of CWBs [8]. On the contrary, employees who are high on NA tend to be less satisfied with themselves and their environments, interpret stressful conditions as disturbing and threatening, are often lethargic [9]. They perceive imbalances and may view negative outcomes as enduring [10,11]. This attribution leads employees high on NA to indulge in CWBs instead of OCBs. Furthermore, Fox, Spector, and Miles found a weak moderating effect of affectivity job stressor-CWBs relationships. Penney and Spector and Salami found support for the role of negative affectivity as a moderator between job stressors and CWBs [12-14]. Dalal in his meta- analytic study found that PA has a negative relationship with CWBs and NA has a positive relationship with CWBs. In that same direction, the current study aims to explore whether PA could be related to CWBs among Nigerian employees and to demonstrate its moderating role in the relationship between workload and CWBs [15].

However, related studies have been conducted in America, Europe, and Asia but none has been studied in Nigeria save who examined job stress, negative affectivity and CWB among 422 secondary school teachers [16-18]. No study to our knowledge has yet investigated the moderating role of PA in the relationship between perceived high workload and CWBs. This view is supported by Raman et al. [18] who asserted that results on dispositional variables (e.g., affectivity) are inconclusive and called for more studies particularly from non-western samples. The present study is a response to a call for more studies to broaden our knowledge of PA, an individual disposition, which researchers have termed an often under studied dimension of affectivity examines both the direct and interactive effects of PA on CWBs [4]. Cropanzano, James, and Konovsky suggested that it is important for researchers to focus on PA to enhance our understanding of the moderating role of affective disposition in workplace situations [19]. In fulfilling these aims, a task of adding to existing knowledge about dispositions and negative work behaviors is accomplished.

Research context - Nigeria

The Nigerian banking sector has undergone tremendous administrative reforms in the past few years. This recapitalisation was engendered by bank deregulations policy to usher in new competition that will reposition the sector and to save it from collapse. This has resulted to a rapid change in how Nigerian banks do business. All this was targeted at increasing the capital base of banks. In the process many of the banks were either acquired or merged, while some others which couldn't meet up with the stringent measures were closed down. This led to downsizing of the workforce with attendant increase in job insecurity. Other outcomes of the administrative changes are more demands from customers and regulators with regard to the availability and quality of worker service delivery. This new demands have imposed excessive workload on the few workers not affected by the shake-up. Meanwhile, the Nigerian banking sector is reputed for its long hour culture and high workloads of employees which may trigger encumbered employees to engagement in negative work behaviors such as CWBs.

Literature review

Workload represents a job demand [20]. It is always found to be a major predictor of burnout [21]. Workload is one of the most frequently reported job stressors in organisations that is often associated with various forms of CWBs [22]. Workload can be considered in terms of number of hours worked, level of production, or even the mental demands of the work being performed. A high workload creates doubts in employees about whether they can accomplish all the work expected of them [23]. Indeed, Krischer, Penney, and Hunter showed that workload would more likely lead workers to act CWBs toward organisation or its members [24]. PA refers to the tendency to experience intense pleasant feelings, social activity, and attitudes involving reward signals [25,26]. It reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, and alert [19,7]. On the other hand, NA is related to health problems, daily hassles, arguments, and unpleasant feelings [27]. NA describes individuals who have high trait levels of subjective distress and nervousness and a tendency to experience unpleasant emotional states [28].

CWBs are actions that can result from wide range of underlying causes and motivations that harm the organisation or its members [29,30]. They comprise a range of acts that are either directed toward organisations (CWB-O) or toward other colleagues in the same organization (CWB-P). Examples of CWB- Os include destroying organisational property, deliberately doing work incorrectly, and taking unlawful work breaks, whereas hitting a coworker, insulting others, and shouting at someone are forms of CWB-P. Although these concepts tend to be conceptually different, recently, all these incidents are now considered within an omnibus term that includes broad class of constructs regarding harmful behaviors at work, that also include aggression, deviance, retaliation, and revenge [31]. CWBs are widespread among employees in many organisations as indicated in public scandals during the 21st century [32]. According to Raman et al. [18], much of it apparently goes unnoticed or unreported. Bennett and Robinson reported that 15% of employees in their study had at one time or the other stolen from their employer [33].

Cohen [29] estimated that 33% to 75% of all employees have engaged in behaviors such as theft, fraud, vandalism, sabotage, and voluntary absenteeism. It has been demonstrated that CWBs have both individual and organisational implications. For example, in the Northwestern Life Insurance Company up to 7% of employees sampled reported being victims of physical harassment [29,34]. Being the target of these broad CWBs can lead to an employee's decreased job satisfaction and increased stress and intentions to quit, among other things [35]. For the organisation, Bamfield reported that more than one-third of all retail shrinkage was attributed to employee theft as revealed in a study conducted in 32 countries across North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific [36]. Chappell and Martino reported that bullying (a form of CWBs) costs Australian employers between 6 to 13 billion Australian dollars each year [37]. Harris and Ogbonna put the estimation of the loss in the US at $200 billion annually [38]. CWBs lead to huge financial losses and may also threaten her reputation. CWBs are considered the most costly behaviors when measured in terms of damage they bring upon organizations. Researchers have reported the cost of various incidents of CWBs, especially in developed countries of America and Europe. Although Nigeria may not have accurate record of incidences of CWBs, observations show that these behaviors are pervasive in Nigerian work organizations.

Theoretical background

The Affective Event Theory (AET) proposed by Weiss and Cropanzano could be key in explaining the relationship between perceived high workload and CWBs [39]. This theory states that affective reactions to work activities are related to diverse types of work-related outcomes. When an event is experienced (e.g., high workload), the employee first appraises the situation in terms of its relevance and importance and thinks about associated consequences [40]. These appraisals are influenced by the dispositional traits of the employee and finally result in the experience of discrete emotions such as anger or happiness [39]. This theory suggests that when a stressful event occurs (perceived high workload) our behavioral outcomes rely on the cognitive and emotional evaluations of the event. Lazarus explains that positive and negative emotions experienced are dependent on whether the situation at hand improves or threatens well-being and these emotions subsequently motivate an individual to engage in a particular behavior [41,42]. Lazarus explains that resultant behaviors are elicited with the intention to reduce negative state affect and enhance positive state affect [43].

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model could explain the direct and interactive effect of perceived workload on CWBs [44,45]. JD-R model assumes that every profession has its own peculiarities in terms of risk factors associated with job-related stress. These factors can be classified into job demands and job resources, thus constituting a robust model that may be applied to various occupational settings. The JD-R model attempts to incorporate two fairly independent research traditions: the stress research tradition and the motivation research tradition. According to the model, job demands produce health impairment process and job resources bring about motivational process. The model specifies how demands and resources interact to predict key organizational outcomes.

Development of hypotheses

Perceived workload and CWBs: High workload has been identified as one of the most important causes of burnout [46]. A high workload is likely to make workers feel uncertain about whether they can get all of the work done [23]. Increase in workload is positively related to declining job satisfaction, reduced ability to meet learners' needs, significant incidences of psychological disorders leading to increased absence from work and a high proportion of claims for disability [47,48]. Jonge and Peters [49] found that the incidence of deviant workplace behaviour among workers was due to excessive workload that the workers have to accomplish. Other studies also found that role overload as a job stressor was positively related to deviant behaviours [8,50]. Krischer et al. [24] showed that workload would more likely lead to an act of CWBs toward organisation rather than toward organisational members. Based on the above argument, it is speculated that:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived high workload of bank employees will be significantly and positively related to CWBs.

Positive affectivity as a moderator: The activation of positive emotion appears to undo or counteract the physiological responses activated by distress reactions [51,52]. Isen asserted that an activation of positive emotions makes people better and more creative at solving problems, and may also improve their handling of interpersonal conflicts [53]. Fortunato and Harsh found PA to be positively related to perceived sleep quality [54]. PA, which is a component of the affective domain of subjective well-being, is also one of the indicators of happiness (subjective well-being) and psychological adjustment [55]. When the negative relation between stress and subjective well-being is being evaluated, it is pertinent to think that PA can reduce the effect of perceived workload on CWB [56]. It has also been shown that individuals who are better at coping with stress may handle stressful situations by activating or maintaining positive emotions [57]. Prabha and Sandeep found that PA significantly moderated the relationship between occupational stress and ill-health of the supervisory level employees [58]. Colquitt et al. [59] found a corrected correlation of -.14 between positive state affect and CWBs. This implies that a positive disposition would attenuate the manifestation of the effects of workload, since high PA individuals generally view situations in a positive light. Because PA is associated with positive feelings, it is likely therefore that it will be negatively related to CWBs. It therefore makes an empirical sense to hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 2: PA will be significantly and negatively related to CWBs.

Hypothesis 3: PA will significantly moderate the positive relationship between perceived high workload and CWBs, such that the relationship will be weaker when PA is high than when it is low.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A total of 206 volunteer bank employees sampled from 11 commercial banks in south-eastern Nigeria took part in the study. The participants consisted of 55 percent males. Their ages ranged from 28 to 54 years, with a mean age of (M= 36.47 years; SD = 3.96). These participants have average organisational tenure of 8.72 years and average job tenure of 7.47 years. The lowest and highest academic qualifications of the participants were Ordinary National Diploma (OND) and Master Degrees respectively. Participants that are married constitute 49.3 percent. Ninety-nine (43.6%) of these employees were on contract appointment. However, a total of 227 set of scales were distributed to the participants in the 11 banks sampled. Out of this number, 13 (5.7%) copies were lost bringing the numbers that were completed and collected to 214 copies, representing 94.3% response rate. Out of the 214 copies returned, 8 were discarded due to improper completion and 206 copies were considered for data analyses.

Instruments

Perceived workload: Perceived workload was measured using the NASA Task Load Index (TLX) [60]. The NASA-TLX is one of the most famous instruments to assess overall subjective workload. It is a multidimensional instrument that consists of 6 subscales: Mental Demand (MD), Physical Demand (PD) and Temporal Demand (TD), Frustration (FR), Effort (EF), and Performance (PE). Twenty-step bipolar scales are used to obtain ratings on these dimensions. Responses ranged from very low to very high. These six sub-scales are combined to create an overall workload scale. Sample items include: 'How much mental activity is required to perform your job?' (Mental demand), 'How much physical activity is required to perform your job?' (Physical demand). Cronbach's a coefficient of 0.85 was established for the present study.

Positive Affectivity: PA was measured using the PA markers from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). The PANAS has 20 descriptors 10 for PA (e.g., enthusiastic, excited, proud) and 10 for NA (e.g., irritable, alert, ashamed) and each respondent indicated the extent to which they experienced each PA descriptor in general. Responses were recorded on five-point scales ranging from (1) Not at all to (5) All the time. Cronbach'sa of 0.89 of the scale was established for the present study.

Counterproductive Work Behaviours (CWBs): Bennett and Robinson's 19-item CWB measure was chosen to represent the construct of CWBs [33]. Participants responded on a 1 (never) to 5 (every day) scale, indicating how often they engage in behaviours, such as 'made fun of someone at work.' The scale has 7 items that represent interpersonal (CWB-P) and 12 that represent organisation directed (CWB-O). The internal consistency for CWB-I and CWB-0 was 0.82 and 0.81 respectively. The present study took a composite approach of the scale and taken together; the total scale reliability for this study was 0.90.

Control variables

Several control variables were included in the model to keep away potential confounds and to reduce the possibility that variables not measured could account for aspects of the results. Eight variables served as control: age, gender, marital status, employment status, job position, organisational tenure, job tenure, and education. They were included as control because earlier studies found them to be related to CWBs, satisfaction and other attitudes [61].

Strategy for analyses

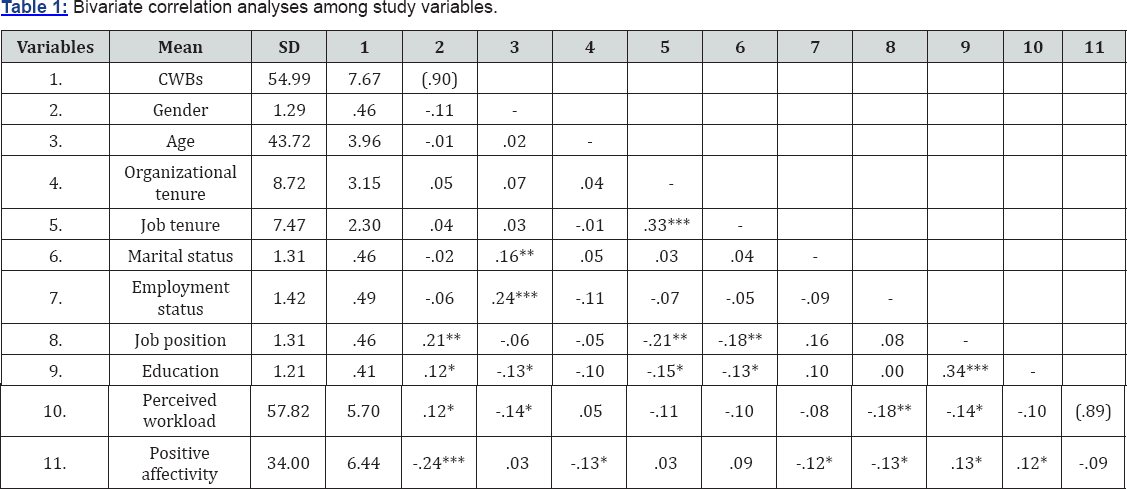

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to test the hypotheses, according to the procedure outlined by Cohen and Cohen [62]. The significance of the interaction effect was assessed after controlling for all main effects. The eight control variables were entered first, followed by perceived workload in the second block; PA was entered in the third block whereas the interaction was entered in the fourth step. Changes in R2 for the model and standardised regression coefficients for each variable in each model were examined. In addition, the researcher reported the unique change in R2 for each predictor variable [62]. This procedure, at times referred to as the usefulness approach, offers an assessment of the distinctive contribution of each predictor in the final equation [63]. As shown in Table 1 above, the results of the correlation analyses revealed that among all the control variables tested, only job position (r = .21, p <.01) and education (r = .12, p <.05) were significantly related to CWBs. Perceived workload was significantly and positively related to CWBs (r = .12, p < .05) whereas positive affectivity was significantly and negatively related to CWBs (r = -.24, p <.001).

Note: *** = p< .001; ** = p< .01; * = p< 05. N = 206. Cronbach's a for applicable scales are reported in parenthesis along the diagonal. Gender was coded 1 = male, 2 =female; Employment status (1- full time, 2 = contract), marital status (1 = married, 2 = single), job position (1 = senior, 2 = junior), Education (1 = high, 2 = low). Organisational tenure, job tenure and age were coded in years (that is, they were entered as they were collected). Perceived high workload and PA were coded, such that higher scores indicated high perception of workload and high PA.

Note: *** = p< .001; ** = p< .01; * = p< .05.

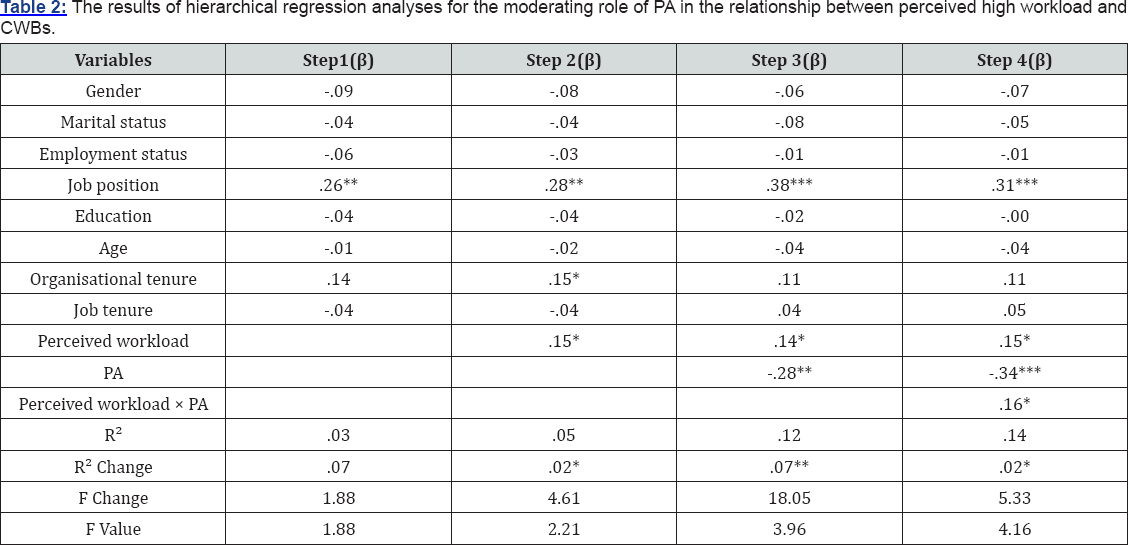

As shown in Table 2 above, the results of the hierarchical regression analyses indicated that the control variables tested accounted for 3.2 percent of the variance in CWBs. In the regression equation, only job position was significantly related to CWBs (β = .26, p <. 001).Perceived high workload accounted for 4.8 percent of the variance in CWBs far and above the control variables. In the regression equation, perceived high workload was significantly and positively related to CWBs (β = .15, p < .05). PA accounted for 12.1 percent of the variance in CWBs far and above the control variables and perceived high workload. In the regression equation, PA was significantly and negatively related to CWBs (β = -.28, p < .001). The results equally showed that there was a significant interaction effect between perceived high workload and PA and this interaction accounted for 13.9 percent of the variance in CWBs far and above the control variables, perceived high workload and PA. In the regression equation, the interaction effect was statistically significant (β = .16, p < .05).

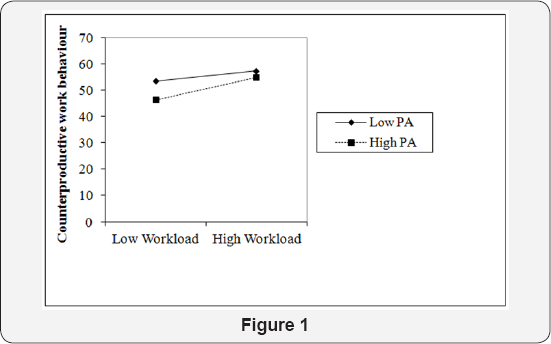

This finding showed that PA had a moderating effect in the positive relationship between perceived high workload and CWBs. The graphical representation of the significant interaction (see figure 1 below) was obtained by using the values of the predictor (perceived high workload) and moderator (PA) variables that were chosen one standard deviation above (high) and below (low) the mean [64]. As seen in Figure 1, individuals with high PA reported lower scores in CWBs despite perceiving high workload in their job.

Discussion

The present research investigated the relationship between perceived high workload, PA and CWBs. It mainly focused on PA as a moderator in this relationship. Consistent with assumption, perception of high workload had a direct and significant positive relationship with CWBs. This intuitive positive relation between perceived high workload and CWBs was expected and understandable. Several previous researches reported that pervasiveness of CWBs is largely due to strains that promote negative emotions such as anger, frustration, and depression [65]. This negative emotions experienced by individuals further create pressure for remedial action and engaging in CWBs is one of the ways some employees respond as a form of retaliation or attempt to bring the body back to equilibrium [66]. This result seems to be consistent with earlier studies which showed that high workload is acknowledged as an important predictor of burnout [46]. The result also seems to be in line with prior studies that prevalence of deviant workplace behavior was due to excessive workload [49,8,50]. This finding is also in line with Salami who found that job stress was positively related to CWBs [14].

The results of the current study also revealed that PA was significantly and negatively related to CWBs. This finding is in line with assumption that employees high in PA scores will report low scores on CWBs. The result follows the assertion that PA refers to the tendency to experience intense pleasant feelings. Employees high in PA are known for their enthusiasm and excitement making it difficult for such employees to engage in CWBs. More so, those who are high on PA experience positive emotions that involve high levels of activation or engagement [25]. Individuals high on PA have a more positive view of the world and engage more in positive work behaviors instead of CWBs [8]. This finding seems to be consistent with previous studies which found that PA has a negative relationship with CWBs. It also tends to support Colquitt et al. [59] who found that PA was negatively related to CWBs [15].

Furthermore, the results of the current study showed that PA moderated the positive relationship between perceived high workload and CWBs in such a way that employees with high scores on PA reported to engage less in CWBs despite having high perception of workload. This result is in line with the assertion that PA is a factor that increases an individual's adjustment, which is very significant in discussing the relationship between perception of high workload (a stressor) and CWBs. The reason for this result may also be founded on the grounds that PA as a component of the affective domain of subjective well-being, and also one of the indicators of happiness (subjective well-being) and psychological adjustment could absorb the pressure emitted by high workload and therefore suppress employee’s tendency to attack the organization or its members in the form of engaging in CWBs [55]. Similar findings have been reported in earlier studies which suggested that it is often pertinent to think that PA can reduce the effect of perceived organizational frustration (a negative emotion often engendered by work stressor) on CWBs [56].

Implications of the study

Since bank employees are the drivers of the business and are in constant contact with customers, managers must ensure that they equip their employees with accurate skills to perform their jobs and move the organisation forward. These skills will help in managing high workload and thereby reducing their tendency to engage in CWBs. Managers are encouraged to show good support to their employees. This is because when employees perceive that they are supported by their managers and colleagues such support can help employees to keep positive views about the working environment and this in turn can reduce their perception of workload. This is in line with Grandey's suggestion that support from work environment plays an important role in managing emotions and stress of service employees [67]. This support may be in the form of providing appropriate training programme on managing negative emotions to reduce their frustration, emotional exhaustion and instances of CWBs [68]. Also, managers of organization can grant job autonomy and therefore, emotional autonomy to employees [18]. Some studies have shown that job autonomy reduces stress due to emotion regulation process [66]. However, a social environment at work that is conducive can help employees identify themselves with the organization and its goals and this will lead to internalisation of organizational standards relating to healthy emotional displays [18].

Limitations of the study and suggestions for further studies

Like many other studies, this study is not without limitations. First, the sets of measure were distributed in 11 commercial banks in southeastern Nigeria. Though a reasonable number of respondents completed the measures, some declined from participating, this led to a relatively small sample size. Higher response rate from more employees could have made generalization more meaningful. Future researchers may include more constructs such as work-family conflict and recovery to be able to have a broader perspective of the process of employees resorting to CWBs. Given the nature of the data collected (crosssectional) the current study is short of establishing any causal effects. Hence, longitudinal data or experimental study is recommended to address such concern.

In this study, the responses to the measures were obtained from a single source and both the predictor and criterion variables are perceptual measures derived from the same respondents. This may result in common method variance. Common method variance is the "variance that is attributable to the measurement method rather than to the constructs the measures represent" [69]. Although given such situation, some researchers often point at social desirability bias as a weakness, and consent that results are more valid with multiple sources of data [18]. However, the results of a meta-analysis clear all of such doubts [35]. Berry and colleagues support the use of self-report for CWBs research as a viable alternative to other-reports. Besides, related patterns and magnitudes of relationships were found between a set of common correlates, such as job satisfaction and negative effect, and CWBs not considering whether CWBs was rated by others or by the self [70]. Therefore, social desirability does not seem to influence the results of CWBs.

Conclusion

The study was designed to address some key issues in organizational behavior - the moderating role of PA in the relationship between perceived workload and employee engagement in CWBs with bank employees as participants. The main finding showed that perceived high workload was significantly and positively related to CWBs. More so, PA was found to be significantly and negatively related to CWBs. More intriguing is the observed moderating role of PA in the positive relationship between perceived high workload and CWBs, in such a way that high PA weakened the positive relationship between perceived workload and CWBs. This implies that employees with high report of PA engage less in CWBs even when they perceive high workload.

References

- Davis Blake A, Pfeffer J (1989) Just a mirage: The search for dispositional effects in organizational research. Academy of Management Review 14: 385-400.

- Ashford BE, Humphrey RH (1995) Emotion in the workplace: A reappraisal. Human Relations 48(2): 97-125.

- House RJ, Shane SA, Herold DM (1996) Rumors of the death of dispositional research are vastly exaggerated. Academy of Management Review 21(1): 203-224.

- Shaw JD, Duffy MK, Ali Abdulla MH, Singh R (2000) The moderating role of positive affectivity: Empirical evidence from bank employees in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Management 26(1): 139-154.

- Spector PE, Fox S (2002) An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior: Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Human Resource Management Review 12(2): 269-292.

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E (2005) The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success?. Psychological Bulletin 131(6): 803-855.

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Personal Soc Psychol 54(6): 1063-1070.

- Miles DE, Borman WE, Spector PE, Fox S (2002) Building an integrative model of extra role work behaviors: A comparison of counterproductive work behavior with organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 10(1-2): 51-57.

- Larsen RJ, Ketelaar T (1991) Personality and susceptibility to positive and negative emotional states. J Personality Social Psychol 61(1): 132140.

- Douglas SC, Martinko MJ (2001) Exploring the role of individual differences in the prediction of workplace aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(4): 547-559.

- Fox S, Spector PE (2005) Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Fox S, Spector PE, Miles D (2001) Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior 59(3): 291-309.

- Penny LM, Spector PE (2005) Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of negative affectivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26(7): 777796.

- Salami SO (2010) Job stress and counterproductive work behavior: Negative affectivity as a moderator. The Social Sciences 5(6): 486-492.

- Dalal RS (2005) A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 90(6): 1241-1255.

- Lockyer TM (2013) Global cases on hospitality industry. Haworth Press, New York, USA.

- Lazarus L, Rodafinos A, Matsigos G, Stamatoulakis (2009) Perceived occupational stress, affective, and physical well-being among telecommunication employees in Greece. Social Science & Medicine 68(6): 1075-1081.

- Raman P, Sambasivan M, Kumar N (2016) Counterproductive work behavior among frontline government employees: Role of personality, emotional intelligence, affectivity, emotional labor, and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 32(1): 25-37

- Gilboa S, Shirom A, Fried Y, Cooper CL (2008) A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology 61(2): 227-271.

- Gilboa S, Shirom A, Fried, Cooper CL (2008) A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology 61(2): 227-271.

- Schaufeli WB, Enzmann D (1998) The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis 3: 8.

- Spector PE, Fox S (2005) The stressor-emotion model of counterproductive work behavior. In S Fox & PE Spector (Eds.), Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets pp. 151-174.

- Beehr T, Bhagat R (1985) Introduction to human stress and cognition in organizations. In T. Beehr & R. Bhagat (Eds.), Human stress and cognition in organizations: An international perspective, Wiley, New York, USA. pp. 3-19.

- Krischer MM, Penney LM, Hunter EM (2010) Can counterproductive work behaviors be productive? CWB as emotion-focused coping. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15 (2): 154-166.

- Cropanzano R, Weiss HM, Hale JMS, Reb J (2003) The structure of affect: Reconsidering the relationship between negative and positive affectivity. Journal of Management 29(6): 831-857.

- Shaw JD, Duffy MK, Jenkins GD, Gupta N (1999) Positive and negative effect, signal sensitivity, and pay satisfaction. Journal of Management 25: 189-205.

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Schilling, EA (1989) Effects of daily stress on mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57(5): 808-818.

- Schaubroeck K, Ganster DC, Kemmerer B (1996) Does trait affect promote job attitude stability? Journal of Organizational Behavior 17(2): 191-196.

- Cohen A (2016) Are they among us? A conceptual framework of the relationship between the dark triad personality and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). Human Resource Management Review 26(1): 69-85.

- O Boyle EH, Forsyth DR, O Boyle AS (2011) Bad apples or bad barrels: An examination of group-and organizational-level effects in the study of counterproductive work behavior. Group & Organization Management 36(1): 39-69.

- Spector PE, Fox S (2010) Theorizing about the deviant citizen: An attributional explanation of the interplay of organizational citizenship and counterproductive work behavior. Human Resource Management Review 20(2): 132-143.

- Spain SM, Harms P, LeBreton JM (2014) The dark side of personality at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35(S1): S41-S60.

- Bennett RJ, Robinson SL (2000) Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology 85(3): 349-360.

- Northwestern Life Insurance Company (1993) Fear and violence in the workplace. Minneapolis, MN: Author.

- Berry CM, Carpenter NC, Barratt CL (2012) Do other-reports of counterproductive work behavior provide an incremental contribution over self-reports? A meta-analytic comparison. Journal of Applied Psychology 97(3): 613-636.

- Bamfield J (2007) Global retail theft barometer. Nottingham: Centre for Retail Research.

- Chappell D, Di Martino V (2006) Violence at work (3rd edn,). Geneva: International Labor Office.

- Harris LC, Ogbonna E (2006) Service sabotage: A study of antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34(4): 543-558.

- Weiss HM, Cropanzano R (1996) Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior 18: 1-74.

- Lam W, Chen Z (2012) When I put on my service mask: Determinants and outcomes of emotional labor among hotel service providers according to affective event theory. International Journal of Hospitality Management 31(1): 3-11.

- Lazarus RS (1982) Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition. American Psychologist 37: 1019-1024.

- Bies RJ, Tripp TM, Kramer RM (1997) At the breaking point: Cognitive and social dynamics of revenge in organizations. In RA Giacalone, J Greenberg (Eds.), antisocial behavior in organizations Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, Califonia, USA.

- Lazarus RS (1995) Psychological stress in the workplace. In R Crandall, PL Perrewe (Eds.), Occupational stress, Taylor and Francis, Washington, USA.

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309-328.

- Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli, WB (2001) The job demands resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(3): 499-512.

- Mc Manus IC, Keeling A, Paice E (2004) Stress, burnout and doctors' attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning styles: A twelve-year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Medicine 2: 29.

- Khan FI, Rosman MD, Yusoff I, Khan A (2014) Job demands, burnout and resources in teaching a conceptual review. World Applied Sciences Journal 30(1): 20-28.

- Yorimitsu A, Houghton S, Taylor M (2014) Operating at the margins while seeking a space in the heart: The daily teaching reality of Japanese high school teachers experiencing workplace stress/anxiety. Asia Pacific Education Review 15(3): 443-457.

- Jonge JD, Peters MCW (2009) Convergence of self-reports and coworker reports of counterproductive work behavior: A cross-sectional multisource survey among health care workers. International Journal of Nursing Studies 46(5): 699-707.

- Bayram N, Gursakal N, Bilgel N (2009) Counterproductive work behavior among white-collar employees: A study from Turkey International Journal of Selection and Assessment 17: 180-188.

- Fredrickson BL, Levenson RW (1998) Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion 12: 191-220.

- Fredrickson BL, Mancuso RA, Branigan C, Tugade MM (2000) The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion 24(4): 237-258.

- Isen AM (2004) Some perspectives on positive feelings and emotions: Positive affect facilitates thinking and problem solving. In AR Manstead, N Frijda, A Fischer (Eds.), Feelings and emotions: The Amsterdam Symposium, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, UK. pp. 263-281.

- Fortunato VJ, Harsh J (2006) Stress and sleep quality: The moderating role of negative affectivity. Personality and Individual Differences 41: 825-836.

- Diener E, Suh E (1997) Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research 40(1-2): 189-216.

- Schiffrin HH, Nelson SK (2010) Stressed and happy? Investigating the relationship between happiness and perceived stress. Journal of Happiness Studies 11(1): 33-39.

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF (2004) Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality 72(6); 1161-1190.

- Prabha KS, Sandeep K (2016) Positive affectivity as a moderator of occupational stress and ill-health. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing 7(1): 41-44.

- Colquitt JA, Scott BA, Rodell JB, Long DM, Zapata CP, et al. (2013) Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology 98(2): 199-236.

- Hart SG, Staveland, LE (1988) Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. In PA Hancock N Meshkati (Eds.), Human mental workload). North-Holland: Elsevier Science Publisher’s pp. 139-183.

- Mason ES (1995) Gender differences in job satisfaction. Journal of Social Psychology 135(2): 143-151.

- Cohen J, Cohen P (1983) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, Erlbaum, New Jersey, USA.

- Darlington RB (1968) Multiple regression in psychological research and practice. Psychological Bulletin 69(3): 161-182.

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS (2003) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, Erlbaum, New Jersey, USA.

- Radzali FM, Ahmad A, Omar Z (2013) Workload, job stress, family-to- work conflict and deviant workplace behavior. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 3(12): 109-115.

- Hershcovis MS, Turner N, Barling J, Arnold KA, Dupre KE, et al. (2007) Predicting workplace aggression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 92(1): 228-238.

- Grandey A (2000) Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5(1): 95-110.

- Beigi M, Shirmohammadi M (2011) Effects of emotional intelligence training program on service quality of bank branches. Managing Service Quality 21(5): 552-567.

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SM, Lee J, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method variance in behavioral research: A critical review of theliterature and ecommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879-903.

- Reijseger G, Peeters MCW, Taris TW, Schaufeli WB (2016) From motivation to activation: Why engaged workers are better performers. Journal of Business and Psychology 32(2): 117-130.